Sanjay K. Nepal is Assistant Professor

in the Resource Recreation and Tourism

Program, University of Northern British

Columbia, Prince George, Canada.

2002 is also the International Year of Ecotourism - making it doubly timely to look at the impact of tourism in mountain areas.

Trekkers in the Everest region of Nepal

- S.K. NEPAL

The year 2002 holds a special significance for mountain regions throughout the world: not only is this the International Year of Mountains, but it is also the International Year of Ecotourism. Mountains, with their remote and majestic beauty, are among the most popular destinations for ecotourism, and mountain tourism can be a key factor in the focal concern for both events: the overall improvement in people's quality of life through sustainable development initiatives in economic development and environmental conservation. In both socio-economic and environmental terms, tourism in mountain regions is a mixed blessing; it can be a source of problems, but also offers many opportunities.

Hector Ceballos-Lascurain, who is given the credit for introducing the term "ecotourism", defined it as "travelling to relatively undisturbed or uncontami-nated natural areas with the specific objective of studying, admiring and enjoying the scenery and its wild plants and animals, as well as any existing cultural manifestations (both past and present) found in these areas" (Ceballos-Lascurain, 1987). The Ecotourism Society (1991) includes in its definition the improvement of the environment and the well-being of local people; it considers ecotourism to be "responsible travel to natural areas which conserves the environment and improves the well-being of local people". Many travel and tourism professionals and academics have dismissed ecotourism as an impractical, vague concept. Those in favour of ecotourism, however, consider it the answer to the problems of mass tourism and a last hope for saving endangered species, ecosystems and cultures. In spite of the controversy, there is a general agreement that ecotourism, if planned properly, can change the fortunes of people and places in remote and less developed regions. It is very relevant to the concept of mountain tourism, particularly for countries such as Nepal, where mountains constitute almost 80 percent of the land mass and are home to significant biological and cultural diversity.

Mountainous regions, in most cases, are inaccessible, fragile, marginalized from political and economic decision-making and home to some of the poorest people in the world. While steepness, fragility and marginality are often constraints, exposing mountains to pervasive degradation, they also provide attractions for tourism. Tourism develop-ment is an obvious means for achieving sustainable mountain development, parti-cularly where other economic resources necessary for development are limited.

Tourism is one of the largest industries in the world economy. The World Tourism Organization (WTO) predicts that by the year 2010 international tourism will involve 1 billion visitors and will contribute 11.6 percent to the global gross domestic product (GDP) (WTTC, 1999). Similarly, it is estimated that by 2010 roughly 250 million people will be employed in the tourism industry and 10.6 percent of total capital investments will be made in the tourism sector (WTTC, 1999). This estimate does not take into account the value of domestic tourism, so the real economic value of global ecotourism is much greater. Although in the light of recent international events such predictions are unreliable, the significant impacts and implications of global tourism and ecotourism cannot be ignored. WTO suggested that the global turnover of ecotourism in 1997 was US$20 billion (WTO, 1998).

It is estimated that mountain tourism constitutes 15 to 20 percent of global tourism (Mountain Agenda, 1999). Although this figure may sound high, it should be borne in mind that mountains in developed countries (particularly in western Europe) are destinations for mass tourism, in which high volume and high output are the norm. For example, in Austria, where tourism contributes more than 6 percent of the GDP and annual per capita income from tourism is roughly US$1 900, more than 75 percent of the total sales in tourism is generated by the alpine tourism industry (Smeral, 1996).

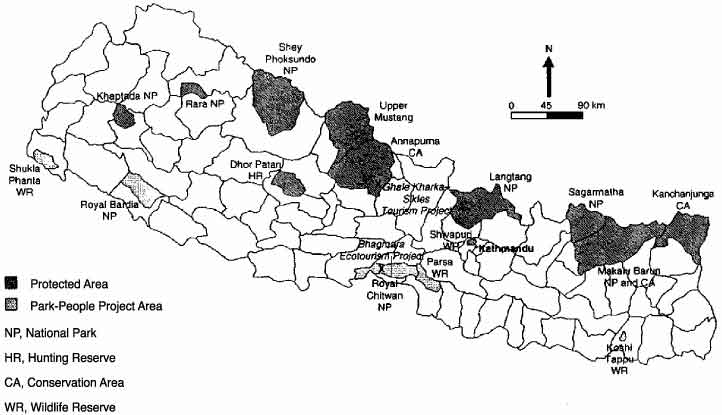

Protected area network in Nepal

Mountain areas include more than 475 protected areas in 65 countries covering more than 264 million hectares. Additionally, 140 mountain areas have been designated as biosphere reserves by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Protected areas include national parks where tourism is encouraged and promoted. In conservation areas in Nepal, as in game and wildlife reserves in many south African countries, sustainable forms of tourism are encouraged as a means of promoting wildlife conserva-tion and meeting the livelihood needs of local people (Nepal, 1997).

In Nepal, mountain tourism constitutes between 20 and 25 percent of total volume of tourism, but it is a significant income source for numerous people living in and around popular mountain destinations such as the Everest and Annapurna regions (Nepal, 1999). Most tour operators in Nepal promote mountain tourism as adventure and ecotourism; if visitors to national parks and wildlife reserves are considered, then it appears that 40 to 50 percent of all visitors to Nepal participate in some form of ecotourism; it is thus a major draw for international visitors to the country.

Given the current trend in nature-based tourism and the popularity of mountain destinations for nature tourism, it is reasonable to assume that many mountain regions will experience a significant growth in both international and domestic tourism. However, exposure from tourism can leave mountain communities vulnerable to severe environmental consequences and disruption of local culture and traditions, as has happened in many mountain destinations around the world. Thus, it is essential that mountain tourism be based on the principles of sustainability, which emphasize sound environmental practices, equity and long-term benefits for all stakeholders.

Mountain tourism in Nepal is concentrated mainly in the Annapurna, Everest and Langtang regions, which are protected areas (see Map). Annapurna is a conservation area, defined as an area where biodiversity conservation and traditional use of resources are both considered. The Langtang and Everest regions are home to two national parks: Langtang National Park and Sagarmatha National Park. Mountain tourism in Nepal is concentrated in these three areas partly because they were explored by early foreign mountaineering expedition teams and made popular through their writings.

Uncontrolled tourism has resulted in serious garbage pollution in the Himalayas, but local initiatives have been established to tackle the problem

- S.K. NEPAL

Other mountain destinations lack access and tourism infrastructure, and are less known to outsiders. The Nepalese government has not been able to divert the necessary resources to develop and promote tourism in these areas, partly because tourism in the country is a supply-driven industry, i.e. it responds to the demands of foreign visitors rather than developing and packaging a product to create the demand.

The country has experienced only a few decades of tourism development. Until 1950, Nepal was closed to foreign visitors apart from foreign dignitaries and individuals with special status, whose travel was restricted to Kathmandu. It was not until 1955 that Thomas Cook offered the first organized tour of Nepal for Western visitors. The advent of organized mountain trekking in the late 1960s affirmed its position as a popular international destination. Until the late 1970s the Nepalese Himalayas were considered an exotic destination, but their Shangri-La image has gradually been transformed to that of a cheap, rugged and dirty destination popular mainly for budget backpackers.

Tourism in the European Alps has become increasingly restricted and regulated, with strict regulations and control of the quality of services and facilities, and environmental measures such as emission and pollution standards and appropriate measures for solid waste disposal and treatment of sewage. In contrast, mountain tourism in the Nepalese Himalayas has been charac-terized by unregulated, uncontrolled and haphazard development. The lack of regulation in Nepal has led to landscape degradation; garbage pollution; increased extraction of valuable resources such as fuelwood and timber, contributing to increased loss of tree and shrub cover; sharp rises in property values; local inflation of the costs of goods and services; alienation of local residents caused by overwhelming numbers of visitors; and deterioration of traditional values (Byers and Banskota, 1992; Stevens, 1993).

Trekking traffic puts great pressure on mountain trails such as this degraded one near Namche

- S.K. NEPAL

The large concentration of visitors in some mountain destinations has resulted in alarming levels of tourism-induced environmental, socio-economic and cultural problems. In the Everest and Annapurna regions, local people are greatly outnumbered by visitors. For example, during peak tourist season in the Everest region, there may be as many as four visitors for every Sherpa resident. Human pressure - both from tourists and from seasonal migrants from neighbour-ing villages looking for jobs - has increased fuelwood consumption in erstwhile small, traditional villages, contributing to increased loss of tree and shrub cover in adjacent forests. In autumn 1997, 9.2 tonnes of fuelwood were burned daily in the 224 lodges in the Everest region (Nepal, 1999). This was equivalent to 24 percent of all fuelwood consumption in the region.

Another issue that has received much attention in the Himalayas is the accumu-lation of garbage left behind by trekkers and mountaneers, including food cans and wrappers, bottles, empty oxygen cylinders, spent batteries and ropes. These materials accumulate quickly and pose disposal problems.

Tourism provides income not only to porters carrying goods for tourists, but also to those who carry merchandise for lodge owners and traders doing business in tourist areas

- S.K. NEPAL

The problem became so significant that the Everest trail was labelled "the garbage trail" and the "highest dump on earth". The situation has been less severe in the Annapurna region, as local people have promptly organized community clean-up efforts. In the Everest region, in 1991, the Sagarmatha Pollution Control Committee (SPCC), a Sherpa-run non-profit organization, was established to tackle this problem. Since then, it has collected up to 250 tonnes of garbage per year, and the Everest trails and villages look much cleaner. On various occasions empty beer bottles have been airlifted to Kathmandu, and more recently import of bottled drinks has been prohibited.

Also significant is trail erosion caused by increased trekking traffic. In a survey undertaken in 1996 and 1997, trail-related problems included excessive widening, deep incisions, exposed bedrock, exposed mineral soil, trail displacement, exposed tree roots and running water on the trail. Trails tended to be more degraded at higher altitudes, in areas where ground vegetation was poor, on steep gradients and in areas with high trekking traffic and high concentra-tion of tourist accommodations (Nepal, 1999). Altogether, severely damaged trail sections in need of immediate maintenance added up to a total length of 10 km, or almost 11 percent of the main tourist trails in Sagarmatha National Park.

Despite the above-mentioned environ-mental problems, tourism in the Nepalese Himalayas has been a boon to the local economy. There may be no better example of locally controlled tourism than in the Everest and Annapurna regions. Lodge and restaurant owners, porters, guides and staff are overwhelmingly from local villages. The only exceptions are the porters in the Everest region, who come from neighbouring highland districts of Nepal - taking the place of many local Sherpas who started as porters but moved up the economic ladder and are now owners and managers of lodges, trekking agencies and Himalayan mountaineering expeditions. Almost 70 percent of trekking agencies based in Kathmandu are believed to be either fully or partly owned by Sherpas from the Everest region.

The magnitude of income and employment effects of even a relatively (globally speaking) small-scale tourism can be significant in a local context. For example, it is estimated that during peak tourist season, 65 000 trekkers in the Annapurna region provide seasonal jobs to more than 50 000 people. In one year at Sagarmatha National Park the arrival of 17 000 trekkers resulted in the employment of 14 000 porters, 2 500 guides and staff, 2 800 yak owners and 14 000 merchandise porters (carrying goods for Sherpa lodge owners and other traders in the tourist region). In the Annapurna region, ethnic groups such as the Gurung, Thakali and Magar have become affluent as a result of tourism.

In spite of all the positive changes, there are some negative changes as well. While tourism has improved the village economy, increased inequalities in levels of affluence among highland ethnic groups are also reported. Tourism has widened the gap between rich and poor people in villages, creating distinct social stratification. For the poorer sections of the society, the development of tourism has restricted access to previously accessible natural resources. For the more affluent, tourism has meant new aspirations, new consumption habits and ways of life, a broader horizon and a prosperous future.

Increased awareness of the harmful effects of tourism on the environment has become a catalyst for activities such as tree planting in the Everest region

- S.K. NEPAL

Several authors have reached the conclusion that the environmental and social carrying capacities of tourism in the Nepalese Himalayas have already been exceeded (Brown et al., 1997; Shackley, 1996). However, this author does not support this perspective; it is not based on detailed analysis of the positive and negative effects of tourism, and carrying capacity is subject to various interpretations. Although tourism in the Nepalese Himalayas has not been overwhelmingly positive, positive changes for the livelihoods and the environment of the mountain dwellers are slowly taking place and will gain momentum given the right institutional and political setting in the country and support from the international community (Nepal 1999, 2000). Remote regions such as Everest and Annapurna would have lagged behind in economic development had there been no potential for tourism development. Today, these are among the most prosperous highland areas in the Nepalese Himalayas.

Indicators of tourism-induced changes in Nepal TOURISM AS A CONSERVATION TOOL

TOURISM AS AN INCOME AND EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY

Source: Nepal, 2000. |

Tourism has had profound negative impacts on the environment, as illustrated above; however, as a result of increased awareness of the harmful effects of tourism and appreciation of its potential to benefit local livelihoods, issues related to tourism and the environ-ment have become a central concern of local communities. Tourism has provided the necessary platform for policy-making and the incentives for local communities and organizations to address not only tourism-induced negative environmental impacts but also broader concerns for environmental management and sustain-able development.

For example, tourism has resulted in a change in local people's attitudes towards nature and wildlife conserva-tion. Many villagers (at least those who have benefited from tourism) now support wildlife conservation efforts. The Annapurna Conservation Area Project (ACAP) has successfully demonstrated that conservation is possible if programmes are developed that suit local needs and conditions. In the previously poor village of Ghandruk, for example, ACAP's pilot project in integrating conservation and development resulted in the establishment of excellent community facilities including a model high school, a community health post, a well maintained drinking-water supply system, a Gurung museum, a women's cooperative shop and a community-owned and managed electricity distri-bution system. All households have toilets, village paths are paved and most households are relatively affluent. Much of Ghandruk's barren land has been planted with trees (Thakali, 1997).

Through Amatoli (mother's group) programmes in Ghandruk and Chomrong villages in Annapurna, women actively raise funds from tourists and locals through cultural events and festivals, and invest the money in community activities such as trail repairs, village clean-ups and literacy programmes - raising women's profile from ignored housewife to a powerful presence in village devel-opment activities. Mountain tourism has given strength and legitimacy to several formal and informal village-level institutions. Traditional institutions have been revitalized, for example the tradi-tional forest guardian system prevalent among the Khumbu Sherpas, and new institutions such as SPCC have been established to improve environmental conditions. Tourism in the Nepalese Himalayas has become a conservation tool, a social catalyst and an income and employment provider (see Box).

Innovative programmes such as ACAP, collaborative arrangements between the government and various non-governmental agencies for tourism-related projects (see Table), policies in favour of strengthening local-level capacity to resolve local issues and greater involvement of women in conservation and development projects have succeeded in bringing positive changes in the Nepalese Himalayas.

Institutional arrangements for protected area management | |||

Institutions involved |

Approach |

Protected area managed |

Programme thrusts |

(in order of importance) | |||

Government: |

Top-down, traditional |

Most national parks and |

Wildlife conservation |

Non-governmental organization (NGO): |

Community-based, |

Annapurna Conservation |

Community development |

Government and NGO: |

Upper Mustang (part of ACA) |

Quality tourism | |

Government and international NGO: |

Community-based, some |

Makalu-Barun National Park |

Community development |

Government and international NGO: Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation and World |

Kanchanjunga Conservation Area |

Biodiversity conservation | |

If tourism is based on principles of sustainability and equity, it can be instrumental in improving the livelihood conditions of mountain communities and increasing their stakes and interests in local, regional and national policy issues. Sustainability encompasses ecological, economic and social components. In the context of tourism development, this means that both the types and intensity of tourism activities in the mountains must have limits, and that benefits must reach a larger community. Thus it is clearly necessary to monitor, regulate and control activities that may jeopardize the resource base on which mountain tourism depends. Economic and social monitoring are also important to ensure that differences in income and employment from tourism do not create social friction or disharmony. Ecotourism plans should not only focus on resource conservation but should also address issues of equity, community development and social harmony.

Sustainable mountain tourism encompasses three basic components: conservation of natural resources on which tourism depends; improvement in the quality of life of the local population; and enhancement of visitor satisfaction. For these to be realized, effective policies and control mechanisms, strong local and regional institutions and sound manage-ment capabilities - based on both modern and traditional knowledge systems - are necessary. Without these essential elements, mountain tourism could easily be a short-term boom-and-bust enterprise.

Without adequate local control, self-reliance and strong participation in decision-making, tourism is likely to benefit only a few rich individuals, often outsiders, at the expense of a large, poor section of the community. Mountain communities are often limited in financial, technical and managerial resources, which hinders their ability to develop and market tourism attractions effectively. It is often the outside stake-holders such as tourism developers, entrepreneurs and tour operators who have the knowledge and the resources to make tourism a competitive business. Thus, mountain tourism policies must carefully balance the interests of local communities with those of outside stake-holders. Government institutions with the necessary capacity to plan and implement projects are crucial for the sustainable development of the highland regions.

As recent international events have indicated, tourism is vulnerable to outside forces, and it is risky to rely too much on tourism as the only economic development opportunity. Mountain tourism must be planned as part of integrated regional economic develop-ment; tourism should encourage investments in other activities. In the mountain context, this means diver-sifying the local economy through the integration of tourism with agriculture, livestock development and other forms of small-scale enterprise that will keep the village economy sustainable in the event of declining tourism activities. Mountain tourism policies should focus on enhancing and strengthening such linkages.

Opportunities from mountain tourism are great, not only in the Himalayas but all over the world - as long as plans and policies are in place to ensure that tourism does not pose an environmental and social threat. This threat calls for a judicious use of natural (tourism) resources, community planning, local awareness and reliance, strong local institutions and policies and a vision for the long-term sustainability of tourism projects. Mountain tourism in the Nepalese Himalayas represents the dilemma of conservation and develop-ment that is currently being debated in the context of sustainable development. If the mystical, spiritual and wilderness image of the Nepalese Himalayas is to be restored and capitalized on, then there must be concrete efforts towards tourism development that is sustainable in ecological, economic and social terms. The Nepalese experience in mountain tourism offers valuable lessons for international mountain communities.

Bibliography

Brown, K., Turner, R.K., Hameed, H. & Bateman, I. 1997. Environmental carrying capacity and tourism development in the Maldives and Nepal. Environmental Conservation, 24(4): 316-325.

Byers, A. & Banskota, K. 1992. Environmental impacts of backcountry tourism on three sides of Everest. In World heritage twenty years later, p. 105-122. Gland, Switzerland, World Conservation Union (IUCN).

Ceballos-Lascurain, H. 1987. The future of ecotourism. Mexico Journal, January: 13-14.

Ecotourism Society. 1991. Ecotourism guidelines for nature-based tour operators. Vermont, USA.

Mountain Agenda. 1999. Mountains of the world - tourism and sustainable mountain development. Berne, Switzerland.

Nepal, S.K. 1997. Sustainable tourism, protected areas, and livelihood needs of local communities in developing countries. International Journal of Sustainable Development and World Ecology, 4: 123-135.

Nepal, S.K. 1999. Tourism-induced environmental changes in the Nepalese Himalaya: a comparative analysis of the Everest, Annapurna, and Mustang regions. Ph.D. dissertation, Faculty of Natural Sciences, University of Berne, Switzerland.

Nepal, S.K. 2000. Tourism, environment, and society: development and change in the Nepalese Himalaya. Synthesis report of the Nepal Tourism Study Project. (Draft)

Shackley, M. 1996. Too much room at the inn? Annals of Tourism Research, 23: 449-462.

Smeral, E. 1996. Importance and development of Austria's alpine tourism industry. In K. Weirmair, ed. Proceedings - Alpine tourism, sustainability: reconsidered and redesigned, p. 2-11. Innsbruck, Austria, University of Innsbruck.

Stevens, S.F. 1993.Claiming the high ground. Sherpas, subsistence, and environmental change in the highest Himalaya. Berkeley, California, USA, University of California Press.

Thakali, S. 1997. Local-level institutions for mountain tourism and local development. (Draft)

World Tourism Organization (WTO). 1998. WTO News. January/February.

World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC). 1999. Travel and tourism's economic impact. Brussels, Belgium.