“Our yields were 0.8 tons of wheat, now they are 2.6. But those early sources of growth are no longer available. We now face problems of salinity, shortage of micronutrients, the lesser availability of water, pest resistance and resurgence, and expensive fertilisers. Our task has become complex. We need to address these challenges and farmers must come along”.

Dr Naeem Hashimi, Pakistani wheat breeder and member of

Pakistan Agricultural

Research Council, interview August 20, 2004

Niels Röling notes in his paper that farmers everywhere face new challenges. Climate change, competing claims on natural resources, globalization, price squeeze and competition, loss of resilience of (agro-) ecosystems, advance of technology, increasing livelihood needs, and increasing exploitative pressure are making their lives and livelihoods increasingly difficult.

And yet we need farmers to produce sufficient and safe food and fibre, to restore biodiversity and hydrological systems, to create markets for our goods and to participate in building a stable civil society.

For this to happen, he believes, an enormous transformation is required. There needs to be a shift from the push on technology and expert knowledge to the co-creation of knowledge and empowerment. Farmers need to be allowed to become partners in making choices. And there needs to be a recognition that developing farmers' countervailing power is the fastest route to rural development.

Niels Röling points out that the words “Research, Extension and Education” mean many different things to different people. To a student in a US Land Grant University, they reflect the Land Grant ideology that regards the integration of these tasks, coupled to independence from policy, as the source of success and power, if not superiority of American universities, and the secret behind the efficiency of American agriculture. For the average agriculturalist in Europe, “Research and Extension” refer to services that have been the responsibility of the state but are now increasingly privatized. They have been widely used as policy tools to bolster agricultural productivity and the competitive position of national agricultural industries. The word “Education” invokes qualification and competence-building especially of farmers and their children.

Finally, in most developing countries, the words “Research, Extension and Education” are not necessarily linked. Research and Extension usually are the responsibilities of different directorates of the Ministry of Agriculture, while Education is the responsibility of another Ministry. Thoughts would not immediately turn to agricultural education. What the three have in common is not immediately clear.

The paper defines development communication as a process which “seeks to understand, foment, facilitate and monitor the process by which a set of actors moves towards synergy. It focuses on the participatory definition of the contours of the theatre, the composition of the actors in it, their understanding of their complementarity and interdependence, their linkages, interaction, conflicts, negotiated agreements and collaboration.”

Niels Röling believes it is not useful to consider innovation the outcome of transfer or delivery of results of scientific research to “ultimate users” or farmers. Hence it is not useful to consider development communication as the tool to improve the delivery mechanism.

The paper goes on to explain the concept of an AKIS, which is, first of all, a way of looking at the world. It is not a predefined construct. It has to do with networks of multiple stakeholders, with learning and with interaction. It has to do with the way people make sense of the future and of the opportunities that are available. An AKIS is not a predefined construct, it emerges from interaction (usually temporary) between actors who mutually complement one another's contributions. The actors are aware of the fact that they form a system and do their best to maintain it.

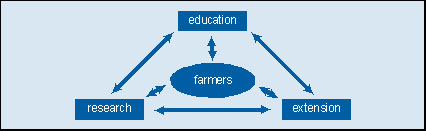

An AKIS links people and institutions to promote mutual

learning and generate, share and utilize agriculture-related technology,

knowledge and information. The system integrates farmers, agricultural

educators, researchers and extensionists to harness knowledge and information

from various sources for better farming and improved livelihoods. This

integration is suggested by the “knowledge triangle” displayed below.

Rural people, especially farmers, are at the heart of the

knowledge triangle. Education, research and extension are services – public or

private – designed to respond to their needs for knowledge with which to

improve their productivity, incomes and welfare, and manage the natural

resources on which they depend in a sustainable way.

A shared responsiveness to rural people and an orientation

towards their goals ensures synergies in the activities of agricultural

educators, researchers and extensionists. Farmers and other rural people are

partners within the knowledge system, not simply recipients.

Niels Röling continues by explaining the three narratives that have emerged from the experience of the mid-Western states of the US since the early 1940s. These underpin the discourse about research, extension and education. They are:

Any discussion about development communication must start with reflection on these three narratives. They are the product of certain historical conditions and a phase of agricultural development that is not necessarily ubiquitous or very relevant from a development communication perspective.

This is perhaps the best-known narrative. The basic notion is that innovations, novel ideas, autonomously diffuse among members of a relatively homogeneous population after their introduction from outside, either through a change agent, through people who straddle the local and external worlds, or through other media. This diffusion process usually starts slowly and then gathers steam, so that the “diffusion” curve marking the rate of adoption of the innovation by individuals over time typically has the shape of a growth curve. One can distinguish people who adopt fast and people who are slow to follow. Many studies have been carried out to identify the discriminating characteristics. This has led to a rather circular argument: research shows that “progressive” farmers (i.e. those with large farms, education, access to outside agencies, etc.) are the ones who are early to adopt. Therefore, extension efforts should focus on these farmers to achieve rapid diffusion. But these farmers were early to adopt partly because extension agents already pay a lot of attention to them. Diffusion studies often have provided the rationale for what can be called “the progressive farmers” strategy.

The popularity of the diffusion of innovations narrative can be explained by the fact that empirical studies of cases where an innovation diffused to a large proportion of the farmers in a population in a very short time has created an expectation that technologies, once introduced to few farmers through extension and research efforts, will diffuse rapidly on their own and multiply the public sector effort. “Diffusion works while you sleep.”

The agricultural treadmill model has the following key elements:

Röling believes that policy based on the treadmill can have positive outcomes. For one, the advantages of technological innovation in agriculture are passed on to the customer in the form of cheap food. For example, in the Netherlands an egg still has the same nominal value as in the 1960s. The very structure of agriculture makes it impossible for farmers to hold on to rewards for greater efficiency. Meanwhile, labour is released for work elsewhere. One farmer can now easily feed a hundred people. When the treadmill runs well at the national level in comparison with neighboring countries, the national agricultural sector improves its competitive position. Furthermore, farmers do not protest against the treadmill if they profit from it. And finally, the treadmill will continue to work on the basis of relatively small investments in research and extension. These have a high rate of return.

But there are also disadvantages. It is not consumers but input suppliers, food industries, and supermarkets who capture the added value from greater efficiency. Large corporations are well on their way to obliterate competition in agriculture. Only farmers are squeezed. The advantages of the treadmill diminish rapidly as the number of farmers decreases and the homogeneity of the survivors increases. The treadmill has a limited life cycle as a policy instrument. Eventually, the treadmill is unable to provide farmers with a parity income. That becomes clear from the subsidies farmers need. That flow of subsidies should be reorientated, but does not as yet have a good alternative.

The competition among farmers promotes non-sustainable forms of agriculture (use of pesticides and hormones, loss of bio-diversity, unsafe foods, etc.). The treadmill leads to loss of local knowledge and cultural diversity.

A global treadmill unfairly confronts farmers with each other who are in very different stages of technological development, and have very different access to resources. This effect is only exacerbated by export subsidies paid to farmers in the North to overproduce. It leads to short-term adaptations that can be dangerous for long-term global food security.

The third narrative is the transfer of technology. Science is the growth point of human civilization. Science ensures progress. Extension delivers these ideas to users. Transfer of technology assumes a one-way and uninterrupted flow of technologies from fundamental scientists, to ultimate users via various intermediaries and delivery mechanisms. It therefore is also called the linear model.

| Transfer of technology – linear model | |

|

▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ |

There is a difference between the transfer of knowledge, and the co-creation of knowledge. In the first situation, an expert, such as an agricultural extension agent or a medical specialist, seeks acceptance of, or compliance with, his way of looking at the world or of solving a problem. In the second situation, a group of stakeholders with different and often complementary experiences or knowledges agree on ways forward to improve their shared problem.

|

Key Factor |

Transfer of Knowledge |

Co-creation of knowledge |

|

Nature of problem |

Lack of productivity or Efficiency |

Lack of concerted action |

|

Key actors involved |

Expert and target audience |

Interdependent stakeholders in a contested resource or shared problem |

|

Desirable practices |

Target audience uses improved component technologies |

Stakeholders agree on concerted action (e.g., integrated catchment management) |

|

Desirable learning |

Target audience adopts technologies developed by expert. In best situation: diffusion of innovations among members of target audience. Learning of expert is not relevant in this situation |

Through interaction, stakeholders learn from and about each other. They try out ways forward in joint experimental action that allows discovery learning. They become able to reflect on their situation and empowered to deal with it. |

|

Facilitation |

Expert demonstrates, persuades, explains, promotes. |

Trained facilitator brings together stakeholders so as to allow interaction. He/she creates spaces for learning and interaction (platforms). He/she managers the process, not the content. |

Röling points out that West African farmers are among the most innovative in the world. Their indigenous systems represent sustainable, resilient and intelligent forms of agriculture that have supported expanding communities over the centuries. They took up maize, Phaseolus beans, cassava, tomatoes and many other current staple crops that originate from Latin America in fairly recent times. West African farmers have coped with the rapid population increase during the last 20 years and have adapted their farming systems to deal with new problems such as declining soil fertility, declining rainfall and weed emergence. Gold Coast tribes of old have made cocoa Ghana's major export crop without any government assistance, a development that only came to a halt when excessive taxation virtually killed the goose that laid the golden eggs.

The lack of impact of agricultural research in West Africa cannot be blamed on lack of innovativeness on the part of the farmers.

|

Linear thinking and mucuna beans |

|

However poor some West African farmers might be, all have veto power when it comes to accepting the results of agricultural research: there is no way that one can force autonomous farmers to adopt technologies. A typical example is an important and highly regarded international agricultural research agency in West Africa. Its concern is with soil fertility management. After excellent research, it had come to the conclusion that improving soil fertility in West Africa is a question of soil organic matter first and nutrients second. This research showed that planting, and ploughing under, the luxurious growth of the velvet bean (Mucuna spec.) is the most efficient way to increase soil organic matter. When this thinking was made public, it predictably drew some criticism. After all, mucuna has been tried time and again. Invariably farmers complain that one cannot eat the beans, that it is hard and painful to incorporate the vegetative matter into the soil, that the bean occupies the land for two seasons during which food production is impossible, etc. Nowhere in West Africa has mucuna been taken up as a green manure. Undaunted, the representative of the agency proclaimed that this was not his but the farmers' problem and that if they wanted to escape from the vicious circle of land degradation and poverty they should plant mucuna. As a scientist he knew what worked, acceptability by farmers was not his problem. This approach is a typical example of linear thinking. The scientist thinks he is right and his lack of impact is the farmers' problem. |

Niels Röling asks: Why has it not been possible for agricultural research to link into this rich lode of innovativeness? He gives three main reasons:

Farmers in West Africa have no control over commodity prices, input-selling companies, government produce buying schemes and marketing boards, policies to import cheap foodstuffs that undercut local farmers and so forth. If one compares this situation with industrial countries, the sharp contrast stands out. In most industrial countries, farmers have power that is disproportionate to their numbers, but reflects the fact that they collectively own most of the land of the country. They are extremely well organized.

Based on the experience in industrial countries, one could say that the fastest way to develop West African agriculture is not to strengthen what in French-speaking countries are called les organismes d' intervention, but farmers' countervailing power vis-ŕ-vis those organismes.

The absence of a network of service institutions in which agriculture is embedded in West Africa severely constrains agricultural development. Time and again, pilot projects are mounted that artificially create the conditions for a rapid productivity growth. Then, when it comes to scaling up their indeed impressive effects from the pilot level and to replicate the project on a larger scale through existing institutions, the effects collapse. The existing institutions are simply incapable of creating the conditions in which small-scale West African farmers can apply their innovativeness to the benefit of the public cause. As it is, in the absence of a decent monetary income, they focus on subsistence production and are “organic by default”. Inputs are too expensive to apply, and producing a surplus is irrational.

The situation described has important implications for agricultural research. It is irrelevant to assume goals for technology development, such as productivity increase. It is equally irrelevant to implicitly assume that conditions can be created that will allow large-scale adoption of a technology, if those conditions are not available at present. Further, it is irrelevant to develop technologies that can only be adopted as long as special conditions can be created through small-scale projects.

At present, things have begun to improve in the region. Urban development creates markets for food commodities that cannot be imported cheaply, such as cassava and various vegetables. The fact that farmers increasingly have alternative sources of income (e.g. through urban wage employment, emigration, etc.) means that they no longer have to accept any monetary income they can make from export crops. Governments are forced to offer farmers better deals. In other words, new opportunities seem to be emerging, but these are by no means automatic or obvious.

Niels Röling notes : “Our (superficial) survey of the West African context shows that it is very different from the one in which the three interlocking dominant narratives emerged. But in a situation where farmers do not have clout, it is all too easy for people, explicitly including Africans educated in the `Western tradition', to, often implicitly, make decisions that are based on an industrial country context. The most glaring example of this is the tacit assumption that agricultural research serves productivity increase in terms of tonnes per hectare. One scheme after another tries to achieve this. The predictable result is overproduction, a rapid fall in prices, yet another wrong prediction of the internal rate of return of a project, and disillusioned farmers. There must be another way. That is the challenge for development communicators.”

Niels Röling then outlines the main components of the way forward:

According to Sir Albert Howard, that great pioneer of organic agriculture who designed large-scale agricultural production systems that did not depend on chemical fertilizers, “the approach to the problems of farming must be made from the field, not from the laboratory. The discovery of things that matter is three-quarters of the battle. In this the observant farmer or labourer, who have spent their lives in close contact with Nature, can be of the greatest help to the investigator”.

Farmers have veto power when it comes to participating in induced innovation. There is no way one can force them to innovate. Therefore, one must listen to them, take them seriously, and involve them in one's work. There seems no other way. Development communicators in Research, Extension and Education, especially if they subscribe to the Millennium Goals, must ensure that farmers are given a voice in the development process.

|

Questions for effective research |

|

In Cochabamba, Bolivia, a development project sought to regenerate ancient degraded mountain lands in the High Andes using cactus pear for human, cattle and cochineal feed and for revegetating the barren slopes. Out of this experience, A. Tekelenburg, who worked for eight years in Cochabamba, drew conclusions for the types of “agricultural research” that were required for a development project that is effective in reaching the rural poor. He suggests the following fundamental questions that must all be answered to achieve “development” outcomes.

|

One of the principles of Integrated Pest Management (IPM) is that “the farmer is an expert”. This principle is increasingly recognized all over the world. Farmers may be experts, but they lack a collective voice, at least in many developing countries. This lack of influence of farmers is beginning to be a handicap. In the early days of the Green Revolution, farmers were more or less considered as the lowest rank in the hierarchy. Scientists and administrators determined what needed to happen and farmers were told what to do. In many countries, if farmers did not like the new “high yield variety” and continued to plant their old varieties, the authorities would not hesitate to call in the army or police to destroy the old crop. Prices were set at the national level, uniform technical packages of varieties, fertilizers and pesticides were recommended across huge domains assumed to be homogeneous. It worked for a while. Now that second generation problems are beginning to be felt (such as pest resistance and emergence), and now that the next advance must come from capturing diversity, a powerless peasantry is no longer the right partner for agricultural development. Farmers must have a voice, and they must be given full opportunity to help make development work.

A key to finding alternatives to the deadly mantra of the three narratives that emanates from the cutting-edge scientists, the market fundamentalists, and the top managers, is experimentation. A great number of very important lessons are being learned every day in most countries in experiments with different approaches. Niels Röling notes that: “It is time to shake off our complacency and dare to accept that we have not done very well in terms of development and therefore that we need to accept that the only thing we know is that we don't know. We need to make a greater effort to learn together around concrete field experiments that pioneer new approaches.”

It is an all too common experience to see good initiatives thwarted by those who see the world as a set of variables to be manipulated, ie, the people who set the conditions in which you must work. It is impossible to achieve goals without involving these “higher” levels. I believe that development communicators in research, extension and education have an important task in bringing about transformational learning at these higher levels.

The working group gives a number of definitions for development communication in Research, Extension and Education. It identifies key challenges, particularly the fact that dominant models do not provide desired outcomes in the longer term. It gives a number of successful examples of Communication for Development in this area in different parts of the world.

It then goes on to make recommendations when scaling up, which include knowledge and understanding of Development Communication at all levels and the fact that political context is key. Recommendations to practitioners and donors include a need for participatory baseline formulations, a multidisciplinary approach in communication from beginning, and flexibility.

Recommendations to the UN include recognizing that Development Communication is essential to achieve impact in rural development; a call for governments to implement a legal and supportive framework favouring the emergence of a pluralistic information system; and the setting up of an interagency group to analyse communication experiences in Research, Extension and Education, and develop a framework and a common approach to indicators of success.