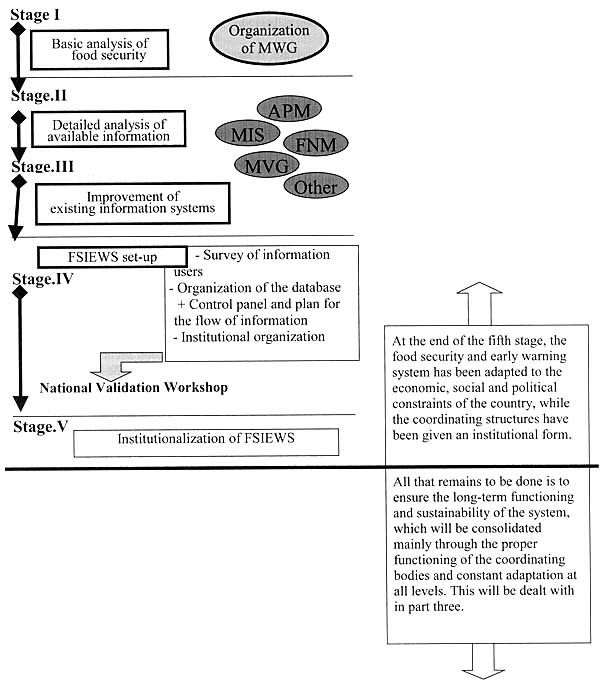

The institutionalization of the system takes place in two main phases:

The second phase deals with "running in" the system to a stage where it is operating smoothly and is sustainable.

Based on the experience of existing FSIEWS, the duration of each stage can be estimated albeit approximately:

It is not necessary, however, to wait four years before the FSIEWS is operational. It should be providing some services from year one (services such as the bulletin, very brief initially, should become ever more comprehensive, as indeed will the database, etc.)

As was mentioned above (Part Two, Chapter IV, Section 4), the FSIEWS should be attached to a National Food Security Committee (NFSC), integrating, at decision-making levels, representatives of the main technical organizations responsible for the national availability of food, the stability of supplies, access for all to these supplies and the biological utilization of these foods. The system also requires a decentralized form of the national committee, called in this handbook Provincial Food Security Committees (PFSC).

Some countries have adopted different food security information systems, distinct from the government and generally not linked to a national committee. These information systems have mainly been organized by donors, who also supervise them. They are wholly or partially sustained by direct funding. Such structures would appear to be unreliable in the long-term, since they are very often out of all proportion to the country's resources and are, moreover, neither integrated into the national structures nor linked to a National Assembly or other food security decision-making body. Therefore they can only function insofar as the donor pays the costs and supervises their activities and results.

There should be a two-way relationship between the FSIEWS and the NFSC. The FSIEWS first of all assists the NFSC in its decision-making role, providing it with the information to enable it to make decisions. It may then promote the NFSC at national level in its role as a national disseminator of food security information. In the other direction, the NFSC (which counts a number of ministers and other policy-makers among its members) helps the FSIEWS to obtain in good time the necessary information from the providers who would otherwise delay in providing them with it, and puts pressure on the FSIEWS to produce the data and analyses in good time while maintaining the required quality. The NFSC facilitates the work of the FSIEWS (by anticipating bottlenecks) but it also exerts pressure on it (by forcing it to play its early-warning role).

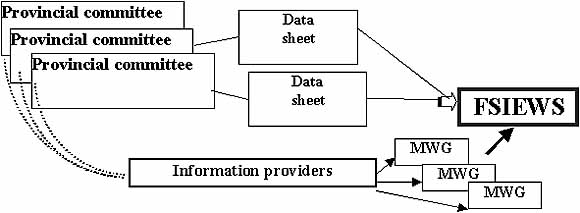

The FSIEWS' relations with the provincial committees are of a different order. Provincial committees are both providers and recipients of information. They supply both quantitative data, which is checked against data provided by government organizations and by the MWGs, and qualitative data (assessment of changes in the situation of vulnerable groups, likelihood of a crisis arising), which cannot be considered statistical data, but rather are indirect indicators of the changing situation. Provincial committees are also the only group in the system to transmit regular data on monitoring food aid in the field. In this respect, they therefore have a special relationship with the FSIEWS. For its part, the FSIEWS promotes the role of provincial committees in coordinating and monitoring food security activities and gives them a voice within the NFSC.

As the FSIEWS and provincial committees are set up, there should be no doubt at all that if the system is to be sustainable, it must be able to evolve. The composition of the national and provincial committees should be reviewed as circumstances change. For example, when disasters occur representatives from the army, the police, the fire brigade and civil defence should be integrated into the committees as they often play a major role in such circumstances.

The data sheets of the provincial committees should of course be constantly adapted, both to improve their accuracy, in terms of a better local approach to problems, and to vary their technical content as food criteria, social or economic problems, population shifts, etc. change and evolve.

The need to organize multidisciplinary working groups in each key area of food security has already been discussed in Part Two, Chapter I, Section 1.5. The original functions of the MWGs, forming the institutional basis on which to define and set up a FSIEWS, should evolve as the system is run in. Routine should be avoided at all costs in these structures: interest levels among participants have to be maintained and the tendency to hand over tasks to lower grades, who may be asked to substitute for their superiors at MWG meetings, avoided.

To avoid these risks each MWG should develop its own stimulating environment by taking on more responsibilities in preparing articles for the press and other media, and making sure there is enough happening at technical and staff levels to keep members interested. Therefore active participation in the MWG should be emphasized:

Right from the first stages in setting up the system, each and every person should know what his/her place in the system is, and how the system might evolve in line with changing national food security problems and national institutional changes.

It should not normally be necessary to impose a formal structure on the exchange of information and the flow of data, but experience shows that where personal contacts are essential in obtaining information in the set-up period, more formal agreement protocols are often needed in the long-term.

If the information providers work under the auspices of a ministry, a project or an NGO represented in the NFSC, it may be useful and effective to have the document initialled by the minister, or person in charge of the NFSC member organization.

The advantages of making these protocols legally binding should be seriously discussed in each country planning to set up a FSIEWS. It should not, however, be forgotten that the contents of the database and the FSIEWS management system are destined to evolve over time as they will have to constantly adapt to the changing economic situation and consequently the protocols will also have to be periodically amended.

The first steps to implementing the database and control panel should be based on the list of indicators and management methods approved during the national validation workshop. The bulletin, which is the organ of communication between the FSIEWS, information providers and recipients (or "customers", who may also be providers as described above), should include an article explaining the system status to everyone. Such an article, perhaps called "FSIEWS News", should give information on the work of the system as a whole: NFSC meetings, the work of the MWGs, staff training courses, news from regional monitoring stations, etc. It should also update readers on the latest changes or adaptations to the system.

Any proposed changes to the list of indicators, and other information regarding the database or control panel should be discussed by the relevant MWG. Once the need for change has been agreed, its effect on the provincial committees' data sheets, periodicity of the data, and agreement protocols, etc. has to be clarified. A technical note explaining the pros and cons of the change should be submitted to the NFSC for a decision. The NFSC, acting as a board of directors for the FSIEWS, has the final say on any changes. The approved changes should be implemented so that new information can be gathered with whatever regularity has been decided on, but also so that historic data on this information can, if possible, be compiled. A note in the bulletin will explain this change to everyone.

It may also be necessary to alter the composition of the MWGs, to change some agreement protocols, modify the appearance and frequency of publication of the bulletin, set up a specific press campaign or a special training course. In these cases, too, the NFSC secretariat, jointly with the lead managers of the relevant MWG, should write a brief explanatory note that is then submitted for approval to the NFSC.

As mentioned above, all modifications to the system (and since it has been designed to evolve, there will be modifications) should be carefully analysed, the final decision resting with the NFSC. The implementation of the changes will be the responsibility of the NFSC secretariat, working closely with all the other components of the system (provincial committees, MWGs, etc.).

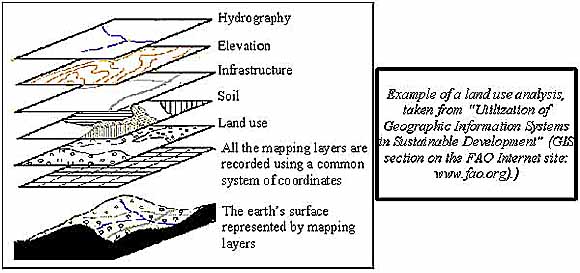

Geographic Information Systems (GIS) are advanced software tools for storing, analysing and publishing data. They can integrate spatial/geographic data with related non-geographic information stored in databases. The geographic data is generally organized in "layers", each one representing different physical characteristics (topography, roads, etc.), socio-economic characteristics (demography, income, etc.), agricultural characteristics, etc. of a given geographic area. One of its features is that several layers can be superimposed and new information gained by means of cross analysis. Of course the quality of the output generated by the GIS depends on the quality of the initial data supplied and the analytical skills of whoever is using it.

GIS have become very popular in recent years, having proved their worth in managing, analysing and illustrating a wealth of information about a country. Nevertheless their application in services in developing countries is still limited by lack of technical resources and suitable training. On the other hand. The use of GIS must be underpinned by information that is consistent and reliable if the spatial visualization of the data is to bring additional advantages to decision-making.

To make efficient use of a GIS in the framework of a FSIEWS, it is necessary to:

FIVIMS is a global information system on vulnerability and food security59 that stresses the need to map food insecurity and vulnerability to gain a better understanding of how these situations evolve and a better analysis of the different factors involved. It was set up in response to requests by participants at the World Food Summit (November 1996) for concrete action (therefore well documented) to be taken to reduce the number of undernourished by half by 2015. FIVIMS therefore focuses on the need to map the changes in this area.

FAO, in cooperation with the other members involved (IFAD, UNICEF, HCR, GTZ, UNDP, USAID, etc.), was therefore asked to develop simple mechanisms for effective mapping and, above all, comparison at a global level. The GIEWS60 already has an efficient software system, and is currently developing a system of on-line maps to be made available on the Internet.

FAO's World Agricultural Information Centre (WAICENT) has developed a Key Indicator Mapping System (KIMS) the aim of which is to share mapping information for key indicators and related data. Designed with the needs of the national and international partners of FIVIMS in mind, KIMS is a presentation and mapping tool for the main indicators of food insecurity and vulnerability. Its simple copy and paste options allow maps, spreadsheets, diagrams and meta-data to be widely used and disseminated, as well as allowing comparison of food security and vulnerability indicators and other data concerning food security61.

VAM and GIEWS also have specific software with which FSIEWS software should be compatible to avoid duplication of data.

As mentioned above (Part Two, Chapter IV, Section 4.1), the main roles of the NFSC secretariat are the following:

The secretariat of the NFSC should act as the executive organ of the NFSC. Although the number of managers in the secretariat is very small (two or three people), they can call on their counterparts at national (MWGs) and regional (regional committees or monitoring stations) levels.

As the FSIEWS gradually evolves, the precise role of the NFSC secretariat and its relations with the different participants in the system should become clearer. The long-term risk, already mentioned above, is that the NFSC secretariat (and therefore the FSIEWS, which is a component of it) may shift away from its primary responsibilities, either because its members see themselves as "information managers" (forgetting that they are just a cog in a system that includes information providers and the NFSC) or because one of the administrative bodies (or a donor) takes control. The essential point to remember is that information is the key to future development. There will always be some, driven by personal, political or other ambitions, who will exert whatever pressure they can either from within or outside the secretariat to control it.

As an interdisciplinary committee for the exchange of information and decision-making, the NFSC should direct, supervise and support its secretariat attentively: without such vigilance the system risks becoming a tinderbox.

In an age when information is omnipresent, when processing and disseminating techniques are ever more numerous but also increasingly simple to use, information and communication activities relating to food security should make maximum use of such resources to produce a message that is clear and useful to its audience. It should not be forgotten that more traditional means of communication (notice boards, rural radio, public meetings, etc.) are still valid and useful ways of informing traditional societies. The "market place" can often be an ideal site for exchanging information, something that politicians have long understood.

Current projects in developing countries make use of four main dissemination methods:

There are however many other methods used by the FSIEWS:

In order to find a way through this maze of possibilities, the NFSC secretariat should ask the following questions:

It should be noted that although these questions will have been asked and provisionally resolved at the national workshop to approve the FSIEWS, they should be raised regularly by the NFSC secretariat as part of the on-going adaptation of the system so that it can more closely respond to requirements and available options.

The NFSC really does have to be in charge of the FSIEWS, and the FSIEWS, albeit playing a fundamental role, is an instrument of the NFSC. This principle cannot be repeated too often.

Therefore at regular intervals (e.g. twice a year) the NFSC should review the work of the FSIEWS and examine the following points:

At the end of the review, a clear summary of the decisions taken by the NFSC should be prepared and instructions accordingly given to the FSIEWS.

What should be avoided at all costs is that the FSIEWS receive orders from, or come under the influence of, bodies or people outside the NFSC. But, as mentioned above, the FSIEWS has to remain an executive instrument of the NFSC and should not act on its own initiative without having first discussed its plans with the NFSC and received its approval. No single member of the NFSC should be able to exert an influence on the information system. Complete transparency of the information used and processed by the FSIEWS is the only way to guarantee an efficient and sustainable system.

Mozambique is an interesting example of the rapid evolution of a poor country coming out of a crisis situation and moving towards a situation of sustainable development. The national authorities had to develop a food security information system to deal with this particular situation. The aims of the system should gradually progress from targeting emergency aid to supporting the marketing of food products and developing a new food security policy in a market development framework.

In spite of the change in the general aim, predicting food crises is still a priority area, especially given the frequency with which natural disasters occur in this country (floods, droughts, etc.). Unfortunately, the quantity and quality of available information in the different food security areas is poor. At provincial and national levels, in the public, private and voluntary sectors, there is, however, keen interest in setting up a network of information systems on food security and nutrition. FAO and the Commission of the European Community have therefore helped the country to set up the network of information systems presented below.

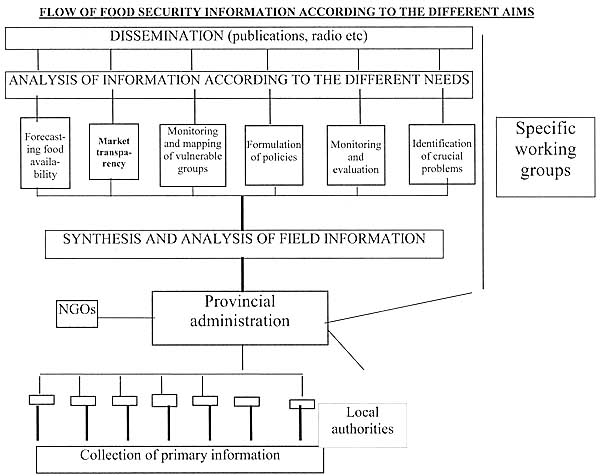

What is immediately apparent from the diagram is that much of the data analysis in Mozambique is done at provincial level (while in the standard FSIEWS system the work is shared between the provincial committees and the MWGs). On the other hand, the working groups do not focus exclusively on food security and development policy.

The reasons underpinning the organization of such a system are as follows:

59 See details in Part Three, Section Four.

60 See Part Three, Section Four.

61 See details on the FIVIMS web site: www.fivims.net

62 See Part Three, Section Four.

63 http://www.fivims.net/DEFAULT.htm

64 See Part Three, Section Five.

65 http://www.fao.org/WAICENT/faoinfo/economic/giews/english/giewse.htm