CHAPTER FOUR

Ensuring access to food for all

Since the 1960s, market food prices have been low while food production satisfied market demand. However, FAO’s estimates indicate that in 1998 there were 815 million undernourished people in the world: 777 million in the developing countries, 27 million in countries in transition and 11 million in the industrialized countries. The world is capable of producing sufficient food to feed its population until 2030 and beyond (actually, a growing part of cereal production is already dedicated to animal feed). The 1996 World Food Summit set a target of reducing the number of undernourished people to 400 million by 2015. FAO projections indicate that this target may not be achieved before 2030. The normative target and the projection of the current course of events are illustrated in Figure 7.

Figure 7 Progress towards the World Food Summit target

The plight of undernourished people needs to be addressed through pro-active implementation of food-security programmes. Necessary policy adjustment should be tailored to ensure that people can apply their initiative and ingenuity to access food and establish a livelihood. Food security programmes should identify the most vulnerable categories of population and consider their assets and constraints in order to emerge from poverty. FAO has developed specific indicators for this purpose (see Box 3). A first level of support is emergency assistance to households that have been hit by natural, man-made or individual disasters. Households weakened by hunger and disease need to be restored to the necessary strength for being able to apply themselves to construction of a viable livelihood. At this point, people may need punctual support to realize their plans. External support may take a variety of forms, from provision of seeds and tools to capacity building and infrastructure development. Many poverty alleviation activities bear some relation with water. The role of irrigation is discussed further on.

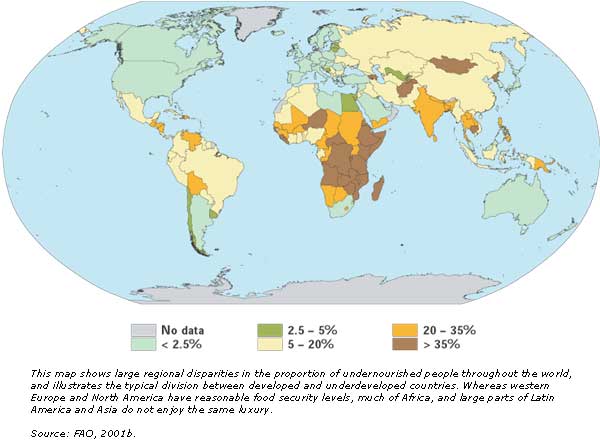

Figure 8 and map 3 identify the countries with the highest prevalence of undernourished people. Many of these countries have been stricken by war and natural disasters, including extended periods of drought. Within the countries, large numbers of undernourished people live in environmentally degraded rural areas and in urban slums. During the 1990s, the number of undernourished people fell steeply in East Asia. In South Asia, although the proportion fell, the total number remained almost constant. In sub-Saharan Africa, the proportion remained virtually unchanged, which meant that the number of undernourished people rose steeply. Food security action has therefore a special focus on sub-Saharan Africa.

Figure 8 Proportion of undernourished people in developing countries, 1990–1992 and 1997–1999

Map 3 Percentage of undernourished people by country (1998)

Many undernourished people are refugees who have lost their physical and social assets in displacement caused by war or natural disaster. The cause of displacement can also be unmitigated externalities stemming, for example, from urban development and consequent water pollution, as well as construction of dams and consequent flooding of the land. Some national macro-policies have failed to recognize the importance of agriculture and have also contributed to the forces pushing rural people into poverty. In rural areas, the people most affected include smallholders, landless labourers, traditional herders, fishermen and generally marginalized groups such as refugees, indigenous peoples and female-headed households. Children are particularly vulnerable to the full impact of hunger, which can lead to permanent impairment of physical and mental development.

Undernourishment is a characteristic feature of poverty. Poverty includes deprivation of health, education, nutrition, safety, and legal and political rights. Hunger is a symptom of poverty and also one of its causes. These dimensions of deprivation interact with and reinforce each other. Hunger is a condition produced by human action, or lack of human action to correct it. For example, in the early 1990s nearly 80 percent of all malnourished children lived in developing countries that produced food surpluses. Lack of access to water to provide basic health services and support reliable food production is often a primary cause of undernourishment. To eradicate hunger, abundant food production is a requirement, but in addition existing food needs to be accessible to all.

BOX 4 WATER AND FOOD SECURITY IN THE SENEGAL RIVER BASIN Parts of the Senegal River basin in Senegal and Mauritania are entirely situated in the arid Sahelian zone with, in the lower valley and the delta, a total annual rainfall that rarely exceeds 400 mm. Thus, when used in the low-lying areas, the rain-dependent crops of the plateau and flood-recession crops barely meet the food needs of farming families. During periods of drought like those of the 1970s, local populations are drastically affected; for this reason one of the four fundamental tasks for the Organization for the Development of the Senegal River (OMVS) at its founding in 1972 was ‘to create food self-sufficiency for populations in the Senegal River basin and, by extension, for the subregion.’ To this end the goal set was to develop 375 000 hectares out of a potential irrigable area of 823 000 hectares, by combined operation of the Manantali and Diama dams. The crops targeted for irrigation were rice and wheat, to be added to sorghum, maize and market gardening – the traditional rain-dependent and recession crops. With respect to this goal, a total of some 100 000 hectares has so far been developed. However, a 1996 study by the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) indicated that no single type of farming could guarantee the survival of the family unit and that crop diversification was essential. The study also pointed out the major issues in optimizing flood plain development as part of the fight for food security. These geographical areas are vital for agriculture, fishing, livestock pasture and forest regeneration. This is why, after the dams were filled in 1986 and 1987, OMVS decided to simultaneously expand the irrigated areas by delivering artificial flooding that would guarantee between 50 000 hectares and 100 000 hectares of recession crops and ensure 63 000 ha of pasture and wooded areas for 2.7 million cattle and 4.5 million sheep and goats. Fishing is also an economically and socially important activity in the Senegal River basin. With annual catches estimated at between 26 000 and 47 000 tons, it represents a substantial income for the populations concerned. The storage lakes of the Diama and Manantali dams – 11.5 million m3 spread over 500 km2 – have attracted large fishing communities since the dams became operational. The programmes begun by OMVS thus contribute to achieving food security in the area. For this aim to be met as quickly as possible, the OMVS High Commission sees a need, on the one hand, for increased technical, institutional and financial means so as to accelerate development and ensure sound management, and on the other hand, for technical improvements permitting more intensive farming, higher yields and a close association between farming, fishing, livestock-raising, forestry and the water economy. Source: Prepared for the World Water Assessment Programme (WWAP), by the Organization for the Development of the Senegal River (OMVS), 2002. |

There is a positive, albeit complex, link between water services for irrigation and other farm use, poverty alleviation and food security (IFAD, 2001; FAO, 2001a; FAO/World Bank, 2001). Many of the rural poor work directly in agriculture, as smallholders, farm labourers or herders. The overall impact can be remarkable: in India, for example, in unirrigated districts 69 percent of people are poor, while in irrigated districts, only 26 percent are poor (World Bank, 1991). Their income can be boosted by pro-poor measures, such as ensuring fair access to land, water and other assets and inputs, and to services, including education and health. Relevant reforms of agricultural policy and practices can strengthen these measures.

The availability of water confers opportunities to individuals and communities to boost food production, both in quantity and diversity, to satisfy their own needs and also to generate income from surpluses. Irrigation has a land-augmenting effect and can therefore mean the difference between extreme poverty and the satisfaction of the household’s basic needs. It is generally recognized that in order to have an impact on food security, irrigation projects need to be integrated with an entire range of complementary measures, ranging from credit, marketing and agricultural extension advice to improvement of communications, health and education infrastructure (see Box 4 for an example from Senegal). Land tenure may also represent a major constraint: irrigation schemes controlled by absentee landowners and serving distant markets, even when highly efficient, may fail to improve local food security when both commodities and benefits are exported.

Irrigation projects are as diverse as the local situations in which they are implemented. Generally, small-scale irrigation projects including projects based on shallow groundwater pumping provide a manageable framework that can give control to the local poor and avoid leaking resources to the non-poor. Large-scale irrigation, as may be determined by the need to carry out large-scale engineering works to harness water and convey it to the fields, can also be made to work for the poor provided that the benefits can be shared equitably, and investment, operation and maintenance costs are efficiently covered.

Community-managed small-scale irrigation systems, by improving yields and cropping intensities, have proved effective in alleviating rural poverty and eradicating food insecurity. Marketing of agricultural produce, both locally and at more distant places when adequate transport and communication infrastructure is available, can make a significant contribution to the income of farmers. Bank deposits and credits, as well as crop insurance, can be used to finance agricultural operations and buffer against climatic risk. However, banking services usually are not accessible to people who have no collateral assets. Many rural credit systems may also not accommodate pay-back over a period of years – the time needed to realize the benefits from investment in irrigation technology. However, non-conventional credit systems based on trust and social solidarity can support poor farmers. Improvement in poor people’s food commodity storage facilities reduces post-harvest losses and can save significant amounts of food, thus contributing to food security. Similarly, where technically and financially possible, storing water in surface reservoirs and aquifers is a strategic means for managing agricultural risk. Water in the reservoir or the aquifer is, in a way, equivalent to money in the bank.

Irrigation, supported through inputs such as high-yielding varieties, nutrients and pest management, together with a more extended agricultural season, higher cropping intensity and a more diverse assortment of crops, can generate rural employment in other non-agricultural services. The productivity boost provided by irrigated agriculture results in increased and sustained rural employment, thereby reducing the hardships experienced by rural populations that might otherwise drift to urban areas under economic pressure. Growth in the incomes of farmers and farm labourers creates increased demand for basic non-farm products and services in rural areas. These goods and services are often difficult to trade over long distances. They tend to be produced and provided locally, usually with labour-intensive methods, and so have great potential to create employment and alleviate poverty. Studies in many countries have shown multipliers ranging from two (in Malaysia, India and the United States) to six (in Australia, World Bank, 2002).

Fish has a very good nutrient profile and is an excellent source of high-quality animal protein and of highly-digestible energy. Refugees and displaced people facing food insecurity may turn to fishing for survival, where this possibility exists. Staple-food fish, often low-valued fish species, is in high demand in most developing countries, because of its affordability.

Inland fish production provides significant contributions to animal protein supplies in many rural areas. In some regions freshwater fish represent an essential, often irreplaceable source of cheap high-quality animal protein, crucial to a well-balanced diet in marginally food-secure communities. Most inland fish produce is consumed locally, marketed domestically, and often contributes to the subsistence and livelihood of poor people. The degree of participation in fishing and fish farming is high in many rural communities. Fish production is often undertaken in addition to agricultural or other activities. Yields from inland capture fisheries, especially subsistence fisheries, can be very significant, even though they are often greatly under-reported. Yields from inland capture fisheries are highest in Asia in terms of total volumes, but are also important in sub-Saharan Africa. Fishery enhancement techniques, especially stocking of natural and artificial water bodies, are making a major contribution to the total catch (FAO, 2000).

Rural aquaculture contributes to the alleviation of poverty directly through small-scale household farming of aquatic organisms for domestic consumption and income. It also contributes indirectly through employment of the poor as service providers to aquaculture or as workers on aquatic farms. Poor rural and urban consumers can greatly benefit from low-cost fish provided by aquaculture. For aquaculture to be effective in alleviating poverty, it should focus on low-cost products favoured by the poor, and emphasis should be placed on aquatic species feeding low in the food chain. The potential exists for aquaculture production for local markets and consumers. Combined rice-fish systems are possible and carry high benefits because they provide cereals and protein at the same time. These systems have also been shown to have beneficial effects on the malaria situation, where mosquito vectors breed in rice fields and where the selected fish species feed on the mosquito larvae. This is the case in parts of Indonesia, for example (see Box 5).

BOX 5 RICE-FISH FARMING IN LAOS Lao People’s Democratic Republic has extensive water resources in the form of rivers, lakes and wetlands. Fisheries and the collection of aquatic animals during the rainy season are important activities in the country and fish forms an important part of the national diet. Rice cultivation is widespread in rainfed, irrigated and terraced fields. Rice is mostly cultivated on a one-crop-per-year basis, but in irrigated areas two crops per year are possible. In upland rainfed fields, bunds are often raised to increase water depth for fish cultivation. In some cases, a small channel is constructed to facilitate fish capture. In the Mekong River plain, rice-fish farming is practiced in rainfed rice fields where soils are relatively impermeable as well as in irrigated rice fields, which offer ideal conditions for fish cultivation. As elsewhere, there is little reliable data available concerning production levels from rice-fish farming but productions of 125 to 240 kg/hectare/year have been reported for upland rice-fish production systems. Carp, tilapia and other species cultured in this system are mostly for consumption in the farmer’s home. While rice-fish farming is popular with farmers, there are some constraints that need to be addressed through proper support. Integrated pest management practices should be applied to reduce pesticide use. Furthermore, fingerlings need to be made available more easily and farmers’ access to credit should be improved. Source: Dixon et al., 2001. |

A large number of forest products contribute to food security: FAO estimates that about 1.6 billion people in the world rely to a certain extent on forest resources for their livelihoods. For most rural people in the world, firewood provides the fuel for cooking food, and so its availability is an integral part of food security. The bio-energy sector generates employment and income in developing countries.

Most forests and tree plantations subsist on rainwater, or may develop around irrigation schemes. Some tree species can use large amounts of water drawn from water storage in the soil profile and in shallow aquifers. Trees in forests and outside of forests provide significant benefits to poor people and contribute to food security. The benefits from water used by forests are largely seen in terms of wood and non-wood products, as well as in protecting the environment, reducing soil degradation, and preserving biodiversity.