The study was recommended by the Asia-Pacific Forestry Commission

During the 17th session of the Asia-Pacific Forestry Commission (APFC), held in Yogyakarta, Indonesia in February 1998, the commission requested that FAO conduct a study on the efficacy of removing natural forests from timber production as a strategy for conserving forests. The Commission recognised that a number of countries in the Asia-Pacific region have imposed partial or total logging bans (or similar restrictions on timber harvesting) in response to rapid deforestation and degradation of natural forests. Several other countries in the region are also considering harvesting restrictions, along with other strategies, to promote forest conservation. The commission noted the importance of better understanding of the impacts and effectiveness of such bans. The various experiences of countries that have implemented such restrictions provide useful indicators of the efficacy of these measures, and suggested that an approach based on multi-country case studies would provide an effective means of analysis.

The principal objectives of the study were to:

investigate past and current experiences of Asia-Pacific countries in removing natural forests from timber production as a strategy for conserving forests;

assess the policy, economic, environmental, and social implications of logging bans and timber harvesting restrictions; and

identify conditions necessary for the successful implementation of logging bans or likely to enhance successful implementation.

In examining the history and experience of timber harvesting bans in natural forests, the study sought to understand the impacts on both conservation and production from the natural forests, including the implications and strategies for timber supply.

The study is mainly based on six country case studies

The study was carried out through six country case studies in New Zealand, People's Republic of China, Philippines, Sri Lanka, Thailand, and Viet Nam. The case studies were selected to represent examples of major efforts to apply logging bans comprehensively to natural forests outside established protected areas under diverse circumstances. In addition, situations where countries are considering further banning of harvest, or where bans have been recently announced but not yet fully implemented, were reviewed to gain further insights into background, policy issues, and implementation strategies.

A strong conservation ethic underlies logging bans in case study countries

Countries have different motivations for withdrawing forests from production. In each country in this study, there was a strong conservation ethic underlying decisions to withdraw forests from production, but the purposes and motives for wanting to conserve forests often differed markedly. While a number of commonalities can be observed among the countries reviewed, no two are exactly alike in costs borne, benefits accrued, culture, economic development, status and threats to forests, objectives or approaches used in removing natural forests from timber production.

In most countries reviewed, the 20 years preceding a decision to restrict or ban logging saw extensive deforestation and forest degradation. In several countries this drew forest stocks down to precariously low levels, but in others overall forest cover has remained satisfactory by international standards (Table 1).

| Country | Ban imposed (year) | Forest cover | % land area protected* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 (%) | 2000 (%) | Change in area, 1980–2000(%) | |||

| New Zealand | 1987 | 27.0 | 29.7 | 9.9 | 23.19 |

| P.R. China | 1998 | 13.5 | 17.5 | 30.1 | 6.05 |

| Philippines | 1991 | 38.4 | 19.4 | -49.5 | 2.02 |

| Sri Lanka | 1990 | 32.7 | 30.0 | -8.3 | 12.13 |

| Thailand | 1989 | 36.4 | 28.9 | -20.7 | 13.66 |

| Viet Nam | 1997 | 33.0 | 30.2 | -8.7 | 4.03 |

* World Conservation Monitoring Centre, 1996 (http://www.wcmc.org.uk/)

The case study countries have all undergone significant deforestation in their recent pasts…

In 1980, only China's forest cover was below the global average of 27 percent, and to some extent this is due to natural geographic factors. Nonetheless, all the countries have undergone significant deforestation in their recent past. For example, Viet Nam is reported to have had 14.3 million ha of forests in 1943, compared with 9.8 million ha in 2000. In China, the merchantable forest stock is estimated to have declined by 77 percent between 1950 and 1995,1 while New Zealand's forest cover declined from around 50 percent (pre-European colonization in 1840) to 27 percent today.

More recently, trends in forest cover have been more variable. Until the 1950s, forests were abundant in the Philippines and provided a major source of export revenue in the 1960s and 1970s. The Philippines' forests were largely converted to agricultural use in the late 1970s and 1980s. At its peak, deforestation was totalling more than 300 000 ha per annum. In 1991, the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) issued an administrative order, which banned timber harvests in all virgin forests as well as steep land and mountain forests. This slowed the rate of deforestation in the Philippines, although forest loss continued at a rapid pace after 1980 (Table 1) despite implementation of the logging restrictions. Policies allowed a continuation of harvesting in residual forests outside protected areas and watershed reservations, and areas below 1 000 m in altitude and with slopes less than 50 percent. Old-growth and valuable residual forests located in areas where Timber License Agreements (TLA) were cancelled or allowed to expire without renewal, have remained vulnerable to poachers, illegal cutters and slash-and-burn farming.

….Thailand, for example, has lost an annual average of 330 000 hectares of natural forests since 1960

Similar trends are evident in Thailand. During the last three decades, Thailand experienced ongoing deforestation, often at rates exceeding 3 percent per annum. Since 1960, Thailand has lost an annual average of around 330 000 ha of natural forest. Both Thailand and Philippines, had similar rates of deforestation throughout the 1980s, and both countries had reduced their forest covers to a similar percentage by 1990. Logging bans were implemented in both countries at about the same time. An important difference is that, in the post-ban period, deforestation has been significantly lower in Thailand than in the Philippines, despite continuing problems with encroachment and illegal logging in Thailand.

The New Zealand situation is markedly different from those of Thailand and the Philippines. Most forest clearing took place during the 19th century. The last 100 years have seen New Zealand develop a substantial plantation forest estate that complements an economy with a considerable agricultural emphasis. The country's low population in tandem with large surpluses of plantation-grown timber and agricultural products have removed most pressures on natural forests for supplying wood or agricultural land. Subsequently, New Zealand has chosen to heavily restrict logging in natural forests to help conserve these areas. The restrictions have not been driven by any acute sense of ecological crisis as in many other countries, but rather reflect widespread societal support for preserving remaining natural forests.

Forests in China are under much greater pressures than New Zealand's forests. A strong emphasis on reforestation in China during the past 25 years does, however, bear some similarity with forestry development in New Zealand. The establishment of around 34 million ha of plantations during the past 20 years gives China the world's largest plantation estate, and provides an opportunity for future large-scale substitution for wood from natural forests. In 1980, China's forest cover was 13.5 percent - the lowest of any of the case study countries. By 2000, however, forest cover had been increased to 17.5 percent - helping to enable the Government to implement a ban on logging of natural forests in the upper reaches of the Yangtze River and the middle and upper reaches of the Yellow River.

Plantation forests play a significant role in supplementing wood supplies

Plantation forests are also expected to play a supporting role in the implementation of a logging ban in Viet Nam. The net loss in forest cover in Viet Nam, since 1980, has been modest relative to the Philippines and Thailand. However, the net forest loss figures incorporate the establishment of more than 1 million ha of plantations. Between 1943 and 1995, 5.7 million ha of natural forests were cleared, an average of about 110 000 ha annually. Similar to China, there are heavy population pressures on Viet Nam's forests, and large areas of natural forest have been removed or heavily degraded. Only 5.5 percent of Viet Nam's remaining natural forests are considered “rich forests” (i.e. with over 120m3 per ha of growing stock). Another 16.8 percent are categorized as “medium-quality forests” (with between 80 and 120 m3 per ha of growing stock). The remaining natural forests are considered poorly stocked (less than 80 m3 per ha) or recently rehabilitated.

Non-forest sources of wood have become more important

The forestry situation in Sri Lanka reflects elements of the situations in all the other case study countries. Sri Lanka's closed canopy forest cover has dwindled rapidly from about 84 percent in 1881, to 44 percent in 1956 and subsequently to 27 percent in 1983. In common with the other Asian case study countries, the decline in forest cover is primarily due to rapid population growth, resulting land shortages and poverty. A ban on logging in all the natural forests was imposed in 1990. The logging ban, in association with other measures, has been relatively successful in curbing deforestation. At the same time, non-forest sources of wood have become more important. Homegardens, rubber and coconut plantations are estimated to have supplied over 70 percent of industrial roundwood in 1993. Only about 4 percent came from forest plantations. Forest plantations are expected, however, to play a more important role in supplying wood in the future.

Deforestation is the dominant issue motivating logging bans

The country case studies reveal a complex and variable mix of reasons for imposing logging bans and restrictions on harvesting in natural forests. The dominant issue is deforestation, with the primary objective of harvesting bans in most case study countries being to halt deforestation and degradation of natural forests. A choice to ban logging as a means of merely halting deforestation, however, reveals only an “option value” of forests. A more revealing question relates to the motivations behind choices to halt deforestation.

In spite of the crisis nature of political decisions to ban timber harvesting, desired conservation and protection policy goals are seldom clearly defined in operational terms. If a country and its people want more “conservation,” what is it they specifically want? What are the weaknesses of existing policies, management and outputs? What are the trade-offs among different uses and different forest values? How much will be given up to achieve conservation, and what are the costs? Difficult questions must be based on clear goals and objectives, and the evaluation of alternatives.

Popular support for conservation was an important factor in New Zealand

In New Zealand, it can be argued that decisions to restrict harvesting in natural forests attributed greater weight to pure environmental values of forests than in the other case study countries. Forest policy changes in New Zealand through the late 1970s and 1980s reflected the changing and turbulent political climate and popular support for forest conservation. By the time a number of multiple-use, sustainability, and other policies for state-owned natural forests gained official acceptance in the 1970s, public concerns about forest conservation had also gained momentum. Well-organized and informed environmental groups argued the case for forest conservation on ecological, aesthetic, and recreational-use grounds. In New Zealand, there was no overriding forestry crisis that motivated a ban; rather, the harvest restrictions reflected a public perception that the natural forests should be conserved.

The implementation of logging bans in the Philippines, Sri Lanka and Viet Nam recognise environmental values of forests, but also reflect more extreme situations in terms of rapid deforestation and forest degradation. In the Philippines, for example, a fear of losing the diverse dipterocarp forest altogether was raised as an argument for a logging ban in natural forests.

Extremely high rates of deforestation motivated the ban in the Philippines

More specifically, however, the Philippines' logging ban was implemented as a means of conserving biological diversity; to protect watersheds and safeguard coastal and marine resources; because of concerns over corruption and abuse of the TLA system; and as a means of slowing migration into forest areas and limiting the displacement of indigenous people.

| Motivation for restricting timber harvesting |

| There are a number of reasons for countries to restrict timber harvesting that are complementary or subsidiary to an overall objective of controlling deforestation. These include: |

|

Maintaining forest dependent livelihoods was a major concern in Viet Nam

In Sri Lanka, the harvesting ban similarly acknowledged that natural forests were heavily depleted and in need of protection to support their rehabilitation. At the same time, the ban was a response to concerns for safeguarding biodiversity, protecting soil and water resources, and preserving recreational, aesthetic and cultural values.

In Viet Nam, the area and quality of forests have declined unabated, directly threatening the lives of people in mountainous areas and causing an array of other impacts. The Government recognized a need for stronger measures to protect and develop the natural forests, stabilize forest ecosystems, and ensure sustainable development. The logging ban specifically aims to improve Viet Nam's wood production capacity by protecting and improving more than 9 million ha of existing forests. Supplementary policies aim to reforest an additional 5 million ha.

Natural disasters provided an initial catalyst for imposing logging bans

In several of the case study countries, natural disasters provided an initial catalyst for imposing logging bans. In Thailand, the logging ban was a direct response to devastating floods and landslides, which took the lives of 400 people in Nakorn Srithammarat Province in the southern part of the country in late 1988 (the logging ban was subsequently imposed in January 1989). Similarly, in China during 1998, flooding in the Yangtze River valley affected hundreds of millions of people and caused extensive damage to riverine areas amounting to a direct economic loss of 167 billion yuan.2 Following the floods, logging of natural forests was banned along stretches of the Yangtze and Yellow Rivers, and in several other critical provinces. In the Philippines, catastrophic flooding killed 7 000 people in Ormoc City, Leyte, in 1992. These floods were seen as a direct consequence of deforestation and reinforced commitment to maintain previously imposed logging bans. In each of these countries, while natural disasters provided catalysts for the bans, the objectives of timber harvesting restrictions extended far broader to encompass many of the objectives listed above.

Structures of bans and restrictions vary considerably across countries

Timber harvesting restrictions, and related implementation measures, vary considerably among the case study countries. While several countries, notably Thailand and Sri Lanka, have imposed blanket national bans on logging in natural forests, the supporting policy and regulatory measures in each country differ markedly. Other case study countries have imposed only partial logging bans, covering certain types of natural forests or specific geographic areas (as in China) or a combination of both (Philippines and Viet Nam).

Thailand has implemented a complete ban on logging in natural forests. This was achieved by cancelling all natural forest logging contracts and concessions, and ceasing to issue approvals for new concessions. Logging is still allowed in plantation forests, and the development of large-scale commercial plantations is being actively promoted through the Forest Plantation Act 1992. Illegal logging in natural forests has remained widespread in Thailand, while significant areas of forest are still cleared for shifting cultivation or conversion to permanent agriculture. Consequently, Thailand has continued to experience net deforestation subsequent to the ban, but at lower rates than previously.

2 US$1 = 8.27 yuan (January 2001).

Total bans on logging have been imposed in natural forests of Thailand and Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka also maintains a total ban on logging in natural forests. The Sri Lankan logging ban arose from extensive deforestation in the 1970s and 1980s, exacerbated by inappropriate policies that emphasized the use of natural forests for timber production while paying little attention to forest conservation. Assessments reveal that commercial and political pressures had determined logging practices in Sri Lanka, resulting in severe degradation and depletion of the growing stock in many areas. In 1988, selective felling in the dry zone forests was suspended pending the compilation of forest inventories and forest management plans. This suspension became a complete ban in 1990 at the time of the overall ban on logging in all natural forests. The principal thrusts of forest policies supporting the ban are encapsulated in Sri Lanka's National Forest Policy, adopted in 1995. The Policy has forest conservation as its primary emphasis, and stipulates that a large proportion of the country's forests be completely protected. It also advocates widespread implementation of collaborative forest management.

A partial ban in the Philippines applies mainly to old-growth and steep land forests

Logging bans that apply nationwide in the Philippines are partial bans, in that they affect only timber harvesting in old growth forests, and to forests on steep slopes, areas located more than 1 000 m above sea level, and areas covered by the National Integrated Protected Areas System (NIPAS). Additionally, however, there are total bans on all timber harvesting in natural forests in many provinces of the country. A central aspect of forest policy accompanying the bans is the widespread implementation of communitybased forest management (CBFM). This paradigm shift recognizes that forest management can only succeed if communities actively participate in planning and decision-making. Despite shifts in management orientation and the various logging bans, the Philippines has been less successful in halting deforestation than most other countries. In part, this is due to the continuation of logging in some areas of the country, but more importantly to an inability to adequately control extensive slash-and-burn farming and agricultural expansion in logged-over areas and brushlands. Clearly, if the primary cause of deforestation and forest degradation is agriculture, rather than industrial forestry, a logging ban can be of only limited use in controlling degradation.

China's ban is region-based

China's logging bans apply only to natural forests in specified regions. The bans, imposed in 1998, cover natural forests in the upper reaches of the Yangtze River, the middle and upper reaches of the Yellow River and the upper reaches of the Songhuajiang River, Sichuan, Yunnan, Chongqing, Gansu, Shaanxi and Qinghai Provinces. The logging bans constitute an integral part of the new Natural Forest Conservation Program (NFCP). The specific objectives of the NFCP are to reduce timber harvest volumes from natural forests from 32 million m3 (in 1997) to only 12 million m3 by 2003; conserve 41.8 million ha of natural forests in the upper reaches of the Yangtze River, upper and middle reaches of the Yellow River, and in Inner Mongolia, Northeast China, Xinjiang Ugur Autonomous Region and Hainan Province; and establish 21.3 million ha of timber plantations from 2000 to 2005 in the upper reaches of the Yangtze River and the upper and middle reaches of the Yellow River.

Viet Nam's ban covers a mix of designated forest types and regions

Logging bans in Viet Nam cover some specific categories of forests, as well as all natural forests in some regions. The current bans are an accumulation of transitional bans, which began in 1992 when logging in watershed protection and special-use forests was banned, and forest exploitation in seven provinces in the north was also halted. Five years later, the Government imposed a logging ban to further strengthen forest protection and reforestation of barren hills. A permanent logging ban was imposed in special-use forests, and a 30-year logging ban was instituted in critical watersheds. All commercial logging was prohibited in remaining natural forests in the northern highlands and midlands, the southeast, and in the Mekong River and Red River Delta Provinces. Logging bans presently cover 4.8 million ha of forestlands, accounting for 58 percent of the country's natural forests. Viet Nam's national land-use plan envisages extensive reforestation and regeneration efforts. These include targets to reforest (through planting and natural regeneration) more than 5 million ha of bare lands and highly degraded forestlands by 2010.

| Measures assisting the implementation of China's logging bans |

| A range of measures that support effective implementation of China's logging bans are being instituted. They include: |

|

Restrictions in New Zealand are based on sustainability criteria and large-scale transfers to the conservation estate

In New Zealand, the ban is largely de facto, in that it is based around an extensive transfer of natural forests to the protected area network, allied with stringent restrictions relating to sustainable harvesting in other natural forests. The sequence of logging restrictions has its roots in the early 1970s, when heightened public concern over forest conservation led to a gradual shift in forest policy goals. For natural forests, these largely culminated in a restructuring of Government forest administration, which saw management responsibilities for most of New Zealand's State-owned natural forests pass from the Forest Service to the Department of Conservation. This process hastened protected-area status to most of the State-owned natural forests. Natural forests that remained outside the protected area network were subject to rigorous sustainability criteria, which largely restricted harvesting.

The New Zealand case study illustrates the benefits of a gradual policy transition whereby over a considerable period of time alternative timber supplies (plantations, in the case of New Zealand) were established in anticipation of a decline in natural forest production. While the official removal of natural forests from harvesting was somewhat abrupt under national policy shifts in New Zealand, the transition had essentially been accomplished over prior decades. The establishment of a separate national Department of Conservation, with distinct goals, funding and human resources assured follow-up management and planning targeting the conservation objectives. It was perhaps incidental that the Government also chose to privatize State-owned plantations and withdraw from commercial timber production.

| Provisions of New Zealand's Forests Act designed to protect indigenous forests |

| New Zealand's Forest Act of 1949 was amended in 1993 to include stringent restrictions on harvesting in natural forests. The new indigenous forest provisions apply to about 1.3 million ha of private natural forests and about 12 000 ha of State lands that remain available for timber production. The Act also included export restrictions for wood products from natural forests, which largely replaced a previous export ban imposed in 1990. |

| The new provisions required mills to register with the Government and imposed restrictions on milling and exports. A transitional four-year period of harvesting (from 1992 to 1996) was also provided for, based on the mills' pre-legislation cutting levels. The intention was to allow the industry to adjust more smoothly to the change in supply. The amendments still offered limited opportunities for landowners to benefit from natural forest timber production and provided for a continuing role for specialist timber species. However, they also imposed specific restrictions, including explicit prescriptions to cover the management of natural forest species. The amended Act also required the preparation and approval of sustainable forest management plans consistent with specified management prescriptions. |

Logging bans imply a trade-off between economic and environmental aspirations

A decision to impose logging restrictions involves clear trade-offs between economic and environmental benefits. Impacts on the social dimensions of forestry are likely to be mixed. On the one hand, employment and incomes are likely to be seriously affected. On the other, improved environmental quality is likely to accrue benefits relating to health, aesthetics and recreation. Consequently, the relative success of logging bans, depends on the extent to which environmental and social benefits exceed economic and social costs.

While the case studies reveal that some forest conservation objectives have been achieved, failures in providing effective forest protection and lack of progress towards halting deforestation appear to be more common results. The adverse economic and social impacts can be measurably discerned, undermining the incentives for sustainable management, conservation and protection of non-timber values. Removal of natural forests from timber production has had significant impacts on the forest products sectors (production, trade and consumption) in several countries and important and sometimes disruptive effects on neighboring countries through both legal and illegal trade, timber smuggling, and market disruptions.

The following sections discuss the effects of the various logging restrictions according to key indicators such as:

Timber production

Alternative sources of wood

Patterns of international trade

Socio-economic impacts

Competitive and comparative advantages

Achieving conservation objectives

Logging bans generally imply a decline in wood production…

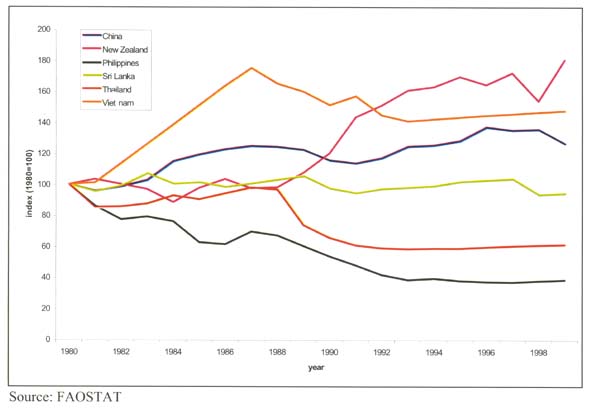

The most immediate impact of logging restrictions would expectedly be a decline in the production of industrial roundwood. Depending on the extent of restrictions, the availability of alternative wood supplies, and the extent to which the restrictions are effectively enforced, significant declines in wood production may be observed. Figure 1 shows indices of industrial roundwood production since 1980 in the six countries reviewed in the case studies.

Several discernable trends are evident in Figure 1. In Viet Nam, for example, the most significant trend is a very rapid acceleration in industrial roundwood production through to 1987. In real terms, production in 1987 peaked at 5.4 million m3. A 1992 ban on the export of roundwood, sawnwood and rough-sawn flooring planks is reflected in a modest decline in timber production. The impacts of the 1997 logging ban are less clear (Figure 1). Nonetheless, planned wood production in Viet Nam is expected to decline to 2 million m3 (an index value of 65), with 85 percent of production to be harvested from plantation forests.

Figure 1: Indices of industrial roundwood production in case study countries (1980–1999)

…but, this is dependent on the availability of alternative wood sources…

The impacts of logging bans on wood production are most obvious for Thailand and the Philippines. In both countries, the imposition of logging bans in the late 1980s resulted in marked declines in timber production. In Thailand, the implementation of the full natural forest logging ban in 1989, saw annual wood production decline from 4.6 million to 3.5 million m3 in the span of one year. By the mid-1990s, wood production had reached a plateau of around 2.8 million m3. Thailand's natural forest harvest has declined from about 2 million m3 prior to the logging ban, to about 55 000 m3 (recorded harvest) in 1998.

In the Philippines, the logging bans accelerated a downward trend in timber production. Timber production in the Philippines reached a peak of around 12 million m3 per annum in the early-1970s. By 1990, production had declined to 5 million m3, and to around 3.5 million m3 by 1998.

In Sri Lanka, the logging ban imposed in 1990 has had little evident impact on wood production. This is mainly a result of a substantial shift to alternative wood supplies. Harvests from State-administered natural forests fell from 425 000 m3 in 1990 to nearly zero, creating an almost total dependence on supplies from homegardens, rubber and coconut plantations and forest plantations.

…for example, New Zealand's plantation forests

In New Zealand, this substitution has been even more marked. Since the 1920s, New Zealand had been establishing an extensive plantation forest estate as an alternative to natural forest timber supplies. When large tracts of natural forests were transferred to the conservation estate, or otherwise subjected to logging restrictions, the country was already harvesting the vast majority of its wood from plantation forests. The natural forest harvest experienced a further decline in production of around 200 000 m3 in 1987. At the same time, the country's plantation forest harvest exceeded 9 million m3 in 1987, and grew to more than 18 million m3 by 2000. Less than 1 percent of New Zealand's annual wood production is currently harvested from natural forests.

Wood production in China, Philippines, Thailand and Viet Nam has declined since the advent of bans

The impacts of China's logging ban on domestic timber production are less evident. Industrial roundwood production grew steadily throughout most of the 1980s and 1990s. Despite this growth, prior to the imposition of the logging ban, Chinese wood supply projections estimated a deficit in supply for 2003 of 7.6 million m3. The logging ban has an ambitious goal of reducing harvests in State forests from the 1997 level of 32 million m3 to a planned level of 12 million m3 by 2003. The logging restrictions are, consequently, likely to exacerbate the estimated deficit to over 27.5 million m3.

For China, Philippines, Sri Lanka, Thailand and Viet Nam, the aggregate annual reduction in timber production following the implementation of comprehensive logging bans is estimated at 29.5 million m3.

The imposition of logging bans in natural forests involves significant assumptions about countries' abilities to access wood and fibre from other sources of supply. In general, primary alternative sources are:

Natural forests not covered by bans

Forest plantations

Other non-timber plantations (e.g. rubberwood and coconut)

Trees outside forests

Imports

Each of the case study countries has planned or employed significantly different strategies for accessing alternative wood supplies.

In New Zealand, plantations have steadily replaced the natural forests as the mainstay of wood processing industries since the 1950s. The industry has emphasized the utilization of increasing volumes of relatively fast-growing radiata pine. In 2000, 18 million m3 of roundwood (over 99 percent of the total) was harvested from forest plantations and less than 100 000 m3 came from natural forests. Much of the radiata pine is in the “post-tending” age class (10 to 25 years). Maturing stands mean that the total production is likely to double within the next 10 years. New Zealand is currently producing large surpluses of wood beyond domestic requirements and is consequently in a very favorable position relative to the other case study countries.

Plantations will be important sources of wood supply in China, Viet Nam, and New Zealand

Plantation forests are also at the heart of wood supply planning in Viet Nam and China. Viet Nam is at an early stage of further restricting timber harvests in the natural forests. Success of this effort will be largely determined by the implementation of the country's Five Million Hectare Reforestation Program, which is intended to gradually shift timber harvesting from natural forests to newly established plantations. This program envisages that plantations will provide up to 17.5 million m3 of wood for domestic industrial consumption by 2010, with an additional 10 million m3 for use as fuelwood. The ability of Viet Nam to adequately meet future demand, particularly after 2005, depends critically on the successful implementation of this program.

China's plantation programme is the world's largest…

China has faced a growing “supply-demand gap” in timber as the quality of natural forests has continued to deteriorate, while most plantations remain several years from maturity. China has ongoing programs to expand plantations for timber production and ecological protection. For example, China presently has about 34 million ha of plantations, including “timber” plantations of almost 12 million ha. The NFPC anticipates the establishment of a further 21 million ha of timber plantations in the upper reaches of the Yangtze River and the upper and middle reaches of the Yellow River between 2000 and 2005.

Timber plantations as an alternative source of supply in China

The Chinese Government plans to gradually shift timber production from natural forests to plantations. The output from plantations is still well below expectations and requirements, however. Plantations are expected to supply 13.5 million m3 in 2000 and 39.3 million m3 by 2005. Chinese fir, Masson's pine, larch, Chinese pine and cypress account for 88.5 percent of coniferous plantations. Poplar, eucalyptus, soft broadleafs, hard broadleafs and mixed broadleafs account for 92.8 percent of broadleaf plantation species. Based on these projections, it may be possible for plantations to become the main source of industrial timber in China, provided plantation management practices are improved and the plantation areas and species structure are adapted to market demands.

| Species | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2005 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese fir | 2 780 | 2 780 | 5 280 | 5 280 | 17 850 |

| Masson's pine | 39 | 39 | 39 | 390 | 2 290 |

| Larch | 83 | 83 | 83 | 83 | 83 |

| Chinese pine | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 60 |

| Cypress | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 37 |

| Others | 263 | 263 | 263 | 263 | 1 580 |

| All Conifers | 3 165 | 3 165 | 5 665 | 5 665 | 21 900 |

| Poplar | 1 750 | 5 760 | 5 760 | 5 760 | 14 580 |

| Eucalyptus | 110 | 110 | 110 | 1290 | 1990 |

| Soft broadleaf | 490 | 490 | 490 | 490 | 620 |

| Hard broadleaf | 32 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 32 |

| Mixed broadleaf | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 120 |

| Others | 150 | 150 | 150 | 150 | 100 |

| All Broadleaf | 2 592 | 6 602 | 6 602 | 7 782 | 17 442 |

| Total | 5 757 | 9 767 | 12 267 | 13 447 | 39 342 |

…but, plantations in Thailand and the Philippines have not developed as planned

The wood supply situations in Thailand and the Philippines illustrate economic downsides that may arise if assumed commercial plantations do not develop as planned. In Thailand, for example, the Reforestation Campaign of 1994–1996 specified a goal of establishing some 800 000 ha of plantations to offset the effects of the logging ban. New commercial plantation establishment has fallen far short of this goal, however, totalling only 164 000 ha by 1999. Large-scale industrial plantations have been opposed by rural communities. Efforts to promote small-scale plantations had limited success. Lack of access to forestlands, weak incentives and tenure arrangements, and limited capital for investment have all constrained plantation development. At present, it is clear that plantation establishment has not met expectations, nor are plantations supplying a significant volume of industrial timber.

Plantations provide only a minor source of wood supplies in the Philippines

The wood supply situation in the Philippines is similar. Plantation establishment was expected to increase markedly, and plantation wood supplies were expected to contribute significantly as a substitute for natural timber supplies. Projections made in 1990 forecast plantation production in 2000 would total 2.8 million m3. At present, however, only a limited area of the plantations is available for harvest, with 1998 production totalling only 45 000 m3. The most recent estimates forecast annual plantation yields of only 300 000 m3 during the next decade. At present, concession logging in secondary natural forests, coconut plantations, imports and “unaccounted sources” all constitute more important supply conduits than plantations (Table 3).

| Source | Estimated volume (thousand m3) | Percent of total |

|---|---|---|

| Annual allowable cut from | 588 | 12 |

| natural forests (residual) | ||

| Forest plantations | 45 | 1 |

| Imports | 796 | 16 |

| Coconut lumber | 721 | 14 |

| Other (illegal cuts and other | 2 850 | 57 |

| substitutes) | ||

| Total | 5 000 | 100 |

Trees outside forests are the most important wood source in Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka demonstrates the potential to restrict harvests in natural forests by shifting to alternative timber supplies. The reduction in natural forest wood supplies arising from the logging ban has been compensated mainly by increased harvests from homegardens and other non-forest wood sources, which doubled production between 1988 and 1993. Homegardens accounted for 40 percent of total wood production by 1996, while rubber and coconut plantations provided 15 percent of wood supplies and forest plantations provided 5 to 6 percent.

Imports are a significant source of wood in several countries

The Asia-Pacific region has long engaged in international trade of timber and wood products. In 1980, the region imported more than 70 million m3 roundwood equivalent of timber while exporting 44 million m3. Importing wood is, consequently, a ready means of meeting shortfalls in domestic production. Several of the case study countries have turned to imports as a means of supplementing wood supplies constrained by logging bans and restrictions. Most notably, Thailand, the Philippines and Viet Nam have increased imports to offset timber shortages. China has also identified the need for greater imports, at least during the transitional period leading toward greater production capacity of plantations.

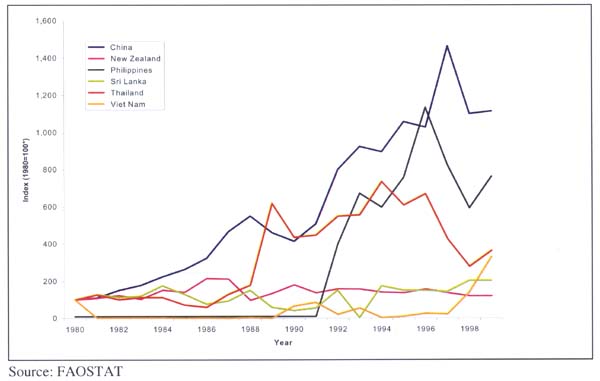

There has been little discernable change in import volumes into Sri Lanka and New Zealand in response to changes in harvesting regulations (Figure 2).

Changes in import volumes depend on availability of alternative supplies

Increases in sawntimber imports as a result of the implementation of logging bans are, however, clearly evident in the Philippines. Thailand and Viet Nam. In the Philippines, sawntimber imports prior to 1992 were virtually non-existent. Following the implementation of various logging bans, however, imports of sawntimber skyrocketed to more than a 0.5 million m3 in 1996. Similarly in Viet Nam, imports of sawntimber between 1981 and 1997 averaged only 5000 m3 per annum. The implementation of the logging ban coincided with sawntimber imports accelerating to 100 000 m3 in 1999. In Thailand, the logging ban resulted in sawntimber imports increasing from 447 000 m3 in 1987 to 2.1 million m3 in 1989. Similar import trends occur across a range of other forest products.

Figure 2: Indices3 of sawntimber imports in case study countries (1980–1999)

Import policies may shift environmental degradation elsewhere

International trade also opens the possibility of shifting environmental damage and deforestation to other countries or regions. One country taking actions to protect and conserve its natural forest resources can easily “export” harvesting problems to another supplier country. For example, Thailand's logging ban has fuelled both illegal logging and greater imports along the border areas of Laos, Cambodia and Myanmar. Protection of natural forests in China has led to greater imports from the Russian Federation, Myanmar and developing countries further afield. These increases in imports may be contributing to unsustainable harvesting in some of these places. Viet Nam also imports timber from Cambodia and Laos, allegedly in part from illegal harvests. While difficult to document, these effects raise important issues regarding the environmental and protection policies of exporting countries.

3 To assist scaling, the index value for the Philippines in 1980=10.

A range of qualitative socio-economic impacts of logging bans can be identified

Logging bans imposed in the Asia-Pacific region under conditions of crisis or as emergency responses to major natural disasters have seldom included supplementary strategies to effectively manage the withdrawn forests to achieve the desired environmental and protection goals. The typical response has been to focus on the immediate tasks of enforcing the logging bans or harvest restrictions.

When social, economic and environmental impacts are not identified, and mitigative strategies developed, the policy changes may have unexpected and unintended impacts. Government revenues decrease due to lower harvests, declining royalties and reduction of tax revenues. Government expenditures may increase due to necessary investments in reforestation activities, institutional restructuring, training of personnel and implementation of new management schemes. Previously employed workers may need retraining, and income supplements in the short run. Profitability of operations may decline, discouraging individual, household and private sector investments.

Logging bans may alter national comparative advantages in forestry

Comparative advantage is an elusive concept, largely based on market economics, prices and costs, and relative resource endowments. In broad terms, comparative advantage is held by a country that can produce a particular good more efficiently relative to other production opportunities in that country or other countries. In the context of logging bans, comparative advantage is crucial in determining patterns of change in wood production. The implementation of logging restrictions may shift comparative advantage to other areas within a country, or even between countries. For example, a country that has enjoyed a comparative advantage in harvesting natural forest timber may not enjoy a similar advantage in the production of alternatives such as plantation-grown timber. Thus, a change emphasising production in small-scale, community-based or individual household plantations may ultimately prove uneconomic in comparison to imports.

New Zealand and Sri Lanka retain comparative advantage

New Zealand provides a good example of comparative advantage in commercial plantations. The ready availability of land for afforestation, technical development of fast-growing radiata pine, market development efforts, efficient infrastructure, and a strong private industry willing to invest in plantations have combined to create a comparative advantage for plantation forestry. New Zealand has an increasingly large capacity to export plantation timber throughout the Asia-Pacific region, often more economically than other countries' ability to grow timber for themselves.

Comparative advantage shifts between regions in China

Sri Lanka also demonstrates the possibility of restricting harvests in natural forests by shifting output to economically viable alternative timber supplies derived from non-forest homegardens, plantations, and imports. The availability of suitable land, and incentives for non-State plantations and growing of timber have been instrumental in offsetting the reduction in natural forest timber production.

For China, a switch to predominantly plantation-based timber supplies will have substantial impacts intraregionally. Logging bans in China will pose a serious threat to established forest-based enterprises in the traditional state-owned natural forest regions of the Northeast, Inner Mongolia and Southwest China. Plantations will result in new production capacity in the southern coastal provinces, which possess favourable conditions for growing high-yield, fast-growing species and are located close to major markets.

Thailand and the Philippines lose comparative advantage?

While biophysical conditions for growing trees are favorable in Thailand and the Philippines, institutional, policy and investment infrastructures in both countries have not effectively supported commercial plantation development. As a consequence, both Thailand and the Philippines have become major net importers of timber since imposing harvesting restrictions on natural forests. This failure to attract investments in plantations indicates that comparative advantage for increasing timber supplies may reside with countries that already have viable, maturing intensively managed plantations or those still allowing the export of timber from natural forests (for example, the Russian Far East).

Viet Nam, which has staked the success of its efforts to protect natural forests on the development of new plantation resources under the country's Five Million Hectare Reforestation Program, has yet to demonstrate the comparative advantage of this approach. To date, many technical, social and economic issues remain unresolved.

Considerable discussion has focused on the relative success of countries in adjusting wood supply strategies to the withdrawal of natural forests from wood production. The corollary of this issue relates to the success of strategies of withdrawing natural forests from production in terms of meeting conservation objectives.

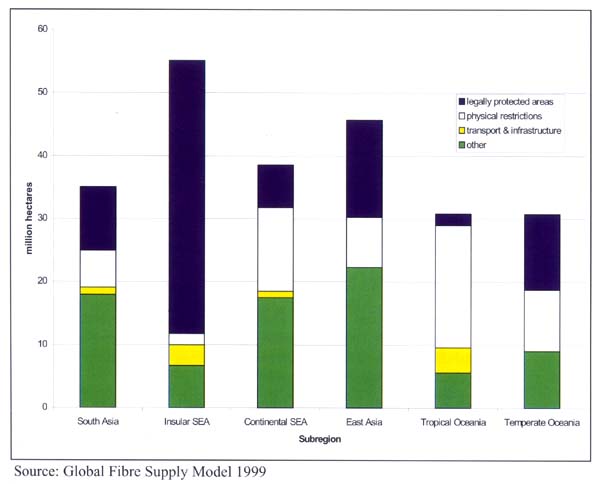

Large areas of forest in the AsiaPacific region are unavailable for harvesting

Substantial forest areas in the Asia-Pacific region are presently unavailable for harvesting for a variety of reasons. The FAO Global Fibre Supply Model4 estimates that, in the Asia-Pacific region, a total of 90 million ha of forests are in legally designated protected areas (IUCN forest management categories I–II). A further 147 million ha are considered to be “unavailable for harvesting” due to physical or economic constraints, though these areas are not formally designated for conservation. These constraints include physical terrain which makes harvesting financially unprofitable using existing technologies and at current prices (58 million ha), forests where transport cost or lack of infrastructure precludes harvesting (10 million ha), or where forests are insufficient (due to degradation or an absence of commercially valuable species) to warrant harvesting (79 million ha). Figure 3 categorizes the distribution of these forests by subregion.

4 FAO 1999: The Global Fibre Supply Model

Figure 3: Asia-Pacific natural forests unavailable for harvesting due to legal, technical and economic constraints

In many countries where extensive areas of forests have been legally designated as protected areas, considerable concerns remain over the adequacy of protected area management. A simple change in legal status from “available for harvesting” to “unavailable” or “legally protected” does not in itself assure either protection or conservation. Much of the legally protected natural forest in Asia and the Pacific is at risk of further deforestation or degradation due to ineffective policies for protection, inadequate resources for management planning and implementation, presence of forest-dependent people, and other constraints.

Logging bans create de-facto conservation areas

The country case studies indicate that substantial areas of natural forests have been legally protected or de-facto protected through blanket logging bans. Around 64 million ha of forests in the case study countries have, as a result of logging bans, become subject to protection. The recent implementation of the NFCP in China will initially encompass some 42 million ha of natural forests most critically in need of protection and rehabilitation. About 5 million ha of natural forests in each of New Zealand and the Philippines were brought into protected status - under separate legal administration as conservation forests in New Zealand but as de-facto conservation areas in the Philippines. About 8 million ha in Thailand have been closed to logging and are either declared protected areas or are awaiting formal designation. Sri Lanka increased legally protected natural forests by about one million ha under the logging ban, placing these forests under separate administration. Viet Nam has added some 4 million ha to its protected areas as a result of its logging bans. An important point is that where logging bans create de facto protection from industrial forestry, this protection does not necessarily extend across other activities such as agriculture. Thus, in countries such as the Philippines, where agriculture remains a significant contributor to forest degradation, logging bans are likely to be less effective.

Difficult to measure conservation “success”

Measures of conservation achievement attributable to logging bans or restrictions are largely lacking. Success is usually expressed in terms of area administratively or legally closed to logging. The extent to which protection of these areas will be effective in the long run remains unclear. Conservation and protection require much more than the simple elimination or reduction of timber harvesting. Protection is most successful where strong supportive policies and institutional capacity exist (or are created) to effectively carry out the desired conservation mandate. In New Zealand, for example, natural forests have been placed under the separate administration of a Department of Conservation with supporting policies, operational support and professional staffing. Even there, however, the elaboration of specific conservation and protection goals is still somewhat indirect, leading to difficulties in monitoring and measuring conservation success in either quantitative or qualitative terms.

Questions as to how well bans are being enforced

In the other case study countries (China, Thailand, Philippines, Viet Nam) the separation of functions is not fully defined in organizational structures or practical operational management. This potentially creates confusion or conflicts within forestry and natural resources units. Often the “timber culture” of traditional foresters casts doubts about the commitment to protection and conservation, especially where professional staffing is limited or inadequate. Similarly, ineffective enforcement of bans, the failure to provide adequate resources for management and the failure to facilitate innovative participatory management in support of conservation and protection of closed areas make the realization of intended goals improbable. For example, experiences in many parts of Thailand and the Philippines show that lack of community participation in conservation and protection discourages consensus and support, and frequently leads to local resistance to forest management activities.

Effective policy decisions require that the purposes of bans be clearly defined

Terms such as conservation, protection, biodiversity, and environmental values invoke broad support but do not directly convey or identify the expected results or practical outcomes from policy changes, including logging bans. Images vary widely from simply practicing good forest management to absolute preservation of natural forest ecosystems. Thus, invoking a logging ban merely as a means of achieving forest conservation fails to specify a sufficiently clear objective and may consequently hinder the identification of effective and efficient policy choices. Without knowing what new outcomes are desired, and at what cost and level of achievement, it is difficult to assess effectiveness of actions. For example, a goal of reducing deforestation is substantively different from a goal of protecting habitat for endangered species of wildlife, or protecting biodiversity. Policy instruments appropriate for one of these possible goals may be ineffective or counter-productive for the others.

A failure to adequately regulate timber harvesting and to assure either sustainable forest management or environmental protection is a primary cause of calls for timber harvest bans. In the absence of more specific goals, however, the operational objective of logging bans is often that of halting logging rather than creating and implementing new and innovative forms of conservation management. Thus, as a policy instrument, the banning of timber harvesting may well provide only a first step in ameliorating the present symptoms of forest management failures. A fuller consideration of alternative policy instruments may provide more efficient and effective solutions.

A common assumption is that halting logging is an effective means of minimizing the negative consequences of inappropriate forest use and poor forest management. The country case studies illustrate that this is true only in part. A logging ban is only one of a number of possible strategies. Other strategies and solutions have seldom been evaluated for possible feasibility and efficacy.

Bans are the most stringent of policy tools to control logging

In some instances, forests may need to be permanently closed to timber harvesting if such activity is deemed incompatible with preferred uses. In such cases, logging bans clearly constitute a central component of a desirable strategy. In many instances, a less stringent means of regulation could be implemented to address problems such as socio-economic pressures, lack of resources for monitoring and enforcement, or corruption. Forests could continue to be harvested, but perhaps under modified management techniques such as reduced impact logging (RIL). More effective guidelines for forest practices (e.g., codes of practice), and active monitoring of logging could assure compliance with established forestry regulations, use rights and sustainable harvest levels, and minimize illegal harvesting and encroachment on forests.

Still other situations may require only temporary or partial closure to allow for forest rehabilitation. Such bans may buy time to assess long-term goals and objectives, develop appropriate criteria, and implement management plans. Temporary or short-term logging bans (“time-out” strategies) also allow degraded forests a respite from further damage.