By

Tom Brabben (HR Wallingford Ltd,

UK)

and

Gez Cornish (HR Wallingford Ltd, UK)

INTRODUCTION

An IPTRID mission to Zambia was undertaken in early May 2004 to review and assess the current levels of capacity development in Zambia. The three-person team assessed the status of capacity for agricultural water management, with a particular focus on existing irrigation planning, operation and maintenance functions. This included the support services provided by the Government, private sector and civil society. The objective was to identify priority areas for capacity development investments and to propose a strategic work plan for in-depth organizational and institutional capacity needs assessment.

Zambia has the potential, in terms of water availability (internal renewable freshwater resources), for greater development of water for agriculture. This overall potential and the recent development by the Government of Zambia, with the assistance of the FAO, of a draft irrigation policy led to early inclusion of Zambia in this IPTRID assessment. Earlier rapid appraisals by IPTRID in 1999 and 2002 had identified the potential for smallholder and emerging-farmers to adopt appropriate irrigation provided there was sufficient support from Government and market opportunities.

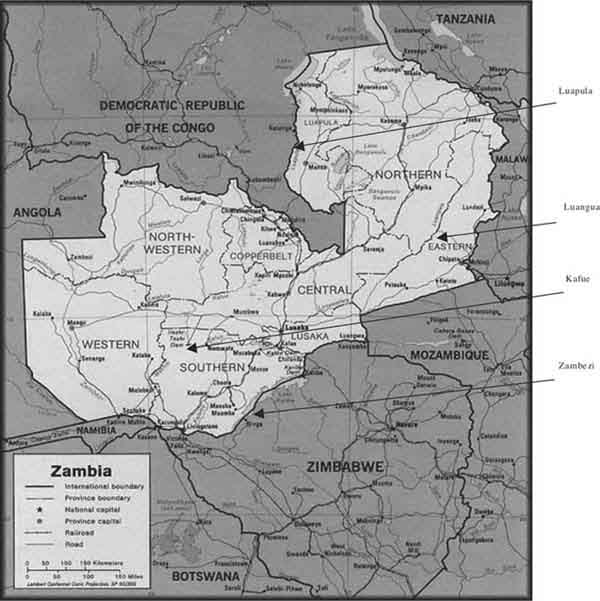

Informal irrigation is mostly found within the ‘line-of-rail’ corridor between Livingstone to Lusaka and on to the Copper Belt. (See Figure 4.1).

|

Zambian irrigation The Zambian irrigation sector is composed of traditional, subsistence oriented small holders and a relatively small and technologically advanced sector comprising large, medium-scale farmers and private companies producing predominantly for the local and international markets. In between is an increasing group of individual farmers (Emergent) who constitute approximately 20 percent of farm households. The type of crops currently under irrigation include food staples (wheat, rice, green maize, soya, paprika, sugar, tea, coffee) and horticultural crops (cabbage, tomatoes, onions, field beans, citrus, cut flowers and other high value horticulture). Zambia Irrigation Policy and Strategy: (DRAFT) January 2004 |

According to FAO[1] about 150 000 ha of land is under some level of controlled water management. The total land area of Zambia is 75.26 million ha of which about 21 percent (16.3 million ha) is potentially cultivable and about 1 million ha is actually cultivated.

The Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives (MACO) estimates the total area under controlled irrigation to be about 100 000 ha. This consists of a mixture of traditional, emerging and fully commercial farmers. Medium to large-scale irrigation covers about 52 000 ha while 48 000 ha are under informal or micro irrigation. If lowland seepage zones and wetlands with some degree of water management are included, this estimate expands to a total area under irrigation of approximately 156 000 ha. The Zambia Irrigation Policy Review and Strategy recognizes that this inventory needs updating through a controlled survey.

FIGURE 4.1 Map of Zambia showing rivers and ‘line-of-rail’

In 2001, MACO’s predecessor, the Ministry of Agriculture Food and Fisheries (MAFF) estimated that the irrigation potential in Zambia was about 200 000 ha[2]. This estimate was purely technical and made no reference to market linkages. It is considerably lower than the earlier estimate of potential - 520 000 ha reported by FAO in 1995[3].

In the past, international funding agencies and donors worked with Governments to enhance national capacity in the agricultural sector through a mixture of: promotion of policy reform - elimination of subsidies and price liberalization; building national policy-making capacity - training and awareness creation; and building capacity for extension and research - establishing facilities, training and education.

From the viewpoint of agricultural water management in Zambia, the results of interventions in these fields have been mixed. A small cadre of skilled and experienced individuals is spread between government service, the private sector and the NGO community. However, within the principal ministries, the lack of resources and funding for basic facilities limits the effectiveness of these individuals. The present freeze on recruitment, and limited funds for research and training, has resulted in a declining research programme and barely functioning extension service. These shortcomings have been partially overcome by the transfer of research and development services to trusts, cooperatives and to the private sector. International NGOs are working successfully with Zambian organizations to do the job of the extension service in promoting small-scale irrigated agriculture in specific areas of the country. However, the team felt that implementation of any new irrigation policy or initiative would be hindered by the lack of capacity among the various governmental stakeholders.

DEFINITION OF CAPACITY DEVELOPMENT[4]

Capacity is defined as the ability of individuals and organizations to perform effectively, efficiently and in a sustainable manner. Capacity development, at its broadest level, is the equipping of people and institutions to enable a country to achieve its development goals. Capacity development is an ongoing process to increase the abilities of individuals, groups, organizations and societies to perform core functions, solve problems, define and achieve objectives and understand and deal with their development needs in a sustainable manner.

IDENTIFYING STAKEHOLDERS AND CAPACITY NEEDS

It is difficult to pretend that the team used or developed anything more sophisticated than a common sense approach to identifying and understanding the roles of the different institutions involved in the agricultural water management sector. So far, we have examined the present status and proposed some solutions that are specific to the problems presented to us. The approach used could be considered typical for early project identification and scoping stage.

Elements include the following:

It was clear to the team that pre-mission planning and engagement of the national stakeholders at an early stage is important and crucial. Buy-in of national stakeholders and decision-makers to the objectives of the mission is necessary if confusion is to be avoided about what is meant by capacity building and what could be expected from an assessment of capacity needs. Fundamental questions about capacity building, what it means and what it leads onto, have to be anticipated and addressed early on in a mission and preferably before it starts.

Identifying the stakeholders

Three broad groups of stakeholders were considered:

In Zambia, basic enquiry and reference to existing published reports readily identified the stakeholders listed in Annex 4.1, Table 4.1. This is not an exhaustive list but it demonstrates the wide variety and large number of institutions having a role in Zambia’s overall capacity to develop the irrigated agricultural sector. It should be borne in mind that this is a country with a very small and relatively under-developed irrigation sector - the list of stakeholders might be much longer in countries with a better-developed irrigation sector.

|

Definition of a stakeholder ‘Any group within or outside an organization that has a direct or indirect stake in the organization’s performance or its evaluation. Stakeholders can be people who conduct, participate in, fund, or manage a programme, or who may otherwise affect or be affected by decisions about the programme or the evaluation.’ Horton et al., 2003 |

Identification of stakeholders is relatively easy, however, assessing the degree of commitment and ‘buy-in’ to the objectives of the mission and to the overall concept of capacity development is less clear.

Another way to look at stakeholder involvement is to examine who might be interested in or affected by a capacity assessment exercise. Table 4.2 (see Annex 4.1) was prepared after the mission and poses the following questions to the stakeholders who were identified in Table 4.1:

Using these standard questions provides a means of identifying the relative importance of different stakeholders and their place in subsequent, more detailed definition of options for capacity development.

Government Policy - is it clear?

A draft Zambian Irrigation Policy and Strategy was released for discussion in February 2004. The driving force for the development of a policy and strategy is the need ‘to shed the dependence on the volatile production from rainfed systems and ensure food security.’

The strategy sets out four strategic paths (see list below) each with a specific impact on the three types of player in the irrigated sub-sector, commercial farmers, emerging farmers and traditional farmers, viz:

The strategic aim of this draft policy is to expand the emerging farmer[6] base in Zambia by promoting the building of commercial irrigation enterprises based on the experience of the large-scale commercial sector. It should be noted that, at present, emerging farmers are not numerous. Much of the successful implementation of the policy will depend upon correct identification of market opportunities at local, national and regional levels. The draft document rightly cautions against expecting publicly funded irrigation to solve the country’s problems related to food security and poverty. Much can be achieved more quickly and cheaply with respect to rainfed production before irrigation becomes an obvious next step. The conclusion is that irrigation has a role but needs to be integrated into a wider water resource and agricultural review.

|

Real opportunities Recent droughts, conflict and politico-economic meltdown in the Zambian ‘neighbourhood’ have opened new internal and regional markets. [There is] a significant opportunity for a reinvigorated and expanded irrigation sector in Zambia. In comparison to the neighbouring state of Zimbabwe, Zambia would appear to have under-utilized its huge irrigation potential. Since the effective demand in the local market is relatively small and is unlikely to absorb the increased agricultural production arising from new irrigation development, export markets need to be developed if Zambia is to realize its comparative advantage in export grade produce. Zambia Irrigation Policy and Strategy, DRAFT, January 2004 |

The level of government commitment to an irrigation policy is clear. What is unclear is whether this particular draft will be the policy that will be finally adopted. MACO, with the assistance of FAO, was instrumental in developing the draft policy document. However, some stakeholders feel that the consultation process did not permit the effective participation of other water interest groups in the country.

Similarly, the near complete Water Resources Action Programme implemented by the Ministry of Energy and Water Development (MEWD) makes little mention of the need to integrate agricultural water use into the plan. In the case of water supply and sanitation, there are rivalries between the energy and water interests and local government who are responsible for water supply and sanitation service delivery. The conclusion is that there is an urgent need to place irrigation into a fully integrated water resources strategy for the country, which in turn requires greater integration, communication and cooperation between ministries.

The present recruitment freeze in the government service, and lack of investment for education/training in appropriate technical skills, raises the concern that effective implementation of the policy will be hampered.

At the highest level, Government is committed to irrigation, as demonstrated in the setting up of the President’s Irrigation Task Force[7] in January 2004. The Task Force has a specific mandate to secure new money for irrigation investment, with a target of US$13.7 million. However, the Task Force is not addressing the mechanisms through which such new investment will be accessed and used.

Capacity of the different institutions and organizations

The team assessed the capacity of the different organizations/stakeholders. This assessment was limited in scope because of the time available. Normally the more rigorous framework of a SWOT analysis would be used. A sample of the different institutions is presented here to indicate the scale of present needs.

Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives (MACO) has a mandate but no financial resources and few people. Particular issues related to capacity needs are:

lack of resources (human, financial and physical) to run MACO to satisfy its mandate;

unclear role of MACO in the overall development process;

human resource development plans are unrealistic during the present freeze in recruitment leading to confused career development and highly fragmented and distorted salary and compensation system;

resistance from within MACO to structural change, probably a result of fears concerning a possible loss of prestige, influence and power of individuals;

poor alignment of agricultural research agenda to strategic goals;

absence of a vision of a phased and focused development approach in which the technical, financial and social aspects of irrigation are addressed adequately and services provided to the farmers through direct contact, sensitization, demonstration, farmer group formation and training; and

lacking integration of the irrigation policy within the National Water Act.

MACO is also responsible for the Extension Service. This service is effectively defunct because of chronic and long-term lack of funds. An extension service is the conventional/traditional mainstay of support and development to the agricultural sector. Most farmers spoken to had little or no contact with Camp Officers (Extension Officers) and were not confident that the present service could assist them. Efforts to train camp officers and farmers through initiatives such as farmer field schools have been limited due to a lack of resources.

In the face of this reality, commercial farmers, producer organizations and cooperatives now buy-in or provide their own extension services and advisers. At the level of smallholders, the NGOs such as IDE Zambia and CLUSA provide agronomic and marketing information to ensure their projects are successful. While the technical support provided by the NGOs is good, it is restricted in its range to the specific areas where the NGO is active and will only be sustained for the duration of a project.

National Irrigation Research Station (NIRS), Mazabuka is sited within the principal irrigation area of the Kafue and had a good reputation in irrigated agronomy, testing of crops and in making well-founded recommendations on surface irrigation. That was in the past, now the particular issues are:

Golden Valley Agricultural Research Trust (GART) promotes sustainable agriculture by undertaking applied research studies mainly related to livestock and rainfed field crops. The Trust model is a way of freeing the organization from Government and providing more autonomy to raise funds to do applied research commissioned by its governing board or by clients (including private sector and donors). The team found:

The Trust model may be one way to organize applied research to support irrigation policy.

The private sector is seen as offering a variety of models for capacity development that could be followed. Though not seen, both Agriflora and York Farms produce high value/low volume horticultural products for export and have developed small-scale and outgrower schemes. They provide agronomic advice to their growers through in-house teams. The Kaleya Smallholders Company Ltd, Mazabuka, is a cooperative focussing on sugar. A small, professional management team is employed by the cooperative to run the scheme on a commercial basis. The good results are a result of long-term commitment to training and support. Outgrower schemes and cooperatives are fashionable. While not numerous in Zambia they appear to provide a sustainable source of employment and income. Immediate shortcomings in technical skills to irrigate and run the enterprises upon commercial lines are bought-in. Technologies and skills are transferred and, as was the case at Kaleya, the farmers have now become skilled and competent. There is a long waiting list to join the cooperative and an entry procedure that excludes those who do not show enough competence/dedication/hard-work. However, it should not be overlooked that the Kelaya model is the result of 20 years of evolution, established with five years of direct investment and support from the Commonwealth Development Corporation.

Equipment dealers are mostly based in Lusaka, servicing the commercial sector, importing equipment on demand. Some offer advisory and design services, as a means of securing business though the service is limited at present. As an example, Amiran has two irrigation design engineers to cover a country with a land area substantially larger than France.

There are several Producer Organizations offering marketing and business advice for ‘members’ or ‘subscribers’ for agricultural commodities such as paprika, coffee and sugar. They provide advice to growers, provide market information, encourage quality production and pest control and collectively promote the product.

The Zambian National Farmers Union (ZNFU) provides services on behalf of its members (that now include emergent farmers), produces responses to government on behalf of the farming community in general and campaigns on strategic issues of agricultural importance. The ZNFU is well regarded and viewed as a constructive partner by government.

As part of their programmes NGOs such as IDE Zambia and Total Land Care (TLC) Zambia offer farmer training and provide agronomic advice to traditional farmers. This development of the abilities and capacities of ‘client’ farmers has been successful and has furthered the objectives of their programmes.

Both IDE and TLC have filled the gap left by the non-existent extension service in the areas where they are working by using project funds. The lessons are clear: (a) extension services have an important role in assisting some of the poorer farmers to become emergent farmers and (b) extension service provision cannot be provided over the long term by the NGO community unless adequately funded.

Quasi-governmental organizations set up by the Government, but independent of the line ministries, are making an impact upon the development agenda. The Agricultural Consultative Forum (ACF) provides a facilitation role to bring the stakeholders and decision-makers together. The model seems to work well and could be a useful institutional model on which to base a similar, irrigation, forum.

CAPACITY - A CONSTRAINT TO IRRIGATION DEVELOPMENT?

Lack of capacity is a major constraint to the uptake of publicly funded irrigation in Zambia. One could go further and say that without adequate resources, skills, facilities and institutional arrangements it will be difficult to implement any development agenda whether it is for irrigation or not. The draft irrigation policy and strategy document suggests a mix of policy interventions and programmes including capacity building and recognizes that limited overall capacity to develop irrigation is a weakness of government institutions.

There is no clear link between the lack of capacity and the fact that irrigation hasn’t taken off in Zambia, despite the apparent potential in terms of soil and water resources. We suspect that irrigation has always been of marginal interest in the country and that agriculture has focussed on rainfed cropping and livestock. Irrigation has occupied certain niche positions, sugar production in the Kafue, vegetable and flower production near Lusaka.

There are other constraints to the development of a large irrigated agricultural sector beyond what is presently practised. These include:

lack of commercial credit, banks prefer to lend to the Government;

lack of transport infrastructure to allow access to markets - Zambia is land-locked and apart from along the ‘line-of-rail’ corridor has poor transport connections;

lack of suitable soils and water resources (where soils and available water combine favourably may not be the most suitable place for market access);

little perceived need for irrigation due to reliance on rainfed cropping (also recognizing that crop improvements may make better sense in the immediate future); and

over reliance (certainly in the past) on copper mining as the economic engine.

With respect to publicly funded irrigation the low number of trained and motivated staff at all levels in MACO is a problem. This could be overcome quite quickly by allowing recruitment at reasonable salary levels or by seconding staff from private enterprises into the Ministry. Training more people and fitting them into MACO (even if this was possible in the present freeze) would not necessarily guarantee greater uptake of irrigation by emerging farmers.

More critical perhaps is the capacity of MACO to formulate and prepare programmes and projects that can compete with other national priorities (education, governance, other agricultural priorities) and which will be attractive to donors and funding agencies. It will be necessary to generate a stream of projects and programmes, in line with the new policy, to fund capacity building activities and allow rational development of the irrigation sector.

POINT OF ENTRY

The choice of entry point for capacity assessment and then capacity development will depend upon existing institutions and the aims of the assessor. Various models or approaches can be adopted. In the case of Zambia, there are probably two entry points, at the policy and at the project level.

Policy level options

Support at the policy level would enhance national capacity to formulate a policy. In the case of Zambia, this has recently been completed. It is not immediately apparent whether this has resulted in a lasting improvement in capacity, as consultants undertook much of the work. It has already been noted that an irrigation and water resources management (IWRM) perspective will require greater cooperation between ministries and stakeholders. The need for genuine IWRM should be revisited at an early stage by involving principal players from the various ministries but this will require the overcoming of real and understandable ‘turf disputes’.

The establishment of a stakeholder forum for a genuine exchange of views would directly support future policy development and review by providing the appropriate forum. However, once again, internal political disputes and struggles for influence could hamper this approach.

The holistic approach would need to be coordinated. Creation of a programme/project planning group/unit could be another entry point. Ideally, this should be staffed from the relevant ministries with national secondees for particular skills and skill transfer. This unit could be donor funded to start with; however, it will be more sustainable if placed within the body charged with national planning and implementation of the poverty reduction strategy initiative (PRSP).

If the Government of the Republic of Zambia can be seen by the donor community to take a lead on this then there will be more interest in support programmes and projects that deal with the productive uses of water. Interaction with the donor community could follow the Ugandan model, where the Ministry of Finance takes the lead in organizing sector-wide reviews in collaboration with the donor community.

If implemented, the draft irrigation policy will entail some restructuring within the principal Ministry (MACO) and review of its mandate. This will need to be addressed from within government using external experts as appropriate to guide (build capacity) but again, concerns over defending ‘positions’ is likely to dominate this process.

Project level options

Continuing with the project approach is attractive, as this is the ‘entry point’ that most officials understand and look for. Project responsibilities often involve moving out of the Ministry for the duration of a project, giving greater autonomy, responsibility and contact with donors and international financial institutions (IFIs). Projects are likely to remain the main vehicle for funds to flow into irrigation. The challenge remains to formulate projects that deliver sustainable improvements in institutional capacity and are attractive to the relevant ministries. At present, the donor community may be more enthusiastic about capacity building than the agencies and institutions whose capacity they seek to enhance.

National and international NGO experience can reinvigorate extension-type services especially with respect to traditional and emerging farmers. The challenge in the long-term will be to create extension services that are insulated from the uncertainties of limited government funding.

The team’s conclusion is that the entry point for any overhaul of capacities to support and facilitate irrigation will have to be through existing government structures at the policy level. The project level will continue and should be organized to enhance rather than duplicate government policy.

CONCLUSIONS

The conclusions of this case study are based upon a short IPTRID mission to Zambia looking at capacity needs assessment in agricultural water management. The conclusions from this initial, scoping, mission are:

The perception of ‘capacity development’

Staff from ministries, NGOs and the private sector generally struggled to understand what a ‘capacity needs assessment mission’ offered them. In turn, it must be acknowledged that the mission team found it difficult to offer tangible examples of capacity development projects.

By its nature, this first mission was broad ranging, aiming to contact as many as possible with a stake in agricultural water management. Subsequent steps will need to prioritize needs and address the question, ‘Capacity for what?’

The priority of water resource management and allocation of resources

The formulation, in draft, of a national irrigation strategy signals government support towards the sector.

However:

The lack of financial and human resources to run the ministries in Zambia is a major constraint and will remain so, and

Government endorsement and implementation of the policy is still awaited.

IWRM has not taken hold. Ministries fail to talk to each other and don’t see water as a common resource. A mechanism is needed to overcome traditional independent sectoral thinking with respect to water. Developing awareness and aiding communication between ministries: MACO, MEWD, the Ministry of Local Government and Housing (MLGH) and stakeholders would be enhanced by a water forum, which should address the different issues and assist in setting priorities for irrigation within an overall water resources plan. The present Water Resources Action Plan, developed by the Ministry of Energy and Water Development, would have been the ideal mechanism to achieve this but it seems to have failed to recognize agriculture as a legitimate stakeholder.

IPTRID is now reviewing these mission conclusions and has proposed the following actions that could support the adoption of the proposed irrigation policy.

A possible next step could be to examine the capacity needs in more detail from the perspective of the water sector as a whole. This would require a longer mission that includes institutional specialists and greater national participation. The aim would be to prepare a full review of the research and extension service system, based upon a comprehensive assessment of priority needs in agricultural water management in Zambia. This will then provide input to the design of a revised research and extension service system, and

Secondly, promote the establishment of an irrigation consultative forum similar to the existing ACF but with a mandate restricted to issues related to agricultural water management. It would provide a forum for all water and agriculture sector stakeholders to become fully engaged in the development of an integrated agricultural water resource management approach in Zambia.

Outputs from such a mission would be focussed on providing information to create an irrigation-oriented body within the country. Such a body should have a strategic overview and ensure participation of relevant stakeholders. It would facilitate service delivery and have responsibility for planning and regulation of the sub-sector including the control of government investment programmes. Creation of such an ‘apex body’ is referred to in the draft policy document but is a contentious concept for many within the present ministry structure!

Much of what has been found in Zambia could equally apply in other African countries. With regard to a more generalized approach to capacity needs assessment we conclude that:

capacity development has to be for a purpose - ‘Capacity for what?’ - and done with the full collaboration and understanding of the national stakeholders;

buy-in from government is important if capacity development is to be accorded proper priority;

more needs to be done in explaining to government officials and stakeholders what ‘capacity needs assessment’ and ‘capacity development’ will do for them, their projects and their country; and

the idea that ‘capacity development rather than infrastructure should be the central focus of future irrigation development strategies’, which was the consensus of the Montpellier workshop in 2003, may not strike a chord in many African states where physical and institutional irrigation infrastructure has never been established.

|

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This paper has been prepared for IPTRID following a mission to Zambia in May 2004 under the leadership of Wilfried Hundertmark. The contribution to the mission by Gez Cornish and Tom Brabben of HR Wallingford Ltd was supported by DFID, UK. |

ANNEX 4.1

TABLE 4.1 Stakeholders for agricultural water management in Zambia

| Government ministries and agencies |

Agricultural sector trusts |

Private sector and producer organizations |

NGOs and civil society |

| Agricultural Consultative Forum (a forum for the entire agricultural sector and not only for agricultural water management) | |||

|

Ministries Ministry of Agriculture & Cooperatives Department of Field Services (Technical Services Branch) Ministry of Energy & Water Development Water Resources Action Programme Department of Water Affairs Water Development Board Ministry of Local Government and Housing Training and research centres University of Zambia Natural Resources Development College Mount Makulu Research Station, Chilanga. National Irrigation Research Station, Mazabuka |

Golden Valley Agricultural Research Trust | Private sector Agriflora York Farms Kaleya Smallholders Co. Producer organizations Zambia National Farmers Union Tobacco Association of Zambia Zambia Coffee Growers Association Cheetah Zambia (paprika growers) Equipment dealers Amiran Saro Agricultural engineering |

International Development Enterprises, Zambia Total LandCare Zambia CLUSA (not seen this time) PAM Programme Against Malnutrition (not seen this time) |

TABLE 4.2 Stakeholder roles and interests

| Stakeholder name |

Interest, position, function & official

mandate |

Reason for inclusion in capacity needs

assessment |

Possible future role in agricultural water

management |

| Ministries | |||

| MACO | Department of Field Services, Technical Services Branch responsible for the planning of irrigation. | Principal ‘client’ for improved capacity in sector if to remain responsible for leading irrigation strategy. | Fully active involvement |

| Ministry of Energy and Water Development (MEWD) | Responsible for water resources in the country. | Need to be involved if water for food production is to be integrated into the water strategy. | Limited but active involvement |

| Ministry of Local Government & Housing (MLGH) | Responsible through local administrations for water supply and sanitation services. | Useful experience of providing rural WatSan services. | Limited involvement |

| Training & research centres | |||

| University of Zambia | Formal training of agricultural and irrigation professionals. | Senior staff work closely with Ministries teaching courses that could be adapted to respond to irrigation policy. | Limited involvement at present |

| NRDC | Training of agricultural technicians, support staff. | Closer involvement with appropriate technology, small-scale farming and technician level capacity development needs. | Limited involvement at present |

| Mt. Makulu | National research centre for agriculture. | Responsible for overseeing Government programme of agricultural research and extension services. | Limited involvement |

| NIRS | National irrigation centre, testing equipment and crop suitability. | Principal research centre for irrigated agriculture despite being severely run-down. | Fully active involvement |

| Agriculture sector trusts (GART) | Possible example of how to implement applied research in sector. | Useful expertise and experience. | Limited involvement |

| Private sector | Variety of interests encompassing large enterprises through to cooperatives. | Provision of services, expertise. Main beneficiaries of improved CD. | Limited involvement/informal role |

| Producer organizations | Representing agricultural sector producers. | Represents the mix of views from the sector as a whole. | Limited involvement |

| Equipment dealers | Some interest in seeing increase demand for equipment and advisory services. | Expansion of business will depend upon the skills and abilities of irrigating farmers. | Limited involvement/informal role |

| NGOs & civil society | Wide range of interests mainly focussed on the level of informal small-scale, not directly handled by Government. | Close contact with rural communities and emerging farmers. | Fully active involvement |

| ACF | Forum for entire agricultural sector. | Represents a working model for sector wide consultation. | Limited involvement |

|

[1] Irrigation in Africa in

figures, FAO (1995). [2] Strategic Plan for Irrigation Development MAFF (2001). [3] Irrigation in Africa in figures, FAO (1995). [4] From: D. Horton, A. Alexaki, S. Bennett-Lartey, K.N. Brice, D. Campilan, F. Carden, J. de Souza Silva, L.T. Duong, I. Khadar, A. Maestrey Boza, I. Kayes Muniruzzaman, J. Perez, M. Somarriba Chang, R. Vernooy, and J. Watts. 2003. Evaluating capacity development: experiences from research and development organizations around the world. The Netherlands: International Service for National Agricultural Research (ISNAR); Canada: International Development Research Centre (IDRC), The Netherlands: ACP-EU Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation (CTA). [5] Seasonally waterlogged, predominantly grass-covered depressions often found in upper drainage basins. [6] May partially subsist from their own production, their principle objective is to produce a marketable surplus generally comprising horticultural crops. [7] Members are: President’s Economic Adviser; Deputy Governor, Bank of Zambia; Permanent Secretary, MACO; Executive Director, ZNFU; Secretary to the Treasury. |