WHAT TO DO IF THINGS GO WRONG

What to do if things go wrong?

Contract farming involves production by farmers under agreement with buyers for their outputs. This written agreement covers in detail the arrangements for both parties, giving the transparency and clarity on what is going to happen along the way. Hence, when drafting a contract, it is important that both buyer and farmers attempt to foresee any problem that may arise and affect successful implementation of the agreement. It is a good practice to identify the risks and to include possible solutions in the contract.

In spite of all efforts, sometimes things go wrong and there is a contract breach, meaning the failure by one or both parties to perform one or more of their obligations under the contract without an acceptable excuse.

There are three possible scenarios:

1) Neither party is at fault;

2) It is the farmer who cannot keep his/her side of the agreement;

3) It is the buyer who cannot keep his/her side of the agreement.

SCENARIO 1: Neither party is at fault

Unforeseen events can happen independently of the intentions of the parties but with negative impacts on the contract agreement. Natural phenomena, for example, constitute some of the most common external factors that can affect farmers’ performance. Floods, droughts, unpredictable climatic changes, plagues attacking crops, or livestock diseases, are all natural events that can make it impossible for farmers to respect their product, process and delivery-related obligations discussed above.

Legal systems often define events like these as force majeure. This category also includes other kinds of events outside the control of the parties, such as government decisions to change policies related to agriculture such as export bans, armed conflicts and strikes that may affect either the production process or the availability of transport for delivery. As laws sometimes provide only general principles, buyers and farmers need to agree on specific force majeure circumstances to be included in the contract.

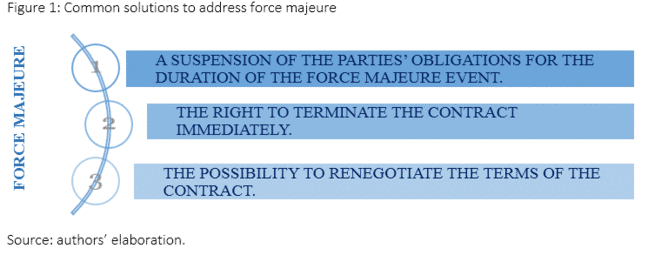

In the case where force majeure events occur, contract farming agreements commonly allow for a suspension of the parties’ obligations for the duration of the force majeure event. However, suspensions cannot be indefinite: the contract must indicate a time-limit and say what will happen after this period. These options usually include termination of the contract or renegotiation of the terms of the contract (Figure 1).

Force majeure clauses may excuse the farmer from the obligation to deliver the product but they do not usually entitle the farmer to receive any payment, or excuse them from repaying any loans received. However, some contractors may recognize that when dealing with small uninsured farmers, they may need to accept the inclusion of some risk-sharing clauses. These may include accepting partial repayment from farmers for outstanding loans for inputs provided, or deferring repayment until the next harvest season. Some contracts may also require farmers to purchase agricultural insurance from an approved provider. In these instances, the buyer may help farmers to purchase this insurance at a reduced price.

SCENARIO 2: Farmers cannot keep their side of agreement

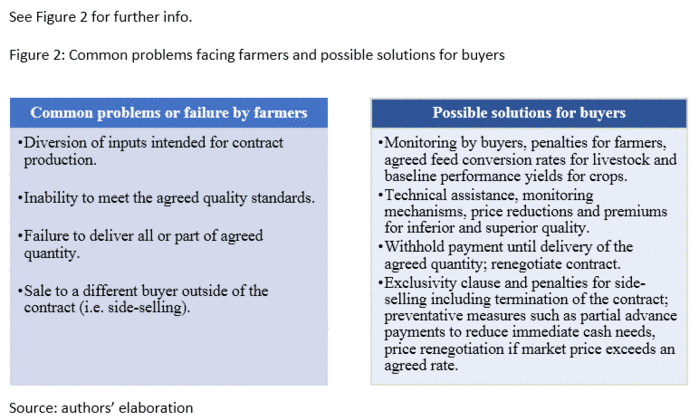

Apart from force majeure events, farmers can fail to perform properly or to comply with their contractual obligations for other reasons such as: failure in land preparation, diversion of inputs for uses other than those intended under the contract, non-compliance with the agreed quality standards, failure to deliver all or part of the agreed quantity and, of course, the commonly mentioned downside of contract farming for buyers, known as side-selling.

Side-selling occurs when farmers sell the product to a different buyer who may have offered a higher price compared to the one agreed in the contract, or to a buyer who may offer instant cash payment. Farmers may engage in side-selling for opportunistic reasons or because they need instant cash to support household needs. Side-selling can cause the termination of the contract, ruin a farmer’s reputation, and prevent them from engaging in other safe and long commercial relationships with trusted buyers.

SCENARIO 3: Buyers cannot keep their side of the agreement

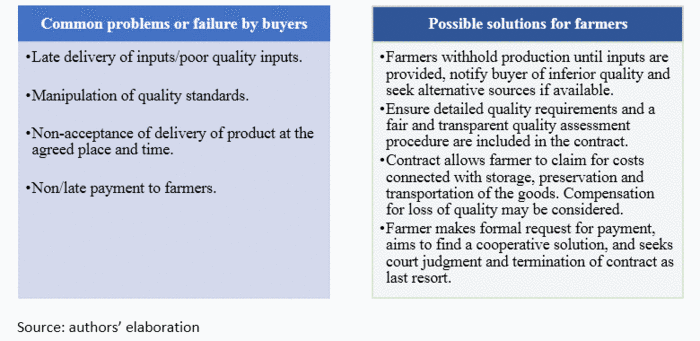

Buyers can also fail to deliver on their commitments under the contract, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Common problems facing buyers and possible solutions for farmers.

All these problems can lead to conflicts between farmers and buyers. It is in the interests of both to find cooperative solutions and maintain the relationship. Instead of terminating the contract due to low quality products, buyers can decide to pay a lower price for it. Also, in the case of late of delivery of inputs, farmers may be able to find another input provider and purchase substitute inputs, with the contractor being liable for any price difference.

Options to resolve conflicts

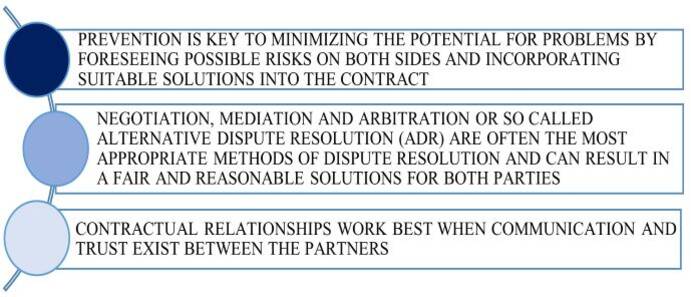

Prevention is an important part of minimizing the potential for problems by aiming to foresee possible risks and incorporating solutions into the contract, if disagreements do occur and parties are not able to find a shared solution, then a stepwise process described below should be followed:

Step 1. Communication: Negotiation is the most basic means of settling differences. It is back-and-forth communication between the parties of the conflict with the goal of trying to find a solution. Farmers may request the help of a trusted facilitator (e.g. government extension agent, NGO or representative from local/national farmer associations), to help them to set up a discussion with the buyer.

Negotiation should be voluntary, private and confidential, quick and inexpensive as well as informal and unstructured. Moreover, both parties should control the process, make their own decisions and reach their own agreements (no third party decision maker). This negotiation process should lead to enforceable agreements that constitute a win-win solution.

If this does not work, see step 2.

Step 2. Mediation: Use an independent third party to bring parties together and try to help find a solution. The mediator assists the parties in settling their dispute, but does not have the authority to impose a solution. This is the preferable approach in resolving differences and contracts should be specific on how mediation is to be done.

The mediation process is characterized for:

- Promoting communication and cooperation

- Providing a basis for you to resolve disputes on your own

- Being voluntary, informal and flexible

- Remaining private and confidential, avoiding public disclosure of personal or business problems

- Reducing hostility and preserving ongoing relationships

- Allowing to avoid the uncertainty, time, cost and stress of going to trial

- Allowing to make mutually acceptable agreements tailored to meet your needs.

In sum, it can result in a win-win solution.

Step 3. Arbitration: If mediation does not work, and where this is possible, refer to arbitration institutions. Arbitration refers dispute to a neutral third party whose decision will be binding and enforceable under the law. In the case of quality disputes, the contracted parties could refer to this agency for an independent assessment. Arbitration is typically an out-of-court method for resolving a dispute. The arbitrator controls the process, will listen to both sides and make a decision. Like a trial, only one side will prevail. Unlike a trial, appeal rights are limited.

Arbitration is often private (unless the limited court appeal is made) and can be used voluntarily. It tends to be less formal and structured than going to court, depending on applicable arbitration rules, plus it is usually quicker and less expensive than going to court. Each party will have the opportunity to present evidence and make arguments, and may have a right to choose an arbitrator with specialized expertise.

Afterwards, a decision will be made by the arbitrator which may resolve the dispute and be final. The arbitrator’s award can be enforced in a court. However, if nonbinding, parties still have the right to a trial.

Negotiation, mediation and arbitration or so called alternative dispute resolution (ADR) are often the most appropriate methods of dispute resolution and can result in a fair and reasonable answer/solutions for both parties. ADR allows partied to reach resolution earlier and with less expense.

Step 4. Legal action: As an alternative, or if arbitration is not available, parties can refer to law courts. However, this should be avoided if possible as it is time-consuming, costly and not normally suitable for resolving contract farming disputes.

Litigation is involuntary −the defendant is not given other choice than participate−, formal and follows structured rules of evidence and procedure. Each party has the opportunity to present its evidence and argument and cross-examine the other side according to procedural safeguards. It is public and therefore court proceedings and records are open. The decision is based on the law and can be final and binding. Right of appeal exists and the losing party may have to pay all the litigation costs.

Good practices to take into account when drafting a contract: preparing for a bad outcome

Contracts work well when communication and trust exist between the partners – if this can be built, then the relationship is likely to succeed in the longer term. However, things can take an ugly turn, so the contract should also foresee what to do under those circumstances.

- Contracts should include clauses concerning force majeure events. It is desirable to specify in detail all events that could qualify, and to clearly state what will be the responsibilities of the parties in the case of force majeure events.

- Contracts should include clauses relating to actions (remedies) that may be applied when one party fails to perform for any reason other than force majeure and the performance is not excused. Emphasis should be on arriving at mutually acceptable, cooperative solutions.

- Contracts should propose a sequential approach to dispute resolution. First, the parties should attempt to resolve difficulties on their own. If this does not work, mediation should be tried. Failure of mediation could then lead to arbitration or, alternatively, to the national courts.

Click here for the presentation on "What to do if things go wrong?"

Click here for the case study on "Contract Breakdown and Conflict Resolution: The Case of Vanilla in Tonga"