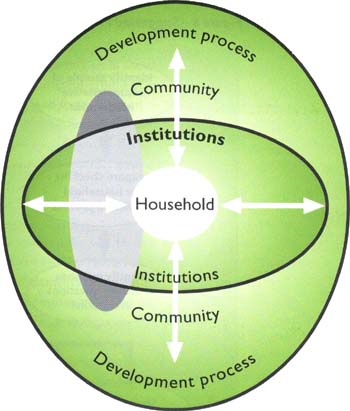

A more detailed understanding of how individual households formulate their livelihood strategies will be a vital part of the investigation. If the investigation starts by looking at institutions, rather than households and their livelihoods, it may be difficult to clearly identify the linkages that matter. Only by looking at the level of the individual household will it generally be possible to understand what the effective linkages are and how they affect people at the ground level. So the process of understanding household livelihood strategies will aim to develop household livelihood profiles that highlight interactions with local institutions.

Not surprisingly, household livelihoods will generally be best understood by talking directly with individual households. This is important in order to understand the interaction of different livelihood assets and household members, the specific factors affecting the vulnerability of the household and the influence of different institutions and processes on these aspects of the household.

The need to look at livelihood strategies at the household level inevitably poses a problem about how to generalize the learning obtained from individual household livelihood profiles. A pragmatic approach to overcoming this problem is needed. It is not feasible to carry out detailed livelihood profiles on a large scale, as they are time consuming and require the use of qualitative, participatory methods. But once detailed work at the household level has identified key issues and elements in livelihood strategies in a particular area, the relevance of these on a wider scale can be checked using more traditional methods on a larger scale.

The overall process that investigators go through for their investigation of livelihoods will depend very much on the time and resources available, but some of the key options and the order in which different activities could be arranged are shown in the pages that follow.

Figure 8 - Suggested Process for Household Livelihoods Profiles

Based on their profile of the community as a whole, the investigating team should be in a position to identify the key livelihood strategies that different groups of households in the community have adopted. The next step is to focus more on individual households and develop detailed pictures of how those households combine the various livelihood assets at their disposal, how they deal with their vulnerability context and how different institutions and processes interact with the various elements in their livelihood strategies.

Deciding whom to talk to

In most cases, the livelihood strategies of households in a community will be too varied for investigators to be able to cover them all comprehensively. There will always be a need to select those combinations of livelihood elements that seem to be most important for the largest number of people in the community. Based on the tables suggested in Module 3 - Doing the community profile, investigators should be able to identify a set of key livelihood “combinations”.

For example, the community profile in a rural, lowland community might have identified four or five principle groups according to the main elements in the community’s livelihood strategies, such as:

farmers cultivating on their own land;

sharecropping on land of others;

agricultural labourers;

small traders;

fishers.

Community profile data should also indicate how these main livelihood elements are combined with other assets and elements within the household to create a complete livelihood strategy. Where these combinations are not yet well understood, the team may need to start working with some of the households in the different livelihood groups they have identified and, in the course of the detailed household interviews, identify how the livelihood patterns of other households nearby may differ so that the team can extend its coverage of households to include a broader range as the investigation progresses.

During the course of the investigation, the aim should be to cover a range of households that are engaged in these principle variations. The sort of sample size that the investigators can cover will depend entirely on the time and resources available. If it is possible to carry out a preliminary survey that allows investigators to identify precisely how many households fall into different categories and then randomly select a sample from these, they can be more confident that the results of their analysis of livelihoods are representative of the community as a whole.

An alternative approach is for the team to regularly meet with focus groups made up of representatives of households from different “livelihood groups” and discuss with them the variations that the team identifies, focussing on how widespread different variations are.

Table 8 - Checklist for Understanding Household Livelihood Strategies

HOUSEHOLD INFORMATION

Household members, sex, age, religion, ethnic group, health status (disabilities, etc.), dependency status, residency status, roles in different livelihood activities

HUMAN CAPITAL

What is the educational status of household members?

What skills, capacity, knowledge and experience do different household members have (training, labour capacity, etc.)?

NATURAL CAPITAL

What land, water, livestock or forest resources do household members use?

What do they use them for?

What are the terms of access (ownership, rental, share arrangements, open-access, leasing)?

PHYSICAL CAPITAL

What infrastructure do household members have access to and use (transport, marketing facilities, health services, water supply)?

What infrastructure do they not have access to and why?

What are the terms of access to different types of infrastructure (payment, open access, individual or “pooled”, etc.)?

What tools or equipment do household members use during different livelihood activities and what are the terms of access to them (ownership, hire, sharing, etc.)?

FINANCIAL CAPITAL

What are the earnings of the household from different sources (income-generating activities, remittances)?

What other sources of finance are available and how important are they (bank credit, NGO support, etc.)?

SOCIAL CAPITAL

What links does the household have with other households or individuals in the community (kinship, social group, membership of organizations, political contacts, patronage)?

In what situations do those links become important and how (mutual assistance, pooling labour)?

VULNERABILITY CONTEXT

What are the seasonal patterns of different activities that household members are engaged in?

What seasonal patterns are there in food supply, income, expenditure, residence, etc.?

What crises has the household faced in the past (health crises, natural disasters, crop failures, civil unrest, legal problems, indebtedness, etc.) and how did it deal with them?

What longer-term changes have taken place in the household’s natural, economic and social environment and how has it dealt with these changes?

POLICIES, INSTITUTIONS AND PROCESSES

What organizations, institutions and associations (societies, cooperatives, political parties, etc.) do household members participate in and what role do they play in them?

How are decisions reached within these organizations, institutions and associations?

Who makes decisions about the use of natural and physical resources in the community and how are those decisions reached (what are the centres of decision-making)?

What laws, rules and regulations affect the household?

One way for the investigators to develop this checklist is for them to take the information on household livelihoods that they have already gathered during the community profile and “fit” it into the livelihoods framework described in Module 1. This can help to highlight what areas they already understand and what questions they still need to ask to improve their understanding.

For developing their livelihood profiles with individual households, investigators need to select whatever methods they feel are most appropriate for the particular households they are dealing with. Clearly, if they can use at least some of the same methods in all their household livelihood profiles, it may be easier at the end to compare different household livelihood strategies. Moreover, much of the most important information will be descriptive and qualitative, and investigators should not feel bound to use a single set of methods right through their investigation. Methods that work well with some households (for example, relatively well-off, educated traders) may be completely inappropriate for dealing with poor, illiterate and marginalized tribal people. Some flexibility is essential.

Whatever approach is adopted, though, it is important to combine a range of methods that will provide a “three-dimensional” picture of household livelihoods. The methods mentioned below may be useful for this.

Structured interviews

Structured interviews can take many forms. They are best used to obtain information where the possibility of ambiguity is limited - for example, basic information about the household, its components, the status and characteristics of different household members and ownership or use of particular livelihood assets.

Structured information sheets can be used to build up a basic picture of household livelihood assets, such as:

natural resources, such as land, water, swamps, ponds, forest areas, grazing land;

livestock;

tools and equipment;

boats and fishing gear;

housing type;

water supply;

infrastructure;

finance;

forms of access to all these assets.

Using these types of “surveys” rather than traditional questionnaire surveys, which also specify what questions have to be asked, has certain advantages. The information required to complete the sheets can be collected at the same time that the semi-structured interviews are conducted, rather than as a separate activity. They leave more liberty to the investigators to decide how they want to obtain the information required and greater flexibility to adapt to the specific circumstances encountered with different groups of respondents.

Semi-structured interviews

Semi-structured interviews are likely to constitute the main method for developing household livelihood profiles. Even if the investigators have decided to develop a more structured survey, they would do well to initiate their work on livelihoods with some semi-structured interviews to give them some initial ideas about what questions they need to ask in their surveys and how to ask them.

Otherwise, much of the information that can be generated from a structured survey can also be obtained using semi-structured approaches. Semi-structured approaches have the advantage of being more flexible and leaving room for the use of a wider range of interview approaches and visualization techniques that should, in the end, generate a richer and deeper picture of household livelihoods. However, because they will generate information that is not always in the same format, it is particularly important that investigating teams be systematic in recording the outputs of their interviews and the learning they generate.

Semi-structured interviews can constitute the frame for most of the other methods discussed in these guidelines, with the various visualization methods being used as tools to facilitate the discussions held during semi-structured interviews. Semi-structured interviews carried out at this stage will generally be carried out either with individuals or household groups.

Focus group interviews and discussions

While semi-structured interviews are likely to constitute the “backbone” of the investigating team’s methods for understanding household livelihood strategies, focus group interviews may have an important role to play. As discussed in Section 2 - Starting out, focus groups can be used as a way of checking on variations between households and deciding how many households constitute a reasonable “sample” if that variation is to be covered. The regular involvement of focus groups can also create a greater sense of “ownership” of the investigation within the community and establish a more interactive relationship between investigators and local people.

These focus group discussions can also contribute to establishing mechanisms that will enable investigators, or the agencies they work for, to continue their learning about livelihoods and institutions after the initial investigation has been completed on other issues that may be of importance in development work, and on project impacts. In the case of agencies or projects that have community empowerment as one of their objectives, the establishment of such mechanisms that involve local people in analyzing their conditions and looking for solutions may well be essential.

Mapping assets

The data collected using these more structured techniques can be expanded upon using an asset map to identify where different assets are located. The same map can then be used to identify and discuss other key assets that households use, including:

infrastructure, such as water supply, transport facilities, health services, markets and schools (describing how these are accessed and what rules and regulations apply to their use);

the location of sources of credit and finance (describing credit arrangements and repayment methods, timeliness with respect to the agricultural calendar, sources of remittances, regularity and frequency);

the location of different organizations and institutions and the households’ contacts with each (describing the roles of those organizations and institutions, their activities and interactions, and the relative importance of each for the household); and

the location of social networks such as neighbourhood groups, age groups, interest groups, religious groups, caste groups, relatives, patrons, middlemen, moneylenders, etc. (describing the relationships with each and their relative importance for the household).

Seasonal calendars

In rural areas, seasonality will usually be one of the key elements affecting household livelihood strategies and the choices that people make about those strategies. A seasonal calendar will therefore be a key tool for talking with respondents about how they make decisions regarding those strategies. Seasonal calendars can be created together with respondents to show:

livelihood activities through the year;

the involvement of different household members through the year;

earnings and flows of income through the year;

patterns of indebtedness;

seasonal changes in food supply;

patterns of migration.

The calendar can then become the basis for focussing on how household strategies are affected by lean periods, or particularly good seasons. Particular attention can then be paid to the role of social networks, organizations and institutions in supporting households during these critical periods, or in the redistribution of agricultural surplus following particularly good seasons.

Timelines

Just as seasonal variations may play a key role in household livelihood strategies and reveal much about the role of local institutions in helping (or failing to help) households to sustain them, responses to particular crises, shocks or episodes of acute vulnerability will also be particularly informative.

Discussions of these events can be helped by a timeline identifying particular episodes in the past, such as natural disasters, epidemics, health crises in the household or other events that have significantly changed the household’s ability to cope.

Once these events have been identified, investigators can ask more questions about:

the household’s responses and changes in strategy following these events;

the involvement of institutions and organizations in helping them to respond;

the involvement of social support mechanisms in response to changes and shocks;

the long term changes brought about by these changes and shocks.

Decision trees

Decision trees are simple visual tools that can help to analyze the steps people take in making decisions and the factors that influence the choices made at each point. They can be particularly valuable when analyzing household livelihood strategies, as they can identify the ways in which different processes and institutions, such as formal or informal rules, laws or social norms, affect the decisions that household members make about using different resources.

Ranking exercises

Ranking exercises can also be used to analyze in detail the role played by different livelihood activities in household livelihood strategies and provide the investigating team with some quantitative indication of the relative importance of different elements. The latter is important because “reliable” data on some of these livelihood activities and the income they generate is difficult to get. Ranking exercises can be useful to analyze:

income levels from different activities;

the contribution of different activities or assets to food supply or income;

the priorities attached to different livelihood activities by household members;

the time devoted to different activities by different household members;

the changes that have taken place in activities over time.

Table 9 - Household Livelihood Profiles - Baraley Village Seasonal Swamp - Fisher Households

|

Principle household livelihood activity |

Type of livelihood capital employed |

Team members |

Visualization tools/form of data available |

Type of respondents |

|

|

Human capital |

Ravi and Musa |

|

Household - men |

|

|

Human capital |

Diane and Musa |

|

Household - men/women |

As in the community profile, the learning generated from the combination of the methods outlined above needs to be recorded in a practical way. Tables similar to those suggested for the community profile can be used to do this. The tables can take, as a starting point, either the same social and professional groups suggested in Module 3 - Doing the Community Profile or other groups of people that have been identified as having broadly similar strategies. The tables developed to review learning about household livelihood strategies will need to cover the basic analysis of the different assets used by households, the vulnerability context and the influence of and on local institutions. The ways in which the learning was acquired and the types of visualisation or data generated to support that particular learning are also tracked, as in the community profile

Examples are provided on the pages that follow. The first table focuses on the analysis of the livelihood assets available to households engaged in particular livelihood strategies. Responses to the vulnerability context in general and to particular episodes that have increased household vulnerability are laid out in the second table. The key area of linkages with local institutions is then approached in the third table. Ideally, the elements in the three tables should be linked - the assets identified in the first table can help to identify the ways in which households have responded to vulnerability (in the second table), and the content of the first two tables can help to identify key livelihood activities for the third table, where they are linked to institutions.

Table 10 - Household Responses to Vulnerability Context - Baraley Village Seasonal Swamp - Fisher Households

|

Vulnerability context |

Livelihood responses |

Type of livelihood capital employed |

Team members |

Visualization tools/form of data available |

Type of respondents |

|

|

|

Human capital |

Diane and Dewi |

|

Household - men/women |

|

|

|

Human capital |

Diane and Dewi |

|

Household - men/women |

Table 11 - Local Institutions Linked with Livelihood Profiles - Baraley Village Seasonal Swamp - Fisher Households

|

Type of household livelihood capital/activities |

Institutions linked with those types of livelihood capital/household livelihood strategies |

Laws, rules and customs affecting those types of livelihood capital/livelihood strategies |

Team members |

Visualization tools/ form of data available |

Type of respondents |

|

Natural assets |

|

|

Ravi and Daniel |

|

Household - men |

|

Social assets |

|

|

Diane and Dewi |

|

Household - women |

|

Human assets |

|

|

Ravi and Daniel |

|

Household - men |

|

Physical assets |

|

|

Diane and Musa |

|

Household - men/ |

|

Financial assets |

|

|

Musa and Daniel |

|

Household - women |

The final outputs of the investigation and analysis of household livelihood strategies should include a detailed profile of key household livelihood strategies, including:

the key activities that make up that strategy;

the key types of livelihood capital that contribute to the household strategy, illustrated by asset maps;

the changes in strategy caused by different factors in the vulnerability context;

the policies, institutions and processes, including local institutions that influence and are influenced by different livelihood activities.

In addition, the team should have a range of data sets and visualizations that can be used to illustrate the different elements in these household livelihood profiles.

Analysis

Analyzing the findings of the household livelihood profile can present particular problems for the investigating team. As in the community profile, it will be important for the team to constantly meet during the course of its field work to discuss findings and update the tables tracking the information. But the volume of information generated during the household livelihood profiles will be considerably more. As a result, it will be important for the team to identify the key learning that its field work is generating. Constant consultation between team members while they are working in the field is one way of doing this. Organizing regular validation workshops involving local people will also be important as it allows the team’s findings to be cross-checked and prioritized.

Where more structured forms of data collection are being undertaken - for example using questionnaire surveys -the time required to enter data into a database and carry out an analysis may make it more difficult for the team to “learn as it goes along”. It can help considerably if the analysis of this type of data has been carefully planned ahead of time - the team should have already identified what sort of outputs it wants from the data and made sure that the database has been set up to allow those outputs to be created. For example, if data from the investigation is being entered into a database, the design of that database should be discussed in detail by the team and whoever will be creating the database. The team should give the database designer examples of the exact tables that it wants to be generated so that the database does not just become a means of storing information but a useful tool that can answer the questions the investigators want to pose.

This means that time needs to be made during the field work for systematically checking data that have been collected, entering them into a database (if one is being used) and carrying out basic analysis while the field work is going on so that any anomalies, problems with the data or particularly interesting findings can be identified while the team is still in the field. If the investigation is being carried out as part of the work of an on-going programme of development, this may be easier as the investigating team may be able to return to the field in the future to check on the results of its analysis. But any team carrying out a study of this kind should bear in mind the need to validate the results of its analysis in the field after the findings have been generated.

Reporting

The information that is generated by the household livelihood profiles will usually need to be summarized into key learning that is directly relevant to the objectives of the study. Other information may have been collected that may be extremely useful in the future. But the large amount of information that can be generated by this kind of study simply cannot all be made accessible within a short time.

In the short term, the priority of the investigators should be to identify those linkages between household livelihoods and local institutions that appear to be most critical for the people in the area. These linkages then need to be demonstrated from the data collected and illustrated with examples so that the next phase of the investigation, the institutional profiles can be planned.

So reporting should be kept brief and relevant. Once again, reference to focus groups in the community who can help the team to validate its findings and make choices about which institutional linkages are of most importance can greatly assist in this process.

Dewi joins the team again to discuss the findings of the community profiles and plan the next phase of the investigation. The team members debate at some length about what they actually mean by “livelihood strategies” and “livelihood assets”. They realize that they have all started out focussing primarily on activities that produce either income, food or goods for exchange. The questions they asked during the community profile reflect this focus. It is Diane who points out that the FAO Guidelines encourage a much broader interpretation of what makes up a “livelihood”. She is concerned that some of the issues that she and Musa have talked about with local women, such as the importance of access to clean water, or the ways in which poorer households in the community are helped by better-off households at times of crisis, may be overlooked if the team focuses too much on things like farming and fishing. Musa understands her concern but is worried about the amount of time that might be required if they try, right from the start, to look at all these different aspects of household livelihoods. In the end, everyone agrees that they need to be careful to take as wide a range of activities as possible into account when they are analyzing household livelihood strategies, but that they will have to use the principal income-generating or income-substitution activities as a starting point for identifying whom they are going to talk to.

Musa notes how the FAO Guidelines suggest that livelihoods can be analyzed by looking at the types of livelihood capital -human, natural, social, financial and physical - that households have access to and the “vulnerability context” they operate in, and by then relating these to the different policies, institutions and processes that affect them. They decide that this framework can form a useful basis for a checklist to use when they are discussing household livelihood strategies with local people and, later, for analyzing their findings.

The team tries applying the framework to some of the household strategies that they have identified so far. In the process they realize that, above all, they have identified activities that use different “natural assets” - land, water, fish, etc. They now try thinking about some of the other aspects of the livelihoods of households they have already talked to during the community profiles. They work through the different types of “human capital”, like education, labour capacity, skills and traditional knowledge, that have come out, as well as the different “physical capital”, like farming equipment, fishing gear or boats, and “financial capital” in the form of savings or traditional credit sources.

For some of the groups they have talked to, they also identify important types of “social capital” that play a role in household livelihoods, like patronage, ties of kinship and different ways that households help and trust each other. They have also identified some of the key elements of what the framework calls the “vulnerability context” - shocks, like the cyclones, floods and droughts that hit the area in past years; and more regular cycles, like the changing seasons, yearly floods or monthly changes in fish availability. The process of applying this framework to what they already know helps them to get a better understanding of what it is they are trying to understand with their livelihood profiles and how they will eventually link with the local institutions they are concerned about.

Taking their cue from this discussion, the team draws up a checklist for the livelihood profiles that will represent the next stage of their investigation. They use the framework suggested in the Introduction of the FAO Guidelines as a way of thoroughly covering all the key aspects of livelihoods they need to consider, but they realize that, when they are actually interviewing people, it may not be possible to follow the precise structure suggested. Instead, the way they put questions will depend on the methods they are using.

For example, if they are asking their respondents to create a seasonal calendar as a means of analyzing their livelihoods through the year, they are likely to start by asking questions about seasonal changes, then ask about activities during different periods, and then ask about the different assets used in different activities. On the other hand, if they are creating a resource map or a resource flow diagram with a household, they need to start by asking about assets and then move on to talking about how those assets change at different times of the year and how they respond to different shocks. But the Sustainable Livelihoods Framework helps them to think through in detail what they are going to talk about in their household interviews.

As they do this, it also becomes clear that many of the linkages between livelihoods and institutions that they are ultimately trying to understand are likely to come out directly during the course of these interviews, so they need to include questions that will draw out these linkages as clearly as possible. They try to come up with a set of simple questions that will encourage people to talk about the institutions that influence their choices about livelihoods. Ravi and Musa’s experience in PRA comes in usefully here, as they use the six key question words: what? who?, where?, when? why? and how? as a guide. The information collected about institutions from these household interviews will then feed into the more detailed institutional profiles they will develop afterwards.

Once their checklist of questions is ready, the team draws up a list of what seem to be “key” livelihood activities in each of the three villages it is investigating. The team members then use the information from their community profiles, particularly the community maps, to identify groups of people that are involved in or concerned with these key livelihood activities so that they can identify a “sample” of households with which to discuss different livelihood strategies in more detail.

As they draw up this list and try to identify locations and specific households that they can talk to about different livelihood assets, they immediately realize that they face a problem about how the different livelihood assets they have identified overlap and the complexity that this might create.

For example, in the floodplain community of Baraley, just looking at farming activities, they come up with a whole range of different livelihood assets. There are three main cropping patterns that represent different farming “strategies”. In addition there are different forms of access to land - ownership, renting or leasing, several different sharecropping arrangements, and “borrowing” from relatives or patrons. There are also those who work as farm labourers, either exclusively or in addition to farming land on their own. The team does not yet understand what the connections might be between cropping patterns, land-access arrangements and decisions about labour, and it is worried that there will not be enough time to look separately at each of these elements they have identified. Besides farming-related activity, the team will have to take into account different fishing activities that people (including farmers) are involved in and a whole range of other activities, such as the collection of reeds for thatching, house construction, operating boats for transport and small-scale trading, that seem to play a more or less important role at different times of the year.

In the end, they agree that they need to identify about ten households in each community that seem to combine as many of the different livelihood assets as possible, but they have to accept that they will never be able to cover the full diversity of livelihoods in each community in the brief time they have available for their investigation. This reminds Musa of the interest shown in their study by her colleagues in the monitoring and evaluation unit, and she starts thinking about ways in which they could use the monitoring and evaluation system from the project to carry on learning and adding detail to their understanding in the future. One idea that they feel they might be able to use in their current investigation, and that might form a useful basis for future work as well, is to hold focus group discussions with people involved in broadly similar types of livelihood strategy and see whether these focus groups might become a regular “contact point” for the project in the communities. They agree that this might constitute a useful “entry point”, particularly as they have already held focus group discussions of this type during the community profile.

The final step in their preparation is to think about the methods they will use with the households they talk to in order to build up a picture of their livelihood strategies. They want to be flexible but agree that there are a few basic sets of information that they should aim to generate with each household. One is a household data sheet that reviews the household components, its basic characteristics, main livelihood activities and education levels, and household asset ownership and access. Another is a map of the households assets, showing where they are located and allowing them to discuss with respondents the arrangements that allow them to have access to these different types of livelihood capital. The team also agrees on preparing a seasonal calendar with each household to show changes through the year and get a picture of the seasonal involvement of different household members in different activities.

These three methods should let them develop a picture of the basic elements in households’ livelihood strategies, but they agree that it may not help them learn as much about possible linkages with local institutions as they would like. So they decide to use decision-trees to analyze with their respondents some of the most important livelihood activities in each household and how decisions are reached about those activities as this brings out some of these linkages they are interested in. They also discuss various forms of ranking exercise they could use to get respondents themselves to analyze what they do for a living and what influences their decisions.

They decide to try out this set of methods with a few households in different villages and then discuss how effective they have been, making any adjustments that seem necessary before moving ahead. Given the history of natural disasters that have affected Malatuk over the last decade, they also decide to talk with their respondents about how they responded to these events. They feel that a timeline would probably be the best method to do this.

In each of the three communities, Baraley, Cosuma and Yaratuk, they assemble focus groups made up of about ten people whom they have identified during the community profile as being involved in key livelihood strategies. For example, in Yaratuk, they gather together two different fishing groups - one of people engaged in seasonal small-scale fishing in the neighbouring swamp (combined with agricultural labour) and another made up of the “gypsies” who collect fish seed for local fish farmers.

Another group is made up of small-scale smallholder farmers specialized in farming the acid soils of the area, many of whom also now have fish ponds. Women who use local wild grasses for making mats and other crafts are also an important group in the community, while small-scale traders make up the final focus group. The team realizes that there will be overlap between these groups, but they seem to provide an appropriate starting point.

With each of these groups, they discuss the next phase of the investigation. They have some information already generated during the community profile and they start off the discussion by reviewing this information. They then ask the participants to focus on the differences between the various households that have the particular livelihood activity in common. So, with the group of “gypsy” fish-seed collectors, they ask what different activities households are involved in besides fish-seed collection. Once they have developed a list of the variations, they use a ranking exercise to clarify the numbers of people within that community who are involved in the different activities.

For the “gypsy” community, this highlights how, at different times of the year, the involvement of men and women, as well as older people and children, changes according to what alternatives are available. Some men have taken to seasonal migration to the city in search of work, generally leaving the women and children to carry on collecting fish seed for local ponds. Others are combining fish-seed collection with the collection (illegally, as it turns out) of various forest produce from the mangrove areas and working for local charcoal producers cutting wood and operating charcoal ovens.

Based on these rankings developed in the focus groups, they identify about five to six different households that seem to cover most of the main variations of livelihood strategy that the group has identified. Some of these are already present in the focus group, but they get introductions to the others and arrange a schedule in each community to cover the households they want to talk to in order to develop more detailed household livelihood profiles.

The team aims to make its interviews with households last, at most, about an hour, but, in practice, the duration is very variable. In some households, all the household members take part and are even reluctant to let the team go. In other cases, people are suspicious and it is difficult to get them involved in the different activities like mapping and ranking.

Some of the poorest households they have identified are particularly reluctant to talk to them. More or less by chance, they find that some of these very poor households seem to prefer to operate in a focus group situation. While carrying out a household interview with a very poor group of people involved in the collection and sale of wild herbs in Cosuma, the members of the household originally identified are very shy and seem reluctant to participate in the interview until they are joined by some of their neighbours, all of whom are engaged in more or less the same activities and live in the same way. The discussion then becomes much more lively. After this experience, they decide that continuing to work in the focus group format might be an option when they are dealing with some of the particularly poor and destitute groups that they have selected for the household profiles. Working in a group seems to give these people more confidence in dealing with outsiders. This strategy turns out to be successful in most cases.

As their work on the household profiles progresses, they find the practice of regularly meeting up as a team to discuss what they are doing and what they are learning especially useful. On several occasions, someone or other in the team has problems with the use of particular methods, and the team talks through how they could be solved. The complexity of the learning that they develop from their household livelihood profiles also means that they frequently need to compare notes.

Often, the information they receive during the livelihood profiles with one group turns out to be directly relevant to what other members of the team have learnt with other households involved in other livelihoods. The tables they develop, based on the ones suggested in the FAO Guidelines, prove particularly useful for identifying these interactions between different sets of information, as well as for keeping track of all the different information and the methods they have used to collect it.

Initially, Musa worries about the amount of time the household profiles seem to take. But she realizes that much of the analysis that would be required at the end of the investigation is in fact taking place during the regular meetings the team holds in the field. These meetings have the added advantage of helping the team to analyze what they are doing as they go along, and this helps to keep the work well focussed. To begin with, the team, now consisting of five people with Dewi, divides into two groups, but as the work progresses, Musa decides that she can spend less time participating in the field work and more time going through the findings and issues. The team also notes that many of the institutional linkages already become clear as it carries out the household livelihood profiles. This means that much of the work during the next phase of the investigation, the institutional analysis, will actually be a question of pulling out and analyzing information already collected and verifying the findings with the institutions involved. The actual field work required for this final phase will be limited to a few more interviews to get more detail about institutions that seem to be particularly important.

The key findings of their livelihood profiles identify a set of key strategies in each community and describe how these strategies are affected by a range of different policies, institutions and processes. As a means of linking these findings about livelihoods to the next phase of the investigation, they take their findings back to the focus groups in each community to discuss them.

These discussions help them to adjust the emphasis they have given to some aspects as opposed to others and allow them to get local people to rank the relative importance of some of the institutional linkages that have been identified. At this stage of the investigation, these focus group discussions prove to be of great importance. Many local people who were still unclear about the real purpose of the study before these meetings, now seem to understand a lot better what it is about and become much more interested. And the investigators come out of these meetings with a clear list of “priority” institutions that they need to look at as part of the institutional profile.