by

P. Umarov

11 Kazaksu-4, Tashkent,

700187, Uzbekistan

Irrigation in Uzbekistan has been practised for thousands of years, but the large-scale infrastructure was constructed only during the Soviet period in response to the growing demand for cotton. Eventually cotton production used more than 90 percent of total water resources available in the country.

Since independence in 1990, Uzbekistan, as the major water user in Central Asia, has found itself in a difficult situation as a result of declining water management and growing water deficit, as well as lack of funds for further irrigation development. Water management activities have lately focused on operation of old irrigation systems and negotiating transboundary water problems. Fisheries, introduced in the region several decades ago in order to compensate for the loss of the Aral Sea fish catch, use irrigation and drainage systems. Under the favourable climatic conditions of Uzbekistan these waterbodies have a high potential for fish production.

However, constraints arising from the existing problems with water management of irrigation systems as well as those caused by other uses of water in Uzbekistan negatively affect fish production. Over the last ten years the fish production from waterbodies of irrigation systems decreased threefold. All fisheries are now privatized, but the privatization has resulted in decline of the formerly well developed fisheries research and management structures. Coordination among fisheries institutions responsible for maintaining sustainable fish yields in a great diversity of waterbodies serving and arising from irrigated agriculture has been disrupted. Linkages between the irrigation and fishery institutions have been lost, and there is lack of new initiatives and research projects facilitating and promoting the use of irrigation systems for fish production.

There is an urgent need for improving intersectoral cooperation in integrated water management, as well as a need for pilot research projects which would test the best fish enhancement practices for Central Asia. While the use of water for irrigated agriculture is still government priority, and the proposed new reforms in agriculture and water management, when implemented, will create a favourable environment for fish production, Uzbekistan needs international support, including funding. Further assistance is needed to establish a regional information network for exchanging information on the best possible use of irrigation systems for fish production. This also requires the international assistance of specialized fisheries organizations and institutions, such as FAO, NACA, etc. Introducing the best existing practices of fish production in irrigation and drainage waterbodies, selected from global experience, is of high importance for improving food security in the Region. While at present no regional network exists to deal specifically with the use of irrigation systems for fish production in arid countries, there is a potential for cooperation in the use of irrigation systems for fish production at the regional level. It is believed that the Interstate Commission for Water Coordination (ICWC), based in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, is a body capable of taking up this function.

1.1 Status of irrigation development

Water is one of the major factors on which life and development in Central Asia depend. Irrigation was one of the main uses of water in the region from time immemorial, its origins dating back to the seventh millennium B.C. By the beginning of the twentieth century there were 2.5-3.5 million ha of irrigated lands in the Region, supported by an extensive irrigation network. When Uzbekistan was part of the Soviet Union water resources in Uzbekistan were subject to large-scale engineering modification, as demanded by the growing irrigated agriculture, basically for cotton production.

Water resources in Uzbekistan are part of the water resources of the Aral Sea basin (Map 1). This basin includes two major rivers of Central Asia: the Amu-Darya and the Syr-Darya, which are the main sources of surface flow. The portion of water originating directly from the territory of Uzbekistan is 6.3 percent in the Amu-Darya basin and 16.5 percent in the Syr-Darya basin, which represents 9.6 percent of their total flow (Anon., 1997) (Table 1). The water is stored in numerous reservoirs (Table 2) from where it is distributed on demand.

Table 1

River discharges in the Aral Sea basin

(km3/year)

|

State |

River basin |

Aral Sea basin |

||

| |

Syr-Darya |

Amu-Darya |

km3 |

percent |

|

Kazakhstan |

2 624 |

- |

2 626 |

2,1 |

|

Kyrgyzstan |

27 605 |

1 604 |

29 209 |

25.1 |

|

Tajikistan |

1 005 |

59 578 |

60 583 |

52.0 |

|

Turkmenistan |

- |

1 549 |

1 549 |

1.2 |

|

Uzbekistan |

6 167 |

5 056 |

11 223 |

9.6 |

|

Afghanistan and Iran |

- |

11 593 |

11 593 |

10.0 |

|

Total Aral Sea basin |

37 203 |

79 280 |

116 483 |

100 |

The use of water resources by different sectors of Uzbekistan is shown in Table 3. The main water use beneficiaries in Uzbekistan are irrigated agriculture, which uses 90 percent of the available water, drinking and rural water supply, industries and fisheries. These sectors also generate 28.2 km3 of return waters (Anon., 2000). Intensive development of irrigation and drainage in the Aral Sea basin has had two major impacts on water quantity and quality in the rivers: a major freshwater uptake for irrigation, and generation of polluted return water of elevated salinity.

More then 50 percent of the total irrigated area in Central Asia (4.3 million ha) is located in Uzbekistan. While the area under irrigation during the 10 years of independence remained the same there were some changes in the crop pattern. Cotton still remains the priority crop; however, its share in irrigated agriculture has decreased from 50 to 40 percent. The share of cereals (wheat, rice, maize etc.) has increased from 13 to 30 percent. The share of fodder crops has remained the same at 20 percent of the total (Anon., 2001).

Map 1

Location of the Aral Sea basin

The irrigation infrastructure of Uzbekistan comprises an interconnected irrigation system of canals and drainage collectors, with freshwater and drainage (return) water flows. In Uzbekistan there are 28 000 km of main and inter-farm irrigation canals and 168 000 km of in-farm irrigation canals. The total length of main and inter-farm collectors is more than 30 000 km and there are 107 000 km of in-farm collectors (Anon., 2000) (Table 4).

Table 2

Reservoirs in the Aral Sea basin (SIC ICWC

data base) (million m3 = Mm3)

|

Name |

In |

Total |

Dead |

Source |

|

Mm3 |

Mm3 |

|||

|

Amu-Darya River basin |

||||

|

Uzbekistan |

||||

|

Tuyamuyun |

1980 |

7 800 |

2 550 |

Amu-Darya |

|

Tudakul |

1986 |

1 200 |

50 |

Andijan Great canal |

|

Òalimazhan |

1978 |

1 525 |

125 |

Karshi main canal |

|

South Surhan |

1962 |

800 |

210 |

Surhandarya |

|

Tupolang |

1985 |

500 |

30 |

Tupolang |

|

Shurkul |

1978 |

170 |

17 |

Zerafshan |

|

Kuya- Mazar |

1957 |

320 |

80 |

Andizhan Great canal |

|

Akdarya |

1989 |

130 |

20 |

Akdarya |

|

Kattakurgan |

1941 |

840 |

24 |

Zerafshan |

|

Karaultube |

1984 |

53 |

3 |

Zerafshan |

|

Kamashi |

1957 |

29.5 |

5.7 |

Yakkabagdarya |

|

Kattasai |

1961 |

55 |

15 |

Kattasai |

|

Pachkamar |

1967 |

260 |

17 |

Guzadarya |

|

Dehkanabad |

1983 |

27.2 |

3 |

Kychyk-Uradarya |

|

Chimkurgan |

1959 |

425 |

0 |

Kashkadarya |

|

Gissarak |

1982 |

170 |

15 |

Àksu |

|

Uchkyzyl |

1959 |

160 |

80 |

Zang canal |

| |

Total |

14 464.7 |

3 244.7 |

|

|

Turkmenistan |

||||

|

Zeid |

1963 |

2 200 |

200 |

Garagum canal |

|

Hauzhan |

1962 |

875 |

25 |

Garagum canal |

|

Western |

1962 |

48 |

10 |

Garagum canal |

|

Kopetdag |

1985 |

220 |

25 |

Garagum canal |

|

Ioloten |

1910 |

73.2 |

1.5 |

Murgap |

|

Kolhoz-Bent |

1941 |

54.6 |

4.6 |

Murgap |

|

Kaushutbentå |

1895 |

38.2 |

4.5 |

Murgap (lower and middle) |

|

Sary-Yazin |

1950 |

263 |

15 |

Murgap |

|

Tedzhen II |

1960 |

183.5 |

3.5 |

Tedzhen |

|

Tedzhen I |

1950 |

150 |

7.4 |

Tedzhen |

|

Hor-Hor |

1959 |

21.5 |

0.9 |

Tedzhen |

|

Mamed-kul |

1964 |

20.5 |

2.5 |

Àtrek |

|

Òàshkeprin |

1939 |

166 |

18.3 |

Murgap, Êushka |

| |

Total |

4 313.5 |

3 182 |

|

|

Tajikistan |

||||

|

Muminobod |

1959 |

30.1 |

0.9 |

Obisurh |

|

Selbur |

1961 |

26 |

0.6 |

Kyzylsu |

|

Sangtuda |

1980 |

270 |

0 |

Vakhsh |

|

Golovnaya GES |

1963 |

21.6 |

11 |

Vakhsh |

|

Baipaza |

1978 |

97 |

13.5 |

Vakhsh |

|

Nurek |

1970 |

10 500 |

5 964 |

Vakhsh |

| |

Total |

10 944.7 |

5 990 |

|

|

Syr-Darya River basin |

||||

|

Tajikistan |

||||

|

Kairakkum |

1956 |

3 413.5 |

894 |

Syr-Darya |

|

Kattasai |

1961 |

55 |

21.4 |

Kattasai |

| |

Total |

3 468.5 |

915.4 |

|

|

Kyrgyzstan |

||||

|

Toktogul |

1974 |

19 500 |

5 500 |

Naryn |

|

Uchkurgan |

1901 |

52.5 |

31.6 |

Naryn |

|

Kurpsai |

1983 |

370 |

20 |

Naryn |

|

Kurgantepa |

1978 |

33.3 |

5.5 |

Shahimardan |

|

Naiman |

1971 |

39.5 |

1.5 |

Abshirsai, Kyrgyzatan |

|

Papan |

1981 |

260 |

10 |

Akbura |

| |

Total |

20 255.3 |

5 568.6 |

|

|

Uzbekistan |

||||

|

Dzhizak |

1968 |

100 |

4 |

Sanzar |

|

Zaamin |

1979 |

51 |

21 |

Zaaminsu |

|

Charvak |

1966 |

2 000 |

420 |

Chirchik |

|

Tuyabuguz |

1959 |

250 |

26 |

Ahangaran |

|

Ahangaran |

1971 |

260 |

30 |

Ahangaran |

|

Farhad |

1947 |

350 |

330 |

Syr-Darya |

|

Kassansai |

1942 |

165 |

10 |

Kassansai |

|

Karkidon |

1963 |

218.4 |

4.4 |

Kuvasai and South Fergana canal |

|

Andijan |

1978 |

1 900 |

150 |

Karadarya |

| |

Total |

5 294.4 |

995.4 |

|

|

Kazakhstan |

||||

|

Bugun’ |

1965 |

350 |

10 |

Bugun’ |

|

Chardara |

1966 |

5 700 |

1 000 |

Syr-Darya |

| |

Total |

6 050 |

1 010 |

|

|

Total for Aral Sea basin |

64 791.1 |

18 042.3 |

|

|

|

Incl. Amu-Darya |

29 722.9 |

9 552.9 |

|

|

|

Syr-Darya |

35 068.2 |

8 489.4 |

|

|

Table 3

Water use in Uzbekistan (million

m3) (SIC ICWC data base, Statistics Yearbooks 10-20)

(*at rayon =

district boundaries)

|

Year |

Source |

Drinking |

Rural |

Industry |

Fishery |

Irrigation* |

Other |

Total |

Basin |

|

1960 |

|

200 |

250 |

500 |

500 |

13 930 |

0 |

15 380 |

Amu |

|

280 |

250 |

700 |

200 |

13 970 |

0 |

15 400 |

Syr |

||

|

480 |

500 |

1 200 |

700 |

27 900 |

0 |

30 780 |

Total |

||

|

1965 |

|

220 |

350 |

600 |

500 |

19 800 |

0 |

21 470 |

Amu |

|

300 |

350 |

900 |

300 |

17 980 |

0 |

19 830 |

Syr |

||

|

520 |

700 |

1 700 |

800 |

37 780 |

0 |

41 500 |

Total |

||

|

1970 |

|

250 |

480 |

1 100 |

130 |

23 550 |

0 |

25 510 |

Amu |

|

450 |

500 |

1 400 |

300 |

19 900 |

0 |

22 550 |

Syr |

||

|

700 |

980 |

2 500 |

430 |

43 450 |

0 |

48 060 |

Total |

||

|

1975 |

|

300 |

900 |

2 260 |

300 |

25 600 |

100 |

29 460 |

Amu |

|

500 |

1 050 |

2 600 |

700 |

19 850 |

250 |

24 950 |

Syr |

||

|

800 |

1 950 |

4 860 |

1000 |

45 450 |

350 |

54 410 |

Total |

||

|

1980 |

|

400 |

1 090 |

2 150 |

200 |

29 060 |

300 |

33 200 |

Amu |

|

660 |

1 300 |

2 500 |

510 |

26 450 |

290 |

31 710 |

Syr |

||

|

1 060 |

2 390 |

4 650 |

710 |

55 510 |

590 |

64 910 |

Total |

||

|

1985 |

|

440 |

440 |

240 |

130 |

32 708 |

0 |

33 958 |

Amu |

|

1 100 |

450 |

1 000 |

290 |

21 596 |

0 |

24 436 |

Syr |

||

|

1540 |

890 |

1240 |

420 |

54 304 |

0 |

58 394 |

Total |

||

|

1990 |

|

704 |

349 |

196 |

353 |

35 048 |

0 |

36 650 |

Amu |

|

1 650 |

374 |

1102 |

727 |

23 108 |

0 |

26 961 |

Syr |

||

|

2 354 |

723 |

1298 |

1080 |

58 156 |

0 |

63 611 |

Total |

||

|

1995 |

Total: |

630 |

520 |

250 |

280 |

30 030 |

0 |

31 710 |

Amu |

|

Surface water |

0 |

0 |

150 |

280 |

27 230 |

0 |

27 660 |

|

|

|

Ground water |

630 |

520 |

100 |

0 |

1 000 |

0 |

2 250 |

|

|

|

Drainage re-use |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 800 |

0 |

1 800 |

|

|

|

1995 |

Total: |

1 400 |

570 |

950 |

600 |

18 990 |

0 |

22 510 |

Syr |

|

Surface water |

0 |

0 |

300 |

600 |

15 490 |

0 |

16 390 |

|

|

|

Ground water |

1 400 |

570 |

650 |

0 |

1 500 |

0 |

4 120 |

|

|

|

Drainage re-use |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 000 |

0 |

2 000 |

|

|

|

1995 |

Total: |

2 030 |

1 090 |

1 200 |

880 |

49 020 |

0 |

54 220 |

Total |

|

Surface water |

0 |

0 |

450 |

880 |

42 720 |

0 |

44 050 |

|

|

|

Ground water |

2 030 |

1 090 |

750 |

0 |

2 500 |

0 |

6 370 |

|

|

|

Drainage re-use |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

3 800 |

0 |

3 800 |

|

|

|

1999 |

Total: |

1 428 |

993 |

527 |

435 |

34 830 |

0 |

38 213 |

Amu |

|

Surface water |

0 |

0 |

277 |

435 |

32 255 |

0 |

32 967 |

|

|

|

Ground water |

1 428 |

993 |

250 |

0 |

557 |

0 |

3228 |

|

|

|

Drainage re-use |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 018 |

0 |

2 018 |

|

|

|

1999 |

Total: |

1 205 |

396 |

817 |

372 |

21 830 |

0 |

24 620 |

Syr |

|

Surface water |

0 |

0 |

287 |

372 |

18 096 |

0 |

18755 |

|

|

|

Ground water |

1 205 |

396 |

530 |

0 |

1 600 |

0 |

3 731 |

|

|

|

Drainage re-use |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2134 |

0 |

2134 |

|

|

|

1999 |

Total: |

2 633 |

1 389 |

1 344 |

807 |

56 660 |

0 |

62 833 |

Total |

|

Surface water |

0 |

0 |

564 |

807 |

50351 |

0 |

51 722 |

|

|

|

Ground water |

2 633 |

1389 |

780 |

0 |

2 157 |

0 |

6 959 |

|

|

|

Drainage re-use |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4 152 |

0 |

4 152 |

|

Table 4

Main collectors in the Amu-Darya and

Syr-Darya river basins, discharge in 1999

(SIC ICWC database)

|

Main collectors |

Average flow rate |

Salinity |

Annual |

Discharged into |

|

KS-1 |

12.6 |

4 |

400 |

Aral Sea area |

|

KS-3 |

5.3 |

4.1 |

168 |

Aral Sea area |

|

KS-4 |

4.3 |

2.65 |

138 |

Aral Sea area |

|

KKS |

18.4 |

5.4 |

581 |

Sudoche lake |

|

Beruny |

10.1 |

3.9 |

321 |

Amu-Darya river |

|

Ayazkala |

12.4 |

4 |

392 |

Ayazkala lake |

|

Ustyurt |

6.6 |

4 |

209 |

Sudoche lake |

|

Ozerny |

73.1 |

4.1 |

2 308 |

Sichankul lake |

|

Divankul |

31.1 |

2.7 |

981 |

Sichankul lake |

|

Parsankul |

28.1 |

3 |

884 |

Amu-Darya river |

|

Dengizkul |

14.3 |

4.9 |

451 |

Dengizkul lake |

|

Central Bukhara Canal |

15.5 |

3.05 |

490 |

Solyonoe lake |

|

Zalodno-Romiton |

2.5 |

2.4 |

79 |

Solyonoe lake |

|

Agitma |

5.5 |

2.1 |

174 |

Agitmin lake |

|

Severny |

22.6 |

2.9 |

713 |

Korakir lake |

|

Yuzhny |

74.2 |

7.1 |

2 339 |

Sultandag lake |

|

Central Golodnaya Steppe Canal |

43.1 |

4.2 |

1 360 |

Arnasay depression |

|

Shuruzak |

12.7 |

2.8 |

400 |

Syr-Darya river |

|

DGK |

11.2 |

3.5 |

354 |

Kly collector |

|

Ok-Bulok |

3.9 |

3.9 |

122 |

Tuz kony lake |

|

Pogranichny |

1.8 |

4.5 |

58 |

Tuz kony lake |

|

Kly |

3.23 |

4.7 |

102 |

Arnasay depression |

|

Achikkul |

49.5 |

2.65 |

1 560 |

Syr-Darya river |

|

Korakalpak |

9.6 |

1.57 |

302 |

Syr-Darya river |

|

Sari-Suv |

65.8 |

1.5 |

2 074 |

Syr-Darya river |

|

Urtukly |

20.6 |

1.3 |

650 |

Syr-Darya river |

|

Chilisay |

11.2 |

1.27 |

350 |

Syr-Darya river |

There has been practically no further irrigation development in Uzbekistan since independence. Management of water resources has focused on operation and maintenance of the existing systems. For instance, in 1994 the capital investment in irrigation development was 37 percent of that of 1990, and only 5 percent in 1999 (Scientific Information Centre of the Interstate Coordination Water Commission - SIC of ICWC). At the same time funds for the operation and maintenance of irrigation systems in 1999 decreased by 32 percent compared to their level in 1990. In 1999, the operating costs of water resources organizations of Uzbekistan were US$436.1 million, or US$103.8 per ha.

In the region, i.e. Central Asia, Uzbekistan is the largest water user with the least potential to generate water resources. There is therefore a great need to overcome water deficit and to solve the problems of transboundary water resources management. Old principles of water management which were applied to the whole region prior to independence, giving priority to irrigated agriculture, are not in accordance with the priority of water use as a basic source of power generation in the independent states located in the upper watershed area (Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan). This leads to a conflict of interests between upstream and downstream states. To develop cooperation in the field of joint management, protection and use of water resources, the regional ICWC with its executive bodies, the Basin Water Organisations (BWO) Amu-Darya and Syr-Darya, and the Scientific Information Centre of ICWC were established in 1992 by the initiative of the ministers of five Central Asian states. The present structure of water resources management in the region consists of two levels, i.e. interstate and national.

The present national institutional setting responsible for irrigation development and management in Uzbekistan consists of a number of departments financed by the government.

The main constraints to irrigation development in Uzbekistan are:

inadequate system of centralized command management of land and water resources;

insufficient financing;

rising water deficit;

conflict of water development interests between upstream and downstream countries in the Amu-Darya and Syr-Darya river basins;

physical and functional deterioration of water assets;

migration of qualified personnel due to the decreasing living standard;

environmental problems caused by deterioration of water quality, Aral Sea desiccation and desertification of Priaralye (areas around the Aral Sea).

1.2 Status of the use of irrigation systems for fish production

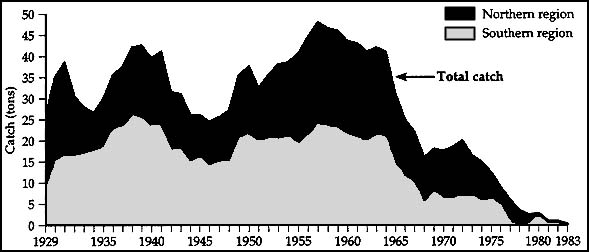

Until 1960 fisheries of Uzbekistan were concentrated predominantly in the Aral Sea area. In 1958 fish catches reached a maximum of 50 000 tonnes (Fig. 1). As a result of the Aral Sea desiccation and increased salinity to 14 g/litre (the salinity in 1983), there has been no fishing in the Aral Sea since 1983. Fisheries have moved to delta lakes and Lake Sarykamysh formed from drainage waters. But Sarykamysh also eventually lost its fishery value due to an increase in salinity which by now reached in some areas 20 g/litre. Today’s fish yields in lakes and reservoirs in the Aral Sea area range from 1.2 to 209 kg/ha (Anon., 1990, 1998, 2001a) (Table 5).

Fig. 1

Fisheries in the Aral Sea zone (Zholdasova

et al., 1996)

Table 5

Fish production in lakes and reservoirs

owned by the State Joint Stock Company Karakalpak Fisheries (Anon.,

2001a)

|

Lake or reservoir |

Area |

Depth |

Width |

Production |

Reservoir location |

Name of fishing |

|

Domalak, Janly - close to Domalak lakes |

2 000 |

1.2 -1.5 |

3.5 - 4.0 |

80 |

Muinak region right bank of Amu-Darya |

Muinak fish processing factory |

|

Karateren lake - located at Damalike |

1 000 |

1.2 - 1.5 |

3.5 - 4.0 |

40 |

Muinak region right bank of Amu-Darya |

Kazakh-Darya fish processing factory |

|

Shege |

3 000 |

1.3 - 1.8 |

3.5 |

66 |

Muinak region, northwestern part of Mezhdurechye |

Amu-Darya state-owned fisheries company (sovkhoz) |

|

Kok-suu |

1 500 - 2 500 |

1.3 - 1.8 |

25 |

40 |

|

|

|

Sudachye including Ak-ushpa, Taily and Urge lakes |

3 300 |

0.7 - 0.8 |

1.7 |

59 |

Northeastern part of the left bank of Amu-Darya near GLK collector in the west of Sudachye lake |

Uchsay fish processing factory |

|

Large Sudachye lake |

|

|

|

|

Near GLK collector in the east part of lake Sudachye |

Konyrat fish processing factory |

|

All close to Makpalkol lakes: Makpal, Sarhocha, Birkazan Kisilkeme |

600 |

1.0 - 1.5 |

3 |

24 |

Muinak region, left part of lower Amu-Darya |

Tentekarna state-owned fisheries company |

|

Keyser lake located at Karajar |

16 000 - 20 000 |

2.0 - 2.2 1.0 - 1.2 |

3 3 |

39 88 |

Muinak region, left part of Amu-Darya |

Taly-uzyak state-owned fisheries company |

|

Ilmekol lake located at Karajar |

1 000 - 1 500 |

|

|

|

Muinak region, central part of Amu-Darya left bank near Karakhar |

Tentekarna state-owned fisheries company |

|

Khojahol Lake located at Khojakol |

1 000 |

2 |

3.5 |

55 |

Kungrad region, southern part of Khojakol lake |

Konrat fish processing factory |

|

Koptin-kol Lake located at Khojakol |

9 500 |

1.2 - 2.0 |

6 |

209 |

Kungrad region, central part of Amu-Darya left bank and near Khojakol lake |

Konrat fish processing factory |

|

Jaunger-kol Lake located at Khojakol |

532 |

1.7 - 1.8 |

2.5 - 3.0 |

8 |

Kungrad region, central part of Amu-Darya left bank and near Khojakol lake |

Konrat fish processing factory |

|

Muinak gulf |

9 750 |

1.65 |

3 |

78 |

Muinak region, southeastern part of the Aral Sea |

Nurly-hol fisheries cooperative |

|

Rybachy gulf (Sarybas) |

4000 |

1.0 - 1.5 |

3.4 |

34 |

Munaik region in 1 km to the North of Muinak in the southern part of dried bed of the Aral Sea |

Tentek Arna fish processing factory |

|

Sarykamysh |

300 000 |

5.7 |

47 |

33 |

South-west of the Aral Sea, 200 km from Turkmenistan border with Karakalpakstan |

|

|

Shygys Carateren |

4 000 |

3 - 5 |

30 |

52 |

Tahtakul region, foot of Beltau Height |

Tahtakul fishery |

|

Botakol and nearby lakes |

2 000 |

1.5 - 2.0 |

4 |

18 |

Tahtakulsky region between Karateren lake and Kok-Darya River (KS - 4) |

|

|

Atakol and nearby lakes |

2 000 |

1.5 - 2.0 |

3.5 - 4.5 |

10 |

Tahtakulsky region |

|

|

Tashpenkol |

1 000 |

1.5 - 3 |

10 |

1.2 |

Wimbaisk region, Amudarya right bank, Kuskanatau Height |

Wimbaisk fishery |

|

Dauytkol reservoir |

5 000 |

1.5 - 2.0 |

7 |

80 |

Amu-Darya right bank, 47 km to the north of Nukus |

Nukus fish processing factory |

|

Karakol |

7 000 |

0.9 - 2.6 |

2.6 |

115 |

Northwestern part of Shumanai region |

Shumanai fishery |

|

Akshakol |

4 000 |

1.5-20.0 |

7 |

20 |

Ellicalin region, Amu-Darya right side, 20-30 km from southeastern part of Sultanuzdag |

Ellikalin fishery |

|

Ayazkala |

9 000 |

2 - 3 |

8 |

40 |

Berunian region, Amu-Darya right bank and southern part of Sultanuzdag |

Berunina fishery |

|

Zhyltyrbas |

30 000 |

|

|

|

Muinak region |

Kasakhdarya fish processing factory |

|

Kobeyshungil, Sarykol, Magnit zhargan |

50 |

1.0- 1.5 |

2 |

0.3 |

Karauzyak region |

Karauzyak fishery |

When Uzbekistan was part of the Soviet Union, the Ministry of Fisheries of the former USSR, in cooperation with the Ministry of Water Management and Uzbekistan Government, in the 1960s-1970s developed a large-scale comprehensive programme of fish production for all types of inland waterbodies. Special attention was paid to education, research, planning, water and fish quality monitoring and other issues. Due to the presence of irrigation systems throughout the plains of Uzbekistan, fisheries planners, developers and managers had to make the best use of different types of irrigation waterbodies (reservoirs, irrigation and drainage canals, lakes storing drainage water).

State-owned fishing companies were established at all large reservoirs and lakes for return water storage. Hatcheries for producing stocking material were constructed in all parts of Uzbekistan. By the 1980s up to 7 000 tonnes of fish per year were harvested from reservoirs and lakes. All fish farms were state owned, financed by the government, and functioned within the structure of the Ministry of Fisheries. They regularly reported on their fish production.

After the dissolution of the USSR the situation changed significantly. The government of Uzbekistan privatized all state-owned fish farms and capture fisheries enterprises and stopped their government financial support. As a result fish production dropped to one third and large-scale fishing in reservoirs such as Charvak, Chimkurgan and several others virtually stopped or was significantly reduced, as for example in Tudakul reservoir, where the reported fish catches dropped from 700 tonnes in the early 1990s to 250 tonnes in the late 1990s. Fish production in ponds has decreased on the average from 3 000 kg to 850 kg per ha. Education and training of specialists also stopped, and the research network came to an almost complete standstill (Kamilov, this volume).

Today, Uzbekistan has no national programme or specific fishery development projects supported by the government or international assistance. Private initiative focuses only on exploitation of rich fish stocks in the Aidaro-Arnasay system using small fishing teams. The fishery potential of waterbodies of the irrigation system of Uzbekistan is largely unexploited.

Between 1996 and 2001 two project proposals were formulated for the development of fisheries on fish farms of the enterprise "Uzbalik". One, a project for a model aquaculture farm using semi-intensive technology, was prepared in cooperation with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Israel; the other, for a fish farm for sturgeon production, was prepared in cooperation with a German company. Both projects have not yet been implemented, mainly for the lack of funds on the Uzbek side and because of insufficient experience of Uzbek fishery specialists in implementing such projects.

Prior to independence some experience was obtained in using irrigation systems for fish production in the Golodnaya and Karshy steppes. In the Southern Golodnaya Steppe Canal an experimental fish hatchery for grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) and silver carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix) was constructed and operated during 1975-1985. This hatchery produced fingerlings for stocking irrigation canals overgrown with aquatic macrophytes. Fish stocked into the canals cleared them almost completely of aquatic plants and the fish themselves were afterwards harvested for food. While this approach is considered by fishery specialists and engineers as an efficient aquatic weed controlling mechanism, the hatchery ceased functioning and canals are now again overgrowing with aquatic plants. In Karshy steppe there was fisheries in Talimarjan reservoir, and fish ponds were constructed to use drainage waters of Sichankul and Sultan Uezdak. These ponds became successful in fish production. Even this undertaking is now largely neglected.

Irrigation systems are present throughout Uzbekistan. Uzbekistan has a good transportation and industrial infrastructure, large rural population and diversified agriculture. All this creates favourable social and economic conditions for development of fish production in all waterbodies connected with irrigation.

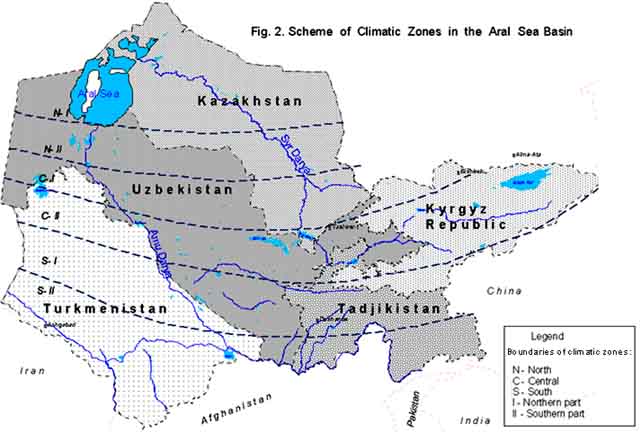

Uzbekistan is located in a climatic zone favourable for development of aquaculture in natural waterbodies and in reservoirs (Fig. 2). There is a long season of warm and sunny weather which keeps water warm. The existing water resources provide for a large increase in both capture fisheries and aquaculture. The presence of cold waters at a higher altitude enables production of cold water fish, including trout.

The lowland reservoirs of the Zaravshan, Kashka-Darya, Surkhan-Darya basins of the Amu-Darya middle reaches are suitable for the development of capture fisheries based on warmwater Chinese carps, i.e. silver, bighead, and grass carp, and common carp. In the mountain and foothill storage reservoirs such as Charvak, Akhangaran, Andizhan and several others one could produce cold water fish such as rainbow trout, Issyk-Kul (Sevan) salmon and whitefish (Coregonus spp.). It would be profitable to use the existing ponds, now in private ownership, for creation of fish farms. With a model of a profitable small fish farm, farmers of Uzbekistan could then combine pond fish culture with the traditional farm crop production. This would appear to be an efficient way of boosting the fish production in the country.

Fish hatcheries in Uzbekistan are still functioning, including the breeding and production of fish fry and fingerlings of cyprinids. They have sufficient capacity to provide potential farmers with the required quantities of fry, fingerlings and yearlings for increasing fish production to up to 100 000 tonnes per year. Prior to independence the Uzbekistan fish farms supplied all Central Asia, southern Siberia and some other regions with fry and fingerlings (Kamilov, this volume).

Today there is an obvious shortage of fish in Uzbekistan, with a fish supply of less than 1 kg/person/year. Before 1990 the country processed and consumed annually 70-100 000 tonnes of fish, of which 30 000 tonnes were from the local production, and 40-70 000 tonnes imported. Today’s consumption is only 9-10 000 tonnes (Kamilov, this volume).

The following conditions favour further development of fisheries in Uzbekistan:

social - optimum density of population and need to create new workplaces;

economic - proximity to markets, especially to those with traditionally high fish demand; proximity to large industrial centres, which would facilitate introduction of new technologies for production and marketing of high value fish species;

climatic - high level of solar radiation, diversity of climatic zones favouring the production of both warm water and cold water fish species;

technological - availability of both irrigation and drainage canals-collectors for fish production (Table 6).

Fig. 2

Climatic zones in the Aral Sea basin

Table 6

Return waters in the Aral Sea basin (SIC ICWC data base)

Return waters in the Amu-Darya River basin (Uzbekistan) (million m3 = Mm3)

| Catchment areas, | Years of | Catch- | Main | Average | Return | Diverted | ||

| to a | to | for | ||||||

| Upper reaches | | | | | | | | |

| Surkhandarya | 1990 | 311 | Karasu river | 2.35 | 1 138 | 510 | - | 628 |

| | 1995 | 324 | Antorsky collect. | 1.55 | 1 398 | 803 | - | 595 |

| | 1999 | 320 | VST, K-1, K-2, ...K-5 | 2.2 | 1 100 | 600 | - | 500 |

| Middle reaches | | | | | | | | |

| a) Kashkadarya | 1990 | 485 | Yuzhny collector | 6.76 | 1 722 | 654 | 1 068 | - |

| | 1995 | 495 | Kashkadarya river | 5.74 | 2 043 | 650 | 1 393 | - |

| | 1999 | 490 | | 7.1 | 2 340 | 800 | 1 540 | - |

| b) Bukhara | 1990 | 343 | Parsankul, Central | 3.69 | 2 273 | 650 | 1 623 | - |

| | 1995 | 390 | Bukhara Canal | 3.11 | 1 938 | 510 | 1 428 | - |

| | 1999 | 385 | Severny collector Dengizkul | 4.2 | 2 790 | 810 | 1 980 | - |

| Lower reaches | | | Ozerny collector | | | | | |

| a) Khorezm | 1990 | 258 | Divankul collector | 2.98 | 2 740 | - | 2 561 | 179 |

| | 1995 | 267 | | 2.02 | 4 009 | - | 3 819 | 190 |

| | 1999 | 256 | | 3.7 | 3 290 | - | 3 110 | 180 |

| b) Karakalpakstan | 1900 | 495 | KS-1, KS-3 | 4.2 | 2 332 | 388 | 1 944 | - |

| | 1905 | 500 | KS-4, KKS, | 3.41 | 2 897 | 370 | 2 527 | - |

| | 1999 | 500 | Beruny collector Ayazkala collector | 4.2 | 2 200 | 320 | 1 880 | - |

| Total in the basin (Mm3) | 1990 | 1892 | | 3.98 | 10 205 | 2 202 | 7 196 | 807 |

| 1995 | 1976 | | 3.08 | 12 285 | 2 333 | 9 167 | 785 | |

| 1999 | 1951 | | 4.45 | 11 720 | 2 530 | 8 510 | 680 | |

Return waters in the Syr-Darya River basin (Uzbekistan)

| Catchment | Years of | Catchment | Main | Average | Return | Diverted | ||

| to a river | to | for | ||||||

| Andizhan | 1990 | 277 | Zambarkul | 1.21 | 2523 | 2269 | - | 254 |

| | 1995 | 265 | Karagukon | 1.46 | 2710 | 2440 | - | 270 |

| | 1999 | 280 | | 1.65 | 1264 | 1200 | - | 64 |

| Namangan | 1990 | 268 | Achikkul | 2.21 | | 1010 | - | 1050 |

| | 1995 | 276 | Karakalpok | 1.08 | 2037 | 1030 | - | 1007 |

| | 1999 | 280 | | 2.75 | 2250 | 1090 | - | 1160 |

| Ferghana | 1990 | 349 | Achikkul | 2.21 | 3050 | 2180 | - | 870 |

| | 1995 | 3 | Saridzhuga | 2.28 | 3300 | 2400 | - | 900 |

| | 1999 | 9 | Severny | 2.8 | 2970 | 2020 | - | 950 |

| Tashkent | 1990 | 379 | Urtukly | 1.45 | 2569 | 2329 | - | 240 |

| | 1995 | 397 | Karasuv | 1.29 | 2135 | 1931 | - | 204 |

| | 1999 | 390 | Chilisoy | 2.1 | 2480 | 2200 | - | 280 |

| Syrdarya | 1990 | 298 | Central | 4.19 | 1712 | 743 | 876 | 93 |

| | 1995 | 298 | Golodnaya | 3.49 | 1571 | 831 | 670 | 70 |

| | 1999 | 280 | Steppe Canal Shuruzyak | 3.6 | 1940 | 390 | 1450 | 100 |

| Djizak | 1990 | 2 | Djizak main | 5.6 | 778 | - | 736 | 42 |

| | 1995 | 8 | 4.41 | 1318 | | 1218 | 100 | |

| | 1999 | 5 | 44 | 1165 | | 1100 | 65 | |

| Total in the basin (Mm3) | 1990 | 1856 | | 2 | 12692 | 8531 | 1612 | 2549 |

| 1995 | 1885 | | 3 | 13071 | 8632 | 1888 | 2551 | |

| 1999 | 1890 | | 3 | 12069 | 6900 | 2550 | 2619 | |

Karakalpakstan Republic and Navoy, Samarkand and Djizak oblasts (provinces), continue to capture a relatively large amount of fish from reservoirs of the lower Amu-Darya and the Aidar-Arnasay system of lakes. The densely populated Fergana valley, has a severe fish deficit.

Taking into account the above conditions, the following areas of Uzbekistan appear to have a good potential for the use of irrigation systems for fish production:

| Favourable conditions | Areas with good fish production potential in irrigation systems |

| Social | Namangan, Andizhan, Fergana, Tashkent and Samarkand oblasts |

| Economic | Khorezm, Bukhara, Kashkadarya and Tashkent oblasts; to some degree: Karakalpakstan Republic, Navoy, Samarkand and Djizak oblasts |

| Institutional | Tashkent, Samarkand, Bukhara and Khorezm oblasts |

| Climatic | Fergana valley, Tashkent, Samarkand, Syr-Darya, Djizak and Khorezm oblasts |

| Technological | all oblasts of Uzbekistan |

Difficulties of maintaining and developing irrigation in Uzbekistan negatively affect fish production. Among the factors limiting the use of irrigation systems for fish production are the following:

Institutional constraints. Lack of governmental and non-governmental institutional structures to promote the use of irrigation systems for fish production. Absence of legislation ensuring the rights of private fish farmers to a guaranteed water supply within special limits and to trade in fish.

Economic constraints. Lack of government financing and private investments in the industry. Absence of specialized credit lines.

Technical constraints. Lack of protecting devises on diversion structures which would prevent young fish from being discharged with irrigation water onto irrigated fields; lack of corridors between waterbodies including floodplains, river reaches and canals, to make possible the migration of fish and fish fry from and to places of spawning, reproduction and other types of existence; unsuitable or absence of fish passes; priorities for water use, i.e. irrigation demand and hydropower production, which often do not allow maintaining optimal water supply for fish spawning and in nursery grounds.

Ecological constraints: water pollution in irrigation systems, including increased salinities and toxicity.

Social and cultural constraints. Low level of public awareness that the irrigation network can be used for fish production. Shortage of fisheries experts and of fisheries training programmes.

Some constraints cannot be resolved, therefore fish production should be developed in view of the following constraints: (i) water is regulated only for the needs of irrigated agriculture and/or hydropower production, without inclusion of fishery management requirements for sustainable fish production from irrigation waterbodies; (ii) irrigation systems in Uzbekistan are owned by the government, managed by the government and financed from the state budget. The very low budgetary allocation is slowing down any attempt to use irrigation systems for a sound development of fish production.

The following constraints need urgent attention:

low awareness on the part of central and local authorities of the importance of fish in nutrition of people, and of the potential and economic profitability of fish production. This could be resolved by providing cheap credits and supporting private initiatives;

absence of fish protection devices on water intakes from rivers, canals and reservoirs; the technology is available, simple, and not expensive;

old, no longer appropriate fisheries laws and regulation;

all fish in waterbodies of Uzbekistan, except for fish produced in farm ponds, is state property, including fish in the canals managed by water users;

there are too many government authorities of various levels on which the development of fisheries depends: Ministry of Agriculture and Water Management is in charge of waterbody uses; State Committee of the Environment issues fishing permits; fish landings must be reported to the local authorities;

there is no appropriate body or laws protecting the interests of fisheries. For example, in case of water pollution the damage is measured and levied to the state budget, but fishermen are not compensated for fish losses. Formerly assistance was provided by the Fishery Inspection, which does not exist any more and no alternative organ has been established to carry out its duties;

rise in illegal fishing due to an insufficient government attention being given to fisheries; illegal fishermen are now one of the major fish suppliers to the markets;

in recent years water shortage has limited fish production in the existing fish farms with large ponds; this shows the need for focusing in the future on the use of small ponds and water-saving technologies, which would also be a more suitable approach under the new market economy conditions.

The following constraints may be difficult to address, at least initially. These constraints seem to apply also to other countries of Central Asia:

lack of economical and technological models for the development of private fisheries in irrigation systems;

lack of financial support for scientific and applied research in this direction;

lack of experience in obtaining credits for establishment of fish farms and in attracting foreign participation for private ventures;

lack of international assistance for the development of fish production.

The experience from the period 1960-1980 shows that in Uzbekistan a significant amount of fish can be produced in irrigation systems (canals, reservoirs, drainage collectors, lakes accumulating drainage water). But at present the irrigation systems are hardly used for this purpose as former mechanisms of fisheries management have disappeared, and new mechanisms have not been created. The rehabilitation of fisheries and further progress in this direction will require a number of measures to be taken:

Institutional aspects:

taking into account the institutional integrity of agriculture and water management, establish within the Ministry of Agriculture and Water Resources of Uzbekistan a department for the use of irrigation systems for fish production;

create conditions for involving in fish production the personnel operating and maintaining irrigation systems; this would provide them with additional income and also solve the problem of a rapid employee turnover;

develop a system of public awareness through mass media;

develop the legislative base, precisely setting out the rights and duties of fish producers and protecting their interests;

consider accepting the following institutional framework for fish production: Department of Fisheries under the aegis of the Ministry of Agriculture and Water Resources, Agricultural research organization, Aquaculture associations.

Economic aspects:

utilize favourable conditions arising from on-going reforms in agriculture and water management for development of private small-scale fish businesses in the form of aquaculture in small ponds. Institutionally it could be done within the Associations of Farmers and Water-users.

Technical, training and research aspects:

develop a programme of regular water releases to prevent salinization of waterbodies having good quality water, or to prevent increase in salinity of waterbodies which are already saline, such as Sarykamysh; construct fish protection devices on intake structures; consider the need of fish producers for seasonal flow regulation;

initiate subsequent or simultaneous water use for several purposes, for instance for combining irrigation and drainage with fisheries;

develop strategies for rational use for fish production of irregular and untimely water releases and flood waters;

establish an experimental research centre for development of fishery technologies for use in irrigation systems; the centre would also monitor global development and trends, identify the most appropriate technologies and adapt them for the local geographical, social and economic conditions;

test selected technologies in pilot projects, with the objective of applying them throughout Uzbekistan and in other countries of Central Asia;

develop and establish training courses in aquaculture which would be run by the ICWC Training Centre, Tashkent, Uzbekistan.

Fisheries development in Central Asia has a good potential given the favourable climatic conditions prevailing in this geographical area. This is also supported by the favourable socio-economic setup, with abundance of labour source. The rapid population growth means also increasing demand for food, and a further development and expansion of fisheries is one of the ways which to go.

The available data on water use country by country has shown a significant difference in the use of the total flow for the needs of fisheries (Table 3 and Table 7). For instance, in 1999, 807 million m3 of water or 1.3 percent of its total amount were used for fisheries in Uzbekistan, 61 million m3 or 1.1 percent in Kazakhstan, 75 million m3 or 0.7 percent in Tajikistan, 23 million m3 or 0.01 percent in Turkmenistan and almost zero in Kyrgyzstan. One may conclude that Uzbekistan of all countries in the Region has the best potential for using irrigation systems for fish production.

Table 7

Water use in countries of Central Asia (SIC ICWC data base, Statistics Yearbooks 10-20)

Water use in Kazakhstan (within the Aral Sea basin) (million m3)

| Year | Source | Drinking | Rural | Industry | Fishery | Irrigation | Other | Total |

| 1960 | | 65 | 50 | 100 | 40 | 9 495 | 0 | 9 750 |

| 1965 | | 75 | 60 | 120 | 80 | 10 465 | 0 | 10 800 |

| 1970 | | 95 | 90 | 170 | 150 | 12 275 | 70 | 12 850 |

| 1975 | | 105 | 105 | 200 | 300 | 11 400 | 100 | 12 210 |

| 1980 | | 120 | 130 | 220 | 450 | 12 830 | 150 | 14 200 |

| 1985 | | 126 | 143 | 260 | 590 | 9 736 | 160 | 11 015 |

| 1990 | | 214 | 147 | 276 | 111 | 10 136 | 437 | 11 320 |

| 1995 | Total: | 140 | 130 | 180 | 150 | 10 100 | 600 | 11 300 |

| Surface water | 0 | 30 | 60 | 150 | 10 000 | 285 | 10 525 | |

| Ground water | 140 | 100 | 120 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 375 | |

| Drainage re-use | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 300 | 400 | |

| 1999 | Total: | 54 | 51 | 53 | 61 | 4 701 | 327 | 5 247 |

| Surface water | 0 | 0 | 0 | 61 | 4 666 | 112 | 4 839 | |

| Ground water | 54 | 51 | 53 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 173 | |

| Drainage re-use | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 35 | 200 | 235 |

Water use in Kyrgyzstan (within the Aral Sea basin) (million m3)

| Year | Source | Drinking | Rural | Industry | Fishery | Irrigation | Other | Total |

| 1960 | | 40 | 25 | 28 | 0 | 2 117 | 0 | 2 210 |

| 1965 | | 45 | 35 | 31 | 0 | 2 629 | 0 | 2 740 |

| 1970 | | 55 | 40 | 35 | 0 | 2 850 | 0 | 2 980 |

| 1975 | | 70 | 45 | 44 | 0 | 3 411 | 0 | 3 570 |

| 1980 | | 75 | 50 | 50 | 10 | 3 895 | 0 | 4 080 |

| 1985 | | 79 | 52 | 58 | 11 | 4 070 | 0 | 4 270 |

| 1990 | | 94 | 70 | 68 | 13 | 4 910 | 0 | 5 155 |

| 1995 | Total: | 91 | 85 | 56 | 5 | 4 730 | 0 | 4 966 |

| Surface water | 48 | 20 | 6 | 5 | 4 470 | 0 | 4 549 | |

| Ground water | 43 | 65 | 50 | 0 | 176 | 0 | 334 | |

| Drainage re-use | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 84 | 0 | 84 | |

| 1999 | Total: | 90 | 52 | 44 | 0 | 3 100 | 5 | 3 291 |

| Surface water | 45 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 897 | 0 | 2 942 | |

| Ground water | 45 | 52 | 44 | 0 | 150 | 0 | 291 | |

| Drainage re-use | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 53 | 5 | 58 |

Water use in Tajikistan (million m3)

| Year | Source | Drinking | Rural | Industry | Fishery | Irrigation* | Other | Total | Basin |

| 1960 | | 150 | 250 | 150 | 50 | 6 670 | 250 | 7 520 | Amu |

| 100 | 90 | 40 | 30 | 2 020 | 0 | 2 280 | Syr | ||

| 250 | 340 | 190 | 80 | 8 690 | 250 | 9 800 | Total | ||

| 1965 | | 200 | 400 | 250 | 70 | 7 210 | 400 | 8 530 | Amu |

| 130 | 110 | 60 | 50 | 2 320 | 0 | 2 670 | Syr | ||

| 330 | 510 | 310 | 120 | 9 530 | 400 | 11 200 | Total | ||

| 1970 | | 300 | 580 | 320 | 100 | 8 640 | 500 | 10 440 | Amu |

| 150 | 120 | 80 | 80 | 2 530 | 0 | 2 960 | Syr | ||

| 450 | 700 | 400 | 180 | 11 170 | 500 | 13 400 | Total | ||

| 1975 | | 390 | 640 | 410 | 120 | 7 850 | 600 | 10 300 | Amu |

| 145 | 150 | 75 | 100 | 3 330 | 0 | 3 800 | Syr | ||

| 535 | 790 | 485 | 220 | 11 180 | 600 | 14 100 | Total | ||

| 1980 | | 400 | 650 | 420 | 130 | 8 550 | 600 | 1 0750 | Amu |

| 150 | 160 | 70 | 100 | 3 270 | 0 | 3750 | Syr | ||

| 550 | 810 | 490 | 230 | 11 820 | 600 | 14 500 | Total | ||

| 1985 | | 350 | 620 | 400 | 120 | 7 771 | 552 | 9 813 | Amu |

| 142 | 155 | 65 | 96 | 2 142 | 0 | 2 600 | Syr | ||

| 492 | 775 | 465 | 216 | 9 913 | 552 | 12 413 | Total | ||

| 1990 | | 309 | 563 | 537 | 336 | 7 140 | 374 | 9 259 | Amu |

| 176 | 133 | 57 | 123 | 3 099 | 0 | 3 588 | Syr | ||

| 485 | 696 | 594 | 459 | 10 239 | 374 | 12 847 | Total | ||

| 1995 | Total: | 320 | 402 | 400 | 90 | 8 200 | 40 | 9 452 | Amu |

| Surface water | 170 | 344 | 349 | 90 | 7 920 | 20 | 8 891 | ||

| Ground water | 150 | 60 | 51 | 0 | 200 | 20 | 481 | ||

| Drainage reuse | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 80 | 0 | 80 | ||

| 1995 | Total: | 155 | 183 | 49 | 50 | 2 200 | 0 | 2 637 | Syr |

| Surface water | 5 | 93 | 0 | 50 | 1 510 | 0 | 1 658 | ||

| Ground water | 150 | 90 | 49 | 0 | 400 | 0 | 689 | ||

| Drainage re-use | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 290 | 0 | 290 | ||

| 1995 | Total: | 475 | 585 | 449 | 140 | 10 400 | 40 | 12 089 | Total |

| Surface water | 175 | 435 | 349 | 140 | 9 430 | 20 | 10 549 | ||

| Ground water | 300 | 150 | 100 | 0 | 600 | 20 | 1 170 | ||

| Drainage reuse | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 370 | 0 | 370 | ||

| 1999 | Total: | 490 | 135 | 370 | 50 | 7 050 | 800 | 8 895 | Amu |

| Surface water | 320 | 100 | 330 | 50 | 6 830 | 785 | 8 415 | ||

| Ground water | 170 | 35 | 40 | 0 | 150 | 15 | 410 | ||

| Drainage re-use | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 70 | 0 | 70 | ||

| 1999 | Total: | 250 | 55 | 50 | 25 | 2 000 | 150 | 2 530 | Syr |

| Surface water | 90 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 1 490 | 150 | 1 755 | ||

| Ground water | 160 | 55 | 50 | 0 | 300 | 0 | 565 | ||

| Drainage re-use | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 210 | 0 | 210 | ||

| 1999 | Total: | 740 | 190 | 420 | 75 | 9 050 | 950 | 11 425 | Total |

| Surface water | 410 | 100 | 330 | 75 | 8 320 | 935 | 10 170 | ||

| Ground water | 330 | 90 | 90 | 0 | 450 | 15 | 975 | ||

| Drainage re-use | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 280 | 0 | 280 |

(*) at rayon boundaries

Water use in Turkmenistan (million m3)

| Year | Source | Drinking | Rural | Industry | Fishery | Irrigation* | Other | Total |

| 1960 | | 60 | 25 | 25 | 10 | 7 950 | 0 | 8 070 |

| 1965 | | 80 | 30 | 30 | 15 | 11 345 | 0 | 11 500 |

| 1970 | | 90 | 35 | 35 | 18 | 17 092 | 0 | 17 270 |

| 1975 | | 110 | 40 | 50 | 10 | 22 630 | 0 | 22 840 |

| 1980 | | 130 | 60 | 60 | 15 | 22 735 | 0 | 23 000 |

| 1985 | | 146 | 80 | 135 | 28 | 24 571 | 0 | 24 960 |

| 1990 | | 187 | 42 | 111 | 35 | 22 963 | 0 | 23 338 |

| 1995 | Total: | 330 | 70 | 325 | 35 | 22 470 | 0 | 23 230 |

| Surface water | 145 | 40 | 289 | 35 | 22 274 | 0 | 22 783 | |

| Ground water | 185 | 30 | 36 | 0 | 151 | 0 | 402 | |

| Drainage re-use | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 45 | 0 | 45 | |

| 1999 | Total: | 363 | 188 | 710 | 23 | 16 788 | 3 | 18 075 |

| Surface water | 173 | 148 | 670 | 23 | 16 601 | 3 | 17 618 | |

| Ground water | 190 | 40 | 40 | 0 | 150 | 0 | 420 | |

| Drainage re-use | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 37 | 0 | 37 |

(*) at rayon boundaries

Southern Tajikistan, the flatlands of Kyrgyzstan, the area around the Karakum Canal and northern Turkmenistan have the same climatic, social and economic potential as Uzbekistan. They also have a high percentage of rural population and surplus of labour force and as a consequence a high poverty level. The highest percentage of rural population is in the country with the least developed fisheries, i.e. in Kyrgyzstan, where the rural population makes 73 percent of the total, and Tajikistan, with 69 percent of the total population (Table 8).

Fish yields in Tudakul and Khauzkhan reservoirs reach 60 kg/ha and 30.9 kg/ha, respectively, while in other reservoirs in the region the yields are only 3-7 kg/ha. The development of fisheries in reservoirs serving irrigation will provide employment and contribute to the diversification of food supply. Development of aquaculture in irrigation systems could also result in a manyfold increase in fish supply to markets.

It is estimated that the fish yield potential of lakes, rivers, and reservoirs in the region is about 100 kg/ha/year. This could provide 200 000 tonnes of fish annually to the markets.

Table 8

Distribution of population in the Aral Sea basin (1998) (Statistics Yearbooks 10-20)

| Country | Population | ||||||

| Total | Urban | Rural | |||||

| inhabitants | % of | inhabitants | inhabitants | % | inhabitants | % | |

| Kazakhstan* | 2 710 000 | 6.8 | 7.87 | 1 219 500 | 45 | 1 490 500 | 55 |

| Kyrgyzstan* | 2 540 000 | 6.4 | 19.9 | 685 800 | 27 | 1 854 200 | 73 |

| Tajikistan | 6 066 600 | 15.2 | 42 | 1 880 646 | 31 | 4 185 954 | 69 |

| Turkmenistan | 4 686 800 | 11.8 | 9.7 | 2 109 060 | 45 | 2 577 740 | 55 |

| Uzbekistan | 23 867 400 | 59.8 | 53.2 | 9 308 286 | 39 | 14 559 114 | 61 |

| Aral Sea basin | 39 870 800 | 100 | 25.7 | 15 203 292 | 38.1 | 24 667 508 | 61.9 |

(*) Only provinces in the Aral Sea basin are included

At present there is no regional collaboration for development of fisheries in return waters accumulated in natural depressions. Discharge of drainage water to depressions without outflow has created many lakes and wetlands, the majority of which are shallow. The largest lakes of this type are Sarykamysh and a system of Arnasay lakes. Because of the low discharge capacity of the Syr-Darya River downstream from Chardara storage reservoir (situated at the border between Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan) during the last decade or so water surplus has had to be released into the Arnasay depression during wet years. This usually has happened in winter, as a result of releases from the Naryn-Syr-Darya reservoir cascade. The volume of water in lakes and wetlands formed from drainage water now reaches 40 km3. To ensure that the salinity level is acceptable for fisheries and to protect biodiversity, the water needs to be diluted with freshwater or from time to time flushed out (Fashchevsky, 1996).

The interest of the world in this issue is apparent. Several projects have been partly implemented but discontinued because of lack of funds. These dealt with wetland rehabilitation and drainage water reuse in Uzbekistan (Dengizkul, Kara-Kyr), Turkmenistan (Sarykamysh), Kazakhstan (Kamashbalik, Aktaus, Atsay-Kuvandraya) (Table 9). Other wetland rehabilitation projects are still in progress and are funded by the Global Environmental Facility "Water Resources and Environmental Management in the Aral Sea basin". When completed these projects will assist in the integrated use of irrigation systems as they will contribute to the improvement of hydrological and ecological situation in waterbodies of the Aral Sea basin and to restoration of their biodiversity, including fish production (Ivanov et al., 1996).

While at present no regional networks exist to deal specifically with the use of irrigation systems for fish production, there is a potential for cooperation in the use of irrigation systems for fish production at the regional level. It is believed that the Interstate Coordination Water Commission (ICWC) is a body capable of taking up this function.

Table 9

List of ecologically significant waterbodies and wetlands of Central Asia with transboundary return waters in which maintenance of sustainable regime in the interests of biodiversity is planned for (SIC ICWC data base)

| No. | River basins and countries | Characteristics of waterbodies including wetlands | Flora and fauna | ||

| Volume, billion m3 | Actual volume, billion m3 | Salinity g/L | |||

| Amu-Darya basin | |||||

| | Tajikistan | | | | |

| | Turkmenistan | | | | |

| 1. | Lake Sarykamysh | - | 12-15 | 10-12 | Reed, fish, muskrats, birds of passage |

| 2. | Kette-Shor | - | 0.5-0.6 | 4-7 | Reed, fish, muskrats, waterfowls |

| 3. | Lake Raman-kol | - | 0.3-0.4 | 6-7 | Reed, fish, muskrats |

| 4. | Zengi Bobo | - | 0.5-0.6 | 5-7 | Reed, fish, muskrats, etc. |

| 5. | Tedjen | - | 0.3-0.4 | 4-8 | Reed, fish, muskrats, birds of passage |

| 6. | Golden Century Karakum | 11-13 | - | 5-8 | Fish, birds of passage |

| | Uzbekistan | | | | |

| 7. | Lake Dengizkol | 5.6 | 2.3 | 7.6 | Reed, water vegetation, muskrat, gulls, egret, ducks and other kinds of birds of passage |

| 8. | Lake Solyonoye (Zimbobo) | 0.150 | 0072 | 3.7 | Reed and other types of vegetation, fish, egrets, ducks |

| 9. | Lake Kara-Kyr | 1.3 | 0.740 | 3.0 | Reed and other types of water vegetation, fish and waterfowls |

| 10. | Ayak-Agitma Fall | 7.3 | 3.34 | 2.5-3.5 | Reed, water vegetation, fish, egrets, ducks, waterfowls |

| 11. | Lake Khadicha | 0.3 | 0.135 | 11.5 | Reed, fish |

| 12. | Lake Mashan-Kol | - | 0.250 | 2-2.5 | Haylands |

| 13. | Lake Akhcha-Kol | - | 0.257-8 | 7-8 | Reed |

| 14. | Lake Kara-Teren | - | 0.150 | 4-6 | Reed, fish |

| 15. | Gulf of Djiltyr-Bas | - | 0.130 | 5-7 | Reed, tugay and other types of water vegetation |

| 16. | Lake Sudochye | - | 0.880 | 3-3.35 | Various types of water vegetation, fish, muskrats, and birds of passage |

| Syr-Darya basin | |||||

| | Kyrgyzstan | | | | |

| | Tajikistan | | | | |

| | Kazakhstan | | | | |

| 17. | System of Shieli-Tulekul lakes | - | 0.1-0.15 | 4-6 | Reed, fish, waterfowls |

| | Kuan-Darya | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 18. | System of lakes in deltaic parts of the river in a quantity of more than 150 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 19. | System of Kamyshli-Bas lakes, Raimkol and Tushi-Bas lakes | - | - | - | - |

| 20. | Makpal lake | - | - | - | - |

| | Uzbekistan | | | | |

| 21. | Arnasay fall | - | 28-30 | 4-4.3 | |

| 22. | System of Arnasay lakes | - | 0.15-0.2 | 6-7 | Reed, fish and waterfowls |

| 23. | Tuzkane | - | 1.5 | 6-9 | Reed, fish and waterfowls |

The top level management organizations from the five countries of the Aral Sea basin are represented by the ministers at the quarterly meetings of the ICWC to discuss the current situation related to water distribution and use, and to formulate water strategy for the forthcoming period. The ICWC consists of three permanent executive bodies: BWOs Amu-Darya and Syr-Darya and SIC ICWC. BWOs Amu-Darya and Syr-Darya are in charge of the operational monitoring of the water limits set by ICWC, and of operation of interstate reservoirs and hydrostructures. The SIC ICWC is in charge of technical policy and manages regional information database on regional water resources.

The ICWC is now also paying attention to the interests of other water resource users including fisheries. It aims at overcoming administrative barriers and tries to involve the general public and private sector, non-governmental organizations and water users in the integrated water resources management both at national and regional levels (Dukhovny and Kindler, 1999).

In our opinion, a developed institutional framework for water management at the regional level and the possibility of regular contacts with governments, related ministries and the general public make ICWC the most suitable structure for information support and development of regional network involving the use of irrigation systems for fish production.

The ICWC Training Centre has branches in all countries of Central Asia. It could train employees of water management operational and maintenance services in fish aquaculture and fishery management of irrigation systems. Assistance of international experts, at least initially, would be essential. This concerns especially the development of small-scale fishery business projects. The ICWC could also assume responsibility for the preparation of strategies and technical support for management of sustainable fisheries in transboundary return waters in the Aral Sea basin. Finally, the SIC, as a permanent executive body of the ICWC, could supervise the implementation of pilot projects testing aquaculture potential of various types of waters supplying and arising from irrigated areas.

Anon., 1990. Socio-economic Problems of Aral and Priaralye. Fan, Tashkent. (In Russian)

Anon., 1997. The Main Provisions of Regional Water Strategy in the Aral Sea basin. IFAS, Almaty-Bishkek-Dushanbe-Ashgabad-Tashkent. (In Russian)

Anon., 1998. Biodiversity Conservation. National Strategy and Action Plan. Tashkent.

Anon., 2000. Water Resources, Aral Problem and Environment. Universitet, Tashkent. (In Russian)

Anon., 2001. Rational and Effective Water Use in Central Asia. Diagnostic Report UN SPECA. Tashkent-Bishkek. (In Russian)

Anon., 2001a. Assessment of the Social-economic Damage under the Influence of the Aral Sea Level Lowering. INTAS/RFBR-1733 Project. Final Report. Tashkent.

Dukhovny, V. & Kindler, J. 1999. Developing Regional Collaboration to Manage the Aral Sea basin Water under International and Inter-Sectoral Competition - Water Sector Capacity Building: Concepts and Instruments. A.A. Balkema. Rotterdam/Brookfield.

Fashchevsky, B. 1996. Basics of Ecological Hydrology. Ecoinvest, Minsk. (In Russian)

Ivanov, V. et al., 1996. Review of the scientific and environmental issues of the Aral Sea basin. In: The Aral Sea basin. NATO ASI Series 2., vol. 2: 9-21.

Kamilov, B. The use of irrigation systems for sustainable fish production: Uzbekistan. (This volume)

Zholdasova, M. et al., 1996. Biological basis of fishery development in the waterbodies of the southern Aral Sea region. In: Ecological Research and Monitoring of the Aral Sea deltas: 213-33. UNESCO.