Conserving land and water creates wealth for 40 000 programme participants

In drought-prone, semi-arid central Tunisia, small-scale agriculture is based on the cultivation of olives and cereal. Farmers participating in the programme are building thousands of barriers, basins and terraces to catch rain runoff before it is lost down gullies and river beds. In candid interviews, they describe hard lives in a harsh landscape and frequent economic migration to the cities. But they also report how they have gained new hope through credit, training in improved farming methods and the construction of much-needed rural infrastructure.

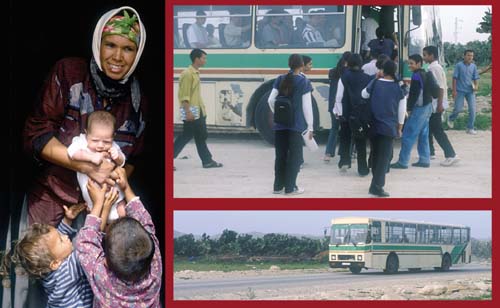

The poorest members of society, like this herder in Kairouan province, have been pushed onto the most marginal land. But such land still has potential for development.

"The boys would come back if there were a way to make a living here"

Mbarka Rahmouni

Farmer

In Tunisia's dry heartland, thousands of farm families are upgrading their lands, bringing more land under production and learning how to increase their yields. By the end of the Water and Soil Conservation Programme in 2005, 40 000 people will have improved their farms and standards of living.

In Kairouan, Siliana and Zaghouan, the three provinces with the highest percentage of rural residents and largest areas of degraded land in the country, thousands of barriers, basins and terraces are being built to stop erosion and channel rainwater towards the base of precious olive trees.

Planting olive trees

"It wasn't going well with cereal on this hill; the soil was no good," observed Moez Massoussi, a young farmer, pointing to a badly eroded hillside. "We saw that the neighbours did well with olives, so we decided to try."

His uncle and neighbour Hamadi Massoussi harvested four tonnes of olives in 2002 from 350 trees. He is doing well: farmers need 300 trees to support a family.

"Absolutely, it's clear the olive trees hold the runoff much better than cereal," he said. "We get lots of benefits from olive trees, too. The cuttings are fed to the animals and the wood is used for fuel."

Programme and farmer divide the costs of converting to olive cultivation: fertilizer, cost of digging planting holes and water channels, planting and irrigation, which cost 1.50 dinars (US$ 1.20) per tree, is paid by the farmer; each seedling, worth the same amount, is provided by the programme.

Precious water

Seasonal water courses - called oued in Arabic - are a prominent feature of drylands. When infrequent rain falls in the highlands, water sweeps down the oueds, which are baked rock-hard by the sun, and disappears into the sand or the sea. In the community of Oued Salah, Siliana, the programme, in consultation with local people and supported by regional services, have built a dam to trap the water. Farmers use mobile cisterns drawn by donkeys to transport water from the reservoir to the orchards flourishing on the surrounding hills.

Mbarka Rahmouni, an olive farmer in Oued Salah, hopes her husband and two eldest sons, who hold manual jobs in Tunis, the capital, and the coastal resort of Sousse, will one day be able to return and make a decent living off the land.

Programme participants build a stone barrier to block rain runoff, allowing it to sink into the soil instead of escaping.

"The boys would come back if there were a way to make a living here," she explained. "It's my dream that the men come home. It would be good for the younger children if their father were here to keep them in line."

Ms Rahmouni has learned how to improve her orchards. "We learned how to prune the trees so the sun penetrates the outer branches. You should see the flowering this year! We can see that it works."

Farm women carry water to their homes from a spring at the bottom of a ravine.

Country to city and back

Mokthar and Salha Hamzaoui struggled to earn a living from five hectares of arid hill country in Kairouan province. In 2002, they gave up hope. They bricked up their modest house, abandoned the land of their ancestors and moved to the city. Life was even worse.

The programme paid for installation of running water in many rural locations.

"It was hard in the city. I couldn't work with my husband. It was very expensive compared to here," said Ms Hamzaoui. "Then there were changes here."

In response to the announcement that the programme would build a 13-kilometre all-weather road into the district and assist farm improvements, the family moved back home. "Lack of access had been a big issue," Ms Hamzaoui explained. "I was worried about how the children would ever get to school. Now there is a new road.

"Everyone wants the best for their children," she said with a smile. "We hope the harvests yield enough for their education, that we plant more trees, produce more and do better."

Mr Hamzaoui depends on only 5 sheep and 58 olive trees to support his family, but he is improving his olive yield by grafting better varieties onto his trees and building basins around the trunks to catch runoff.

"I am working on my olive trees, building basins for them, for which I received credit and advice from the programme. Sometimes I still must go away to work in construction to earn extra money," he said.

A more prosperous sheep and olive farmer like Ali Ouslatti, Kairouan province, also gains from the programme: a 4 500-dinar (US$ 3 600) reinforced concrete water cistern catches the rain that falls on his property. He paid 10 percent of the cost, the programme paid 65 percent and the government 25 percent.

Thanks to his new basins and livestock - he spreads manure at the base of his olive trees - his trees are thriving, with a 30 percent increase in yield.

"Before, we didn't give any importance to individual basins," he said. "Now we see there is a big difference between an olive tree worked with a basin and one without." He added that he was proud to reintroduce the basins, which traditionally existed in many areas of Tunisia.

"I was worried about how the children would ever get to school. Now there

is a new road."

Salha Hamzaoui

Farmer

Plugging in

One of the poorest areas of Kairouan lies at the end of an uneven dirt track. Barren land somehow supports families and their herds of sheep. Hassen and Aicha Raisi have nine children and a tenth on the way. The children have a 12-kilometre walk to school along a rough path. Water is scooped from a spring at the bottom of a ravine.

To this desolate area, the programme brought a remarkable commodity - electricity - to 52 families, at the cost of 2 600 dinars (US$ 2 100) per family.

"It is a priority, because I grew up without it, and it was hard to do my homework," said Mr Raisi.

The district also enjoys its new water points, which serve 227 families, at the cost of 830 dinars (US$ 667) per family.

While Tunisia has made impressive strides against poverty over the past three decades - only 7 percent of the population today lives in poverty compared to 22 percent in 1975 - the weakest and poorest members of society have ended up on the most marginal land. Through the energy of the Tunisian Government and people, the generosity of Italy and the technical assistance of FAO, progress is being made against this last pocket of hardship.