European Commission

Directorate General for

Fisheries

Rue Joseph II, 99

B-1049

Brussels

Belgium

Tel: +32 2 2990180

Fax: +32 2

2994802

E-Mail: [email protected]

(With particular thanks to Hans-Joachim Rätz at the Institute for Sea Fisheries in Hamburg and to ICES)

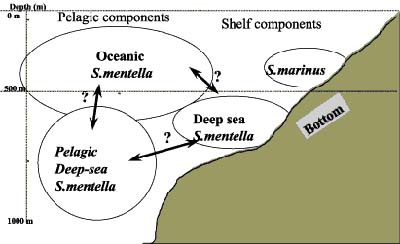

Biology of pelagic redfish in the North Atlantic Ocean

There appear to be two distinct redfish components in the area of the Irminger Sea, which is in the North Atlantic west of Iceland. The first are the shelf components, which consist of Sebastes marinus, occurring at depths generally above 500 metres and deep sea Sebastes mentella normally found below this level. The second components are the “oceanic” and “pelagic deep-sea” forms found in the Irminger Sea and they are sometimes referred to as pelagic redfish in order to differentiate them from the redfish associated with the slope and shelf areas. Indications are that these may consist of oceanic Sebastes mentella, found at both depths though mostly in the upper one, and pelagic deep-sea Sebastes mentella found mainly at the lower depth. Nevertheless, there are substantial overlaps between the various stock components of Sebastes mentella and the relationships between them are both complex and not clearly differentiated. Genetic studies which have been published, on not able to conclude on whether the three forms of Sebastes mentella are genetically distinct.

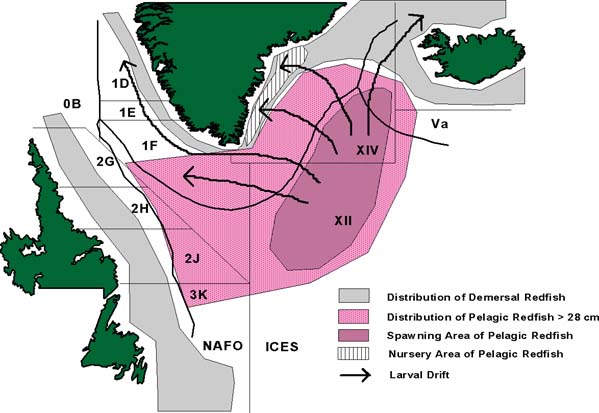

Figure 1 - Schematically possible relationship between different stocks of redfish in the Irminger Sea and adjacent waters

Trawlers using demersal and pelagic trawl have caught most of the redfish caught in Division Va. The major part of the catches are taken by Iceland, although there are catches in this area by the United Kingdom, Germany and the Faroe Islands.

In Division Vb, the redfish are caught mainly with demersal trawl, with the Faroese catches comprising more than 90% of catches. Occasionally, the fleets of France or Germany target the fisheries. The remainder of the catches taken in the division are by-catch in other demersal fisheries.

In Sub-area VI, redfish are taken by several countries and are considered to be mainly by-catch in demersal fisheries.

In Sub-area XII, the catches taken are mainly of pelagic Sebastes mentella and are taken by pelagic trawls with fisheries conducted by a number of countries, including the Russian Federation, Germany, Faroe Islands, Iceland and Norway.

Regarding Sub-area XIV, both Sebastes marinus and Sebastes mentella stocks are exploited. Since 1990, the main fleets conducting the fisheries have been from the Russian Federation, Norway, Iceland and Germany although in more recent years, vessels from several other countries have joined these fisheries conducted in the main outside the Greenland and Icelandic EEZs.

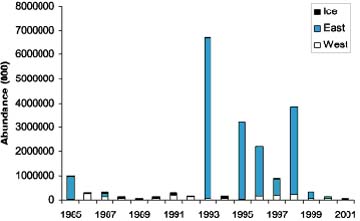

Figure 2 - Sebastes mentella (< 17cm). Survey abundance indices for East and West Greenland and Iceland derived from the German and Icelandic groundfish surveys, 1985 to 2001

Throughout the 1980s and the 1990s until 1997, surveys in both the Convention Area of the North East Atlantic Fisheries Commission (NEAFC), (in the Exclusive Economic Zones of Greenland and Iceland, as well as on the high seas) and nearby showed decreases in abundance towards NAFO Division 1F to the south and to the west. Some scientists had felt that the area surveyed before 1997 had covered the majority of the stock range.

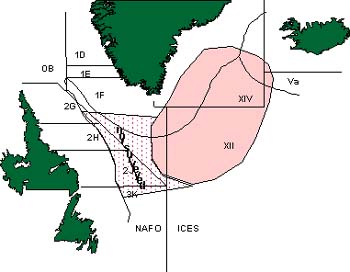

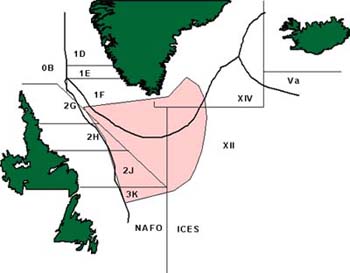

Figure 3 - Survey information on the main distribution of pelagic redfish in June/July 1992-1997 and 1999-2001 above 500 m depth.

3A - June / July 1992 - 1997

3B - June / July 1999 - 2001

In 1999, the survey was expanded and more fish were found to the south and west. A high abundance was observed at the western border of the survey. The stock may have been moving in a westward direction into the adjacent waters managed by NEAFC’s sister organisation, the Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organisation (NAFO), and was extending towards the Canadian EEZ. For the first time in the surveys, redfish below 28 to 30cm were found. Based on charting of extrusion and 0-group abundance, it was clear that the extrusion and larval areas were mainly off East Greenland. Furthermore, the feeding areas were stretching into the NAFO waters of Division 1F.

Figure 4 - Distribution area of demersal and pelagic deep-sea redfish (Sebastes mentella), nursery grounds and larval drift

Reasons for the migration of the stock remained unknown and it was unclear whether the movement was permanent or not. One theory links the migration to a general increase in the sea temperature. The occurrence in NAFO waters was entirely seasonal (from June until November) with the redfish returning to NEAFC waters in late autumn. Furthermore, there were no spawning grounds in NAFO waters and the redfish in NAFO waters consisted mainly of so-called “upper-layer fish”, with insignificant quantities of redfish in the level below 500 metres.

In other words, there was no evidence of a distinct redfish stock in NAFO waters. Nevertheless, there was a certain movement from the NAFO side, which seemed to argue for a small but distinct NAFO redfish stock in those waters. However, it seemed that the NAFO Scientific Council did acknowledge that the redfish in NAFO Division 1F was “part of the oceanic redfish stock previously being distributed in the NEAFC Convention Area”.

Nevertheless, it is also possible that these areas of redfish abundance were not a new occurrence but rather a new discovery made when the surveys were extended.

What did become clear was that further research and enhanced scientific knowledge were needed.

Regulation of redfish in the North East Atlantic

For a number of years, fisheries for pelagic redfish in the Irminger Sea have been regulated and managed by NEAFC. For the first time in 1996, NEAFC established a total allowable catch (TAC) with a TAC set at 153 000 tonnes for the NEAFC Convention Area, covering fisheries both inside and outside the EEZs of the Contracting Parties.

The six Contracting Parties of NEAFC all have different interests in this stock. It occurs mainly inside the EEZs of Greenland and Iceland and also in international waters. Historically, some of the Contracting Parties have established a long-term record of fishing activities in the areas in question. Others have contributed towards establishing a better understanding of the science of the stock by carrying out research over a number of years. So when the TAC and sharing was established, it was necessary to take into account all sorts of factors giving foundation to the claims of the various Parties.

Between 1996 and 1999, all Contracting Parties with the exception of the Russian Federation accepted the TACs and quotas established by NEAFC. Unlike other regulated species in the NEAFC context, the TACs for redfish in NEAFC have not been set according to the model of staged co-operation, whereby the coastal States first agree on restrictions for their own fisheries, with NEAFC establishing compatible measures for the high seas portion of the stock, as is the case for other stocks in NEAFC (Atlanto-Scandian herring and mackerel). Originally, the TAC was established for the NEAFC Convention Area, including the EEZs of both Greenland and Iceland. At the NEAFC Annual Meeting in November 2000, Iceland made it clear that they felt that it was preferable to have a quota system reflecting scientific advice, even though that advice is somewhat imperfect. From then on, they have established their own autonomous quotas. Nevertheless, the other Contracting Parties took due regard of Iceland’s interest by leaving a proportion of the TAC unallocated both for 2001 and 2002.

The TAC for 2002 shared between all six NEAFC Contracting Parties is 95 000 tonnes, although this has not been acceptable to either Iceland or the Russian Federation. With a proposed quota in 2002 of 24 169 tonnes, the Russian Federation established an autonomous quota of 32 000 tonnes. Provision had been made for a possible quota in Icelandic waters for the same period of 27 008 tonnes for Iceland. They fixed autonomous quotas of 13,000 and 32 000 tonnes to be fished in two different areas. The Russian Federation is dissatisfied with the level of quota, which has been allocated to them, whilst Iceland has a fundamental difference of opinion on the method of management of the redfish in the North Atlantic.

In the meantime, ACFM had been asked to review the advice it had given for 2002 at its meeting in May 2002. The result of this review was that ACFM considered that the stock could sustain a maximum exploitation for 2002 and 2003 equivalent to current catch levels, which over the last five years have averaged 119 000 tonnes. Nevertheless, no change to the existing regulatory measure for 2002 has yet been agreed in the NEAFC context.

With the movement of the stock into NAFO waters, NEAFC has had every interest in ensuring that adverse effects for the stock as a whole were avoided.

What is the practical result of this change in the location of this redfish stock?

There is now legitimate scope for NAFO Parties to start fishing on this stock in its waters. This is despite the fact that both the assessment and the management of the stock have until now been the sole responsibility of NEAFC. Some NAFO Contracting Parties have seen this as an opportunity to acquire new fishing possibilities. They may even have been motivated to seek solutions for this problem, which would disregard the biological unity of the stock. Other NAFO Contracting Parties might have been expected to have some misgivings with NEAFC becoming the main stakeholder of a stock within a NAFO context. The whole situation gave rise to great controversy and potential antagonism between the Contracting Parties of the two fisheries organisations.

There were almost no precedents for a situation such as this one, where a fish stock straddles between the Convention Areas of two regional fisheries organisations. We know that certain tuna conventions do include special co-operation and consistency requirements for cases of overlaps with areas under regulation by other fisheries management organisations. Other than certain cases, such as that of southern blue-fin tuna, where there has been acquiescence of a regulatory priority for the organisation within which the bulk of the stock occurred, these requirements have not yet resulted in any formal arrangements.

The starting point in the discussion, which had to take place in both NEAFC and in NAFO, was the general co-operation and conservation obligations contained within the provisions of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Article 119 of UNCLOS makes it a requirement to inter alia take into account “fishing patterns”, i.e. the presumption in favour of the established use of the redfish. Also relevant was the “due regard requirement”, which implies the respect of existing fishing rights and therefore the rights established already by the NEAFC Contracting Parties. Furthermore, we were also able to draw upon the general ideas, which underlie the compatibility provisions of the 1995 UN Agreement on Straddling Fish Stocks, inasmuch as the principles of the biological unity of the stock and the pre-eminence of established regulated fisheries are concerned. The exercise we had to carry out had to give real meaning to these obligations and principles in respect of the redfish as a whole.

Based on these considerations, it was possible to identify a number of possible management options:

1. Extension of the NEAFC regulation into NAFO waters (where NEAFC establishes the TAC for the entire stock - any catches made in NAFO waters count against NEAFC quotas;

2. Establishment by NEAFC of a TAC for the entire stock, setting aside an agreed specific percentage for treatment by NAFO;

3. NAFO and NEAFC separately regulate the portions of stock, which occur in their respective waters. The two quantitative restrictions would add up to the TAC for the entire stock; and

4. A temporary moratorium on fishing for redfish in the NAFO Division 1F pending the successful outcome of the joint NEAFC-NAFO process.

The latter option was only to be contemplated as a last resort in the event that a dispute arose between NEAFC and NAFO.

The third option would have constituted the “jurisdictional” solution. However, it would have presupposed a permanent occurrence of the NEAFC redfish in NAFO waters. It would also have required a lengthy process in order to accurately determine the respective portions of the stock and explain how to establish compatible conservation measures.

For NEAFC Contracting Parties, the first option was obviously the ideal solution. However, it might have been very acceptable to the NEAFC Contracting Parties but much less so in the broader NAFO forum. One option remained, namely option two. This would allow for both an agreed solution and a rapid completion of the process, at the same time being as close as possible to the biological reality of the stock.

What has happened since NEAFC and NAFO decided to cooperate and jointly examine this situation?

In February 2001, NEAFC and NAFO held a joint working group meeting in order to explore possible ways to co-manage the oceanic redfish stock. This was to help prepare a decision to be taken at the Special Fisheries Commission of NAFO in Copenhagen in March 2001.

NEAFC had already taken a decision for the regulation of the redfish for 2001 under its responsibility at its Annual Meeting in November 2000. A TAC of 95 000 tonnes was agreed upon despite an objection from Iceland.

In NAFO, regulatory measures were adopted for the first time at the Special Fisheries Commission meeting of NAFO in Copenhagen in March 2001. These were considered as ad hoc measures until a definitive solution could be found, which:

did not prejudice either the interests of the NAFO Contracting Parties or of the NEAFC Contracting Parties;

remained consistent with the cooperation obligations of customary international law; and

recognized due regard for the existing NEAFC management measures.

The result agreed in March 2001 can be described as follows:

The extension of the management measures adopted for the NEAFC Regulatory Area (95 000 tonnes)into NAFO Division 1F, provided that catches taken in NAFO Division 1F are deducted from the NEAFC quotas and that vessels comply with the technical requirements (mesh sizes etc.) in NAFO when fishing in this area;

Despite the level of the TAC for 2001, a limit of 30 000 tonnes to be imposed on catches in NAFO Division 1F;

NEAFC be given the task of carrying out the scientific assessment for the stock and establishing the overall TAC.

The final result in NAFO remained contentious as of the thirteen Contracting Parties present at the meeting, only nine supported the proposal outright. The other four had a number of concerns. One was unsure of having a single TAC for two different organisations. Another wanted a moratorium until clearer scientific advice could be provided. A couple of Parties were concerned that not all NAFO Contracting Parties were given access to this fishery. A number of NAFOP Contracting Parties (Latvia, Lithuania and the Ukraine) subsequently objected to the ad hoc arrangement. Lithuania even established an autonomous quota of 5 000 tonnes.

Due to the very uncertainty hanging over the oceanic redfish in the North Atlantic, NEAFC and NAFO have had to continue to cooperate in this same manner.

For 2002, with NEAFC once again having agreed a TAC of 95 000 tonnes for the redfish stock, the same ad hoc measure was agreed between the Parties in NAFO. Lithuania once again objected and established an autonomous quota, this time at a level of 8 000 tonnes.

For 2003, NAFO agreed at its Annual Meeting in September 2002 to continue along the same vein but with a revised ad hoc arrangement. The new arrangement allocates 25 000 tonnes of redfish to be shared between the NEAFC Contracting Parties. A further 7 500 tonnes are allocated to other NAFO Contracting Parties, who are not Contracting Parties in NEAFC. This was a dramatic increase from the previous “others” quota of 1 175 tonnes and should be seen as an attempt to accommodate objecting Contracting Parties, in particular Lithuania. Furthermore, in account of the movement of the stock, the NAFO regulation now covers the sub-area 2 as well as Divisions 1F and 3K. The whole arrangement reflects the revised management advice produced by ACFM for 2002 and 2003, which implied an increased NEAFC TAC of 119 000 tonnes for the two years in question.

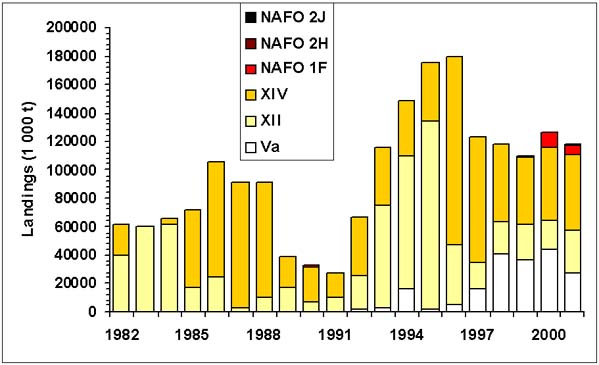

Figure 4 - International landings by ICES and NAFO divisions since 1982 as used by the ICES North-Western Working Group

Conclusion

In the North Atlantic, we have seen the need to cooperate on the pelagic redfish stock in the most appropriate manner possible.

The sharing of this stock is an interesting case to study in the sense that it is not only relevant as regards the sharing between EEZs and the high seas, but also in terms of sharing issues between adjacent regional fisheries organisations.

First of all, it has been necessary for the NEAFC Contracting Parties to cooperate amongst themselves. This has been done by the agreement on regulatory measures, which share out the stock, taking into account the legitimate rights of all the NEAFC Contracting Parties fishing in the Convention Area. By virtue of the distribution of the stock, this has necessitated a single regulation covering both waters under national jurisdiction, such as those of Iceland and Greenland, as well as international waters of the NEAFC Regulatory Area.

Having reached a limited arrangement within NEAFC, with the migration of the redfish stock, it has been necessary to cooperate on a much larger scale with NAFO, ensuring that any adverse effects for the stock as a whole could be avoided.

This has proved to be a very interesting and important exercise and demonstrates what can be possible in terms of co-operation between two neighbouring regional fisheries organisations, both of which have similar co-operation and conservation obligations for the fisheries in their respective areas.