Burjin, in the extreme northwest of China, about 48°N, has a cold, arid to semi-arid continental climate. Grazing lands are between 300 m and the summer snowline at 3 500 m. Stock rearing is the main land use and herders follow a traditional transhumance pattern. The long winter, when feed supply is a very serious problem, is spent on the desert fringe. Cattle, horses, sheep and goats are kept, with some baggage camels. Grazing rights are leased to households, which are responsible for the proper management of the pasture on a thirty-year basis; this can be revoked in case of mismanagement. Transit routes are defined officially and cannot be used as grazing; moving is organized to space out households on the trek routes. During the 1980s, a large area was developed for irrigated fodder, in rotation with crops, and selected households were allocated holdings for hay and crop production. These households have built houses as family bases, but continue to send stock on transhumance in the grazing season. The transhumance patterns of two groups, one with irrigated land and permanent housing and the other traditional nomads, were studied, together with their socio-economic conditions. There is ample summer pasture for 75-90 days. The highest pastures are just below 3 500 m, with winter grazing on the desert fringe between 300 and 1 000 m. The transhumance circuit can be up to 400 km. Families with irrigated land and hay had far higher incomes. Their herds are increasing and risks low; they also have good access to medical, educational and other facilities and are investing in production equipment and household goods. Lucerne yields are very low, far below their potential, largely because herders are unwilling to provide inputs. Winter weight loss in sheep has been converted to weight gain through shelter and feeding hay; such flocks can be mated earlier and lambs brought to slaughter weight in their first year. Nomadic families have lower incomes, little access to services and own what they can carry in their baggage train; their sheep still lose weight through winter and lamb late, so that many have to be kept through a second summer.

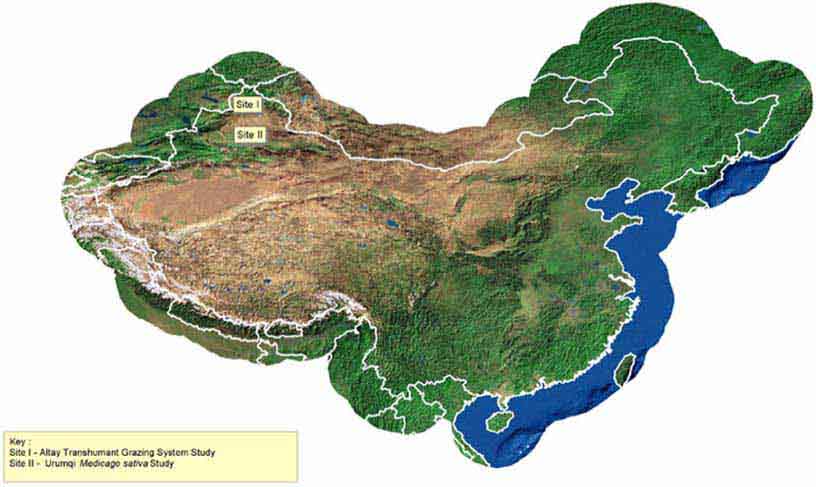

Xinjiang Autonomous Region is in the extreme northwest of China; Altai Prefecture is in the extreme northwest of Xinjiang, and Burjin County [“County” is used interchangeably for the whole administrative area and the county seat] is in the extreme northwest of the prefecture (see map - Figure 6.1) to the north of Junggar Basin, and southwest of the Altai Mountains, at 47°22´-49°11´ N and 86°25´-88° 06´ E. The distance from north to south is 200 km and from west to east it is 49-82 km. Its total area is 10 540 km2.

A large programme of provision of irrigated land for fodder in rotation, to supply hay for winter feed as well as allowing settlement of nomadic families, while maintaining transhumant production systems, has been undertaken in Altai Prefecture. The effects of settlement on herders were studied in comparison with households that still followed the traditional, fully nomadic life style.

FIGURE 6.1. Transhumant grazing system and Medicago sativa studies in northwest China.

Notes

Data subsetted from ESRI’s World Worldsat Color Shaded Relief Image. Based on 1996 NOAA weather satellite images, with enhanced shaded relief imagery and ocean floor relief data (bathymetry) to provide a land and undersea topographic view. ESRI Data and Maps 1999 Volume 1. Projection = Geographic (Lat/Long)

FAO Disclaimer

The designations employed and the presentation of the material in the maps do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of FAO concerning the legal or constitutional status of any country, territory or sea area, or concerning the delimitation of frontiers.

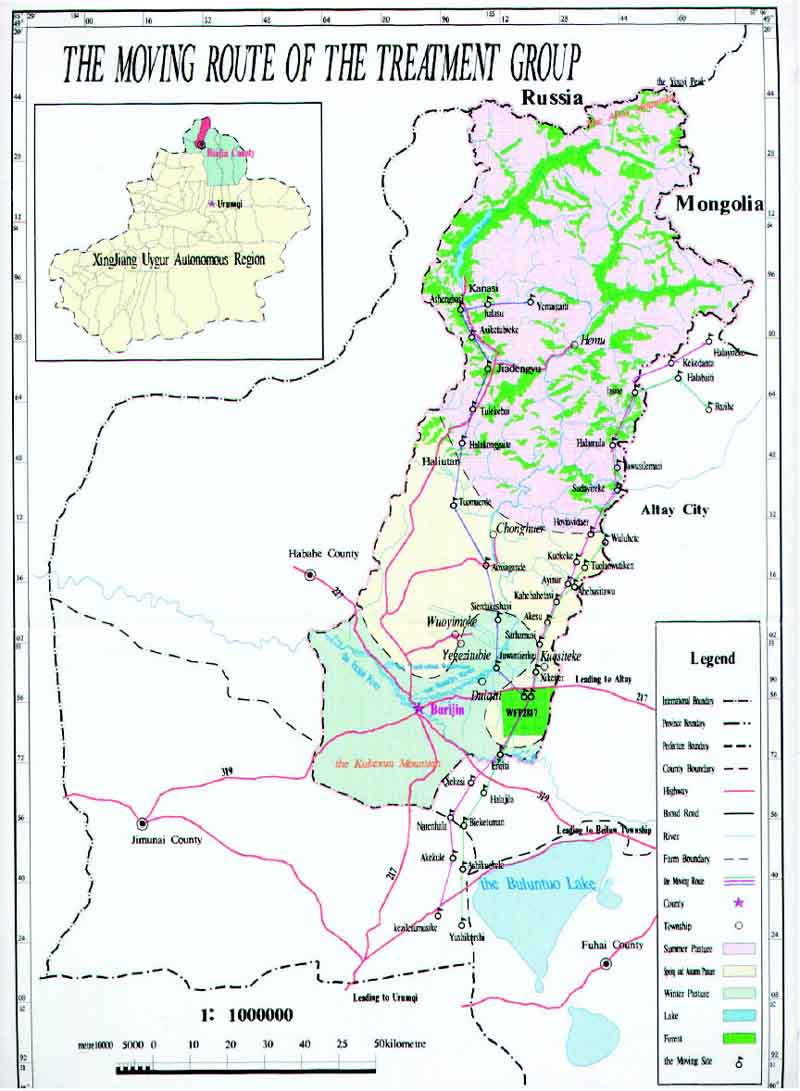

FIGURE 6.2. Location of the project’s fodder sites in Altai Prefecture, China.

Source: Li-Menglin, Yuang and Suttie, 1996.

In the 1980s, the Animal Husbandry Bureau developed 25 000 ha of irrigated land for hay production on sandy-gravelly soils unsuited to arable cropping (Li, Yuang and Suttie, 1996). Project 2817 was assisted by the World Food Programme (WFP); work began in 1988, the scheme was in production by the end of the decade, and completed in 1995. One Project site was in Burjin County, others were in Fuhai and Altai City (see Figure 6.2).

Irrigated units of several hectares are managed by herders’ families; the herds follow their usual transhumance, but some of the family stay behind during summer to irrigate the crops and make hay. The settlers were provided with loans so that they could build houses as winter quarters; social services, including medical facilities and schools, have also been made available - facilities otherwise inaccessible to families with no fixed winter base. Sown forage for hay is the basis of cropping. Lucerne (Medicago sativa) is the main crop, rotated with wheat, maize, sunflower and soybean. The lucerne activities of the Project - selection for cold-resistance - are discussed in Chapter VII. Trees are a project component for shelter, windbreaks, timber and forage. The main trees are poplar (Populus spp.), willow (Salix spp.), Siberian elm (Ulmus pumila) and Russian olive (Elaeagnus angustifolia). The irrigated holdings are leased to households. Development of the scheme required a great deal of training, from senior technical staff to herders, who previously did not cultivate crops. The Burjin project area now has six primary schools, a clinic, twelve shops, a water and forestry management station and a breeding station. Four out of five villages have electricity. Some herders in villages without electricity have solar energy devices. Living and production conditions for herders have improved greatly, and a purely livestock economy has been turned into a diversified one.

The Burjin Project site is 30 km from town, between the Burjin and the Ertix rivers [places and geographical features often have several names in this region: the Ertix is also shown on maps as Irtich and Erqis - it flows into Kazakhstan and joins the Ob system, which drains to the Arctic Ocean]. Site altitude is 520 m; it is 16 km from south to north and 18 km from east to west, on mainly brown-calcium and sandy soil. The developed area is 16 667 ha. Irrigation is from the Burjin river and it drains to the Ertix. The annual average temperature is 4°C, with a short frost-free period (135 days). Winter is cold and long. It is windy all year round, with 40 very windy days above Force 8. Annual average precipitation is 120 mm.

Burjin borders Kazakhstan and Russia to the northwest and Mongolia to the northeast. It has six townships, one town and 59 administrative villages. Its population of 68 000 includes 19 ethnic groups. All Burjin’s 17 635 herders are Kazakhs, one of China’s ethnic minorities, who form 57 percent of Burjin’s population. They are Muslims who speak a Turkic language, and are the main ethnic group in neighbouring Kazakhstan; they are also present in Mongolia, especially in BayanÖlgii aimag, which borders Altai prefecture. They have moved into Xinjiang since the 1860s; traditionally they are perpetual, transhumant, nomads who live in circular felt tents on a collapsible frame - like the gers of the Mongols and similar to those of other Turkic herders, like the Kyrgyz. Because of their lifestyle, they neither cultivate crops nor keep poultry. Most continue with traditional transhumance: those of the Project have permanent housing and irrigated land for hay but when taking the herds to summer pasture they still use traditional tentage.

Stock rearing is Burjin’s major industry. The crop area is 19 800 ha, the area of grassland is 818 000 ha and the area of usable wasteland is 126 700 ha. There are two river systems, the Ertix and the Burjin, with an annual flow of 7.45 × 109 m3. Topography is varied: the highest elevation is 4 374 m while the county headquarters is at 479 m. Water resources are plentiful in some areas, whereas lower areas are almost desert. The main land types and their soils are summarized in Table 6.1.

The climate is continental; precipitation, mainly as snow, varies from under100 mm/year in the plains to over 600 mm in the high pastures. Cold waves, with high winds and snow, can cause heavy losses. In the mountains it is much colder; the higher pastures are open for less than three months. Stock rearing is based on transhumance of the traditional, vertical type. The division of grazing periods is: Spring - early April to end of June - about 90 days; Summer - end of June to late September - about 83 days; Autumn - mid-September to end of November - about 70 days; and Winter - about 121 days.

TABLE 6.1

Land types in Burjin County.

|

Type |

Area (km2) |

Percentage |

Soil |

|

Glacier |

704 |

6.68 |

Tundra soil |

|

Alpine and subalpine meadow grassland |

1 788 |

16.97 |

Alpine and subalpine meadow soils |

|

Coniferous forest-meadow grassland |

2 239 |

21.24 |

Grey forest soil, chernozem |

|

Forest |

702 |

6.66 |

Grey forest soil, chernozem |

|

Semi-dry grassland in hilly land |

1 482 |

14.06 |

Chestnut soil, brunisolic soil |

|

Semi-desert grassland on plains |

1 653 |

15.68 |

Brunisolic soil, meadow soil |

|

Plains forest |

71 |

0.67 |

Brunisolic soil, meadow soil |

|

Farm land |

216 |

2.05 |

Chestnut soil, brunisolic soil |

|

Desert |

333 |

3.16 |

|

|

South desert grassland |

1 231 |

11.68 |

Sandy soil, brunisolic soil |

|

Water |

93 |

0.88 |

|

|

Town and other land |

28 |

0.03 |

|

|

Total |

10 540 |

100.00 |

|

In 2000, the annual average temperature was 5.1°C, with a minimum of -37°C. The coldest period is late December and early January. The first snow was on 18 October; the last on 10 March. Snow depth was 117 cm. The frost-free period was 143 days, and annual sunshine was 2 721 hours.

There are four major vegetation zones:

alpine snow and rock, of little use for grazing; the snow line is at about 3 500 m;

summer grazing lands above 1 300 m provide rich grazing for 75 to 95 days per year. These are the fattening pastures and, in season, are capable of carrying more stock; they also have important forest resources;

spring and autumn pastures are transition routes and show serious signs of overgrazing. Due to lack of winter feed, herds linger on these pastures in autumn and go on to them too early in spring. The irrigated areas are in the drier, southern fringe of this zone; and

winter pastures (plains, desert, low meadows and marshland), which are inadequate for the number of stock carried. The provision of winter feed through irrigated haymaking was identified as the most effective way of improving the overall production system and reducing pressure on the winter and transitional pastures. Desert grazing is controlled by snowfall: if there is no snow as a source of drinking water livestock cannot use the zone; sudden thaws or deep snow can be disastrous.

Cattle, sheep, goats, horses and camels are all part of the production system. Sheep are the most important numerically, with cattle a close second. In terms of livestock units, however, sheep account for 30-40 percent, about the same as cattle.

This is a dual-purpose breed with both Central Asian and Mongolian blood. It is strong, with a thick hair coat. The main colours are bay and black. It is the main saddle and pack animal for herding and for draught in agricultural areas. It is capable of carrying heavy loads, working at least eight hours a day and travelling 40-50 km. The average liveweight of a mare is 328 kg, carcass weight 152 kg and dressingout percentage 37 percent. Breeding age for both sexes is three years. The main breeding season is May-June.

These are an old Xinjiang line of Yellow cattle. Because of widespread crossbreeding, they are now rare. The average liveweight of a bull is 365 kg and of a cow 274 kg. Their lactation period is 140-180 days at pasture and 240 days with supplementary feed. They are very hardy and disease resistant, and the basic breed for upgrading. Altai white-head cattle are another old breed of Yellow cattle, reared by Mongolian herders in Kumu township and found throughout the prefecture. Lactation at pasture is 150-200 days; average daily milk yield is 4.5-6.0 kg. Carcass weight at eighteen months is 138 kg and at three years, 286 kg. Xinjiang brown cattle are an improved breed, with some Brown Swiss, Alatau and Kesiteluomu blood. They are dual-purpose, medium-sized animals and account for 25 percent of the county’s cattle.

They are coarse-wool, dual-purpose, meat and fat, fat-tailed animals, which are good long-distance walkers in mountain terrain. An adult ram weighs 60 kg and an ewe 46 kg. They are shorn twice, in spring and autumn; wool yields are 2.6 kg per ram and 1.38 kg per ewe. The Altai fat-rump is a branch of the Kazakh sheep, with a characteristic body form and high yield of hair and fat. An adult ram weighs 93 kg and an ewe 68 kg. An eighteen-month wether has a liveweight of 50 kg with a carcass weight of 27.5 kg including the fat tail, which weighs 4.3 kg; they fatten well on summer pasture. They are sheared in spring and autumn, yielding 2 kg per ram and 1.5 kg per ewe. Altai fat-rump is the main breed of Burjin; fine-wool sheep account for 35 percent. Xinjiang fine-wool sheep were developed by introducing merino and other fine-wools. They are white-woolled, with a fleece yield of 4.5 kg and a staple length of about 10 cm. Adult, shorn rams weigh 94 kg and ewes 48.3 kg.

Local black goats produce high quality cashmere. Bactrian camels, which are kept as pack animals, also produce fine wool.

The government has for some time been acutely aware of the problems associated with the management of extensive grazing lands: in 1980 an act was passed whereby such lands would be allocated under a family responsibility system, making households responsible for the good management of the pasture allocated to them.

Natural pasture belongs to the state; government officers manage and allocate it. They contract with herders and provide them with grazing certificates. Herders own grazing rights, pasture protection rights and pasture improvement rights, valid for thirty years, so long as they manage their grazing correctly. They pay taxes according to the number of livestock owned. Allocation and registration is now complete for all Altai Prefecture. Natural grazing throughout the transhumance system, apart from stock routes, is allocated to family groups. Families are allocated land in each seasonal grazing zone. The system, dealing as it does with a transhumant system, is of necessity complex, but the population, traditionally used to complex systems, copes with it.

Transhumance routes are defined and may only be used for transit, not grazing. It is forbidden to keep stock on the route unless weather is very bad, when herds will be allowed to stay for one or two days. The moving schedule is arranged in advance; flocks move along the route household by household in an endless stream, at intervals of about 500 m.

The Herders Management Office, which is both an administrative and service organization, is responsible for organizing production activities and resolving major problems on summer pastures. Their responsibilities include: deciding on moving time; resolving pasture disputes; regulating pasture management; providing weather forecasts; livestock mating; control and treatment of animal disease; marketing livestock products; disseminating family planning information; protecting forests and providing fire control; organizing recreational activities; and receiving visitors. Scientific and technical training are organized by the government. Common livestock ailments are controlled and treated. Measures, such as dipping, quarantine and vaccination have been adopted. For breed improvement, herders are required to cull males not qualified as stud stock and introduce superior sires in their place.

In 1999, livestock products did not sell well and prices were low; prices of fatrump sheep and cattle improved slightly in 2000. September and October is the main season for selling stock, but prices are lower then. Only small numbers of livestock and products are sold locally; most are sent to larger markets, such as Urumqi and Kelamayi.

Nine herder households with irrigated land and settled winter bases were selected in the project area; these are referred to as the Treatment Group. There were three subgroups of three households each. For convenience, households of a subgroup lived close to one another. One subgroup was selected from each of three administrative villages of three townships.

According to the natural herding practice of nomadic groups, nine households were selected. Three households from one location formed a group. Study methods included interviews, field investigation and documentation.

The population breakdown of the group is shown in Table 6.2.

TABLE 6.2

Population of the Treatment

Group.

| |

Treatment Group |

Total |

Percentage |

|||||

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

||||||

|

Group size, comprising |

20 |

20 |

24 |

64 |

100 |

|||

| |

males |

10 |

9 |

11 |

30 |

47 |

||

|

females |

10 |

11 |

13 |

34 |

53 |

|||

|

of which, |

aged |

- |

1 |

- |

1 |

1.6 |

||

|

students |

9 |

6 |

11 |

26 |

40 |

|||

|

workers, |

7.5 |

9.5 |

10.0 |

27 |

42 |

|||

|

comprising |

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| |

crop workers and |

5.5 |

6.5 |

8.0 |

20.0 |

31 |

||

|

livestock workers |

2.0 |

3.0 |

2.0 |

7.0 |

11 |

|||

NOTES: Workers are both full and part time. Students are from school and university. Livestock workers go on transhumance; crop workers stay at settlement sites, they feed animals in winter.

With government assistance and loans, all settled and semi-settled herders in the project area have built permanent houses: some in brick and wood, others are earth and wood. The housing area per household is 90-180 m2; all have electricity and domestic electrical appliances. Livestock sheds include cattle sheds, sheep sheds, lamb sheds and plastic-film warm sheds. Some of them have built permanent warm sheds with brick, steel windows and glass. The advantages of these sheds are that:

they are warm inside in winter as there is plenty of sunshine. Milk yield of livestock is high;

they save fodder;

they reduce animal disease; and

they develop winter lamb and early spring lamb production.

Coal is generally used in winter - about five tonnes per household, and all households in the Treatment Group bought coal. Some still used wood and sheep dung for heating and cooking. The project settlement site is the base for herders; old people, children, women and the ill generally live there all year round. Settled families are busy from seed time to harvest, with the women working with the men. From 1 April to 30 September is the “golden season”, when they must work very hard to make money, have a good harvest and ensure livestock safety for winter and spring. Some workers stay at the site to manage crops, while others take the stock to the high pastures. Some families hire others to herd their stock. At the end of autumn and onset of winter, stock move back to the settlement and families are reunited. Some activities, such as slaughtering, visiting relatives and friends, betrothals, weddings and circumcision, take place in November and December, when herders and their families are together and have time and money from sale of livestock and agricultural products.

All households grew crops (Plate 30), with a total area of 69.1 ha: 7.7 ha per household on average and 1.08 ha per capita. The area of lucerne was the largest, at 31.7 ha, 45.8 percent of the total. Details of 1999 cropping are shown in Table 6.3. The 2000 cropping pattern was similar, but the soybean area increased and sunflower decreased.

TABLE 6.3

Cropping by the Treatment Group in

1999.

|

Crop |

Area (ha) |

Sowing date |

Grain yield (kg) |

Straw and hay (kg) |

||

|

Unit yield |

Total yield |

Unit yield |

Total yield |

|||

|

Wheat |

19.3 |

4-10 May |

3 073 |

593 089 |

1 459 |

28 159 |

|

Maize |

2.5 |

1-10 May |

4 410 |

11 025 |

18 520 |

46 300 |

|

Lucerne |

31.7 |

1 April-18 August |

- |

- |

3 815 |

120 396 |

|

Soybean |

7.1 |

2-28 May |

2 077 |

14 747 |

1 554 |

11 033 |

|

Sunflower |

8.3 |

5-28 May |

813 |

6 748 |

747 |

6 200 |

|

Vegetables |

0.2 |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

|

Total |

69.1 |

- |

- |

625 609 |

- |

- |

Lucerne yields were very low, the potential is much higher. At the outset of Project 2817, large-scale pilot plantings were developed, on farmers’ fields, for demonstration and training. When the project was evaluated by WFP in 1991, these pilot farms had hay yields (Plate 31) of 5-8 tonne/ha or greater. The reasons for low yields are lack of maintenance fertilizer, infestation with dodder (Cuscuta sp.) and poor husbandry, especially faulty land levelling. Herders are unwilling to invest inputs for a “grass” which they consider should grow naturally. Much training has been carried out and a series of fertilizer demonstrations during the 1990s showed that phosphate has a highly positive effect, but still herders refuse to take proper care of their lucerne. They do, however, buy fertilizer for their other field crops. Another promising fodder crop is Lotus corniculatus (Plate 32).

Households also planted trees; about 18 090 on 6.7 ha. Leaves and twigs are fed to stock. The yield of leaves and twigs was 54 tonne, or 3 kg/tree on average.

Plate 30. Altai crops include maize, which is grown on irrigated land and used for silage.

Plate 31. Haymaking in Altai from a thin crop of lucerne on irrigated land.

Plate 32. Lotus corniculatus is a promising fodder crop for poorer soils. Forage diversification trials in Altai; plot of Astragalus adsurgens in background.

TABLE 6.4A

Livestock of the Treatment Group in 1999

(head).

|

Species |

Number at start of year |

Fate |

Number at year end |

|||

|

Total |

of which females |

Weaned offspring |

Killed for home use |

Sold |

||

|

Cattle |

126 |

61 |

34 |

14 |

25 |

121 |

|

Horses |

68 |

19 |

11 |

|

2 |

74 |

|

Camels |

24 |

10 |

1 |

- |

- |

25 |

|

Sheep |

834 |

714 |

667 |

89 |

460 |

952 |

|

Goats |

62 |

29 |

27 |

5 |

1 |

83 |

|

Total |

1 114 |

836 |

740 |

111 |

488 |

1 255 |

TABLE 6.4B

Livestock of the Treatment Group in 2000

(head).

|

Species |

Number at start of year |

Fate |

Number at year end |

|||

|

Total |

of which females |

Weaned offspring |

Killed for home use |

Sold |

||

|

Cattle |

121 |

47 |

45 |

11 |

34 |

136 |

|

Horses |

74 |

13 |

10 |

2 |

12 |

74 |

|

Camels |

25 |

4 |

4 |

- |

1 |

24 |

|

Sheep |

952 |

637 |

634 |

119 |

408 |

1 055 |

|

Goats |

83 |

37 |

40 |

14 |

13 |

99 |

|

Total |

1 255 |

736 |

733 |

146 |

468 |

1 388 |

Livestock numbers and the time spent in the project area in winter vary. Herders retain some winter pasture and decide how many livestock it can support and how long they should stay, according to the weather, forage availability and the state of the herbage. Situations differ from household to household. Generally stock graze first, then move to the project area when it is cold, or before lambing. Herders with winter pasture move stock into the project area in December or January, and leave about 20 April, staying about 120 days. Some herders feed cattle and horses in the project area in winter, but herd their sheep and camels at pasture. The livestock holdings of the Group are shown in Tables 6.4a and 6.4b.

For overwintering, herders calculate stock numbers according to their experience and available fodder. About 50 m3 of fodder per household should be left in a good year. Livestock must graze if fodder is insufficient in a bad year. By the end of 1999, the nine households had 1 255 head, and total daily hay consumption was 3 904 kg. The yield of lucerne, straw, tree leaves (Plate 33) and other forage was 370 612 kg, enough to feed 1 255 livestock for 95 days. So stock fed in the project area for 80 percent of winter. The principle is grazing first, then supplementation and feeding in sheds when it is impossible to graze. When stock are stall-fed, fodder is crushed and fed in troughs. Feeding priority is sheep and horses, then cattle; camels usually graze and browse.

FIGURE 6.3. Livestock movements and pasture utilization by the treatment group in 1998/99.

Source: Map reproduced from Xinjiang Animal Husbandry Bureau, 2001.

Livestock movements and pasture use in 1998-1999 (see map, Figure 6.3), were:

Stock grazed at Shawur Mountain and Qian Mountain in the project area from 1 December 1998 to 31 March 1999 (120 days) and moved four times.

They moved from Shawuer Mountain to spring pasture between 1 April and 15 May (45 days) and moved four times.

They were at spring pasture (Tuohenyekekaile and Kekeke) from 16 May to 20 June (35 days) and moved four times.

They were at summer pasture (Sumudayierke, Kekejiaote and Baziher) from 21 June to 11 September (80 days) and moved five times.

They were on autumn pasture (Alasu, Kekeke and Tuohenyekekaile) from 11 September to 10 October (30 days) and moved four times.

Winter pasture was at Kuosidake and the WFP Project 2817 area from 11 October to 30 November (50 days) and moved four times.

The total annual transhumance was 500 km and livestock were moved 25 times. Five of the nine households asked others to herd livestock for them and remained in the project area to do farm work.

Burjin has a large area of pasture, but the areas for different seasons are not in balance. At summer pasture, grass quality is high with a variety of species and high yield, but can be used for only 80-90 days. Salt is fed to livestock on the summer pasture to supplement mineral matter and increase feed intake. Spring and autumn pastures are poor, with sparse desert vegetation, but livestock must stay there for 150-160 days. Winter pasture is very poor yet stock stay there for 120 days. Forage is plentiful in summer, scarce in spring and autumn and seriously lacking in winter.

Plate 33. Riparian willow and poplar forest along the Ertix provides valuable winter grazing.

In 1998-1999, spring and summer rainfall was less than usual and locusts caused serious damage to the natural pastures, but in the project area it was worst on spring and autumn pasture; 500 locusts/m2 at most and at least 20-50 locusts/m2. A plague of Italian locust (Calliptamus italicus) appeared in April and was most serious in May; it covered 400 km2 and was serious over 300 km2. During the 80 days from October to the end of 2000, there was snow for more than 60 days; the depth of snow was 117 cm and the lowest temperature was -37°C. Traffic was stopped throughout the Prefecture. Such snow had not been seen for 50 years.

The winter pastures are at Salebur Mountain, Shawur Mountain and the mountain valley of Kukexun. Sawur Mountain is in Hefeng County, Tacheng Prefecture, where, because of extreme shortage of winter pasture in home areas, Burjin has grazing rights. The elevation of winter pasture is 800-1 900 m, and is cold in winter and cool in summer. The annual average temperature is 3.6°C; it is coldest in January, with an average temperature of - 12°C. Annual precipitation is 200-300 mm, annual evaporation is 2 300-2 400 mm; the frost free period is about 105 days. The period of snow cover is 180 days (October to March). Snow depth in the study period was 13 cm, but is usually less than 10 cm. The productivity of winter pasture is poor, yielding 800 kg/ha fresh weight.

Water is scarce: people and stock drink melted snow. The weather was unusual in 1999; snow was 20 days later than usual, so people and livestock could not move to winter pasture, which put pressure on the autumn pasture.

The main species in pastures with an elevation of 1 200-1 900 m include Festuca ovina, Stipa pillata, Agropyron cristatum, Cleistogenes squarrosa, Carex liparocarpos and Artemisia frigida. The main species on desert and semi-desert pasture include Stipa glareosa, S. sareptana, Cleistogenes squarrosa, Agropyron desertorum, Allium polyrrhizum, Seriphidium gracilescens, Nanophyton erinaceum, Anabasis spp. and Ceratoides lenensis.

The winter pasture is used from December to March (3-4 months). Up to half of Burjin’s winter pasture is also used by neighbouring counties. Salebur Mountain is the winter pasture of Burjin County, and the spring and autumn pasture of Hefeng County; the plains around the Shawur Mountain are the winter pasture of Burjin County and the summer pasture of Hefeng County.

TABLE 6.5

Pasture utilization by the Treatment

Group.

|

Pasture type |

Area (ha) |

Unit yield (kg) |

Total yield (kg) |

Period of use |

Grazing days |

Stocking rate (SSE(1)) |

|

|

Theoretical |

Actual |

||||||

|

Winter |

445 |

844 |

375 580 |

1 Dec.-31 Jan. |

62 |

3 575 |

1 700 |

| |

|

|

1 Feb.-31 Mar. |

59 |

|

|

|

|

Spring-Autumn |

722 |

1 860 |

1 343 920 |

1 Apr.-20 June |

81 |

4 796 |

2 221 |

| |

|

|

12 Sep.-30 Nov. |

80 |

|

|

|

|

Summer |

275 |

2 837 |

780 175 |

21 June-11 Sep. |

83 |

5 573 |

2 221 |

|

Total |

1 442 |

|

2 499 675 |

|

365 |

|

|

NOTES: (1) SSE = Standard Sheep Equivalent.

Livestock move to spring pasture at the end of March and in early April, when snow is melting on the winter pasture. With the snow melting from plain to upland, livestock are moved to summer pasture and arrive there in mid-June when grass is growing and the climate is cool, without flies and mosquitoes.

Winter pastures are close to townships and villages, within easy travelling distance (10-30 km). The area between Yushikershi and Erqis used as the spring and autumn pasture for the group requires a journey of 80 km.

Spring and autumn pastures are in the Ertix valley in front of the Altai Range and its foothills, between 490 m and 1 400 m. The yield of fresh grass is about 1 200 kg/ha. The rainfall is about 110 mm, evaporation is very high, and sunshine is full. With increasing altitude the vegetation changes from plains lowland meadow, to plains gravel desert, and to plains sandy desert.

The vegetation of spring and autumn pasture is open, with a simple structure and much bare ground. Xerophilous dwarf shrubs predominate, such as Anabasis spp., Salsola collinna, Suaeda glauca, Reaumuria soongarica, Seriphidium terrae-albae, Kochia prostrata, Agropyron monglicum, Ceratocarpus arenarius, Artemisia arenaria and Leymus secalinus. The vegetation cover is 20-40 percent.

Shearing is in May, and the animals are moved to summer pasture in June (Plate 34). Spring and autumn pasture is plains or hilly land, close to towns or villages, which is convenient for herders. Autumn pasture is at 800-1 400 m. Rainfall exceeds 200 mm, but evaporation is ten times the precipitation.

Plate 34. Horses of a family group moving to Altai top summer pastures.

Plate 35. Altai - front summer pastures, with camps in the valley.

Plate 36. The back summer pastures in Altai. These mountain areas have only a short growing season, but are highly productive. Lake Hanas in the foreground.

Summer pastures - in the mid-alpine zone and alpine zone, at 1 800-3 200 m - are under snow for about 270 days (September to May). Annual precipitation is about 600 mm, plant height is 15-60 cm, and vegetation cover is 80-90 percent. The yield of fresh forage is 1 500-4 000 kg/ha. There are two kinds of summer pasture, according to climatic condition and their season of use.

Front summer pasture is used from mid-June to mid-July (Plate 35). The temperature in the alpine zone (above 2 300 m) is low, snow melt is late and vegetation growth is slow, so flocks graze the mid-alpine (front) zone between 1 400-2 300 m.

Back summer pasture From mid-July to mid-August, as temperatures rise, the herds move to the alpine (back) zone (Plate 36). In mid- to late August, temperature in the alpine zone starts to fall and it snows as well; herders return to the front summer pasture.

The weather in the front summer pasture is mild and delightful; most herders and families stay there (Plate 37). Many activities take place: shearing, dipping, livestock counts, tax paying and making dairy products (red sweet cheese, white sweet cheese and sour cheese) (Plate 38). There are recreational activities, such as Aken singing parties, horse races, sheep catching and other social activities. There are posts where skins and wool can be sold, and shops where herders can buy daily necessities. In autumn, when flocks return from the back summer pasture, traders arrive and livestock trading begins.

Plate 37. A Kazakh family in their ger on summer pastures in Altai.

Plate 38. Drying curd on summer pastures.

Plate 39. High pastures for grazing and valley areas for haymaking. Near Lake Hanas, Altai.

Rainfall in the front summer pasture may amount to 600 mm. There are large areas of forest, mainly Larix and Picea. The soils are meadow soil and paramo soil, which is rich in organic matter and fertile. The main pasture plants are Festuca sulcata, Poa annua, Phleum phleoides, Stipa pennata, Helictotrichon hookeri subsp. schellianum, Bromus inermis, Achillea millefolium, Galium verum, Polygonum alpinum, Phlomis alpina, Dracocephalum ruyschiana, Medicago falcata, Vicia sepium, Fragaria vesca, Spiraea media and Rosa oxyacanta. Plant height is 20-30 cm and vegetation cover is 80-90 percent. The yield of fresh forage is 3 400-4 500 kg/ha, and some hay may be made (Plate 39).

The back summer pasture, above 2 300 m, is in the alpine zone; plants are low-growing, plant structure is simple and the growth period short. Annual precipitation is about 400 m. The annual average temperature is below 0°. The soil is alpine meadow soil. The main plants are bunch type dwarf grasses and associated forbs: Festuca kurtschumica, F. kryloviana, Poa alpina, Anthoxanthum alpinum, Ptilagrostis mongolica, Carex stenocarpa, Carex melanantha, Kobresia bellardii, Polygonum viviparum, Alchemilla bungei, Ranunculus japonicus, Gentiana algida, Thalictrum alpinum and Potentilla gelida. Plant height is 10-15 m and the vegetation cover is 80-90 percent. The yield of fresh forage is 2 300-3 200 g/ ha. The climate of the summer pasture is cool, with an excellent environment and beautiful scenery. There are no schools or hospitals, but doctors and veterinarians move from household to household and are welcomed and respected.

The nine households comprised 61 people (31 males and 30 females). There were 35 workers (20 male and 15 female). Of the 61 people, the education levels were 5 above senior school, 23 middle school, and 13 primary school.

They have only their allocated pastures and must feed their herds on natural grazing throughout the year, using their herding skills to have stock fat enough in autumn to survive through winter and early spring. The area of pasture allocated to the nine households was 1 245.8 ha. The general situation is described in the following paragraphs, and the pattern of natural pasture use is summarized in Table 6.6.

TABLE 6.6

The pastures of the Control

Group.

|

Pasture type |

Area (ha) |

Season of use |

Days grazed |

Yield of green matter |

Number of livestock |

|

|

Unit (kg/ha) |

Total (kg) |

|||||

|

Winter |

469.1 |

1 Dec.-15 Mar. |

105 |

899 |

421 720 |

1 249 |

|

Spring and Autumn |

388.3 |

16 Mar.-1 July |

105 80 |

2 790 |

1 083 357 |

1 527 |

| |

13 Sep.-30 Nov. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Summer |

388.4 |

2 July-12 Sep. |

70 |

3 060 |

1 188 504 |

1 644 |

|

Total |

1245.8 |

|

365 |

|

2 262 274 |

1 721 |

FIGURE 6.4. Map of the traditional transhumance routes of Burjin, northwest China.

Source: Map reproduced from Xinjiang Animal Husbandry Bureau, 2001.

Winter pasture This is in Hasenhamur and Shawur regions, 100 km from Burjin at 460 m; annual precipitation is 206 mm. The frost-free period is 101 days and the annual average temperature is 3.6°C. The main vegetation is Stipa pillata and Carex spp. Plagues of locusts and mice often occur in this area. The vegetation cover is 60 percent, with a unit yield of 899 kg/ha. There are no schools or houses; women, children and old people live in a village in winter. Strong herders tend flocks in winter. Necessities have to be bought from town, 100 km away. Sheep and cattle manure is used as fuel. Life on the winter pasture is hard.

Spring pasture is at Jialipahetasi and Kekebai, 40 km from Burjin, at 550 m. The frost-free period is 153 days. Annual rainfall is 119 mm, with snow cover for 120 days, the depth of snow averages 20 cm. The average annual temperature is 4.1°C. The vegetation cover is 40-50 percent, with a yield of 730 kg/ha. Wild animals include wolves, foxes and rabbits. This is the lambing pasture, where flocks stay for 50 days in spring.

Spring and autumn pastures are in the region of Ahonggaiti, 90 km from Burjin, at 1 370 m. Annual precipitation is 289 mm, with 142 frost-free days. The average annual temperature is 2.7°C. The depth of snow is 60 cm, with a covered period of 140 days. The soil is chernozem; pasture is upland meadow. The vegetation cover is 90 percent with a yield of 2 790 kg/ha. Wild animals include wolves, foxes, marmots, squirrels and rabbits. Herders get drinking water from mountain springs or streams. Dung or branches are used as fuel. Herder children can go to primary school at the pastures, and to middle school at the township. There are mobile medical services for people and animals. Flour, food and daily necessities can be bought from a mobile shop. Ahonggaiti and Haliutan are the main places for recreational activities and festivals in spring and autumn. This area is also a trading site.

Yegamaiti summer pasture is 150 km from Burjin, at 2 300 m, beside the famous Hanas Lake. It is upland meadow on soil rich in organic matter. This is the largest summer pasture in the county; parts are mown for hay (Plate 39), with a yield of 3 060 kg/ha. The precipitation is 600 mm, the average annual temperature is -3.7°C and the frost-free period is 100 days. Snow depth averages about 150 cm, laying for 180 days. There are large areas of original forest, mainly coniferous, on the shady slopes. There are many wild animals, including brown bears, snow leopards, wolves, foxes, snow chicken, deer, wild duck and squirrels.

The routes of the transhumance cycle are shown on the map (see Figure 6.4).

Moving times and distances

The distance from Shawur (Zhaya) winter pasture to Yemaigaiti summer pasture is 320 km (240 km by road), with 16 moves of about 20 km each. Times and distances are similar when the flocks return. Flocks moved 33 times in a 640-km journey. Horses, camels, cattle and carts are used for transport. In 2000, the movement times of the three Groups were similar. Group 1 moved 26 times, spending 41 days on the move. Group 2 moved 25 times, spending 37 days on the move, and Group 3 moved 27 times, taking 42 days.

Moving from Winter to Summer Pasture

In 1999, herders left Hasenhamur on 15 March and arrived at Biesikuola on the first day, Muhurtai on the second, Narenkala on the third, Kekexun on the fourth, Artuobieke on the fifth, Sharhong on the sixth and Aketuobieke on the seventh day, having moved seven times in seven days (15-22 March). They stayed at Aketuobieke for 8 days, then moved to Kekebai spring pasture (1 day) and stayed for 50 days (1 April-20 May). Their ninth stop was Yeliuman (1 day). They took one day to reach the tenth stop: Haliutan and Ahonggai, then stayed there for 30 days (22 May-22 June, with spring shearing). They took one day each to move to Tielishahan (the eleventh stop), to Jiadengyu (the twelfth stop), Kexitubieke (the thirteenth stop), Ashibashi (the fourteenth stop), Kadinger (the fifteenth stop) and finally to Yemaigaiti summer pasture, where they grazed for 70 days (2 July-12 September). When they left on 12 September they had grazed for 177 days.

Moving from Summer to Winter Pasture

The return started on 13 September; the first six one-day stops were at Kadinger, Ashibashi, Kexituobieke (a day), the fourth stop was Jiadengyu (a day), the fifth stop was Tielieshahan and then Halahongai, where they stayed for 20 days (19 September-9 October). The seventh stop was Ahongai and Haliutan (20 days - 10-30 October). The eighth stop was Yeliuman (a day), and the ninth was Kekebai (one day), where they stayed for 18 days (2-20 November). The tenth move was to Aketubieke (a day), with a three-day stay, then a move to Sharhong on 24 November. The twelfth to sixteenth stops of one day each were at Artuobie, Kekexun, Narenkala, Muhurtai, and Biesikuola. Flocks arrived at Zhaya winter pasture on 1 December and remained till 15 March (183 days).

Plate 40. Moving gear to the summer pastures, Altai. Bulls are widely used as pack animals.

Moving from Winter to Spring Pasture, then to Summer from Spring Pasture

In 2000, herders started to move from the regions of Hasenhamur and Sawur on 15 March. They moved seven times in seven days (15-22 March). They stayed at Aketubieke for 8 days, then moved to Kekebai spring pasture and stayed there for 50 days (1 April-20 May). Nomadic herders cannot produce lambs in late winter or early spring because of lack of feed and hay, so lambing is timed for late spring, with lamb sales in the autumn, but usually in the following year. There is a simple lambing shed for each household. Herders always take a bag with them when they graze sheep in the day so as to put lambs in as soon as they are born. The ninth stop was Yeliuman (21 May) and the tenth stop was Hailiutan and Ahongaiti, where they remained for 30 days (22 May-22 June). The eleventh stop was Tielieshahan (started on 23 June), the twelfth stop was Jiadengyu, the thirteenth stop was Kexituobieke, the fourteenth stop was Ashibashi, the fifteenth stop was Kadinger, the sixteenth stop (the last stop) was Yemaigaiti summer pasture (Plate 40), where they grazed for 70-80 days (2 July to 12-20 September). From 15 March to 12 September was 177 days in total.

Moving from Summer to Winter Pasture

Moving started on 13 September, taking six one-day stages: Kadinger - Ashibashi Kexituobieke - Jiadengyu - Tielieshahan - Halahongai, where they stayed for 20 days (19 September - 9 October). The seventh stop was Ahongai (one day) and Haliutan, where they stayed for 20 days (10-30 October). This period is generally the best period for livestock selling. Herders will sell lambs that were born around 15 April in the year and with an age of 6-7 months.

The liveweight of lambs is about 35-45 kg and the carcass weight is about 17-22 kg. From 1 November, the eighth and ninth stops were Yeliuman and Kekebai (one day each), staying at Kekebai for 18 days (2-20 November). The tenth stop was Aketubieke (one day), with a three-day stay, then a move to Sharhong on 24 November. The twelfth to sixteenth stops (each one-day moves) were Artubieke, Kekexun, Narenkala, Muhurtai and Biesikuola. Finally, on 1 December, flocks were moved to the seventeenth stop: Zhaya winter pasture.

The livestock numbers of the group for the two seasons are given in Tables 6.7a and 6.7b.

While the Treatment Group had slightly more stock than the Control, the differences were not large. Since the project began over a decade ago, this would seem to indicate that the Treatment Group is not intent on increasing numbers but may be more interested in maximizing offtake (Tables 6.4a,b and 6.7a,b). The Treatment Group sold more stock than the Control. The two most important sales were: cattle - Treatment Group, 20 percent (1999) and 28 percent (2000); Control Group, 16.5 percent (1999) and 22 percent (2000); sheep - Treatment Group, 55 percent (1999) and 43 percent (2000); and Control Group, 40 percent (1999) and 44 percent (2000). These are not great differences, apart from sheep in 1999. As noted below, the main difference is that the Treatment Group can sell more of their lambs in the first year, and at a greater weight.

TABLE 6.7A

Livestock of the Control Group in 1999

(head).

|

Species |

Number at start of year |

Fate |

Total number at year end |

|||

|

Total |

Females |

Weaned offspring |

Killed for home use |

Sold |

||

|

Cattle |

121 |

57 |

51 |

8 |

20 |

144 |

|

Horses |

74 |

19 |

11 |

5 |

4 |

76 |

|

Camels |

26 |

12 |

7 |

- |

1 |

32 |

|

Sheep |

670 |

459 |

452 |

64 |

269 |

789 |

|

Goats |

108 |

66 |

64 |

27 |

16 |

129 |

|

Total |

999 |

613 |

585 |

104 |

310 |

1 170 |

TABLE 6.7B

Livestock of the Control Group in 2000

(head).

|

Species |

Number at start of year |

Fate |

Total number at year end |

|||

|

Total |

Females |

Weaned offspring |

Killed for home use |

Sold |

||

|

Cattle |

144 |

49 |

46 |

7 |

32 |

153 |

|

Horses |

76 |

12 |

12 |

4 |

3 |

70 |

|

Camels |

32 |

1 |

1 |

- |

- |

24 |

|

Sheep |

789 |

501 |

494 |

90 |

346 |

735 |

|

Goats |

129 |

90 |

94 |

28 |

37 |

155 |

|

Total |

1 170 |

653 |

647 |

129 |

418 |

1 127 |

The agricultural incomes from livestock and crops and the associated production expenses of the two groups are summarized in Tables 6.8 and 6.9.

The Treatment Group, with crops and livestock, had, of course, a far higher income than the Control, but they had a considerably higher income from livestock in both years although herd numbers were not very different (compare Tables 6.4a,b and 6.7a,b). The Treatment Group’s livestock income exceeded that of the Control by 60 percent in 1999 and 65 percent in 2000. This was mainly due to a much greater sale of sheep, presumably because they were able to get lambs to saleable weight in autumn, whereas the Control Group had to keep them for a second year. The stock of the Treatment Group were on average heavier than those of the Control (Table 6.10). A five-year survey on winter sheep weight, 1989-1993, showed that sheep in the project area gained 5-6 kg during winter. Sheep on natural pasture lost 1.2-1.5 kg each during winter. In addition, the sheep in the project area were mated in August-September and lambed in February; their average slaughter weight by the end of September was 45 kg and the heaviest reached 65 kg. Control sheep were mated at the beginning of November and lambed in April-May; their slaughter weight was 30-34 kg by the end of September.

The Treatment Group earned more from crops than it did from livestock. The crop component was 55 percent of their total in 1999 and 60 percent in 2000.

The production costs of the groups also differed greatly (Table 6.9). The Treatment Group expended far more on livestock production, notably in herding labour, electricity and water, and fodder; 570 percent of the Control costs in 1999 and 258 percent in 2000. In 2000, the Control Group bought more fodder and had higher unspecified production costs.

TABLE 6.8

Agricultural income of both study groups

(RMB).

| |

Control Group |

Treatment Group |

||

|

1999 |

2000 |

1999 |

2000 |

|

|

Livestock Sales |

98 642 |

133 680 |

126 150 |

170 950 |

|

Milk |

1 900 |

33 800 |

22 176 |

23 260 |

|

Skins |

- |

6 340 |

620 |

3 050 |

|

Wool |

- |

10 155 |

11 778 |

3 250 |

|

Subtotal Livestock |

100 542 |

183 975 |

160 724 |

200 510 |

|

Other |

57 058 |

10 950 |

9 900 |

33 180 |

|

Crop sales |

- |

- |

61 584 |

126 464 |

|

Fodder |

- |

- |

47 860 |

129 469 |

|

Straw |

- |

- |

29 059 |

- |

|

Machinery hire |

- |

- |

45 200 |

10 500 |

|

Total |

157 600 |

194 925 |

354 327 |

500 123 |

|

Per household |

17 511 |

21 658 |

39 370 |

55 569 |

TABLE 6.9

Production expenses of both study groups

(RMB).

|

Item |

Control Group |

Treatment Group |

||

|

1999 |

2000 |

1999 |

2000 |

|

|

Moving and transport |

2 120 |

7 850 |

3 700 |

700 |

|

Herding by others |

970 |

5 000 |

11 868 |

17 228 |

|

Animal health |

5 420 |

5 338 |

4 024 |

7 851 |

|

Salt |

980 |

870 |

1 276 |

2 730 |

|

Pasture fee |

1 358 |

1 564 |

631 |

1 030 |

|

Fodder |

2 860 |

10 500 |

71 887 |

86 202 |

|

Other |

3 320 |

16 740 |

100 |

370 |

|

Water and electricity |

2 799 |

2 144 |

19 668 |

14 780 |

|

Construction |

1 650 |

- |

7 130 |

3 000 |

|

Machinery and tools |

- |

2 180 |

2 200 |

1 060 |

|

Subtotal livestock and general |

21 477 |

52 186 |

122 484 |

134 951 |

|

Ploughing and harvesting |

- |

- |

22 197 |

22 040 |

|

Fertilizer and pesticides |

- |

- |

27 349 |

21 997 |

|

Seed |

- |

- |

21 193 |

12 969 |

|

Total |

21 477 |

52 186 |

193 223 |

191 957 |

TABLE 6.10

Slaughter weight of livestock

(kg).

|

|

Treatment Group |

Control Group |

|

Male cattle |

280 |

270 |

|

Female cattle |

270 |

260 |

|

Fat rump - two-year-old |

60 |

50 |

|

Fat rump lamb |

45 |

30 |

|

Goats |

35 |

32 |

|

Horse |

380 |

380 |

The net agricultural incomes (Table 6.11) of the Groups were, of course, markedly different - that of the Treatment Group being roughly twice that of the Control.

TABLE 6.11

Per capita income of both study groups

(RMB).

| |

Control |

Treatment |

||

|

1999 |

2000 |

1999 |

2000 |

|

|

Total income |

157 600 |

194 925 |

354 327 |

500 123 |

|

Number of persons |

61 |

59 |

59 |

61 |

|

Per capita income |

2 583 |

3 303 |

6 005 |

8 198 |

|

Income per household |

17 511 |

21 658 |

39 369 |

55 569 |

Household expenditure (Table 6.12) reflects the differences in income, and perhaps also access to goods. The Control Group, however, expended a greater proportion of its net income on household needs than did the Treatment Group.

All households of the Treatment Group have acquired fixed assets of two types: productive and non-productive. Productive fixed assets are land, agricultural machinery, tractors, grass harvesting machines, rakes, sprayers, greenhouses, sheds, etc. Nonproductive fixed assets consist of houses, furniture, family electrical equipment, motorcycles, etc. There are almost no fixed assets in the control households; all of their belongings have to be carried on the back of camels throughout the year. Economic state decides living standards. Herder life in the Treatment Group is improving, but there is little change in that of the control.

The development objective of Project 2817 was “To improve the income and living conditions of nomadic herders through increased forage production and settlement, at the same time retaining the transhumant system of grazing.” This it certainly has done. Selected herding families have been settled and are obviously thriving; their herds continue to use natural pastures according to the transhumant system, but also benefit from increased availability of winter feed and shelter. The feed production component, however, is disappointing since yields are less than onethird of their potential; the crop component in contrast is now the source of more than half the household agricultural income. These improvements in feed and shelter have allowed lambs to be marketed at a far earlier age than previously - that and reduction of grazing in winter should have reduced pressure on the grazing lands, but it is not clear whether this has had much effect since there is a far larger number of non-scheme stock in the area. The benefits of fixed, well constructed housing with access to social and other facilities is obvious, and will probably have an even more marked effect on the Treatment Group in the long term.

TABLE 6.12

Household expenses of both study groups

(RMB).

|

Item |

Control Group |

Treatment Group |

||

|

1999 |

2000 |

1999 |

2000 |

|

|

Food and basic commodities |

52 183 |

51 468 |

89 299 |

133 510 |

|

Clothing |

17 900 |

17 000 |

29 500 |

28 040 |

|

Marriages and funerals |

14 000 |

11 200 |

15 100 |

26 250 |

|

Tuition |

15 496 |

8 440 |

26 650 |

20 300 |

|

Medical |

5 630 |

9 650 |

17 270 |

4 460 |

|

Various fees |

- |

8 036 |

- |

5 860 |

|

Fuel |

- |

- |

- |

6 570 |

|

Building and repair |

13 060 |

- |

18 580 |

- |

|

Other |

10 200 |

5 986 |

1 052 |

2 240 |

|

Total |

128 469 |

111 780 |

197 451 |

227 230 |

|

Expenses per household |

14 274 |

12 420 |

21 939 |

25 248 |

|

Expenses as proportion of net income |

67% |

43% |

35% |

32% |

This is an imaginative use of available irrigation water and of land too light for sustained annual cropping. Almost all the available area in Altai has now been developed. Whether the model can be replicated elsewhere under similar conditions is not known. A considerable investment per household has been made, but no information is available on how that compares to the increased incomes of project households.