Along rivers and mountain streams, wherever water can be diverted onto land neither needed nor suitable for arable crops, a hay crop is taken, either from natural herbage or from sown lucerne. In some places, sainfoin (Onobrychis viciifolia) is grown on drier cultivated land. Lighter hay crops may be taken from dry hill slopes not required for grazing. The wild hay meadows vary considerably in quality: some are rich in natural legumes and forage grasses; others are in poor condition, especially where poor drainage and over-watering have lead to incursion of sedge (Carex spp.) rushes (Juncus spp.), reeds (Phragmites spp.) or mare's tail (Equisetum spp.). Heavy grazing in early spring has a detrimental effect on hay meadows, as does heavy stocking on lucerne and sainfoin aftermaths after the last cut of hay in autumn.

Lucerne and sainfoin have been grown in this part of Turkey for centuries - possibly even millennia. The indigenous ecotypes still widely used are generally long-lived; ten- to fifteen-year stands are common; stands of over twenty years are not uncommon. They are drought resistant and able to survive heavy grazing. There has been a shortage of seed of local ecotypes in recent years and the only seed available has been from farther west. The cultivar can be high yielding, but tends to be stemmy and shorter-lived (four to five years) and less tolerant of drought and grazing. Sainfoin is planted on land that cannot be irrigated, and commonly produces a hay crop for four to five years before exhaustion, although ten-year-old stands have been observed.

Wild meadows usually provide a single hay cut each year, although two are obtained from parts of the warmer northern valleys. In most of the province, lucerne usually gives two cuts, with three or four cuts made on favourable sites. Sainfoin generally gives a single cut. Vetches are sometimes sown in pure stand, but usually in mixture with barley, and may be cut for hay or grain.

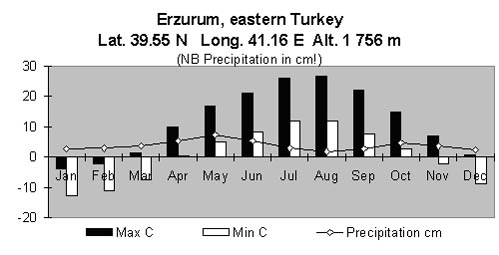

Figure 50. Temperatures and precipitation in Erzerum, Turkey

The different parts of the hay meadows, chayir, are almost invariably controlled by individual families as far as the right to make hay is concerned. There are, however, times of the year when the chayir is open to be grazed by all the village stock and not exclusively to those who have the hay rights. This is in early spring when stock are first brought out of their housing, usually April to mid-May. The dates vary somewhat with place and season, but is usually respected by village custom and confirmed by local authorities. After this date, the chayir is declared out of bounds to grazing stock. In autumn, after the hay crop has been carted, the chayir is again open to communal grazing of the aftermath.

Stubbles (aniz) and fallow land (nadiz), are customarily treated in a similar manner: all stubbles are usually open to communal grazing, although the actual rights of cropping are invariably exclusive to individual families. The same also applies to lucerne aftermath after the last cut of hay and subsequent to the last irrigation. The reason for this custom is that stock are herded communally in most villages, although they are housed by their individual owners.

For grazing land, mer'a, some time between May 5th and 15th, according to location and village custom, the stock leave the chayir for the village mer'a, which is grazing land open to communal use by all the village stock. For villages with no access to alpine pastures, there is no alternative but to continue to graze the mer'a in the immediate vicinity of the village throughout the summer. There is a tendency to graze outwards from the centre as the season progresses. In some places the pasture is exhausted long before the stubbles and aftermaths become available in September to give a brief respite before winter. In Horasan district, however, the custom is to graze the perimeter of the mer'a at the start of the season; thereafter the stock graze gradually inwards, leaving the range closest to the village until last.

Haymaking

After the stock have left the chayir the meadows are irrigated once or twice before the hay is mown. Each family is responsible for flooding its own meadows, while the maintenance of irrigation canals and drainage ditches (if any) is the responsibility of all users. The chayir are mown from early July onwards; often the herbage is more mature than ideal to produce the best hay from a feeding point of view, but bulk is what most farmers are seeking. Hay is still mown and baled by hand throughout most of the Province; by men with scythes on the flatter land and sometimes by men and women with sickles on very steep slopes. It is carted from the field with ox and horse-drawn carts, or tractors if available. There is little mechanization of the hay crop as yet, except for some places in the central valleys where small, self-propelled mowers and a few mechanical balers are in use on the larger units. Few farmers can afford this sort of capital investment.

Traditional methods are well suited to local conditions: the weather on the whole is excellent for making hay. After mowing, the hay is left in its swathes for a day or so before being raked into windrows. It is then rolled into tight cylindrical bales bound round with skilfully spun lengths of grass rope. Bales of wild hay are generally larger than those of lucerne; they vary between 25 and 30 kg in weight but are of a size that can be loaded onto a cart by a man working on his own. Carting and stacking hay is laborious and often overlaps with the cereal harvest; the bales may lie out in the fields for weeks until the workers have time to cart them. Their cylindrical shape provides some protection against occasional thunder-storms that are a feature of the season. The traditional rolled bales are also particularly suited to making good lucerne hay, since valuable leaf can be lost from loose hay. After the hay has been carted, the fields are usually irrigated before stock are allowed to graze.

Siting of stacks

Throughout the central valleys it is customary in most villages to stack the hay either on top of or immediately beside the owner's house and stables. In the southern districts, hay is normally stacked one or two hundred metres from the village itself, in a communal rick-yard. There appears to be good reason for this: the mainly Turkish-speaking villages of the central valleys seem to have lived in comparatively greater harmony with their neighbours than many of the villages in the southern districts, where a history of lawlessness and blood feud has been much commoner. In such a situation the danger of arson has been much greater, not only from without but from within the village community. Should a rival village set fire to your ricks at least your house will not burn down and should your neighbour have it in mind to burn your hay he will run the risk of burning his own at the same time. The final siting of the stack-yard in villages with a history of lawlessness is the responsibility of the local gendarmerie commandant.

Hay marketing

One of the most valuable crops in Erzerum province is hay. Not only as the most important winter feed, but as a crop to sell. This is true both of the hay from wild meadows and from sown crops. Some farmers in the central valleys grow hay as a commercial crop, and many other villagers sell hay if it is in excess of their own needs. Some also sell hay even when it is not in excess because they need the cash or because they feel that the cash value realized immediately by their crop is more use to them than the long-term return they might get by feeding it to their stock. Many villagers sell their hay and are prepared to keep their own animals, cattle in particular, on a mainly straw-based diet throughout the winter. The cattle in particular are slow-maturing at the best. The quickest and biggest profits are made by those who buy in three- to four-year-old animals from the mountain villages to fatten over a few months for slaughter, rather than by those who breed the animals in the first place. The villages have a need for cash in autumn to buy in provisions against the inevitability of being snowed in for days, if not weeks or even months on end.

Most of the hay is bought by merchants who transport it to Black Sea towns. There it is sold to small-scale farmers who produce hazel nuts and tea, but have very little forage. These small-scale farmers are comparatively prosperous, since they produce high-value crops; many have purchased Jersey or Jersey-type cattle. Although the merchants offer some price differential between legume as opposed to wild hay, there does not seem to be the same sort of differential between the best and worst grades of these two main categories.

|

[3] Based on Fitzherbert,

1985. |