Aloys P. ACHIENG

former Senior Aquaculturist, Lake Basin Development Authority

Kisumu, Kenya

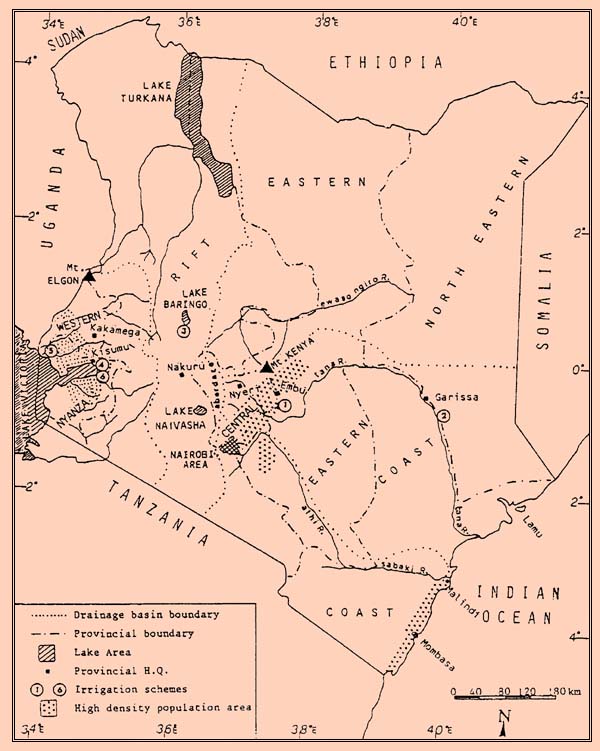

Figure 1. Kenya: Major drainage basins and their water resources, irrigation schemes and highly populated areas

| ASFA | Aquatic Sciences and Fisheries Abstracts |

| BSF | Belgian Survival Fund |

| CEC | Commission of European Communities |

| DDC | District Development Committee |

| DFFC | District fish farming coordinator |

| DoF | Department of Fisheries |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations |

| FFE | Fish farming extensionist |

| FPC | Fish fry production centre |

| GOK | Government of Kenya |

| IOC | Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission |

| KES | Kenyan Shilling (in March 1993, USD 1 = KES 45.60) |

| KMFRI | Kenya Marine and Fisheries Research Institute |

| KVDA | Kerio Valley Development Authority (disbanded after the general election in January 1993) |

| LBDA | Lake Basin Development Authority |

| NGO | Non-Governmental Organization |

| NORAD | Norwegian Agency for International Development |

| SPI | Sessional Paper No.1 of 1986 |

| TARDA | Tana and Athi River Development Authority |

| UNDP | United Nations Development Programme |

| USD | US dollar |

The history of fish farming dates back to 1910 during the colonial era. This came about as a result of the activities of private individuals (European settlers) importing trout through the auspices of the Kenya Angling Association. These new settlers were not familiar with the indigenous Kenyan fish and probably found them difficult to handle or eat. Consequently, for reasons of familiarity, they imported into Kenya trout (Onchorynchus mykiss and Salmo trutta), black bass (Micropterus salmoides) and common carp (Cyprinus carpio). Most of these fish were stocked into various rivers for sport fishing but black bass was stocked also into Lake Naivasha.

The first entry into the fisheries by Kenya Government (GOK) was through the allocation or allotment of a sum of money in the 1926 Estimates, to allow the GOK to undertake the care of trout and trout fishing. From 1926 to 1937, the fisheries programme was administered under the Game Department, by an Assistant Game Warden in charge of fisheries. From 1937 to 1954 the fisheries programme was administered by a Fisheries Warden attached to the Game Department. Finally, in 1954, a separate Department of Fisheries (DoF) was created. In 1948, money was made available for the establishment of a trout hatchery at Kiganjo as ‘part of the fisheries development of the colony’.

At its inception, fisheries development consisted of the stocking and management of trout as a sport fish for the European settlers. Subsequently, an interest was developed in the freshwater commercial fisheries of Lakes Victoria, Baringo and Turkana (Figure 1) and in fish ponds, but major emphasis through the years was on the trout fishery. Only after the Second World War did the GOK show interest in raising indigenous fish, especially tilapias, as potential food crop for the rural population as the target group. The date when scientifically-oriented tilapia culture experiments first started in Kenya is generally regarded to be 1924.

When fish culture extension and rural fish ponds first started is unclear. Ngunjiri, quoted by Balarin (1985), indicates that the national fish culture station at Sagana started in 1924 with research on Oreochromis spilurus niger (ex Tilapia nigra) and that by 1948 fish farming proper had started nation-wide. World Bank (1980a and b) records that the first two fish culture stations in Sagana and Kiganjo were started in 1948, and with them started the interest in rural ponds.

Odero reports that the Kenya Department of Fisheries (DoF) was started in 1954 with a programme of dam and pond stocking in Western Kenya. In the sixties, the DoF launched an ‘Eat More Fish’ campaign and fish farming spread rapidly to various parts of Kenya, including non-fish eating communities in the Central Province.

Most of the ponds were small and many were abandoned. Official estimates suggest over 28 000 fish ponds, ranging from 0.04 to 0.8 ha (Kagai, 1975). Zonneveld (1983) implies that some estimates for the Western and Nyanza Provinces alone indicate over 30 000 ponds. Statistics are confused as no accurate census had been undertaken. Available estimates ranged from 18 000 to 32 000. Most of these ponds were said to be in Nyanza and Western Provinces. In 1981, a French expert, at the request of GOK, arrived in Western Kenya to assess and carry out a survey of the number of ponds, both operational and abandoned (Couteaux, 1981). After a survey lasting several months, the expert reported inter alia, that the number of ponds in the Lake Basin region (Western Kenya) depends entirely on who is talking about them!

To sort out this confusion, the World Bank, at the request of the Government, provided in late 1983 some funds to the Lake Basin Development Authority (LBDA) for a research study and inventory of fish ponds in the Lake Basin region. Fifty-four technicians were involved in the survey, led by a team of three experts - two from FAO and one fisheries specialist provided by the GOK. After a study lasting six months, it was found that there were in fact only 4 842 fish ponds in the whole of Western Kenya.

Since then, LBDA has continually monitored newly constructed and abandoned fish ponds and currently the number of functional fish ponds in the LBDA region is 6 738.

Figure 2. Potential fish farming zones and planned fishery centres

(Modified from Coche and Balarin, 1982)

Farmed fish in Kenya are primarily produced by a few thousand farmers who practice fish farming as one of the many other farming activities. Because the input used are virtually the same as in their farming activities, small-scale fish farming is properly seen in the context of agricultural production. Although at the national level the contribution of fish farming to fish production may be insignificant, at the farmer's level it can have important effects on nutrition and income. Most production from small farmers' ponds is consumed locally, and that which is sold has a high value, KES 40/kg. Fish farming can be practiced in most farming areas (Figure 2, Table 1), bringing fish closer to the rural consumer, who has little hope of eating his share of the national fishery output, which comes primarily from Lake Victoria.

Table 1

Characteristics of the potential fish-farming zones

(modified from Coche and Balarin, 1982)

| Zone (percentage of total area) | Common mean air temperature range (°C) | Fish species | System | Comment 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A (3.2%) Highlands | 5–22 | Trout | Tanks Cages Ponds | Good for trout production all year round. Caution essential during summer as high temperatures may be lethal. |

| B (11.6%) Central Province and Rift Valley | 10–26 | Trout | Ponds Cages | Production of coldwater fish restricted to the winter period: three to six months per year. |

| Carps | Any | Production potential all year round. | ||

| Tilapia | Ponds Cages | Very marginal zone for warmwater fish as cold season limits growth for three to six months per year. | ||

| C (51.9%) Plains and Northern Province | 15–30 | Carps | Any | Very good for carps if seed available. |

| Tilapia | Ponds Cages | Adaptive for intensification of warmwater fish with a possible two-to-three-month non-growing period. | ||

| Catfish | Ponds | Good if seed available. | ||

| D (33.3%) Coastal and Lakeshore Belts | 22–34 | Carps Catfish Freshwater prawns Shrimps | Ponds Tanks Cages | Very good conditions for the culture of all warmwater fish species in both fresh and salt water. Ideally suited to intensive systems with all-year-round production potential. |

1 Subject to local water availability

It is unlikely that the catch rates from the major lakes will increase much beyond the current production. The lakes are already showing some signs of qualitative overfishing where large individuals of most species are beginning to disappear from the catches. Consequently, the gap between national fish requirement and national fish production can only be met through fish farming. Import of fish as an alternative would be too expensive. This lays emphasis on the urgent need to develop fish farming to increase fish production. Increase in fish production through fish farming is contingent on a variety of factors, the most important of which are financial investment, technical expertise, production inputs and support services.

There is a diverse indigenous and exotic fish fauna in Kenya. Balarin (1985) chronicles culture trials which have been undertaken with many freshwater and marine species. Warmwater species currently cultivated include tilapias (Oreochromis niloticus, O. mossambicus, Tilapia rendalli, T. zillii), common and mirror carp (Cyprinus carpio), and black bass (Micropterus salmoides). Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) and, to a lesser extent, brown trout (S. trutta), are cultured in cold-water areas. Marine shrimp (Penaeus indicus and P. monodon) are cultured on the coast. Locally occuring or introduced species with potential for culture include the catfish (Clarias spp.), milkfish, mullet, Labeo and Barbus spp.

There is a wide range of practices in Kenya. Extensive small-holder fish farming consists of one or more earthen ponds of 130 to 1 000-m2 area, each stocked with varying amounts of tilapias (in Western Kenya) or tilapias and carp (in Central Kenya). Water may be stagnant or flowing through. On-farm organic fertilizers and sometimes feeds are applied at varying rates. Fish are cropped periodically by net or trap, and occasionally all fish are removed by drainage and the pond restocked. Productivity is in the order of 500 – 2 000 kg/ha/year. Fish are consumed by the farmer and his family and some are sold at the pond side. Problems commonly encountered are poor pond siting and poor construction, leading to loss of water through dike breakage or drying and flooding; insufficient quality and quantity of fingerlings; loss of fish due to predators and thefts; and on-farm limited use of costly fertilizers and feeds.

Tilapia seed is produced at the DoF Sagana Fish Farm in Central Kenya, at LBDA fry production centres (FPC) in Western Kenya, at various smaller DoF fry centres, and by small-scale fish farmers themselves. Sagana is the largest centre but currently produces only about 1 000 fingerlings of mixed tilapia species per month. Nationally, farmers still provide the majority of tilapia fingerlings, and there is effective quality control only at the LBDA FPCs. Some carp fingerlings are produced by Sagana, District Fisheries Offices and Meru farms, as well as a few private farmers, but the demand still exceeds the supply.

There are three functioning commercial trout farms on the slopes of Mount Kenya, two operated by Tamarind Trout Farm Ltd and one by Kentrout Ltd. These vertically integrated companies have been in operation since the mid seventies. They have a combined production capacity of 48 t/yr but currently produce only about 23 t/year due to shortage of fingerlings. They use only rainbow trout. There are a few (e.g three in the Nyandarua District) small-scale individual trout farmers who have received assistance from the commercial farms and DoF, and a school-based farm in Meru District. Trout farming requires clean, clear, cold (10–18°C), flowing water in large quantities which severely restricts its range or practice in Kenya. It also entails high investment and operating costs and pond management practices.

The operating commercial farms have their own hatcheries where both locally produced and imported eggs are hatched. Trout are grown in flow-through circular tanks or raceways, fed a company- made high protein feed and harvested after 8–10 months. Prices are set by the farms who sell directly to restaurants and retailers in urban tourist areas. About 17 per cent of Tamarind's and all of Kentrout's current production (60 kg/week for each company) is sold to company-owned restaurants. About 5 per cent of the production is sold in smoked form. Managers at both farms indicated that there is a large unmet demand for trout, but no formal market survey has been carried out. Common problems encountered include difficulties in getting trout to breed locally; insufficient number of imported eggs to make up the difference; high cost of fingerlings purchased from one another's hatchery or DoF Kiganjo; poor water quality and insufficient water supplies during the dry season. Local technical know-how, feeds and diseases are not considered problem areas.

Small farmers cannot afford to operate vertically integrated trout farms and must purchase all farm inputs, which increases costs. They also encounter difficulties in delivering the fish to market and in some cases sell to existing commercial companies below market price, reducing profit margins. There have been a number of financial failures in this sector.

During the eighties, DoF, assisted by UNDP/FAO tested and demonstrated the feasibility of the extensive culture of Penaeus indicus and the intensive culture of P. monodon at the Ngomeni Fish Farm near Malindi. However, a survey of possible shrimp farming sites showed limited potential due to competition from lucrative salt evaporators, mangrove forest conservation, and the holding of land by owners for speculative non-productive purposes. Three private proposals for shrimp farms made in 1987 could not attract financing, and DoF has recently leased the Ngomeni Fish Farm to a private operator. It has been suggested that for this sector to develop, technicians must be trained, mangrove or salt works areas be made available, and export compensation granted.

A number of private and public small reservoirs in Central Kenya have been stocked with carp, tilapia and black bass. Reservoir sizes vary from 0.5 ha to 120 km2 (Masinga Dam), although most are less than 100 ha. The resulting fisheries are managed by the owner or local groups under county council licence. Harvesting is by gillnets or seine nets and fish are sold locally or marketed in urban areas.

Since the early eighties, the government of Kenya has put more emphasis on fish production from the natural waters of the country, in order to meet local demands of a fast growing population. The need to produce more fish as a source of animal protein is even more pressing in Western Kenya where 40 per cent of the country's total population live, although the region consists of only 8 per cent of the total area of the country. Since the catches from major lakes are in general approaching the maximum level of potential yield, increases in production through fish culture offer a promising alternative.

In 1979, the GOK established the Lake Basin Development Authority (LBDA) with HOs based in Kisumu (Western Province), with responsibility for the overall planning, coordination and implementation of programmes aimed at accelerating rural development and improved food production. In 1982, a UNDP/FAO Preparatory Assistance Mission (Coche and Balarin, 1982) reviewed the fisheries and aquaculture situation in that region. The mission concluded that there was an immediate need for more rapid and intense assistance for the development of rural small-scale fish farming in the Lake Basin region. The rehabilitation of several thousands rural fish ponds which had been constructed and then abandoned over the last 30 years, was emphasized. Furthermore, sustained and effective fish-culture extension services were needed to support and improve production by rural farmers. Subsequently, the Belgian Survival Fund (BSF) provided major financial contribution to FAO to supplement initial UNDP inputs.

A project proposal was prepared and submitted for financing to UNDP with the objectives of rehabilitating some 2 000 existing rural fish ponds and increasing their actual production, as well as setting up a specialized fish-culture extension service together with associated support facilities such as bicycles and motorbikes for mobility. Fish Fry Production Centres (FPC) were also planned - one for each of the seven districts in the region. However, the main phase of this UNDP/FAO/BSF project KEN/80/006, Development of Small Scale Fish Farming in the Lake Basin, could not commence before 1984. At the request of the Government, FAO/TCP provided initial financial assistance in 1983, in order to give specialized training to a team of some 54 fish farming extensionists and their supervisors.

Fish farming extension is carried out by DoF Fisheries Assistants and Fish Scouts as well as by Fish Farming Extensionists (FFE) in the LBDA area. DoF personnel operates on foot or by public transport. In the LBDA area, the FFE operate by bicycles and ten of their supervisors are provided with motorcycles. The supervisors are based one at each District HQs, in each of the 10 Districts in Nyanza and Western Provinces. In-service refreshing courses of one week are organized once a year for all the extension agents and their supervisors. Lecturers are drawn from among the senior staff of DoF, LBDA and Kenya Marine and Fisheries Research Institute (KMFRI). Courses are also organized for progressive farmers at the rate of 450 fish farmers per year, taking 45 at a time from each of the 10 districts. These courses are short and last three days only, divided into two classroom lectures and one day for practical work. Lecturers are LBDA staff and senior extension agents. DoF also organizes regular courses for scouts and fisheries assistants at the Naivasha Wildlife and Fisheries Training Institute.

The success of aquaculture extension services around the world mostly depends on educated people who are dedicated to helping their country develop. These people, whether or not Government employees, should be willing to live and work under difficult conditions, training farmers in the techniques of fish farming. At the local level, these extension workers are the key to the growth of aquaculture in the country, for they are the people who are responsible for introducing aquaculture where it did not exist and for improving on the traditional methods.

Government funds for fish demonstration ponds are obtained from District Development Committees (DDC) as grants originating through the office of the Ministry of Finance and Planning.

In 1980–82, about KES 1.73 million were made available for the establishment of 32 DDC ponds (Coche and Balarin, 1982). Private funds have also been used to a large extent and most of the large scale commercial farms are privately owned. Kenya has received a large number of bilateral and multilateral aid funds to assist aquaculture and fisheries development. Major aid agencies have included the World Bank, NORAD, UNDP, FAO, CEC and Belgium.

The success of large scale fish farming is, in addition to its bio-technical feasibility, dependent on a market for fresh fish at an acceptable price and on marketing infrastructure. Therefore, the market demand and existing marketing channels for tilapia have been studied in the LBDA region, Western Kenya (Tables 2 and 3, and Figure 3). Tilapias are among the highest valued fish in Kenya (Zonneveld, 1985) and fetch the highest price of all species on the market. In areas around the lake, fresh fish is preferred, but in distant areas where fresh fish is scarce due to the distribution and preservation problems, processed fish (sun-dried, smoked and fried) is readily acceptable.

A number of consumers were interviewed in Bungoma, Mumias, Webuye, Sudi, Eldoret, Matunda, Kitale and Busia. These markets are situated at quite a distance from Lake Victoria, where fresh fish is scarce. The emphasis was on whether these people appreciated or ate fish and, if so, what type of fish. In 80 per cent of the cases the respondents were asked whether they had fresh fish on their menu and if so what type of fish. Fifty-two per cent of the respondents named tilapia, but quite often it was not available because of the limited supply. In 48 per cent of the cases tilapia was not on the menu, but 86 per cent of these hotels and restaurants would put it on the menu if it was readily available. From the observations it may be concluded that the demand for tilapia is high in the LBDA region, and that the present supply is not enough to meet this high demand (Tables 2 and 3).

|

|

Figure 3. Fishermen's cooperatives and main marketing channels of fish in the LBDA area

Table 2

Consumer market survey for tilapias in the LBDA area (1985)

| District/Town | Number of persons interviewed | Eat or appreciate fresh tilapia | Do not eat or do not appreciate fresh tilapia | Percentage of total sample who prefer tilapia |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bungoma | ||||

| Bungoma | 55 | 40 | 15 | 73 |

| Webuye | 30 | 25 | 5 | 83 |

| Sudi | 20 | 14 | 6 | 70 |

| Uasin Gishu | ||||

| Eldoret | 60 | 55 | 5 | 92 |

| Matunda | 10 | 9 | 1 | 90 |

| Trans Nzoia | ||||

| Kitale | 40 | 31 | 9 | 77 |

| Kakamega | ||||

| Mumias | 15 | 10 | 5 | 67 |

| Total | 230 | 184 | 46 | 80 |

Table 3

Number of hotels and restaurants that serve or would like to serve tilapia

(Survey in the LBDA area, 1985)

| District/Town | Number | Serve tilapia | Would serve, if available | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||

| Bungoma | ||||

| Bungoma | 5 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| Webuye | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| Kakamega | ||||

| Kakamega | 5 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| Mumias | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Uasin Gishu | ||||

| Eldoret | 10 | 4 | 6 | 4 |

| Trans Nzoia | ||||

| Kitale | 5 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| South Nyanza | ||||

| Homa Bay | 5 | 5 | - | - |

| Migori | 5 | 3 | 2 | |

| Kisii | ||||

| Kisii | 6 | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| Total | 46 | 24 | 22 | 19 |

The responsibility for fisheries development rests with the DoF in the Ministry of Tourism and Wildlife. Other ministries are responsible for activities related to fisheries such as, for example, the Ministry of Cooperative Development (fishermen cooperatives), the Ministry of Public Works (access roads), the Ministry of Science and Technology (research institutes) and the Ministry of Regional Development (regional authorities - LBDA, TARDA, Coast Development Authority, Ewaso Nyiro North and Ewaso Nyiro South Development Authorities).

DoF is responsible for the administration and development of fisheries and aquaculture, enforcement of fisheries regulations including licencing, collection and reporting of fishery statistics, market surveys and quality control, as well as the control of export and import of fish and fishery products. It is organized on a geographical rather than a functional basis with four Assistant Directors responsible for Western, Rift Valley, Central and Coast Regions. There is no office in the Department responsible for aquaculture. The main unit of activity is the Fisheries Station or the District Fisheries Office which reports to the Director responsible for each region. At present there are 50 fisheries stations in the whole country. DoF with HQs in Nairobi has about 180 Fisheries Officers, most of whom are graduates trained in fisheries-related fields and have been posted to man various fisheries stations in the country. They are supported by about 1 000 junior staff - Fisheries Assistants and Fish Scouts. While DoF is responsible for administration and development of fisheries, KMFRI is charged with providing the scientific basis for the management of Kenya's aquatic resources and the preservation of the aquatic environment.

Regional Authorities working in collaboration with DoF and other ministries have direct charge over development within their defined geographical areas and operate fish farming development projects. Their reports on fish farming development are generally for internal use. LBDA HQs in Kisumu has a total of seven senior professional staff supported by two diploma officers trained at the UNDP/FAO African Regional Aquaculture Centre (Nigeria), 18 high-school-level staff trained in Israel and 70 FFE trained locally. TARDA has eight fisheries staff who assist with the fisheries exploitation of the large reservoirs on the River Tana. Carp, which originally escaped from the Sagana Fish Farm, is the main fish harvested from Masinga Dam.

Fisheries and aquaculture training is given in the Naivasha Wildlife and Fisheries Training Institute. The institute was built with a World Bank loan and has very good physical facilities. The institute offers basic courses for game rangers and fish scouts, certificate courses for fisheries officers and assistant game wardens. The institute has proposed to run a diploma course in fisheries management and aquaculture (DIGMAQ), but this proposal has not been implemented so far. The syllabi of both the certificates and diploma courses in fisheries management, include aquaculture as one of about ten subjects covered.

While the institute has good physical facilities at the main campus, the fisheries complex off the main campus is not yet developed. The laboratories and library have very few books on fisheries and aquaculture matters. The personnel available do not have adequate qualifications for running a full fisheries programme. The courses include classroom instruction on fish farming but no practical work.

There is no other training facilities in fisheries at all levels.

LBDA professional officers receive in-house and overseas training. LBDA holds annual refresher courses for its extension staff. These courses address specific topics relevant to current fish farming development activities. Training syllabi and material are developed by LBDA staff and the courses have a heavy practical orientation. Some of the DoF staff in Western Kenya have also attended these courses.

LBDA organizes periodic three-day training courses for farmers covering improved fish farming techniques. Farmers training centres, private farmers' ponds and FPC are utilised for practical work.

Kenya has six universities, all with capabilities to carry out research and teaching related to aquaculture. But, apart from Moi University, and to a certain extent, Nairobi University, there are few members of staff competent enough to teach aquaculture programmes at university level.

Kenya has undertaken systematic development planning at the macro-economic level since ‘Uhuru’ in 1963, a period of nearly 30 years. Whereas the broad goals of development have remained the same, there have been shifts of emphasis over the years. In 1965, the government published a Sessional Paper entitled ‘African socialism and its application to planning in Kenya’, which outlined the basic objectives for independent Kenya and the ways in which it was proposed to achieve them.

These objectives included individual freedom (freedom from want, disease, ignorance and exploitation; expansion of the economy, with equitable sharing of benefits) and integration of the national economy. Four basic principles were also employed: widespread participation in the development process by all Kenyans; diversity of organizations forms and incentives (governmental, parastatal, co-operative, private and voluntary); a decisive and leading role for the government in initiating and directing development, and mutual social responsibility exemplified by the Harambee or self-help movement.

Kenya has always possessed a mixed economy, with a high priority placed on agricultural development (more than 70 per cent of the population of working age is employed in agricultural activities). In the case of industry, however, there has been variations in the approach, with early emphasis on import substitution and infant-industry protection being later replaced by a policy of exposing industry to increased international competition, coupled with encouragement of diversification into non-traditional exports.

There has been a tendency to move away from reliance upon interventionists solutions and state initiatives. Most notably, comprehensive price controls, introduced in the early seventies as a result of a high level of inflation, have proved problematic and have resulted in questionable economic benefits. The 1974–79 and 1979–83 plans saw a progressive shift away from such measures except for selected basic items. However, emphasis on Harambee and the promotion of co-operatives has been sustained throughout the post-independent era.

The theme of the 1984–88 plan was to ‘mobilize domestic resources for equitable development’, a reflection of concern over equitable distribution of the fruits of development in regional terms. This plan also showed concern over the growing debt service problem. As part of the regional theme, the plan introduced a new emphasis on grass-root development: the District Focus for Rural Development which was accompanied by changes in development planning procedures. Responsibility for planning and implementation of rural development was shifted away from the headquarters of ministries to the districts. Whereas responsibility for general policy and the planning of multi-district and national programmes became the task of District Development Committees (DDC), chaired by District Commissioners but including a wide spectrum of representatives from within the district community.

The most fundamental review of macro-economic policy occured in 1986 with the publication of Sessional Paper No.1 of 1986 (SPI, 1986). It continues to be used as the principal inspiration and touchstone for all economic policy making, providing the guidelines for the most recent plan, 1989–93.

The tone of this SPI was sombre. While the language recalled previous plans and policy statements, the paper focused particularly on what it calls the ‘stark realities’. It is worth quoting in full the opening statement of the SPI:

‘At the end of this century, Kenya will have a population of about 35 million people, 78 per cent more than lived in Kenya in 1984. The population will include a workforce of 14 million people, 6.5 million more than in 1984. These future workers have already been born. To accomodate that workforce without a rise in the rate of unemployment, it will be necessary in the next 15 years almost to double the number of jobs in Kenya. 9 to 10 million by 2000, over one-fourth the total population, compared to only 3 million (15%) in 1984. Unless new workers can be attracted in large numbers to jobs in smaller urban centres and on prosperous farms, it will be necessary to build at least six cities the size of present day Nairobi, to watch Mombasa and Nairobi expand into cities of two to four million each. And, unless those working on farms and in rural towns continue to raise their productivity, the rural population will be plagued by uneconomic subdivision of land, migration into marginal areas, falling average incomes and food shortages’.

Accordinlgy, the SPI proposed a new emphasis in development priorities characterised by a push for ‘Renewed, rapid, economic growth’. It stated it was imperative that:

Direct reference to the role of the Fishing Sector was absent in the SPI of 1986. It did, however, contain a number of more specific points of concern. Some of these were macro-economic in nature, others related to agriculture, with which fisheries is closely interrelated. Additionally, there were some important spatial considerations relating to the rural-urban balance and interregional priorities.

In terms of specific targets for growth rates in Gross Domestic Product, the SPI of 1986 was ambitious. The targets were pitched to ensure that economic growth would outstrip population growth by a margin sufficient to produce rising per capita real incomes. The target for 1984–1988 was 4.8 per cent per year and for 1988–2000 it was 5.9 per cent per year. These targets may be interpreted as approximating to a target growth of about 5 per cent per year, in broad terms. The 1990 Economic Survey reports attained growth in GDP in 1988 and 1989 of 5.2 and 5 per cent respectively.

In more qualitative terms, the SPI 1986 stressed the need for budget rationalization. This included spending proportionately more on immediately productive services. That is to say, more should be spent on infrastructure (especially in smaller towns and rural areas), on programmes to raise agricultural production, as well as on vocational and technical education, health and other basic needs. There should also be a process of budget rationalization aimed at more rigorous control of projects, cost recovery and a major drive to reduce the burden imposed by development projects on recurrent public sector expenditures.

An expanded role for the private sector was also foreseen. The SPI stressed that ‘… on the basis of sheer size and coverage alone, the private sector must play a dominant role in revitalizing Kenya's economy’.

The SPI 1986 stressed the need to reduce the disproportionate share of salaries in government expenditure which, in ten years, grew from 47 to 60 per cent of ministries' recurrent outlays. In some areas, such as the agricultural extension service, salaries were, at the time of writing of the SPI, in excess of 90 per cent. To reduce what it described as the ‘unsustainable growth in the Civil Service’, a fundamental change of attitude to public service employment was proposed including greater emphasis on promotion by merit and achievement, no guaranteed employment for new graduates in the government and a redeployment of personnel consistent with the District Focus for Development.

Finally, the SPI 1986 proposed a set of policy measures aimed at enabling the private sector, especially the informal private sector, to obtain credit. Proposals included lower collateral requirements, encouragement to aid donors to provide low interest loans to commercial banks to cover higher risks of lending to the informal sector, encouragement of credit arrangements through NGOs and Co-operatives, favouring of small firms in government tendering regulations, restructuring of the Joint Loan Board Scheme, and strengthening of District Trade Offices' extension services.

Since independence, the availability of food items has grown, broadly in parallel with popultation growth, although Kenya still imports some food items. Following the 1979–80 drought, the government policy has aimed at self-sufficiency in most food production through provision of incentives to farmers and avoidance of subsidies to consumers.

A major concern of the SPI 1986 was to address the problem of how to feed the projected population of 35 million by 2000, of a doubling of the labour force and of a tripling of the urban population. It was stressed that self-sufficency was required for all major commodities, except wheat, vegetable oil and rice. Thus, food output would have to rise without encroaching on the area under high value crops and food production per area of land of specified potential would need to increase substantially through higher yields. The value of output per additional unit of labour, as well as per unit of land, would also need to increase.

The paper stated that therefore there required to be a major effort to intensify agricultural production. Several strategies were mentioned including increased intensity of application of existing techniques, raising the genetic potential of crops through the introduction of new varieties (especially of maize and other grains) and diversification into higher value activities, coupled with a focus on major crops with a high income-high employment per hectare, such as tea, coffee and horticultural crops, the latter contributing to export diversification.

The disturbing future urban scenario painted in the opening paragraph of the SPI 1986 (quoted above) requires that development takes place at least as vigorously in rural areas as in urban ones. The main objectives set by the SPI 1986 were:

to avoid excessive concentration of Kenya's population in the largest cities;

to promote vigorous growth of secondary towns and smaller urban settlements;

to foster productive linkages between agriculture and other sectors, between rural areas and local service centres between market towns and secondary cities; and

to bring renewed economic growth to all regions so that even the least developed ones can share in the general growth of the economy.

The development authorities such as LBDA, the TARDA and the Kerio Valley Development Authority (KVDA) were set up inter alia to address the problems of the relatively less developed and disadvantaged regions of Kenya. It is relevant to note that the LBDA region which produces over 90 per cent of Kenya's fish, is also an area with lower average per capita incomes and with a higher incidence of malnutrition. LBDA reports that the Gross Regional Domestic Product per capita in its region is only 59 per cent of the national average for Kenya. The same picture emerges from statistics of morbidity reported by the Ministry of Health: morbidity rates per 100 000 from malnutrition as high as 1 623 in the Nyanza Province, 1 207 in the Western Province and 1 665 in the Coast Province. All other provinces have rates below the Kenyan average of 1 001. These three most disadvantaged provinces are also the main fish-producing areas.

This review of government thinking on economic, social and regional aspects of development suggests a number of immediate implications for the planning of the fisheries sector. These may be summarized as follows:

The primary concern must be the generation of wealth. Fisheries represent a primary source of rural wealth and, as such, a reason for men and women to remain in rural areas and not to migrate to the overcrowded cities. Fisheries can be an engine of growth and produce multiplier effects on other sectors such as housing, transport and commerce. Such productivity must be sustainable and within the capacity of fish resources and, where it takes a capital-intensive form, should not be damaging to the welfare of small-scale producers.

Fisheries should be seen primarily as a source of wealth in those areas where availability and traditional utilization of fish are likely to facilitate the development process. Now that the successful policies of the past aimed at increasing the wider national awareness of fish as a valuable food have served their purpose, there is little case for further ‘across the board’ efforts to promote fish consumption everywhere. The private sector and market forces should be relied upon to link effective demand with willing suppliers. Where state intervention is deemed necessary, it should be targeted at stimulating wealth generation in the vicinity of the fishery. Efforts to increase fish availability in rural areas remote from the sea, lakes or rivers, through development of fish farming or stocking of reservoirs (culture based fisheries) should be encouraged, provided they generate significant wealth-added value in the economy.

Whilst the fishery sector is broadly complementary to agriculture as a food production sector, it should also be recognized that this involves an element of competition: fish farming in particular utilizes agricultural inputs such as rural labour, land and water, fertilizers and feeds. The priority given to intensification and diversification of agriculture makes it imperative that fish farming development priorities harmonize with agricultural objectives, recognizing that small-scale fish producers are farmers who farm fish in addition to other crops. Successful fish farming systems will be those which optimize the use of inputs within the total farm context.

The private sector is seen as having the dominant role in fisheries development at both artisanal and industrial (or semi-industrial) levels. The efforts of the government should, therefore, be aimed at facilitating and creating a favourable business environment for private sector initiatives provided of course that there are adequate safeguards with respect to economic, social, fiscal and bio-physical considerations.

By the way of a background to the sections which follow, and which lead towards the formulation of a contemporary development plan for Kenya fisheries, this section reviews past plans for the sector as described in the sequence of Five-Year Development Plans.

The fisheries sector has had a long struggle to receive due recognition of its economic importance, often given only passing attention, sometimes as little more than a footnote to other sectors such as agriculture or wildlife. For example, fish is mentioned only briefly in the SPI 1986 as ‘beef and other meats’.

A review of the six development plans reveals the difficulties that the Department of Fisheries has experienced in determining the potential of Kenya's fisheries and in attracting the funds needed to embark on systematic development.

At first sight, the performance of the fisheries sector has been excellent. From fish production levels of around 20 000 t in 1964, the output is now reported at around 145 600 t (1989). Estimated per capita consumption of 2.32 kg per year in 1964 is now put at about 5.3 kg, during a period when population has grown from 9 million in 1964 to around 23 million in 1988.

There may be grounds for believing that actual production is somewhat lower than the official figures currently indicated, but it is undeniable that there has been remarkable growth in production. If, however, the expectations and projections shown in various development plans are compared with the out-turn, then the difficulties of projecting and planning for fisheries are evident.

The First Plan (1964–70)

The First Development Plan complained about the reduction of fishing yields on Lake Victoria from 20 000 t in 1957 to only 11 000 t in 1962 as a result of ‘many years of overfishing’, and highlighted the potential of the other lakes, especially Lake Rudolf (now Lake Turkana), and of coastal fisheries.

The 1966–70 Plan (regarded officially as the First Development Plan), which swiftly followed the 1964–70 plan, continued in the same vein, describing Lake Turkana as having ‘the largest untapped potential of any inland fishery in Kenya’. These early plans contained themes which have become perennial in fisheries development plans in Kenya but which have seldom been rewarded by investment of resources commensurate with the Fisheries Department’ aspirations. Themes include market improvements, shore preservation and storage facilities serving fish production areas, mechanization of small boats, harbour and landing place improvements, improved roads to fishing villages, development of the deep-sea fishery (including a cannery, industrial vessels and fish meal plants) and training.

The 1966–70 Plan also drew attention to the undoubted handicap of the Fisheries Department inherited from colonial days: ‘In the past the Fisheries Department has dealt primarily with the Sports Fishery. This emphasis has now, however, been shifted towards commercial fisheries’. At independence it should be noted, the Department possessed only four professional staff.

The Second Plan (1970–74)

The seventies saw a recognition of the role fisheries could play in improving dietary standards. An ‘Eat More Fish’ campaign was mounted aimed at the one half of the Kenyan population who are not traditional fish eaters. Again, the hopes for additional fish production centred on two main areas: coastal marine fisheries and Lake Turkana. The target increases were published with an overall increase from 30 000 t in 1968 to 55 000 t by the end of the Second Plan period (1974). Fish farming was also seen as a means of improving nutritional standards in the rural areas. Major investments in industrial vessels for exploiting the offshore tuna and sardinella resources and for shrimp trawling were also proposed at this time.

The Third Plan (1974–78)

The Third Plan acknowledged the failure to meet the 55 000 t target of the previous plan, which was attributed variously to overfishing on Lake Victoria and Lake Naivasha and silting in Lake Baringo. But it contained detailed targets for higher production, this time to a more modest target of 35 000 t (27 000 t inland and 8 000 t marine). However, the higher landings during the previous period were noted with satisfaction, having risen from 28 000 t in 1966 to nearly 30 000 t in 1972. Lake Turkana's contribution more than doubled during the same period.

The Fourth Plan (1979–83)

The Fourth Plan reported further increases in landings, the 35 000 t target having been surpassed - estimates for 1976 were quoted as 41 260 t. The growth, however, came from Lake Turkana, with landings reported almost at the same level as Lake Victoria: 17 044 t for Lake Turkana in 1976, as compared to 18 680 t for Lake Victoria. Marine landings were stable at around 4 000 t. This Fourth Plan returned to some of the familiar themes of the 1966–70 Plan. The main thrust of the fisheries development strategy, as stated, was

The projections of the Fourth Plan showed marine catches more than doubling by 1983 to 10 800 t, most of the increase coming from the proposed new trawlers. Inland fisheries were assumed to show a modest annual growth of 3.8 per cent, with no significant shifts in the relative contributions of the individual lakes, but with a major contribution from fish farming, forecast to rise from 275 t in 1976 to 1 800 t by 1983. The overall fish production projection for 1983 was 59 000 t.

It was during the period covered by the Fourth Plan that dramatic changes took place in Kenyan fisheries, surprising fishermen, biologists and administrators alike. This was the population explosion of the Nile perch(Lates niloticus), a voracious predator species, which had been introduced officially into Lake Victoria from Lake Albert in Uganda and Lake Turkana in Kenya in 1962–63. As a result of this population explosion, and according to the Department of Fisheries statistics, the Lake Victoria landings of Nile perch in Kenya increased from around 1 000 t in 1978 to over 50 000 t by 1983. Between 1977 and 1985, overall landings quadrupled. Why this should have happened and which would be the long-term implications have since been the subjects of intense debates among scientists.

By the end of the decade, landings in Kenya from Lake Victoria were reported at 135 400 t (approximately half of which was Nile perch). However, it should be noted that another introduced species, Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus), had also shown remarkable growth, doubling during the second half of the decade to reach 13 per cent of landings. The indigenous species Rastrineobola argentae, known locally as ‘omena’ or ‘dagaa’, had also quadrupled during the course of the eighties. Other indigenous species had, in the main, declined both proportionately and in absolute terms.

The Fifth Plan (1984–88)

Apart from reflecting obvious satisfaction with the early evidence of rapid growth in fish production from Lake Victoria, the Fifth Development Plan dealt little with fisheries development, compared with its predecessors. There was no discussion within it about the lack of development of a trawler fleet, although reference was made to a proposed cannery to be constructed at Mombasa. Prominence was given to aquaculture, including the coastal shrimp farming project for export, projected to produce 6 000 t by 1988. Finally, the establishment of a Fisheries Development Authority was proposed.

The Sixth Plan (1989–93)

The Sixth Development Plan is also brief in its treatment of the fisheries sector. The growth in overall production is noted, calculated at about 14 per cent in compound terms between 1980 and 1988. The decline in production of certain lakes (Turkana, Naivasha and Baringo) is also noted and attributed mainly to ecological changes due to climatic variations and over-exploitation. Lake Turkana, in particular, suffered a fall in water level caused by a reduction in supply from the Ethiopian River Omo, which flows into it at the northern end.

As before, the document does not relate the proposals of previous plans with the out-turn. This is presumably because the projects and proposals either were not implemented through lack of funds, or change of policy (e.g. deep sea vessels and trawlers on Lake Victoria), or failed to live up to expectations (e.g shrimp farming). However, the perennial concerns were once again raised: the need for elimination of bad fishing methods, for introduction of better gear, for better shore facilities for storage and distribution, for better access roads and credit facilities.

The Sixth Plan also contains projections of fish production for the major lakes and three categories of marine products (fish, crustacea and ‘other’). Growth (with only minor variations between the categories), is projected to be a little over 4 per cent in real terms for all categories. The implication of these projections is that landings from Lake Victoria would reach nearly 150 000 t by 1993.

Finally, the Sixth Plan refers to the promise of high potential from the Kenyan exclusive economic zone (EEZ) in the Indian Ocean. The strategy for its development is, however, to be tackled within the plan period and the plan itself does not contain any specific proposals.

As the Fourth Plan points out, the scope of the government's influence is limited:

‘Government involvement in fisheries activities … can only provide extension, research and limited development services to the fishing community and foster an economic environment which will provide the incentives to expand output’.

Learning from the past experience, it is clear that actions which are proposed in the future must be accompanied by their rationale, and a clear distinction has to be drawn between what the government can influence, what it cannot and the extent to which the use of policy instruments can bring about development.

Fish culture development in Kenya has been assessed by a series of evaluation missions sent by the donors. These assessments have been carried out by the missions indicated below.

A number of reasons for past failures in aquaculture development were summarized as follows by Coche and Balarin (1982), not necessarily in order of importance:

inadequate recurrent budget support resulting, for example, in reduced extension staff mobility and reduced staffing;

fish culture research of little practical importance, not providing the necessary information for extension support;

wrong fish species selection particularly in cooler regions, unsuitable for warmwater fish culture development; even in suitable areas, selection of a slow growing species such as T. zillii;

introduction of fish farming into regions where fish is not traditionally part of the diet, without a strong, long-term commitment to development;

wrong approach to rural development: free distribution of fingerlings, association of law enforcement to extension, individual initiatives undeveloped;

lack of adequate support to fish farming development resulting in bad site selection (acid soils, inadequate water supply), bad farm design (faulty water supply), bad construction records (excessive cost, lack of bank slopes), and bad pond management (stocking rates, organic fertilization, feeding, length of rearing period);

pond sites difficult to access (deep valleys) and very dispersed;

lack of properly trained personnel, both cadre staff and extension workers;

instability of staff due to frequent rotations, resulting in discontinued programmes and efforts;

lack of collaboration and coordination between planning, research, and management staff, impairing the flow of information.

Problems in the commercial sector are similar and the following may be added:

limited capital for investment or a reluctance to invest large sums in areas yet untested and still uncertain as a business likely to guarantee returns;

absence of government technical support and reluctance to pay for professional advice, and

research pilot phase often too short to provide valid economic data from which to judge feasibility.

To the above-listed major constraints it is necessary to add three groups of factors:

Economic factors

Fish farming was originally initiated, designed and planned without concern for profitability because in the minds of the initiators, it was essentially a family subsistence activity. It has now been established that this approach does not produce sufficient incentive for fish farmers to pursue a new activity which requires at least a minimum of effort for the development of infrastructure, for maintenance and for financing the purchase of fry and feed.

Sociological factors

In some cases of donor-funded projects, the recipient countries and/or their nationals do not appear to have been given the opportunity to participate in discussions during the early preparation of the project documents. Some of the beneficiaries have no idea what the project is all about, let alone that it is for their own benefit. This is, of course most unfortunate but quite understandable. In a situation where most members of the target beneficiaries have a low level of education, there is bound to be a lack of effective communication between the beneficiaries and the project management. When the project implementation time is short, there is real danger that the project management team finds it difficult to resist the temptation to act on what they think is good for the beneficiaries without consulting them. This is not a simple matter and there is no simple answer to it. Nevertheless, the beneficiaries must be told all the relevant information and their views listened to carefully. This is because it is themselves who must work for the success of the project, especially after the donor's aid has come to an end. And, they can only do that effectively if they know what needs to be done and are in agreement with it, because they know or see that it is for their own benefit. Individual members of the group will only begin to be motivated when they can identify that what they are being asked to do leads to immediate benefit to them personally.

Political factors

Most fishery development projects have focused on technical and economic constraints, neglecting policy constraints. Very few governments include capture fisheries or aquaculture in their national development plans. This makes things difficult with regards to the development of fish farming projects because there would be no provision made in the development plan for research in aquaculture, extension service, infrastructure, credit, education of the farmers, etc.

The mission evaluated all the UNDP/FAO and other donor-funded aquaculture programmes in Kenya. A summary of their findings and recommendations is given below.

The mission found that the effectiveness of externally assisted aquaculture projects had not on the whole been impressive - clear exceptions had been the UNDP/FAO assisted projects to train extension workers (FAO/TCP) and to provide support to the subsequent extension service within the LBDA in Western Kenya. The main reason for these successes had been that the training and mobilization of extension workers to directly assist small-scale rural fish farmers had necessitated face-to-face contact with the intended immediate and long-term beneficiaries identified in government plans and policy. Immediate effects had resulted.

Other projects had been less successful for the following common reasons:-

The mission was of the opinion that strengthening of the host institutions in terms of organization, structure and managerial capacity was a pre-requisite of successful development; in addition to this, external assistance should be concentrated in the training of nationals at all levels, in both technical and managerial matters, and in the support of extension services.

The team did not find a single project whose objectives were to develop the managerial capacity of local staff; where training was indicated in the project document, it was limited to technology transfer through interaction between experts and nationals. Even when national staff were sent to institutions, the ‘right’ schools were not chosen, for example the choice of ARAC, Nigeria, for counterparts on the coastal aquaculture project was not particularly suitable for shrimp farming.

The only project (UNDP/FAO/BSF KEN/80/006) that had incorporated upgrading of the quality of staff in a meaningful manner was making significant progress, but its impact on a long term basis would depend on GOK's attitude to post-project activities.

For economic reasons, GOK had not been able to promptly meet its commitments in certain projects.

This mission evaluated Phase I of the fish farming project in the Lake Basin area and noted that all the original project activities could not be met within the original time frame. In view of this, and the achievements made by the project, the mission recommended that a four-year second phase of the project (1988–91) be launched with the following objectives:-

This mission evaluated Phase II of the LBDA Fish Farming Project, expected to end on 31 December 1991. It recommended inter alia that:

The project be extended by one year beyond termination date as had already been recommended by the Tripartite Review in March 1991.

During the second half of the extension period, a formulation mission be sent to Kenya to prepare a project document for a third phase to start in January 1993.

During the extension period, senior and junior project staff and farmers be extensively trained.

To guarantee sustainability, the third phase should include a clear budget for complete takeover of the project activities by the implementing agency (LBDA) when the third phase comes to an end.

Aquaculture has been advocated by the GOK as a promising development activity in the rural areas of Western Kenya. Although capture fisheries from Lake Victoria will continue to provide the major contribution of food supplies, aquaculture is expected to fill the gap between supply and demand.

Because Lake Victoria lies in this region, there is some concern that over-concentration on the fisheries of Nile perch might lead to minimize the potential role of aquaculture to increase the farmers' income and alleviate protein deficiency and other nutritional problems in rural communities of the region. However, Nile perch is mainly for export and more than 80 per cent is exported annually as fillets. In spite of the high production level of Nile perch and its industry, people in villages more than 30 km away from the lake shore, are generally not supplied with fresh fish other than that produced from aquaculture.

The latest available statistics up to 1990 as figures from field stations arrive a bit late, and compilation of national statistics takes some time. The best available data are those recently published by FAO (1993) from figures supplied by DoF over the last seven years' period (1985–1991) (Table 4).

Recent statistics (1988–91) in the Lake Basin area are given in paragraph 1.7.4(e), Table 5.

Table 4

Aquaculture production statistics (in metric tonnes)

| Fish species | 1985 | 1986 | 1987 | 1988 | 1989 | 1990 | 1991 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyprinus carpio | 4 | 7 | 5 | 82 | 187 | 293 | 271 |

| Oreochromis (Tilapia) niloticus | 113 | 114 | 121 | 169 | 416 | 405 | 451 |

| Oncorhynchus mykiss (ex Salmo gairdneri) | 93 | 98 | 80 | 215 | 118 | 111 | 96 |

| Salmo trutta | (n/a) | (n/a) | (n/a) | 92 | 201 | 200 | 191 |

| Penaeus spp. | 3 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 50 | 227 | 169 |

| Total | 213 | 224 | 210 | 561 | 972 | 1 236 | 1 178 |

Over the last 10 years, some of the most important UNDP/FAO-assisted fish culture development projects in Kenya were the following:

Pilot fish farm development at Amolem, West Pokot, as part of a UNDP/FAO/GOK arid-zone irrigation/settlement assistance project.

Development of coastal aquaculture - Phases I and II (shrimp), a UNDP/FAO/GOK project.

Training of aquaculture extension workers for LBDA (pre-project activity financed by FAO/TCP).

Development of small-scale fish farming in the Lake Victoria Basin (LBDA), a project funded by UNDP/BSF and GOK, and implemented by FAO (Phase I and II).

| Project No: | KEN/78/015 (FAO) | |

| Year started: | January 1979 | |

| Duration: | 2 years | |

| Funding: | Large agriculture project with a very small aquaculture component. | |

| UNDP: | USD 100 000 (estimate) | |

| GOK: | USD 50 000 (estimate) | |

Rationale

This irrigation project was designed to develop the food production potential of the arid and semi-arid regions of Kenya with a view to decreasing food dependency of these regions on other parts of the country; to provide opportunity for destitute nomads to lead more stable and prosperous lives; to establish self-supporting communities and to offset the destructive effects of encroaching desertification. No rationale was given for the aquaculture component.

Project objectives

There were no stated aquaculture objectives.

Output

Trials on culture of tilapias using feeds and organic manure.

Effects

There were no measurable effects.

Comments

The aquaculture component of the project was poorly conceived, no baseline study of the socio-anthropological and socio-economic predisposition of the community to aquaculture was undertaken, DoF was not involved, files do not indicate that any aquaculture consultancy visits were undertaken; a young UN volunteer was left to work on his own. Most of the Pokot people who live near the project area have a taboo against eating fish and tend to scorn those who do. The project could not be made economically viable because of the high cost of pumping water.

| Project No: | KEN/77/014 and KEN/80/018 (FAO) | ||

| Year started: | 1978 | ||

| Duration: | KEN/77/014: May '78 – July '82 (4 years) | ||

| KEN/80/018: July '82 – October '85 (3 years) | |||

| Funding: | Phase I | UNDP | USD 467 000 |

| GOK | USD 160 000 | ||

| Phase II | UNDP | USD 770 000 | |

| GOK | USD 150 000 | ||

Rationale

The tidal swampy lands along the coast of Kenya had been identified as potential areas for coastal aquaculture and therefore, in line with GOK National Development objectives of alleviating poverty, developing food sufficiency and promoting productive employment, it was recommended that the technical and economic viability of such farming be demonstrated through a pilot facility.

Project objectives

To examine the potential technical and economic viability of brackish/salt water aquaculture using locally available finfish and crustacean species,

To survey the availability of juvenile mullets, siganids and penaeids along the Kenyan coast.

To test polyculture techniques for the farming of these species on extensive, and later semi-intensive management regimes, using a purpose built tidal farm.

To train DoF staff in coastal aquaculture practices.

To disseminate project results to potential investors.

Project results

For various reasons, the first four years (Phase I) of the project proved too short a period to successfully achieve project objectives. The project was extended for 3 years (Phase II) maintaining the original objectives.

Output

The project has demonstrated that it is technically possible to culture Penaeus indicus and P. monodon under Kenyan conditions but reliable technical and economic data have not been produced.

| Project No: | TCP/KEN/2303 (FAO) | |

| Year started: | 1983 | |

| Duration: | 1 year | |

| Funding: | FAO | USD 198 000 |

| GOK | USD 100 000 | |

Project objectives

To organize and operate one training course (15-week duration) for 42 LBDA staff (7 district co-ordinators and 35 agents) on small scale fish farming and rural extension.

Project results

54 school certificate holders (all males) were trained for 5 months.

Effects and impact

Trained agents now constitute the grass roots workers for project KEN/80/006 (see below). The effects and impacts are by inference in this subsequent project.

| Project No: | KEN/80/006 (FAO) | |

| Year started: | March 1984 | |

| Duration: | 3 years (Phase I) | |

| Funding: | UNDP | USD 307 523 |

| GOK | USD 485 631 | |

| BSF | USD 500 000 | |

Objectives (Phase I)

The main aim was to develop rural small-scale fish farming in the Lake Victoria basin, in order to increase fish production in the region, providing animal protein for human consumption and additional income to small-scale fish farmers.

Project Results (Phase I)

By the end of Phase I of the project in 1986, the following objectives had been achieved:

Training

Construction and Rehabilitation of Ponds

Fish Farming Production

Fish farm production increased from 0.3 t/ha/year to 1 t/ha/year.

Database

A computerized Fish Farming Database for the LBDA region established

Fry Production Centres

An estimated 186 000 fingerlings from FPC distributed to farmers

Rationale for Phase II

The Project Evaluation Mission (for Phase I) in December 1985 noted that although the project had made some progress and created impact, the original objectives of the project, although still valid, had been defined too optimistically and could not be achieved in the original time frame. The Mission therefore recommended that a second phase (1988–93) be undertaken so that these objectives might be fulfilled.

Objectives (Phase II)

To extend credit facilities to progressive fish farmers through a revolving fund, with special attention to women groups.

Project results (Phase II)

Since the beginning of Phase II of the project, the following objectives have been achieved:

The GOK represented by LBDA and the beneficiaries at the grass-root level (individual farmers and women groups) consider the project a very important development activity for food supply, employment and increase in income. Recent statistics on aquaculture development in the Lake Basin region are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5

Aquaculture development in the Lake Basin

| Statistics | 1988 | 1989 | 1990 | 1991 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fish ponds | ||||

| • Total number | 5 934 | 5 992 | 7 190 | 7 445 |

| • Total area (m2) | 790 912 | 869 193 | 1 224 040 | 1 350 548 |

| • Average area (m2) | 144.5 | 160.0 | 179.0 | 190.0 |

| Fish stocks | ||||

| • Total weight stocked, in kg | 36 551 | 49 432 | 65 824 | 43 684 |

| • Total weight harvested, in kg | 158 102 | 210 214 | 298 894 | 195 378 |

| Average fish yield, in kg/100 m2/year | 19.99 | 24.18 | 24.42 | 14.47 |

Source: Lake Basin Development Authority statistics for the Districts of Bungoma, Busia, Kakamega, Kisii, Kisumu, Nyamira, Siaya and South Nyanza