A . D E W A G T A N D M . C O N N O L LY

There are 40 million people living with HIV/AIDS in the world , of whom 29.4 million are in Africa. The highest levels of HIV/ AIDS are found in southern Africa, with prevalence rates exceeding 30 percent among the adult population in Botswana, Lesotho, Swaziland and Zimbabwe (UNAIDS/WHO, 2002). There is an increase in the number of children in sub-Saharan countries who are affected by HIV/AIDS.

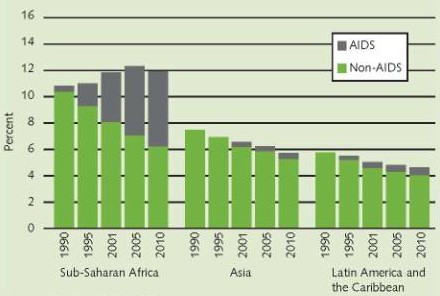

Among the more than 34 million orphaned children in Africa, 11 million became orphans as a result of AIDS. From 1990 to 2010, the number of orphans in sub-Saharan Africa who have lost both parents will triple because of AIDS. It is estimated that, by 2010, 5.8 percent of all children in the region will have been orphaned by AIDS. Figure 1 summarizes the increase in number of AIDS and non-AIDS orphans (UNAIDS/UNICEF/ USAID, 2002).

A wide variety of problems can affect orphans, including increased food insecurity, stigmatization and discrimi- nation, reduced access to education and economic opportunities, and sexual abuse and exploitation (Desmond, Michael and Grow, 2000; Donahue, 1998; Gilborn et al., 2001). Based on several studies, the following discussion explores issues such as the capacity of caregivers, education, food security, survival and nutrition among orphans in the context of the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

The vulnerability of children increases long before the death of a parent or guardian. Children watch their parent deteriorate and eventually die. They lose family and identity and are subject to increased malnutrition and reduced opportunity for education. Without adequate care and support, many are exposed to exploitative child labour and abuse and face increased vulnerability to HIV infection. When a mother dies, the level of care is reduced dramatically, and children become more susceptible to illness. It should be recognized that figures on the number of orphans in Africa show only a segment of all of the children who do not receive adequate parental care.

Percent of children under age 15 who are orphans, by year, region and cause, 1990–2010

Source: UNAIDS/UNICEF/USAID, 2002.

|

Orphans and vulnerability |

|

WHEN DEFINING THE vulnerability of a child, assessing if one or both parents are alive is not adequate. In many parts of Africa, it is common that children are fostered by relatives and do not live with their biological parents, even when the parents are alive. If children are living with other relatives and one or both of these relatives die, this will also have a large effect on the lives of the children (Foster and Williamson, 2000). Orphans can be grouped as maternal orphans, paternal orphans and double orphans. Children may also have an ill parent or an ill foster parent. Some children have lost both their parents and their foster parents. |

Lack of proper care for orphans is further exacerbated by the fact that many adults in the extended family who care for orphans are also HIV-positive or living with AIDS. The disease increases poverty in families as time and money are spent to care for an escalating number of sick relatives, and for treatment in cases in which people develop AIDS-related infections.

The resources and caring capacity of mothers, fathers and relatives vary, according to evidence regarding care for orphans. A study in Malawi, Zambia and Zimbabwe (SADC/FANR, 2003) showed that, on average, 20 percent of households were caring for one or more orphans. More often it was female-headed households rather than male-headed households that cared for orphans. In Malawi, almost 40 percent of female-headed households cared for orphans. In these three countries, fewer than 1 percent of all households were headed by children.

In areas where AIDS has weakened the extended family system and other relatives such as uncles and aunts are chronically ill or have died, it seems that grandparents are increasingly charged with the task of caring for orphans. In Zambia, 40 percent of households headed by an older person were caring for an orphan, while 28 percent of households headed by a younger adult were caring for such children (Foster and Williamson, 2000). In a study in Uganda, 40 percent of the adults who were looking after orphans were HIV-positive parents themselves (Gilborn et al., 2001).

When a parent becomes ill, the education of a child is disrupted. A study of data collected in Uganda (Gilborn et al., 2001) shows that 26 percent of children reported a decline in school attendance and 25 percent reported a decline in school performance when parents became ill. According to the children of this study, parental illness disrupts school attendance because children stay home to care for sick parents. They have increased household responsibilities and need to care for younger children. They suffer emotional distress that interferes with school, and they have less money for school expenses.

In another study of children in Uganda (Sengendo and Nambi, 1997), it was found that among children 15–19 years of age whose parents had died, only 29 percent had continued schooling undisrupted; 25 percent had lost school time, and 45 percent had dropped out of school. The school-age children with the greatest chance of continuing their education were those who lived with a surviving parent. Children fostered by grandparents had the least chance.

Large disparities in school attendance may exist between children who have lost both parents and children who have at least one living parent. Among the eight African countries for which there were data, school absenteeism among orphans was 9–44 percent higher than among non-orphans (UNICEF, 2003b).

The first large-scale manifestation of the combined impact of HIV/AIDS and food insecurity caused by severe drought was seen in the humanitarian crisis suffered in southern Africa in 2002. The following associations between HIV/AIDS and food security were found (SADC/FANR 2003):

Even in years with average food production, HIV/AIDS can reduce household food security and make children more vulnerable. A study in Kenya showed that the death of the male head of a household reduced the value of the household crop production by 68 percent (Yamano and Jayne, 2002). A study in Rwanda showed that when the father had died, 53 percent of the households had a less nutritious diet; when the mother had died, the figure was 23 percent (Donovan et al., 2003). When the father was ill, 42 percent of the households had a less nutritious diet; when the mother was ill, 34 percent of the households had a poorer diet. Data from Kagera, United Republic of Tanzania, show that, among the poorest 50 percent of households, expenditure on food was reduced by 32 percent, and food consumption by 25 percent (World Bank, 1997).

Depending on the seriousness of the situation and the coping capacity of the household, the different strategies that a household may employ to reduce food insecurity after an adult family member has died can be grouped as 1) reversible; 2) disposal of productive assets; or 3) destitution (see Table) (Donahue, 1998).

It should be expected that reduced financial resources and child care capacities would lead to greater vulnerability to morbidity and mortality for children affected by HIV/AIDS. However, data to support this hypothesis are relatively weak. A study conducted in the northwestern United Republic of Tanzania found that children whose mother alone had died had a 2.5-times higher risk of morbidity (Ainsworth and Semali, 2000). When the father alone had died, this risk was 1.8 times higher. In particular, children of poorer households were made more vulnerable by the death of a parent.

In order to show a link between being affected by HIV/AIDS and morbidity and mortality, large sample sizes would be needed. However, the most vulnerable children are those under two years of age, and the number of children who have lost one or both parents at that age is relatively small. This phenomenon could explain why few data are available on the links between morbidity and mortality and being affected by HIV/AIDS.

Several studies have found higher malnutrition rates among orphans. In the United Republic of Tanzania and Zambia, orphans were more likely to be stunted, but not more likely to be wasted, than non-orphans (Semali and Ainsworth, 1995; Poulter, 1997). Nutrition surveillance in Zimbabwe showed that underweight and stunting were higher among orphans than among non-orphans – 22 percent versus 17 percent, and 34 percent versus 26 percent, respectively (UNICEF, 2003a). Some studies have not shown that orphans were at an increased risk of malnutrition. A study carried out in Malawi showed that, among children living in villages, orphaned children were not more malnourished than non-orphans (Panpanich et al., 1999).

| Food insecurity coping mechanisms | ||

| REVERSIBLE | DISPOSAL OF PRODUCTIVE ASSETS | DESTITUTION |

|

Seeking relief from family members, friends and neighbours |

Using savings | Depending on charity |

| Reducing consumption |

Selling assets including land, animals, equipment and tools |

Breaking up the household |

|

Switching to low-labour food crop production (often less nutritious) |

Reducing spending on food, health | Migration |

| Switching from cash crops to food crops | Criminalization and prostitution | |

| Decreasing spending on education | ||

| Generating income | ||

Source: Adapted from Donahue, 1998.

Factors affecting children's survival, growth and development

| Nutrition and care capacity |

|

NUTRITIONAL STATUS IS the outcome of a combination of household food security, health service and provision of care. As financial resources in households affected by HIV/AIDS decline, access to health care is compromised. Caring capacity for children is affected by HIV/AIDS in the following ways:

|

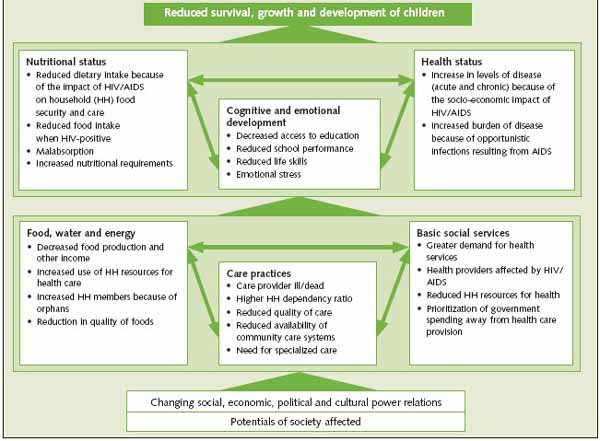

Orphans and other children living with families affected by HIV/AIDS are increasingly among the most vulnerable children in Africa. They are at a higher risk of food insecurity and malnutrition, as well as of dropping out of school, abandonment and homelessness. Figure 2 provides a causal framework showing immediate and underlying factors that affect the survival, growth and development of children.

The crisis that befell southern Africa in 2002 illustrated the severity and magnitude of the combined impact of HIV/AIDS and food insecurity. As the number of households affected by HIV/ AIDS continues to grow and the number of orphans increases, households and communities will be less able to cope with climatic, economic or political crises. As a result, the magnitude and severity of crises in the future are expected to increase.

Examples of, and linkages among, developmental and humanitarian interventions

The long-term impacts of HIV/ AIDS will ultimately include an erosion of traditional coping mechanisms and community safety nets. Much of the evidence described above shows that, even without acute food insecurity as a result of drought or other additional crises, the health, food security, nutritional status and cognitive development of children affected by HIV/AIDS are jeopardized.

An adequate response to the situation should have characteristics of both a developmental and a humanitarian response. A combined approach needs to be planned and implemented in such a manner that a humanitarian approach supports the recovery of capabilities and coping mechanisms of communities, households and families, and it should not lead to long-term dependency on larger communities. As the capability of communities, households and individuals is restored, developmental approaches should support the process of capacity development.

To date, the support to orphans and other children made vulnerable by HIV/ AIDS has had the characteristics of a traditional “development response”. The focus has been on building the capacities of families and communities to care for affected children with existing community resources.

More recently, some groups, in particular non-governmental organizations, have been providing a “humanitarian response”on a small scale. On a larger scale, such an approach was attempted for the first time in 2002 as part of the response to the crisis in southern Africa, where HIV-affected families were specifically targeted for food aid.

The protection of and support for the survival, growth and development of children affected by HIV/AIDS should come from the different sectors addressing these factors. The immediate and underlying factors that have an impact on children affected by HIV/AIDS are varied and interlinked (see Figure 2). An adequate response therefore requires a coordinated multisector response from different government ministries and departments with support from different non-governmental organizations and United Nations agencies.

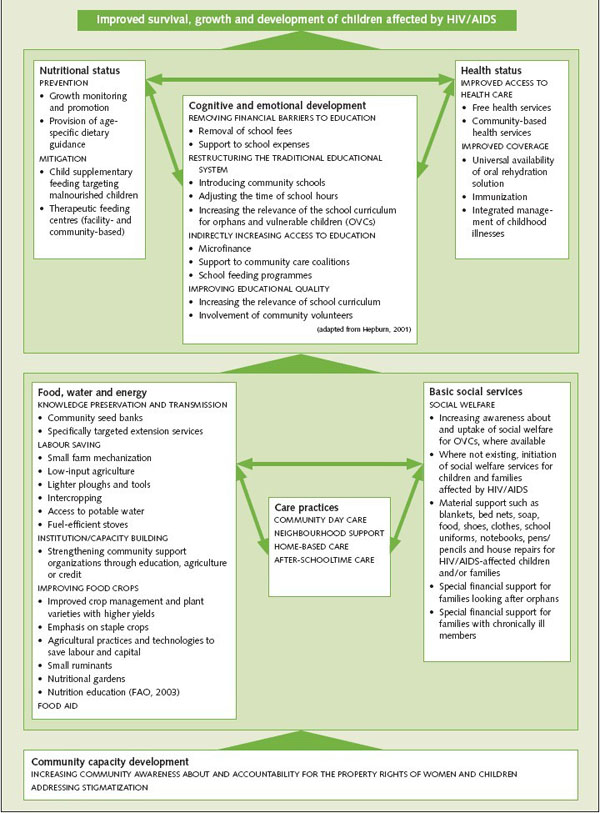

The education, agriculture, nutrition, social welfare and health sectors must strengthen their collaboration. Examples of developmental and humanitarian interventions from different sectors and how they can be linked are illustrated in Figure 3.

The aim should be to support integrated community and family capacity development and, where this approach is inadequate, to provide humanitarian assistance to children affected by HIV/AIDS and to the families with whom they live.

Ainsworth, M. & Semali, I. 2000. The impact of adult deaths on children's health in Northwestern Tanzania. Policy Research Working Paper 2266. Washington, DC, World Bank Development Research Group, Poverty and Human Resources.

Desmond, C., Michael, K. & Grow, J. 2000. The hidden battle: HIV/AIDS in the family and community. Durban, South Africa, University of Natal Health Economics & HIV/AIDS Research Division.

Donahue, J. 1998. Community-based economic support for households affected by HIV/ AIDS. Discussion Papers on HIV/AIDS Care and Support No. 6. Arlington, USA, Health Technical Services project for the United States Agency for International Development (USAID).

Donovan, C., Bailey, L., Mpyisi, E. & Weber, M. 2003. Prime age adult morbidity and mortality in rural Rwanda: effects on household income, agricultural production and food security strategies. Kigali, Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Resources and Forestry, Food Security Support Project.

FAO. 2003. Measuring impacts of HIV/AIDS on rural livelihoods and food security, prepared by C. Shannon Stokes. SD dimensions, January (available at www.fao.org/sd/2003/ PE0102a_en.htm).

Foster, S. 1996. The socioeconomic impact of HIV/AIDS in Monze district Zambia. London, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Department of Public Health and Policy. (Ph.D. thesis)

Foster, G. & Williamson, J. 2000. A review of current literature of the impact of HIV/AIDS on children in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS 2000, 14(Suppl. 3): S275–S284.

Gilborn, L.Z., Nyonyintono, R., Kabumbuli, R. & Jagwe-Wadda, G. 2001. Making a difference for children affected by AIDS: Baseline findings from operations research in Uganda. New York, USA, Population Council.

Hepburn, A.E. 2001. Primary education in Eastern and Southern Africa – increasing access for orphans and vulnerable children in AIDS-affected areas. Durham, USA, Duke University, Terry Stanford Institute of Public Policy (available at www.usaid.gov/our_work/humanitarian_ assistance/the_funds/pubs/hepburnfinal.pdf).

Panpanich, R., Brabin, B., Gonani, A. & Graham, S. 1999. Are orphans at increased risk of malnutrition in Malawi? Ann. Trop. Paediatr., 19(3): 279–285.

Poulter, C. 1997. A psychological and physical needs profile of families living with HIV/AIDS in Lusaka, Zambia. Research Brief No. 2. Lusaka, United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF).

Robson, E. 2000. Invisible carers: young people in Zimbabwe's home based health care. Area, 32: 59–69.

SADC/FANR. 2003. The impact of HIV/AIDS on food security in Southern Africa – Regional analysis based on data collected from national VAC emergency food security assessments in Malawi, Zambia and Zimbabwe. Draft for stakeholder presentation, March, 2003. Southern Africa Development Community/Food Agriculture and Natural Resources Vulnerability Assessment Community.

Semali, I. & Ainsworth, M. 1995. The impact of adult death on the nutritional status and growth of young children. IXth International Conference on AIDS and STD in Africa. 10–14 December 1995. Abstract MoD066.

Sengendo, J. & Nambi, J. 1997. The psychological effect of orphanhood: a study of orphans in Raika district. Health Transit. Rev., 7(Suppl.): 105–124.

UNAIDS (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS)/UNICEF/ USAID. 2002. Children on the brink 2002 – a joint report on orphan estimates and program strategies. New York, USA, UNICEF (available at www.unicef.org/publications/index_4378.html).

UNAIDS/WHO (World Health Organization). 2002. AIDS epidemic update. December 2002. Geneva.

UNICEF. 2003a. Nutrition – Southern Africa humanitarian crisis. Presentation at the UN/SADC stakeholders meeting. Johannesburg, 11–12 June 2003 (available at sahims.net/temp_batchfiles/UNICEF% 20PRESENTATION%20JUNE%202003%20final.pdf).

UNICEF. 2003b. Statistics – Children orphaned by HIV/AIDS. (available at www.childinfo.org/eddb/hiv_aids/orphan.htm: accessed March 2005).

Urassa, M., Boerma, J.T., Ng'weshemi J.Z.L., Isingo, R., Schapink, D. & Kumogola, Y. 1997. Orphanhood, child fostering and the AIDS epidemic in rural Tanzania. Health Transit. Rev., 7(Suppl. 2): 141–153.

World Bank. 1997. Confronting AIDS: public priorities in a global epidemic. New York, USA, Oxford University Press.

Yamano, T. & Jayne, T.S. 2002. Measuring the impact of prime-age adult death on rural households in Kenya. Staff Paper 2002-26. East Lansing, USA, Michigan State University, Department of Agricultural Economics.

A . D E W A G T A N D M . C O N N O L L Y

There are 40 million people living with HIV/AIDS in the world, 29.4 million of whom are in Africa. By 2010, 5.8 percent of all children in the region will be orphaned by AIDS. Children whose parents are sick and dying or have died face various problems beyond the loss of family and identity. AIDS increases poverty in families as time and money are spent to care for sick relatives. Without adequate care and support children are at increased risk of malnutrition and reduced opportunity for education. Orphaned children face increased food insecurity and stigmatization and discrimination, and they may have fewer economic opportunities. They can be exposed to exploitative child labour and abuse and become more vulnerable to HIV infection. This article presents data from several studies in Africa that explore the impact of HIV/AIDS on children's education, food security, nutrition and health and explores the combined developmental and humanitarian response required to address these challenges.

Quarante millions de personnes vivent avec le VIH/SIDA dans le monde, dont 29,4 millions se trouvent en Afrique. D'ici à 2010, 5,8 pour cent des enfants de cette région seront orphelins du SIDA. Les enfants dont les parents sont en fin de vie ou décédés, rencontrent divers problèmes qui vont au-delà de la perte de famille et d'identité. Le SIDA accentue la pauvreté des familles dès lors que du temps et de l'argent sont consacrés aux soins des malades. Privés de soins adéquats et de soutien, les enfants sont exposés à des risques de malnutrition accrus tandis que leurs perspectives d'éducation s'amenuisent. Les risques d'insécurité alimentaire, de stigmatisation et de discrimination des enfants orphelins sont plus importants et leurs possibilités économiques peuvent être amoindries. Ils risquent d'aller gonfler les rangs de la main-d'œuvre infantile, peuvent être victimes d'abus et deviennent plus vulnérables à une infection par le VIH. Le présent article fournit des données tirées de plusieurs études réalisées en Afrique concernant l'impact du VIH/SIDA sur l'éducation des enfants, leur sécurité alimentaire, leur nutrition et leur santé, et étudie la réponse à apporter, en termes à la fois humanitaires et de développement, face à de tels défis.

En el mundo hay 40 millones de personas aquejadas del VIH/SIDA, de las que 29,4 millones viven en África. Para 2010, el 5,8 por ciento de todos los niños de la región serán huérfanos del SIDA. Los niños cuyos padres están muriendo o han muerto se enfrentan con diversos problemas, además de la pérdida de su familia y su identidad. El SIDA aumenta la pobreza de las familias, ya que se emplea tiempo y dinero en cuidar a los parientes enfermos. Si no reciben atención y cuidados adecuados, los niños corren un mayor riesgo de malnutrición y sus oportunidades educativas disminuyen. Los niños huérfanos se enfrentan con un aumento de la inseguridad alimentaria, la condena moral y la discriminación y es posible que tengan menos oportunidades económicas. Corren el riesgo de ser explotados como mano de obra infantil, sufrir abusos y ser más vulnerables a la infección por VIH. En este artículo se ofrecen datos de diversos estudios realizados en África sobre los efectos del VIH/SIDA en la educación, la seguridad alimentaria, la nutrición y la salud de los niños, y sobre las medidas tanto humanitarias como de desarrollo que han de adoptarse para responder a estos desafíos.