1. INTRODUCTION

There are increasing concerns about the precarious condition of world fisheries. The natural evolution of fisheries seems to lead to overexploitation and fishery collapses have become too frequent, including in areas under active fishery management. The overexploitation of world fishery resources has negative consequences on food security, on the socio-economic well-being of communities dependent on fishing and on the ecosystem. This trend towards unsustainability of fisheries occurs despite the fact that the concept of 'sustainability' of the natural resource base has been implicitly or explicitly present in the fundamentals of fisheries management at least since the 1950s

An FAO project has been designed to explore the factors giving rise to unsustainability. The specific objectives set out in the project document are to establish:

1. What are the key factors contributing to fisheries overexploitation and unsustainability?

2. How do these factors interact?

3. Which are the priority issues in addressing fisheries overexploitation and unsustainability?

4. What are the best practical approaches to address long-term concern of fisheries overexploitation and unsustainability?

The project organised a first workshop in February 2002 to address mostly point 1 and partially point 2 above. In preparation for a second workshop, this document summarises FAO Fisheries Report No. 672, the proceedings of the first workshop. This summary covers the workshop report itself, the background documents prepared for the workshop, and individual contributions made by participants in written form, and included in FAO Fisheries Report No. 672.

2. NATURE OF UNSUSTAINABILITY

This section is summarised mostly from Cunningham and Maguire.

Unsustainability is often equated with overexploitation but, although exploitation is doubtless an important factor, the size of fish resources fluctuates from natural causes and a resource may be threatened even in the absence of exploitation. There are indications ((Baumgartner, Soutar and Ferreira-Bartrina 1992) that large fluctuations in stock sizes occurred prior to significant exploitation by human. These fluctuations may be due to natural cycles mediated through climatic changes. Klyashtorin (2001), after having identified 50-60 years cycles in both fish abundance and a climate index, hypothesised that some species thrive during periods of increasing temperature while others do so during periods of decreases. Given that the hydro-climatic conditions change over time, and that each species has specific requirements in terms of temperature, salinity, oxygen content etc., it is not surprising that the abundance, and even the presence of species varies over time for reasons other than fishing. There is therefore no doubt that climate does cause groundfish and pelagic fish stock abundance to vary. But the relative importance of fishing versus climate remains a subject of intense debate in specific stock collapses. The ecological component of the fishery system is therefore dynamic and ecological sustainability does not mean that resources will not fluctuate and that the species mix will remain constant when climatic conditions do change.

Fishery resources are also vulnerable to external threats from human activities of humans which are not concerned with the direct exploitation of the fish resource itself, but which can cause unsustainability, either deliberately or accidentally. Decision makers may consider that the unsustainability of the fish resource is the price to pay in order to achieve some other benefit. However, too often, no explicit consideration is given to the impact of other activities on the sustainability of the fish resource which ends up bearing the cost of other activities. The fish resources face a number of external threats, even if it is not exploited, including habitat losses from coastal area development and land-based pollution which may originate far inland.

Fishing is often simplistically assumed to be the main cause of fluctuations in stock size, with optimal fishing leading to optimal stock sizes, and excessive fishing leading to depletion. Classical examples in support of this view are provided by the increase in stock size of North Sea demersal stocks due to decreased fishing during the two World Wars, rapid rebuilding of stocks after decreases in fishing mortality associated with extension of jurisdiction by coastal States (off the Canadian East Coast in 1977 and off Namibia in 1990), and by a rapid, but ephemeral, rebuilding of the Northeast Arctic cod stock around the turn of the 1990s. But decreases in fishing mortality do not always results in immediate increases in stock sizes as exemplified by the lack of rebuilding of cod on Georges Bank off New England and off the Canadian East Coast.

3. DEFINITION OF UNSUSTAINABILITY

FAO defines sustainable development as "The management and conservation of the natural resource base, and the orientation of technological and institutional change in such a manner as to ensure the attainment of continued satisfaction of human needs for present and future generations. Such sustainable development conserves (land,) water, plants and (animal) genetic resources, is environmentally non-degrading, technologically appropriate, economically viable and socially acceptable" (Garcia 2000).

Therefore, “in FAO definition terms, factors of unsustainability include the non-conservation of the resource base and ill-orientation of technological and institutional change. They lead to degradation of the resource base (including genetic resources) and other changes that are technologically inappropriate, economically non-viable and socially unacceptable, resulting in the non-satisfaction of human needs for present and future generations, (based on FAO Council, 1988).” (Garcia p. 127, Para. 2). Garcia further suggests using past work on sustainability to investigate unsustainability in an analogy with a compass made to indicate the North can be used to go in the opposite direction.

The modern concept of sustainability is seen to have several components. Charles (2001) stresses that “there is wide recognition of the need to view sustainability broadly; in an ‘integrated’ manner that includes ecological, economic, social and institutional aspects of the full system” (p. 186). From bio - ecological and economic perspective, sustainability does not correspond to a unique yield or fishing effort value such as Maximum Sustainable Yield (MSY) or Maximum Economic Yield (MEY) and the corresponding effort. Bio - ecological and economic sustainability can be achieved at any of the fishing effort values on the yield versus fishing effort curve except at the fishing effort corresponding to stock or fishery collapse. Within this modern concept of sustainability, the fishery system should be considered unsustainable when decisions strongly favour one component over the others “i.e. when the functional rules and constraints of the life-supporting ecosystem or the vital needs of the people are disregarded. The unsustainability signal comes in terms of social stress and unrest or ecological stress and resource collapses.” (Garcia, in Gréboval 2002 p. 131, Para. 2)

Working Group 1 of Workshop 1 proposed the following definition of unsustainability: “Unsustainability occurs in a fishery system when it is agreed that there is an unacceptably high risk that the fishery system is currently or will be in some predefined undesirable state. The risk may be aggravated by natural variability. Desirable states, in terms of both human and ecosystem well-being, are defined by society and may change over time.

Unsustainability encompasses:

(1) Acute unsustainability (i.e. collapse of the resource or of the fishery with catches well below what might otherwise be available and recovery may be difficult, slow or impossible);

(2) Chronic unsustainability (i.e. resource reduced to the point where catches are lower than they might otherwise be, even if these low catches might be maintainable indefinitely); and

(3) Incipient unsustainability (i.e. if present practices are continued there is an unacceptable risk that the resource will become acutely or chronically unsustainable).”

4. MAIN FACTORS OF UNSUSTAINABILITY

The background paper prepared by Cunningham and Maguire (in Gréboval 2002) identified important factors of unsustainability and how various management approaches mitigated or amplified the effect of the various factors. At the Workshop, Working Group 1 structured its work in relation to a list of typical methods used in fishery management and how the importance of unsustainability factors varied according to geographic strata, while Working Group 2 based its analysis on the Pressure State Response (PSR) framework of analysis. The geographical consideration of the unsustainability factors described the shape of the importance of the factor from the coast to the high seas. A flat shape meant that there was no geographical component to the factor, a decreasing shape meant that the factor lost importance as the fishery was located further from shore, an increasing importance meant the opposite, and a U shape meant that the importance of the factor was higher close to shore and on the highs seas, but lower in - between.

Inadequate governance, ineffective management controls (including Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated (IUU) fishing), and uncertainty were all considered to have a U - shaped influence. Poverty, lack of alternative employment, low opportunity costs, external threats of harm to the ecosystem, and inadequate risk management were considered to have decreasing importance as the fisheries occurred further from the shore. Other factors of unsustainability were considered to have equal importance regardless of the distance from the coast where the fishery occurs. The factors of unsustainability in the Pressure component of the PSR framework are largely economic (excess fishing capacity, asymmetric entry/exit, market pressures, absence of long term view) and social (no alternative livelihoods, demographic pressures, and poverty). Unsustainability also arises from management and institutional aspects (ineffective and no conflict resolutions). Climatic changes, uncertainty and variability in resources are factors of unsustainability in the bio-ecological dimension.

Working Group 2: Participants were asked to identify the three most important factors of unsustainability for each component of the Pressure State Response framework. The average scores were calculated by weighing individual scores by the rank (1 for 1, 0.5 for 2 and 0.3 for rank 3). The following two paragraphs are extracted from FAO Fisheries Report No. 672, page 15 summarise the results.

“Under the State component of the PSR framework, the main factors of unsustainability are related to the management and institution (ineffective institutions, insufficient monitoring, control and surveillance, insufficient information for decision making and implementation, unclear access conditions, absence of rights, etc.) and to the economic aspects of the fishery system (technological innovations, overcapacity, subsidies, illegal financial transfers). The bio-ecological factors of unsustainability (stock status, uncertainty, variability, fragility) and the social factors (low public awareness, equity issues) are relatively less important.

Under the Response component of the PSR framework, the main factors of unsustainability are related to the management and institutions (ineffective management, undefined rights, inappropriate response from the sector) and social (low public awareness, inadequate organization of the sector). Market responses may be a factor of unsustainability under the economics component of the fishery system. No bio-ecological factors of unsustainability were identified in the Response component, but in the discussion it was noted that uncertainty often undermines management”.

Factors of unsustainability can be internal to fisheries or external; they may contribute directly to unsustainability, or merely be symptoms of other problems and they may have variable importance depending on the stage of the fishery management process or the jurisdiction where fishery management takes place. However, factors contributing to unsustainability are of a similar nature in almost all fishery systems and jurisdictions, if on a different scale and with variable importance.

The Workshop grouped factors of unsustainability into six general types. The following section regroups the classification of unsustainability factors (page 33) and the related recommendations (page 35-37).

Inappropriate incentives, including market distortions: Currently, many fisheries operate in response to incentives (economic and others) that promote unsustainable practices rather than sustainable ones. Inappropriate incentives lead to a short-term view and overcapitalization as exemplified by the race for fish. Lack of transparency and participation of fishers in the management system undermines confidence and willingness to support management measures. Participants in fisheries should be given incentives for long-term conservation and efficiency.

Measures that can give appropriate incentives include: (i) assigning secure rights to shares of fisheries, e.g. in terms of areas, effort units or catch; (ii) using market measures (e.g. certification) to discourage unsustainable fisheries; (iii) allowing all legitimate stakeholders (interested parties) to participate meaningfully in fisheries management including setting objectives, providing input to science, evaluating options and reviewing performance relative to objectives. Meaningful participation will vary geographically and by culture but it should always be transparent and provide full access to information.

High demand for limited resources: Demand for fish is seen as expanding for most markets, with sustainable supply becoming increasingly limited. Higher prices may result which provide an incentive for further input expansion - generally more so in fisheries that are already overexploited.

Fisheries policy must address the need to align the capacity of fisheries to the marine resources available. Appropriate incentives will assist in resolving this problem as indicated above. Governments must consider fully and explicitly the role that fisheries are to play in the macro-economics of their countries (inter alia through setting explicit objectives) and ensure that the role they envisage is sustainable in all the dimensions of sustainability. In particular, great care should be taken with policies that focus on increasing quantities produced, given the resource constraints of fisheries. Attention should also be given to the conflict between internal and external demand and food security.

Poverty and lack of alternatives: Conditions of poverty and lack of employment or livelihood alternatives still occur on a significant scale, particularly but not only, in developing countries.

Use rights should be designed to satisfy societal views of fairness and equity. Benefits from more efficient fisheries management may be used to create alternative employment opportunities. The fishery cannot be expected to solve the problem of poverty and lack of employment. Inadequate management will only make them worse.

Complexity and inadequate knowledge (social, economic, bio-ecological): The complexity of many fisheries systems as well as inadequate information and understanding make it hard to identify proper courses of action.

Fisheries are complex systems with strong and poorly understood interdependencies between social, economic and bio-ecological factors. The knowledge needed to deal with them is largely insufficient. Fisheries authorities should:

- improve data collection (e.g. fisheries statistics) and fisheries monitoring including systems of indicators;

- support sustainable scientific programs for fisheries assessment, formulation of advice, evaluation of policies and management performance;

- promote the integration of fishers’ and scientific knowledge; and

- build capacity for management.

Lack of (appropriate/effective) governance: (conflicting objectives, lack of attention, will and authority): The inability to implement required management measures by legitimate authorities (including the absence of appropriate institutions) contributes to unsustainability.

Consistent with a precautionary approach, participants in fisheries management systems should assess the uncertainties and adopt appropriate measures to address the inter-related risks in the economic, institutional, community and ecological dimensions of sustainability.

Institutional sustainability is a component of the overall concept of sustainability. Fishery management institutions should be appropriately funded, possibly through revenues generated by the fishery itself. Under appropriate conditions, delegation of selected management functions to local institutions can be promoted.

Participation of interested parties at all stages of the management process should be ensured. Fishery authorities should promote capacity building and increased public awareness of the need for conservation and management, including for policy makers and the general public.

Local, regional, national and international fisheries management bodies must be provided with adequate resources for monitoring, control and surveillance (including law enforcement) to fulfil their mandate and functions effectively.

The performance of new and existing management approaches and measures should be evaluated over time in order to assess their effectiveness in achieving the intended objectives and to promote institutional learning.

International financial and technical assistance institutions should ensure that their resources do not contribute towards unsustainable fisheries. This should occur consistently and be harmonized at the various levels of governance.

In areas where fishery management institutions do not exist, e.g. in the High Seas, they should be created by the governments concerned so that all the world’s marine areas are managed by management institutions.

Where fisheries management institutions exist (or are created), these should be strengthened sufficiently to be able to play their necessary roles. This strengthening should include, as a minimum, receiving clear legal authority to manage and conserve fisheries resources; receiving both the mandate and the resources to ensure compliance with management and conservation policies and regulations; having effective dispute settlement mechanisms in their legal structure; regular performance evaluation of their policies in achieving their objectives.

Donors and international financial communities should actively promote and assist the participation of developing countries in regional fisheries management organizations so that their participation ensures the achievement of the objectives of those organizations.

Interactions of the fishery sector with other sectors, and the environment: These factors are in most cases beyond the control of the fisheries sector but need to be better accounted for. Government departments responsible for fisheries must take a lead role in protecting the fishery, the resources, and their habitats, from external threats of pollution and contaminants, habitat damage, etc. and in ensuring that the fisheries sector is recognized as a legitimate user in coastal areas.

5. PATHS TO SOLUTION

Linked with the above factors of unsustainability and recommendations, the Workshop identified seven types of measures that could be taken to address the factors of unsustainability. These paths to solutions are presented as steps towards sustainability.

- Rights: The granting of secure rights to resource users (individually or collectively) for use of a portion of the catch, space, or other relevant aspects of the fishery.

- Transparent, participatory, management: The granting of a meaningful role to stakeholders in the full range of management (e.g. planning, science, legislation, implementation).

- Support to science, planning and enforcement: Providing the resources necessary for all aspects of management of the fishery.

- Benefit distribution: Using economic tools to distribute benefits from the fishery to address community and economic sustainability.

- Integrated policy: Planning fisheries, including setting explicit objectives that address all the dimensions of sustainability and the interactions among the factors of unsustainability.

- Precautionary approach: Application according to FAO guidance.

- Capacity building and public awareness rising: Development and application of programmes to better inform policy makers and the public at large about main fisheries issues.

- Market Incentives: Using market tools in situations where they are appropriate for addressing factors of unsustainability.

The Workshop also provided a table listing the main factors of unsustainability in the left hand column and possible paths to solutions in the right hand column.

|

Main factors of unsustainability |

Paths to solutions (with indicative linkage to relevant factors) |

|

1. Inappropriate incentives |

Rights (1) |

6. FISHERY MANAGEMENT INSTRUMENTS

Several international instruments are dealing with aspects of ocean governance. A review is provided by Lodge (in Gréboval 2002). The recommendations relating to the relationship between factors of unsustainability and international fisheries instruments identified by the workshop (p. 40) are reproduced below.

International fishery instruments address directly or indirectly many of the factors of unsustainability in fisheries and reveal a high level of consensus at the international level on the factors to be addressed. A major problem is one of failure to implement existing instruments. More guidance and capacity-building activities should be directed at the implementation of international instruments at national, subregional and regional level.

The workshop concluded that the key international fishery instruments would benefit from a more detailed analysis and assessment against a more precisely-defined list of factors of unsustainability, but that such a study should also identify specific weaknesses in the current international framework, especially relating to the management of high seas resources (other than straddling and highly migratory stocks) and propose solutions. Among the weaknesses in the current regime identified by the workshop were the problems of effective management of exclusively high seas resources, effective enforcement by the flag State and the effective implementation of internationally-agreed market-related measures.

The workshop noted that the focus of many of the international fishery instruments is on action at the regional level, primarily through regional fishery bodies. In the case of straddling and highly migratory fish stocks, the UNFSA establishes the regional fishery management organization as the primary mechanism through which States should fulfil their obligation to cooperate in conservation and management under the 1982 Convention on the Law of the Sea.

The workshop further noted that some of the existing regional fishery management organizations are ineffective, while others have not yet successfully addressed key factors of unsustainability including those relating to compliance, illegal, unregulated and unreported fishing, effective decision-making, the provision of independent scientific advice in accordance with the standards established in international fishery instruments and the implementation of internationally-agreed market-related measures. Among the specific constraints to the effective operation of some regional fishery bodies are lack of resources and lack of effective participation by members, particularly developing countries. Additional efforts should be directed at addressing these constraints.

In order to promote effective implementation of international fishery instruments at subregional and regional level, the workshop considered it was necessary to strengthen regional fishery bodies to ensure that they:

(a) meet the standards established by the relevant international fishery instruments;

(b) possess the necessary mandates to enable them to address the factors of unsustainability; and

(c) are equipped to carry out the functions ascribed to them, including by having an adequate resource base and by providing mechanisms for effective participation in their work by all members.

7. CONCLUSION

Cunningham and Maguire (in Gréboval 2002) concluded “that without some form of explicit institutional arrangement, either through local or national institutions, fisheries will progressively become unsustainable, at least under one component. In general, they will become economically unsustainable before ecological unsustainability becomes a possibility, but there are cases of low productivity species (deep water slow growing species) where exploitation rates may increase sufficiently rapidly for the fisheries to remain economically sustainable while being biologically unsustainable. Also, low productivity species may become threatened even as by-catch species.” Appendix 1 provides a description of the dynamics of overfishing in the absence of management.

Boyer and Hamukyaya (in Gréboval 2002) provide an informative account of the development of the orange roughy fishery in Namibian waters showing that fishery management is not always a guarantee that sustainability will be achieved. “Assessment and management created a paradoxical situation whereby state-of-the-art assessment and modelling yielded high quality advice, yet the fishery virtually collapsed within a very short time. There was close cooperation with industry at all stages. A number of strategies for dealing with uncertainty were incorporated into the stock assessment, including a Bayesian approach, and management process, and attempts were made to apply the precautionary approach. In addition, adaptive management was applied through institutional learning. As a result there should be some lessons to be learned from the assessment and management of orange roughy in Namibia. Some aspects provide good examples of how a new developing fishery should be managed; others are clearly illustrative of procedures to be avoided. In particular, one of the main reasons why the management of orange roughy failed to prevent stock collapse was underestimation of some of the uncertainties, particularly those reliant on basic understanding of the biology and behaviour of orange roughy.” (Boyer and Hamukyaya p. 148, Para. 1).

Cunningham and Maguire (in Gréboval 2002) believe that the almost exclusive focus on bio-ecological sustainability probably contributed to the perceived limited success of fishery management. Fishery management was expected to rebuild all stocks of predators and preys to their optimal sizes and maintain them there. This was overly ambitious and it neglected the possible impact of climatic variability (whether natural or induced by human activities), multispecies and ecosystem effects. They suggest that it could be preferable to act on those components of sustainability where fishery management is likely to have a more direct effect, i.e. the socio-economic, community and institutional components.

McConney (in Gréboval 2002) supports this view and suggests (p. 151) that “Emphasising human individual, institutional and societal flexibility and adaptation to change, whether humans or other components of nature cause the change, can provide alternatives to rigid or mechanistic perspectives on sustainability. First, humans could be seen as more integral than external to ecosystem models. Ecosystem and human system integration is implicit in holistic treatment of sustainability. Achieving sustainability of fisheries-based livelihoods, for example, may well lead to rational short-term over-exploitation of fisheries resources with the expectation of medium to longer-term recovery to sustainable levels. This may not be bad in some specific cases and for certain fishery resources, but it seems much worse if the ecological and human systems are seen as separate, and perhaps conflicting.”

“The institutional arrangements with the highest probability of avoiding the three components of unsustainability are those involving meaningfully interested parties in the decision-making process but also in the implementation, and to develop an appropriate incentives structure. Command and control approaches have, therefore, limited potential outside of very specific situations. Therefore, co-management appears a promising approach, whatever method of management (technical conservation measures, input controls, overall output controls, use rights, market measures) is chosen.” (Cunningham and Maguire 2002, p. 80).

Modern fishery management has become closely associated with harvest control rules, in a control theory context. Saila (1997) notes that although “conventional control theory has been a tremendous success where the system is very well defined, such as in missile and space station guidance” the theory is perhaps not appropriate to control complex systems such as commercial fisheries because the precise structure of the system is virtually unknown and that there are no reliable models of the process to be controlled. Consistent with McConney above, he suggests that success in fishery management requires a system that can handle qualitative information and uncertainty, in a straightforward, transparent and not computationally intensive manner. This is not the direction in which most fishery management processes are heading.

The final paragraph of Cunningham and Maguire summarise the problem succinctly: “No fishery management system aims at unsustainability. Yet, it is rarely possible to avoid all of its components: when ecological unsustainability is avoided, it is often at the expense of the other components, and vice-versa. Does this mean that all fisheries are going to eventually become unsustainable under some or all of the components of sustainability? Or is unsustainability a normal statistical expectation of the fishery management system failing some of the time? Is a given percentage of unsustainable fisheries a normal feature of a given fishery management system due to the slowness of the control and feedback mechanisms?”

REFERENCES

Baumgartner, T. A., Soutar, A. & Ferreira-Bartrina, V. 1992. Reconstruction of the History of Pacific Sardine and Northern Anchovy Populations over the Past Two Millennia from Sediments of the Santa Barbara Basin, California. CalCOFI Reports. 33: pp. 24-40.

Charles, A.T. 2001. Sustainable fishery systems. Fish and Aquatic Resources Series No. 5, Blackwell Science, 370 pp.

Garcia, S. 2000. The FAO definition of sustainable development and the Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries: An analysis of the related principles, criteria and indicators Mar. Freshwater Res. 51: pp. 535-541

Gréboval, D. (ed.). 2002. Report and documentation of the International Workshop on factors contributing to unsustainability and overexploitation in fisheries. Bangkok, Thailand, 4-8 February 2002. FAO Fisheries Report No. 672, Rome, FAO.173pp.

Klyashtorin, L.B. 2001. Climate change and long term fluctuations of commercial catches: the possibility of forecasting. FAO Fisheries Technical Paper. No. 410 (in press).

Saila, S.B. 1997. Fuzzy control theory applied to American lobster management. In “Developing and sustaining world fisheries resources: the state of science and management”. Second World Fisheries Congress proceedings.

APPENDIX

UNSUSTAINABILITY DYNAMICS WITHOUT MANAGEMENT

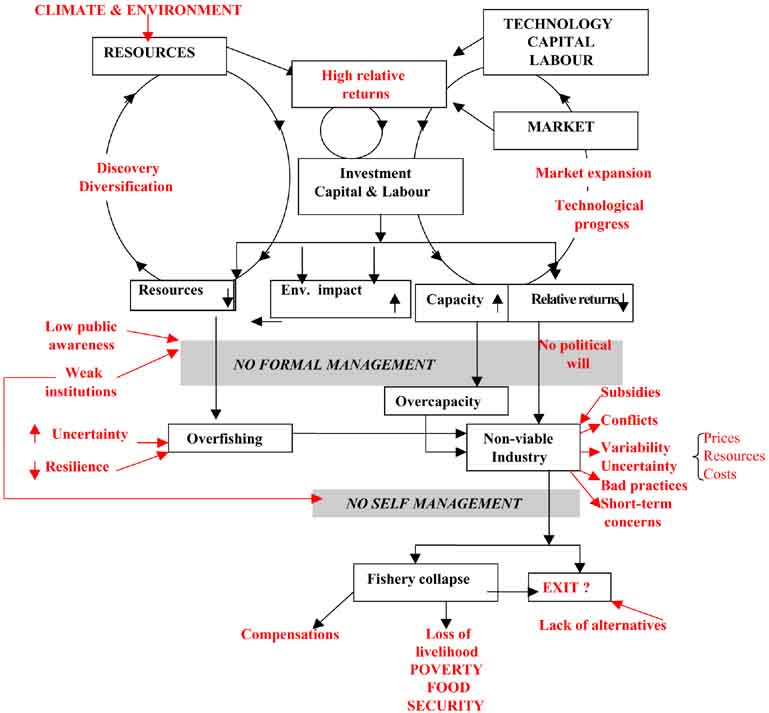

There are several reasons why fisheries management may not be in place. In early stages of the fishery the reason may be that no problems emerged which may have called for management. However, the more typical situation is that management institutions are weak. The institutions may lack capacity to produce the knowledge required, to resolve conflicts and have decisions made or to implement management measures through monitoring, control and surveillance or other law enforcement measures. Such weaknesses may apply both to individual partners in management (government, fishing industry and communities, other interested parties) and to the institutions through which they interact.

Several driving forces may motivate people and capital to move into the fisheries sector. Markets, available fisheries resources and technological opportunities may enable investments in the sector to produce a profit which is above the expected profit for alternative investment opportunities. Likewise, poverty or low incomes in other sectors may be such that labour expects to be able to produce a higher income in the fisheries sector than elsewhere, whether in kind or in cash.

These higher relative returns in the sector will, if there is no management, put pressure on the sector by attracting capital and labour into the fisheries. This increase in capacity results in higher exploitation of the resource that leads to a reduction in the resource biomass. In terms of economics this results in lower catches relative to the invested capital and applied labour, and thus lower returns. As a side effect, increased capacity will lead to increased environmental impacts in terms of by-catches and impacts on the habitat. Furthermore, as the resource is being more exploited, uncertainties about its state and productivity may increase and environmental variability will result in larger variability.

Lower returns will motivate the fisheries to compensate by expanding the market (expanding market volume, finding higher value markets), reducing relative costs through technological innovation or to expand the resource base by exploiting other resources. If such means are effective in maintaining relative returns above what is expected in other sectors, the influx of capital and labour is expected to continue. The results of this process will, if unchecked, result in recruitment-overfishing that eventually may lead to the stock being depleted or even collapse. In this process, the relative economic returns will become so low that the industry basically is unviable. This will create conflicts among users and increased motivations for bad practices.

Alternative income sources for specialised labour may not be available and investments are locked in vessels with a long investment horizon. The situation may, therefore, be that labour and capital remain for a long time in the fisheries even at relative rates of return which are considerably lower than returns in other sectors. This lack of exit options perpetuates and aggravates the overexploitation and the deterioration of the economy of the sector.

Figure 1: Dynamics of unsustainability under NO MANAGEMENT option