Amand Shah

Ministry of Agriculture, Government of India, Room No. 233, Krishi Bhawan, Ra. Marg, New Delhi 110001, India; e-mail: [email protected]

Abstract

With a view to modernize, upgrade, standardize and enhance the somewhat outdated plant quarantine system, its capacities and the related legal and administrative framework, the Government of India has recently approved the notification of a new Plant Quarantine Order for the country. This new Order is a step forward in harmonizing India’s regulatory framework with the International Plant Protection Convention and internationally accepted standards and the tenets of the SPS Agreement of the World Trade Organization. Other supporting and managerial steps are also being taken to improve, to international standards, the entire gamut of the country’s quarantine activity and phytosanitary border controls, including import and export inspections, on-field surveillance for pests and vectors, treatment standards and processes, and certification methodology. India is making imports of plants and plant materials subject to pest risk analysis to protect its crops from risk of introduction of alien pests. Efforts are also under way to improve the export certification process and standards to ensure that such phytosanitary certification gives an assurance of freedom from quarantine and regulated pests and vectors, including alien species for importing countries. The details and features of the legislative and executive initiatives, and the rationale and methodology adopted are outlined in this paper.

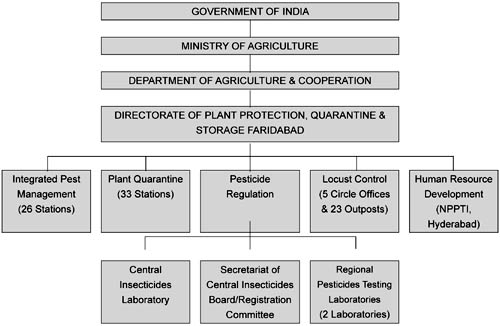

Plant quarantine operations in India are carried out by the Directorate of Plant Protection, Quarantine and Storage, which functions under the aegis of the Ministry of Agriculture. The administrative structure of plant quarantine is shown in the organizational chart (see figure 1).

The development of the new Plant Quarantine (Regulation of Import into India) Order, 2003 (referred to hereafter as “the new Order”) reflects the primary plant quarantine concerns of the Government of India. These are:

to prevent the introduction and spread of exotic pests that are destructive to the country by regulating the import of plants and plant products through adequate policy and statutory measures

to support India’s agricultural exports through credible export certification

to facilitate safe global trade in agriculture by assisting producers, exporters and importers and by providing technically comprehensive and credible phytosanitary certification.

Before the new Order was gazetted on 18 November 2003, the hitherto existing plant quarantine statute and regulations dated back as early as 1914. Until recently, regulatory measures in India operated on the basis of The Destructive Insects and Pests Act, 1914, which was promulgated to prevent introduction and spread of destructive pests affecting crops, and the Plant, Fruits and Seeds (Regulation of Import into India) Order, 1989. Some other Rules were promulgated for regulating import of live insects (1941), fungi (1943) and cotton (1972).

The New Seed Policy, 1988 was formulated to provide Indian farmers with access to the best available seeds and planting material, domestic and imported.

Fig. 1: Organizational chart of Indian plant quarantine structure.

The Plants, Fruits and Seeds (Regulation of Import into India) Order, 1989, prohibiting and regulating the import into India of plants, plant materials and the like, is based on post-entry quarantine checks. It has now been replaced by the new Order of 2003.

There were many reasons prompting the development of new legislative provisions for plant quarantine in India. They include the following:

Liberalized trade in agriculture as a consequence of the WTO Agreements, although offering economic opportunities, also implied fresh challenges of amplified pest risks, a corollary to the increased volumes and array of international trade in agricultural commodities.

With diverse agroclimatic zones, varied agricultural produce and surplus food production, India finds itself in a position to exponentially expand its agricultural trade. However, what were required were accreditable national standards for all critical phytosanitary activities. Relevant entities and other interested parties invariably felt the need for compliance with stringent international phytosanitary regulations.

There was an urgent need to fill the gaps in the existing plants, fruits and seeds order of 1989, namely by regulating the import of germplasm, genetically modified organisms and transgenic plant material, as well as live insects and fungi (including biocontrol agents etc).

India needed to facilitate safe conduct of global trade in agriculture and thereby fulfil its legal obligations under the relevant international agreements.

It was necessary to protect the interest of the country’s farmers by preventing the entry, establishment and spread of destructive pests, vectors and alien species.

It was necessary to protect the national plant life and environment.

It was necessary to safeguard the national biodiversity from threats of invasive alien species.

The need was felt for incorporation in regulation of additional special declarations for the freedom of import commodities from quarantine and alien pests. These declarations would be based on standardized pest risk analysis, particularly for seeds and planting materials.

The 2003 new Order for plant quarantine in India has widened the scope of plant quarantine activities with the incorporation of additional definitions. It also makes pest risk analysis a precondition for imports.

It places a prohibition on the import of commodities contaminated with weeds and/or alien species. Import of packaging material of plant origin is restricted unless the material has been treated.

The new Order includes provisions for regulating the import of:

Agricultural imports are now classified as: (a) prohibited plant species; (b) restricted species where import is permitted only by authorized institutions; (c) restricted species permitted only with additional declarations of freedom from quarantine pests and subject to specified treatment certifications; and (d) plant material imported for consumption or industrial processing permitted with normal phytosanitary certification.

A permit requirement is now enforced on imports of seeds, including flower seeds, propagating material and mushroom spawn cultures. Additional declarations are specified in the new Order for the import of 144 agricultural commodities, specifically listing as many as 590 quarantine pests and 61 weed species.

Notified points of entry have increased dramatically: there are now 130 such entry points, where previously there were 59. The new Order also rationalizes the structure of certification fees and inspection charges.

India’s new Order for plant quarantine aligns with the framework of the International Plant Protection Convention in several important ways:

The phytosanitary measures are designed to prevent global spread of noxious pests and are based on justified scientific principles with pest risk analysis as the cornerstone.

Provisions have been made applicable to packages and transportation.

Inspection and certification provisions accord with Article IV of the IPPC.

Phytosanitary certificates are in the format of Article V of the IPPC and according to the plant quarantine requirements of the importing country. They are to be issued after careful inspection and the required treatment.

There is emphasis on capacity enhancement and development and training of staff.

The new Order has been hosted on the Web site of the Ministry of Agriculture (and is available at www.agricoop.nic.in) and made accessible to everyone. It is transparent and applies uniformly to all exporting countries or parties.

Features of the new regulation of imports include the following:

Separate formats have been devised for applications for the issue of import permits and also for the permit letters issued for consumption purposes as opposed to those for propagative plant materials.

Commercial imports of seeds of coarse cereals, pulses, oil seed, fodder crops and planting materials of fruit plant species require prior clearance.

Applications for seeds and planting materials must be accompanied by (1) a registration certificate issued by the National Seeds Corporation or the Director of Agriculture or Director of Horticulture of the state government and (2) a certificate of approval of post-entry quarantine facilities issued by the designated inspection authority.

Permits are to be issued within a maximum period of three working days of submission of an application.

Pest risk analysis has been made a precondition for import of new agricultural commodities.

Permits for import of soil or peat and for import of live insects, microbial cultures or biocontrol agents are to be issued only by the Plant Protection Adviser, the technical head of the plant quarantine service.

Permits for import of germplasm, genetically modified organisms and transgenic material are to be issued by the director of the National Bureau of Plant Genetic Resources, New Delhi.

Issued permits are valid for six months. This may be extended a further six months.

Permits are not transferable and no permits are to issued for landed consignments.

Relaxations from the conditions of the new Order, necessitated by emergency or unforeseen circumstances, are to rest with the Ministry of Agriculture.

Various initiatives and activities are under way for upgrading and strengthening plant quarantine facilities:

by 2005, 35 new plant quarantine stations to be opened across the country at all major and minor ports

development of:

an integrated information management system

an integrated pest risk analysis system and a national pest risk analysis unit for conducting integrated pest surveillance

an integrated phytosanitary border control system

a national phytosanitary database

a national management centre for phytosanitary certification to continuously review the national standards for export phytosanitary certification.

establishment of advanced molecular diagnostic facilities at major plant quarantine stations for rapid pathogen detection

computerization and networking of all the plant quarantine stations

standardization of the export certification process so that uniform and credible certificates with a common format and seal are issued by all phytosanitary certification authorities, both in central and state governments, across the country

human resource development and skill upgrading or training programmes for scientists, researchers and others

obtaining ISO quality certification for major plant quarantine stations

production of guidelines for training of plant quarantine inspectors

production of guidelines for the development of new disinfestation techniques and vapour heat treatment of fruit fly host commodities

development of fumigants as an alternative to the ozone-depleting methyl bromide

development of international standards for phytosanitary measures

planned production of guidelines for accreditation of post-entry quarantine facilities and inspection.

Pest risk analysis plays a key role in the new Order for plant quarantine in India. An action plan for pest risk analysis was drawn up, to take effect from December 2003. A major feature of the plan is the establishment of a national pest risk analysis unit.

The action plan includes organizing PRA training, establishing working groups and holding a workshop attended by national and international experts to prioritize crops and commodities for pest risk analysis. Some 36 commodities (see box) were selected for which a pest database is under development. Detailed pest risk analyses for these commodities have begun, with the aim of completing the pest risk analysis for 13 commodities each year.

|

India’s priority crops for pest risk analysis |

||

|

strawberry |

banana |

kiwi |

|

musk melon |

watermelon |

pears |

|

mandarin |

cashew nut |

apple |

|

grape |

citrus fruits |

lentil |

|

red beans |

chickpea |

jute |

|

black gram |

green gram |

cotton |

|

wheat |

rice |

barley |

|

maize |

baby corn |

pearl millet |

|

sorghum |

lettuce |

garlic |

|

broccoli |

potato |

Chinese cabbage |

|

mustard |

sunflower |

safflower |

|

linseed |

castor |

rape seed |

The national integrated pest management (IPM) programme is considered to be the mechanism with which to prevent and control the threat posed by invasive alien species within the country. State governments, non-governmental organizations, private sector organizations, research institutions and farmer self-help groups are all increasingly involved in the surveillance and detection of pests and diseases. They are capable of taking environmentally friendly corrective action within the IPM scheme.

International cooperation has helped in dealing with migratory locust, a pest of great concern for the Asian region. India maintains active coordination with FAO and with neighbouring countries for surveillance, early detection and control measures for locust. There was no major incidence reported in the region in 2003.

A peculiar cyclic problem, thankfully confined to a small hilly region of north-eastern India, relates to unexplained but sudden surges in rodent population and activity. The menace reaches peak proportions at the same time as the periodic gregarious flowering of bamboo. The problem has surfaced again and is likely to peak in 2006-2007 when the next mass flowering is predicted, causing crop losses. Research and preventive control measures under way include study of the rodent characteristics, damage capacity, pathways associated with the pest and an environmentally friendly control strategy. The traditional knowledge of the local agrarian community of the region is also utilized.

Of particular interest to India is research being conducted to study the impact of climate change on the threat posed by invasive alien species. The topic is of greater importance since a serious white woolly aphid infestation of the sugarcane crop in parts of peninsular India in 2002 caused substantial crop damage and losses. This pest had never before infested sugarcane in India.

The task of research, future prevention and control measures for white woolly aphid is being handled by the Ministry of Agriculture in coordination with other central government departments, concerned state governments, the Indian Council of Agricultural Research, other research institutions and agriculture universities, private sector organizations and sugar factories. The severity of the white woolly aphid infestation, recorded in 2002 in over 200 000 ha of sugarcane, has subsequently reduced substantially. However, almost 75 000 ha of the crop was still infested in 2003 and the matter continues to be of concern.