Summary

The background of tuna management through regional tuna fishery management organizations (RTFMOs) is reviewed, acknowledging that, due to the highly migratory or mobile nature of tuna, management is best carried out throughout the range of the species, taking into account principles and provisions in recent international instruments. It is noted that while there has been a recent surge in development of national tuna management plans, activity has mainly been centred in the tuna-rich Pacific Island States of the Western and Central Pacific, in preparation for the establishment of the Western and Central Pacific Tuna Commission. General obstacles to management of tuna by RTFMOs are outlined, and issues and priorities for tuna management recently identified by the RTFMOs themselves presented, such as the need for more information and data, problems associated with IUU fishing and tuna trade. Steps being taken by RTFMOs to address specific management issues are described, including measures to implement recent international fishery instruments, develop catch certification and trade schemes and improve cooperation and coordination at regional level. Some paths to solutions were suggested, building on current initiatives and noting that this is a period of consolidation for the implementation of international instruments.

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1 International and regional considerations

The management of tuna, as highly migratory species, entered a new dimension with the adoption of the 1995 UN Fish Stocks Agreement. Building on elements of the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (“1982 Convention”), 1993 FAO Compliance Agreement and the 1995 FAO Code of Conduct for Responsible Fishing, it provides an extensive framework for management objectives, cooperation and consultation, and enforcement of fisheries for highly migratory species, including tuna.

The 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (“1982 Convention”), Article 64, charges coastal States and other States whose nationals fish in the region for highly migratory species with cooperating directly or with international institutions with a view to promoting optimum utilization, within and beyond the exclusive economic zone (EEZ).

Species of tuna defined as “highly migratory” in Annex 1 of the 1982 Convention are:

Albacore tuna: Thunnus alalunga.

Bluefin tuna: Thunnus thynnus.

Bigeye tuna: Thunnus obesus.

Skipjack tuna: Katsuwonus pelamis.

Yellowfin tuna: Thunnus albacares.

Blackfin tuna: Thunnus atlanticus.

Little tuna: Euthynnus alletteratus; Euthynnus affinis.

Southern bluefin tuna: Thunnus maccoyii.

One rationale for promoting such cooperation is the fact that tuna range throughout areas of national jurisdiction of many States, as well as the high seas; hence, cooperative/consultative management would appear to benefit the species. In addition, a significant tuna industry lobby of the era, primarily in the United States, did not favour recognition of coastal State jurisdiction over tuna in order to maximize fishing opportunities, and promoted representation of industry interests by their national State in the management of tuna occurring in the waters of other coastal States. This could be achieved by membership of their State in a regional organization mandated with setting management measures throughout the range of the species, including EEZs of coastal States. However, the coastal States insisted on sovereign rights over all species, including tuna. There were two conflicting approaches to the application of Article 64.

To resolve this conflict, in the South Pacific region, the 1988 Treaty on Fisheries between the sixteen member States of the South Pacific Forum Fisheries Agency (FFA) and the United States was concluded and is still in force. This early instrument provided precedent for a cooperative approach to the management of highly migratory fish stocks, while preserving the sovereign rights of coastal States.

When the 1982 Convention was signed, there were already three regional organizations established with a mandate focused on tuna fish, and three more have been established since then. In addition, establishment of a Commission for the Conservation and Management of Highly Migratory Fish Stocks in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean[38] is in preparatory stages. The organizations and date of establishment are as follows (see Annex 1 for details on the establishing instrument, membership and objectives of each).

Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission (IATTC), 1949;

International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT), 1966;

South Pacific Forum Fisheries Agency (FFA), 1979;

Western Indian Ocean Tuna Organization (WIOTO), 1991;

Indian Ocean Tuna Commission (IOTC), 1993;

Commission for the Conservation of Southern Bluefin Tuna (CCSBT), 1994.

Although its overall mandate is not focused on fish, or even tuna, the Secretariat of the Pacific Community (SPC), has carried out extensive research/technical programmes relating to tuna, and its work will be included in this paper.

The above bodies were established prior to the adoption of the UN Fish Stocks Agreement, but are actively engaged in implementing provisions of that instrument, as well as the other post-UNCED instruments, as noted in section 1.3.[39]

A new Commission will be established under the first post-1995 convention concluded implementing the UN Fish Stocks Agreement with respect to highly migratory fish stocks, the 2000 Convention on the Conservation and Management of Highly Migratory Fish Stocks in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean (“WCPT Convention”). It is the Commission for the Conservation and Management of Highly Migratory Fish Stocks in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean (“WCPFC”). It seeks to ensure the conservation of stocks and, in particular, to ensure that stocks are not overexploited by uncontrolled high seas fishing. The WCPT Convention, once it enters into force, will enable limits to be imposed on the amount of fish that can be taken, and on who has access to the tuna resource.

Because of these limits, access to the resource may become scarce and result in a substantial increase in the value of the resource.[40] Its key features include: a large geographical area to accommodate the entire migratory range of the stocks; a decision-making mechanism that includes a chambered voting system and conciliation procedure; binding dispute settlement; a Commission, Scientific Committee and Technical Committee; compliance and enforcement; and participation of Taiwan (Chinese Taipei).

The regional fishery bodies have been very active in addressing the issues in the post-UNCED international fishery instruments. A recent review was carried out by the author for FAO in respect of all regional fishery bodies (RFBs), including those noted above.[41] A questionnaire was distributed seeking information on: current issues of importance to the regional fishery body (RFB); implementation of post-UNCED international fishery instruments, including the four International Plans of Action (IPOAs); and action taken on the following specific issues: implementation of the precautionary approach; addressing ecosystem based fisheries management; assessment of the extent, impact and effects of IUU fishing in its area of competence; strengthening the RFB’s capacity to deal more effectively with conservation and management issues; addressing issues relating to capacity; accommodating new entrants and catch certification and documentation.

Tables showing the responses of the tuna RFBs noted above appear in Annexes 2, 3 and 4 respectively. The responses will be analysed in section 2 of this paper, within the framework of the components of sustainability.

1.2 National activities

Tuna management by individual States has, in many cases, been enhanced by the 1995 Fish Stocks Agreement. For example, as part of the process to establish the WCPFC, Pacific Island States have been adopting Tuna Management Plans and revising their laws accordingly.[42] The US Pacific Fishery Management Council has developed a comprehensive Fishery Management Plan for Highly Migratory Species, with the lead goal being to “promote and actively contribute to international efforts for the long-term conservation and sustainable use of highly migratory species fisheries that are utilized by West Coast-based fishers, while recognizing these fishery resources contribute to the food supply, economy and health of the nation”.[43]

Australia provides an example of a country that is developing two different rights-based approaches to managing tuna longline fleets for the west and east coast tuna longline fisheries. The west coast tuna fishery will be managed using a system of individual transferable catch quotas (ITQs), while the east coast will go the route of input controls, using limits on the numbers of branchline clips (hooks) to be used by each operator. These approaches are designed to meet the ecological sustainable development (ESD), economic efficiency and other legislative objectives that apply to both fisheries and were developed using extensive stakeholder consultation.[44]

Another approach is being taken in a major tuna fishing and consuming nation, Japan. An Organization for the Promotion of Responsible Tuna Fisheries (OPRT) representing all stakeholders in tuna fisheries[45] has recently been established,[46] with the objective of contributing to the responsible development of tuna fisheries and promoting sustainable use of tunas. Its first major project is to world towards the elimination of all flag of convenience tuna longline vessels carrying out illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) tuna fishing. To do this, it has a program to buy and scrap IUU vessels, and is working to ensure that tuna imports into Japan (the world’s largest sashimi tuna market, 60 percent of which is imported) do not include fish from IUU vessels.[47]

1.3 Rationale for regional focus in paper

While recognizing the broad scope of diverse national initiatives regarding tuna management, this paper will focus on the work of regional organizations as representative of tuna management. As evidenced in Annex 1, the membership of the regional tuna fishery bodies is wide-ranging, and their different mandates and collective decisions and actions represent ways of addressing factors of unsustainability and overexploitation in tuna fisheries.

In particular, the implementation by regional tuna fishery bodies of the international instruments reflects the priorities of their members’ countries. Annex 3 shows that all bodies - with the exception of FFA which does not engage directly in fisheries management[48] - are taking steps to implement the 1993 FAO Compliance Agreement and the International Plan of Action on Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing (“IPOA-IUU fishing”). Most (four in each case) are taking steps to implement the 1995 UN Fish Stocks Agreement and 1995 FAO Code of Conduct for Responsible Fishing, as well as the IPOAs on the Conservation and Management of Sharks and the Management of Fishing Capacity. Only two report action to implement the IPOA on Reducing the Incidental Catch of Seabirds in Longline Fisheries.

Another compelling reason for focusing on regional management is the fact that tuna are highly migratory, and analysis from individual coastal State/fishing State-or-entity perspective can only provide a partial snapshot of management throughout the range. Regional bodies encounter the full range of obstacles and challenges in their management or related activities.

1.4 The Resource

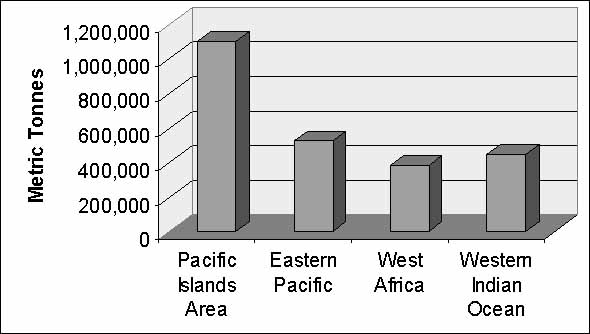

There are four major tuna fishing areas in the world, shown in Figure 1: the Pacific Islands, the eastern Pacific (average annual tuna catches of about 525 000 mt), West Africa (385 000 mt), and the western Indian Ocean (450 000). The Pacific Islands fishery dwarfs the other three in volume (see graph) and because a large component of the catch is for the high value sashimi market, the relative value of the Pacific Islands tuna is even higher.[49] An Asian Development Bank Report noted that the value of tuna catch in the region increased from about US$ 375 million in 1982 to US$ 1.2 billion in 1993, US$ 1.6 billion in 1994, US$ 1.7 billion in 1995 and US $1.9 billion in 1998.[50]

Figure 1. The World’s Major Tuna Fishing Areas[51]

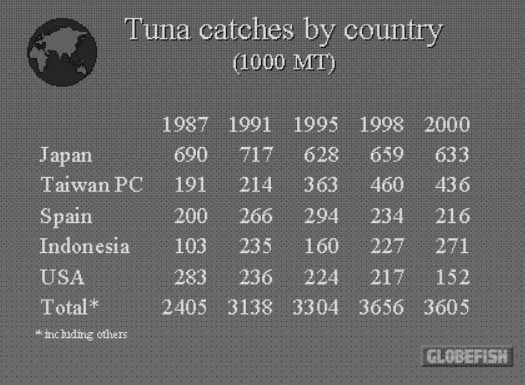

Industrial tuna fishing is carried out mainly by distant water fishing nations including China, Japan, Taipei (China), Spain, Indonesia and the United States, shown in Figure 2. Japan continues to be the world’s major tuna catching country, but catches have contracted in recent years.[52]

Taiwan (Province of China) more than doubled its catch during the years under review from 190 000 MT to 460 000 MT in 1998, but also Taiwan (Province of China) experienced a decline in 2000. Noteworthy is the increase in tuna catch during the years under review of Indonesia (+130 percent). The loss of the tuna fishing grounds in the Central Eastern Pacific due to the tuna dolphin issue led to a substantial decline in US tuna production, down almost 50 percent

Figure 2. Tuna catches by country[53]

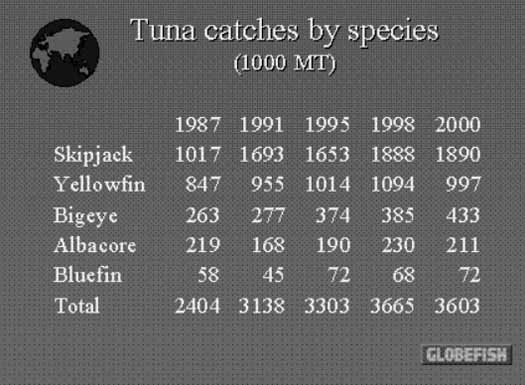

Figure 3. shows that skipjack is by far the main species caught, and catches increased by 80 percent over the past decade. In 1999, skipjack catches reached a peak of almost two million MT.

Yellowfin is the second major species, also growing, but at a slower path than skipjack. This species is generally higher priced than skipjack, also used in canning. In 2000, yellowfin catches declined by ten percent over 1999 to about one million MT.

Albacore catches were stable over the years, while bigeye catches went up. For bigeye there is concern about over-fishing.

Figure 3. Tuna Catches by Species[54]

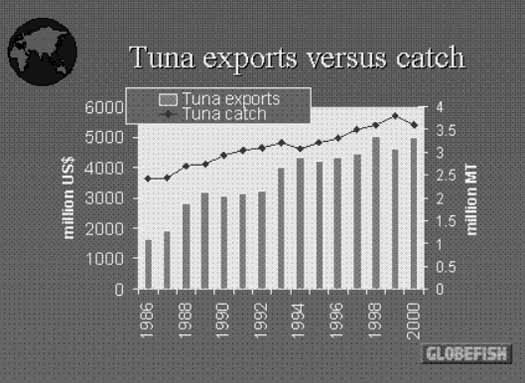

The graph in Figure 4. compares the growth in tuna catch (in quantity terms) with the growth of tuna exports (expressed in value terms). It can be noted that trade expanded more than catch, reflecting increase in value of both fresh and frozen tuna in recent years. It has to noted, however, that the trade figures have not been adjusted for inflation. In 1999, the oversupply of tuna shows that while catches reached a record of 3.8 million MT, the total value of tuna trade was lower than in 1998 or 2000.

Figure 4. Tuna exports versus catch.[55]

Figure 5 - Summary and Outlook[56]

The biological aspects of the fishery are thoroughly reviewed in Dr Fonteneau’s paper in this document. In more general terms, Figure 5. indicates that catch reduction has been successful, but the source, GLOBEFISH, does not provide such scientific details. However, it also indicates that bluefin and bigeye are under stress. This is reinforced by scientific advice provided to regional fisheries management organizations. For example, the Scientific Committee of the CCSBT advised in October 2002 that at a global catch of about 15 500 tonnes there was an equal probability that the bluefin stock could decline or improve. It was acknowledged that at current catch levels there is little chance that spawning stock will be rebuilt to the 1980 levels by 2020.[57]

A report of the Oceanic Fisheries Programme at the SPC[58] notes in respect of bigeye tuna in the western and central Pacific Ocean that biomass in the 1990s is estimated at approximately 35 percent below the level it would have been if fishing had never occurred. It concludes that overfishing has not yet occurred, but notes as a continuing concern that a significant part of the increase is attributable to the Philippines and Indonesian purse seine fisheries, which have the weakest size, effort and catch data. In the eastern Pacific, the IATTC assesses the status annually and has adopted quotas and restrictions on floating objects, and the Pacific Fishery Management Council reports that the stock in the eastern Pacific appears to be near the level that produces MSY.[59] However, there is concern over increased fishing on juveniles since the advent of the expanded fishery targeting tuna by sets on floating objects.

It should be noted that other tuna resources had been under stress prior to the initiatives at regional and international level to ban or place a moratorium on driftnet fishing. The 1989 Wellington Convention on driftnet fishing was agreed in direct response to a rapid build-up of the driftnet fishing fleet[60] for southern albacore tuna. Scientific advice indicated that if fishing were to continue at existing levels, the stock would be threatened with collapse within two years.

2. IS FISHERY MANAGEMENT SUCCESSFULLY ACHIEVING THE FOUR COMPONENTS OF SUSTAINABILITY?

2.1 Relevant background - regional organizations

The framework for this paper seeks an evaluation as to whether the fishery management organization “understands” the aims of the various components of sustainability: bio-ecological, social, economic and institutional. In the case of regional fishery bodies, there may be an understanding of what their aims should be, but their mandate may limit their actions in fulfilling the aims. In one case - the IATTC - this has been recognized and the Convention is being renegotiated to strengthen the conservation and management program. In another - the IOTC - it is observed that although the 1995 UN Fish Stocks Agreement may encourage some non-members to accede, the Commission is not mandated by all its members to pursue implementation.[61] The latter indicates issues such as industry pressure, lack of political will or other factors may be operating to discourage steps to implement the Agreements.

There are a range of problems that RFBs with management mandates share, including the regional tuna management organizations. These are noted below under the various components of sustainability, but in general concern is shared in relation to issues such as: membership/participation in the management regime may not include all fishing States or entities; difficulties/inability of members to agree on management measures; reporting/data collection/research a problem from members (and non members); weak implementation of decisions; difficulties to implement controls at sea or in ports; inability to inspect landings and enforce/prosecute; divergent interests of coastal and fishing States; and no exhaustive list of registered vessels.

It is in this context that the main objectives and activities of each RFB will be described, before reviewing the activities under each of the four components. The aims and actions of each body can therefore be better understood.

CCSBT

The objective of the Convention is to ensure, through appropriate management, the conservation and optimum utilization of southern bluefin tuna (SBT). The functions of the Commission include: (i) collecting, analysing and interpreting scientific and other relevant information on SBT, and (ii) adopting conservation and management measures including the total allowable catch and its allocation among the Members. Other additional measures may also be adopted by the CCSBT. The species covered by the Convention is SBT, and the Commission is also responsible for collecting information on "ecologically related species" defined in the Convention as living marine species which are associated with southern bluefin tuna, including but not restricted to both predators and prey of SBT.

FFA

The objectives of the Convention are: (i) conservation and optimum utilization of the species covered by the Convention; (ii) promotion of regional cooperation and coordination in respect of fisheries policies; (iii) securing of maximum benefits from the living resources of the region for their peoples and for the region as a whole and in particular the developing countries; and (iv) facilitating the collection, analysis, evaluation and dissemination of relevant statistical scientific and economic information about the resources covered by the Convention. The functions of the Agency include, inter alia: (i) harmonization of policies with respect to fisheries management; (ii) cooperation in respect of relations with distant water fishing countries; (iii) cooperation in surveillance and enforcement; (iv) cooperation in respect of onshore fish processing; (v) cooperation in marketing; (vi) cooperation in respect of access to the 200 mile zones of other Parties. The species covered by the FFA are the highly migratory species of tunas, primarily skipjack, yellowfin, bigeye and albacore.

IATTC

The main objectives of the Convention are to maintain the populations of yellowfin and skipjack tuna and other kind of fish taken by tuna fishing vessels in the eastern Pacific and to cooperate in the gathering and interpretation of factual information to facilitate maintaining the populations of these fishes at a level which permits maximum sustainable catches year after year. The functions of the Commission include inter alia (a) to gather and interpret information on tuna, (b) to conduct scientific investigation concerning the abundance, biology, biometry, and ecology of yellowfin and skipjack tuna in the Convention Area, and to recommend proposals for joint action for conservation. The Commission has regulatory powers and catch quotas for yellowfin tuna have been set by the Commission since 1962. Since 1976, the Commission has implemented a programme on tuna dolphin relationship and since 1992 it has developed an International Dolphin Conservation Programme aiming at progressively reducing dolphin mortality in tuna fishing. The Commission also serves as the Secretariat for the Agreement on the International Dolphin Conservation Program, whose principal objective is to reduce and strictly regulate accidental dolphin mortality which occurs in the purse seine fisheries for tuna. The species covered by IATTC are all tunas and other fish taken by tuna fishing vessels.

ICCAT

The main objective of the Convention is to maintain the populations of tuna and tuna-like species found in the Atlantic at levels which permit the maximum sustainable catch for food and other purposes. The Commission's functions inter alia include: (i) to study the populations of tuna and tuna-like fishes, (ii) to collect and analyse statistical information relating to the current conditions and trends of the tuna fishery resources of the Convention Area, and (iii) recommend studies and investigations to the Contracting Parties.

The species covered by the Commission are the tuna and tuna-like fishes (the Scombrioformes with the exception of the families Trichiuridae and Gempylidae and the genus Scomber) and such other species of fishes exploited in tuna fishing in the Convention Area as are not under investigation by another international organization. The Commission has no regulatory powers, but makes regulatory recommendations to be implemented by Contracting Parties, but these are subject to an objection procedure. ICCAT has recommended a number of measures on catch quotas, minimum weight of fish and limitation of incidental catches, as well as IUU fishing.

IOTC

The main objectives of the Agreement are to promote cooperation among members with a view to ensuring through appropriate management, the conservation and optimum utilization of stocks as well as to encourage sustainable development of fisheries based on them. The Commission may be a two-third majority of the Members present and voting adopt conservation and management measures binding on its Members. Such regulatory measures are subject to objection procedure. The species covered by the Convention are as follows: yellowfin tuna, skipjack tuna, bigeye tuna, albacore, Southern bluefin tuna, longtail tuna, kawakawa, frigate tuna, bullet tuna, narrow-barred Spanish mackerel, Indo-Pacific king mackerel, Indo-Pacific blue marlin, black marlin, striped marlin, Indo-Pacific sailfish, and swordfish.

SPC

The main objective of the Agreement is to encourage and strengthen international cooperation in promoting the economic and social welfare and advancement of the peoples of the South Pacific region. The Divisional goal for fisheries is to provide a regional service which provides information, advice and direct assistance to the Pacific Community through SPC member governments, either individually or collectively, in using living marine resources in the most productive and responsible manner possible. Activities include fisheries stock assessment (for both reef fisheries and highly migratory fish stocks), marine ecosystem research for reef and pelagic fisheries, small scale tuna fisheries development support, coastal fisheries management support and fisheries information and databases within the area of competence.

The Commission operates a Coastal Fisheries Programme covering all living aquatic species subject to subsistence and commercial fishing and aquaculture, and an Oceanic Fisheries Programme which deals with tuna, billfish and related species. The goals and objectives are described below.

Coastal Fisheries Programme

The goal is to optimise long-term social and economic value of small-scale fisheries and aquatic living resource use in Pacific Island waters, with the following objectives:

a regional support framework for economically, socially and environmentally sustainable aquaculture planning, research and development by Pacific Island governments and private enterprises;

economically-viable and environmentally sound Pacific Island fishing enterprises;

environmentally sound and socio-economically achievable governance of reef and lagoon fisheries;

fishing sector human resource and technical skills development;

scientifically rigorous information on the status, exploitation levels and prospects of the coastal resources managed by Pacific Islanders; and

easily-available, relevant and understandable aquatic living resource-based knowledge for member countries and territories.

Oceanic Fisheries Programme

The goal is to provide access to Pacific Island countries and territories (PICT) of the best available scientific information and evidence necessary to rationally manage fisheries exploiting the region’s resources of tuna, billfish and related species, with the following objectives:

comprehensive regular assessments of status and prospects of oceanic fisheries for Pacific Island Countries and Territories (PICT) fisheries departments and regional processes;

oceanic fishery data collection and analytical support to PICT fisheries departments; and

understanding pelagic ecosystems in relation to tuna and associated species stocks.

Information included under each component below is sourced from the responses of the secretariats of the RFBs to the recent survey carried out for FAO.[62] It is emphasized that the member countries did not formally consider the responses, which are to be understood only as indicative of trends in tuna management. In addition, the information may be incomplete, as it is based on the questions and responses, rather than a comprehensive analysis of documents and activities of each RFB. However, it does provide useful insights in relation to the issues in this paper. The information is presented in three parts under each:

Indicative issues important to the RFBs: The RFB Secretariats were requested to identify the five most important issues for them, and the reasons why they are important. If an RFB did not indicate an issue as a priority, this does not necessarily mean the issue is unimportant for the RFB. A summary of the issues identified by the RFBs appears in Annex 2.

Implementation of Post-UNCED international fisheries instruments: Respondents were requested to provide information regarding recent activities, priorities or plans to implement the post-UNCED international fishery instruments.[63] A summary appears in Annex 3.

Addressing specific issues: Respondents were requested to indicate if their RFB has recently undertaken any activity, priorities or plans in relation to certain issues described in section 1.1. A summary of the specific issues and responses appears in Annex 4.

2.2 Bio-ecological Component

The bio-ecological component of sustainability embraces the aim to protect, conserve and restore fishery resources, the environment, habitat and ecosystem and biodiversity. It includes the prevention of overfishing and the restoration of resources, habitats and ecosystems to conditions capable of producing maximum sustainable yield (MSY), taking into account multispecies and ecosystem considerations.[64]

2.2.1 Priority Issues for RFBs

Priority bio-ecological issues identified by three RFBs are implementing responsible fisheries management and two identified applying the ecosystem approach to fisheries management and by-catch issues. This mirrors the trend in the main study, and is consistent with prominent issues in recent international instruments, which in turn responded to broad international concern.

Regarding responsible fisheries management, this would include establishing management measures for sustainable fisheries including TACS, and effort control and other measures.

CCSBT referred to the fact that the southern bluefin tuna (SBT) stock has been fished to low historical levels, and the consequent importance of setting a TAC for its management and conservation objectives.

IOTC noted difficulties in the allocation of resources, and the need to determine principles for that purpose. Its Agreement guarantees a share to coastal States and DWFNs invoke historical rights based on past exploitation levels or capacity. This issue is complicated by reflagging of IUU fleets in non-coastal States, often with open registries, some of which are seeking contracting or cooperating status in the Commission. IOTC also noted that a substantial part of the catch is unreported.

Ecosystem issues are addressed by ICCAT, which has added ecosystem issues to its agenda to monitor developments for management purposes. SPC noted the need to understand the broader large marine ecosystem supporting the managed species, and links this with the hitherto lack of detailed information on the potential significance of tuna fishery by-catch. IATTC has also noted the need to control by-catch.

2.2.2 Implementation of post-UNCED International Fishery Instruments

This section addresses implementation of the three main instruments - the Compliance Agreement, Fish Stocks Agreement and Code of Conduct - and the species-related IPOAs (incidental catch of seabirds, management of sharks).

The CCSBT is taking account of all post-UNCED fishery instruments in the implementation of its management and conservation objectives, as noted in this and the other components as described below. Activities in this regard relating to the bio-ecological component include:

fishing activity is being managed at levels consistent with the scientific advice;

the CCSBT has a working group focusing on ecologically related species and has taken decisions to require members to fish responsibly; and

The post-UNCED fishery instruments are not directly relevant to FFA, because it does not have a mandate to adopt conservation and management measures and therefore is not a management organization. However, the instruments are relevant to members’ national activities and legislation, and to the WPTC. FFA’s role is to assist its member countries as noted above and in the work of the Commission.

To implement the 1993 FAO Compliance Agreement, The IATTC Commission has developed a regional register that lists vessels that are authorized to fish in the area of the Agreement. It has also agreed to establish a list of vessels that are not authorized to fish in the area of the Agreement and are undermining the Agreement and the conservation and management measures.

Currently IATTC members are negotiating a new Convention that will take into account, among other things, many of the relevant principles of the 1995 UN Fish Stocks Agreement. Only two members of the IATTC have ratified the Agreement, but many of the key provisions of the Agreement have been incorporated into the draft negotiating text for the new Convention.

The IATTC has not adopted specific measures to promote the application of the 1995 Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries. However, the relevant portions of the Code of Conduct often serve as a guideline for the consideration of the Commission’s conservation and management resolutions, and most, if not all, of the resolutions adopted by the parties to the IATTC are drafted in accordance with the principles of the Code.

Regarding the IPOA on the Conservation and Management of Sharks, the IATTC has adopted a measure requiring purse seine vessels to promptly release unharmed, to the extent practicable, all sharks taken incidentally. The Commission has also taken action to enhance the collection of shark by-catch information.

ICCAT indicates its implementation of the post-UNCED fishery instruments by including post-UNCED fishery agreements on its website. The number of resolutions and recommendations adopted annually by ICCAT has increased dramatically over the past decade. Many of these support the post-UNCED Fishery Instruments.

Regarding the 1993 FAO Compliance Agreement, the IOTC Secretariat is collecting data on all tuna fishing vessels in the Indian Ocean and coordinating this activity with FAO and the other tuna regional fisheries management bodies.

Although the 1995 UN Fish Stocks Agreement may encourage some non-members to accede to IOTC, the Commission is not mandated by all its members to pursue implementation.

The IPOA on Reducing the Incidental Catch of Seabirds in Longline Fisheries is only an issue in the temperate zone, where IOTC recognises the priority of CCSBT in the management of southern bluefin tuna.

Regarding the IPOA on the Conservation and Management of Sharks, the IOTC Commission has authorised the Secretariat to collect statistical data on non-target, associated and dependent species, including sharks. This does not go the extent of conducting stock assessment because the Agreement provides a mandate on only 16 tuna and tuna-like species.

The SPC supports its members extensively in the implementation of the 1995 FAO Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries, including dealing with small-scale fisheries and aquaculture.

Some assessments and observer data analyses, have been carried out on incidental seabird catch, and it was recognised that this is not a problem in the current fisheries within the SPC mandate area.

SPC is undertaking some assessments on the conservation and management of sharks, based on observer data and improvement of by-catch reporting by fishing fleets. Current indications are that Pacific pelagic shark catches are within sustainable limits. SPC

SPC’s focus will be also on some other more fragile by-catch species, including turtle. Awareness materials have been produced on the general by-catch issue (including sharks), and one of the main aims of the SPC Fisheries Development Section is to promote tuna fishing methods by Pacific Islanders that mitigate by-catch.

The SPC’s mandate does not extend to managing fishing capacity or implementing the Compliance Agreement.

2.2.3 Addressing Specific Issues

The IATTC has addressed the matter of ecosystem-based fisheries management in the formulation of relevant conservation and management measures. Thus, in considering measures for yellowfin and bigeye tuna, the two principal species currently being managed by the Commission, the impact on all species of tuna in the same ecosystem is taken into account. Further, the Commission has adopted resolutions regarding by-catch that are designed to address ecosystem management by requiring specific measures to reduce the by-catch of species taken in the tuna purse seine fisheries. This has included the development of ecosystems models for the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean.

Also, IATTC members are currently negotiating a new Convention which will strengthen further the conservation and management program.

SPC’s work is oriented towards ecosystem-based fisheries management in the context of the Oceanic Fisheries Programme on ecosystem understanding, supported by the EU and GEF, and of the reef fisheries work.

2.3 Social component

The main social aims of sustainability are to achieve optimum utilization of the resource, ensure safe, healthy and fair working environments and conditions, consider aquaculture as a means to promote diversification of income and diet and assist developing countries.

Most of the regional tuna organizations are not specifically mandated to achieve these aims. However, in the Western Central Pacific the technical work of the SPC does include aquaculture and obtaining information on subsistence village “IUU fishing”. The need to guide increasing aquaculture investment into economically and socially sustainable channels was cited by SPC.

SPC also referred to assisting member States with the change in balance between subsistence and commercial fisheries. In this regard, an attendant need was identified to develop environmentally sound small scale coastal-based fishing enterprises, working in collaboration with the larger-scale tuna fisheries economic development work of FFA.

FFA cited tuna industry development and conflict management between artisanal and industrial fisheries as current issues. In relation to the former, FFA reported that its members are determined to see more private sector tuna-based economic activities, and to improve their domestic retention of economic and social benefits from the tuna industry. FFA will assist this by providing or coordinating expert advice in particular areas of interest.

Assistance to developing countries is high on the agenda of the organizations whose membership is comprised of developing countries. FFA and IOTC referred to a need for capacity building and financial support for fisheries administration in their member States.

2.4 Economic Component

The main economic aims are to match fishing capacity to the productive capacity of the resources, the environment and the ecosystem, to conduct trade according to World Trade Organization rules, including the elimination of subsidies, and to prevent illegally caught fish from reaching their markets.

2.4.1 Priority Issues for RFBs

Increasing fishing capacity of the fleets was cited by IATTC as a priority issue, which noted that the fleet should be controlled for reasons of conservation.

While prevention of illegally caught fish from reaching their markets is important for some bodies, it is discussed in the context of IUU fishing under section 2.5.

2.4.2 Implementation of post-UNCED International Fishery Instruments

In relation to the IPOA on the Management of Fishing Capacity,

The members of the IATTC Commission reached agreement in June of 2002 on the limitation of fishing capacity in the Eastern Pacific Ocean (EPO). The Commission has established a Permanent Working Group on Fleet Capacity and is considering a draft Plan of Action on the management of fishing capacity for the EPO.

Resolutions have been taken by IOTC to prevent capacity increase in certain targeted stocks. There have also been repeated calls for fleet reductions. The Secretariat is collecting data on all tuna fishing vessels in the Indian Ocean.

2.4.3 Addressing Specific Issues

A comprehensive trade information scheme is in place in CCSBT member countries. The IATTC is currently considering the adoption of a catch certification and documentation scheme for Bigeye Tuna

Regarding fleet capacity issues,

the CCSBT uses voluntary quotas but individual members have reduced capacity to assist with the containment of catch to such quotas;

the IATTC has established a Permanent Working Group on Fleet Capacity and consideration of a draft Plan of Action on the management of fishing capacity for the EPO.

assessment of effort by IOTC is addressed actively as a complement to vessel listings.

SPC advises countries during the course of developing national fishery development strategies, with the underlying philosophy that capacity should be incremented gradually. Further, SPC advises that actual fishing mortality should be reassessed after every new increment of fleet capacity, in relation to estimated sustainable limits. This is the preferred alternative to approving as many licences as possible, assessing the impact and then realizing that cut-backs are necessary; it promotes both sustainable local industry development and conservation. SPC does not certify catches, but monitors them as much as possible through the SPC Pacific Islands-based Port Sampling Programme.

2.5 Institutional Component

The main institutional aims are to use the best scientific information in a range of contexts, apply the precautionary approach, MCS both in-zone and on the high seas; cooperate with States and RFMOs to promote conservation and responsible fishing and resolve disputes peacefully, implement decision making processes and involve interested parties, education and training, and to take account of multiple use of coastal areas.

2.5.1 Priority Issues for RFBs

IUU fishing was named by a number of RFBs as an important issue. Concern was expressed about the level of unreported catches[65] and extent and impact of IUU fishing.[66] One RFB attributes the unreporting in its area of competence to the fact that the vessels concerned are flagged in open registry countries.[67]

Conflicts of interest at national level are a problem stated by one RFB.[68] Conflicts between the industry/environmental interest groups at national level leads to a reluctance to take specific management measures, although the principle behind these measures might have been adopted through ratification of overarching international instruments. It may also lead to a reluctance to monitor compliance through third party VMS or observer coverage.

For science-related issues, RFBs centred their responses around practical issues, including the need for continuing, accurate, comprehensive stock assessments.[69] Some RFBs were concerned about statistical databases. They pointed to the need for timely statistics and submission, collection and distribution of information.[70] One RFB focused on the need for a general Scientific Research Programme.[71]

On institutional issues, for one RFB the work begins at home; the important issue was reported as fostering solidarity, political will and cooperation among members[72]. Some RFBs identified related financially-based issues, the need for capacity building/financial support for fisheries administrations in member States.[73]

Linked to the financial and capacity issues is human resource development. One RFB is concerned about the need to develop a specialized human resource cadre in fisheries in member States to lessen the reliance on international and regional assistance, and to fulfil their own stewardship obligations in areas where there is no international or regional assistance.[74]

Another area of concern is information and communication. Information exchange among member States, between the member States and the organization,[75] its communication to decision-makers[76]

Some RFBs cited membership concerns as an important issue for them. This includes fishing by non-members[77], and broadened participation in the RFB.[78] One identified renegotiation[79] of a Convention as important.

2.5.2 Implementation of post-UNCED International Fishery Instruments

The CCSBT is taking account of all post-UNCED fishery instruments in the implementation of its management and conservation objectives. Activities in this regard include the following.

expert scientific advice is collected to inform decision making;

fishing activity is being managed at levels consistent with the scientific advice;

IUU fishing has been targeted and appears to have been affected significantly by the CCSBT trade information scheme;

publicity material is being prepared to educate SBT fishers about sharks and seabirds associated with the fishery.

The IATTC has taken measures in order to combat IUU fishing in the Eastern Pacific Oceans (EPO), such as developing a Regional Register of vessels that are authorized to fish for species under the purview of the Commission, establishing a permanent working group to deal with IUU fishing on a regular basis, and the adoption of resolutions, intended to discourage IUU fishing, regarding fishing by non-parties. The Commission recently agreed to develop a list of non-cooperating vessels, and is in the process of preparing such a list.

ICCAT adopted a Resolution adopted at its Ninth Special Meeting (Madrid, November-December, 1994), Regarding the Agreement to Promote Compliance with International Conservation and Management Measures by Fishing Vessels on the High Seas, which states that the Contracting Parties should take the necessary measures as soon as possible to maintain a register of all high seas fishing vessels greater than 24 meters in length and provide ICCAT with this information annually. ICCAT encourages non-Contracting parties to do the same. In 1999, ICCAT published a list of around 340 longline tuna fishing vessels claimed to be involved in IUU fishing and flagged to countries operating open registers.

The ICCAT Resolution Concerning the Unreported and Unregulated Catches of Tunas by Large-Scale Longline Vessels in the Convention Area adopted at the 11th Special Meeting in Spain, 1998 requires the Commission to request the Contracting Parties, Cooperating Parties, entities or fishing entities which import or land frozen tuna and tuna-like products to submit specified information on an annual basis. The Compliance Committee and Permanent Working Group for the Improvement of ICCAT Statistics must then identify those whose vessels diminish the effectiveness of management measures. ICCAT may then request the revocation of their vessel registration or fishing licenses.

IOTC action in support of the IPOA-IUU fishing has included listings of vessels aimed at identifying IUU fishing vessels, port State control and trade documentation schemes. Establishment of a Compliance Committee is planned.

Regarding IUU fishing on the high seas, SPC is promoting responsible management of Pacific Islands open registries through the Divisional Maritime Programme Legal Section, and working towards instituting more formal mechanisms for provision of catch-effort information on high seas fisheries in the region through the Oceanic Fisheries Programme Statistics Section.

2.5.3 Addressing Specific Issues

The implementation of the precautionary approach is carried out by RFBs as follows:

through the CCSBT’s scientific processes and the setting of voluntary catch limits by members on the basis of that advice;

the IATTC manages the fisheries utilizing precautionary principles and is in the process of incorporating a more formal procedure of scientific advice that utilizes the precautionary approach;

ICCAT has established an ad hoc working group on the precautionary approach;

IOTC reported that the implementation of a precautionary approach to fisheries management is reflected in the acceptance of the principle of incorporating uncertainty in stock assessments, but this has not been implemented to date. Operational models will be used to assess the consequences of management;

implementation of the precautionary approach underlies all of SPC’s activities, advice to its members and relations with other regional organizations; SPC advocates a precautionary approach in relation to both resource exploitation and social aspects of fisheries. This means that a reasonable doubt about the sustainability of the fishery must exist before the precautionary approach can be invoked. If this reasonable doubt cannot be established, and if there is reasonable doubt that peoples’ basic livelihoods will be affected by a closure, then the criteria for invoking the precautionary approach would not be met.[80]

Ecosystem management is included in the work of RFBs as follows:

ICCAT’s Standing Committee on Research and Statistics has a subcommittee on the Environment, which studies the effects of fisheries on the environment;

for IOTC, ecosystem-based fisheries management is pursued through requesting data on NTADs (however, it is rarely available), observer coverage of about ten percent of vessels, and assessment of FAD deployment through tagging;

Approaches to address the concerns surrounding IUU fishing include the following:

the extent, impact and effects of IUU fishing has been quantified by the members of CCSBT from domestic data and the Commission’s trade information scheme;

FFA provides some services to its members allowing them to assess the extent, impact and effects of IUU fishing, such as operation of a regional Vessel Monitoring System;[81]

one of the main responsibilities of the IATTC Working Group on Fishing by non-parties is to assess the extent and impact of IUU fishing in the area of the Agreement;

ICCAT has a scheme for port inspection as well as a Compliance Committee. ICCAT also has a Permanent Working Group on ICCAT Statistics and Conservation Measures, and the Standing Committee on Research and Statistics (SCRS);

IUU catches are routinely estimated by IOTC from vessel listings, activity reports (port visits) and trade documents.

To strengthen the RFB’s capacity to deal more effectively with conservation and management issues, the following steps have been taken:

the CCSBT has developed a scientific research program to support stock assessment and management decisions;

in ICCAT, two special Working Groups have been established: Working Group on Allocation Criteria and Working Group to Develop Integrated Monitoring Measures;

in IOTC, funds have been secured from extra-budgetary sources for improvement of coastal State statistical systems and for tagging;

SPC is continually expanding in size, and undertakes strategic planning to develop strengthened organizational capacity.

In accommodating new entrants into the fishery:

the CCSBT has actively encouraged membership to accommodate new entrants. The Fishing Entity of Taiwan was admitted to the Extended Commission in August 2002. Encouragement is currently being given to South Africa and Indonesia to take up membership;

in IATTC, new entrants have been accommodated, with several new members joining the Commission in the recent past;

IOTC encourages participation of States with financial constraints under the status of Cooperating Non-Contracting Party.

3. WHY IS FISHERY MANAGEMENT SUCCESSFUL (OR NOT)?

3.1 Successful Management?

The factors of unsustainability do not generally apply to tuna fisheries, because current information indicates that tuna stocks appear to be relatively healthy on a global basis, except for bluefin and bigeye, high value stocks which are under some stress. But it would not be wise to conclude that this is due to good fishery management. At national coastal State level, there has been scarce evidence of long-term tuna management: first there was industry-motivated non-recognition of coastal States’ rights (and therefore management responsibilities) over tuna for many years after the adoption of the 1982 Convention. There is also the fact that national tuna management plans have proliferated only in the past few years, and in respect of the western central Pacific region this was in response to the development of the WCPT Convention.

At national level for some of the major tuna-fishing DWFNs, there is widespread concern about the absence of control over their tuna fleets, resulting in IUU fishing, non-cooperation with management measures set by RFBs and failure to join or observe at relevant RFBs. These are some of the key reasons that bluefin and bigeye stocks are declining.

At regional level, the mandates of most tuna RFBs were developed prior to the implementation of the 1995 UN Fish Stocks Agreement, and other post-UNCED international fishery instruments. However, they all appear to be involved in implementing as much of each instrument as their capacity, members and mandates permit. This has led to some success, especially in the western central Pacific which produces most of the world’s tuna catch. Regional solidarity has been fostered by the FFA, even though it is not a “fisheries management organization” with a mandate for management measures. Some of its exemplary achievements have included the well-known Regional Register of Foreign Fishing Vessels, regional Treaty on Fisheries with the United States, minimum terms and conditions of fisheries access, cooperation in VMS and MCS, implementation of international instruments in national laws, active advice and analysis of markets and economics, providing advice in the development of domestic fishing industries, and serving as the region’s Secretariat during the development of the WCPT Convention.

More generally, there have been successes in curbing IUU fishing (including “flag of convenience” fishing) through trade schemes, an increasing trend to set up registers and develop relevant information bases on vessels authorized to fish, and to share information as appropriate.

RFBs generally noted progress in identifying their priorities in implementing responsible fisheries management, using precautionary and ecosystem approaches to management, addressing by-catch issues, negotiating a new instrument to improve conservation and management; assisting in the implementation of robust laws, increasing membership and relations with other bodies and non-contracting parties; establishing scientific and research programmes, promoting aquaculture and industry development, assessing the extent, impact and effects of IUU fishing, addressing issues relating to capacity, accommodating new entrants, taking trade-related measures including catch certification and documentation.

So the question might be changed from “why is fisheries management successful (or not)”, since tuna management has not yet appeared to result in unsustainable or overexploited fisheries. Instead, the question might be “how can management be improved or further developed to ensure continued sustainability of tuna?”

3.2 Factors impeding optimum tuna management by RFBs

Some factors impeding the achievement of optimum tuna management have been identified by RFBs, and discussed above. These include:

Internal/Institutional

lack of mandate under establishing instrument;

lack of support, political will by some members with a conflict of interest;

need for strengthened and continuing programmes for scientific advice, research, stock assessments;

need for timely statistics, information collection/distribution;

need for financial resources to execute mandate;

need for capacity building/financial support for administrations in member States;

membership or cooperation by all fishing and coastal States.

External

IUU fishing, including failure to report by members and non-members;

increasing capacity of the fishing fleets.

3.3 Lessons learned from implementation of fishery management

As noted above, the sustainability of the tuna fishery may be unrelated to management efforts in some areas. A key feature of successful management in the western central Pacific region has been the coordination of coastal States through the FFA Secretariat, resulting in the harmonization of management principles and measures, together with a regional MCS/VMS programme. The technical backup of the SPC and development of information bases have also contributed to positive results.

In other regions, efforts by RFBs to implement the post-UNCED fishery instruments has yielded positive results and provided a suite of common denominators (and not necessarily the lowest ones!) for tuna management. Although ecosystem and precautionary approaches are still in early stages of development, new registers and information bases are being set up and new working groups being established to deal with current issues, the steps being taken are reasonably strong in the face of the difficulties expressed in section 3.2 and elsewhere in this paper.

4. HOW CAN THE DIFFICULTIES AND OBSTACLES BE OVERCOME?

As noted above, tuna fisheries are largely sustainable only partly because of management. Difficulties and obstacles - or challenges - for tuna fisheries may be anticipated in future, however. These would build on the current challenges, but should not be considered without reference to projections for global markets, marketing and technological developments (both for fishers and fisheries managers/enforcement). Although the latter is beyond the scope of this paper, Workshop participants are invited to take into account any such factors in considering challenges and obstacles to be overcome.

A starting point is that existing instruments are adequate to manage tuna fisheries. RFBs and States are only in early stages of implementing many of the requirements and concepts, and would need several more years to develop them properly.

The next step is recognition of the fact that tuna are highly migratory, and cooperation is needed to manage them throughout their range. This should not compromise coastal State sovereign rights, but should promote healthy coordination and reasonably consistent management through regional fishery bodies to the extent possible. The way forward would be to work on national and regional levels. First to promote further development of tuna management plans and ensure appropriate legislative and administrative frameworks are in place at national level, and strengthen RFBs wherever possible to address the constraints identified above. FAO is promoting the latter through a range of projects, including coordinating the third meeting of regional fishery bodies in Rome, 3-4 March 2003.

The solutions identified in the Bangkok Workshop could be applicable to tuna fisheries managed by RFBs as well as to coastal or fishing States as follows.

Development of allocation of rights will be an issue in future tuna management for some RFBs. Much attention has already been given to this issue (e.g. in the preparatory stages of establishing the WCPFC), especially in the context of rights-based fishing, “real interest”, past fishing patterns, contribution to research and other factors. This will be receiving further attention;

many RFBs are striving for transparency to the extent possible. As noted above, many non-members are being invited to participate in the work of RFBs;

participatory management may be more difficult to achieve in the context of RFBs, as fishers would be liaising with their national State;

precautionary and ecosystem approaches have been adopted by some RFBs, and any successes could be exemplary for other RFBs or States;

capacity building for RFBs and national administrations is important for successful management, and is acknowledged by tuna RFBs, noted above.

public awareness building is undertaken by some RFBs, and could prove to be useful precedent for others;

market incentives for tuna fisheries are less important than disincentives to market IUU caught fish. To this end, further development of trade, documentation and certification schemes could be useful.

Otherwise, factors impeding optimum tuna management noted in section 3.2 above should be considered with a view to overcoming the impediments described, mindful of ongoing activities of the RFB and FAO in that regard.

ANNEX 1

SUMMARY INFORMATION ON REGIONAL TUNA FISHERY BODIES

|

Body |

Establishment |

Headquarters |

Membership |

Area of Competence |

Main Functions |

|||

|

IATTC |

1949 |

La Jolla, California, USA |

Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador France, Guatemala, Japan, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Peru, USA, Vanuatu and Venezuela. |

Eastern Pacific Ocean |

To gather and interpret information on tuna; to conduct scientific investigation; to recommend proposals for joint action for conservation. |

|||

|

ICCAT |

1966 |

Madrid, Spain |

Algeria, Angola, Barbados, Brazil, Canada, Cape Verde, China, Côte d'Ivoire, Croatia, Equatorial Guinea, European Community, France (St. Pierre and Miquelon), Gabon, Ghana, Guinea Conakry, Honduras, Japan, Korea (Rep. of), Libya, Mexico, Morocco, Namibia, Panama, Russia, Sao Tomé and Principe, South Africa, Trinidad and Tobago, Tunisia, United Kingdom (Overseas Territories), United States, Uruguay, and Venezuela. |

Atlantic Ocean including the adjacent seas |

To study the population of tuna and tuna-like fishes; to make recommendations designed to maintain these populations at levels permitting maximum sustainable catch. |

|||

|

FFA |

1979 |

Honiara, Solomon Islands |

Australia, Cook Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, Fiji, Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Nauru, New Zealand, Niue, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, Tokelau, Tonga, Tuvalu, Vanuatu, Western Samoa. |

South Pacific (Central and West) |

To harmonize fishery management policies; to facilitate cooperation in surveillance and enforcement, processing, marketing and relations with third countries; to arrange for reciprocal access by member countries to their respective 200-mile zones. |

|||

|

WIOTO |

1991 |

Mahé, Seychelles |

Seychelles, Mauritius, Comoros, India |

Western Indian Ocean |

To harmonize policies with respect to fisheries; to determine relations with distant water fishing nations; to establish mechanism for fisheries surveillance and enforcement; to cooperate for fisheries development; and to coordinate access to EEZs of the members. |

|||

|

IOTC

Indian Ocean Tuna Commission |

1993

International Agreement under aegis of FAO (Article XIV of FAO Constitution) |

Victoria, Seychelles

|

Australia, People’s Republic of China, Comoros, Eritrea,

EC, France, India, Iran, Japan, Korea, Republic of, Madagascar, Malaysia,

Mauritius, Oman, Pakistan, Seychelles, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Thailand, United

Kingdom

|

Indian Ocean and adjacent seas north of the Antarctic

Convergence

|

To promote cooperation in the conservation of tuna and

tuna-like species and also promote their optimum utilization, and the

sustainable development of the fisheries.

|

|||

|

CCSBT |

1994 |

Canberra, Australia |

Australia, Japan, New Zealand |

Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans where SBT are found |

To collect, analyse, and interpret scientific and other relevant information on SBT, to adopt conservation and management measures including the total allowable catch and its allocation among the Members. |

|||

|

WCPFC |

2000 (signed, not yet in force at time of writing) |

(not yet established at time of writing) |

Signatories: Australia, Canada, China, Cook Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, France, Fiji Islands, Indonesia, Japan, Kiribati, Marshall Islands, New Caledonia, New Zealand, Nauru, Niue, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Philippines, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tonga, Tuvalu, United Kingdom (Pitcairn Island), United States of America, Vanuatu and Wallis and Futuna |

Boundaries south and east, area to cover range of tuna stocks |

inter alia: determine the total allowable catch or total level of fishing effort within the Convention Area for such highly migratory fish stocks as the Commission may decide and adopt such other conservation and management measures and recommendations as may be necessary to ensure the long-term sustainability of such stocks; (b) promote cooperation and coordination between members of the Commission to ensure compatible conservation and management measures; (c) adopt, where necessary, conservation and management measures and recommendations for non-target species and species dependent on or associated with the target stocks, with a view to maintaining or restoring populations of such species above levels at which their reproduction may become seriously threatened. |

|||

|

TECHNICAL BODY |

||||||||

|

SPC |

1948 |

Noumea, New Caledonia |

American Samoa, Australia, Cook Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, Fiji, France, French Polynesia, Guam, Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Nauru, New Caledonia, New Zealand, Niue, Northern Mariana Islands, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Pitcarin Islands, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tokclau, Tonga, Tuvalu, United Kindgom, United States, Vanuatu, Wallis and Futuna |

South Pacific South of the Equator |

To provide a regional service which provides information, advice and direct assistance to the Pacific Community through SPC member governments, either individually or collectively, in using living marine resources in the most productive and responsible manner possible, in particular through fisheries stock assessment, marine ecosystem research, small-scale tuna fisheries development support, coastal fisheries management support and fisheries information and databases throughout the area of competence. |

|||

ANNEX 2

REGIONAL TUNA BODIES RESPONSES

INDICATIVE ISSUES IMPORTANT TO REGIONAL FISHERY BODIES

A range of issues and challenges have faced RFBs in recent years, including those relating to effective governance by the RFB and to the conservation and management of the resource. The Secretariats of the RFBs were requested to indicate the five most important issues for them, and the reasons why they are important. Some RFBs indicated more than five issues, and some indicated less. If an RFB did not indicate an issue as a priority, this does not necessarily mean the issue is unimportant for the RFB. A summary of the priority issues and reasons identified by the Secretariats is in Part I.

The identification of priority issues is indicative only, since member countries have not formally reviewed the information, and mandates of RFBs are diverse. Many of the areas identified are overlapping, and for this reason issues important to some RFBs were not designated. This may not be clear from the categories identified by RFBs. However, taken together they show the general trends at the time of writing and may assist in reaching a clearer understanding of the challenges facing RFBs.

|

ISSUES |

IOTC |

FFA |

IATTC |

SPC |

CCSBT |

|

1. Implementing responsible fisheries management |

|

|

|

|

|

|

2. Ecosystem approach to fisheries management |

|

|

|

|

|

|

3. By-catch |

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. IUU Fishing |

|

|

|

|

|

|

5. Application of the precautionary approach |

|

|

|

|

|

|

6. Conflicts of interest at national level |

|

|

|

|

|

|

7. Increasing fishing capacity of the fleets |

|

|

|

|

|

|

8. Managing conflicts between artisanal and industrial fisheries |

|

|

|

|

|

|

9. Sound scientific advice, research, stock assessments, ecosystems,[82] etc. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

10. Statistical database; need for timely statistics, information collection/distribution |

|

|

|

|

|

|

11. Decline, restoration, recovery and conservation of certain fish stocks |

|

|

|

|

|

|

12. Need for a Scientific Research Programme |

|

|

|

|

|

|

13. Strengthening cooperation/coordination internally, with other RFBs and bodies |

|

|

|

|

|

|

14. Need for financial resources to execute mandate |

|

|

|

|

|

|

15. Method of determining financial contributions |

|

|

|

|

|

|

16. Need for capacity building/financial support for administrations in member States |

|

|

|

|

|

|

17. Human resource development |

|

|

|

|

|

|

18. Information exchange among member States, to decisionmakers and the public |

|

|

|

|

|

|

19. Membership |

|

|

|

|

|

|

20. Negotiation of a new Convention |

|

|

|

|

|

|

21. Establishment of the Western and Central Pacific Tuna Commission |

|

|

|

|

|

|

22. Aquaculture development |

|

|

|

|

|

|

23. Tuna industry development |

|

|

|

|

|

|

24. Change in balance between subsistence/commercial fisheries |

|

|

|

|

|

ANNEX 3

REGIONAL TUNA BODIES RESPONSES

IMPLEMENTATION OF POST-UNCED INTERNATIONAL FISHERIES INSTRUMENTS

Respondents were requested to provide information regarding recent activities, priorities or plans to implement the post-UNCED fishery instruments. Shaded cells indicate where a response was received and further details, as available, are in the text relating to each RFB.

Where RFBs indicated that the instruments in general are not relevant to their work this is indicated in a footnote. Where they have indicated specific instruments are not relevant, this is included in the text relating to each RFB. In some cases, where RFBs do not have a mandate to implement the instruments, reported action taken consistent with the instruments is indicated by shaded cells.

RFBs that did not respond are not included in the Table.

|

|

1993 FAO Compliance Agreement |

1995 UN Fish Stocks Agreement |

1995 FAO Code of Conduct for Responsible Fishing |

IPOA on Reducing the Incidental Catch of Seabirds in Longline Fisheries |

IPOA on the Conservation and Management of Sharks |

IPOA on the Management of Fishing Capacity |

IPOA on the Prevention, Deterrence and Elimination of IUU Fishing |

|

ATLANTIC OCEAN AND ADJACENT SEAS |

|||||||

|

ICCAT[83] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

INDIAN OCEAN AND INDO-PACIFIC AREA |

|||||||

|

IOTC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

PACIFIC OCEAN |

|||||||

|

FFA[84] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

IATTC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

SPC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

TRANS-OCEAN |

|||||||

|

CCSBT |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ANNEX 4

REGIONAL TUNA BODIES RESPONSES

ADDRESSING SPECIFIC ISSUES

Respondents were requested to indicate if their RFB has recently undertaken any activity, priorities or plans in relation to the following issues. Shaded areas indicate an affirmative response, and further details, as available, are in the text relating to each RFB.

Where RFBs indicated that the issues are not generally relevant to their work this is indicated in a footnote. Some RFBs indicated that some issues are not relevant, and this is included in the text relating to each RFB.

RFBs that did not respond are not included in the Table.

|

|

Implementation of precautionary approach |

Addressing ecosystem based fisheries management |

Assessment of extent, impact, effects of IUU fishing in area of competence |

Strengthening RFB’s capacity to deal more effectively with conservation, management issues |

Addressing issues relating to capacity |

Accommodating new entrants |

Catch certification and documentation |

|

ATLANTIC OCEAN AND ADJACENT SEAS |

|||||||

|

ICCAT[85] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

INDIAN OCEAN AND INDO-PACIFIC AREA |

|||||||

|

IOTC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

PACIFIC OCEAN |

|||||||

|

FFA[86] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

IATTC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

SPC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

TRANS-OCEAN |

|||||||

|

CCSBT |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| [37] The views expressed

in this paper are solely those of the author, Judith Swan, consultant, [email protected],