|

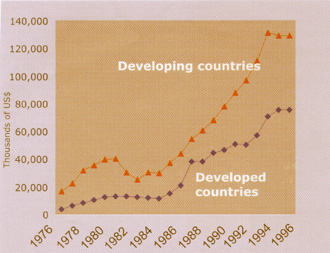

Figure 1. Export value of the

ornamental fish |

| Responsible Ornamental Fisheries Devin Bartley Fishery Resources Division

At the invitation of the organizers, |

The ornamental

fish sector is an extensive and global component of international trade, fisheries,

aquaculture and development. However, the scope of this sector and the impact on human and

aquatic communities are often unappreciated and often not accurately known. Global

statistics reported to FAO from Members indicate that the export value in 1996 of

ornamental fishes was US$206,603,000, while the import value was US$321,251,000. Since

1985 the value of the international trade in ornamental exports has increased at an

average growth rate of approximately 14 percent per year (Figure 1). Developing countries

account for about 63 percent of the export value. The value of the entire industry, when

non-exported product, wages, retail sales and associated materials are considered (Figure

2), has been estimated at US$15,000 million. Such a vast and important industry has the

potential to contribute to the sustainable development of aquatic resources, but may face

challenges due to increased attention to environmental and social issues. |

|

Figure 1. Export value of the

ornamental fish |

construction purposes (Ornamental Aquatic Trade Association

information). Improvement of fishery and trade statistics - It was

reported that approx. 8,000 species of marine fish are traded in the industry and most of

these are missing from FAO statistics; reporting to FAO is inconsistent due to different

countries evaluation of commodities; Destructive fishing practices - Some estimates indicate

that 20,000 fishers may be using sodium cyanide to capture coral reef fishes that destroys

coral reefs and other organisms, and results in eventual death of harvested fish. Aquaculture development - of the 8,000 marine species

traded, approximately 25 can be bred and cultured. There is a strong move to breed and

domesticate high value marine species and endangered species (Figure 4). However, |

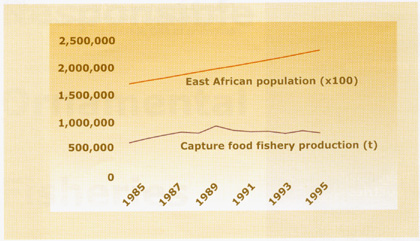

Figure 2. Ornamental fish, sold in plastic bags in Bangkok's "Chat o Chak" market, support activity in related articles such as fish food, aquarium supplies and plants. |

|

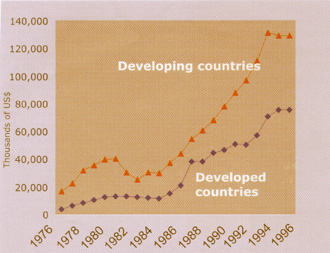

Figure 3. East Africa, example of an area, i.e. the Great Lakes of Africa, where capture of ornamental fish trade is practised in light of stagnating food fisheries and increased population growth. Capture food fishery production total from seven East African countries and their population total (FAO and UN Statistics).

|

farming runs of the risk of displacing small-scale Income generation - In areas

with little other options for environmentally sustainable development, some ornamental

fisheries are extremely lucrative, for example Dr Wijisekara stated that ornamental fish

account for 8 percent of the volume of exported fish from Sri Lanka, but this represents

70 percent of the value. Market access and availability will hinder development in remote

areas such as many Pacific Island States. Involvement of women - Some

culturing and tending of grow-out areas are predominately run by women such as in coral

culture in the Solomon Islands. Competition from other sectors

- Harvest of cardinal tetras in the Rio Negro, Brazil, is competing with a developing

sport fishery for large cichlids. As in other uses of freshwater, there are always moves

to divert water for agriculture without a full appreciation of the biological resources,

e.g. ornamental and food fishes, that are present in water bodies. Increased valuation of aquatic

resources - Organisms with no value as a food fish have often been destroyed or the

habitat that supports them has been degraded; however their value as an ornamental fish

provides motivation for fishery management and conservation as in the case of freshwater

stingrays from Amazonia. Certification and labelling -

In light of harmful fishing practices and the potential of overfishing, there is a

movement to certify ornamental fishes that are sustainably harvested. For the marine |

The purpose of FAO participation in the Conference was to acquaint the ornamental fish industry with international efforts that may impinge on them and to highlight the FAO Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries, as well as for FAO to learn more about this industry. There was strong support from those in attendance to have some involvement of FAO in helping the industry continue to develop responsible practices. |

Figure 4. Indonesian farm licensed to raise and sell the endangered ornamental Golden Dragon Fish, Scleropagus formosas (inset). Under CITES, each farm-raised fish must be tagged and the sale monitored to ensure wild stocks are not being traded. |

|

The ornamental fish industry and the people that rely on this for

livelihood can help ensure that international trade continues in a responsible manner and

that the international community does not overly restrict the industry, by becoming aware

of the issues and by following and promoting responsible practices that ensure

conservation and equitable benefit sharing. Actions toward this end would include, inter

alia: Eco-labelling to ensure

sustainable harvest or growing conditions and humane treatment of animals; Creation and adoption of

voluntary codes of conduct, such as those in the UK, and best practices such as are being

developed by Marine Aquarium Council; Avoidance of controversial

genetic technologies or the creation of novel life forms; Health certification for

transboundary movements of aquatic animals; Promotion of domesticated

ornamental fish where appropriate and the promotion of sustainable harvest of natural

populations where appropriate; Promotion of public zoos and

aquaria and other educational fora; |

The participants noted the lack of accurate information regarding:

and suggested that an improved information system and accurate reporting were crucial for the continued growth of the industry. In light of the above, FI may wish to examine more closely the ornamental fish industry with an initial focus toward improving the information base. FAO Fisheries and the Ornamental Aquatic Trade Association have often exchanged information and have enjoyed an informal, but productive, relationship in the past. |

|

Acknowledgements |