I. LARGE VOLUME SMALL PELAGICS

1. THE LARGE VOLUME SMALL PELAGIC FISHERIES OF THE SOUTHEAST

ATLANTIC: ANGOLA, NAMIBIA AND SOUTH AFRICA

By David Boyer and Helen

Boyer

2. THE MANAGEMENT OF THE SMALL PELAGIC FISHERY IN CHILE

by

Alejandro Zuleta V.

II. TUNA AND TUNA-LIKE SPECIES

3. BIOLOGICAL OVERVIEW OF TUNAS STOCKS OVERFISHING

by Alain

Fonteneau

4. MANAGEMENT OF TUNA

by Judith Swan

III. LARGE VOLUME DEMERSALS

5. THE BRITISH COLUMBIA ROCKFISH TRAWL FISHERY

by Jake

Rice

6. LARGE VOLUME DEMERSAL FISHERY IN THE NORTH ATLANTIC

by

Jean-Jacques Maguire

7. THE GULF OF THAILAND TRAWL FISHERIES

by Ratana

Chuenpagdee and Daniel Pauly

IV. COASTAL FISHERIES

8. THE MANAGEMENT OF MEDITERRANEAN FISHERIES RESOURCES -

COASTAL FISHERIES IN ITALY

by Massimo Spagnolo

9. THE MANAGEMENT OF MEDITERRANEAN FISHERIES RESOURCES -

COASTAL FISHERIES IN THE MEDITERRANEAN REGION

by Alain Bonzon

10. WEST AFRICAN COASTAL AND SMALL-SCALE DEMERSAL

FISHERIES

by Stephen Cunningham, Boubacar Ba, Sidi el Moctar ould

Iyaye

11. THE CASE OF DEVELOPING COUNTRIES

by Philippe

Cacaud

Summary

The factors leading to unsustainability are discussed in relation to the large-volume small pelagic fisheries of the south-east Atlantic. Namibia has a fisheries management system that incorporates many of the accepted best-practices as outlined in the major international fisheries conventions. The South African management system is very similar, while, owing to several decades of civil war, the Angolan system is still in the early stages of development. Despite the similarity in the management systems of South Africa and Namibia, Namibia’s sardine and anchovy stocks are in a severely depleted state, while, in contrast, South Africa’s stocks are fully recovered. Furthermore, in addition to having an acclaimed management system with generally effective control and enforcement, the Namibian bio-ecological system is also seemingly conducive to successful fisheries management. The system contains relatively few species and is clearly defined, with few shared or straddling stocks. The state of the Namibian small pelagic stocks clearly indicates that current fisheries management systems are not effective at managing highly variable and dynamic fish stocks and it is therefore, concluded that external effects also play a significant role. Until these are understood, and incorporated into management policies, unsustainable fisheries are likely to recur.

1. BACKGROUND

This review focuses on the large-volume small pelagic resources of the southeast Atlantic, a region that has seen massive political and social reforms during the past decade. It, therefore, begins with a brief review of the socio-economic climate within which the current fisheries management systems have developed (Section 1.1). This is followed by a short description of the major fish stocks and fisheries and the international agreements that the three countries of the region are party to (Sections 1.2 and 1.3). The main body of the review describes how the management strategies of these countries relate to the various international fisheries management instruments (Section 2). Finally the two questions posed in the analytical framework are addressed, namely whether fisheries management has been successful and what in terms of international instruments needs to be done to reduce unsustainability (Sections 3 and 4).

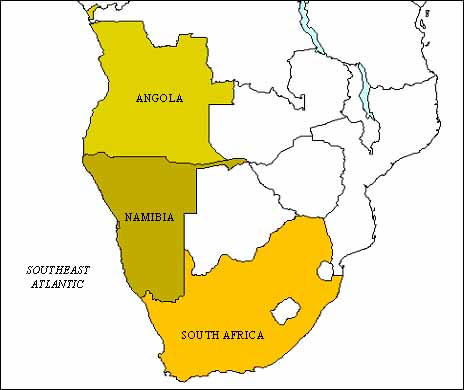

While the review covers the three countries of the southeast Atlantic, Angola, Namibia and South Africa (Fig. 1), information relating to Angola is difficult to obtain and therefore, many of the examples are taken from Namibian and South African fisheries. When a single example has sufficed, this has generally been taken from Namibia, as the current fisheries regime is more mature in that country and the authors are more familiar with this system.

1.1 Socio-economic climate

1.1.1 Angola

Angola is emerging from more than two decades of civil war following Independence in 1975 and is considered a “least-developed” country. National priorities have therefore, been focused on other issues and until recently fisheries have received limited official support. The fisheries sector is an important component of the economy, being third after oil and diamond mining; although in terms of exports this amounts to less than 1 percent of total exports compared to 70 percent for oil.

Figure 1. The countries bordering the southeast Atlantic

Fishing provides half of the animal protein of the country, and annual per capita fish consumption is the highest in the SADC[12] region; 40 kg in coastal regions, 10 kg inland and 16 kg overall (BCLME 2002). It is an important source of employment for coastal communities, especially the poorer sector of society, and although the artisanal sector only accounts for around 18 percent of the landings, over 60 percent of the estimated 35 000 fishers are employed in that sector (SADC 2002).

The current potential of Angola’s fisheries has been estimated at around 360 000 tonnes per year, of which 285 000 tonnes are small pelagics (SADC 2002). In 1999 around 200 000 tonnes were landed, with the purse seine catch dominant at 80 000 tonnes (SADC 2002). Most was caught by the national fleet with only 32 000 tonnes caught by foreign vessels. Although only five percent of the catch is exported, about half of the revenue comes from exports, with prawns accounting for roughly half of this (BCLME 2002). The contribution of fisheries to GDP was estimated to be between three percent and five percent in the latter part of the 1990s (SADC 2002).

The authorities generally lack the capacity, both in terms of manpower and finances to effectively manage the fisheries resources. Until recently fisheries issues have been low on the political agenda, largely because of the pressing priorities elsewhere, but possibly also due to the relatively low importance of fisheries compared to the considerably more valuable mining industry. There are some indications that as the country normalises that political will is starting to address urgent fisheries management issues.

1.1.2 Namibia

Namibia gained Independence in 1990 and the newly elected government inherited severely over-fished stocks of all commercial species. The authorities, realising the potential value of fisheries to the fledgling post-Independence economy, implemented aggressive policies to re-build the fish stocks. Research was initiated with support from foreign donors, an effective monitoring, control and surveillance regime was implemented and a legal framework to facilitate these initiatives was enacted. Indeed the Namibian constitution is the first in the world to include sustainable utilisation of natural resources (Brown 1996), and this led to the necessity for the enactment or reform of a number of Acts that seek to conserve Namibia’s natural resources, while promoting their utilisation.

Social imbalances created by years of apartheid policies were addressed through “Namibianisation” of the fishing sector. This was largely implemented through manipulation of the fishing levies in favour of Namibians. Similarly, a job creation policy over the last 12 years has seen employment in the sector grow from around 5 000 Namibians to 14 000.

In 1990 Namibia was therefore, in an enviable situation in terms of fisheries management: the authorities were able to initiate a new management regime without the historical social and political constraints that so often inhibit policy changes.

Namibia is classified as a “developing” country, although the fisheries sector more closely resembles that of a modern developed nation. Catches have remained fairly constant between 500 000 and 600 000 tonnes per annum since Independence and the contribution of fisheries to the GDP has ranged between six and eight percent. Exports have however increased from about N$ 830 million[13] in 1992 to N$2 600 million in 2000 making fisheries the second most important sector of the Namibian economy, after mining.

1.1.3 South Africa

South Africa held its first democratic elections in 1994, marking a break from the previous white-dominated apartheid system. In general the new South African administration inherited robust fish stocks, with the pelagic stocks in particular recovering following an extended period of depletion.

As with Namibia, the previous administration had created considerable social imbalances. These are being addressed by adjusting the ownership/quota allocation in favour of local communities who previously had little chance of competing against the large multi-national fishing companies. This period of “transformation” (as it is known) has created instability in the industry with many new entrants and the reduction of rights to established companies (FAO 2001a).

Approximately 27 000 fishers are employed in the fishing industry catching between 500 000 and 700 000 tonnes per annum (the variation is largely determined by the abundance of the small pelagic resources). Most of this is used locally, although exports have increased in recent years, mainly hakes. Only a small proportion of the small pelagic landings are exported, mainly to the United Kingdom (200 tonnes, valued at US$ 300 000 in 2000, compared to 2 600 tonnes from Namibia, EU 2001). Per capita consumption is 6.4 kg/year. Fisheries contribute less than one percent towards GDP, although within some regions, especially the Western Cape, this figure is much higher.

1.2 Fish stocks and fisheries

The large-volume small pelagic fish stocks of the region can be grouped into three categories: the sardinellas Sardinella aurita and S. maderensis, sardine Sardinops sagax and anchovy Engraulis capensis and the horse mackerels Trachurus capensis and T. trecae. These resources all occur close to the coast, well within the EEZs of the three countries.

1.2.1 Sardinellas

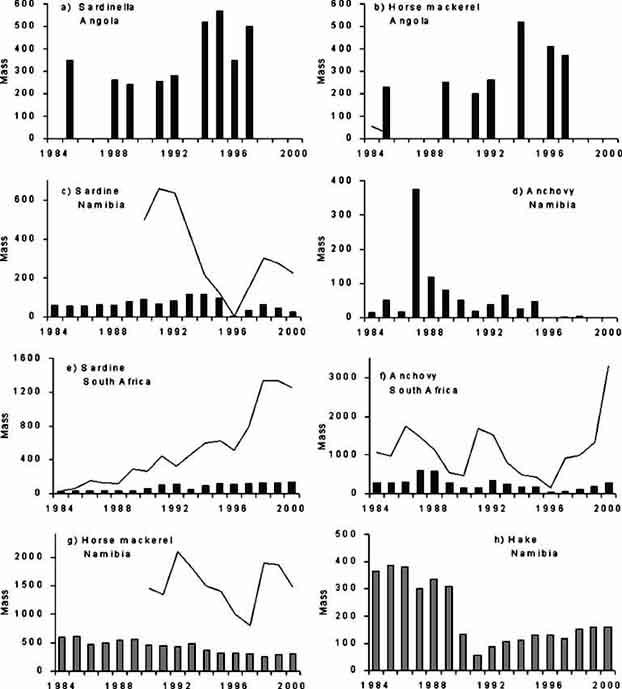

The two species of sardinella are, within the region under review, restricted to Angola, although these stocks are shared with countries to the north. In the past sardinella was utilized by the Soviet fleet for fishmeal, but it is increasingly being frozen for human consumption. The catch was about 50 000 tonnes in 1996, compared to between 60 000 and 100 000 tonnes between 1955 and 1973 (Hampton et al. 1998) (Fig. 2a).

1.2.2 Sardine and anchovy

The sardine and anchovy stocks of the southeast Atlantic are almost entirely restricted to Namibia and South Africa. Both species occur as northern and southern stocks, which, although genetically identical, are considered separate for management purposes as they are geographically widely separated and according to tagging and genetic studies mixing takes place at a very low rate. Although most of the northern stock of sardine (referred to as the northern Benguela stock) occurs in Namibian waters, its distribution extends into Angola, where it is found in the relatively cool waters just north of the Namibia/Angola border, making this a shared stock. Whereas the anchovy and sardine stocks of South Africa, which occur in the southern Benguela and Agulhas systems, are currently at record high levels (Figs. 2e & f), the northern Benguela stocks are severely depleted (Figs. 2c & d).

1.2.3 Horse mackerels

Trachurus trecae occurs in Angola while T. capensis occurs in all three countries. As with sardine and anchovy, the northern and southern Benguela stocks of T. capensis are widely separated and although genetically identical are considered separate stocks. Southern Angolan is the northern limit of the distribution of T. trachurus, but the biomass occurring in Angolan waters is small and therefore for management purposes this stock can be considered as “Namibian”. As with sardinella, T. trecae was exploited mainly for fishmeal in the past but is now increasingly frozen for human consumption, although in July 2002 the Russian fleet was granted a quota of 300 000 tonnes of small pelagic fish, which will be largely horse mackerel (Lankester 2002), and presumably this will be used for fishmeal. Also in common with sardinella, a small catch of perhaps 2 000 tonnes per annum is taken by artisanal fishers for local consumption. Figure 2b shows the total biomass and catch of this species during recent years. T. capensis is fished by two fleets in Namibian waters, with purse seiners harvesting the juveniles close to the coast and midwater trawlers catching the adult part of the stock further offshore in waters of 200 m and deeper. Catches of the two fleets averaged 68 000 tonnes and almost 300 000 tonnes per year respectively during the 1990s (Fig. 2g). In South Africa purse seine catches of juvenile T. capensis are severely restricted in an attempt to increase the midwater fishery that targets adults. The total catch of this species is considerably less than that of Namibia.

1.3 International agreements

The countries of the southeast Atlantic have signed most of the major international fisheries conventions, agreements and arrangements. In addition, several regional fisheries management and research instruments have also been signed in recent years (see also 2.4.4). Not all of these agreements have been ratified, for example South Africa has yet to ratify the UN Fish Stocks Agreement (UNFSA)[14] and the FAO Compliance Agreement[15]. Namibia is unusual in that soon after an international or regional instrument is signed the full text is published in the national Gazette, which means that the instrument becomes legally enforceable (see Sect. 37 of the Namibian Marine Resources Act, MFMR 2000). Thus, ratification occurs almost simultaneously to the country becoming a signatory.

The SADC Protocol on Fisheries has recently been adopted (signed August 2001). This Protocol incorporates international best practice for fisheries management and the key elements of various international instruments, thereby promoting sustainability of the fish stocks and ecosystems of the SADC region and the communities reliant on them. This Protocol has not yet come into force, but there are high expectations that it will have a positive effect on fisheries management in the region.

Another agreement that should improve cooperation between fishing nations of the southeast Atlantic is SEAFO[16]. This organization has been negotiated within the framework of the UNFSA to manage the high seas stocks of the southeast Atlantic. It will not have any direct bearing on the large-scale commercial small pelagic fisheries of the region, however, any mechanism that improves communication, transparency and, crucially, trust between nations sharing fish stocks is likely to have a positive impact on the management of shared resources.

Two further initiatives that have had a significant impact on the fisheries management of the region are the BENEFIT[17] and BCLME[18] Programmes. These two programmes are complimentary research activities that, apart from investigating many of the key biological complexities of the Benguela Current system, have served to bring together the scientists and managers of the region. Language barriers and cultural differences across the political spectrum have been reduced, enhancing communication between the fisheries scientists of the region, and also at the managerial and political levels.

Figure 2. Annual catch and biomass estimates (in thousands of tonnes) of the large volume small pelagic resources of the southeast Atlantic (bars = catches, lines = biomass). Namibian hake is also presented. Note that some species are not assessed, and not all data are available

2. IS FISHERY MANAGEMENT SUCCESSFULLY ACHIEVING THE FOUR COMPONENTS OF SUSTAINABILITY?

2.1 Bio-ecological component of sustainability

A general theme that is prevalent in virtually all of the main international instruments is that of protecting, conserving and restoring fishery resources, the environment, habitat, ecosystem and biodiversity.

All three countries have demonstrated recognition of the importance of conserving fisheries resources and restoring depleted or overfished stocks to higher levels through various official proclamations, many of which have been translated into policies and legal instruments.

The Angolan Constitution, which is much older than Namibia and South Africa’s, makes no direct reference to the sustainable utilisation of marine resources, but the recently formulated fisheries policy clearly promotes such practices.

The Namibian Constitution requires that natural living resources are sustainably used. The policies and legal framework for implementing fisheries management incorporate the main elements laid down in international instruments and these have gained widespread praise internationally (MFMR 2002a).

Similarly the South African Constitution also requires the protection and optimal utilisation of natural resources, and the Marine Living Resources Act (RSA 1998) provides specifically for the conservation of the marine ecosystem, the long-term sustainable utilisation of marine living resources and the protection and orderly access to exploitation of resources.

However, these countries have had mixed success at implementing these policies as illustrated in several of the examples below.

2.1.1 Prevention of overfishing

The southeast Atlantic has a history of excess capacity and overfishing. This has been considerably reduced in some sectors, while in others it is still problematic.

Angolan fisheries are managed by a mixture of licences and TACs. Unfortunately the systems used to ensure that TACs are adhered to are frequently insufficient and therefore these controls have limited effect (Hampton et al. 1999). Overfishing is therefore, believed to still occur in some sectors, although this seems not to be the situation in the small pelagic fishery (see 2.3.1).

In Namibia fishing is also limited primarily through output controls consisting of individual non-transferable quotas, although entry rights are also enforced. Catches must be landed at one of two fishing ports (transhipments at sea are not permitted) under the control of fisheries inspectors while an effective surveillance system of patrol vessels, aerial patrols and on-board observers ensures that all other legal requirements are met. Indeed Namibia has developed a reputation as having one of the more effective monitoring, control and surveillance (MCS) systems (Nichols submitted). Of the total landings 90 percent come from TAC controlled stocks and so the Namibian authorities have been able to control the fishing pressure on these stocks and as outlined in the next section this has yielded very positive results in some sectors. The South African system of management is very similar to the Namibian system, but lack of compliance and control, particularly in the near-shore fisheries is an on-going problem (see 2.4.3). Of note is the fact that the South African pelagic fishery is the longest standing quota-managed fishery in the world

While excess capacity (and consequently over-fishing) is a burning issue for many of the fishing sectors in South Africa, large increases in the biomass of the sardine and anchovy stocks during the past decade, and hence TACs, have resulted in a short-fall of catching capacity and the industry has been unable to utilise the full TAC (see also 2.4.4). In contrast, the small pelagic purse seine fleet in Namibia has declined from 35-45 vessels in the 1980s and early 1990s to less than 15 vessels by the millennium in response to declining TACs. Even so, these vessels are normally active for just a few months of the year, catching less than 10 tonnes per GRT each year. This compares to about 90 tonnes per GRT per year in the mid-1970s, suggesting that a large over-capacity still exists (Manning 2000). Similarly, most of the Namibian canning and fishmeal plants lie idle for the greater part of each year.

Some resources, however, are unmanaged and consequently tend to be overfished. For example, Namibian anchovy was once of major importance, but since the late 1980s there have been no output controls. Catches have declined to less than 2 000 tonnes per annum for much of the past decade (Fig. 2d) compared to over 200 000 tonnes in the 1970s (Boyer and Hampton 2001), although the relative importance of environmental impacts and fishing in this decline is not clear. It is of interest, however, that in comparison the South African anchovy stock, which is carefully managed, is currently at record levels (Fig. 2f).

2.1.2 Protect, conserve and restore fisheries resources

The authorities in all three countries have tended to follow the scientific recommendations on TACs to a degree rarely seen elsewhere. In the case of Namibia and South Africa there are demonstrable recoveries of some previously depressed fish stocks, illustrating that these countries have successfully reduced overfishing and these resources are recovering towards their previous levels.

Historically both the South African and Namibian sardine and anchovy stocks have shown typical responses to fishing. The sardine stocks in both countries were heavily fished in the 1960s and suffered spectacular crashes. Anchovy replaced sardine in the southern Benguela, while a mixture of anchovy, juvenile horse mackerel and reduced catches of sardine sustained the industry in Namibia. Under a cautious management strategy the South African sardine stock has gradually recovered to the extent that by 2002 the resource was probably as large as it has ever been since fishing started (Fig. 2e). Anchovy, being a short-lived species, has shown more variability, but has also yielded very large catches during the past decade (Fig. 2f). In contrast, as noted below, the biomass of both species has been at an all-time low in Namibia for much of the past decade (Figs. 2c & d).

While not a pelagic stock, the well-documented example of the recovery of the Namibian hake stocks Merluccius capensis and M. paradoxus during the 1990s is another example of stringent management eventually bearing fruit (Fig. 2h). At Independence in 1990, the Namibian authorities inherited an over-fished hake stock. Fishing licences for foreign vessels were denied and a TAC of just 60 000 tonnes was granted to local operators, more than a six-fold reduction compared to the annual catches of the previous decade. As the various biomass indices indicated that the stock was recovering the TAC was gradually increased and in the 2000/1 fishing year it was 195 000 tonnes

However, not all management strategies have worked. For example ten years after Namibian Independence the biomass of the northern Benguela sardine stock was as low as it had ever been since fishing began. After encouraging signs of a recovery soon after Independence, adverse environmental conditions during the middle of the 1990s, combined with overfishing resulting from an unwillingness on the part of the authorities and the industry to take heed of the warning signs of poor recruitment and a falling biomass, reversed the gains made. By the end of the 1995 fishing season the stock had fallen to a few tens of thousands of tonnes, but when these fish migrated into southern Angola, Namibian purse seiners obtained licences to harvest them and the population was virtually fished out (Boyer et al. 2001). Since then, due to its importance to the economy and the number of workers employed by this industry, relatively small TACs were granted in the hope that they were sufficient to maintain the industry, while at the same time small enough to allow a recovery in the stock. When in 2002 it became clear that this policy was not working and the stock had fallen to extremely low levels, all sardine-directed fishing in Namibian waters was stopped.

Except for what was probably a crucial period in the mid-1990s, adult fishing mortality rates were broadly similar for both the northern and southern Benguela stocks during the 1980s and early 1990s while the juvenile fishing mortality rate was considerably less in the north (see below), yet the biomass of the South African stock is currently at a record high level. It is quite possible that a regime shift[19] has occurred, or the stock size is so low that dispersal[20] is occurring, and therefore the Namibian stocks may never recover. It is tempting however to speculate on what the current biomass could be if the stock had received adequate protection during the period of adverse environmental conditions. This experience also underlines the importance of a management agreement between Namibia and Angola for this stock.

2.1.3 Limiting by-catch

Excessive by-catch is recognised as a contributory factor to unsustainability, and the need for its control is noted in a number of international instruments.

Namibia has developed a unique system to minimise by-catch whereby no edible or marketable fish taken as by-catch may be discarded, which is monitored by ship-board observers, and levies must be paid on the by-catch (see Table 1, 2.3.2). The levies are high enough to discourage targeting on such species, but not so high as to encourage discarding. Evidence that this system works comes from the hake fishery. Monk has traditionally been a valuable by-catch and constituted around three percent of the total hake fishery landings. When the by-catch levy was introduced by-catch of monk declined immediately to less than two percent as a result of reduced targeting of this species.

Further by-catch limitations are imposed in the midwater trawl fishery. If catches of hake or young horse mackerel exceed five percent the fleet must leave that area. Similarly, if the purse seine fleet catches more than five percent juvenile sardine, the area is closed to fishing for several weeks. However, it has to be noted that rumours of discarding of young sardine constantly circulate in the fishery, indicating that control of juvenile sardine fishing mortality may not be entirely successful.

South Africa has developed an unusual method of limiting by-catch of young fish in their purse seine fishery. This fishery is complicated by the fact that the two main target species, sardine and anchovy, cannot both be optimally utilized, as there is a significant by-catch of juvenile sardine in the anchovy directed catches. About 80 percent of the anchovy catch is juveniles, and the juveniles of these two species shoal together. Thus the higher the anchovy directed catches, the greater the by-catch of juvenile sardine, which may negatively affect the future adult sardine directed fishery. In order to control this by-catch, and to obtain the best possible anchovy catch without putting the sardine fishery at risk, anchovy TACs and sardine by-catch limits are set three times during the year, according to a pre-defined management procedure. In essence the allowable catch of anchovy is adjusted according to the species mix and the catch of juvenile sardine, which itself is dependent on the total sardine stock size and the number of recruits (De Oliveira 2001).

Angola, Namibia and South Africa also use a variety of technical measures in the trawl fisheries to allow escapement of small unwanted fish, but Namibia has also recently made compulsory the use of fixed selection grids in the hake trawl fishery. While this is primarily to allow pre-recruits of the same species to escape, it will also enable smaller unwanted by-catch species to also escape.

2.1.4 Ecosystem management

Ecosystem approaches to management are currently being investigated in South Africa and Namibia (through a BENEFIT/FAO/Government of Japan Cooperative Programme GCP/INT/643/JPN, FAO 2001b), and indeed a stated goal for Namibia’s fisheries is to establish a fully functional ecosystem health monitoring system by 2005 (MFMR 2002a). Both the Marine Resources Act, 2000 (Namibia) and the Marine Living Resources Act of 1998 (South Africa) include legislation prohibiting destructive fishing practices such as the use of driftnets and fishing methods using explosives, poisons and other noxious substances.

However, issues of more general environmental health (including ecosystem and biodiversity issues) are much less well recognised than those of sustainable utilisation and receive less support from the region’s fisheries authorities. Small pelagic stocks are often considered key species exerting a wasp-waist control on the ecosystem (Cury et al. 2000), therefore, the responsible management of this species is of critical importance to the functioning of the ecosystem.

For example, during the period that the sardine and anchovy stocks have been in a depressed state in Namibia, no allowance has been made for endemic seabirds that rely on these stocks for food when setting catch levels. This is despite a decline in the populations of these seabirds to such low levels that they are classified as threatened or endangered, largely as a result of the reduction in available prey (Crawford et al. 2001). However, the Namibian authorities are currently drawing up National Plans of Action for several vulnerable groups, especially seabirds and sharks, and these are expected to incorporate ecosystem considerations.

It is worth noting that at the 2001 Reykjavik Conference on Responsible Fishing in the Marine Ecosystem the Namibian Minister of Fisheries and Marine Resources (Dr A. Iyambo) was elected Chairman of the Drafting Committee fort the conference declaration (Reykjavik Declaration on Responsible Fishing in the Marine Ecosystem), indicting that such issues are understood at the highest level in Namibia. In addition, one of the main goals of BCLME is to implement ecosystem management (see Section 2.4.4) and therefore, some progress is expected in this field in the near future.

2.1.5 Multispecies management

Productive upwelling systems such as the Benguela are typified by large stocks of few species that lend themselves to single species management more readily that more complex marine systems. It is therefore not surprising that all three countries issue single species rights, although there are some examples of multispecies management measures, for example the sardine and anchovy fishery in South Africa described above. Indeed this fishery is a classical example of successful multispecies management where the development of an operational management procedure (OMP) has seen catches maximised and stabilised, while also enabling the industry to select the proportions of the two species that they harvest (De Oliviera 2001).

There are, however, multispecies fisheries that harvest several species, yet the catch of only one species is controlled. For example, rights for tunas and swordfish (Xiphias gladius) in Namibia have recently been extended to include all “large pelagics”. While catches of these species are controlled through a TAC (the level of which is determined by ICCAT), other “large pelagics” such as sharks are now being targeted by many operators. Indeed, several thousand tonnes are now caught annually. Unless controlled this figure is expected to increase putting the sustainability of several shark species at risk. Similarly, when a right of exploitation for small pelagic fish is given in Namibia, limited quotas for sardine and juvenile horse mackerel are issued, but there are no limitations regarding other small pelagic species. This means that any right holder may catch unlimited amounts of anchovy, round herring (Etrumeus whitheadi), chub mackerel (Scomber japonicus), and, although rarely targeted, pelagic goby (Sufflogobius bibarbatus).

2.2 Social component of sustainability

Social aspects of fisheries management do not feature highly in the main international instruments. Several have been identified in the analytical framework and are reviewed below, but an additional aspect, equity, was felt to be of importance (see also Cunningham and Maguire 2002) and therefore this is also discussed here.

2.2.1 Optimal utilisation of resources

The catches from small pelagic fisheries are fully utilised with little waste, however, much is processed into low value products. In common with many large volume small pelagic fisheries around the world much of the produce from Namibia and South Africa is in the form of fishmeal or oil for the animal feeds and chemical industries. Compared to other sectors of the fishing industry a relatively small amount of the pelagic catch is utilised for human consumption. In Namibia and South Africa most of the sardine catch is canned, although as the TAC has expanded in South Africa in recent years a far greater proportion has gone into industrial products. The product is aimed at the lower end of the economic market. The entire anchovy, round herring and juvenile horse mackerel catch is utilised for fishmeal and oil production. In Angola where per capita consumption of fish is higher, a much greater percentage of all species is utilised for human consumption

The midwater trawl catch is either converted to fishmeal or utilised for low-value products including frozen whole round fish and dried fish, which are sold cheaply within southern Africa. Fish consumption in Namibia has traditionally been low, at around 4 kg/capita/year at Independence, one of the lowest of all fish producing nations. In an attempt to change this, the private sector and government, with donor assistance from Japan (through the Overseas Fisheries Co-operation Foundation) have combined to make fish more readily available throughout the country and publicised the benefits of eating fish. This has resulted in more than doubling of the per capita consumption rate by 2002 (MFMR 2002a). According to Clark (1997), in recent years this has produced a major change across southern Africa, improving food security and forcing down the price of beef.

Despite this the Namibian horse mackerel TAC is consistently under-utilised, all anchovy for human consumption is imported from the Mediterranean, while sardine products have remained virtually unchanged for several decades even though higher-priced quality herring products are imported from Europe. These facts all suggest that product diversification may well yield real benefits for the pelagic sector.

It is perhaps interesting to note that Namibia requires that 60 percent of the hake catch is landed as fresh fish for processing onshore. This policy has resulted in the establishment of 20 processing factories in the past decade, creating more than 5 000 jobs (MFMR 2002a).

2.2.2 Safe, healthy and fair working environments

Of the social issues that do emerge in the main international instruments, one is that workers, both on land and at sea, should be afforded safe, healthy and fair working conditions. This is particularly relevant to developing countries where working conditions of the lower paid (including factory workers and fishers) have frequently left much to be desired. Namibia is a member of the International Labour Organization (ILO) and has ratified a number of its conventions. In 1992 Namibia passed a Labour Act, which meets some of the provisions of the ILO, giving workers greatly improved levels of social protection. All three countries of the southeast Atlantic are members of the International Maritime Organization (Angola joined in 1977, Namibia in 1994 and South Africa in 1995) and are signatories to the SOLAS[21] Convention, which requires certain shipboard safety standards to be met and all sea-going workers to have basic safety-at-sea training. Compliance is however believed to be low and a number of accidents during the past couple of years, particularly in Namibia, involving fishing vessels, and deaths resulting from these accidents have alarmed the government and unions alike and further regulations are likely.

AIDS/HIV[22] is of major concern in southern Africa. The current infection rates of more that 20 percent in Namibia and South Africa are predicted to increase and the social and economic consequences are expected to be massive over the coming decades. While this disease, and other large-scale social disruptions such as drought, war and political upheaval, is difficult to plan for, both Namibia and South Africa have implemented policies to limit and reduce HIV infection rates and to mitigate against the social disruption caused by AIDS and AIDS-related deaths.

2.2.3 Aquaculture as alternative

The Code of Conduct for Responsible Fishing (CCRF, FAO 1995) proposes that states should consider aquaculture as an alternative source of fish. This is particularly topical in Namibia where, with the decline of several of Namibia’s pelagic stocks, and the general desire to increase fish productivity, the authorities have recently introduced an aquaculture policy to stimulate and encourage developments in this sector (MFMR 2002b). Several oyster and mussel farms already exist, but a large expansion of this previously neglected sector is being planned. Namibia’s uninhabited coastline, highly productive unpolluted waters, and availability of fishmeal, is seen as being highly conducive to aquaculture. Whether a large-scale industry will develop remains to be seen.

Mariculture is also increasing in South Africa where 4 000 tonnes a year is produced, much of this attributable to abalone and mussel production. For the first time, in 2002 abalone farms were expected to produce more than from wild stocks. Development of other mariculture species is also attracting interest, including the farming of salmon in offshore cages.

2.2.4 Assist developing countries

Several of the international instruments state that developed countries are obliged to assist the less developed to implement their fisheries management systems in accordance with the accepted principles of sustainable utilisation. This is of course particularly relevant to the states of the southeast Atlantic where Angola is classified as one of the “least-developed” countries, and Namibia and South Africa as “developing”.

Indeed all three countries have received considerable assistance through the FAO and other international organizations as well as nations such as Norway, United Kingdom, Iceland, Germany, Portugal, Sweden, Japan, Spain and others. In Namibia this has been equivalent to approximately one third of the total fisheries management costs (Wiium and Uulenga 2002), although a large proportion has been for human and capital project development and therefore, this assistance is declining as the state institutions mature.

In recent years it has been recognised by politicians and managers in Africa that the continent cannot continue indefinitely to expect aid from the developed countries and that regional cooperation needs to be developed. Out of this concept grew NEPAD (see 2.4.4), which aims to create sustainable growth and development such that the African nations will become equal partners in global trade and assistance will no longer be needed.

Even prior to the concept of NEPAD the three countries of the southeast Atlantic have provided considerable assistance to each other through BENEFIT and BCLME (see 2.4.4). While both of these programmes are largely driven by external funding, much of the research has been of a cooperative nature within the region. Indeed BENEFIT has already had a very positive impact through training and has enabled Angolan scientists to become more involved in fisheries science (SADC 2002).

Various other bilateral arrangements have also been developed, such as assistance from South Africa to Namibia in technically advanced fields of research (stock assessment and acoustics), while Namibia has also reached a Technical Cooperation between Developing Countries agreement with Mozambique, offering preferential treatment for horse mackerel exports to that country in order to improve the food security of the region.

2.2.5 Equity

One aspect that is seen as crucial to the success of fisheries management in southern Africa is equity. This is particularly relevant in Namibia and South Africa where decades of apartheid has resulted in large sections of the population being denied access to all but the most menial of jobs in industries like fisheries. Similarly, the profits from fisheries have accrued largely to white-owned (often multi-national or foreign) companies with little benefit to local communities.

Disparate educational and work opportunities, and subsequently incomes, are seen as one of the biggest threats to national security and prosperity and hence in recent years considerable effort has been put into redressing the imbalances of the past. The actions that have been taken within the fisheries sector are described below.

2.2.6 Namibianisation

At Independence the newly established government inherited a fishing industry that was largely owned and managed by foreigners, using foreign registered vessels and foreign crew. Most products were either exported in their raw form, or processed at sea. Apart from being a poor country, Namibia also had an unemployment rate of approximately 40 percent. Clearly Namibians needed to not only take control of their own national assets, but also to benefit from them, both in terms of income and employment. To this end a policy of Namibianisation was introduced to the fisheries management system; a system designed to redress the injustices of the past and to ensure equity between all racial groups within the country.

In essence this system was designed to advantage Namibians through rights and quotas, which are allocated preferentially to applicants who inter alia:

are Namibian, or if a company, 90 percent Namibian-owned,

have vessels owned by Namibians and

work towards the advancement of previously disadvantaged persons.

In addition, substantial economic incentives are also in place to further encourage rights holders to increase the involvement of Namibians in fisheries. Quota levies are charged for all managed species. These are paid in advance and are charged per tonne of quota allocated to the right-holder. As an example in the hake fishery the quota levies per tonne are as follows.

|

Basic levy |

N$880 |

|

Vessel Namibian flagged |

N$660 |

|

80% Namibian crew |

N$440 |

|

Fish processed on shore |

N$220 |

As a result of these policies, of the 171 rights holders all except one are currently majority Namibian-owned. The proportion of horse mackerel quota in Namibian hands has risen from 14 percent at Independence to around 80 percent in 2002 while the other small pelagic quotas are entirely in Namibian hands. The proportion of Namibian vessels has increased from 50 percent in 1991 to around 80 percent and Namibian crew on fishing vessels has increased from 42 percent to 65 percent between 1994 and 2000, with most sectors being over 80 percent (MFMR 2002a).

In the early years after Independence a small proportion of the TAC of each species was set aside for newcomers in a further effort to increase local involvement in the industry. This had limited success due to many of the newcomers leasing their quotas for immediate gain. Therefore, a new policy has recently been implemented whereby established rights holders are required to enter into partnerships with newcomers. Approximately half of the companies involved in fisheries are now “newcomers” while restructuring of many of the established companies has further increased the degree of Namibian participation in the industry.

In practice however, while quotas are not officially transferable, the established companies have often entered into unequal partnerships with newcomers to obtain access to extra quota, resulting in limited direct participation in the industry by newcomers (see below) and concerns about the true level of Namibian control of fishing quotas (Manning 2000).

2.2.7 South African transformation

When the new democratically elected government of South Africa assumed control of the marine resources in 1994, there was a clear need to promote equity in the fishing industry, in line with the “transformation” process that was taking place in all spheres of society. The aim of the authorities was to build a fishing industry that broadly reflected the demographics of South Africa in its ownership and management (Government Gazette No. 22517, 2001). Since 1996 the government tried to implement this policy by allocating fishing rights to “historically disadvantaged individuals” (HDIs), without unduly penalising established companies that were important providers of employment and economic activity in coastal areas. This was problematic as the major commercial fisheries were already fully utilized and thus rights that were allocated to black-owned small, medium and micro-enterprises (SMMEs) often were so small that they were not economically viable (Moosa 2002).

A new system was implemented in July 2001, whereby applications for medium-term rights of four years were be allocated. By this time most established companies had restructured ownership towards meeting criteria relating to transformation and many had a significant black shareholding, and this was recognised in the rights allocation process. The applications were assessed by a fishery-independent advisory committee, and scored according to various criteria, including the degree of transformation, involvement in the fishery, capacity to harvest and process the resource, creation of employment, past performance and the degree of “paper quota” risk.

As with Namibia, the beneficial ownership of many companies is difficult to ascertain, but at least on paper this process has been fairly successful. For example, just twenty years ago the South African hake trawl TAC was shared between six white-owned companies, while now 73 percent of the rights are majority-owned by HDIs. The pelagic sector is over 75 percent majority HDI-owned (DEAT 2002a).

2.3 Economic component of sustainability

The major international fisheries management instruments have been summarised into three main economic components in the analytical framework. These are briefly reviewed below.

2.3.1 Balancing fishing capacity with resource yield

The objective of balancing fishing capacity with the yield of fish stocks is clearly stated in many of the international instruments.

At Independence one of the first actions taken by the Namibian government was the exclusion of more than 100 foreign fishing vessels from the EEZ (Nichols submitted), considerably reducing the fishing pressure on the ground fish stocks. Since then the Namibian management system has been one of output controls rather than input and therefore capacity is only loosely controlled. In new experimental fisheries however, a precautionary approach is applied to capacity build-up.

In an effort to reduce capacity, and maximise local involvement in the fishing industry, South Africa has recently terminated a long-standing agreement for Taiwanese vessels to fish tuna in South African waters, while Japanese vessels have been reduced from eighty-two to sixty-nine. The authorities have also recently refused to allow European Union (EU) vessels to fish in their waters (DEAT 2002a).

While excess capacity has been identified as one of the major (if not the main) causes of unsustainability, the Law of the Sea (Art. 62, Para 2, 1982) requires that states should make any excess yield available if the nation does not have the capacity to utilise it. For developing states this is somewhat problematical as in some cases fleets are being built up slowly in an attempt to match effort with yield, rather than to overshoot this critical balance. Given that the yield of fish stocks is highly variable and the assessment of fish stocks imprecise, it is often difficult to determine with any certainty whether a stock is genuinely under-fished. A case in point is the Namibian horse mackerel resource. During the past decade the catch has routinely been 15 percent (65 000 tonnes per annum) below the TAC, promoting fears within the government that foreign fleets may lay claim to the unutilised yield.

However, some attempts have been made within the region to match regional capacity with available resources. In 2002 South Africa’s sardine and anchovy TACs were increased by 80 percent to record high levels, above the capacity of the local purse seine fleet. Conversely, Namibia’s sardine and anchovy stocks are at historically low levels. The Namibian purse seine fleet has contracted drastically in recent years: in 1999 there were still around 40 vessels in operation, whereas this had decreased to around 13 by 2002, but even these vessels are severely under-utilised while the canning factories (and crucially factory workers stand idle). An agreement was reached whereby Namibian purse seiners, under-utilised due to the zero TAC for Namibian sardine, could apply for licenses to assist South African companies to land their quotas. This was seen as “an example of how the New Partnership for Africa's Development promotes innovative partnerships for the development of the African continent and forms the basis for a sustainable development programme for Africa" (South Africa's Minister of Environmental Affairs and Tourism, Mohammed Valli Moosa). Similarly, about 50 South African fishing vessels are licensed to fish in Namibian waters, primarily in the large pelagic fishery.

In Angola the state of the small pelagic stocks is less clear, but a recent workshop on the small pelagic fish of Angola, Congo and Gabon concluded that Angola’s sardinella stocks are underexploited while the horse mackerel T. trecae stock is probably harvested at around MSY. The catch of small pelagics decreased sharply with the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1992, although it has recently started to increase again. Although the national “commercial” fleet consists of about 200 vessels, including ten purse seiners, many are not in working order as a consequence of the war, resulting in a lack of local capacity to harvest the small pelagic resources.

There are currently about ten Namibian-flagged purse seiners with licences to catch small pelagics in Angolan waters. This was initiated in 1995 when an unusually large part of the Namibian-Angolan shared sardine stock was located in Angolan waters and the Namibian purse seine fleet obtained licences to continue catching sardine in Angolan waters once the Namibian TAC was filled. This bilateral agreement included Angolan vessels being given access to Namibian hake quota. Since the collapse of the sardine resource, these vessels have remained in Angola fishing on the apparently under-utilised sardinella and horse mackerel for a Namibian-funded fishmeal plant.

However, most of the under-capacity in Angola is taken up by distant-water fleets. In July 2002 it was announced that the Russian fleet is allowed to catch 300 000 tonnes of mostly small pelagic fish like horse mackerel. In addition the fisheries agreement between Angola and the EU, first signed in 1987, was updated in August 2002 and will continue until 2004. This agreement allows 22 shrimp vessels, 15 tuna seiners, eighteen surface longliners, an unspecified number of demersal vessels up to 4 200 GRT, and two small pelagic trawlers, to fish in Angolan waters. Apart from shrimp, there are no catch limits, and the effort limits can be increased if both parties agree and contributions are made towards the improvement of Angola’s fishing industry. In return 35 percent of the U$15.3 million agreement is earmarked for projects that benefit the local fishing industry, and other benefits include training, institutional support in regional fisheries organizations, MCS and aquaculture. Whether this agreement conforms to the Law of the Sea (Art. 62, Para 4, 1982) is unclear, but it has been strongly criticised by conservation groups for its non-sustainability, lack of catch limits and the fact that effort limitations are not based on scientific advice. There are also concerns that Angola does not have the infrastructure to ensure that area limitations are observed, putting the local artisanal fishery at risk (Lankester 2002).

2.3.2 Trade must be conducted according to WTO rules

Many of the international instruments call on states to conduct trade without artificial subsidies or restrictive barriers. In contrast to many fishing states both the South African and Namibian fisheries operate without subsidies. Financial support is offered in the form of fuel tax rebates for certain sectors of the industry, e.g. the Namibian horse mackerel fleet, to enable them to compete with foreign-registered vessels that obtain fuel tax-free, while the South African fishing industry does not pay the “road levy” normally charged on fuel in that country. Also, although not a direct subsidy, South Africa has over the years put various structures in place to assist with the acquisition of capital for investment in the fisheries sector.

Many countries have developed heavily subsidised fisheries, which as noted at the previous workshop has exacerbated over-capitalisation and hence over-fishing. Namibia has, since Independence, taken the view that the marine resources should be harvested to the benefit of all Namibians, and therefore fishers are required to pay a quota levy for the right to harvest these resources. These levies have broadly been calculated as being about 15 percent of the landed value of the fish. In 1994 this percentage was realised, although by 1999 it had decreased to about seven percent (Table 2), largely as companies were charged the reduced levies for becoming more “Namibianised” (see 2.2.4). Even after the cost of fisheries management has been deducted Namibia has a positive resource rent[23], calculated at about three percent of the landed value of the fish in 1999. This is believed to be one of the highest resource rents in the world (Wiium and Uulenga 2002). However, as MCS costs are expected to increase in the future with the imminent acquisition of a third patrol vessel, it is possible that resource rents may soon become negative.

Table 1. Total government receipts from the Namibian fishing industry (N$ ‘000s)

|

|

1994 |

1995 |

1996[24] |

1997 |

1998 |

1999 |

|

Quota fees |

108 000 |

90 600 |

45 500 |

72 200 |

75 200 |

91 000 |

|

By-catch fees |

9 600 |

8 000 |

14 800 |

5 000 |

6 200 |

9 000 |

|

Research & training |

8 600 |

7 200 |

6 100 |

8 300 |

9 900 |

13 300 |

|

Licence fees |

30 |

162 |

162 |

158 |

160 |

172 |

|

Total |

131 830 |

111 093 |

72 000 |

91 029 |

97 259 |

119 598 |

One of the penalties of a resource rental system is that the incentive to cheat becomes much larger, which requires good control. In addition to Namibia’s effective MCS system, it is believed that legal rights holders have become more protective of their resource since these levies were introduced and the level of self-regulation has increased as illegal competitors are soon reported to the authorities.

Poor nations are often perceived as unequal partners in international trade as the examples in 2.3.1 illustrate. However, exchange rates tend to appreciate in rich developed countries relative to developing countries, and, if resources are well-managed, can result in the balance of trade being to the benefit of developing countries. This has certainly been the case in Namibia and South Africa where the local currency has devalued approximately four-fold in the past ten years. This creates an even greater incentive to export products, and brings more foreign exchange for the country. However, this also increases the pressure on local authorities to raise quotas, resulting in increased likelihood of unsustainability, and reduced food security as the fish products become too expensive for the local market.

A further issue concerned with trade of fish that affects developing countries is transfer pricing of products by vertically integrated foreign-owned companies. This is believed to result in a significant loss of revenue for Namibia, especially with respect to hake caught by companies exporting to Spain (Manning 2000).

2.3.3 Prevention of trade in IUU fish[25]

The FAO International Plan of Action on IUU fishing calls on nations to prevent trade in fish from IUU vessels, and as a ratified signatory Namibia has enacted the necessary laws to prevent such activities. Namibia and South Africa have also supported the ICCAT resolution to draw up a black list of vessels flouting ICCAT control, while SEAFO and the SADC Protocol on Fisheries also provide further tools to prevent IUU vessels operating within the southeast Atlantic.

In the past vessels that have been involved in IUU fishing for toothfish and other deepwater species on the high seas (especially the CCAMLR region) have occasionally visited Namibian ports, and a Namibian registered vessel was reportedly engaged in IUU fishing during 2001. The Namibian authority has taken a serious view on such illegal fishing activities and has taken steps to ensure that any vessel engaged in IUU fishing will be apprehended and suitably penalised. Indeed Namibia is in the unusual position in that recently promulgated fisheries legislation gives the authorities control over Namibian flagged vessels operating outside of national waters and also effectively prevents IUU vessels from landing their catch in Namibian ports.

South Africa is estimated to have lost over N$ 3 billion in revenue since 1996 as a result of IUU fishing of toothfish in its EEZ waters around its Southern Oceans islands (GPF 2002). Therefore, all foreign-flagged fishing vessels landing in South Africa ports are required to have “gear” and “prohibited deepwater species” permits. Further, South African-flagged vessels fishing in international waters require a “high seas” permit (FAO 2001c).

2.4 Institutional component of sustainability

The analytical framework divides the institutional components of the international instruments into six broad themes, of which the first five are of particular relevance to overfishing in large-volume small pelagic fisheries.

2.4.1 Fisheries management should use the best available scientific evidence

The requirement that fisheries management should use the best available scientific information, including socio-economic and traditional knowledge, is clearly stated in virtually all of the international instruments. Recognising the importance of reliable and accurate scientific data, Namibia and South Africa have developed or re-structured their fisheries research institutes during the past decade or so to meet the demands of modern fisheries management. Angolan fisheries research on the other hand has been hampered by poor wages and lack of facilities (including a research vessel) and has had to place greater reliance on foreign assistance for direct information on the state of fish stocks (SADC 2002, Hampton et al. 1999).

While the governments of the southeast Atlantic region tend to follow scientific recommendations to a large extent, these TAC recommendations focus on the biological status of the stocks, while socio-economic aspects tend to be neglected. Both countries manage their fisheries through top-down state control systems and until recently stakeholders have not been included (at least formally) in the management process. In recent years, however, the industry and other stakeholders have been partly incorporated into the management system. In contrast, in Angola there is little communication between the Ministry and private sector (SADC 2002).

For example the Namibian authorities have attempted to incorporate some sectors of the fishing industry into the management process in a formal manner, based on the rationale that they can contribute to the process, and to ensure that the industry has a part-ownership of any decisions taken. The main mechanism for this has been through the establishment of working groups that have been formally mandated to participate in the analysis of biological data for most fisheries. The authorities have limited the concept of co-management to a rather narrow range of stakeholders, i.e. the managers of the fishing companies and, occasionally, employees. Fishers, factory workers, financial institutes, unions, other (competing) fisheries, conservation bodies, etc. are either not formally consulted, or are only included very late in the process. South Africa has taken this concept somewhat further, in that working groups are also mandated to develop structured management procedures (see below).

Fishing associations have been formed to represent each of the major sectors of the fishing industry in Namibia. While these associations have often acted as the de facto negotiators with the government, they have not been given any formal role in the fisheries management system. In recent years ad hoc meetings have also been held between the Namibian Ministry and the industry prior to the implementation of management decisions that may have far-reaching consequences to the stakeholders. These have taken the form of periodical consultative meetings, where some proposed management action is explained to the industry, but with limited opportunity for input (Olsen submitted).

South Africa has recently embraced co-management as part of their new fisheries management policy (Hauck and Sowman 2001), however, this is more to ensure equitable distribution of South Africa’s marine resources, rather than to improve the sustainability of the resources. In fact, it must be noted that as is often the case, the South African attempts at introducing co-management into their management system is primarily for small-scale fisheries.

South Africa is in the process of developing long-term management plans, which include operational management procedures (OMPs) for all of the major resources. These plans are being developed through consultation with all stakeholders and include MCS provisions as well as the socio-economic implications of different quota levels (FAO 2001a). An OMP has been used in the pelagic sector since 1991. This consists of setting the TAC according to harvesting rules that give an appropriate catch versus risk trade off. Uncertainty is included by requiring rules that provide robust performance over a range of plausible scenarios for resource status and dynamics (De Oliviera 2001).

The cost effectiveness of any management system is a fairly subjective judgement. The cost of the Namibian management system has been around 6 percent of the landed value of the fishery for most years since Independence, although as TACs and fish product value has increased in recent years this had declined to 3.6 percent in 1999. Alternative management systems have not been evaluated, although given the relatively short time that the current system has been in place, and its apparent success, this is not surprising.

The pressure for companies to become “Namibianised” and the restriction on quota transfers or sales, has resulted in complex company structures such that the true beneficial ownership is unclear, often being large companies (foreign-owned) when on paper Namibians are the beneficiaries. This allows the companies to reduce their quota levies as they can claim that the quota is being fished by Namibian majority-owned companies. Manning (2000) suggests that an ITQ system will firstly legitimise this system of “trading” in quotas, but also greatly simplify determining the real power behind quotas, thus enabling the appropriate resource rent to be extracted.

2.4.2 Precautionary approach

The precautionary approach has become prevalent in virtually all of the recently formulated international instruments. The management authorities of the region have all stated the intention of implementing precautionary strategies, but to date this has not been done in any formal way. The precautionary approach has been incorporated into the SEAFO Convention, although how it will be implemented is not described.

The precautionary approach is therefore applied in an ad hoc manner with some decisions being precautionary while others are not. Within the Namibia system there seem to be no clear examples of the precautionary approach being applied to the small pelagic fisheries, and consequently the stock has declined to such low levels that it may take many years, or even decades, to recover.

One aspect that is clearly stated in CCRF (7.3.3) is that management plans are an integral part of the precautionary approach. Namibia has developed a management plan for orange roughy, and OMPs for hake and seals, while NPOAs are being drafted for seabirds and sharks. As described in 2.4.1, the South African authorities have introduced OMPs for the sardine and anchovy fishery, as well as the hake and rock lobster fisheries, and are in the process of developing full management plans. Similarly, reference points are another element of the precautionary approach (e.g. see CCRF 7.5.3). While some reference points have been proposed for a number of species, none have yet been formally recognised in Namibia.

2.4.3 MCS[26] in the EEZ and on the high seas

The call for states and RFMOs[27] to establish effective monitoring, surveillance and control systems is repeatedly stated in the various instruments. Angola, Namibia and South Africa have had rather variable success at implementing effective MCS. Namibia was perhaps even more aware of the necessity for effective control of fishing activities as the newly-elected government inherited fish stocks that had been systematically depleted. It is estimated that of the 8.6 million tonnes of hake caught in Namibian waters prior to Independence, only 0.004 percent of the value found its way into Namibia (Nichols submitted). The third act passed after Independence was the proclamation of the 200 nm EEZ, indicating the importance attached by the government to responsible management of the marine region. This was followed in 1992 by the Sea Fisheries Act that was drafted for this newly established coastal state to take full control over its own resources and build up Namibian involvement in the industry. Subsequently Namibia signed various international fisheries management instruments that placed new obligations on the government that were not covered in the 1992 Act. Thus in 2000 a revised act succeeded the original one, incorporating the key elements of these instruments.

Concurrent with the development of the legislature to manage fisheries responsibly, Namibia’s MCS system was developed. This is based on having observers on all but the smallest fishing vessels to monitor compliance and collect vital research data, sea patrols to enforce compliance and air patrols to detect unlicensed vessels. Transhipments at sea are not permitted and all landings are monitored at the two commercial fishing ports, while discarding of by-catch is not permitted (see 2.1.3). A vessel monitoring system (VMS) is currently undergoing field tests and will be implemented during 2003.

Illegal fishing within Namibia’s EEZ is believed to have been virtually eliminated as only one incident has been recorded since 1995 (MFMR 2002a). Despite the extent of the Namibian MCS system it has been estimated that its cost is currently less than four percent of the landed value of the fisheries (Wiium and Uulenga 2002).

Monitoring, control and surveillance in Angolan waters was improved considerably with the installation of a VMS system in July 2000, which is applied to approximately seventy trawlers, although there is still a lack of patrol capabilities, especially in the most productive southern provinces, which limits it effectiveness. Lack of means for maintenance has put small patrol vessels out of action, and there is no long-range patrol vessel (SADC 2002). A key problem is the encroachment of trawlers into the 12 nm coastal zone designated for artisanal fishers, resulting in competition for resources and destruction of gear. Conflicts have escalated in recent years, with Spanish trawlers targeting shrimp and demersal fish implicated in many of the disputes (Lankester 2002), although competition for horse mackerel is also a problem (Sardinha 2001).

In South Africa 126 Marine Conservation Inspectors are responsible for law enforcement along a 3 500 km coastline and a 200 nm EEZ, an area in excess of 1 000 000 km2. In addition South Africa has distant water fishery responsibilities in the Marion/Prince Edward Island group. The vessels at their disposal are three old and unreliable patrol boats, with a 40 nm offshore limit, a few ski-boats and inflatables. Thus the South African authorities have not been able to conduct any offshore patrols since 1994, although fisheries inspectors are sometimes able to use naval vessels for patrols, and the South African Air Force carries out maritime patrols, including surveillance of fishing vessels.

A fishery compliance workshop held in 2000 identified problems in each fishery sector, and for the pelagic fishery these included widespread discarding as a result of a quota on sardine, size selection and by-catch limits; illegal fishing in closed areas; inadequate procedures for estimating catch composition; faulty weighing machines at offloading sites; attempted bribery of offloading control officers; and inspectors being provided with insufficient information concerning quota allocations (MCM 2000).

The situation has been receiving attention, and in order to increase manpower available for surveillance activities, cooperation with other law enforcement agencies has been improved, and control of landings is being outsourced to free up inspectors for patrols. In 2002 tenders were awarded for one offshore and three inshore patrol vessels, and a VMS system is planned for all commercial fishing vessels; the same system that is being implemented in Namibia.

2.4.4 States should cooperate

Lack of cooperation between states has been identified in some regions as a primary cause of overfishing, e.g. in European Union waters (Payne and Bannister submitted). In general cooperation between Angola, Namibia and South Africa is good, although the only formal bilateral agreement is between Namibia and Angola, who have only signed a Memorandum of Understanding to cooperate in fisheries research. Several regional agreements have recently been signed. The most important of these as far as fisheries within EEZs is concerned is the SADC Protocol on Fisheries, which was signed in August 2001 by the fourteen SADC members, although to date it has not yet been ratified by all. This protocol emphasises the “importance of fisheries in the social and economic well-being and livelihood of the people of the region, notably in ensuring food security and the alleviation of poverty” and aims to “promote responsible and sustainable use of the living aquatic resources and aquatic ecosystems of interest to State Parties...” It includes articles on international relations, management of shared resources, harmonisation of legislation, law enforcement, access agreements, high seas fishing, artisanal fisheries, aquaculture, protection of the environment, human resources development, trade and investment, science and technology, and information exchange, and closely follows internationally accepted practices as outlined in the major conventions.

While not strictly relevant to the near-shore small pelagics stocks, a notable recent development is the Convention on the Conservation and Management of Fishery Resources in the South East Atlantic Ocean, signed in April 2001 by Angola, the European Community, Iceland, Korea, Namibia, Norway, South Africa, United Kingdom (in respect of St. Helena and its dependencies) and United States. This convention aims to ensure the long-term conservation and sustainable use of high seas fishery resources in the convention area and straddling stocks (excluding tunas, which are covered by ICCAT), through the establishment of the South East Atlantic Fisheries Organization (SEAFO). This is the first RFMO established in terms of the UNFSA (Doulman 1999; Nichols submitted). The member states intend to cooperate to manage the fishery resources of the area, using the best scientific advice and on the basis of the precautionary approach. A scientific committee will be set up to promote research and formulate specific rules for the collection and analysis of data. Measures will be adopted concerning control and enforcement within the convention area, and a compliance committee will give advice and recommendations on matters pertaining to conservation and management measures. Duties of flag states and port states are laid down. Full recognition is to be given to the special requirements of developing states in the region with respect to the conservation, development and management of fishery resources.

The third international agreement worth mentioning here is the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD). This declaration arose from initiatives presented to the OAU[28] for the recovery and development of Africa and was adopted as Africa’s principal agenda for development, providing a strategic framework for the socio-economic development of the continent, within the institutional framework of the African Union. While the principle of partnership with the rest of the world is equally vital, it must be based on mutual respect, dignity, shared responsibility and mutual accountability. The expected outcomes include:

economic growth and development and increased employment;

reduction in poverty and inequality;

diversification of productive activities;

enhanced international competitiveness and increased exports;

increased African integration.

Whether NEPAD will have significant impacts on fisheries management in the near future is unclear, although it apparently helped Namibia’s request to allow its purse seiners access to South African sardine stocks (see 2.3.1).

Within the research field several cooperative initiatives have gained widespread praise. The Benguela Environment and Fisheries Interaction and Training Programme (BENEFIT) is a ten-year research programme that was started in 1997 by Angola, Namibia and South Africa, with several donor countries as cooperating partners, notably Norway and Germany. The overall goal of BENEFIT is to promote the sustainable utilisation of the living resources of the Benguela Current Ecosystem. As outlined in the 1997 Science Plan, this goal is to be achieved through an active science and technology programme integrated with capacity building within the Benguela region. Research is centred on fish resource assessment and monitoring of the environmental parameters related to the natural variability of those resources (from www.benefit.org.na).

A second programme that was also initiated by the three coastal states of the Benguela system is the Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem Programme (BCLME). This programme started in 2002 and aims to develop an integrated and co-ordinated ecosystem management approach. It is concerned with all activities relating to the marine system, including fisheries issues, the effects of other marine activities such as seabed mining, oil exploration and production, and coastal zone activities (for more information see www.ioinst.org/bclme).

Namibia and South Africa are also both full members of the two RMFOs; ICCAT and CCAMLR, while Angola is also a member of ICCAT.

2.4.5 Decisions should be transparent and states should make people aware of responsible fisheries

As noted in section 2.4.1, fisheries management in the Benguela region has been typically state dominated and top-down in structure. Involvement of stakeholders has been ad hoc and generally not formally structured. Section 2.4.1 also described some attempts by the national authorities to create greater participation in the management systems. Another aspect of transparency is the rights allocation process.

For decades the South African fishing industry was controlled by a few large, predominantly white-owned companies, and allegations of racism, nepotism and corruption were made concerning the allocation of rights. Government initiatives to increase black participation since 1996 resulted in litigation and limited success (from DEAT 2002b). There was obviously a need to revise the system, and in order to gain public support it had to be fair, but more importantly, it had to be seen to be fair. To this end the process was designed to be as transparent as possible.

A call for medium-term rights applications was made in 2001 and despite increasing the non-refundable application fee from N$ 100 to N$ 6 000 over 5 000 were received. Crucially, a set of policy guidelines was broadly advertised alerting applicants to the specific criteria that needed to be met. A Rights Verification Unit, an independent auditing firm, was set up, to receive the applications, verify the information submitted and to instil confidence that applications would not be lost or tampered with. The applications were then assessed by at least two members of an independent advisory committee, which consisted of people with no interests in the fishing industry. Finally the Ministry decided whether or not to allocate a right and all decisions were made public. Unsuccessful applicants had the right to appeal.

At the end of the process there was general agreement amongst the industry and the coastal communities that, although not perfect, the process was greatly improved, more balanced and more transparent than ever before (Moosa 2002). Despite this move towards transparency in the rights allocation system, the state has still been embroiled a series of litigations and a current case, if lost, may require the reallocation of the entire hake quota. Additionally, the public have complained that the “rules” for awarding rights were not made public and indeed the Marine Living Resources Act (RSA 1998) gives the Minister sole power in granting such rights. This final issue is similar to the Namibian system in which selection criteria “leaves a large measure of discretion to the Minister in granting rights” (Manning 2000).

2.4.6 Fisheries should be included in coastal management plans