Aquaculture in Africa has failed to achieve the expectations of many of its proponents. As the Continent prepares for the new millennium, it is faced with increasing food insecurity aggravated by rapidly growing populations, periodic environmental and climatic calamities, sometimes combined with civil and/or economic instability. Aquaculture has the potential to help offset the prevailing food imbalance. The looming question is how to realize this potential - what is the way forward?

In an attempt to answer this question, FAO organized the Africa Regional Aquaculture Review. The Review served as a forum to bring together aquaculture practitioners whose combined expertise was used to assess why aquaculture has not established a solid and economically viable foundation in Africa.

Specific goals of the Review were to:

Evaluate the past 30 years of aquaculture development efforts in the region with specific focus on aquaculture extension and public sector support for aquaculture.

Identify those elements that were and were not sustainable.

Elaborate a list of lessons learned.

Review the present status of aquaculture in the region through an analysis of different aquaculture systems.

Identify trends in aquaculture development.

Prepare an outline of key elements of a general aquaculture development strategy.

Important discussion points included:

aquaculture extension (including training);

government support to aquaculture development;

aquaculture production systems, small-scale; and

aquaculture production systems, medium-and large-scale.

The Review had the following specific outputs:

a list of aquaculture lessons learned, including specific notation of tactics that did or did not work;

recommendations for a structure for aquaculture extension;

recommendations for the level of government support for aquaculture development;

summary of current trends in small-, medium-and large-scale aquaculture systems;

an overview of prerequisites for commercial aquaculture;

an outline of key elements of a general aquaculture development strategy; and

a foundation for a network of practitioners to facilitate information exchange.

Opening

The Africa Regional Aquaculture Review was held in Accra, Ghana, from 22 to 24 September 1999. The Workshop was attended by 31 participants, 21 of them from 14 African countries, and others from FAO (headquarters and the Regional Office for Africa) as well as a representative from the International Centre for Living and Aquatic Resources Management (ICLARM). A list of the participants is in Annex 1.

Mr Bamidele F. Dada, FAO Assistant Director-General and Regional Representative for Africa welcomed the participants to the Workshop. He observed that aquaculture has the capacity to play an important role in fish production in Africa. However, it has not had a history of long-term successes. Thus, after three decades of developmental assistance and in spite of abundant land, water and human resources and the high demand for fish, Africa remains the region with the lowest aquacultural production in the world. He urged the participants to evaluate the past efforts, review the present status, identify trends in aquacultural development, and prepare an outline of key elements of a general aquacultural development strategy for the future.

Mr Mike K.S. Akyeampong, Ghana's Deputy Minister of Food and Agriculture, on behalf of the Ministry formally declared the Workshop open. In so doing, the Deputy Minister reiterated the importance his government in particular, and the Region in general, attached to aquaculture development. With fish being the major contributor of animal protein in the Ghanaian diet, and static or declining fish catches, fish farming has the ability to provide the country with much-needed supplies of fish.

Organization

The Review was organized into ten working sessions over the three-day period. A detailed agenda is presented in Annex 2. The first day was devoted to synthesis of reviews of selected national aquacultural programmes and trends in various culture systems. The second day was devoted to Working Groups on four subject areas, Table 1 shows the Working Group organization and composition.

The principal output of the Review was a detailed strategy outlining the way forward for aquaculture development in the Region. Box 1 presents a summary of this strategy.

Table 1. Working Group Composition

| Group A | Group B | Group C | Group D | |

| Subject | Aquaculture extension | Government support for aquaculture | Small-scale systems* | Medium-and large-scale systems** |

| Focal Person | Hishamunda | Entsua-Mensah | Jallow | Machena |

| Resource Person | Ziehi | Ridler | Brummett | Halwart*** |

| Members | Maguswi*** Ndjikara Wetengere Bashir | Shimang Kapeleta*** Kouam Rabelahatra | Kalende Janssen Kienta Ofori*** | Ayinla Gnakadja Mjomba Lomo |

(*) including existing traditional systems

(**) including mariculture

(***) person responsible for presentation at meeting

Box 1. Aquaculture development strategy summary

| Common elements of a strategy | |

| addressed to government decision-makers | |

| 1. | establish national development policies and an aquaculture development plan in consultation with stakeholders; |

| 2. | reduce expensive and unsustainable aquaculture infrastructure, specifically with a reduction of at least 50 percent of government fish stations within five years; |

| 3. | promote and facilitate the private sector production of feed and seed; |

| 4. | encourage credit for medium-and large-scale producers; |

| 5. | revise aquaculture extension, establishing a flexible and efficient structure to meet producers' needs; |

| 6. | advocate farmer-friendly existing technologies that use readily available culture species and local materials; |

| 7. | promote collaboration, coordination and information exchange between national and regional aquaculture institutions and agencies; and |

| 8. | facilitate the formation of farmers' associations. |

The following sections provide the framework of African aquaculture development, major issues facing this development and, as a consequence, important topics addressed by the meeting.

3.1 Historical Perspective

Aquaculture was introduced to much of the African Continent five decades ago1 as an innovation that would improve the economic and nutritional well-being of producers. Fish ponds were foreseen as an ideal component of integrated farming systems, a fish crop grown using by-products from the home and farm. Indeed, from Kenya to Sierra Leone thousands of ponds were built, many only to be abandoned after a few years of meagre production.

In July 1975, FAO organized the First Regional Workshop on Aquaculture in Africa (FAO, 1975). This workshop recognized the importance of aquaculture and the high priority attached to it by many governments. It was further noted:

“failures of some of the ill-conceived programmes during the early part of the century have continued to remain a major constraint in convincing the farmers and investors of the economic viability of aquaculture. Insufficient appreciation of the basic requirements of an effective aquaculture development programme and consequent inadequacy of governmental support activities, have handicapped the orderly and rapid development of the industry.”

Following the Workshop, there was increased aquaculture activity with nearly every African country launching donor-supported fish farming projects.2

This was followed by the 1976 FAO-sponsored World Technical Conference on Aquaculture, held in Kyoto, Japan, which established an approach to aquaculture development which has been labelled the “Kyoto Strategy” (FAO, 1976). This was a technology-centred approach that focused on the transfer of proven technologies through regional programmes.

In 1986, ten years after the Kyoto Strategy became the guideline for aquaculture development, UNDP, FAO and the Norwegian Ministry of Development Cooperation undertook the Thematic Evaluation of Aquaculture to evaluate the results achieved by utilising this approach (FAO, 1987). The Evaluation found that, in general, successful projects: (a) had been preceded by a careful selection of species and culture system combinations; (b) had lasted for a long period (a decade or more) and (c) had been supported by strong government commitment. However, they also found that projects tended to concentrate on physical results as opposed to transferring know-how.

The Evaluation concluded that “the purposes and capabilities of the prospective producer are the main concern of those attempting to introduce or modify aquaculture.” When assessing the potential of aquaculture, it is not sufficient to identify the physical and biological constraints. The Evaluation determined that potential is created by “the combination of the producer's desire to be an aquaculturist (even if only part time) and the consumer's wish for aquatic products”.

As regards aquaculture in Africa, the Evaluation assessed impact and noted:

“Impact achieved through UNDP/FAO technical assistance to aquaculture is most visible in Africa. Primarily this has been achieved through the reintroduction of pond-based tilapia culture. Efforts have been successful where assistance has been continued for a long period, generally not less than a decade. A recurring weakness, which places sustained impact in jeopardy, is the fact that rural freshwater aquaculture in most countries is still dependent upon government support, particularly for seed. However, fish produced has brought nutritional benefits has brought nutritional benefits in the producing areas. As this production has not led to direct exports, and is unlikely to have reduced imports, there has been no impact on earnings of foreign currency.

It is recommended that assistance to aquaculture in Africa continue to emphasise the development of extensive and semi-intensive tilapia culture, explore opportunities for establishing culture-based fisheries, include resources for education and training counterpart staff”.

The Evaluation recommended that the Kyoto Strategy should be reconsidered because UNDP/FAO could not continue to meet the needs for financial and technical assistance. Thus, future efforts should:

focus on a specific combination of species and aquaculture systems;

identify geographical regions which correspond to specific species/systems combinations which should receive priority attention;

pay close attention to recipient government's effective commitment to aquaculture; and

ensure systematic monitoring and evaluation of impact generated by the assistance provided.

African aquaculture was also a topic at the 1988 FAO Expert Consultation on Planning for Aquaculture Development (FAO, 1989). This Consultation concluded that output from sub-Saharan Africa was still very low, with Nigeria, Côte d'lvoire, Kenya and Zambia being the most important contributors to the Region's estimated 10 000 tonnes of aquaculture production. Most of this production was attributed to small-scale semi-intensive farming of tilapia, with few large-scale commercial ventures able to demonstrate long-term economic viability. Ineffective or non-existent policies combined with inadequate infrastructure, poor extension support and unavailability of inputs (including seed, feed and credit) were cited as major problem areas. It was recommended that seed production should be privatized and resources devoted to upgrading extension through training and improved information flow to producers.

Five years later, FAO, assisted by other collaborators, assembled a series of 12 national aquaculture reviews from countries3 responsible for 90 percent of the Region's aquaculture production (Coche et al., 1994). These reviews identified major constraints on the continental level as:

no reliable production statistics;

credit availability limited for small-scale farmers;

very low technical level of fish farmers;

unavailability of local feed ingredients;

lack of well-trained senior personnel;

prohibitive transport costs; and

lack of juvenile fish for pond restocking.

Today Africa's fish and shellfish aquaculture production is only slightly over 110 000 tonnes. Although this figure represents over a 60 percent increase during the previous decade (FAO/FIDI, 1999), it is only 0.4 percent of the world total. In spite of the Region's natural endowments, including untapped land, water and human resources, Africa remains in an aquaculture backwater.

Annex 4 summarizes past aquaculture experiences of the seven countries selected for review and Annex 5 encapsulates the present aquaculture situation in each. It is clear that the same issues cited above continue to plague aquaculture development. Annex 6 provides some insight into what aspects of previous development efforts seemed to work and what did not.

3.2 Aquaculture Policies

During the zenith of donor support to African aquaculture, in the 1960s and 1970s, few countries had national aquaculture development policies. This often led to a haphazard pattern of development, sometimes with different areas of the same country implementing different aquaculture programmes depending upon which donor was active where. This situation was aggravated by the fact that most donors operated on a relatively short planning horizon (i.e. two to five years) which did not favour longer-term strategies.

Another factor adversely affecting policy-making was the fluid institutional setting of national aquaculture programmes. Across the region aquaculture has been assigned to a great variety of institutional “homes”; sometimes in the Ministry of Agriculture, other times with forestry or livestock agencies; even within the Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism in the case of Tanzania. At one time, aquaculture in Congo (Brazzaville) was simultaneously assigned to two different ministries. Frequently agriculture research and extension found themselves in different ministries, confounding efforts to coordinate the two activities.

In today's environment of reduced donor support, concise and focused policies are essential to channel limited resources. Nonetheless, many countries still completely lack such policies or have ineffective policies that outline generalities without adequate specificity for implementation.

3.3 Aquaculture Public Infrastructure

Hundreds of fish stations have been built across the Region. Considering a few examples, Cameroon has ten stations and 22 hatcheries (most of which are presently quasi-abandoned), Nigeria reports 20 Fish Seed Multiplication Centres (only eight under full operation) and Côte d'Ivoire cites 19 hatcheries along with three other government aquaculture facilities (five of the total no longer functioning). Some stations are large government farms, while others are small units of only a few hundred square metres. Regardless of size, all stations impose demands on government.

Habitually stations were foreseen as having one or more of the following roles:

supply of fingerlings to local fish farmers;

serve as demonstration sites;

serve as training centres, especially for farmer training sessions;

produce food fish for sale; and

serve as research centres.

In today's climate of austerity, the validity of these roles must be reassessed. It can be argued that fingerling and food fish supplies should come from the private sector while private farms also make the best demonstrations. Thus, with a more channelled vision, stations could be seen as being justified only for training and research. Comparatively few stations would be needed for these two tasks. This means that the surplus should be transferred to the private sector or disassembled.

Several countries have embarked upon programmes to privatize government stations. Yet the modalities remain to be clearly elaborated. If stations are to be sold or leased to private producers, they must have a certain minimum economic size (i.e. production potential) to entice investment. Those facilities below this minimum size must then either be razed or transferred to new owners whose motives are more than economic (e.g. NGOs, youth groups, etc.).

3.4 Feed

It is apparent that the quality and quantity of nutrient inputs will, to a large extent, determine yield. In view of the lack of reliable supplies of fish feeds, most small-scale semi-intensive systems have relied upon natural food (e.g., zoo-and phytoplankton) production enhanced with fertilization (most often organic fertilizers) and supplemented by farm and household by-products (e.g. kitchen scraps, spoiled produce, etc.). Such systems have demonstrated their productivity when farmers use an adequate variety of inputs in sufficient quantity. Variety is important since it is rare that any individual input will be available in large enough quantities throughout the year. Hence the key is to use a lot of whatever is available.

However, the promotion of semi-intensive systems does not directly address the issue of feed. In numerous countries formulation of more complete fish feeds has been attempted. A typical example would be to prepare a crumble from blood, rice bran and oil seed cake, at times adding a vitamin pre-mix. This would be sun-dried and have an acceptable shelf life. The problems with such relatively crude feeds are:

they are comparatively inefficient, often having a conversion ratio of 4–6 kg of feed per kg of fish;

the preparation process limits the quantity that can be produced per unit of time;

often supplies of ingredients are irregular and unreliable; and

when all costs are considered, including transport to the fish farm, these feeds are frequently not cost effective.

More commercially produced feeds are available in some countries (e.g. Nigeria, South Africa, Côte d'Ivoire and Zimbabwe) but these require the country's agricultural sector to produce large quantities of by-products that can be available for feed fabrication. Many countries in the Region do not have such supplies available. Yet, as one looks to the future, current forecasts for economic growth in the twenty-first century mean that more and more countries should be having increased agricultural production providing opportunities for more animal feed production.

3.5 Seed

Fingerling production is another chronic problem with several important dimensions: quantity of seed produced, quality of seed produced, cost of seed produced and means of seed distribution to farmers. In the aggregate, these factors created the “scarcity syndrome” and have led to a situation where farmers throughout the Region have been forced to wait long periods before receiving scarce fingerlings, some times abandoning their ponds in the interim. Moreover, when the fish did arrive they were often of poor quality, leading to disappointing harvests and abandonment of the fish pond.

When viewing this dilemma, one should recall one of the basic principles of choosing an aquaculture species: its “reproductibility”. A prime criterion for a culture organism is that it can easily reproduce in captivity. This implies that the fish's reproductive cycle can be satisfactorily completed in a culture situation. There should also be the underlying understanding that this implies that the fish can be reproduced using means/technologies appropriate for local conditions. Fish that require sophisticated techniques and/or imported materials to reproduce should not be considered as suitable candidates.

Although a wide variety of fish have been tried in culture environments, the most common pond-raised fish in the Region are tilapias (i.e. various fish from the genera Oreochromis and Tilapia), common carp (Cyprinus carpio) and catfishes (i.e. Clarias, Heterobranchus or their hybrid). Initially both the carp and catfish were victims of the scarcity syndrome, both requiring extraordinary hatchery techniques. Fortunately, today it is now possible to produce both carp and Clarias seed using farmer-friendly techniques. Carp in Cameroon and Rwanda are spawning naturally while Clarias fingerlings are being produced by farmers in Kenya and Congo (Brazzaville).

In spite of this, tilapia remains the most frequently cultured fish, and the fish about which more complaints are made with respect to small harvest size, stunting, etc. To attempt to address this problem, a variety of techniques have been used in countries around the Region, including Ghana, Côte d'Ivoire and Zambia, to raise all male tilapia which grow to a larger size (than females). Hand sexing to obtain an all-male stock is the most user-friendly method. At some sites sex reversal using methyltestosterone is employed, but this requires access to the hormone and slightly higher technology.

Other aquaculturists have sought to improve tilapia systems by improving the fish, either by identifying a new culture species or by genetically improving existing culture species.

It is highly probable that actual mixed-sex tilapia systems utilized by a majority of African farmers could be significantly improved if the quality of seed is improved. The customary techniques diffused by many small-scale aquaculture projects were to harvest the pond after six months, selling or eating the larger fish and keeping the smaller individuals for restocking. However, unless extreme care is taken, the individuals that are used for restocking will already be sexually mature and begin reproducing almost immediately after stocking.

A possible alternative to this method is to hold brood fish in a net enclosure (happa) where their spawning can be closely monitored. In this way the age of the fingerlings will be well known and there will not be a risk of stocking sexually mature individuals. The happa could be placed in the farmer's grow-out pond or some farmers could specialise in seed production. In lieu of happas, small earthen ponds could be used.

A similar technology to ensure known-age fingerlings is to scoop up “clouds” of fry as they school in the shallows or to remove young fry from their mother's mouth. In either case, the fry then need to be transferred to some type of rearing container and well fed.

Regardless of the technology chosen, it can be concluded that on-farm (private) production of fish seed is now feasible for the most common culture species. Given carp's preference for more temperate climates, the most suitable culture fishes should continue to be Oreochromis niloticus (Figure 1) and Clarias gariepinus (Figure 2).

3.6 Credit

Credit, or more precisely the lack thereof, is often cited as a major constraint to aquaculture development. Several projects attempted to deal with this issue by providing farmers with credit using project funds. Unfortunately the payback rates were extremely low and the activities ended in failure. A conclusion derived from these experiences is that projects themselves should not be directly involved in providing credit.

Figure 1. Oreochromis niloticus

Figure 2. Clarias gariepinus

Before progressing further on this subject, it should be noted that thousands of small-scale fish ponds have been built throughout the Region with no credit provided. Credit would be helpful in any situation, but is most probably only necessary when a certain scale of operations is being considered.

Commercial lending institutions should be the providers of that credit required. However, these institutions seldom offer credit to fish farmers, believing fish farming to be a high risk or unprofitable activity. It is, therefore, important to educate individuals from these institutions as to the real profit potential of aquaculture. It would also be helpful to establish links between these individuals and an aquaculture officer from the appropriate ministry. This person could technically vet each request for credit, his or her approval going a long way in ensuring acceptance of the loan.

In addition to education loan-givers about the advantages of aquaculture, traditional (informal) credit mechanisms should be explored. Many communities have well established procedures for assisting members financially.

The Africa Regional Aquaculture Review also served as an instrument for collecting information on aquaculture trends in the Region. These data were compiled in a paper that provides a regional overview.4 This paper reviewed current trends in four major aquaculture systems in Africa (i.e. small-scale, culture based, traditional and medium-to large-scale systems) with a view to analysing and understanding the problems that have dogged aquaculture development on the continent for so long. It is hoped that this analysis of past experiences and mistakes will form the basis for developing new insights, through which new efforts will be channelled leading to a predictable growth of the sector.

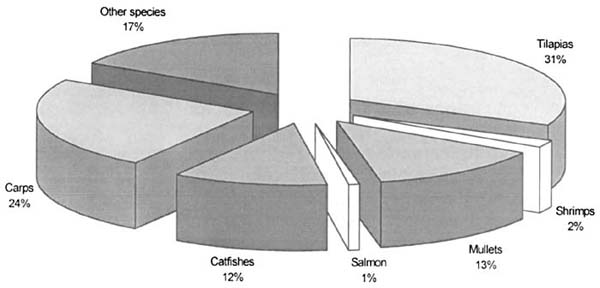

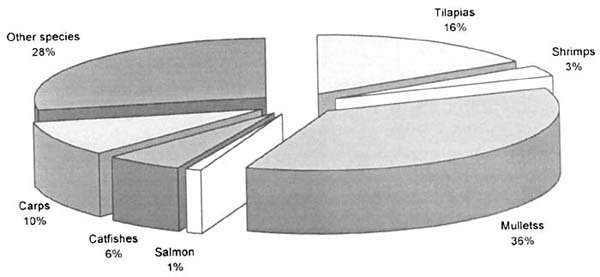

An important part of the paper included an analysis of regional aquaculture statistics (FAO/FIDI, 1999). Based on these statistics, Figures 3a and 3b present the regional aquaculture situation in terms of total production and the value of this production, broken down by major culture species. The four graphs comprising Figure 4 use the same statistics to show production trends for 15 African countries for the period 1988–1997. Only five of the 15 countries (Central African Republic, Côte d'lvoire, Madagascar, Malawi and Zambia) show positive trends (slope) over the ten-year period.

The existing statistics are not immediately applicable to the structure of the trends analysis since there is no differentiation between small-and large-scale systems. In fact, production systems tend to be categorized by three types of determinants: relative size (e.g. small-, medium-or large-scale); relative intensity (e.g. extensive, semi-intensive or intensive); and motivation (e.g. subsistence vis-à-vis commercial, the latter possibly comprising “artisanal” and “industrial” levels of output).

Nonetheless, the author of the Trends paper indicated that the analysis of the regional aquaculture statistics showed that:

African aquaculture production contributes little to global production. In fact Africa is the least advanced of all the continents in terms of aquaculture production.

China continues to dominate in global aquaculture production; 67 percent of global finfish production coming from China alone.

Global rate of expansion in aquaculture production continues to outpace growth in the capture fisheries sector. The world's wild fish catch has stagnated at about 80 million tonnes since the late 1980s. Catches from inland fisheries in Africa have also stagnated, and any increase from production from African marine waters is not likely to make much difference.

The increase in the value of fish combined with increased production on both a global and African scales implies a continued sustained demand for fish and fish products. This is quite expected, particularly for Africa where population growth rate far exceeds the rate of food production.

This also implies that aquaculture still has the potential for further development on a world scale.

4 Analysis of Current Aquaculture Trends in Africa, C. Machena, in press.

CONCLUSIONS

The paper's main conclusions and recommendations are:

African countries need to increasingly realize that aquaculture is a tool that has the potential to contribute significantly to the development of rural areas. Small-scale farming contributes to the intensification of agricultural activities by enhancing synergies with crop and livestock systems. The farming season is extended, crop diversity is enhanced and household income increases.

As rural communities constitute a large component of the population of African countries, a wide-scale adoption of aquaculture practices at the level of the community contributes significantly to improved general population health and poverty alleviation.

Small-scale farmers have rural social constraints that affect their needs, priority assessments and aspirations. But these are poorly understood. These constraints are complicated further by being location and agro-ecological specific. The on-farm approach has the potential for resolving these constraints through involving the farmer directly by participating in the design and testing of improved farming practices.

An outcome of the on-farm approach is capacity building. Organizational skills, problem-solving initiatives, short-and long-term planning, flexibility to make choices are other skills imparted on the farmer.

Small-scale production systems

The acadja system is much more productive than small-scale pond systems, even those that are integrated with other agricultural activities. Productivity is even enhanced with integration with livestock systems. It therefore has potential for widespread use and should be introduced into other regions. The use of alternatives to tree branches should promote the sustainability of the practice.

Surface water bodies in southern Africa have the potential for increased fisheries production in rural areas. Efforts to understand the systems better and to promote community-based management systems should be continued.

Figure 3a - African aquaculture production in 1997: percentage contribution of the major species groups to the total quantity produced

Figure 3b - African aquaculture production in 1997: percentage contribution of the major species groups to the total value.

Figure 4. National aquaculture production figures for the period 1988 to 1997 for Benin (BEN), Cameroon (CMR), Central African Republic (CAF), Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Côte d'lvoire (IVC), Ghana (GHA), Kenya (KEN) Madagascar (MAD), Malawi (MLW), Mali (MLW), Nigeria (NIR), South Africa (RSA) Tanzania (URT), Zambia (ZAM) and Zimbabwe (ZIM).

Annual Production (mt) from 1988–1997

Annual Production (mt) from 1988 to 1997

Annual Production (mt) from 1988 to 1997

Annual Production (mt) from 1988 to 1997

The Executive Summary of the background document prepared on the subject of Public Sector Support appears in Annex 7. The following three sections reflect the conclusions of the Working Group on Public Sector Support as well as plenary discussions on this topic.

5.1 Present situation

The present situation can be typified by a general inadequacy of government support to aquaculture with a result that many services and facilities are either functioning at reduced levels or dysfunctional. To a large extent, this situation is a result of a dependence on donor support. With many areas now suffering from donor fatigue, few governments have been able to allocate sufficient resources to keep national aquaculture programmes fully operational.

It was specifically determined that there is at present a need for:

aquaculture policies (national development plans);

national aquaculture information systems;

demand-driven research that includes the socio-economic aspects of research and development;

reinforced linkages between research and development;

adapted research on brood stock management and that governments take responsibility for brood stock management;

regional or subregional research and/or training centres

training at all levels including practical training of farmers, technicians and extensionists organized on stations and, among other subjects, including;

Teaching farmers how to produce their own seed

Teaching farmers how to specialize in seed production

involving NGOs in training and development.

It was also noted that:

seed costs, as those for other inputs, are dependent on supply and demand - as supply increases, prices should fall;

there are social benefits of aquaculture which need to be acknowledged by governments and economists;

public sector priorities should be to:

support the private sector for seed production and assume a role in quality control of product

support the formation of farmer groups

target small-scale subsistence producers;

privatization is encouraged but its modalities are not well defined.

5.2 Lessons learned

Based on past experiences, the following lessons should be noted and incorporated into national development policies:

field activities should be decentralized on the basis of agro-ecological zones;

major government fish culture stations should be given financial autonomy and put under good management;

public infrastructure should ultimately be self-supporting;

the frequent transfer of personnel has greatly hampered development plans and affected sustainability;

farming inputs should not be distributed free to farmers but should have at least a subsidized price;

the age of stocking material (fingerlings) must be known if good results are to be obtained;

technology should not be based on imported commodities (e.g. hormones, feeds, etc.);

selected culture species should be able to be reproduced by farmers themselves;

an aquaculture development plan should help focus development geographically and facilitate control and evaluation (monitoring) of the programme;

on-station research to support small-scale aquaculture development should be based on inputs commonly available to small-scale farmers and it should be farmer-driven through joint activities;

sociocultural surveys should be conducted before introducing a new technology to a region.

5.3 Recommendations for future strategy

There are five particular areas requiring government support: (i) policy and legislation, (ii) stations, (iii) seed and feed, (iv) research and (v) training. Recommendations are given below for each of these five areas.

POLICY AND LEGISLATION

Most countries do not have an aquaculture development plan, and such a plan is necessary to guide future progress.

Governments should develop plans for aquaculture that give a sense of direction for development with clear outputs, time frame and coordination of all national activities. Within these plans, high-priority aquaculture districts should be selected and used as focal points for development and extension.

National advisory committees for aquaculture should be established in fisheries departments or other relevant government agencies. Committee composition should reflect the interests of all stakeholders.

Networking should be developed at the national and regional level. The national networks would be units within the regional networks.

National aquaculture databases should be established.

For commercial aquaculture, it is necessary that regulatory instruments should include environmental impact assessments.

For commercial aquaculture, property rights could be a problem and governments should address this while taking into account the interests of the local communities.

Commercial aquaculture zones should be set aside; some areas might even be considered as free zones for export processing.

Aquaculture should be integrated with agriculture activities through extension services.

STATIONS

Some stations in the region have the potential of covering their running costs and where possible this should be encouraged. Incentives should be offered to those involved in such cost-recovery.

Governments should be encouraged to gradually disengage from running aquaculture stations and transfer these to fish farmer associations. They should initiate reduction of number of stations immediately, with a reduction of 50 percent or more in five years.

Governments should improve management through private sector involvement, giving first option to the local communities. Where this is done and stations are under private sector management, governments should take care not to aggravate income inequalities.

SEED AND FEED

As aquaculture develops, governments should, gradually (e.g. over a period of five years) disengage from fingerling production and distribution while keeping responsibility for the management of broodstock through research institutions and universities.

Fish farmers associations should be encouraged to be service providers for feed and seed. With feed this can be done through special arrangements between fish farmer associations and local animal feed manufacturers which will make feed production more cost-effective.

Continued subsidies on feed, seed and other inputs are not sustainable. Other incentives such as loans with low interest rates should be considered for their applicability. Such loans could be given through either farmers' associations or organized women's groups or other local organizations that should provide the loan guarantee.

Professionals and practitioners should foster strong relations among African fisheries scientists through the formation of a self-supporting African Fisheries Association. The association should have a listserve and interact through e-mail and mailing lists.

To stimulate the private sector, aquaculture viability must be demonstrated. This may involve preparation of business plans by government officials or demonstrations using model commercial farms.

RESEARCH

Government should fund research.

Research should be relevant to the region and to the current development programme.

Research institutions and universities should recognize the potential conflict between demand-driven research and research needed for promotion.

Private sector research funding has potential and should be encouraged, i.e. for seed development and feed development by entrepreneurs.

The subregional “centres of excellence” of research in aquaculture should be encouraged and preferably determined by a competitive process.

Research in aquaculture should include biological, socio-economic and environmental aspects.

For applied aquaculture research, there should be a holistic approach that incorporates community participation.

There should be more on-farm adaptive trials and increased farmer participation in research.

Research finding should be made available to farmers directly or through extension.

TRAINING

Each aquaculture project or programme should have a training component for fish farmers.

Nationally, there should be more specialized training for aquaculture at the tertiary level.

There should be a pooling of resources, both financial and human, in the subregion to promote centres of excellence beneficial to all countries involved.

Information on the training institutes in the region should be regularly made available, even on the Internet.

Aquaculture training should reflect the developmental needs of each country.

Aquaculture centres should take account of existing new technologies in their training programmes.

There should be a periodic review of subregional training programmes.

GENERAL REMARKS

Government stations: stations often serve one or more of five common purposes: fingerling production, foodfish production, demonstration centres for extension activities, training and/or research. The first three purposes should gradually be disengaged from government. During the period of disengagement, training should be provided to private sector units such as fish farmer associations and entrepreneurs, for taking over such stations in a sustainable way. Government should maintain its support for training and research.

Regional centres of excellence: a maximum of five centres for the Region should suffice, with two in West Africa, one in Central Africa and two in the southeastern subregion. Where a centre has capacity to combine both research and training, it should be considered to have both at one centre because research activities can greatly complement training. An evaluation of existing centres should be undertaken with a view to establishing each's role in the proposed new setting. Terms of reference for the evaluation should be developed at a regional or subregional basis, that is, Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), etc. reflecting in-depth appreciation of the issues involved-modalities, languages, existing and potential capacity, political will, etc.

Advisory committees: national committees composed of both potential and existing stakeholders should be established to guide aquaculture development. These could be decision-makers, policy-makers, academics (socio-economists, policy analysts, agriculture scientists, biologists), entrepreneurs, fish farmers and representatives of their associations, women's groups or their representatives, bankers, fishers, NGOs, etc. Membership to the committee should be renewed within a period not exceeding three years to encourage dynamism.

Database: it is important nationally to identify an institution, university, etc. as a focal point for analysis and custody of statistics in a database. The database will input into the subregional database and in turn this will input into a regional database. Information technology hardware and peripherals must be considered as paramount when selecting the national focal point.

Information: there is a strong need for the promotion of information exchange throughout the region, in research, development, training and extension. This could be best done through networking. It would also contribute to reinforcing linkages between research and development at both national and regional levels.

The Executive Summary of the background document prepared on the subject of Public Sector Support appears in Annex 8. The Working Group on Aquaculture Extension examined past experiences with the development of aquaculture extension as well as its present status. Lessons learned were then derived and used in elaborating recommendations for a future strategy.

6.1 Past experiences

Some past experiences were considered as positive (workable) while others (negative) reflect approaches that should not be repeated.

(a) Workable experiences

Aquaculture is now known throughout Africa as a result of previous extension efforts.

Adoption/acceptance, even if on a modest scale, has been noted in most countries.

Initial experiences with farmer to farmer extension approaches, including cooperatives and farmer groups, have indicated that this approach might be a successful way to transfer aquaculture messages.

Accepted cultured species introduced by extensionists include: tilapias, catfishes, common carp, penaeid shrimps.

(b) Negative experiences

Donor conditions have often been stringent, advocating systems that exceeded countries' capacity to sustain them.

Research/extension collaboration has been weak and conflicting objectives have been noted.

Unified extension system has apparently led to a dilution of aquaculture support to farmers since generalist agents frequently do not have any aquaculture training.

Credit schemes for small-scale farmers have never been satisfactorily put in place and their need is questionable.

6.2 Present situation

The present extension structures tend to fall into one of three categories:

Dedicated (project) extension approach which is:

donor-driven

too expensive

unsustainable

Unified extension approach which often:

is imposed

has limited capacity in specialities such as aquaculture

has limited technical staff

should be tailored to needs and potentials, but frequently is not

still requires extension agent transport which is often provided with donor funds

Private extension approach which is:

difficult to envision in most countries at this moment, but

should be kept in mind as an option

Furthermore, aquaculture extension can be typified by the following:

extension often remains donor-supported;

government support is insufficient to maintain an effective aquaculture extension programme;

most government stations are non-operational;

farmer to farmer extension approach is being further experimented in an increasing number of countries, either as a formal (part of extension method) or informal (“spontaneous”) mechanism;

the farmer-to-farmer channel implies shared responsibility with farmers taking some responsibilities, which in turn requires a change in mentality);

seed and feed supplies are inadequate to meet demand in most, if not all, countries;

collection systems for aquaculture statistics are poor and those statistics available often unreliable;

networking at both national and regional levels most often does not exist.

It is, therefore, necessary to:

focus on small-scale (subsistence or commercial) where need is the greatest;

establish research/extension linkages;

concentrate extension on high potential areas; and

pay attention to gender and other sociocultural aspects of aquaculture development.

6.3 Lessons learned

Extension duties should not be combined with law enforcement.

Fish farming in low productivity “barrage” ponds should not be encouraged.

Extension efforts should be focused on small-scale model farmers operating under favourable conditions (water and soil, interest and dynamism, experience with other resources, etc.).

From such model farmers, the farmer to farmer extension approach should be developed through group demonstrations, field days, advice, fingerling production/sale, etc.

Credit is not necessary and hence should not be provided to small-scale integrated farmers.

Access to land is an important issue that needs careful analysis.

Marketing is also another issue that is often overlooked but can be critical to the establishment of aquaculture operations.

Commercial aquaculture should be promoted whenever possible.

Any intervention should have well defined objectives.

6.4 Recommendations for future strategy

(a) Extension

Private sector involvement should concentrate on information dissemination, on seed production/distribution and on feed supply.

Government involvement should be restricted to training, provision of extension materials, monitoring, development of policy guidelines and improvement of broodstock production.

(b) Training

It should take place both at regional and national levels, mostly though short-term sessions, study tours and exchange visits.

(c) Technology development

Communications, including e-mail, Internet and networking, is essential to harmonize the development of aquaculture technologies.

Production technologies that require attention include: seed improvement, feed production and supply, pond construction and management, integration and harvesting.

Post-harvesting technology is also important and will become more so as production increases.

The above should be attained through

(d) Use of government facilities

Most of government facilities should be leased to the private sector or to farmers groups.

It will be necessary to retain a minimum number of farms/stations for genetic improvement of stocks.

(e) Aquaculture extension structure

Although it is difficult to suggest a uniform structure for all countries, a model inspired from the Central African Republic experience, and based on the structure proposed hereunder, would be likely to be effective in most cases.

Farmer-to-farmer approach (farmers' groups) is the foundation of this structure.

Minimum government intervention should be required for the new structure.

It is desirable that there be a limited number of intermediate levels between top and bottom levels of the new structure.

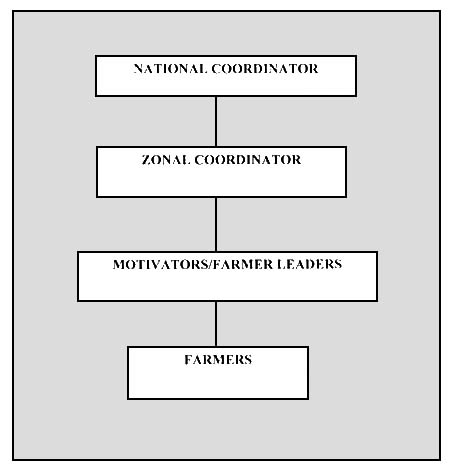

Figure 5 indicates the recommended structure diagrammatically.

Figure 5. Proposed structure for aquaculture extension.

It is acknowledged that it is difficult to find a structure that will fit all situations. However, the structure presented in Figure 5 is flexible and can be modified to meet local needs. It is based on the principle of effective farmer-to-farmer communication channels. The Zonal Coordinator is an aquaculture technician who works directly with a carefully selected number of Farmer Leaders, who in turn assist a number of farmers through farmer-to-farmer channels.

Zonal Coordinators do require some means of transport; perhaps bicycles if the Farmer Leaders in their zone are not too scattered, motorized transport (e.g. motorcycles) if the density of Farmer Leaders is lower. They will interact with the National Coordinator via telephone or other electronic communications if they are available; otherwise they will have to meet periodically with this person.

The proposed structure could be compatible with the Training and Visit (T&V) approach employed by a number of unified extension systems. The Zonal Coordinator is similar to the T&V Subject Matter Specialist; the difference being that this person deals directly with Farmer Leaders rather than working through a community-level generalist extension agent.

Given the limited number of staff qualified to be aquaculture Zonal Coordinators in most countries, this approach would require an extension methodology that focuses effort on high potential areas.

In some countries it is foreseeable that the Farmer Leaders could ultimately evolve into private extensionists, especially if these individuals were directly involved in private feed or seed production where they would have a personal stake in promoting aquaculture development.

Small-scale integrated aquaculture consists in extensive to semi-intensive utility-oriented aquatic systems operated by a household and integrated to varying degrees with other agricultural enterprises. Its overall goal is food security and well-being. Its purpose is to provide for:

Felt needs including food, income and efficient use of land and water resources.

Unfelt needs including stabilization of farm production over time, reduction of soil erosion and increased plant coverage and maintenance or increase of biodiversity as well as to foster rural development.

7.1 Present situation

Small-scale systems include:

small fish ponds;

traditional fish aggregating systems (e.g. acadjas);

traditional fish retention systems (e.g. community/individual ownership of fish holes/trenches);

cages and pens;

paddy fields stocked with fish;

small water bodies and culture-based fisheries (community ownership).

Small-scale systems are typified by:

relatively low density of farmers (i.e. scattered farms);

relatively low production;

use of family labour along with household and farm inputs.

7.2 Lessons learned

Previous experiences indicate that there has been:

a lack of farmer participation in development programmes;

frequent pond site selection errors;

a lack of government policy leading to donor-driven interventions which usually cannot be sustained at the end of projects;

a lack of government support leading to dependence on donor support for projects;

weak extension support;

a situation where farmers are usually not organized/involved in data collection;

a lack of technological flexibility;

inappropriate methods of technology transfer;

a lack of coordination in development assistance (overlaps in rural development); and

a lack of socio-economic indicators to monitor progress.

Furthermore, it is noted that:

private sector involvement in input (seed, feed, etc.) supply is demand driven;

centralized and subsidized fingerling production and supply are disincentives to private sector involvement and create shortage of seed.

development of small-scale aquaculture should be based on locally available resources, in particular construction equipment/materials, fish seed and feed;

fish seed should be produced locally, in rural units involving small-scale farmers; and

the integration of animal husbandry with small-scale aquaculture is often inappropriate for smallholder farmers.

7.3 Recommendations for future strategy

Small-scale aquaculture systems can contribute to food security if the following recommendations are implemented:

Government should formulate realistic and appropriate aquaculture policies that will adequately support small-scale systems.

Rural aquaculture development programmes should have clear priorities around which government will guarantee long-term support.

Strengthening the technological development transfer procedure is necessary.

Farmer participation, organization and involvement in data collection, programme development and execution/monitoring should be enhanced.

Technology packages should be demand-driven and flexible; including fingerling production, broodstock management, extension services, etc.

The following sections present a strategy for small-scale aquaculture development in the Region, including issues relating to: (i) policy; (ii) government stations/infrastructure; (iii) extension; (iv) small-scale aquaculture; (v) training; (vi) research; (vii) information; and (viii) statistics.

These sections also include topics relating to public sector support (Section 5) and aquaculture extension (Section 6) since it has been stated that government support (including extension) should focus more on small-scale operations, thereby placing government-related issues within strategies for small-scale aquaculture development.

POLICY

Establish aquaculture development policy including privatization of fingerling production, focused extension and participatory approach.

Create a national Aquaculture Advisory Committee.

Elaborate a national Aquaculture Development Plan.

GOVERNMENT STATIONS/INFRASTRUCTURE

Initiate reduction of number of government stations.

Reduce by at least 50 percent the actual number of government stations.

Select and retain stations for research and training (government funding).

Promote private sector involvement and better management through long-term lease.

EXTENSION

Focus efforts on selected areas.

Revise extension structure.

Promote farmer-to-farmer communication.

Promote Farmers' Associations.

SMALL-SCALE AQUACULTURE

Focus on limited number of culture organisms.

Focus on locally available inputs and existing technology.

Develop socio-economic indicators of impact.

Develop better understanding/knowledge of traditional systems and their potentia for enhancement.

TRAINING

Evaluate regional needs and capacities (centres of excellence).

Evaluate national needs and capacity at all levels.

Develop national or intraregional practical training (field days, etc.) for farmers, extensionists, administrators and decision-makers.

RESEARCH

Improve national coordination.

Increase involvement of universities.

Develop demand-driven research agendas through improved linkage with development.

Incorporate social, cultural and economic aspects into research agendas.

Establish national brood stock management programme.

Establish regional specialized research network (centres of excellence).

INFORMATION

Establish informal exchanges.

Establish national information network.

Establish regional information network.

STATISTICS

Revise and improve data collection.

Increase use of Farmers' Associations in collection of statistics.

Establish national database.

9.1 Present situation

Insufficiency of seed supply

Insufficiency of feed supply

Unavailability of credit focused to aquaculture

Inadequate technical support

Inadequate communication/information management system

Inadequate applied research for brood stock and feed (appropriate technology)

Inadequate focused regional human reserve development programme

For marine aquaculture in particular:

Unavailability of adequate sheltered bays

Siting of marine cages in conflict with the tourism industry

Tendency to import rather than to develop technology

Great lack of sufficient trained personnel

Lack of training institutions

Trend for production of luxury food items such as shrimps, oysters, mussels and abalone

Mostly export-oriented activity

Development can clash with tourism development in coastal areas

9.2 Lessons learned

Advantages derived from large-scale operations include:

Possibility to access credit on national markets or offshore

Possibility to meet own feed/seed requirements

Ability to take risk

Emerging awareness of potential of large/medium size operation

There is a lot more happening on the ground than is reported in literature

Unlimited local/foreign market

Possibility for foreign exchange income

Increased food security

Potential for aquaculture expansion

Possibility for import substitution (Nigeria)

Policies for structured development (code of conduct)

e.g. support of private sector in Madagascar

Inability/difficulty by private sector to access land e.g. Kenya

Focus is on a few indigenous local fish species

A high degree of integrated farming takes place

There is the need for credit facilities at subsidized interest rates.

In terms of employment generation, smaller-scale systems are more effective than large-scale systems.

For marine aquaculture in particular:

Environmental regulations can greatly affect its development

Marine finfish present a good opportunity for development

Novel candidates could be sea cucumbers and sea urchins

Although in general potential sites for development are limited, the Central an northwest African coasts offer the greatest opportunities

Long-term solution to limited availability of sites could be improving the technology for pumping seawater ashore at relatively low cost

9.3 Recommendations for future strategy

Commercial and subsistence aquaculture systems should complement each other.

Clear cut policies for structured development (goals/plans/targets/resource allocation) should be defined.

Quality brood stock should be made available through applied research supported by government.

There should be an evolution towards decentralized seed supply with involvement of the private sector.

Research to improve feed quality and quantity should be supported by government for medium-to small-scale farmers.

Such research for large-scale operators should be the responsibility of the private sector.

For unformulated feed, priority should be given to the appropriate use of local materials.

Large-scale operators should be encouraged to support outreach schemes to help small-scale farmers in a win-win situation.

Public support should primarily be directed at smaller-scale enterprises.

Regional collaboration should be reinforced to provide technical training expertise and strengthening of existing institutions.

National and regional information networks should be set up.

Feasibility studies should be carried out on existing large-scale enterprises for convincing credit institutions of their economic viability.

Medium-to large-scale farmers should be required to submit returns.

The African Aquaculture Group should meet regularly.

10.1 Definition

A commercial aquaculture enterprise is an enterprise that seeks profit maximization, as opposed to small-scale integrated aquaculture where the goal is generally utility maximization.

10.2 Benefits and advantages

Commercial aquaculture generates its own revenues → no reliance on public funds.

Commercial entrepreneurs take risks (small-scale farmers usually don't).

The cost of technology development is borne by the entrepreneurs and not by governments.

Commercial aquaculture generates well-paying employment.

Commercial aquaculture generates income for local communities → it increases their purchasing power, and hence contributes to food security.

Commercial aquaculture can be a source of hard currency (earnings if product is exported, savings in the case of import-substitution).

It increases government revenues (tax collection)→ economic growth.

Can help small-scale farmers with similar objectives to overcome their seed, feed, and marketing problems.

10.3 Disadvantages and costs

Commercial aquaculture may not be sustainable if:

It leads to equity (income distribution) problems.

Foreigners dominate the industry

It leads to environmental damage.

Can hurt small farmers with similar objectives if appropriate policies are not in place to protect them from competition.

10.4 Sustainability criteria

Adequate level of return.

Stable level of return and minimum risk:

Stable physical inputs and outputs

Stable input and output prices

Social and cultural acceptance.

Internalization of externalities (by producers)

10.5 Suitable factors

Biotechnical factors (site, feed, seed, etc.)

Financial factors (equity or credit)

Micro-economic factors:

Must be profitable

Existence of a price and income elastic demand

Economies of scale

Suitable macro-economic policies

Exchange rate and inflation policies

Tax policies (corporate)

Good governance

Political stability

Low level of corruption

Suitable legal framework (property rights)

Suitable domestic and/or international marketing conditions:

Trade policies

Transportation

Competitive advantage

Quality control

Debt-equity swap (guaranteed profit repatriation)

Possibility of integration of feed-fish production

Vertical

Horizontal

10.6 Conclusion

In some African countries, commercial and small-scale aquaculture can be complementary activities in improving food security and alleviating poverty.

5 Submitted by N. Hishamunda and N. Ridler.

Establish national and regional information networks.

Organize annual meeting of African Aquaculture Group.

Initiate national and regional research programmes on brood stock management.

Privatize seed supply for medium to large-scale enterprises.

Initiate national and regional research programmes on feed quality, involving government (medium-to small-scale farms) and private sector (large-scale farms).

Organize a regional feasibility study of the economic viability of large-scale enterprises to facilitate credit.

Develop a national outreach credit scheme for commercial enterprises.

Organize regional specialized training courses for commercial entrepreneurs.

Develop aquaculture development plan on basis of clear cut policies: goals, targets, data collection, resource allocation and evaluations.

The strategies presented in the preceding sections for small-scale and larger systems have been merged and fixed to a recommended time-line. Items indicated for immediate implementation are those that it is assumed can be done with available resources and within the mandate of practitioners similar to those present (e.g. extensionists, directors and deputy directors, researchers and educators) without the necessity for higher-level approval.

Items planned to take place within one year would require some additional resources as well as approval from high level decision-makers. Subsequently, the longer the timeframe the more resources required and/or the more modifications to current policies or modus operandi.

Box 2. Strategy implementation schedule

| IMMEDIATELY |

|

| WITHIN 1 YEAR |

|

| WITHIN 2 YEARS |

|

| WITHIN 3 YEARS |

|

| WITHIN 5 YEARS |

|