Following concerns that greater liberalization of trade in agriculture might lead to negative effects in terms of the availability of adequate supplies of basic foodstuffs on reasonable terms and conditions, the Marrakesh Ministerial Decision (Annex 1) was adopted. As a mechanism to cope with the possible short-term difficulties in financing normal levels of commercial imports of basic foodstuffs, 17 net food-importing countries made a proposal in the current WTO negotiations for the establishment of a “revolving fund”. This fund is intended to ensure that adequate financing is available to LDCs and NFIDCs during times of high world market prices.

This chapter explores how such a fund could function in the current context of international food trade[18]. The issue of the causality between the WTO reforms and either the level of the prices of basic foodstuffs, or the variability of these prices around their trend is not addressed here. Rather, it is recognized that while foodstuff prices at the moment are lower than several years ago, there always is a risk that they may increase sharply in a relatively short period; and if this happens, then problems in financing normal levels of commercial imports of basic foodstuffs are likely to occur. The chapter describes how a fund to act as an “insurance” against this risk could be set up. Like all other forms of insurance, if the event against which one took out coverage does not occur, the “insurance premium” (the cost of the fund) is lost. As is argued here, the costs of a well-designed fund do not need to be high.

The structure of food imports in developing countries is now radically different from that which prevailed in the early 1990s. By and large, private traders are now responsible for importing food, and financing its purchase. Private traders, though large in local terms, they tend to be weak financially.

Developing country importers normally rely on their suppliers for financing their imports. The suppliers can provide for this in the ways outlined in Chapter XX:

They can arrange for an international bank loan to be put up alongside the food trade.

They can borrow themselves from a bank.

They can obtain a credit or credit insurance from an official agency, which provides cover for 90-95 percent of the risks of the credit.

They can use financial engineering techniques to mitigate country and credit risks, but.

As explained in Chapter III, apart from structured finance, the other three sources of import finance are all limited. Fixed ceilings are difficult to change and other possibilities are limited by a lack of expertise in developing countries.

The current food financing system is not very good for dealing with shocks. If food import needs of a country increase (because of price increases, or greater needs for food imports on commercial terms), it is quite likely that, other things being equal, existing credit lines will be insufficient. People still need food and the market will find a new equilibrium. This would normally have one or more of the following components:

Local traders start rotating their capital and their stocks faster - using the same credit line to import, say, twice as much food (instead of reimbursing over 90 days, they reimburse in 45 days, and buy another cargo). This does not have many negative consequences, but there are some limits to this, imposed by the logistics of international food trade (transport takes much time).

International traders sell more on the assumption that they will place the resulting paper into the forfeiting market. Given the limited depth of the forfeiting market for most developing countries, this will lead to higher discounts for the country’s paper, which is reflected in higher prices charged for the food.

Opportunistic traders looking for high risk/high profit opportunities come in, selling at a relatively high price (and in practice, with a serious risk of delivery of sub-standard commodities or other contractual problems).

Local traders start paying their bills late, using funds due for a credit on one commodity to import another. This will ultimately lead to higher risk premiums, and thus, higher food prices.

International traders do more structured finance deals.

For food consumers, this “market solution” means that food prices are higher than they would have been had financing costs not increased. There are also likely to be short-term supply disruptions, which can also drive up local prices. Governments which provide targeted support to vulnerable groups would be squeezed between a desire to continue targeting their assistance, and pressure to use budget funds to help a larger group of consumers.

The overall balance of payments situation influences the capacity of the private sector to solve financing problems. If there is no surge in export revenues at the same time that food import needs increase, it is likely that the local currency will depreciate, forcing traders to raise local prices, which in turn increases trading risks. The government may also be tempted to intervene in the foreign exchange market, which creates risks for foreign financiers and thus will lead to higher country risk premiums. If export revenues do increase and the overall balance of payments does not deteriorate, these problems are less likely, but financing problems are not necessarily resolved. Those benefiting from higher export proceeds are unlikely to be the same companies that need to procure new financing for their food imports, and the latter would still be faced with the financing ceilings described above.

A new financing facility for food imports, particularly to help countries deal with import shocks, would help the continuing flow of food at a reasonable interest rate. However, given the prevalent system of food imports, a fund that would provide ex-post loans, to help countries replenish the hard currency lost through higher food imports, would have little or no impact on the ability to keep food imports going in times of increased food financing needs.

Local traders who need to import more food need funds, or new credit lines, at once. It is very hard to imagine how the possibility (not even the certainty) that in one or two years, their government will get a new loan will influence the willingness of international traders or banks to give them affordable loans now. It is even harder to imagine that the government would authorize a new, dedicated credit line for food imports without being absolutely certain that the disbursements under this credit line would be refinanced from an international fund - no Ministry of Finance is likely to accept an arrangement of this kind. If there is the certainty that such refinancing will be possible, then the question is why should it take months or years? It should be possible to make funds available at once.

Moreover, if the logic of ex-post payments is purely to replenish the country’s foreign exchange reserves, not to support food imports at the time of need, then there is no point in considering the “food trade balance” in isolation. It would be more logical to consider the balance of payments as a whole.

It is possible to design trigger mechanisms that are sufficiently immediate to enable the disbursement of new food import credit lines at the moment of need. Such mechanisms have the added advantage that they are external to the beneficiary countries, and thus, the actions of the governments of the beneficiary countries need not to be scrutinized; this makes the operations of the food financing facility easier as no policy review function is necessary, and it can considerably speed up disbursement.

Increased financing needs for food imports can result from several factors, some of which are out of the government’s hands, and others which it can influence through its policies:

higher world market prices for food;

a shift from food imports on preferential terms or from food aid, to commercial food imports;

an increased food deficit, as a result of a disaster, bad policies, or other factors.

Donors would have difficulty in accepting compensation to a country for the effects of its government’s poor policies. Increased import needs for such reasons would be compensated only after considerable scrutiny, and financial disbursements linked to serious conditionality. If the cause of the increased needs is a disaster, then there should be more food aid, not loans. It is highly preferable for an international fund to concentrate on the increased financing needs that may result from the first two factors.

In practical terms, import statistics are only available with many months of delay; and even when available, may be an imperfect reflection of the needs for extra import financing, as it may be that in the absence of proper financing facilities, local importers were unable to make extra imports despite larger local needs.

In contrast, information on the first two factors is available with no or little time delay. World market prices for food are available on a real-time basis. Although it would require technical discussions, it should not be difficult to establish, for each country, a baseline price index, and monitor the changes in these indexes. A 20 percent increase in the index, for instance, could then trigger the availability of new funds. Data on preferential food imports and food aid are also available on a reasonably timely basis (donors tend to programme such schemes), and a reduction of the volume of food available under such schemes can in all likelihood be determined in advance. These data are already gathered by existing organizations (in particular, the FAO and the International Grains Council), so it would not be necessary to construct an expensive new monitoring system.

The proposed structure designed to enable financing of food imports when there is a need, rather than to compensate balance of payment losses after the fact, builds on existing practices of international trade and of international finance. The kind of operations described below are familiar to food buyers, banks, and food suppliers, who would have little difficulty in understanding the mechanisms and applying them. The structure of the facility also reflects the fact that the major concern in finance is not so much to find clients interested in borrowing, but to secure reimbursement, and it is assumed that a similar concern applies to donor countries which make funds available or provide loan guarantees. Thus, the structure presented in below contains strong measures to reduce the risk of loan default.

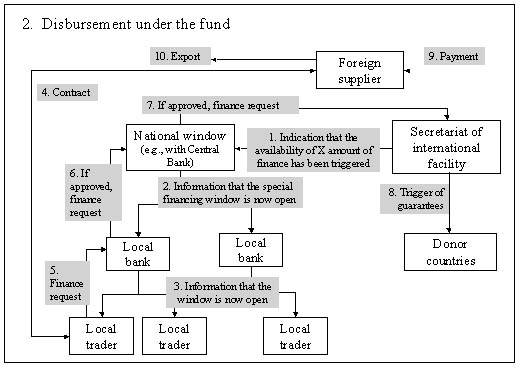

One possibility is the creation of earmarked financing windows in the LDCs and NFIDCs that are interested. These windows would remain dormant as long as certain agreed triggers are not breached, but become active once there is a need for new finance for food imports. A secretariat would be charged with monitoring trigger signals. The secretariat would also elaborate, with interested governments, the trigger levels, and the link between available food import credit and the level reached by the trigger factors, on the basis of clear criteria established by the international community.

To ensure that funds will be available when new food financing is needed, the international community can provide conditional guarantees rather than finance. This implies there is no need to keep a large amount of money in a non-utilized account. At the national level, the government would have to give a sovereign guarantee that any sums borrowed under the facility would be reimbursed. If food imports are a state monopoly, the government could decide that the food parastatal or its parent Ministry administrate the fund. If food imports are largely in private-sector hands, then the actual lending to traders should be through local banks. It would then be appropriate to locate the national window with the Central Bank, which in turn would work with interested local banks to familiarize them with the new window. Local banks would then inform local traders.

A list of reputable international food suppliers should also be established, by the secretariat through international banks with which it will work in the future to distribute the actual funds.

As long as the automatic triggers that the international community has agreed on are not breached, the financial facilities remain dormant. When they are breached, there should be a clear sequence of events to enable traders to obtain the funds necessary to import food. As indicated in the next figure, the sequence of events would start with the international secretariat advising a country that triggers have been breached, and that now, a credit line of a certain amount is available for food imports, and will remain available for a limited number of months.

The local government, if it feels there is indeed a need for more financing for food imports, can then notify the local banks who have agreed to be part of the scheme that the window is now open. These banks, in turn, contact their clients, the local traders. There are then a number of ways for traders to access the fund. The figure shows how it would look if access to the window is on a first-come-first served basis. Another possibility is to auction off access rights among the local traders, for example on the basis of the interest rate they are willing to offer. If access is on a first-come-first-served basis, the local trader would enter into an import contract with a reputable foreign supplier (the list of which should be made available). With a copy of the contract, he now approaches his bank with the request to have the transaction financed - for 80, 90, 95 percent, these details would have to be defined. The local bank would look at the request, and if it is comfortable with the credit risk of the local trader or with the risk mitigation mechanisms that he proposes, the bank will forward the request to the national window. The national window will then send this request on to the international facility, which should automatically make the required payment for the food imports under the contract. This whole process could be finished in a few days.

The international facility could obtain the funds needed in various ways. It could request donor countries to provide funds in place of some of their guarantees; it could borrow from banks against the government guarantees (these give an AAA credit rating, which enables the facility to borrow money cheaply); and in certain conditions, it could raise the funds at even lower cost on the capital market. There are also various ways in which the foreign supplier can be paid. The easiest and less risky approach would be to work through reputable banks, which guarantee that once they make the payment, the food will indeed be shipped in accordance with the contract. Many banks have the skills and experience to do this (in effect, it can be as simple as the opening of a letter of credit), and it would probably not be worthwhile to build up such specific expertise in the secretariat.

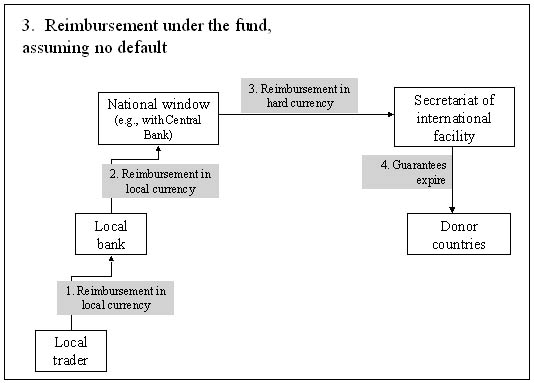

Once the payment has been made, or the foreign supplier feels secure that it will be made, shipment of the food would be arranged, in such a way that the importer pays the supplier the remaining 5, 10 or 20 percent. It would be virtually impossible that the funds could be diverted to other uses. The local trader (importer) then has to reimburse the loan, in local currency (3, above). If he does so in time, the local bank reimburses the national window. Both payments would be in local currency. In theory, loans could be denominated in hard currency, but this would expose the local trader and local bank to risks that can much more easily be managed at the level of the national window. The national window would, in turn, reimburse the international facility for the payment made to the trader; and the international facility could in turn reimburse its source of funds. The donor guarantees could then become dormant again.

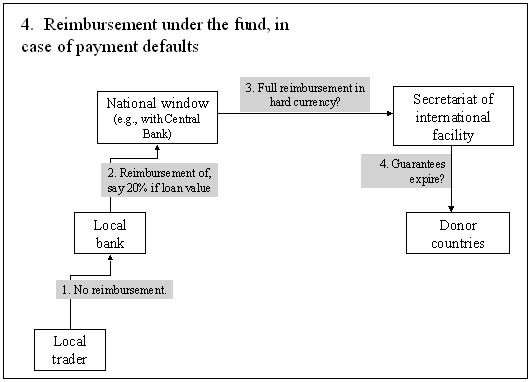

The fund should be set up in such a way that it strongly reduces the risk of non-reimbursement. The best way to do this is to create stakeholders in a proper reimbursement process (4, above). One element in this is that the local banks which actually interact with local traders would have to take a part of the credit risk. If the trader defaulted, the bank would still be obliged to reimburse, say, 20 percent of the loan amount. This percentage should not be too high, because then, the local bank’s credit lines for certain traders or for the food business could be too easily exhausted. But it would have to be high enough to ensure that the bank takes active measures to ensure reimbursement. One of the activities of the secretariat should be to arrange training and advice to local banks so that they feel comfortable with such a role in provide financing to food importers. At the national level, the government would provide a sovereign guarantee, so even if there is a local loan default, the international facility would be reimbursed. If the sovereign defaults, the donors’ guarantees would be called upon. Presumably, this can be handled in the same way that multilateral financiers now deal with sovereign defaults by their member countries. A final element is the use of one of the various instruments that are now available to deal with price risk, which could help to reduce credit risk. If international prices increased, the local trader would have to increase local prices. This could be difficult, and moreover, the government might intervene to reduce consumer prices (e.g. by reducing import taxes). The local trader would thus run a serious risk of making a loss on the transaction, and this would greatly increase the risk of default on the credit. A price risk management component would help local traders to keep prices low, to the benefit of consumers and simultaneously, make default less likely.

It should be noted that governments could have some leeway in deciding on the pricing of food under this scheme. Because interest rate subsidies tend to lead to distortions, it would be advisable to set the scheme up in such a way that traders who benefit from it pay the same interest rates that they would pay in the absence of a crisis situation). The national window would pay a much lower interest charge. The difference could be used in several ways: to set up a mechanism to deal with credit risk, or to subsidize food distribution to vulnerable groups.

A fund as sketched above has several advantages. Extra food imports can take place within weeks of an observed need for new financing for food imports. The use of funds is strictly controlled - diversion of funds is virtually impossible. Risks for food suppliers are minimal, which leads to greater competition among suppliers, and to lower prices. The normal flow of food trade is not disturbed or distorted. Disbursement is easy, with procedures that require little time or documentation. Strong safeguards are built in to ensure loan reimbursement. As the secretariat can be very small and donors would provide conditional guarantees, not funds, the burden on donors’ funds would be minimal. Thus, if there are no market shocks in the years to come, no funds will have been wasted. Finally, a fund like this makes itself superfluous after one or two decades, as its activities to create sufficient capacity among local banks to manage the proper distribution of loans will ultimately lead to these banks being able to give such loans on their own behalf.

|

[18] It follows an earlier

FAO report on the same issue, and has benefited from expert discussions in the

WTO. See FAO, Towards improving the operational effectiveness of the Marrakesh

Decision. Paper prepared for the FAO Round Table on Selected Agricultural Trade

Policy Issues, Geneva, 21 March 2001; WTO. Inter-agency panel on short-term

difficulties in financing normal levels of commercial imports of basic

foodstuffs. Report of the Inter-Agency Panel, WT/GC/62, 28 June 2002. |