Summary

Sheep are reared across a wide range of agro-ecosystems in Bhutan. A sample survey was conducted to characterise indigenous sheep breeds and husbandry practices. Information was recorded on morphological characteristics, body measurements and management variables. Based on geographical locations, four distinct native sheep types are described: Jakar, Sipsu, Sakten and Sarpang. This paper also describes the socio-economic importance of sheep, its trends and future prospects of sheep farming in Bhutan.

Résumé

Au Bhutan les brebis sont élevées dans de nombreux écosystèmes. Une enquête a été menée pour caractériser les races ovines locales ainsi que les formes de conduites. Les informations recueillies portaient sur les caractéristiques morphologiques, les mesures corporelles et les variables des formes de conduites. Sur la base de zones géographiques, on décrit quatre types de brebis locales: Jakar, Sipsu, Sakten et Sarpang. Cet article décrit aussi l’importance socioéconomique, la tendance et les prospectives futures de l’élevage ovin au Bhutan.

Keywords: Native sheep, Bhutan, Production systems, Phenotype.

Introduction

Domestic sheep play a vital role in the home-based small-scale industries in Bhutan. They are kept mainly for wool and manure. Their roles for meat purpose are limited to a few districts in the south. The sheep are reared across the wide range of environment from subtropical areas in the south to temperatealpine areas in the north. Given, the range of production systems, different local sheep types that are well adapted to the harsh and rugged environment of Bhutan are noticeable.

Several authors have attempted to describe the Bhutanese sheep types (Tripathi, 1963; MoD-AHD, 1975). However, the earlier studies were not comprehensive and conclusive information on local sheep types is lacking. Characterisation of indigenous sheep genetic resources and management systems are essential for planning national domestic animal diversity conservation plans (www. fao.org/dad-is).

Therefore, a sample survey was conducted covering major sheep rearing areas to record characteristics of different sheep types and to describe traditional sheep husbandry practices.

Materials and methods

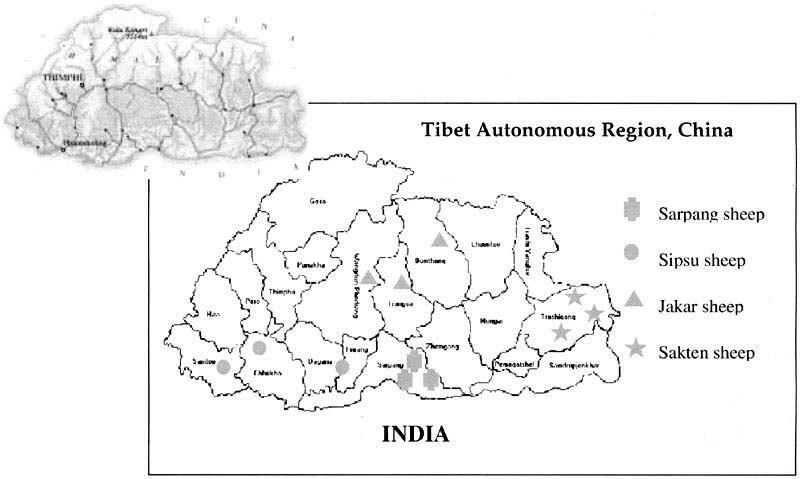

As part of this study, a comprehensive literature review focusing on the origins of present-day Bhutanese sheep was undertaken. In addition, extensive breed surveys were conducted. The study areas were selected based on priority sheep rearing areas, influence of crossbreeding and known existence of indigenous breeds (Figure 1). Within each locality, households were randomly selected. Information was collected using formal questionnaires and informal discussion with key informants, principally the elderly members of households. In total, 189 households were covered in the study areas with an average of 20 to 30 households per district. Secondary data on population statistics were obtained from district livestock offices. Animals of both sexes were measured using a standard measuring tape. Variables measured included:

Qualitative characteristics: sex, coat colour pattern, coat type, horn shape and orientation, head profile, ear form

Quantitative characteristics: body length, chest girth, height at withers, paunch girth, cannon circumference, ear-length, horn length, horn circumference, tail length, face length, face width

Other variables: lambing history, twinning, origin of animal, breeding practices, management variables, utility of sheep

Figure. 1. Map of Bhutan showing study locations of different sheep populations.

Results and Discussion

Origin of Bhutanese sheep

Asian domestic sheep are considered descendent of wild sheep argali (Ryder, 1984). The wild sheep (Blue sheep or Burrhel) are still found in large numbers above 3 500 m in Bhutan. The indigenous sheep in the Himalayas foothill countries mostly belong to thin-tailed carpet wooled breeds. For instance, the sheep in Nepal are long- and thin-tailed (except the Kagi breed which is short-tailed) while those of Tibet Autonomous Region (China) are short and thin-tailed with hairy medium fleece (Ryder, 1984).

Information on the origin of sheep in Bhutan is scanty. However, for sheep in Merak-Sakten (east Bhutan), the oral history seems to trace their origin to Tsona in south east Tibet. It was stated that the present day residents of Merak-Sakten (special pastoral group still with distinct dress and language) migrated with their yak and sheep to avoid the wrath of their local ruler. The time of their migration could be dated to the 7th century during the era of the famous Tibetan king Songtsen Gampo (Wangmo, undated).

In the Black mountain ranges of central Bhutan, local people refer to Tibet as a source of their sheep. In Tsirang, shepherds describe their indigenous sheep as Bonpala and Garpapla, which is the same nomenclature used for indigenous sheep in Sikkim (Vij et al., 1997). These sheep are considered to share a close relationship with the Tibetan breeds (www.fao.org/dad-is). The sheep in south Bhutan (in the districts of Samtse, lower Chukha, Sarpang) could bear similarity with the north east Indian breeds. The ongoing molecular genetic studies based on samples obtained as part of this survey may provide some insights into the origin of Bhutanese sheep.

Indigenous sheep types

Based on coat colour, Tripathi (1963) classified Bhutanese local sheep into four types: Bhutan White Himalayan, Bhutan black Himalayan, Bhutan tan face Himalayan and Bhutan black face Himalayan. Other studies (MoD-AHD, 1975) based on body size, wool quality and quantity, grouped Bhutanese sheep as: Merak-Khaling type (large body, more wool of better quality), Jakar type (small body, less but good quality wool), Rukubji type (small size, small body, coarse wool) and Tsirang-Sipsu type (large body, less and coarse wool). These earlier attempts to describe the Bhutanese sheep breed reflect wide diversity of sheep resources and also indicate the difficulties associated in arriving at a standard breed description.

In this study, it was found that each geographical area presented a distinct sheep population. Sheep type, key identifying characteristics, geographical distribution and approximate population size are summarised in Table 1. Their corresponding physical measurements and horn types are presented in Table 2, while data on coat colour patterns are presented in Table 3. To avoid further confusion on breed description, the approach used by Tripathi (1963) with certain modifications was followed.

For instance, in a previous study, the sheep from Rukubji and Jakar were considered as two different types (Tripathi, 1963). Both these sheep types co-exist in temperate and alpine regions (>2 500 m above sea level) around the black mountain ranges of central Bhutan that comprise the districts of Wangdue, Trongsa and Bumthang. There is very little difference in terms of phenotypic characters such as body size, wool colour and tail features. The sheep have convex heads, with prominent Roman noses. Males have thick and long horns that run backwards, downwards and twist forward. Most females are polled. Local sheep of the area are characteristically of black coat (74 percent) with short tail covered with hairy medium fleece (Figure 2). Since most of its population are centred in the Jakar area, all the central Bhutanese sheep are grouped under the Jakar type.

The sheep population in Merak-Sakten in the east has distinct phenotype. They are larger in body size and produce finer and more quantity of wool (MoD-AHD, 1975). Both sexes have horns. While the horns in males are thick and long, females have thin and short horns. About 52 percent of these sheep have white wool, and another 32 percent have white wool with a black head. Short tails as well as thin tails can be found. These sheep are hardy and capable of walking long distances during migration, they are sensitive and alert which enables them to escape from predators. The sheep from this region are referred to as Sakten type.

Table 1. Sheep types, key characteristic features, distribution and estimated population.

|

Sheep types |

Identifying features |

Distribution |

Population (numbers) |

|

Jakar |

Small body size, predominately black coat colour, brown head and limbs, medium-fine hair, most females are polled, males have horns |

Temperate areas of central Bhutan (Sephu, Phobjikha, Gogona in Wangdue; Tangsibi, Bemji, Jongthang, Semji in Trongsa; Ura, Chumey, Chokortoe, Tang valley of Bumthang). Herded with yak or cattle |

11 000 |

|

Sakten |

Medium body size, white and mixtures of black or brown colour, black or brown head, relatively finer coat; both sexes have horns, roman nose |

Merak, Sakten valley, Khaling, Kanpara, Thrimsing in east Bhutan. Herded with yak, yak hybrids and cattle |

7 000 |

|

Sipsu |

Tall, white and patchy colours, black head, frequent polledness, longer coarse fibre, roman nose, short and tubular ears, known for prolificacy, twins are common |

Subtropical areas in south Bhutan (Darla, Dungna, Phuntsholing in Chukha; Sipsu, Dorokha in Samtse; Beteni, Tsirang and Dagana district) |

6 000 |

|

Sarpang |

Small body size, males have horns, frequent polledness in females, predominately white coat colour, blockier and less leggy |

Subtropical belt in south Bhutan (Bhur, Dekiling and Chekorling in Sarpang district) |

1 000 |

Table 2. Average body parameters of local adult sheep populations of Bhutan.

|

Sheep type |

Sex |

Height at withers (cm) |

Body length (cm) |

Chest girth (cm) |

Paunch girth (cm) |

Ear length (cm) |

Horn length (cm) |

Tail length (cm) |

|

Jakar |

M(n=89) |

63.4±0.5 |

69.8±0.4 |

77.0±0.6 |

77.7±0.7 |

10.8±0.2 |

28.6±1.0 |

15.2±0.2 |

|

F(n=63) |

58.9±0.5 |

65.2±0.5 |

72.1±0.7 |

73.3±0.2 |

10.5±0.0 |

n.a. |

14.4±0.3 |

|

|

Sakten |

M(n=44) |

64.4±0.5 |

66.3±0.6 |

77.3±0.9 |

75.9±1.1 |

10.9±0.2 |

41.2±1.7 |

15.0±0.3 |

|

F(n=28) |

65.4±0.6 |

68.0±0.7 |

80.2±0.8 |

78.9±1.1 |

11.7±0.2 |

16.0±0.7 |

15.2±0.3 |

|

|

Sipsu |

M(n=20) |

70.6±1.0 |

72.9±1.1 |

79.4±1.4 |

78.9±1.9 |

7.9±0.7 |

41.5±2.0 |

17.2±0.7 |

|

F(n=93) |

67.3±0.4 |

71.0±0.5 |

78.6±0.5 |

75.9±0.7 |

8.6±0.3 |

13.8±0.5 |

17.4±0.2 |

|

|

Sarpang |

M(n=5) |

59.8±1.2 |

63.4±3.6 |

69.0±3.0 |

75.6±2.7 |

8.4±1.1 |

14.5±3.5 |

12.2±0.2 |

|

F(n=67) |

57.6±0.5 |

59.5±0.5 |

71.0±0.6 |

74.0±0.9 |

7.2±0.4 |

7.8±0.3 |

11.1±0.2 |

n=Number of animals measured;

M=Male;

F=Female;

Table 3. Proportion of different coat colours and horn characteristics in the local sheep population.

|

Sheep Type |

n |

Pure black |

Pure white |

Pure brown |

White face black body |

Black face white body |

Number polled |

|

Jakar |

155 |

74 |

11 |

3 |

7 |

5 |

45 |

|

Sakten |

72 |

9 |

52 |

4 |

2 |

32 |

15 |

|

Sipsu |

116 |

14 |

38 |

17 |

6 |

25 |

22 |

|

Sarpang |

72 |

0 |

55 |

20 |

0 |

25 |

79 |

n=Number of animals observed.

Figure 2. Jakar type sheep from central Bhutan (Black one).

The sheep from Sarpang are smaller in body size and leggy with coarse wool. They have short ears, a short tail and there is a high proportion of polled animals (79 percent). Males have horns while females are polled, with few exceptions. White is the most common colour (55 percent) followed by brown (20 percent). Although it appears as a distinct group, this sheep population was not reflected in earlier reports. There are several local terms for this sheep such as Bera (which is a general terminology for sheep in the Nepali, Hindi and Bengali language) and Madesi (Indian local sheep). Some farmers simply call them Sarpang Local. Sheep in the locality are mainly reared for mutton with wool as a secondary product. Based on the name of the district, these sheep are referred to as Sarpang type.

The local sheep from Samtse, Tsirang and Chukha have a larger body size and are mostly white (38 percent). Mixtures of black and brown colours however are also frequent. In Tsirang, sheep are further distinguished as Garpala and Bonpala. Traditionally, Garpala sheep are reared in the village settlement whereas Bonpala are taken for migration (gar: home, bon:forest, pala:rearing). However, phenotypically they are not greatly differentiated from sheep in Chukha and Samtse. In Nepal, another name for Bonpala sheep is Baruwal and Gharpala is also called Kagi (Sahana, 2000). They have short and tubular ears, a short tail and are covered with a hairy medium fleece. Herders report that the sheep they have in this area are highly prolific and twins are common. These groups of sheep are well adapted to the subtropical humid climate zone in Bhutan. This group of sheep is referred to as Sipsu type (Figure 3).

Flock size and composition

The average flock size in Table 4 indicates that the number of sheep maintained by a family is smaller in the crop farming community and low altitude areas compared to pastoral areas of temperate Bhutan. This is probably determined by the availability of grazing resources and management differences. Except in Bumthang, the female population is more than male. Bumthang is considered a sacred place with important Buddhist monasteries and religious sites, so communities refrain from slaughter of animals. Sheep owners in Wangdue, Trongsa and east Bhutan also claim that their animals are not used for mutton for religious reasons. However, this seems highly unlikely considering the low proportion of castrates in the flock and ready market for mutton to meet the demand by road construction workers from India. In the east, castrates are often sold to buyers from the Tawang district of Arunachael Pradesh, India.

Figure 3. Sipsu type sheep from south Bhutan

Table 4. Average flock composition and flock size.

|

Region |

Altitude range (m) |

Districts |

Lamb |

Adult |

Average flock size |

||||

|

n |

M |

F |

M |

F |

Ram |

||||

| |

|

Tsirang |

16 |

16 |

35 |

12 |

48 |

11 |

7.6 |

|

Samtse |

20 |

19 |

30 |

10 |

71 |

3 |

6.7 |

||

|

South Bhutan |

150-1 500 |

Sarpang |

13 |

17 |

34 |

4 |

55 |

2 |

8.6 |

| |

Chukha |

19 |

43 |

59 |

16 |

78 |

20 |

11.4 |

|

|

East Bhutan |

2 500-3 500 |

Trashigang |

19 |

32 |

58 |

71 |

191 |

22 |

19.7 |

| |

Trongsa |

23 |

24 |

35 |

64 |

193 |

5 |

14.0 |

|

|

Centre Bhutan |

2 500-4 000 |

Wangdi |

39 |

81 |

66 |

164 |

617 |

16 |

24.2 |

| |

Bumthang |

40 |

40 |

37 |

217 |

216 |

10 |

13.0 |

|

|

Total |

|

|

189 |

272 |

354 |

558 |

1 469 |

89 |

- |

n=Number of households covered;

M=Male;

F=Female.

The proportion of breeding rams to adult females is higher in the flocks of the south compared to those in the migratory herds of central and east Bhutan (Table 4). This probably reflects the difference in the level of breeding management adopted by farmers. South Bhutan farmers manage their animals well in terms of breeding and health care as they derive better incomes from sales of mutton or live sheep. Their sheep are also reported to be superior in terms of reproduction compared to those from other regions. In the migratory flocks of the temperate region, sheep are mostly attended by yak herders and not by the sheep owners themselves. The yak herders earn more profit from yaks than sheep and as such the management, including genetic improvement of sheep receive minimum attention.

Management systems

Seasonal migration is an important characteristic of sheep farming in temperate Bhutan. Farmers reported that the practice of migration enables better feeding resources for sheep and avoids adverse climatic factors. In Wangdue and Trongsa, sheep owners are mainly people who are settled in the villages. Yak herders tend to the sheep under certain arrangements. In Bumthang and also in east Bhutan, the pattern can follow combined rearing of sheep and yak, sheep with cattle or sheep alone. In south Bhutan, sheep farming is mostly in combination with cattle.

The animals graze in the forest, rangeland and other open grazing areas (Figure 4). In alpine areas, flocks are kept in open enclosures during the night. When the sheep are around villages, they are kept in a simple shed constructed nearby. Traditionally, sheep are stalled on the ground floor of the dwelling house. In recent years, due to health consciousness and sanitary considerations, livestock are stalled further away from the house. In east Bhutan, simple bamboo mats are used to make the enclosure. The enclosures are shifted periodically and that particular land used for cultivation of buckwheat/wheat in the following season. Except for salt, sheep do not receive any supplementary feed. Grazing resources are limited. At higher altitudes domestic sheep compete with yak, wild sheep and other herbivores and with cattle at lower altitudes for grazing resources. The majority of the flocks in southern districts are non-migratory and graze in the nearby forest and fallow agricultural land. Households with big flock sizes practice local migration within the villages or districts.

Three times shearing per year is commonly practised but twice shearing is also being followed by a few households in Trongsa and Wangdi. An average wool yield from local sheep is reported to range from 0.3 to 0.8 kg compared to 0.5 to 1.5 kg from crossbred sheep per annual shearing.

Figure 4. Sheep grazing in the forest in central Bhutan.

Socio-economic importance of sheep

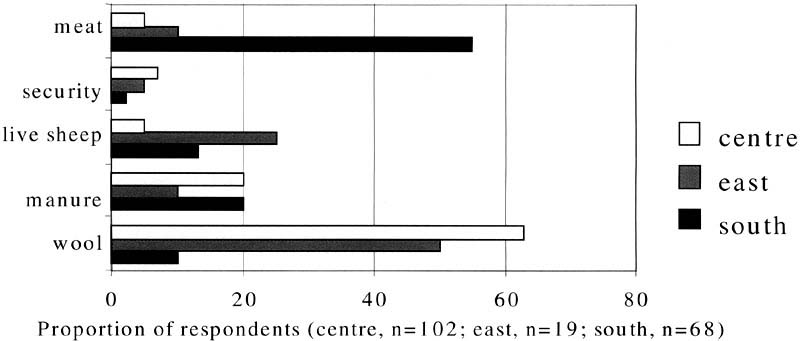

The roles of sheep as reported by the sample households covered in the study are summarised in Figure 5. Wool, manure and security are the most important uses of sheep by farmers in central Bhutan, compared to mutton and manure in southern districts. In east Bhutan, the sale of live sheep to India provides additional income, fetching over Nu 2000 (US$1=Nu 45) per sheep in Tawang. Flock owners reported that in the past their sheep served as an important pack animal, especially to carry salt from Assam, India. This tradition has now stopped with improved road networks and easier access to essential items. Sheep wool is considered an important raw material for making unique traditional garments in the east. In some villages of Trongsa and Wangdue, flock owners also sell raw wool at the rate of Nu 20 to 30 per kg.

Mutton and manure are considered equally important in the southern districts. Mutton is especially important as a source of animal protein because residents there do not consume beef for religious reasons. It is eaten mostly fresh and during festive occasions. Some communities in Samtse use sheep milk to make cheese and butter. Locals consider fermented cheese from sheep milk as a delicacy. The sheep butter when applied to injury from burns is reported to heal the wound much better than conventional therapy. In places like Chukha, farmers derive substantial income from mutton. A kilogram of mutton costs Nu 50-65, a castrated male Nu 2 500 to 3 000 and an adult female sheep around Nu 1 500 to 2 000. In central and east Bhutan, meat from sheep that have died from natural causes are thinly stripped and air dried. Sacrifice of sheep to appease gods or local deity is commonly practised in east and central Bhutan.

Figure 5. Proportion of respondents ranking utility of sheep in different regions of Bhutan

The sheep skin is also of importance, especially in east Bhutan. The shepherds use it as leather garments to protect themselves from cold and rain. In central Bhutan, farmers often use sheep skin as cushions on their backs while carrying loads and also as a sitting mat.

Trends in sheep population

Bhutan had an estimated sheep population of 41 000 in 1986. By 1999, the sheep population had reduced to 25 000 (a decline of 44 percent) (PPD, 1999). The decline in sheep farming and thereby sheep population is more severe in some places than others. For instance, records in the Sephu block of Wangdue a major sheep rearing area in central Bhutan, showed that there were 123 households owning sheep in 1995. In 1998, the number of households rearing sheep had reduced to 31. Nearly 20 households drop sheep enterprises every year. Such drastic changes were not recorded in other regions.

The farmers in central Bhutan expressed that they would like to reduce flock size and a large proportion even mentioned leaving sheep husbandry. Tshering and Acharaya (1996) attributed overgrazing in higher elevations as the reason for the decline in sheep numbers and farmers interest in the sheep husbandry. However, according to the farmers, the main reason is due to cheaply available Indian and foreign garments in the market. In the past, there was no road network and foreign goods were beyond the reach of many people, leading to dependency on their sheep wool for clothing. These days, with changes in fashion, the market for traditional woollen garments is very limited (Ison, 1991). Local weavers also tend to opt for Indian wool, which takes less processing time. Availability of other income-generating sources (potatoes and dairy) and farm labour shortage (children enrolled in schools) are other factors cited for the declining interest in sheep farming.

In Merak-Sakten, herders want to increase flock size because sheep wool is required for the traditional dress (still being preserved and worn by the majority). However, the village elders indicate that the change may come as the young generations are gradually giving up wearing their traditional dress. In southern districts, farmers want to continue sheep farming mainly for mutton as other livestock meat is not preferred for religious reasons.

Conclusion

There is rich diversity among the indigenous sheep populations of Bhutan in terms of body size, wool colour and quality. From a phenotypic description and geographical locations, four native types can be recognised (Jakar, Sakten, Sipsu and Sarpang types). Molecular genetic characterisation, which is currently underway, will, hopefully, help clarify the relationships among these ‘types’, existing diversity and evolutionary history.

Traditional sheep farming has become less profitable, especially in central Bhutan and the sheep population is showing a declining trend. The future of sheep in Bhutan may lie in the development of mutton type sheep in the southern districts and a dual-purpose sheep in the East. Existence of diverse local types both in terms of body size and wool quality gives good opportunity to develop the indigenous sheep industry through selective breeding. Selective breeding of local sheep may also ensure long-term conservation and sustainable use of native sheep genetic resources in Bhutan.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Mr Dawa Sherpa, District Animal Husbandry Officers and Livestock Extension Agents in the survey areas for their assistance in the field data collection. Thanks to Dr Sonal Nagda for his help with data analysis. We remain indebted to Mr Kinzang Wangdi, Dr Walter Roder and Mr Sonam Tamang for their support and advice.

References

MOD-AHD. 1975. Report on survey of sheep and yak in Bhutan. Royal Government of Bhutan, 2-20.

Bennett, P.R. 1980. Report to the Government of Bhutan on the national sheep breeding programme. UNDP, BHU/72/010, pp. 54.

DAD-IS, FAO. http:www.fao.dad-is

Ison, B. 1991. Final report for ACIL Australia Pty Limited. Consultancy from 11 to 21 August 1991. Bhutan-Australia Sheep Development Project, pp. 48.

PPD, 1999. Livestock Census, Ministry of Agriculture, Bhutan.

Ryder, M.L. 1984. Sheep. In: Evolution of domesticated animals. Ian L. Mason (Ed.), Longman, London, 63-99.

Sahana, G. 2000. Sheep and goat genetic resources of the Indian subcontinent. In: Domestic Animal Diversity Conservation and Sustainable Development. R. Sahai and R.K. Vijh (Eds), SI Publications, Karnal, 188-219.

Tripathi, P.C. 1963. Report on sheep rearing and wool production in Bhutan. Report to the Government of Bhutan (Development Wing), pp. 26.

Tshering, L & Acharya, T.N. 1996. Bhutan. In: Proceeding of the first regional training workshop on conservation of domestic animal diversity. GCP/RAS/144/JPN. FAO, Bangkok, 3-25.

Vij, P.K., Tantia, M.S. & Nivsarker, A. E. 1997. Characteristics of Bonpala sheep. Animal Genetic Resources Information 22, 15-18.

Wangmo, S. undated. The Brokpas: A semi-nomadic people in Eastern Bhutan. In: Himalayan Environment and Culture. N.K Rustomji & C. Ramble (Eds), Indus Publishing Company, New Delhi, India, 140-158.

|

[16] Renewable Natural

Resources Research Centre, Jakar, Bhutan [17] National Sheep Breeding Centre, Bumthang, Bhutan [18] International Livestock Research Institute, Nairobi, Kenya [19] International Livestock Research Institute, Nairobi, Kenya |