BUDAPEST, HUNGARY

6-10 MARCH 2001

1. INTRODUCTION

[1] The Meeting was convened to facilitate the development of seed policies and programmes for the region as part of the FAO strategy for implementing the recommendations of the Plan of Action of the World Food Summit, adopted in Rome in 1996, and the Global Plan of Action for the Conservation and Utilization of Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture, adopted in Leipzig, Germany, in 1996. The meeting, held in Budapest from 6-10 March 2001, was organized by the Agricultural Research Institute of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (HAS), Martonvasar, with technical and financial support from the Food and the Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO).

[2] Participation was broad, with official participants from 22 countries of the region (Albania, Armenia, Belarus, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Georgia, Hungary, Kazakhstan, Latvia, Lithuania, Moldova, Poland, Romania, Russian Federation, Slovakia, Slovenia, Turkey, Ukraine, Uzbekistan and Yugoslavia. Participants attended from international organizations, international agricultural research centres (IARCs), governmental organizations and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and public and private sector organizations involved in the seed industry. In addition, others attended the meeting either as observers or in a personal capacity.

[3] Dr Zoltan Bedo, Director-General of the Agricultural Research Institute of HAS, Martonvasar, welcomed the participants at the opening ceremony, attended also by senior government officials, representatives of the National Organizing Committee of the Meeting, representatives of aid agencies and eminent seed scientists. Opening addresses were presented by Dr Peter Szerdahelyi, Deputy Secretary of State in the Office of the Prime Minister of Hungary, and Mr Bertalan Szekely, Head of the Agricultural Division at the Ministry of Agriculture. A keynote address on behalf of FAO was delivered by Mr Mahmud Duwayri, Director, Plant Production and Protection Division (AGP) of FAO, and Mr Jaroslav Suchman, Head of the Subregional Office of FAO, delivered the FAO welcome address. The full texts of the speeches, where available, are presented in Appendix 3. The list of participants is provided as Appendix 2, and the Agenda as approved is given as Appendix 1.

1.2 Objective of the Meeting

[4] The broad objective of the meeting was to define policy guidelines for member countries, to strengthen intra-regional collaboration and national capacities required for crop germplasm maintenance and equitable sharing, varietal improvement, production, multiplication and supply systems for good quality seeds of varieties adapted to the agro-ecological conditions in the region.

[5] More particularly the Meeting was expected to:

- provide a comprehensive and coordinated assessment of seed sector activities at regional and national levels, building upon a regional seed assessment prepared by FAO;

- evaluate trends and requirements related to seed production in terms of different crops and varieties, infrastructure and capacity-building issues, and international arrangements governing seed movements in international trade;

- identify modalities for the development of seed policy frameworks in the countries, to facilitate technology transfer and international seed trade;

- identify priority needs for national, subregional, and regional projects and programmes in line with the Global Plan of Action, especially as it related to crop germplasm management and equitable sharing, to enhance unimpeded access of farmers to crop varieties suited to their agro-ecological and socio-economic conditions;

- strengthen linkages between genebanks, plant breeding organizations, seed producers, and small-scale seed production and distribution enterprises;

- consider appropriate measures and mechanisms to improve seed security at the national or regional levels and the capacity to respond to natural or man-made disasters in the region; and

- contribute to the elaboration of a global framework for seed policy and programme strategy.

2. THE MEETING

[6] To establish a framework for discussion at the Meeting, a reference document was prepared by FAO, entitled Seed Production and Improvement Assessment for the Central and Eastern European Countries (CEEC), Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) and other Countries in Transition (CT). This reference document was supplemented by seven technical thematic papers on seed and genetic resource issues relevant to the region. The Meeting was conducted in English, Russian and Hungarian, with simultaneous interpretation. Brief summaries of the papers presented at the meeting and highlights of the discussions that followed each presentation are presented in sections 2.1 to 2.11 below. The full texts of these papers are provided as Appendixes 5-7.

2.1 Reference Document: Seed production and improvement: Assessment for Central and Eastern European Countries (CEEC), Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) and other Countries in Transition (CT)

[7] The reference document (Appendix 5 to this report) briefly reviewed the agro-ecological conditions, socio-economic settings, and the impact of transition from a central to a market economy on the overall agricultural development of the countries of the region. It highlighted that resources, technology and appropriate facilitative policies required for the transition to market economy have led to shortages in supply of improved seed for major crops. This shortage constituted one of the important contributing factors in the unsatisfactory situation in agricultural development in many countries of the region.

[8] The agricultural sector was of vital importance for the region, and was undergoing a process of transition to a market economy, with substantial changes in the social, legal, structural, productive and supply framework, reflecting similar changes in all other sectors of the economy. These changes have been accompanied by a decline in agricultural production in most countries, and have also affected the national seed supply sectors of the region. The region had to face problems of food insecurity, and some countries required food aid for Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) and for refugees.

[9] Considering the relatively low demographic pressure projections for the future, the presence of areas with favourable climates, and other positive factors, such as a very wide formal seed supply sector, it should be possible to overcome problems of food insecurity in the region as a whole, and even to use this region to provide food to other food-deficient regions. Opportunities had therefore to be created to attain these outcomes.

[10] In order to address the main constraints identified as affecting the development of national and regional seed supplies, the region required integrated efforts by all national and international stakeholders and institutions involved in seed supply and plant genetic resource management. On practical issues, lessons learned by some countries could be shared with other countries, such as how to advance with the transition, or how to recognize the most immediate needs of farmers. Appropriate policies should also be established, at various levels, in order to facilitate seed investment and development in the region

[11] In the ensuing discussion participants made the following points:

(i) Transition from central control to a market economy had led to an increase in on-farm seed saving and a drop in the demand for certified seed. The trend might increase before stabilizing. However, the appropriate balance between formal and informal seed sectors activities would vary from country to country and would be determined by the crop species - hybrid versus self-pollinated. Hybrid seed, such as maize, would probably be certified seed from the formal sector, while on-farm seed saving would be more prevalent for self-pollinated crops.

(ii) As an interim measure, improved quality farm-saved seed should be encouraged until adequate expertise had been gained by farmers to become local seed entrepreneurs for local seed production and distribution.

(iii) Farmers first selected improved varieties; hence the informal sector was very important. To this end, local varieties should be improved, as this could be a way of reducing the cost of farmer’s inputs.

(iv) There was a changing perception of seed use. The level of seed replacement in the former system had been unnaturally high due to central planning and state control, whereby all farms received certified seed from the government.

(v) It was difficult to set up private breeding programmes because this required a lot of funds. For this reason, it was important that state breeding programmes continued to be supported.

(vi) In response to a suggestion that it was difficult to get access to public and private germplasm lines for private breeding, it was pointed out that in France there was easy access to both public and private material, especially for the purpose of plant breeding. However, the official view in this region might be that private breeding should not receive government assistance. There were considerable differences between countries of Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia. In order to sell seed in the European Union, the countries in transition would need to provide certified seed to conform to the needs of that market.

2.2 Thematic Paper 1: Management, conservation and utilization of plant genetic diversity in CEEC, CIS and CT - Sergey M. Alexanian.

[12] The thematic paper gave a comprehensive overview of the current situation in the field of plant genetic resource (PGR) collections, their maintenance and use in the countries of the region. It concluded that, in all groups of countries, the legislation concerning germplasm of cultivated crops and their wild relatives either has not been worked out at all, or was still being developed. At the same time, nearly all countries had a Red Book of their own, which listed rare and endangered plant species placed under governmental protection. Some countries had computerized databases for their ex situ collections, developed using international lists of descriptors (e.g. Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Russia, Slovakia and Uzbekistan). In countries such as Georgia, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, Croatia and Macedonia (FYR), databases either did not exist at all, or were being created. Practically all the countries were experiencing shortage of funds for PGR activities, even though the importance of the problem had been realized at government level. The involvement of all the countries in activities of regional programmes such as ECP/GR and WANA/CACNET was a factor helping to achieve success in joint activities at the regional and global level.

[13] In the ensuing discussion, participants made the following points:

(i) Caucasus and Central Asia had been put in the same group, despite great ecological differences between them, because the conditions were comparable in many ways, especially the fact that they were all part of the former Soviet Union.

(ii) Most countries in the region had ratified the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and the flow of genetic resources was satisfactory, both with Western Europe and eastern countries. However, the first stage of collaboration was to set up the mechanisms of exchange at national level, as there was no clearly defined responsibility concerning to whom to turn should one want genetic resources material.

(iii) As regards legislation, the 1992 CBD had been signed by the Russian Federation, but not by other CIS countries. A lack of legislation governing biological diversity currently constituted an obstacle in the region.

2.3 Thematic Paper 2: Agricultural research and technology transfer to rural communities in CEEC, CIS and CT - Karol W. Duczmal

[14] The paper dealt with the problems faced by agricultural research and extension in the transition period in the countries of the region. National Agricultural Research Systems (NARS) in Countries in Transition (CT) were formerly highly organized, fully funded and overcapitalized. The CEEC and newly independent countries of the former Soviet Union (FSU) inherited from the FSU system a number of agricultural research institutions designed to serve a country with a command economy. The CEEC and the new Republics were then left with the daunting task of creating effective and sustainable systems to serve national needs. For dealing with agricultural research institutions, the dominant strategy in many countries was one that in effect maintained the existing institutions, i.e. system preservation. This strategy derived from forces in the existing scientific communities seeking to maintain the status quo. However, due to lack of finance, the probable outcome of the strategy would be mainly the downsizing of existing research institutions. This seemed to be happening, despite the very strong desire to optimize NARS by both scientists and government agencies. However, the importance of a scientific and systematic approach to this optimization was underestimated. The future development of these research systems would largely depend on the political will of the NARS leadership to take bold steps for reform, developing a sound strategy for this process. This strategy had to take into account future demand for agricultural research, as reflected in emerging local and international markets, and be conditioned by the optimal utilization of the physical resources available.

2.4 Thematic Paper 3: Harmonization of seed legislation and regulation in CEEC, CIS and CT - D. Gisselquist

[15] Harmonization to world best practice would provide the foundation for a modern seed industry. Many regulatory features were crucial for the development of a market-oriented seed industry, including, for example, easy entry for new companies and varieties, plant variety protection, and science-based phytosanitary controls.

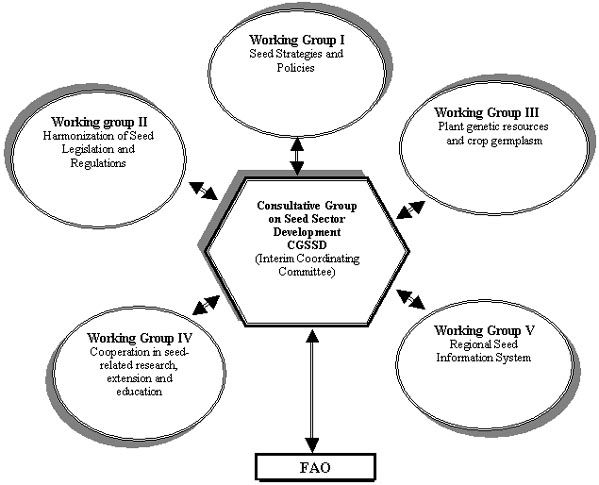

[16] At the same time, regional harmonization was a concept that covered many options. In most discussions, the objective of regional harmonization has been to create a larger regional seed market in place of multiple smaller national markets.

[17] The options for harmonization in the region could be summarized and assessed as:

(i) For the 10 countries in Central Europe that planned to join the EU in the near to intermediate future, harmonization for all intents and purposes meant opening to the EU and to the world seed industry and markets.

(ii) For smaller countries in the region, harmonizing to world best practice (including liberalization) would give small countries access to seeds from the EU and other large and developed seed markets. Without liberalization, harmonization to create small but closed regional markets offered little gain.

(iii) For large countries in the region - principally Russia and Ukraine - opening to western companies and markets would be to maintain regional leadership.

[18] Although harmonization to world best practice was the most important task, within subregions there were opportunities to cut costs and to improve efficiency through regional cooperation, particularly in the areas of Plant Variety Protection (PVP) and phytosanitary controls.

[19] In the ensuing discussion, participants made the following points:

(i) The question relating to certification should be whether it should be voluntary or compulsory. In the USA, and also in Germany, certification was a state function, not a central government function. In the EU, 40 or 50 species require certification, while the majority of vegetable crops did not. Private companies sold most seed and were responsible for their own quality assurance. The farmers trusted them and did not wish to pay more for official certification.

(ii) Unilateral acceptance of the EU variety list was not a good solution because it put plant breeders from CEEC countries at a disadvantage compared to breeders from the EU. A more acceptable solution would be bilateral acceptance of variety lists.

(iii) The EU system was not universal and the registration systems were different in each member country.

(iv) Harmonization should be seen as a two-step procedure - harmonization at regional level first, and then harmonization among regions. Step 1 was particularly important for countries wishing to enter the EU. Harmonization might be difficult on some issues (e.g. certification, genetically modified organisms (GMOs)). Compatibility of regulations was probably a more reasonable objective than complete harmonization.

(v) The International Seed Trade Federation (FIS) also contributed to harmonization through publication of the International Seed Trade Rules that applied to commercial contracts among seed companies.

(vi) Small- and medium-sized seed companies could be made more viable in the market through affiliation or linkage with international breeding companies. Many international companies looked for foreign companies to act as their representatives, and so cooperation could evolve. In Georgia, for instance, 12 multinational seed companies were now operating.

(vii) The possible dangers of increasingly open crop registration were noted, leading to farmers being unable to differentiate between the best varieties and the best-advertised varieties. It was thought that farmers would soon overcome their initial confusion and eventually call upon their past experiences to make good choices.

(viii) In view of the relationship between level of enlightenment and ability to make the right decisions on varieties available in the market, farmers should be given every help and advice to learn new technologies so they can make their own choice of varieties, based on knowledge, not just company advertising.

(ix) In the EU there was an EU list of all the varieties registered in all the countries, but there were also recommended lists for individual countries or regions of countries. The varieties on these lists were generally those most frequently grown in that region. This gives better regulation of distribution, so it was a good solution. Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia had not accepted the EU regulations because they were not open in both directions. Varieties that did not satisfy UPOV regulations should not be allowed into the EU, but many countries in the region were members of UPOV, so their varieties should be allowed free entry.

(x) Non-EU countries had to fulfil stringent EU conditions to be admitted, but they were asked to accept EU varieties without any restriction. Best-practice harmonization was a problem. OECD certification provided a seed passport for non-EU countries to enter the EU more easily. OECD conditions were the same for both sides and so a step towards a solution.

(xi) With respect to making official variety recommendations to farmers, a selective approach might be adopted. For widely grown staple crops, more official advice might be required. For some crops, such as vegetables, farmers should be allowed to make their own decisions and choose the variety that would best fit their conditions. In Turkey, a minimal requirement for vegetable variety registration had been followed for the previous seven years and it had worked well. There had been little deceptive advertising or misguiding of farmers. In almost all cases, the farmers were making correct decisions in this respect.

(xii) Registration in the EU is open to foreign breeders. Many varieties from CEEC had been registered.

(xiii) To maintain variety diversity, borders would have to be opened with minimum restrictive regulation. Small companies in CEEC have had good results, but they needed partnerships with foreign breeders. As an example, after the Second World War, USA cultivars of maize were grown in France. Then national institutes began breeding, and when they developed new inbred lines, they sold them to private companies, with the result that there were now large companies breeding maize in France.

(xiv) Poland was totally opened to foreign varieties, with free flow of varieties from the common catalogue. Nevertheless, 60-70% of the varieties grown in each country came from the national breeding programmes. In Poland, the new post-registration system filtered the best varieties from any country for cultivation in Poland. There was strong environmental selection. Listing of varieties was the first step. Any foreign breeder could come and start variety testing. Most of the best varieties in the EU were also present in Eastern Europe. This was the direction to go in, building on the positive results achieved thus far, and it would be foolish to turn back.

(xv) The EU list of varieties was very long. In order to keep their customers, seed companies would ensure that only suitable varieties were advertised. The contracts between seed traders and farmers included correct information on the quality of the variety. If this information were not correct, the company could be sued. Nevertheless, there could be initial problems in the countries in the region, and legal remedies should be avoided if possible.

(xvi) National boundaries were not a good basis for determining the use of crop varieties, since farmers could easily see what varieties grew best in their conditions and would want to use the most suitable variety, regardless of origin.

2.5 Thematic Paper 4: The role of national seed policies in re-structuring the seed sector in CEEC, CIS and CT - Michael Turner

[20] In the centrally planned economies of the past, a policy was not required because the government simply organized the seed supply as part of the overall planning process. With economic liberalization, other suppliers were expected to enter the seed market to provide choice for farmers. The task of government was now to create an enabling environment for that to take place, and policy played a key role in this. A seed policy was a declaration by government of the way that they wished the seed sector to develop. It provided a guideline for developing the seed sector and should define the responsibilities of the various participants. It should be published as a document since that provides greater confidence and transparency; it would then also be more difficult for the government to deviate from the policy for reasons of short-term convenience.

[21] Policy was not the same as legislation, but they should of course be consistent.

[22] The seed policy should be monitored and managed to make sure that it is achieving the desired objective. It should be stable, but still responsive to changing needs as the seed sector evolved - a difficult balance to achieve. To achieve this goal there should be a National Seed Council or similar body, on which all parties were represented and which would report directly to the Minister of Agriculture. The private sector was best represented through a National Seed Association, which would represent the interests of its members in the National Seed Council.

[23] Among the key issues that should be addressed by the seed policy were: encouraging new entrants to the seed sector by removing barriers and providing incentives; ensuring open access to facilities and services, such as quality control; providing access to public-sector varieties, for example through licensing arrangements; liberalizing variety testing, listing and introduction to provide greater choice; and removing production subsidies that might distort the market and discriminate against private companies.

[24] Although policies were designed to meet national needs, there were also strong regional or international dimensions. For example, the policy should encourage foreign participation or investment in the seed sector, it should encourage participation in international organizations, promote harmonization of regulatory procedures and the development of commercial links. The policies of countries should also be formulated along similar lines to facilitate this process of commercial and regulatory convergence. This current meeting, and the activities that could flow from it, might play a key role in this process.

[25] The overall challenge facing countries in the region was to create a new, diverse, seed sector equipped to meet the needs of a changing agricultural industry on a financially viable and secure basis.

[26] In the ensuing discussion, participants made the following points:

(i) Ten years ago, Uzbekistan produced 6 million tons of cotton, which was the main crop. No wheat was produced in the country at all. The country purchased 4 million tons of wheat from Russia and Canada. After independence, the situation changed, and wheat is now grown on 1 million ha. The yield of 4 million tons is enough to supply the needs of the 23 million population. There have also been losses. Previously, alfalfa seed was produced on a large scale and was traded for breeding cattle from the Baltic States. Now no alfalfa seed is produced.

(ii) Since the break up of the former Soviet Union, the independent countries have undergone a very rapid transition, and the new borders between the countries were very unnatural. For instance, in Tajikistan, there were frequent droughts and food shortages, and to solve the problem, seed could be obtained from Kazakhstan, because they grew the same varieties. In Soviet times that was not a problem, but, since independence, the new international boundaries in the region can make this movement of seed much more difficult.

(iii) Turkey was a very interesting example, because they were among the first to make major policy changes and to achieve good results. The country was also interesting because the situation was very mixed - they still had state farms, for instance, and in fact the biggest state farm in the world was to be found in Turkey. The country was still undergoing changes in its seed sector.

(iv) The privatization policy of the seed sector in Turkey started in 1985 and led to a general improvement in crop production. The private sector had the opportunity to develop and to provide better quality seeds of a larger number of varieties, with surplus for exports at the present time. Now, no one resisted privatization and around 120 varieties were now being brought into Turkey from all over the world. In spite of the high cost of imported tomato seed, still farmers rushed to buy it. There had been real increases in the yields of maize, sunflower and potatoes. The most important thing was to use the best varieties, even if they were developed elsewhere.

2.6 Thematic Paper 5: The role of private companies in development of seed production and supply systems: The Hungarian experience - Janos Turi

[27] The history of the Hungarian seed sector and the course of seed privatization demonstrated that traditions and participation in international seed associations were of decisive importance. It was thus important to revive traditions, to renew and strengthen international contacts and to accede to international associations and agreements.

[28] It was essential for associations functioning within the seed sector to operate efficiently and to develop into strong civil organizations capable of protecting their interests.

[29] The fact had to be recognized that a fundamental criterion for the consolidation and development of agricultural production was to subsidize the use of biological reproductive materials of guaranteed quality, especially that of certified, dressed seed in field crop production.

[30] Within the privatization of agriculture, that of the seed sector was of special significance. It was essential that the existing plant breeding institutes and varieties remain in state ownership, because these had enormous value, which it would only be possible to assess objectively at a later date. Economic transformation would be a protracted process, in the course of which domestic breeding institutes and varieties should be given as much support as possible. It had to be accepted that, in a market economy, business considerations had priority, so specialists in the seed sector should be trained to understand how the market works. One of the most important tasks was to create a balance between local opportunities and the effects of globalization. In the privatization of agriculture, the whole of the production chain had to be taken into consideration. Were only food privatized, seed producers and farmers in general would be forced into an intolerable situation. Only a complete agricultural production chain would be capable of ploughing back capital into breeding and research in order to ensure its own future development.

[31] It had to be emphasized that specialists who felt a responsibility for the fate of the seed sector could and would find a solution for the privatization of the sector and for its day-to-day problems. Both agricultural history and daily experience made it clear that this would only be possible if these specialists considered the region as a whole and aimed to join the mainstream of the world seed trade.

[32] In the ensuing discussion, participants made the following points:

(i) The subsidies provided to seed producers in Hungary were linked to basic biological materials, so seed and breeding animals were subsidized. The funds available were very modest and the subsidies took the form of low-interest loans. The assistance given in this way to seed producers was indirect. Farmers could apply for low-interest loans if they could prove that they had sown at least 40% of their land with certified seed (this figure was obviously 100% for hybrid crops). If farmers bought more certified seed, the local breeding companies would thus have more income. These loans were available not only for seed, but also for fertilizer, plant protection agents, etc. Exports as such were not subsidized.

(ii) Many people thought that the seed sector should support itself from its profits, but this was a shortsighted policy. The performance level of the seed sector affected the whole of agriculture. History had shown that whenever the Hungarian government supported the biological bases of agriculture, it led to an upswing in agriculture.

(iii) Hybrid seed came mostly from multinationals. The economic reforms in 1968 involved an open policy, as a result of which the multinationals appeared in Hungary in 1975, and by 1990 Pioneer had almost 90% of the market. This proportion had since dropped, due to the presence of other firms, but Hungarian-bred hybrid maize still had only 30% of the market. This was a promising result, but progress was slow. The foreign firms were given a market advantage in earlier years, so it was difficult for local firms to catch up. The effects of globalization were felt all over the world, but the government could do much to decide the extent to which they would be felt.

(iv) In the 1920s and 1930s, Hungary had a large export of seeds of minor crops, but this had dropped to only a few tons. Such crops required high investments, which would only be returned in the long term, so private firms did not have enough capital and needed support from the state. In the case of cereals, Hungarian seed had maintained its position in the Hungarian market.

(v) Most private seed companies in Hungary were representatives of multinationals, or produced seed for them on contract, but there were a few dozen purely Hungarian companies, which dealt not only with breeding, but also with processing, etc. These companies bred small crops, where they could do what larger companies could not do. One example of this was spice paprika, which was a Hungarian speciality. Another was oil linseed, which had been bred so successfully that most of the varieties grown worldwide were Hungarian.

(vi) Hungary’s policy on GMOs was basically the same as that of the EU. There was no ban, but all GMO varieties had to undergo strict testing. Within a few years, the first varieties might enter general cultivation. In Western Europe, there was considerable fear of GMOs, so the fact that no GMOs were grown as yet in Hungary could be a marketing advantage.

(vii) There was no special programme for the support of private breeding companies. Funds were restricted and basically breeding institutes had to generate their own research and development funds. The Seed Product Council was concerned that more Hungarian-bred seed should be sown, as this would provide more income for breeding institutes and contract growers. In 2001, a regulation was expected to be passed giving 50% government support to the costs of variety testing for Hungarian varieties.

(viii) It might be useful to document the story of the Seed Product Council as an example for other countries. The Seed Product Council was set up in 1993 after considerable debate about the need for it. Seed breeders, growers and traders felt that they needed a separate organization, as seed was a very special product, of decisive importance for agriculture. It was felt that it was not sufficiently represented by the existing Product Councils for Cereals and Legumes. Political and economic changes were rapid and democratic in Hungary, and it proved possible to convince the government of the need for the Council. Currently, there were nearly 1 000 members. The views expressed by the Council were gradually gaining more and more weight. One example was that subsidies were now linked to the use of certified seed.

(ix) In response to a request for more information about the Bishkek Agreement, mentioned in the presentation, it was noted that, in 1996, Hungary was exporting considerable quantities of seed to CIS countries, but without knowing what quantity of seed would be required the following year, so seed was produced at great risk. Long-term commitments were needed, so Hungary initiated the meeting in Bishkek to try to revive the cooperation previously provided by COMECON, which had advantages in providing stable markets. The agreement was signed by over a dozen countries, but due to the bad economic situation in Russia in 1996, payment difficulties arose. The previous buyers wanted to buy seed, but Hungary was unable to supply them on credit. Private firms could perhaps have decided to take the risk, but because state companies were involved, the authorization of the government would have been required. This was not forthcoming because Hungary was also going through a difficult period, with various restrictions and a drop in the standard of living. As a result, the Bishkek Agreement did not work, but such cooperation was definitely needed. Agricultural development started with seed and if the seed trade worked well it would have a positive effect on the whole of agriculture.

2.7 Thematic Paper 6: Biotechnology - a modern tool for improvement of food production - Patrick Heffer

[33] Plant biotechnology had the potential to be a key tool to achieve sustainable agriculture, through improvement of food production in terms of quantity, quality and safety, while preserving the environment. However, plant biotechnology was not sufficient in itself to achieve this challenge. For instance, biotechnological inventions had no value if not associated with an improved and adapted genetic background. Similarly, if seed distribution networks were not effective, seeds carrying biotechnological inventions would not reach farmers. Therefore, plant biotechnology should be considered in the framework of the agricultural sector at large, taking into account scientific, technical, regulatory, socio-economic and political evolutions.

[34] As far as plant biotechnology was concerned, FAO had a central role to play in serving as a forum to negotiate international instruments that would ensure safety and facilitate international trade, promoting collaborative work and technology transfer, and providing technical assistance and policy advice. With respect to FAO’s mandate, the Organization could ensure that all parties take measures that would ensure that the less advanced countries and resource-poor farmers also benefit from plant biotechnology. This should be done in close collaboration with other international organizations tackling agri-biotechnology-related issues, to optimize the efforts of all those who shared a common objective.

[35] In the ensuing discussion, participants made the following points:

(i) ISAAA (www.isaaa.org) publishes an annual report on the status of transgenic crops and this indicated that transgenic crop acreage had increased to 44.2 million ha in 2000 from 39.9 million ha in 1999. This change depended on the country (increase in Argentina, USA, China, South Africa and Australia; decrease in Canada) and the crop (increase in herbicide-tolerant soybean, maize and cotton, and Bt cotton; decrease in Bt maize and herbicide-tolerant rapeseed). The decrease in Bt maize was due to lower pressure of European corn borer, thanks to the use of Bt genes. The decrease in herbicide-tolerant rapeseed was due to the market. Other transgenic crops continued to increase as a result of their comparative agronomic advantages.

2.8 Thematic Paper 7: Regional cooperation in the seed sector of CEEC, CIS and CT - Zoltan Bedo

[36] The food security of the region was not satisfactory during the period of the socialist economy, although there were considerable differences within the region. The majority of the countries were net importers of food and agricultural products. During the transitional period, agricultural production declined even further year-on-year, and a system providing greater food security had still not developed in most countries in the region. This could be attributed to a number of factors, including the lack of cooperation in the region, which also had a negative effect on the seed sector.

[37] There has now been a move in the region to re-think national seed policies in the light of market-oriented economic principles and international legal norms. In the long term, harmonious relationships within the region would only be viable and mutually advantageous if the new national seed policies were all based on the same principles, including privatization of the seed sector, laws ensuring the operation of the seed sector and guaranteeing the protection of intellectual property rights, and internationally compatible quarantine and seed testing systems.

[38] Future cooperation had to conform to a market economy if the seed safety of the farmers were to really improve. It was recommended that regional coordination should be set up for the drafting of laws playing a key role in the national seed policy, so that these would promote the development of the seed sector and international cooperation. The coordinated cooperation of regional and national actors would help to provide greater security for local actors, as would an efficient strategy of partnership between private and public stakeholders. The preservation of East European germplasm and the coordination of research in this field were an urgent task. In most countries in the region, there was a need to define the future role of the informal seed sector. By setting up an East European database on the basis of national variety lists, it would be possible to decide which varieties of the strategically important plant species should be used as seed reserves in the event of natural catastrophes. The state reserves of individual governments or those of international seed companies could be designated for this purpose. The financing mechanism should be elaborated on an international scale in order to achieve maximum efficiency at the lowest possible cost.

[39] In the ensuing discussion, participants made the following points:

(i) The basis for national seed policy would be a set of legislation governing breeding and the seed sector. Russian laws were fully compatible with those of the EU. Russia had joined UPOV and done much to become a full member of OECD. Private breeding was now possible. There were a total of 225 institutes, 40 of which were also involved in seed trading. Steps were being taken towards privatization. Significant breeding and seed institutes had been established in various places, and in the previous five years, 700 foreign varieties had been introduced. Russia’s goal was to be an equal partner with the large seed companies. There was a great need for databases, which would have a positive influence on efforts to achieve food security.

(ii) The presenter was asked what concrete programmes were planned by FAO for countries in a poor economic situation, and was there any intention to make use of the genebank at the Vavilov institute, and if so what support would be provided? The response was that the Meeting should think of programmes to be created for this region to take advantage of the large genebank at the Vavilov institute. Also some assistance should be rendered for the maintenance of gene reserves at this institute.

(iii) The privatization of research institutes was now in progress in Russia, and new seed companies had also been established. Within the Agricultural Academy there were 43 breeding centres in the various climatic regions. The many regions had widely varying climates, so different varieties were required for each. At the beginning of perestroyka, state funding of breeding centres dropped by 80%. The majority of the breeding centres operated under the Agricultural Academy but were financially independent. So they have had to sell high quality seed to provide funding for their research. Some special institutes, like the sunflower institute, were 100% privately funded. This institute had an excellent breeding base and was producing modern hybrids. The Rossiskiya Semena Co. had subsidiaries in each region and produced seed on a cooperative basis. They had a number of patents and had bred around 50 varieties of vegetables, maize and other cereals. The Gavrish Co. was a private company working on a contractual basis. It was strong on breeding and seed sales of tomatoes and vegetables, and played a large role in the Russian market.

(iv) To prevent possible conflict between the challenge to liberalize entry of foreign varieties into Hungary and the efforts of local research institutes to make money from royalties, no distinction should be made between domestic and foreign varieties in variety trials. The fees and conditions should be the same for all. In some countries, the fee for variety trials was three times higher for foreign varieties. This was unreasonable - variety registration was for the benefit of farmers, not breeders. Nevertheless, a registration process was necessary, to determine which varieties were suitable for which ecological zones. For instance, in Hungary, royalties were introduced in the 1980s, but were a percentage fixed by the government and were the same for Hungarian and foreign varieties. In the early 1990s, the government let breeders decide on the percentage on a market basis. Now if the percentage were too high the farmers would not buy the seed of home varieties; were it too low there would be no income.

(v) In place of holding seed reserves, it would be better to rely on the OECD database to determine which varieties were required for each region. This database was available to all countries that were members of OECD. In many countries, especially Russia and the Ukraine, the local varieties were populations, not fixed varieties. The seed sector should be modernized without losing the advantage of populations.

(vi) During the war in Kosovo, seed supply suffered to a great extent. In Eastern Europe there were often floods and other natural catastrophes, after which good quality seed would not always be available. The problem was: How to finance and maintain carryover stocks? The OECD database might be useful. It was important to improve the quality of the seed sown. Populations did not satisfy Distinctness, Uniformity and Stability (DUS) requirements because they were not homogeneous, but they might be very useful in times of environmental stress.

(vii) The role of the informal seed sector varied from country to country. In some places, the formal sector was more important, in other places the informal sector was greater. If it could contribute to the development of agriculture, then use should be made of it.

3. RECOMMENDATIONS

[See Appendix 8 for a Russian translation of this section]

[40] It was proposed, and the Meeting agreed, to establish an Inter-Governmental Regional Consultative Group to coordinate all seed initiatives in the region, and it was requested that the Consultative Group be placed under the aegis of FAO.

[41] The Consultative Group would be open to all countries interested in the improvement and development of the seed sector and in plant genetic resources conservation and utilization in the region. This Consultative Group would facilitate exchanges amongst the existing cooperative programmes in the region, particularly in seed and PGR-related issues and activities. It would also facilitate inter-country collaboration on seed science and technology in existing networks and would support the establishment of new networks where necessary. In addition, the Consultative Group would act as a catalyst to promote improved seed supply and plant genetic resources conservation, evaluation and utilization in the region.

[42] Participation would be voluntary, with formal status designated and approved by respective member governments. The Consultative Group would be composed of institutions from each member country (represented by a national focal point), international institutions that were active in the region’s seed sector, representation from the national seed (or seed trade) association(s) - or from a seed company in cases where no national seed association existed - and invited resource persons.

[43] The name proposed for this Inter-Governmental body was the Consultative Group on Seed Sector Development for Central and Eastern European Countries, Commonwealth of Independent States, and Countries in Transition, and was given the acronym CGSSD-CEEC/CIS/CT.

[44] To address regional, policy, regulatory, scientific and technical issues of a difficult nature, CGSSD-CEEC/CIS/CT would be supported by a number of specialized Working Groups. These Working Groups would link the seed initiatives in different parts of the region to the CGSSD-CEEC/CIS/CT, which in turn would connect to other regional initiatives on seed industry development, and PGR conservation and utilization.

[45] The Consultative Group would also play a role in harmonizing and strengthening ongoing networking initiatives in seed and PGR conservation and utilization, and promote new undertakings at national and subregional levels. In this respect, the existing regional and inter-regional networks - such as the East European Seed Network (EESNET) - were identified to actively participate in the Consultative Group.

[46] CGSSD-CEEC/CIS/CT would encourage the participation and collaboration of interested countries, institutions and organizations in this endeavour.

[47] The Meeting recommended that FAO explore the possibility of assisting in the establishment and launching of activities of the Consultative Group. FAO was also requested to provide support for harmonization and guidance on scientific, technical, policy and regulatory issues and to explore possibilities for financial support for the activities of the Consultative Group.

3.1 Coordination and strategy of the Consultative Group

[48] The General Meeting of CGSSD-CEEC/CIS/CT would be convened every two years and would be overseen by a chair and a vice chair elected by the Meeting. The first General Meeting was tentatively scheduled for 2002.

[49] An Interim Coordinating Committee (ICC) was established to work in close collaboration with FAO to maintain the momentum generated at the Technical Meeting, and to carry out activities towards the constitutional establishment of CGSSD-CEEC/CIS/CT. The ICC would be composed of a General Coordinator and a Deputy General Coordinator, and the Coordinators of the Working Groups designated during the adoption of the report of the Technical Meeting. The date and place of the first ICC meeting would be decided in consultation with FAO and was tentatively scheduled to take place in September 2001. The participants at the meeting selected the delegate from Hungary, Dr Zoltán Bedo, as the General Coordinator of ICC, and Professor Karol W. Duczmal as Deputy General Coordinator. It was envisaged that ICC would conclude its work when the first General Meeting was held.

[50] Five Technical Working Groups were defined to carry out the activities identified as pertinent to the development of the seed sector in the CEEC/CIS/CT region. Each Working Group would be led by a designated coordinator. The Working Groups were given titles reflecting the seed-related issues to be addressed by each group, namely:

1. Seed strategies and policies.

2. Harmonization of seed legislation and regulations.

3. Plant genetic resources and crop germplasm.

4. Cooperation in seed-related research, extension and education.

5. Regional seed information system.

[51] Technical Working Groups would organize meetings on specific technical topics. Associating these meetings with other national and international workshops, symposia or conferences would be pursued to facilitate participation. All group Coordinators were requested to officially confirm their acceptance to the ICC Coordinator, with copy to the Chief, Seed and Plant Genetic Resources Service, FAO, within three months.

[52] Designation of coordination responsibilities would be subject to periodic review at each CGSSD-CEEC/CIS/CT meeting, and revisions made whenever necessary, with a view to ensuring that the Consultative Group and its Working Groups continue to receive all the support and leadership required. In this regard, questions related to the functioning of the Working Groups would be referred to CGSSD-CEEC/CIS/CT, which would take temporary measures as needed to ensure efficient operations.

4. THE STRUCTURE OF THE CONSULTATIVE GROUP ON SEED SECTOR DEVELOPMENT FOR CEEC, CIS AND OTHER COUNTRIES IN TRANSITION (CGSSD-CEEC/CIS/CT)

5. THE ROLE AND FUNCTIONS OF THE INTERIM COORDINATING COMMITTEE AND OF THE CONSULTATIVE GROUP

5.1 Interim Coordinating Committee (ICC)

The Interim Coordinating Committee would make preparations for the establishment of the CGSSD-CEEC/CIS/CT, including the following specific actions:

Communicate with all countries and international organizations of the region in consultation with FAO to confirm their interest in participation in the Consultative Group.

Prepare information explaining the role of the Consultative Group proposed, and circulate this to interested parties, including through a website in association with FAO.

Prepare a draft constitution for the Consultative Group, taking into account the recommendations of the Meeting held in Budapest, so that such constitution could be approved at the first meeting of the Interim Coordinating Committee (ICC).

Prepare the first meeting of the ICC.

Coordinate the activities of the different Working Groups.

Promote specific meetings on technical subjects.

Promote efforts to obtain funding assistance from donors and aid agencies for the activities of the Consultative Group and the Working Groups.

5.2 Consultative Group on Seed Sector Development for Central and Eastern European Countries, Commonwealth of Independent States, and other Countries in Transition

The CGSSD-CEEC/CIS/CT would thereafter be responsible for the activities listed below, and for any other relevant issues:

Facilitate communication among the different Working Groups, as well as among regional seed and crop genetic resources networks.

Facilitate adaptation of the working arrangements of the Consultative Group to meet member requirements and to ensure efficiency of operations.

Cooperate to identify and obtain funding assistance from donors and aid agencies for strengthening its activities and those of the Working Groups.

Actively participate in issues and undertakings in the other regional initiatives and activities of FAO and other relevant regional institutions concerned with seed policies and programmes.

Oversee the coordination of the Working Groups and the management structure of the Consultative Group after its official status has been recognized.

Assist in the formulation of national seed programmes and projects.

Provide consultancy support to member countries.

To facilitate general communications and sharing of information, it was agreed that one or more websites should be developed. Duplication of the site in English and Russian would further facilitate communication. The FAO Seed and Plant Genetic Resources Service (FAO/AGPS) and the FAO Subregional Office for Central and Eastern Europe (SEUR) in Budapest would also provide linkages in their web site for this purpose.

6. WORKING GROUPS AND COORDINATORS

The Meeting identified specific issues to be addressed by the Working Groups, which would form the basis for the Consultative Group. Participation in the working groups would be open to any interested institutions, organizations and associations, as well as researchers, dealers and individuals from either the public and private sector.

6.1 The role and functions of the scientific and technical working group coordinators

The responsibilities of the technical working group coordinators would be to:

Develop and guide activities appropriate for the Working Groups.

Prepare and disseminate annual progress reports on Working Group activities and promote appropriate scientific and technical contributions to be included in the newsletter of CGSSD-CEEC/CIS/CT.

Promote specific meetings on technical subjects within their group’s area of activity.

Develop communications, through electronic and other media, to facilitate sharing of information and intra-group contacts.

Prioritize the work of their group according to resources available and the perceived needs of member countries.

The profile and provisional agenda of work for the five working groups were established by the meeting as follows:

WORKING GROUP I - SEED STRATEGIES AND POLICIES

Objective:

Promote and facilitate inter- and intra-regional movement of seed and varieties through appropriate policies and common strategies.

Activity Issues:

Privatization and liberalization.

Public-private sector partnership.

Role of the informal sector.

GMOs.

Seed security.

International collaboration.

WORKING GROUP II - HARMONIZATION OF SEED LEGISLATION AND REGULATIONS

Objective:

Promote and facilitate inter- and intra-regional movement of seed and varieties through harmonized or compatible legal and regulatory frameworks.

Activity Issues:

Variety registration.

Seed certification.

Intellectual property rights (IPRs).

Phytosanitary issues.

Biosafety.

Seed commercialization.

WORKING GROUP III - PLANT GENETIC RESOURCES AND CROP GERMPLASM

Objectives:

(i) Promote collaborative efforts for the conservation, characterization and evaluation of plant genetic resources.

(ii) Promote exchange of crop germplasm, and related information, among countries of the region.

(iii) Promote use of crop genetic resources in pre-breeding programmes.

(iv) Promote in situ conservation.

Activity Issues:

Monitoring and collection.

Conservation.

Characterization and evaluation.

Access to and utilization of crop germplasm.

Collaboration with other networks.

WORKING GROUP IV - COOPERATION IN SEED-RELATED RESEARCH, EXTENSION AND EDUCATION

Objectives:

(i) Promote knowledge sharing in the areas of research, extension and education.

(ii) Promote partnership and technology transfer among stakeholders in crop improvement and production of high quality seed

Activity Issues:

Biotechnology.

Seed technology.

Seed education and extension.

Seed training at all levels.

WORKING GROUP V - REGIONAL SEED INFORMATION SYSTEM

Objective

Develop an efficient regional information and database system incorporating existing national databases, for use of stakeholders in the region.

Activity Issues:

Database of varieties.

Database of seed stocks.

Database of seed suppliers.

Seed trade statistics.

6.2. Coordinators and Co-coordinators appointed by the Meeting

|

Interim Coordinating Committee (ICC): |

|

|

Coordinator: |

Mr Zoltan Bedo, Hungary |

|

Deputy Coordinator: |

Mr Karol W. Duczmal, Poland |

|

|

|

|

Working Group I |

|

|

Coordinator: |

Mr Anatoly Eroshenko, Russia |

|

Co-coordinators: |

Mr Boris Boincean, Moldova |

|

|

|

|

Working Group II |

|

|

Coordinator: |

Mr Mehmed Uyanik, Turkey |

|

Co-coordinators: |

Mr Vasiliy I. Soroka, Ukraine |

|

|

|

|

Working Group III |

|

|

Coordinator: |

Mr Sergey Alexanian, Russia |

|

Co-coordinator: |

Mr Isaak Rashal, Latvia |

|

|

|

|

Working Group IV |

|

|

Coordinator: |

Ms Anna Vitariusova, Slovakia |

|

Co-coordinator: |

Mr. Ivan Djurkic, Croatia |

|

|

|

|

Working Group V |

|

|

Coordinator: |

Mr Anatoly Rubanik, Belarus |

|

Co-coordinator: |

Mr Andrzej Szymanski, Poland |