Over the past decades, a variety of different programmes and approaches to working with the poor and trying to improve their livelihoods have been developed by different agencies. Many of these have not lived up to expectations, but much has been learnt about how development activities can be more effective in reaching the poor and bringing about sustainable changes in their livelihoods. More people-centred, participatory approaches to working, and a shift in professional attitudes towards a greater recognition of the strengths and potential of the poor, have achieved much in making development efforts accessible to the people they are intended to benefit. Development workers have also become steadily more aware of the importance of understanding not just the people they want to work with, but also the social, cultural and political context in which they live.

In particular, the importance of the role of local institutions has been increasingly recognized. Many development efforts with the poor have failed or proved to be unsustainable because they have not fully understood these institutions and the way that they influence the livelihoods of the poor. New institutions set up to support the poor have often proved inappropriate or have been undermined by existing institutions that were either not recognized by relevant stakeholders or poorly understood.

Participatory approaches to development, including those commonly grouped under terms such as PRA (Participatory Rural Appraisal) or PLA (Participatory Learning and Action) have done much to improve the ways in which development workers learn about local conditions and identify the poor, as well as understand their strengths and the constraints they have to overcome. But less attention has been paid to ways of understanding the local institutions that shape the environment in which poor people live.

These guidelines aim to fill this gap and help development workers improve their understanding of the role of local institutions. What is it they do? Who exactly do they serve and how? How do they change over time? How can they be strengthened and made more equitable? How can they be made more accessible for the poor?

They are based on the pilot experience of a research programme on “Rural Household Income Strategies for Poverty Alleviation and Interactions with the Local Institutional Environment”. This was set up by FAO’s Rural Development Division in 1998-99 and aimed to develop a new methodological framework for understanding the linkages between rural household livelihood and income strategies and local institutional environments.

The process described in these guidelines has been called an “investigative” process because it aims to generate a better understanding about these linkages. But, as most development workers in the field know, it is impossible to “investigate” rural conditions without changing them. So, as far as possible, these guidelines try to suggest practical ways for development workers to incorporate the process of learning about these linkages into their work. The goal of these guidelines is not research for the sake of research, but better livelihoods for the poor.

To the best of our knowledge, no methodological guidelines exist on how to trace these linkages with the aim of improving the quality, efficiency and sustainability of poverty reduction initiatives[1]. Many of the tools suggested, and used during the research project, are drawn from the “repertoire” of PRAand other approaches to social research.

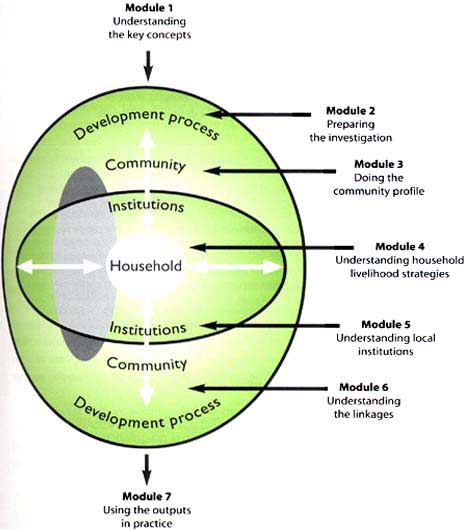

Table 1 reviews the content of the guidelines. This is made up of seven modules, each covering different aspects of an investigation of the linkages between household livelihood strategies and local institutions. The modules are arranged to represent a hypothetical process for undertaking such an investigation.

Table 1 - Content of the Guidelines

|

Modules |

Content |

|

Introduction |

|

|

Module 1 |

|

|

Module 2 |

|

|

Module 3 |

|

|

Module 4 |

|

|

Module 5 |

|

|

Module 6 |

|

|

Module 7 |

|

Figure 1 - Layout of the Guidelines

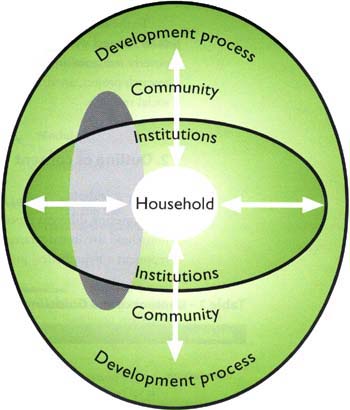

These guidelines are structured around the core elements that are the focus of the investigation: the community, the households within that community and their livelihood strategies, and institutions that may be found at all levels, from within the household to the community and in society at large. The relationships between these elements, and the way in which the different modules of the guidelines address them, are shown in Figure 1.

The order in which the modules are presented is just one possible way of approaching the investigation. It assumes a hypothetical situation where investigators are “starting from scratch” with little prior knowledge or experience of the area and communities they are working in. The guidelines should not be regarded as a “blueprint” to be followed exactly but as a source of ideas that will help investigators to design a study that fits their needs. Users of the guidelines should decide for themselves where their best entry point is likely to be. For example, where information is already available about the communities and households that the investigators are looking at, the community profiles and livelihoods analysis may not be necessary or may require less emphasis and investigators may decide to start off by looking directly at institutions. Whatever the situation, investigators will need to adapt their approaches according to the circumstances they find in the field. Likewise the methods proposed need to be adapted, supplemented and experimented with as they are only intended to represent some of the most common and readily applicable methods, not a definitive selection.

|

THE MALATUK STORY An illustrative story is told in excerpts at the end of every module. This shows how a “typical” group of rural development workers might go about using the guidelines to carry out an analysis of local institutions and household livelihood strategies in the field. This story aims to show users how “real-life” problems and issues might be addressed by practitioners in the field. The symbol in the top-corner of this box is used to show that the box contains a part of this story. The story does not try to describe everything that might be learnt during a “typical” analysis, or all the problems that might be encountered. Neither does it necessarily describe “best practice”. The intention is to give a concrete, if imaginary, example of how the guidelines might be used in practice. The story does not refer to any particular location. Users of the guidelines will almost certainly recognize some elements that apply to their local conditions and others that do not. |

The main users of these guidelines will be professionals working in rural and agricultural development, interacting with field level practitioners. Examples might be:

development agency staff, project staff, consultants and other professionals involved in the design, implementation or monitoring and evaluation of projects, programmes and specific field activities;

district-level staff of rural development agencies and poverty reduction programmes;

backstopping staff working for extension departments and directorates, such as supervisors and personnel involved in training extension agents;

NGO staff and “community facilitators” (who may be part of NGO or government programmes);

training establishments providing courses and sessions that address the institutional dimension of development and training of trainers (TOT); and

researchers, such as graduates carrying out fieldwork to complete their degrees or those on assignments that include an investigation of institutions and organizations.

The language used is intended to be accessible to people at this level, who may not be very familiar with English and may not be used to reading social science literature. A conscious effort has been made to avoid academic terminology and “big words”, and to thus “lower the entry barrier” to the largest extent possible. When relatively “complex” terms are used, they are explained in some detail and examples are given of what is meant. The two main subjects of these guidelines - livelihoods and institutions - are probably the most complex words used and much of Module 2 is dedicated to explaining what these terms mean. Besides these main end-users, other people working in related positions may find these guidelines useful, including:

Middle-level managers of rural development agencies or programmes, for example at the provincial level. They will be able to make use of the guidelines when planning projects and programmes where local institutions play an important role. The guidelines will inform them on what is involved in carrying out an analysis of those local institutions and how they influence and are linked with household livelihood strategies. Managers can thus make informed decisions on how to allocate time and resources for carrying out this type of investigative process and how to design ways of incorporating the findings into ongoing or new development activities.

Policy-makers, who will find the guidelines useful as a means of understanding how conditions at the local level are influenced by policy decisions and how policy reforms are filtered down to rural households through local institutions. The methods suggested aim to improve the communication between development workers and local institutions, and this should also improve the ability of policy-makers to understand “micro-macro” linkages and impacts and take account of them in their policy decisions. The policy dimension, however, is the topic of a separate companion volume (Marsh 2003) to the present guidelines.

These guidelines are not intended for an academic audience. Much has been written on household livelihoods and on local institutions and readers who wish to go into more detail about the issues and definitions involved are referred to the annex and the texts mentioned in the bibliography.

Musa is a social development specialist working for the Malatuk Poverty Alleviation Project (MPAP). The MPAP targets the province of Malatuk, recently identified in a nation-wide poverty profile as one of the poorest areas in the country. Poverty in Malatuk takes many forms and has many causes.

The area is acutely vulnerable to national disasters: cyclones regularly hit the coastal areas, the low-lying hinterland is subject to seasonal flooding while the upland areas to the north and west are drought-prone and environmentally degraded. The MPAP itself has developed out of the relief efforts following a succession of cyclones, droughts and floods that has seriously affected the area over the last decade, destroying infrastructure and, according to some, setting back local development efforts “by at least 20 years”.

Poverty in the area is also blamed on Malatuk’s distance and relative isolation from the main centres of economic development in the nation. Attempts to deal with poverty in the area have not been helped by the government’s current programme of structural readjustment and economic reform. Spending has been cut and the role of government in the delivery of many services drastically reduced. Health, education and transport services still in government hands have all embarked on programmes to recover at least some of their costs, and many other services have been either privatized or abandoned altogether. While this has led to rapid development in certain parts of the country, noticeably the main cities, other primarily rural areas, such as Malatuk, appear to have been largely bypassed, and there is increasing evidence that conditions may have actually become worse for some sectors of rural society. Out migration from Malatuk to the country’s main cities has increased and there is a fear that, if this trend continues, Malatuk could be condemned to permanent exclusion from the social and economic mainstream of the country.

Another key political development affecting the area is the government’s new policy for the devolution of political decision-making and natural resource management to the local level. Elections were held for local assemblies, first at the provincial level and, most recently, at the sub-district level. This is supposed to create more responsive government and greater transparency in the allocation of development resources and decision-making, but exactly how the new local-level government mechanisms are to function has yet to be worked out. There is concern in Malatuk that existing traditional power structures may “hijack” these new local government mechanisms and prevent them from being effective.

The objectives of the MPAP are to address the root causes of poverty in Malatuk. These have been identified as: vulnerability to natural disasters due to poor preparedness and environmental degradation; poor representation of the needs and priorities of the poor in local decision-making bodies; a low level of economic development due to non-availability of appropriate finance; and underdeveloped markets. The project aims to develop an adequate response network to cope with natural disasters, improve the capacity of local institutions to deal with the needs and priorities of the poor, and develop new economic opportunities in the area to stem the out-flow of people to the cities. The current project is to last for five years, but it has been planned as the first in a series of projects, provided sufficient progress is achieved in this first phase.

Musa’s Terms of Reference give her overall responsibility for the social development aspects of the project as a whole, as well as developing a series of sub-projects looking at specific social development issues. These include activities to encourage the development of “appropriate local institutions” to represent the interests of the poor, reduce child labour and enhance the role of women in local decision-making structures.

Musa’s first two months on the project have been spent familiarizing herself with the area and with the project itself. This takes a considerable amount of time, as the project is relatively wide-ranging and complex. Most of her colleagues have technical backgrounds of one sort or another. There are several agriculture specialists, a disaster-preparedness team, a small fisheries group and other specialists in small enterprise development, livestock, cooperatives, transport and marketing. The Team Leader is an administrator but has expressed a special interest in social development issues. In particular, he sees the development of appropriate institutions as being a key element in ensuring sustainable results in all the other fields being addressed by the project. Musa also takes time to get to know the other “key players” in the area - the project’s counterparts in a range of local government departments, the NGO community, and local politicians and representatives.

Several of the technical specialists who joined the project earlier have already prepared sub-projects focussing on technical areas that they have identified as holding potential for development and that are thought to be appropriate for the poor. An effort has been made to consult with local people and identify their own priorities and concerns, but Musa feels the “agenda” of these consultations has been strongly determined by the project’s need to develop particular types of technical intervention and may well have completely ignored more important issues because they were regarded as not being of immediate concern to the project. According to the project design, these sub-projects are to be carried out by the project together with staff from various local government agencies and some NGOs. Some training has already been given to counterpart staff in preparation for these sub-projects, but it is envisaged that most of the new techniques and approaches that the project wishes to promote will be learned “on the job”.

Musa, the team leader and several of their more experienced local counterparts have expressed doubts about this approach. The MPAP is not the first project to work in the area. Past efforts have used very similar approaches only to find, after years of work, that new techniques and technologies introduced by these projects have either not proved sustainable or ended up having little impact on the groups of poor people they were intended for. In the project design, it is stated that the adoption of a more “integrated” approach, involving a range of technical disciplines and government departments, will help to overcome past failings, but it is not very clear how some of the key problems should be addressed. An evaluation of the one recent project - a farming systems development project that worked in the upland areas of Malatuk - identified the persistence of “traditional forms of social organization and institutions” as one of the most important obstacles to sustainable development and “modernization”, but there are no suggestions in the MPAP project document on how this problem might be addressed. This report only looked at the upland areas covered by the project, but there seems to be considerable local consensus that the same is true for much of the province.

To try and understand this better, the Team Leader asks Musa to prepare a study that will look at how these local forms of social organization and institutions influence the livelihoods of the poor. He is anxious to understand how these organizations and institutions might affect different sub-projects that are being planned. As he is also under pressure from the donor and government counterparts for the project as a whole to begin working in the field, he asks Musa to try to get some findings out within a month. From her field experience, Musa knows how complex the study of these issues can be and manages to persuade the project to extend the deadline by an extra month, but she is warned that the other project field activities cannot be held up any longer than this.

| [1] Having said this, we acknowledge

the existence of a number of interesting and complementary research programmes

and invite readers to inform us of other relevant initiatives that we are

unaware of. (Write to FAO’s Rural Institutions and Participation Service,

[email protected]). |