Dear readers, This issue is dedicated to education and communication initiatives related to NWFPs/NTFPs. In our special feature, Citlalli López Binnqüist and colleagues share their experiences from the Universidad Veracruzana in Mexico, where two NTFP courses were introduced into forestry curricula. Also featured are two interviews: INBAR Director General Hans Friederich fills us in on training, research and knowledge management initiatives on bamboo and rattan; Cesar Sabogal from FAO provides us with an overview of a new tool: the Sustainable Forest Management (SFM) Toolbox, recently launched at the 22nd session of FAO’s Committee on Forestry. In our regional dispatches, Kristina Rodina, TRAFFIC, introduces us to an interactive toolbox on wild plants; Jenne de Beer returns to us with news from the Philippines, where innovative attempts to revive wild food traditions are unfolding. Finally, a recent GIZ-funded project in Mongolia is supporting NTFP-use through the development of training modules for forest workers and user groups in rural areas and the "Piacecibosano" network in Italy is working to facilitate communication between all actors in the food production chain. Readers are reminded to send contributions (including recent papers, projects, workshops, articles, etc.) to: [email protected]. Please do not hesitate to send feedback on our new NWFP Update well! SPECIAL FEATURE Teaching NTFPs to graduate students: a strategic pedagogic approach

Citlalli López Binnqüist, Maite Lascurain Rangel & Patricia Negreros Castillo |  © Citalli LopezUndergraduate and graduate forestry teaching programs are in decline worldwide (1). One possible explanation is decreased interest due to the perception that forestry is not as profitable as other technological careers, and the study programs and curricula are not keeping up with the changing realities and complex dynamics involved in the management of forest ecosystems around the world (2). © Citalli LopezUndergraduate and graduate forestry teaching programs are in decline worldwide (1). One possible explanation is decreased interest due to the perception that forestry is not as profitable as other technological careers, and the study programs and curricula are not keeping up with the changing realities and complex dynamics involved in the management of forest ecosystems around the world (2).

Furthermore, within the natural resources and forestry curricula, NTFP educational courses are almost nonexistent (3), leading to many missed opportunities. NTFP modules or programs could improve the analysis and management of timber and non-timber forest resources and could become an innovative pedagogic approach in rural and urban educational settings. | Read more We designed and implemented two NTFP teaching courses as optional inter-semester courses in the Universidad Veracruzana (UV), State of Veracruz, Mexico: “Introduction to Non Timber Forest Products” for graduate students from all UV faculties and “Integral Forest Management: wood and non-wood resources”, for graduate students of the Universidad Veracruzana Intercultural, a special program at UV with campuses in four indigenous regions of Veracruz.

Below we discuss some advantages of NTFP education gained from this teaching experience.

1) Bringing interdisciplinary experience and dialogue to the classroom.

NTFP courses require the understanding of both social and ecological processes and are inherently interdisciplinary, invoking the application of knowledge taught in a variety of other graduate programs. The use of tangible examples (e.g. some of the commonly eaten edible NTFPs), makes palpable the interrelation of social-cultural, economic, political, biological and ecological factors, and the need for understanding many different variables. For many students this becomes the first learning experience where they can observe and integrate different disciplinary methods and can realize the applied potential of their own fields of study.

Interdisciplinary communication starts with the design of the courses. Both NTFP courses were prepared and implemented by teams of scholars who are specialized in different disciplines, and who have work experience related to forestry (community forestry, agroforestry, silviculture). Teaching in the classroom is carried out as a joint effort; students can move beyond theory and observe in practice the personal and interpersonal challenges involved in any interdisciplinary work. This experience is not just academic but builds necessary personal qualities such as tolerance, respect and collaboration. The knowledge and attitude gained is valuable in the search for sustainable NTFP practices and is also useful for the future experiences of students in other work settings.

2) Building on intercultural experiences to strengthen local forest management initiatives.

Intercultural education has become widely mainstream in formal tertiary education in Latin America and around the world, with recent notable examples from Africa (4). Intercultural education seeks to understand and enhance the accumulation of ideas, practices and values of different societal groups. The construction of a dialogue that incorporates different views, knowledge systems and practices constitutes its base. In the context of biocultural diversity it has strong social justice implications and could steer the path for endogenous development (5, 6).

Within the Universidad Veracruzana Intercultural, where the majority of students have an ethnic/ indigenous origin, the incorporation of an NTFP course has proved an especially enriching learning experience. Frequently students themselves, and/or their families and/or communities participate directly in local and regional NTFP chains. These contextualized NTFP cases constitute an immediate reference that increases student interest in learning and exchanging experiences and knowledge related to the management, practices and evaluation of forest lands and resources. Since NTFPs are part of many of the students´ household production diversification and the integral management of forest resources, NTFP courses can be a study framework closer to the students’ views, practices and principles than the majority of the forestry teaching programs with their separation of wood and non-wood resource practices. In most forestry planning local knowledge has been systematically marginalized. Teaching NTFPs in biocultural contexts represents a path for establishing inclusive and productive forms of knowledge and for strengthening endogenous initiatives directed to the maintenance and defense of land and forest resources.

Citlalli López Binnqüist is an anthropologist with experience on NTFPs and community forestry management, full time teacher and researcher working in the Centro de Investigaciones Tropicales, Universidad Veracruzana (UV) and collaborator with People and Plants International (PPI). Maite Lascurain Rangel is a biologist with experience in traditional agroforestry systems for the production of edible fruits and plants, and full time researcher in the Instituto de Ecologia A.C., and Patricia Negreros Castillo, who researches the ways that tropical silviculture works in rural and indigenous communities for the adaptation of best forest management practices, is a full time teacher and researcher working in the Instituto de Investigaciones Forestales UV and collaborator with PPI.

For more information, please contact: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]

References:

(1) Van Lierop, P. 2003. Trends in forestry education. Presented at the XII World Forestry Congress, Quebec City, Canada, 21-28 September 2003.

(2) Innes, J.L. 2010. Professional Education in Forestry Chapter 5. In Ward, D. (ed.) Incorporating text from the first edition of Commonwealth Forests on Technical Education in Forestry. Commonwealth Forests.

(3) Guariguata, M.R. and Evans, K. 2010. Advancing tropical forestry curricula through Non-Timber Forest Products. International Forestry Review 12(4):418-426.

(4) Pedota, L. 2011. Indigenous intercultural universities in Latin America: interpreting interculturalism in Mexico and Bolivia. Master Thesis. Loyola University. Chicago, Illinois, USA.

(5) Haverkort, B. and Rist, S. (eds.) 2007. Introduction. Endogenous Development and Bio-Cultural Diversity. The interplay of worldviews, globalisation and locality. COMPAS Series on Worldviews and Sciences 6. COMPAS / Centre for Development and Environment CDE.

(6) Santos, Boaventura de S. 2006. Chapter 1. La Sociología de las Ausencias y la Sociología de las Emergencias: para una ecología de saberes. In Renovar la teoría crítica y reinventar la emancipación social. Consejo Latinoamericano de Ciencias Sociales CLACSO. Buenos Aires, Argentina. INTERVIEWS  INBAR Director General Hans Friederich on bamboo and rattan INBAR Director General Hans Friederich on bamboo and rattan

“For some reason, NTFPs, including bamboo and rattan, have not been fully “accepted”. We need to try and address the lack of understanding and awareness among different sectors, as well as the problematic legal frameworks that hinder NTFP development in many countries…The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are an opportunity to do this.”

Read more 1. In your presentation at COFO 22 in June, you described Bamboo as a “miracle species” of the 21st century and also spoke of its valuable contribution to the forthcoming Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Do you have the same views about Rattan and NTFPs? What are the key messages you would deliver to governments currently drafting the SDGs (and in turn, donors and the wider public) with regards to the contribution of bamboo [and rattan/NTFPs ] – to the post-2015 development agenda?

We have defined bamboo as a miracle plant because of the many opportunities it offers. Bamboo is a grass, and you can harvest it regularly without damaging the surrounding ecosystem norsuffering negative aspects such as deforestation which can come from cutting standing timber. It is also an amazing resource for soil restoration, erosion control and landscape restoration. Bamboo really only needs irrigation in its first year, doesn’t require agro-chemicals and can grow without fertiliser, so in this respect it is very effective. Whilst growing, it absorbs high volumes of CO2 which can help reach REDD+ targets. Once cut, it is an alternative to timber, and is often described as being stronger than steel. It is useful in textiles, paper pulp and as a fuel source – both locally and on an industrial scale.

Rattan is very different. The selective “cut and re-grow” method doesn’t usually work for rattan, but because it generally comes from natural tropical and subtropical forests – contrary to bamboo that, these days, often comes from plantations or agro-forestry systems – it is arguably even more integral to Sustainable Forest Management (SFM), because you are automatically forced to look at SFM.

In the context of the post-2015 development agenda, the SDGs have been the “red thread” in developing INBAR’s 15-year strategy (2015-2030). Both bamboo and rattan can contribute to reaching some of the SDGs currently on the table. The goal on Poverty Reduction, for example, given that the management, harvest and trade of bamboo and rattan, and many other NWFPs, often involves poor people. Access to Energy is another key area. This applies especially to bamboo as a source of energy at household and community levels, but potentially on an industrial scale, for example, as a source of bioethanol or biodiesel. INBAR is exploring the development of bamboo as an alternative to timber charcoal in Tanzania, Ghana and Ethiopia, where we have established projects. Bamboo also has the potential to contribute to Urban development and green construction, as do many other NTFPs like jute fiber [genus Corchorus] for example. The potential of both bamboo and rattan in Sustainable Consumption and Production and Climate Change have also not been fully recognized. Bamboo and rattan can be grown by poor people and help them adapt to climate change by providing a sustainable source of livelihoods. In current REDD+/Climate talks, however, the benefits of bamboo are not even mentioned. We need to raise awareness and understanding of its potential to contribute to climate change adaptation in particular. Finally, bamboo, rattan and other NTFPs can contribute to broader environmental goals, with some having a direct role. But for some reason they have not been fully “accepted”. We need to try to address the lack of understanding and awareness among different sectors, as well as the problematic legal frameworks that hinder NTFP development in many countries. The SDGs are an opportunity to do this.”

2. INBAR was set to be the driving force behind the Global NTFP Partnership launched in Marrakech in 2006, and very much still is. Admittedly, progress has been slow at a global level. What is your “vision” for this partnership, particularly with regard to educating and communicating with decision makers and the wider public about the importance of NTFPs for food, nutrition, livelihoods and the relatively benign affects of harvest from an environmental standpoint if compared to timber?

The Global NTFP Partnership is an independent entity which INBAR is helping to support and manage. We would like to see this become a more effective partnership by linking up with some of the global research institutions that also work with NTFPs such as FAO and CGIAR. The idea is to broaden the support base and connect all of these global institutions so it truly develops.

3. Bamboo processing at an industrial scale is particularly successful in China, but take up has been slow in Latin America and Asia. How can INBAR address this gap, for example, by mobilizing a country-knowledge exchange initiative to further develop bamboo processing at a global scale? What other efforts do you envision?

China is the world’s pioneer in bamboo development, which incidentally is one of the advantages of INBAR being headquartered here, and this has been achieved primarily with one very particular species called “Moso” on which its bamboo industry is based. Over the past 30 years China has developed huge new areas of Moso plantations that give easy access to and supply of abundant, high quality quantities of raw bamboo. It had developed policies that support Research & Development in bamboo, especially for innovation, and for private sector investment, and it has an abundance of very cheap labour, though costs are now increasing - growing and processing bamboo is labour intensive. This level of development hasn’t really happened in other nations, but is a model that could be adapted elsewhere. Sharing these experiences and the learning gained with its other members, and promoting discussion, is one of INBAR’s priorities.

As an example, during recent discussions with our partners in Latin America, I was surprised to learn that although there are also abundant bamboo resources in Brazil, there is practically no bamboo industry in the country. It seems that the benefits of bamboo and of how to best develop it are just not well known there yet. Brazil is not even a member of INBAR. The first step is trying to broaden membership to include Brazil and other countries in the region, with the help of global institutions, so we can discuss these issues with governments. The next step is to engage the private sector and get them on board. But governments need to set up supporting policy frameworks - the legal frameworks in many countries for bamboo and rattan are not as supportive as they could be. In many countries there are strict laws on cutting forest resources. Unless NTFPs are recognized and their use supported by governments, it will be very difficult to engage the private sector and develop processing in the region. INBAR has a very important role to play here, and in the next decade will need to work with its members to address the lack of understanding and awareness in different regions and promote knowledge exchange between different countries.

INBAR is really the one-stop-shop for information on bamboo and rattan. One of our tasks in the years ahead is to try to make this information more accessible, in partnership with other institutions. What annual events should we be at, for example? How can we use our own channels to disseminate information? We have recently hired a communication expert to help us address these issues.

4. Rattan is facing a similar fate to many of its NWFP counterparts when they were replaced with synthetic substitutes or “crops” (e.g. vegetable ivory, rubber, etc.). What efforts is INBAR undertaking to revive the sector (if at all) and to raise awareness about its place in many local livelihoods (for example through a roundtable discussion with donors?).

As I said before, rattan is very different from bamboo, and in some ways more challenging. It is mostly grown in natural forests, and in many places it is under threat. For this reason some countries, like Indonesia, have prohibited the export of raw rattan. However, this has had the unintended consequence of damaging the domestic industry, as local production capacities are unable to cope with the glut in supply. Indonesia is currently reviewing its strategy. With Indonesia and other ASEAN countries, INBAR is developing an ASEAN-wide sustainable management programme to help revive the rattan sector and bring back knowledge and methods on sustainably managing and using the resources.

5. One of the key areas INBAR hopes to address in the next few years is knowledge management. You are doing some particularly interesting work in Africa in this regard in the context of landscape restoration. Can you tell us more about this work?

We have landscape restoration and land management programmes in Ethiopia and Ghana, and possibly one brewing in Burundi. In Ethiopia, the Government has recognized bamboo as a key tool in landscape restoration. We are hoping to upscale these pilot projects in the future and use the experience from Asia in Africa and beyond, a kind of knowledge exchange within [Africa] and across continents. A Bamboo Training and Research Center is currently in the pipeline for Africa. With funding from China, the center will be established in Ethiopia, with INBAR providing technical and managerial support.

6. There seems to have been a proliferation of international standards and import regulations in recent years (FSC, Lacey Act, EUTR, Australia Illegal Logging Prohibition Bill, etc.), which has delivered many benefits, but at the same time can often confuse consumers. What efforts is INBAR taking to make sure consumers are confident about the ecological, legal and social credentials of bamboo and rattan in this climate?

You are absolutely right. INBAR is seeking clarity on this issue. While it supports Sustainable Forest Management (SFM) broadly, it really does not support any particular initiative. It is working with China to coordinate an International Standards Organization (ISO) working group. The INBAR Council also has a working group in which members jointly come up with thoughts and recommendations on international standards and regulations, because there really is no one-size-fits-all solution. There are many interesting initiatives taking place. The Rainforest Alliance is indirectly exploring NTFP certification (“alternative fibres”), FSC is also doing some work in the area. INBAR is certainly open to the idea; INBAR members have discussed the idea of launching a bamboo certification scheme.

We are ready to engage with the European Forest Institute (EFI), particularly in light of the forthcoming review of the EUTR. INBAR is trying to exempt NTFPs from EUTR regulations as they really cannot be tagged on to timber regulations. In the US and elsewhere, support for NTFPs has been more challenging, but this is where INBAR can play a role by increasing awareness and understanding, and being present in important discussions, such as the forthcoming IUFRO meeting in Salt Lake City where there will be a working group on NTFPs. On a global level, we are preparing stories on our achievements with bamboo and rattan to help share our experiences in the public domain.

Dr. Hans Friederich is the Director General of the International Network for Bamboo and Rattan (INBAR). INBAR is an intergovernmental organization dedicated to improving the livelihoods of the poor producers and users of bamboo and rattan, within the context of a sustainable natural environment.

For more information, please contact: [email protected]. For further information about INBAR’s NTFP Global Programme, please contact: Dr. Manoj Nadkarni, NTFP Programme Manager, [email protected]. Read more: www.inbar.int/2014/04/inbar-prepares-to-launch-flagship-rattan-programme/

NWFPs at COFO 2014: Interview with Cesar Sabogal, FAO The Sustainable Forest Management (SFM) Toolbox was launched at FAO’s Committee on Forestry(COFO) in June 2014. It is a collection of tools, case studies and other resources, organized in modules and created to provide forest owners, managers and other stakeholders with easy access to those resources for the implementation of SFM. The SFM Toolbox contains one Module on the Management of Non-Wood Forest Products, and others relevant to the sector. 1. Who is the NWFP Module aimed at?

This module is aimed at all actors – such as local communities, the private sector, governments, traders and consumers – involved in the management, use and marketing of NWFPs.

2. Who developed the SFM toolbox and corresponding modules, including the module on NWFPs?

A team within the Forestry Department was formed in 2012 to start developing the SFM Toolbox, and early this year also collaborated with other Departments within FAO. The modules were prepared by FO staff, in some cases involving professionals from outside FAO as well as consultants. The NWFPs module in particular was initiated by Christopher Muenke.

3. What are the perceived benefits/learning outcomes of exploring the module?

A module is a section of the toolbox covering a thematic area relevant to the implementation of SFM. It provides an overview of the thematic area (e.g. Management of NWFP) and offers relevant toolbox resources (tools and cases) for learning and support.

The SFM toolbox is tailored to both, users who have very basic knowledge and wish to enlarge it, as well as expert users who wish to discover the latest developments in terms of useful tools and cases. As such, in the module of NWFP, users will find a very basic overview of NWFP, as well as the latest useful tools (e.g. publications, videos, software...) and cases that can help in improving NWFP management.

Users can also give their views on existing tools and cases, and participate in the forum to share their challenges or doubts with other forest managers. Finally, all users can suggest improvements to the modules, and new tools and cases to be added. The collaboration of all will continuously develop and enrich the SFM toolbox.

4. The NWFP module is one of many. There are others that are also relevant to NWFP management, governance and harvest. How can an individual interested in NWFPs get the most from the SFM toolbox?

One major aim of the SFM Toolbox is to help users plan and put in practice a more comprehensive approach and actions to implement SFM on the ground. In line with this, each module provides a list of related modules the user can further search in. In the case of the NWFP module, the list includes the following modules: Markets and development of forest-based enterprises; Participatory approaches and tools in forestry; Forest inventory; and Silviculture in natural forests.

5. NWFP management is complex for many reasons, not least because it inherently includes such a variety of products from different ecological and geographical environments, which often require very different approaches. How does the NWFP module take the multi-faceted dimension of the sector into account?

The module’s title is Management of NWFPs and it provides basic and more detailed information on the process of NWFP management, including planning, harvesting, marketing and trade, as well as links to tools for NWFP management and case studies of effective management. We realize that harvesting and processing of NWFP encompass a wide range of knowledge and capacities that were not sufficiently covered in the present module and therefore the preparation of a complementary module on NWFP harvesting may be necessary. On the other hand, the tools and cases included in the module of NWFP management will cover more specific information by product and/or context.

6. To what extent are efforts being made to make the modules more “accessible” to local communities (e.g. translation, delivery methods, and so on)?

Modules are part of the toolbox and so far it’s only available through the internet. We are planning to regularly produce and update a CD-ROM that could be used for the kind of situations you mention. If the interest is only in the modules per se, they can also been printed in PDF from the system.

7. Is the toolbox an evolving effort? If so, what are the "next steps" in the context of NWFPs?

The toolbox is a work in progress that will be evolving over time. One main feature of the toolbox is that it’s interactive, allowing users to provide suggestions for new tools and cases as well as to the texts of the modules themselves. In the case of the NWFP module, as mentioned above (question 5), we are considering the preparation a complementary module on NWFP harvesting. We encourage the active participation of the readers of “NWFP Update” to continue enhancing the sections related to NWFPs in the SFM toolbox.

Cesar Sabogal is a Forestry Officer at FAO. For more information, please contact: [email protected]

More from COFO 22: www.fao.org/forestry/57758/en/ REGIONAL DISPATCHES Hungary: Wild plants star in innovative online toolbox Kristina Rodina An online interactive “Traditional and wild” toolbox, has been created by TRAFFIC, the wildlife trade monitoring network, to showcase the use of a variety of wild plant species for traditional medicine and food in Hungary, the Czech Republic, Slovenia, Poland and beyond (1). The state-of-the-art toolbox was created as part of an EU-funded “Traditional and wild” project, aimed at preserving knowledge about sustainable harvesting of wild plant resources and promoting its traditional collection and use to reduce social and economic disparities in Central Europe. Read more: The toolbox is an online suite of tools and learning resources specifically designed for the general public, scientific and educational institutions, and other stakeholders working with or interested in wild plant resources. The Toolbox aims to raise public awareness about the importance and values of wild medicinal plants as well as to foster sustainable use of knowledge and expertise of traditional wild plant collection among populations of Central Europe and other regions.

The toolbox guides visitors on a journey through the wonderful world of wild plants, challenging them to test their knowledge about the plants themselves and traditional harvesting practices. The information contained can be used in a variety of contexts, for training purposes and in workshops to enrich knowledge about wild plants. It comprises eight sections including comprehensive information about 30 commonly used wild-collected plants in Central Europe and beyond, such as Leopard’s Bane Arnica montana, Common Nettle Urtica dioica, Cape Aloe Aloe ferox, Ginseng Panax Ginseng and others.

Such information is traditionally passed on by word of mouth from generation to generation, but today it is being lost through a combination of fewer wild plant harvesters operating and an increasingly urbanized population.

To provide quantitative up-to-date knowledge about wild plant resources, the toolbox offers an extensive infographics section, which includes information about important plant areas (IPA), threats to plants, IUCN Red list, CITES, top exporters/importers of wild plants, sales leaders in the global and European herbal medicinal markets, organic wild collection products and areas, and many other interesting facts.

An overview of worldwide projects incorporating use of the FairWild Standard including those on FairWild-certified Frankincense (Commiphora and Boswellia species) from Kenya and Liquorice root Glycyrrhiza uralensis from Kazakhstan, is also included in the toolbox. The FairWild Standard was originally developed by organizations including TRAFFIC to support efforts to ensure plants are managed, harvested and traded in a way that maintains populations in the wild and benefits rural producers. An associated online cartoon has also been launched as the part of the toolbox to explain and promote the use of the FairWildStandard.

Also included within the online toolbox is a Resource section, intended for users of wild harvested plants, companies seeking information about sustainable harvesting and trade, government bodies charged with regulating such trade and those looking for a better understanding of the sector. The section contains five parts, namely:

- information on wild plants,

- policies, regulations and strategies,

- training materials and guidance,

- voluntary standards and certification schemes, and

- organizations and databases.

The toolbox is available in English, with some sections in Polish, Hungarian, Slovenian, Czech and Roma. In May 2014, the toolbox won “Site of the Day” for its innovative creative design and ease of use from the prestigious theFWA.com and cssdesignawards.com websites.

(1) Original source: www.traffic.org/home/2014/5/27/wild-plants-the-stars-of-innovative-online-toolbox.html.

Kristina Rodina is a Medicinal Plants Officer for TRAFFIC, Europe. For more information, please contact : [email protected]

Philippines: Wild Food Revival Philippines: Wild Food Revival

Jenne de Beer The Negritos of the Philippines, with their ancient hunter gatherer background, share a strong relationship with the natural environment in which they live. For these indigenous peoples, among which the Batak of Palawan and the Ata of Negros island, wild gathered forest foods are a traditionally a healthy element of the diet. Today, these foods are still much appreciated in the communities, but traditions are under severe pressure. More recently, a Negrito Cultural Revival and Empowerment Initiative has emerged, in which communicating the richness of traditional forest foods plays a prominent role. In this framework, two major events took place at the end of 2013. Read more: 1) A first ever Batak Cultural Revival Festival cum Development Forum, held in Roxas, Palawan, 14 – 15 last October . The festival turned into a wonderful celebration of the identity and culture of the Batak with songs, music, dance and games. The highlight was a traditional (largely wild gathered) food contest between the six Batak settlements of the island.

The event was organized by the “Nagkakaisang Tribu ng Palawan” (NATRIPAL) with Batak leaders, Municipality of Roxas, Non-Timber Forest Products Task Force, the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples (NCIP).

2) A “Wild Food Night”, staged at The Museum Cafe in Bacolod City, Negros Occidental in November 2013 revolved around cooking demonstrations and tastings of exquisite Ata “beyond organic” foods. Ingredients, wild gathered from Ata territory in the mountains up north, included such items as: aquatic snails, palm heart, ferns, Collybia albuminosa “termite” mushrooms and, for desert, a large flow of Apis dorsata honey.

Furthermore, before the actual cook and taste sessions, a photo exhibit reflecting previous Negrito food-themed festivals elsewhere in the Philippines, opened at the same location.

The well attended event – another first - was part of Indigenous People's day at the annual Negros Organic Farmers' Festival.

Jenne de Beer is considered the “father” of the NWFP movement by his Asian collaborators, drawing global attention to this important source of subsistence resources for local livelihoods as well as income for the rural and upland poor. He is currently a facilitator of the “Negrito Cultural Revival & Empowerment Initiative” in the Philippines. An important focus of this initiative is the revival of wild food traditions. He is also the former executive director of the NTFP Exchange Programme for South & Southeast Asia and a recipient of the ISE/Darrell Posey Field Fellowship Award for ethno-ecology 2010/2011. For more information, please contact:[email protected]

Mongolia: NTFP training module for forest workers and user groups in rural areas Bjoern Schueler & Sissy Sepp On behalf of the program “Biodiversity and the adaptation of key forest ecosystems to climate change” [1], of German bilateral cooperation, GIZ, a team of ECO Consult, Germany, was called to develop a training module on NTFPs in Mongolia. The training formed a part of a vocational education scheme for forest workers; the ultimate target audience included organized user groups and the general public in rural areas. [1]The main objective of the umbrella program (2012-2015) is to maintain so-called “key ecosystems” by way of sustainable management while also improving the living conditions of rural populations. The program reaches out to rural populations threatened by climate change and poverty, organizations, municipalities, households and organized groups of users managing forests and using/marketing products derived from the forest. In December 2013, ECO Consult consultants first conducted an on-site survey to collect data about the utilization of NTFPs and the state of traditional knowledge, and explore linkages to access and benefit sharing. Recommendations were developed on the basis of the findings.

The survey revealed a significant gap between potentials of NTFP valorization and actual practice in the project area. Despite their tentative traditional knowledge (kind of products to collect, location, application) the rural society displayed a very limited background in “scientific” information. This leads to a relatively spotty, sparse utilization of the resource and not a complete realization of income potential. For an efficient structural improvement of this situation curricula, amendments and trainings were negotiated with the communities. Forest workers were envisaged to act as multipliers, to broaden knowledge about NTFPs i.e. disseminate to the rural population their benefits, best practices of harvesting and processing methods. It was also recommended that the curricula for Mongolian forest workers at vocational school level be revised.

Existing curricula did not provide topographically concise and handy information, so the team developed a tailor-made workbook, which could also cope with the requirements of different target groups and individuals within those groups. Different channels to present the materials were chosen to meet different needs, including a manual, a factsheet displaying distinctive product features and a powerpoint presentation for each prevailing NTFP. While the size and composition of the factsheets enables field use, the powerpoint presentations are meant for in-class use by professors, combined with a continually amendable collection of instructional videos for the target groups. Included in the workbook are marketing hints, a mapping of related value chains complemented by a continually amendable collection of instructional videos for target groups. Users’ extension in economic skills was found to merit further attention.

A training module for each NTFP category which is important in the Mongolian context was elaborated. For example, the survey found that dead wood, berries and herbs were the most important NTFPs. Interviews with Mongolian NTFP experts suggested that mushrooms and nuts (Pinus sibirica) were also in the list of major marketable NTFPs. The workbook thus included a chapter on dead wood, for example, and how to produce charcoal. Charcoal production could be a good opportunity for future income increasing by processing dead wood. Teachers at vocational schools can adapt the material to products that are important in their respective environments.

The workbook was inspired by the “NTFP Curriculum Workbook” by Kathryn Lynch (2005). For more information, please contact:

GIZ program contact Ulaanbaatar:

Klaus Schmidt Corsitto ([email protected])

Responsible for the project at GIZ Ulaanbaatar:

Munkhuu Sergelen ([email protected])

Chuluuntsetseg Dagvadorj ([email protected])

ECO Consult:

Sissy Sepp ([email protected])

Bjoern Schueler ([email protected])

Further resources:

GIZ Program Biodiversity and the adaptation of key forest ecosystems to climate change: http://www.giz.de/en/worldwide/17729.html

ECO Consult Sepp & Busacker Partnerschaft: www.eco-consult.com/

Lynch, K. 2005. Non-timber Forest Product Curriculum Workbook.

Hartwig, J. 2014. Die Vermarktung der Taiga. Franz Steiner Verlag.

Castleman, Michael. 2001. The New Healing Herbs: The Classic Guide to Nature's Best Medicines

Janakiraman, V. 2014. Analysis on current status of Pinus Sibirica nuts trade, by identifying and mapping its value chain, in order to produce findings and recommendations for future value chain development interventions. GIZ

Italy: “Piacecibosano”, a food production network based on public participation as an outstanding example of sustainable land development Miriam Bisagni & Ettore Capri  Piacecibosano is a network that aims to facilitate communication between all actors in the food production chain, from producers, scientists, and policy makers to consumers in search for more environmentally-, socially- and ethically-sound products.” Piacecibosano is a network that aims to facilitate communication between all actors in the food production chain, from producers, scientists, and policy makers to consumers in search for more environmentally-, socially- and ethically-sound products.”

Piacecibosano, founded by the strategic vision of the Province of Piacenza and coordinated in partnership with the Research Centre for Sustainable Development OPERA- Università Cattolica Sacro Cuore of Piacenza, is a synergetic initiative aimed at developing a sustainable and healthy food production network based on public participation. It is a network that promotes increased awareness among all actors in the food and agriculture production chain towards sustainable territorial production and consumption. In addition, it: contributes to the creation of an active network of actors (organizations, research centers, enterprises and consumers) who value a territory’s products and nourishes relations that lead to increased consumer trust in the production chain; develops synergies to communicate the health benefits, quality and sustainability of food and agricultural products; implements concrete models that favor sustainable territorial development through initiatives that inform, educate/train, communicate and perform action-research.

Today, the Piacecibosano network is made up of 35 public and private actors representing the sustainable food and agriculture production chain in a given territory. A chain that begins with scientific research and develops through the entire food chain from the production stage to the transformation, distribution, commercialization, organized purchasing, retail and consumption stages. Health, development, but above all sustainability are the key words of this work. Regardless of the reasons behind choosing a sustainable approach, every step taken in this direction is beneficial for both enterprise and society as a whole. Sustainability thus becomes a factor in competitiveness and development if it is generated by an interconnection between communication, participation, but also a connection with a territory and its culture; these are the basic elements upon which innovation, understood as the continuous renewal of knowledge and existing technologies, is constructed.

Piacecibosano focuses primarily on communication and education in the context of food and agriculture. This is done by organizing events such as the “CAFFEEXPO” (www.caffeexpo.it) informal conversations on sustainability, which facilitate, for example, the communication of EXPO themes to consumers and citizens of different territories to increase awareness on sustainable production and consumption. The network also focuses on food education by initiating innovative participatory experiences that are shared and planned together with secondary schools and shed a light on the quality of school lunches in primary schools by valuing the identity of food and its production process.

Beekeepers and associations of beekeepers are just one example of the actors participating in the Piacecibosano network and communicating the nutritional, social and environmental benefits of sustainable honey production. Blueberries, blackberries and mushrooms from the mountainous Apennine region – including val Nure, val Trebbia and Val Tidone – are just some examples of sustainable “Piacecibosano” products supported by the network.

The coordinators of the network are Dr. Miriam Bisagni, sociologist and president of the Piacecibosano Association, and Professor Ettore Capri, Environmental and Plant Chemistry Professor at Università Cattolica Sacro Cuore of Piacenza, (UCSC) and Director of the OPERA Research Centre (www.operaresearch.eu).

For more information, please contact: [email protected] and [email protected]

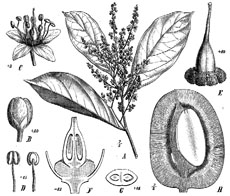

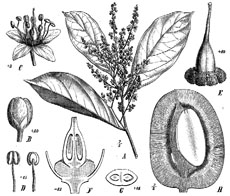

PRODUCT WATCH  African Bush mango trees (Irvingiaceae) African Bush mango trees (Irvingiaceae)

A study published in Plant Ecology and Evolution looks at bitter and sweet African bush mango trees which produce NWFPs in humid lowland areas of West and Central Africa. The study links differences in socio-cultural groups to the agroforestry status of bush mango trees in order to identify the key factors influencing their abundance and conservation. The bitter tree varieties are found in the wild in the Volta forest region in Togo, for example, but slash and burn agriculture and overexploitation of fruits have put pressure on the resource. Meanwhile traditional fishing systems (using bush mango twigs), a traditional selection strategy and intensive land commercialization severely threaten sweet bush mango tree genetic resources, explain the authors. For more information, please see: www.ingentaconnect.com/content/botbel/plecevo/2014/00000147/00000001/art00010 GENERAL NEWS FROM AROUND THE WORLD: Mixing science and traditional knowledge in forestry Spanning over 650 million hectares globally and boasting plentiful resources, community-run forests provide important income for 400 million indigenous people who generate up to US$100 billion annually, according to a recent report by the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED). They provide a variety of opportunities and products, from fruits to herbal medicines... Read more: www.scidev.net/global/forestry/feature/mixing-science-and-traditional-knowledge-in-forestry.html

Putting people at the centre of forest policies Countries should put more policy emphasis on maintaining and enhancing the vital contributions of forests to livelihoods, food, health and energy, FAO said today.

FAO's flagship publication The State of the World's Forests (SOFO), presented at the opening of the 22nd Session of the FAO Committee on Forestry (COFO), shows that a significant proportion of the world population relies on forest products to meet basic needs for energy, shelter and some aspects of primary healthcare - often to a very high degree. Read more: www.fao.org/news/story/en/item/236722/icode/

Forests as important as farming for some rural communities A global study carried out by the Poverty and Environment Network (PEN) has helped shed light on the role forests play in enhancing people’s livelihoods, confirming that forests do provide an important source of rural income, but challenging some of the long-held assumptions about how these resources are used. Read more: http://news.mongabay.com/2014/0714-dparker-forest-livelihoods.html

Bushmeat: FAO warns of fruit bat risk in West African Ebola epidemic Increased efforts are needed to improve awareness among rural communities in West Africa about the risks of contracting the Ebola virus from eating certain wildlife species including fruit bats, FAO warned today. FAO is working closely with the WHO to raise awareness of the transmission risks from wildlife among rural communities that hunt for bushmeat - or meat obtained from the forests - to supplement their diets and income. Read more: www.fao.org/news/story/en/item/239123/icode/

Bamboo sprouts up in the concrete jungle Buildings have been made out of bamboo for thousands of years and now a team of University of British Columbia researchers is making the construction material even better. They have developed a higher quality, lighter and more moisture-resistant bamboo panel that could replace the demand for wood, steel and concrete building materials. Read more: http://news.ubc.ca/2014/07/29/bamboo-sprouts-up-in-the-concrete-jungle/

Insects for food and feed: First international conference The first international conference on insects for food and feed brought over 450 participants from 45 countries together to discuss about the state of the art in research, business and policy making in this new developing sector. The conference was a milestone in the recognition of the professional insect industry. Various stakeholders gathered for the first time, with a clear message: insects for feed and food are viable solution for the protein deficit problem. Read more: www.fao.org/forestry/edibleinsects/86385/en/; www.nature.com/news/time-to-eat-insects-1.15192?WT.ec_id=NEWS-20140513

Registration for Training Session on Modelling NWFPs is now open Registration for the Training Session on Modelling NWFPs under the COST Action FP1203: European NWFPs Network is now open. This course will be held in El Escorial (Madrid, Spain) between 29 September and 3 October 2014. Trainees are invited to submit their applications by 14 August 2014. For application details, please see: www.nwfps.eu/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/Training-school-Call-2014-07-20_definite.pdf or contact: Dr. Rafael Calama: [email protected].

RECENT LITERATURE

Read more Acunzo, M. & Vertiz, V. 2014. Promoting communication in agriculture and rural development. FAO’s priorities and initiatives in 2014. Glocal Times: The Communication for Development Journal. (available at: http://ojs.ub.gu.se/ojs/index.php/gt/article/view/2874).

Allendorf, T.D., Brandt, J.S., and Yang, J.M. 2014. Local perceptions of Tibetan village sacred forests in northwest Yunnan. Biol. Conserv. 169:303-310.

Fellow, P. (ed). 2014. Insects as Food. Food Chain Journal, 4:2. (available at: http://practicalaction.metapress.com/content/l903x8202076/?p=86fcdef9607140e296c8f9a24b8ca8a8&pi=0).

Jusu, A. and Sanchez, A.C. 2014. Medicinal plant trade in Sierra Leone: threats and opportunities for conservation. Econ. Bot. 68(1):16-29.

Khaine, I., Young Woo, S., & Kang, H. 2014. A study of the role of forest and forest-dependent community in Myanmar. Forest Science and Technology. (available at: www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/21580103.2014.913537#tabModule).

Larinde, S.L., Oladele, A.T., Nwakaego, O. 2014. Non Wood Forest Products in poverty alleviation and its implication in species conservation in Emohua Local Government area, Rivers state, Nigeria. Journal of Environmental Extension. (available at: www.ajol.info/index.php/jext/article/view/99331).

Lund, H.G. 2014. What is a forest? Definitions do make a difference - An example from Turkey. Avrasya Terim Dergisi 2(1):1-8.

Miah, M. D. , Shalina, M. 2014. Scaling up REDD+ strategies in Bangladesh: a forest dependence study in the Chittagong Hill Tracts. Forest Science and Technology, 10(3): 148-156.

Nielsen, M.R., Jacobsen, J.B. & Thorsen, B.J. 2014. Factors determining the choice of hunting and trading bushmeat in the Kilombero Valley, Tanzania. Conserv. Biol. 28(2):382-391.

Rodina, K., Timoshyna, A., Smolej, A., Krpan D., Zupanc E., Németh E., Ruzickova G., Gáspár, G., Szántai J., Draganik M., Radácsi P., Novák S., & Szegedi S. 2014. Revitalizing traditions of sustainable wild plant harvesting in Central Europe.TRAFFIC and WWF Hungary. (available at: www.trafficj.org/publication/14_Traditional_and_Wild.pdf).

Stevens, C., Winterbottom, R., Reytar, K. & Springer, J. 2014.Securing Rights, Combating Climate Change.USA: World Resources Institute, Rights and Resources Initiative. (available at: www.wri.org/sites/default/files/securingrights_report_0.pdf).

Van Huis, A., van Gurp, H. & Dicke, M. 2014. The Insect Cookbook: Food for a Sustainable Planet. USA: Columbia University Press. (http://cup.columbia.edu/book/978-0-231-16684-3/the-insect-cookbook).

Vihotogbé, R., Kakaï, R.G., Bongers, F., van Andel, T., van den Berg, R.G., Sinsin, B. & Sosef, M.S.M. 2014. Impacts of the diversity of traditional uses and potential economic value on food tree species conservation status: case study of African bush mango trees (Irvingiaceae) in the Dahomey Gap (West Africa). Plant Ecol. Evol. 147(1):109-125.

Wiersema J. H., Leon B. 2013. World economic plants: A standard reference. USA, CRC Press, 792 pp.

Yen. A.L. (forthcoming). Journal of Insects as food and feed. (available at: www.wageningenacademic.com/jiff). |

INBAR Director General Hans Friederich on bamboo and rattan

INBAR Director General Hans Friederich on bamboo and rattan Philippines: Wild Food Revival

Philippines: Wild Food Revival