IDENTITY

Biological features

Shell broadly oval to quadrate, umbones distinctly anterior. Posterior hinge line straight, posterior margin truncate, anterior hinge line grading into the down-sloping anterior margin. Prominent posteriorly, where the shell is conspicuously decussate. Sculpture of fine concentric striae and bolder radiating lines. Growth stages clear. Lunule and escutcheon poorly defined. Each valve with three cardinal teeth: centre one in left valve, and centre and posterior in right are bifid. Pallial line and adductor scars distinct. Pallial sinus U-shaped, not extending beyond mid-line of shell, but reaching a point below the posterior part of the ligament. Lower limb of sinus distinct from pallial line for the whole of its length. Inner surfaces glossy white, often with yellow or orange tints, and with a bluish tinge along dorsal edge. Cream, yellowish, or light brown, often with darker markings.

Images gallery

|

|

|

|

Ruditapes decussatus |

Grooved carpet shell harvesting |

PROFILE

Historical background

The harvesting of Ruditapes decussatus mainly occurs in Spain and France. In Spain, early records of mollusc fishing and consumption from the 16th century are mainly about the flat oyster, and only rarely about clams, but they do mention the marketing of clams in Portugal and other places. Intensive fishing for clams began in 1926 and 1927. Digging was indiscriminate, as fishermen used prohibited tools and took clams of all sizes. In Spain, near San Simon, in the Ria de Vigo, fishermen found one natural clam population and depleted it in a short time. The fishermen sold cases of clams weighing 54 kg for only 5 pesetas (EUR 0.03). Later, when competition increased, the price became 30 pesetas (EUR 5.55). In 1935, clam fishing was regulated and the quantity of clams each fisherman was allowed to take during each low tide was 14 kg, and the season was closed from May to October. At that time, there were 6 130 walking harvesters and 1 480 others using boats near San Simon.

Despite the large clam harvests, their repopulation is rapid. In 1948 it was estimated that populations of Ruditapes decussatus and Venerupis pullastra in the Ria del Burgo (Spain) recovered in less than a year from a density of 1-5 to 30-50 clams/m2. Production of clams from 1927 to 1953 in the Ria de Vigo ranged from 28 719 to 652 890 kg. Around 1956, clam production in the Galician region was about 60 percent of national production. The season was from October to March, while in areas nearest to the mouth of the Ria about 60 boats worked and obtained 3 000 kg per day. These differences were associated with the great mortality that occurred in the inner part of the Ria de Vigo, due to heavy rains that produced a rapid drop in salinity. In the ensuing years, clam production has been variable, and statistical data on total production is sparse.

Despite the large clam harvests, their repopulation is rapid. In 1948 it was estimated that populations of Ruditapes decussatus and Venerupis pullastra in the Ria del Burgo (Spain) recovered in less than a year from a density of 1-5 to 30-50 clams/m2. Production of clams from 1927 to 1953 in the Ria de Vigo ranged from 28 719 to 652 890 kg. Around 1956, clam production in the Galician region was about 60 percent of national production. The season was from October to March, while in areas nearest to the mouth of the Ria about 60 boats worked and obtained 3 000 kg per day. These differences were associated with the great mortality that occurred in the inner part of the Ria de Vigo, due to heavy rains that produced a rapid drop in salinity. In the ensuing years, clam production has been variable, and statistical data on total production is sparse.

Main producer countries

Ruditapes decussatus is cultured from the Atlantic coast of France, Spain, Portugal and in the Mediterranean basin.

Main producer countries of Ruditapes decussatus (FAO Fishery statistics, 2006)

Habitat and biology

The grooved carpet shell lives burrowed in sand and silty mud. It is a lamellibranch bivalve mollusc that filters water through its two siphons (one in and the other out) catching organic matter (detritus) and phytoplankton as food. The gills are two pairs of plates composed of filaments. Clams live on the sandy beaches of the Rias (flooded river valleys). Ruditapes decussatus is buried 15-20 cm deep in the sand from the middle of the intertidal zone to a depth of a few metres. Its sexes are separate, although hermaphrodites can be found infrequently. Reproduction is external and takes places mainly during summer in the wild, and/or on hatcheries. In spring, clams can be artificially conditioned for hatching with higher temperature water and abundant food. The larvae swim freely for 10-15 days before settling as spat of about 0.5 mm on a sand and silty mud substrate.

PRODUCTION

Farmers obtain seed from their own parks (protected bottoms) or from the natural clam populations in the spring. They dig the clam seed with sand using a small shovel, pass it through a sieve to retain the seed, take it to their Ongrowing parks, and spread it in densities of about 800 clams/m2. They may also dig adult clams from seaport areas and spread them in their parks. Periodically, they have to clean their parks of predators and mud.

Seed can also be obtained from hatcheries, where breeders, not exceeding 40 mm are maintained for 30-40 days at 20 °C. Breeders are fed with unicellular algae until the induction of the liberation of gametes. Gamete liberation can be induced by raising the temperature from 10 to 26 °C, maintaining it at that temperature for 30 minutes and then reducing it to 15 °C for several minutes; the cycle of raising temperature to 26 °C and lowering it again is then repeated until gametes are liberated. The addition of sperm from a sacrificed animal may also help in liberation. Fertilization occurs in small containers where the animals are isolated from each other. Eggs are filtered through a 40 µm mesh, and transferred to a 10 litre tank, where veliger larvae appear after 48 hours. Larvae are recollected in a 40 µm mesh and reared at densities of 3 000 larvae/litre. They are fed with unicellular algae every day during the first week and then every second day until metamorphosis.

Clams can be reared in nurseries within greenhouses, with controlled feeding by using unicellular algae or reared in meshed containers over culture tables. An alternative is to pump environmentally controlled water to inland tanks where clams are placed in cylinders of about 50 cm diameter and 20 cm long, with a bottom made of a rigid mesh.

Culture techniques are simple, consisting of regular maintenance of the substrate, avoiding algae, starfish and other predators; oxygenating the substrate; and maintaining an appropriate clam density and seeding juvenile clams.

In the Galician region, fishermen harvest clams by walking the intertidal areas and using special hand shovels, or sometimes by using the rakes that are normally used for keeping the culture beds clear of seaweed. Clams may also be harvested from boats, which may vary in size between less than 1 tonne and up to 12 tonnes. Some are propelled with oars, others with outboard engines. Various collection tools are used, including the 'rastro' and the 'raño' (rake), which are operated from the boats with the help of a long handle. The closed season is from March to October, and the minimum size allowed for Ruditapes decussatus is 30 mm. Some Galician areas have protected bottoms called 'parks' for the extensive culture of clams. In hand (walking) harvesting clams are harvested with the help of different types of small shovels; sometimes the rakes that are usually more employed for cleaning the parks of seaweeds are employed.

Fishermen bring their clams to depuration stations where they are held in tanks for at least 42 hours. The clams are then packed in net bags of 0.5 - 1 and 2 kg, and are destined to be canned or eaten fresh. They are transported by refrigerated trucks which maintain their temperature at 3 - 10 °C; the clams have a shelf life of 5 days. Canned clams are prepared with vinegar and various sauces. In the Galician region, the most popular meal with clams is 'ameixas a marineira' (mariner clams). The clams are opened in salted water and cooked with a special sauce (onions, garlic, parsley, bread grind and white wine).

Production costs are greatly influenced by the socio-economic environment and the size of seed supplied. If nursery time starts in spring, harvesting occurs in the late fall or early winter of the following year. Important factors in total costs are seabed leases or exploitation charges hatchery and nursery facility costs, management and harvesting tools and labour.

Ruditapes decussatus is often grown with other bivalves (Venerupis pullastra, Venerupis rhomboideus, Venerupis aurea, Dosinia exoleta and Tellina incarnate). Their main predators are shore crabs (Carcinus maenas); starfish (Asteria rubens and Marthasterias glaciais); gastropods (Natica sp.); and birds (Larus sp). An individual Carcinus maenas (6.5 cm width) can consume 5-6 clams per day.

Suppliers of pathology expertise

The following can provide expertise in this topic:

Dr. Antonio Figueras

Instituto Investigaciones Marinas, CSIC Spanish National Reference Laboratory for Mollusc Diseases

Fax: +34 986 292 762

E-mail: [email protected]

Dr. Isabelle Arzul

IFREMER, Laboratoire de Génétique et Pathologie

Fax: +33 5 46 36 37 51

E-mail: [email protected]

Dr. E.M. Burreson

Director for Research and Advisory ServicesVirginia Institute of Marine ScienceCollege of William and Mary

Fax: +1 804 684 7097

E-mail: [email protected]

Dr. S. Bower

Department of Fisheries and Oceans Pacific Biological Station3190 Hammond Bay Road Nanaimo

Fax: +1 250 756 7053

E-mail: [email protected]

Dr. Jorge Cáceras Martínez

Instituto de Sanidad Acuícola, A.C.

Fax: +52 646 1783473

E-mail: [email protected]

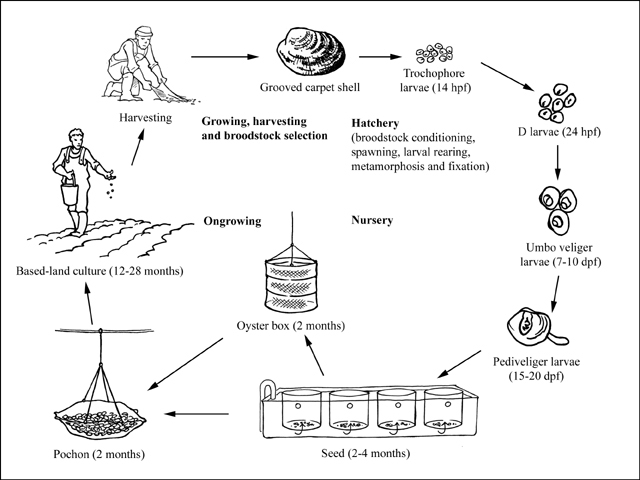

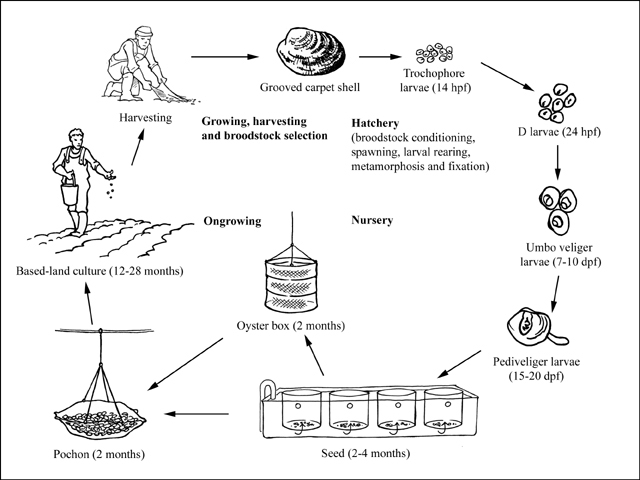

Production cycle

Production cycle of Ruditapes decussatus

Production systems

Seed supply

Farmers obtain seed from their own parks (protected bottoms) or from the natural clam populations in the spring. They dig the clam seed with sand using a small shovel, pass it through a sieve to retain the seed, take it to their Ongrowing parks, and spread it in densities of about 800 clams/m2. They may also dig adult clams from seaport areas and spread them in their parks. Periodically, they have to clean their parks of predators and mud.

Hatchery production

Seed can also be obtained from hatcheries, where breeders, not exceeding 40 mm are maintained for 30-40 days at 20 °C. Breeders are fed with unicellular algae until the induction of the liberation of gametes. Gamete liberation can be induced by raising the temperature from 10 to 26 °C, maintaining it at that temperature for 30 minutes and then reducing it to 15 °C for several minutes; the cycle of raising temperature to 26 °C and lowering it again is then repeated until gametes are liberated. The addition of sperm from a sacrificed animal may also help in liberation. Fertilization occurs in small containers where the animals are isolated from each other. Eggs are filtered through a 40 µm mesh, and transferred to a 10 litre tank, where veliger larvae appear after 48 hours. Larvae are recollected in a 40 µm mesh and reared at densities of 3 000 larvae/litre. They are fed with unicellular algae every day during the first week and then every second day until metamorphosis.

Nursery

Clams can be reared in nurseries within greenhouses, with controlled feeding by using unicellular algae or reared in meshed containers over culture tables. An alternative is to pump environmentally controlled water to inland tanks where clams are placed in cylinders of about 50 cm diameter and 20 cm long, with a bottom made of a rigid mesh.

Ongrowing techniques

Culture techniques are simple, consisting of regular maintenance of the substrate, avoiding algae, starfish and other predators; oxygenating the substrate; and maintaining an appropriate clam density and seeding juvenile clams.

Harvesting techniques

In the Galician region, fishermen harvest clams by walking the intertidal areas and using special hand shovels, or sometimes by using the rakes that are normally used for keeping the culture beds clear of seaweed. Clams may also be harvested from boats, which may vary in size between less than 1 tonne and up to 12 tonnes. Some are propelled with oars, others with outboard engines. Various collection tools are used, including the 'rastro' and the 'raño' (rake), which are operated from the boats with the help of a long handle. The closed season is from March to October, and the minimum size allowed for Ruditapes decussatus is 30 mm. Some Galician areas have protected bottoms called 'parks' for the extensive culture of clams. In hand (walking) harvesting clams are harvested with the help of different types of small shovels; sometimes the rakes that are usually more employed for cleaning the parks of seaweeds are employed.

Handling and processing

Fishermen bring their clams to depuration stations where they are held in tanks for at least 42 hours. The clams are then packed in net bags of 0.5 - 1 and 2 kg, and are destined to be canned or eaten fresh. They are transported by refrigerated trucks which maintain their temperature at 3 - 10 °C; the clams have a shelf life of 5 days. Canned clams are prepared with vinegar and various sauces. In the Galician region, the most popular meal with clams is 'ameixas a marineira' (mariner clams). The clams are opened in salted water and cooked with a special sauce (onions, garlic, parsley, bread grind and white wine).

Production costs

Production costs are greatly influenced by the socio-economic environment and the size of seed supplied. If nursery time starts in spring, harvesting occurs in the late fall or early winter of the following year. Important factors in total costs are seabed leases or exploitation charges hatchery and nursery facility costs, management and harvesting tools and labour.

Diseases and control measures

| DISEASE | AGENT | TYPE | SYNDROME | MEASURES |

| Perkinsosis; Clam Perkinsus disease | Perkinsus olseni; P. atlanticus | Protistan parasite | Visible milky white cysts or nodules on the gills, foot, gut, digestive gland, kidney, gonad & mantle of heavily infected clams; may induce massive mortality | Clams from areas with records of the disease should not be transplanted; reduce density |

| Icosahedrical virus-like disease of carpet shell clams | Icosahedrical-virus-like organism | Virus | Impact on host not specifically described but mortality can be significant | None known |

| Herpes-like virus infection | Herpes-like virus | Virus | Impact on host not specifically described but mortality can be significant | None known |

| Brown ring disease | Vibrio tapetis | Bacterium | Bacteria adhere to surface of periostracal lamina at mantle edge of shell & progressively colonize the resulting secretion causing brown deposit of organic material (conchiolin) adhering to inner surface of shell; normal calcification process disturbed; growth stunted | Clams from areas with records of the disease should not be transplanted; reduce density |

| Larval mycosis | Sirolpidium zoophthorum | Fungus | Affects early veliger to post-metamorphic juveniles up to 400 µm diameter; spreads throughout soft-tissues causing disintegration; sporangia produce tubes that protrude outside shell & release motile zoospores; in heavily infected cultures >90 % of larvae can be killed within two days | None known |

| Haplosporidiosis | Haplosporidium tapetis | Protozoan parasite | Pathogenicity of plasmodial stage minimal in clams but sporulation stage in connective tissue causes important lesions in digestive gland & gills; no mortalities attributed but effect on clams in different environments unknown (related species are highly pathogenic to oysters on east coast of the USA | Clams from areas with records of the disease should not be transplanted; reduce density |

| Red worm disease | Mytilicola intestinalis | Copepod | Negligible or minimal in most cases; may alter morphology of epithelial lining of gut; when present in numbers produces pea-size swelling of rectum; may cause loss of condition | None known |

Ruditapes decussatus is often grown with other bivalves (Venerupis pullastra, Venerupis rhomboideus, Venerupis aurea, Dosinia exoleta and Tellina incarnate). Their main predators are shore crabs (Carcinus maenas); starfish (Asteria rubens and Marthasterias glaciais); gastropods (Natica sp.); and birds (Larus sp). An individual Carcinus maenas (6.5 cm width) can consume 5-6 clams per day.

Suppliers of pathology expertise

The following can provide expertise in this topic:

Dr. Antonio Figueras

Instituto Investigaciones Marinas, CSIC Spanish National Reference Laboratory for Mollusc Diseases

Eduardo Cabello 6

36208 VIGO

Spain

Telephone: +34 986 21 44 62Fax: +34 986 292 762

E-mail: [email protected]

Dr. Isabelle Arzul

IFREMER, Laboratoire de Génétique et Pathologie

BP 133

17390 La Tremblade

France

Telephone: +33 5 46 36 98 43 Fax: +33 5 46 36 37 51

E-mail: [email protected]

Dr. E.M. Burreson

Director for Research and Advisory ServicesVirginia Institute of Marine ScienceCollege of William and Mary

P.O. Box 1346 Gloucester Point

VA 23062

United States of America

Telephone: +1 804 684 7015Fax: +1 804 684 7097

E-mail: [email protected]

Dr. S. Bower

Department of Fisheries and Oceans Pacific Biological Station3190 Hammond Bay Road Nanaimo

British Columbia V9R 5K6

Canada

Telephone: +1 250 756 7077Fax: +1 250 756 7053

E-mail: [email protected]

Dr. Jorge Cáceras Martínez

Instituto de Sanidad Acuícola, A.C.

Calle 9 y Gastelum # 468,13,14. CP. 22800

Ensenada Baja California

Mexico

Telephone: +52 646 1783473 Fax: +52 646 1783473

E-mail: [email protected]

STATISTICS

Production statistics

Global aquaculture production of Ruditapes decussatus

(FAO Fishery statistics)

(FAO Fishery statistics)

Market and trade

The shelf life of the grooved carpet shell is extremely long (several days out of water, depending on environmental conditions), making this species very desirable, and it obtains high prices in the market. These clams are sold in local supermarkets, popular markets, hotels, and restaurants, including those in Madrid and Barcelona. Prices vary according to their abundance in the market. However, as an approximation, in 1985 the price was about EUR 0.60/kg. In 2005, the price for live Ruditapes decussatusin Spain was about EUR 15/kg.

STATUS AND TRENDS

The history of shell fisheries in the Galician region (Spain) shows that molluscs were managed improperly, and various species have been impacted. The first to be depleted was the flat oyster (Ostrea edulis); after that the digging of cockles and clams began, and as Ruditapes decussatus became scarcer, the digging of Venerupis pullastra and V. rhomboideus began. Currently, the populations of the other commercial bivalves are declining. Besides heavy fishing, clams have declined because pollution increased and the seaports and urban areas grew, degrading their habitat.

MAIN ISSUES

The future of the molluscan production in the Galician Region needs to be planned as an integral reorganization programme to include the following aspects:

- Reorganization of the harvesters and the market structure to improve their responsibility and enhance their profits.

- Creation of protected areas for the recovery and growth of the natural populations.

- Creation of a general programme for the treatment of wastewater from the urban and industrial areas.

- Establishment of a permanent project on the population dynamics of the clams, and biological studies, especially to improve genetics.

- Diffusion of a popular programme for the protection and consumption of bivalve molluscs.

- Creation of a special research programme on bivalve molluscan pathology.

Responsible aquaculture practices

No negative effects on other species have been established but responsible aquaculture practices need to be followed (see Main Issues above).

REFERENCES

Bibliography

| Arnaiz, R. & De Coo, A. 1977. Artes de marisqueo usadas en la ria de Arosa. Plan de Explotacion Marisquera de Galicia. Santiago, Galicia, España. 102 pp. |

| Barnabé, G. 1991. Acuicultura. Ed Omega (Barcelona, Spain). 2 vols. 1099 pp. |

| Cáceres-Martínez, J. & Figueras, A. 1997. The mussel, oyster, cockle, clam and pectinid fisheries in Spain. NOAA Technical Report NMFS 129:165-190. NOAA/NMFS, Washington DC., USA. |

| Ferreira, E. P. 1988. Galicia en el comercio maritimo medieval. Fundacion 'Pedro Barrie de la Maza'. Coleccion de Documentos Historicos. 903 pp. |

| Figueras, A. 1956. Moluscos de las playas de la ria de Vigo. I. Ecologia y distribucion. Investigacion Pesquera, 5:51-88. |

| Figueras, A. 1957. Moluscos de las playas de la ria de Vigo. II. crecimiento y reproduccion. Investigacion Pesquera, 7:49-97. |

| Figueras, A., Robledo, J.A. & Novoa, B. 1992. Occurrence of Haplosporidian and Perkinsus-like infections in carpet-shell clams, Ruditapes decussatus (Linnaeus, 1758), of the Ría de Vigo (Galicia, NW Spain). Journal of Shellfish Research, 11(2):377-384. |

| Figueras, A., Robledo, J.A.F. & Novoa, B. 1996. The brown ring disease in clams (Ruditapes decussatus and R. philippinarum) from Spain and Portugal. Relation with parasitism. Journal of Shellfish Research, 15(12):1-6. |

| Navaz y Sanz, J.M. 1942. Estudio de los yacimientos de moluscos comestibles de la ria de Vigo. Instituto Espanol de Oceanografia, 16:74. |

| Novoa, B. & Figueras, A. 2000. Viral like particles associated to mortalities of carpet shell clam (Ruditapes decussatus). Diseases of Aquatic Organisms, 39(29):147-149. |

| Novoa, B., Luque, A. Borrego, J.J. & Figueras, A. 1998. Characterization and infectivity of four bacterial strains isolated from brown ring disease affected clams. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 71:34-41. |

| Novoa, B., Ordás, C. & Figueras, A. 2002. Hypnospores detected by RFTM in clam (Ruditapes decussatus) tissues belong to two different organisms, Perkinsus atlanticus and a Perkinsus-like organisms. Aquaculture, 209:11-18. |

| Ordás, M.C. & Figueras, A. 2001. Histopathology of the infection by Perkinsus atlanticus in three clam species (Ruditapes decussatus, R. philippinarum and R. pullastra) from Galicia (NW Spain). Journal of Shellfish Research, 20(3):1019-1024. |

| Ordás, M.C., Ordás A., Beloso, C. & Figueras, A. 2000. Immune parameters in carpet shell clams naturally infected with Perkinsus atlanticus. Fish and Shellfish Immunology, 10(7):597-609. |

| Vilela, H. 1950. Vida bentonica de Tapes decussatus (L.). Travaux de la Station de Biologie Maritime de Lisbonne, 53:1-114. |