It is important to choose a watertight, rat-proof, insect-free container in which crops can be stored for at least nine months. Galvanized steel makes very good silos, but it usually needs to be imported, which requires significant investment. The resulting savings may permit rapid repayment, however, if surplus grain can be sold. Surpluses thereafter are for profit. Most societies have devised some method of storage, but rats and other pests often cause significant losses. In India, losses are estimated at up to 50 percent. Such figures are hard to substantiate, but the author has seen complete stores with every grain lost. The benefits of good storage are overwhelming. Even the use of improved, locally made stores with rat guards made from chicken wire plastered with mud or, preferably, cement would be a major improvement in preserving crops.

FIGURE 5 An improved grain-storage silo made from local materials in Malawi.

Small stores can be made from used 200-litre oil drums. They can be especially useful for storing sufficient seed grain for sowing the following year. A tight-fitting lid keeps out water and insects. Other stores can be made entirely from local materials. Sun-baked mud over pliable sticks woven to make a grain store can be very effective and can be made to a wide variety of local designs. Some are better than others, however, and sharing knowledge of the best techniques pays good dividends.

FIGURE 6 A Bielenberg lever press extracting oil from hybrid sunflower seeds in Zimbabwe.

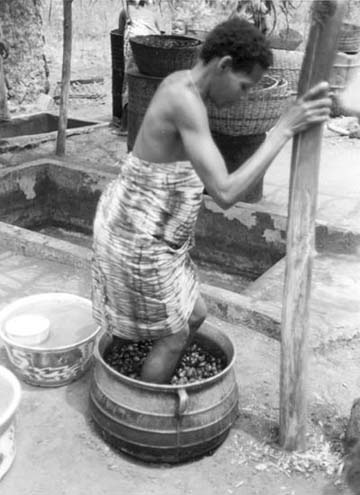

FIGURE 7 Traditional kneading of oil-palm fruitlets after steaming to make oil to be used in a village in Benin.

In recent years, major advances have been made in extracting oil from the fruitlets of groundnuts, sunflowers and palms. The traditional ways of processing these crops - pounding, roasting or kneading - are tedious and inefficient. The Bielenberg lever press, designed to operate manually and replace many of these operations, offers an alternative. With it, one operator can produce 2-3litres of oil per hour from sunflower, copra, sesame and several other types of oilseed. Significantly, this machine is manufactured in developing countries and has proved successful in East Africa and other regions. On a slightly larger village scale, a group of farmers might be able to afford, supply and operate a motorized screw press with the same crops, yielding 15 litres per hour with very little manual labour. With careful filtration, there is even the possibility of using the oil that has been pressed to run the diesel engine. Palm oil is traditionally produced by boiling, kneading and washing. Steaming and pressing in a manual screw press is a simpler alternative. Many such machines are available and made in rural workshops in many parts of the wet tropics. Ground nuts are probably processed best with a bridge press after the nuts have been coarsely ground, wetted and roasted. It is a simple machine that produces up to 3 litres of oil per hour.

FIGURE 8 Traditional washing out of the oil after kneading.

FIGURE 9 Larger-scale palm oil extraction in Benin at fruitlet selection stage.

FIGURE 10 Larger-scale palm oil extraction in Benin using a screw press.

Rice, the staple of Asia, can be stored unmilled until it is required for eating. At that point, a rice mill can remove the hard husk and polish the kernel. This system makes it possible to keep the mill working throughout the year, as long as stocks of unmilled rice remain. Traditional rice processing does not really compete with machine milling, so mill owners will not disturb the local labour balance, although eating habits may be affected. Different types of rice mills are available. National preferences may dictate whether an under-runner disc, a rubber-roll or an Engelberg mill would be the best. This often depends on the ability to share existing knowledge and experience, and the knowledge that support can be obtained quickly if trouble arises. The under-runner disc mill is very popular on the Indian subcontinent, for example, but virtually unheard of in Africa; there is, however, some pressure to adopt the rubber-roll mill, which produces fewer broken grains. If there were no such preferences or constraints, the author would suggest the Engelberg as the best village-scale mill. It is relatively inexpensive, robust and readily repaired. It has few moving parts to wear out and provides an acceptable quality of rice. The skills to operate and maintain this machine can be learned quickly. On the other hand, only the small domestic machines are manually operated; others are driven by diesel motor, which may be too much for some villages. Because a new engine and mill cost about US$3 000, a large sum of money to a subsistence farmer, careful planning is needed.

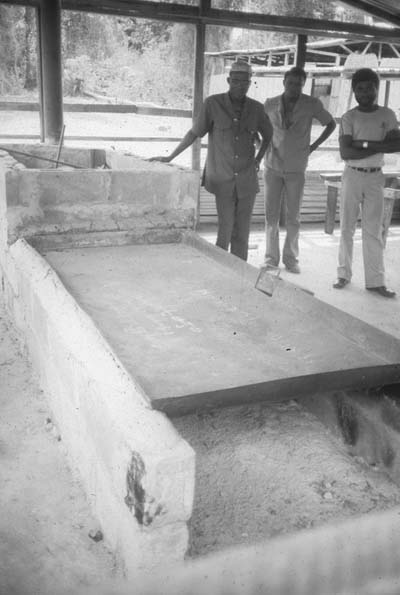

FIGURE 11 Parboiling rice in concrete tanks in Sri Lanka.

Farmers have in general been the most likely people to buy rice mills. They have the raw, unmilled rice, can see the added value that comes from milling the grain and can easily install the equipment on their farms. They can set up a small building and may have access to labour or a family member to operate the mill. They may transfer some of their existing tasks in order to concentrate on the milling, which requires skill in operation and management. Most farmers would wish to keep an item representing such considerable investment under their personal control.

FIGURE 12 Rubber-roll rice mill in Liberia.

Eventually, facilities for parboiling, drying, cleaning or polishing the milled rice can be linked to the enterprise and will add value to the finished product. At this level, the rice can be sold directly into the retail market; unmilled rice is mainly bought by traders.

The maize mill for producing fine flour has been probably the most widely accepted processing machine in Africa because of its obvious advantages over pounding or scrubbing stones. Grain mills can be hand-operated, but can easily be readily motorized, saving a good deal of physical effort. The most efficient manual systems are the plate mill or stone quern, but these are still laborious methods yielding about 5 kg of coarse flour per hour or 1 kg of fine flour. The smallest hammer mill with a 3 kW diesel engine will produce about 150 kg of similar coarse flour per hour or 50 kg of fine flour. The savings in labour are dramatic. The meal is ground through a sieve of fixed size, so the quality is always the same; manually prepared flour can be quite variable. The main choice of machine is between the plate mill and the hammer mill. The hammer mill is the more popular of the two and can be supplied in larger sizes if required; an inexpensive, locally made version is often available with easily fitted spare parts, although certain parts have to be imported. The plate mill is usually only available up to about 7 kW. The whole machine is usually imported, and even the spare parts are difficult to make. The choice of mill often comes down to availability and local preferences. The plate mill can grind both wet and dry products; the hammer mill is confined to dry products. Both machines are capable of grinding a wide range of materials, which may be a means of widening the scope of a business.

FIGURE 13 Locally made plate mill in Nigeria, used for wet and dry products.

Crops can be cleaned more easily by machine than by hand. Perforated-plate or wire-mesh sieves cannot be constructed locally, but they are imported fairly inexpensively and are designed to give a guaranteed product size. Nuts, seeds, grains, coffee, spices and various types of chipped or extruded foods are suited to cleaning by mechanical sieving machines. Many models incorporate a winnowing fan that cleans light material such as chaff or dust from the product by air blast during the sieving process. The output of even the smallest 3 kW motorized cleaner is about 5 tonnes per hour.

Cassava processing lends itself to mechanization for several products, such as dried chips, starch and gari. Gari is a popular food in West Africa and in South America, where it is known as farinha de mandioca. Chips are made by a chipping machine, which usually consists of a large, vertical wheel with coarse serrations or blades on the surface against which the cassava root is held in order to cut off suitably sized pieces ready for drying. This is a simple machine, often locally made, which can be operated by hand, pedal or motor.

Machines are also made for gari production. The crop is washed, peeled, grated, fermented, pressed to remove water, roasted, sieved and packaged. Arange of simple tools and equipment can multiply output considerably. Soil particles are washed off in concrete tanks with running water. The roots are still cleaned by hand, even at quite large factory scale. Attention should always be paid to good seating, correct worktable heights and ensuring regular supply and removal of the peeled roots.

FIGURE 14 Locally made cassava grater in Nigeria.

The knife used to peel the roots should be sharp and of medium length with a good handle, sturdy enough to withstand the constant twisting necessary to lever off the thick peel. The peeled roots can be washed again, in order to remove any soiling from peeling, although this is not always done. The peeled roots can be grated, using one of a range of techniques that yield a good-quality mash. These include the common motor-driven hammer mill, locally made drum graters or even manual graters. The resulting mash is left to ferment for three to five days in non-corroding containers such as polypropylene sacks, fibreglass drums, wooden boxes or stainless steel tanks; the choice affects the investment cost significantly, although the final product is not so different.

The mash is then pressed to remove the water. At village level, this can be done inexpensively with a simple lever system of ropes and wooden beams, or with a more elegant screw or hydraulic press. The latter are usually based on lorry jacks and are therefore readily available and cheap to buy. The cassava mash that comes from the pressing stage is in the form of a cake, which has about 50 percent moisture content and needs to be broken up. Screens, sticks or simple scrapers can be used to do this before it is placed in a roasting pan for preparing and drying the gari. In this process, the starch gelatinizes into a hard, dry powder, which can be stored for up to a year.

FIGURE 15 Large, flatbed gari-making machine in village production in Nigeria.

Roasting can be done in a small bowl or pan for domestic use, but larger bowls are easily managed. At village scale, large flat pans 2-3 m long can be mounted on concrete blocks over a fire, which creates a large, easily managed gari processor. The drying can be done in the same large pan by raking the powder to a cooler part of the pan. These large flat pans can be used to produce up to 500 kg of gari per day.

A cashew nut crop is high in value and lends itself to village-scale operation, although there are some constraints in processing rates. In India, most of the manual processing market is controlled. The skill and speed of the Indian processors and the low cost of labour make it a difficult market to break into; some nuts grown in Africa are exported raw to India for shelling. Cashew nuts are thick-shelled and contain a rather nasty, sticky liquid that is itself of some value. There are small manual tools for decorticating the nuts. After roasting in the shell liquid, the nuts can be cracked open. Small mallets are commonly used and can be operated at the rate of about 10 nuts per minute. About 75 percent of the nuts will remain whole, which makes them more valuable than the broken nuts. In addition to the mallet method, tools have been developed that feed the nuts into a chain system, where they are clamped and a specially designed knife cuts and twists the shell off the kernel; other options exist but are not yet commercially available. Cashew nuts offer the opportunity to introduce a valuable cash crop at village level with very little investment. The supply of raw cashew nuts can be somewhat unreliable, which would not affect a village greatly, but a bad crop could spell the end of a factory that depends on sophisticated automatic equipment and must pay a regular labour force.