Food loss reduction through partnerships evidence based interventions

The United Nations Joint Project (UNJP) is carrying out food loss assessments using the FAO methodology and provides technical support in the deveopment of a PH policy and strategy framework.

United Nations Joint Project (UNJP) on food losses in the Island of Timor-Leste

Activities of the Global Initiative on Food Loss and Waste Reduction (SAVE FOOD Initiative) are now a global initiative. Testimony to this is the implementation of the United Nations Joint Project (UNJP) on food losses in the Island of Timor-Leste located in Southeast Asia. Implementation of the projected in Timor-Leste started on 28 July 2015 and the FAO Food Losses Technical Officer, Cephas Taruvinga went there to train researchers and kick-start the project. The training was held at the University of Timor-Leste (UNTL) and twenty-one participants composed of food loss researchers, enumerators and extension staff attended the training.

The UNJP, a Government of Ireland funded project on food loss reduction is one of the many projects under the Save Food Initiative. The project objective is to identify food loss causes and develop solutions to address the causes through research, awareness raising and collaborating with private and public partners around the world. The project is being implemented by FAO and IFAD under a collaborative arrangement where FAO provides post-harvest technical support to IFAD-funded projects, and the Government of Ireland provides the financial resources. The countries where the project is being implemented and the crops covered are; Ethiopia – maize and teff, Malawi – maize and groundnuts, and Timor-Leste – maize and rice. Already in each country a research agency has been identified to undertake the studies based on the FAO case study methodology.

From 28 July to 1 August 2015, the FAO Technical Officer was in Timor-Leste to train researchers from the University of Timor-Leste (UNTL); the institution selected to carry out the studies. The training program focused on two key areas that are fundamental to carrying out food loss studies. The areas are; an understanding of the post-harvest supply chain and the FAO food loss study methodology. An understanding of the post-harvest supply chain helps researchers in planning their activities based on the supply chain structure. It also makes it is easier for them to identify the critical loss points, their causes and the likely solutions to address the causes. An understanding of the FAO methodology enables them to use a method whose results are comparable to other countries implementing the project.

Post-harvest supply chain

The PH supply chain can be defined as an agricultural system after harvest with a sequence of activities and operations designed to handle and deliver commodities to end markets. Food losses occur along a post-harvest supply chain, and there are various causes of losses at different stages of a supply chain. The food pipeline developed by Bourne in 1977 provides a good depiction of the Post-harvest supply chain.

(Source: Bourne, 1977, mimeo)

Bourne’s diagram shows where food losses are likely to occur and the agents that cause damage to the grain. However, the diagram does not tell us the actual causes of the losses but it shows us the agents that cause the damage. The actual cause of losses are factors like rain during harvesting, lack of sufficient labour, use of traditional methods of grain handling or storage and lack of skills. Other causes of loss could be poor farmer organization, lack of finance or market access, lack of phytosanitary protocol, inadequate testing facilities, misaligned government policies, use of defective vehicles, etc.

Making a distinction between agents that inflict damage on the grain, and the factors that influence or encourage those agents is important because this ensures that the correct solution to address a loss problem is applied. The agents causing the damage like rodents and insects are not the actual cause of losses – but these could be considered as symptoms of causes of losses. Making this distinction between symptoms and the actual loss causes is very important, and it was highlighted during the training.

Symptoms and causes

In many research studies what we have noted is that what researchers identify as causes of losses from a management perspective, are in reality symptoms of the causes. For example, molds and pests have been identified as causes of losses yet they are not what you would manage to limit their effect or to reduce the losses. The actual causes are the factors that are encouraging molds and rodents to thrive, and this could be poor storage or harvesting before the crop has dried. In reality, the occurrence of molds and rodents is a signs or symptom of something more fundamental that is lacking or not being management properly. The missing element or poor management is what a study in food losses using the FAO methodology should identify not the symptoms of the causes. If there is an occurrence of rodent damage, the most likely cause of food loss is the lack of rodent barrier, poor hygiene or poor storage.

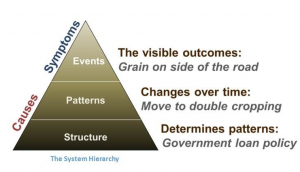

According to the ADM Institute for the Prevention of Post-harvest Loss “what we observe as the problem (an event) may be a symptom of more systematic factors”. To explain the distinction between symptoms and food loss causes, the ADM website uses the Systems Hierarchy pyramid.

Source: ADM Institute for the prevention of post-harvest losses

The upper end of the pyramid represents the symptoms and below that are the pattern of events and the structure of the whole system. If the structure malfunctions, the whole system collapses. Therefore, it is important that food loss researchers are aware of the symptom and cause distinctions specific to the supply chain being studied.

Categorization of causes

Another aspect that emphasized during supply chain training was the categorization of food loss causes. As we noted, actual causes of losses are normally factors relating to the structure of the post-harvest system. This makes the relationship between causes and losses complex because causes are not always directly related to the losses or loss point. The cause of loss is always located away from the loss point, with other events occurring in between before the actual loss occurs. As an example let’s take grain that spoils in storage due to high moisture. After investigations, it turns out that the grain was received with high moisture at an aggregation point and then transferred to a storage facility where it started to go bad.

On analyzing the grading process at the aggregation point, it turned out that the aggregation point was using a faulty grading protocol resulting in grain being taken in at 15% moisture, yet the safe moisture content for storage is 13%. In this case, the cause of grain spoilage at the storage facility is not the high moisture content, but the use of a wrong grading protocol at the aggregation point. In trying to locate the loss point relative to the cause, it will be noted that the loss occurred at a storage facility some km away from the aggregation point, and the grading protocol was developed by the National Bureau of Standards which falls under the Ministry of Trade and the grading protocol is implemented by the plant inspectorate division which is under the Ministry of Agriculture.

To identify these complex causes and analyse them, it is best to categorise the causes as micro, meso or macro (HLPE, 2014). The causes can also be categorised as direct or indirect causes.

Micro level causes These are causes of losses, at each particular stage of the post-harvest supply chain where losses occur along the supply chain that result from actions or non-actions of individual actors at a stage, in response or non-response to external factors. Micro causes are found along the supply chain. Meso-level causes These are secondary causes or structural causes of losses. Meso level causes can be found at the same or at another stage of the post-harvest supply chain than where losses happen. They result from how different actors are organized, their relationships along the supply chain, the state of infrastructures, etc. Meso-level causes can contribute to the existence of micro-level causes, or determine their extent. Macro-level causes These are higher level causes of losses. These cover more systemic issues, such as a malfunctioning supply system, the lack of institutional or policy conditions to facilitate the coordination of actors. Macro level causes favor the emergence of meso and micro-level causes. In the end, they are a major reason for the wider extent of post-harvest losses |

Adapted from HLPE, 2014. Food losses and waste in the context of sustainable food systems.

Direct causes These are causes located near the loss point and affect the commodity directly. Like micro causes they are due to bad decisions by chain actors. Direct causes are usually effects of something else and can be considered as symptoms of a structural or underlying problem. Direct causes recur quickly if what makes them happen is not addressed. Examples are poor storage, inadequate labour, delayed transport, fumigation failure, and delayed harvesting. Indirect causes These are causes located away from the loss point, and they cause losses through other factors. Indirect causes do always have an immediate and may not be apparent. Examples of indirect causes are a lack of resources, lack of market access, price controls by government. Meso or macro causes are considered as indirect causes. |

From our example of grain spoiling at a storage facility, the failure to test correctly at the aggregation centre and the failure to manage the moisture at the storage facility are considered micro or direct causes. The use of an inappropriately developed grading protocol is considered a meso or indirect cause and the wrong design of the grading protocol is considered a macro cause. This categorization help to identify the source of the problem and develop appropriate solutions - thus it is important that food loss researchers are aware of this categorisation.

FAO food loss case study methodology.

The second training session focused on the FAO food loss study methodology. The FAO methodology was developed to standardized research studies on food losses. Past results of most studies even within the same country show loss estimates that vary widely. One of the main reasons for this variance is the use of different methods for estimating losses. Also most of the methods that have been used do not tell us the most important causes of food losses, nor the impact of the solutions and we do not know which solutions are cost-effective and feasible in terms of food security and impact on the environment.

The FAO methodology was designed to address these shortcomings, and it has four stages that include preliminary screening, surveying, load tracking and solution finding.

Preliminary Screening: This stage focuses on the use of secondary data obtained from documents, reports, and expert consultations by phone, emails or interviews. During the screening stage, the researchers also validate the selection of the subsectors and then identify the actual supply chain/s to be studied. It is also during the screening exercise that potential loss points or the low loss points are identified, questionnaires are developed, and the field activities are planned.

Surveying: This is the stage when the questionnaires are administered. The questionnaires are differentiated by chain actors like producers, processors, warehouse operators, distributors, wholesalers and retailers. This survey stage is complemented by ample and accurate observation of activities along the supply chain.

Load Tracking: This is the stage when quantitative, and qualitative analyses are carried out either at specific stages or along the supply chain depending on the areas that have been identified as critical loss points.

Because of the complexity of the load tracking process and also since it is the stage when physical evidence of losses is collected, and solutions are suggested by actors, more time during training was spent on this section.

There are three load tracking approaches that researchers can adopt. However, each approach has its advantages or disadvantages. The three load tracking approaches are as follows;

- Tracking a specific load in sequence.

- Tracking any one of the sample loads or units in sequence.

- Tracking any one of the sample loads in any order convenient to the researcher.

- Tracking a specific load in sequence involves following the same load along the supply chain as shown below.

Tracking a specific load

Tracking a specific load in sequence is suitable for short cycle commodities like perishables unlike grains because durable products might remain at one location longer than the study period; for example, when the grain is in storage for a long period . Tracking a specific load has the disadvantage that the load can terminate or be delayed while the researcher is still available to carry out observations. The reason for termination or delay could be because the load reached the end of its life cycle, or the actor is engaged in another activity like attending a funeral. Also, the identity of the load being tracked can change or disappear as commodities are moved, mixed or transformed. Also continually observing one or the same actors for an extended period creates actor fatigue or the researchers end up taking part in the activities resulting in distorted results.

The second load tracking approach involves tracking any one of the sample loads or units in sequence. The researcher moves to the next stage and studies any of the sample units available but in sequence along the supply chain.

Tracking any one of the sample loads/units in sequence

The advantage of this approach is that if a sample load that is being tracked becomes unavailable, a representative substitute is tracked in replacement of the missing or inactive previous one. Also, if a load that is being tracked disappears, its identity is preserved in another representative unit. Thus unlike the first tracking option, this second option has the advantage of having more units or loads to study or observe.

The disadvantages of option two are that the researcher might still fail to observe supply chain activities in sequence due to logistical difficulties as in option one. However, since the second option allows the researcher to substitute loads with representative loads, this is a better option than the first option one.

The third option involves tracking any one of the sample units in the order that is logistically convenient to the researcher and ticked off. In this option, the observations are made randomly based on the nature of study or activity the researcher want to observe and the results later analysed based on the supply chain framework.

Tracking any one of the representative loads in any order.

The other advantage of this approach is that there are more chances to find a sample load to observe and also, the load-tracking process can be completed in a very shorter time, and it saves on resources.

The disadvantages are that because the post-harvest sequence is not followed, this might create confusion on the ground between the researchers and the actors. However, this can be addressed through constant communication with actors on the ground. The other disadvantage is that it requires a highly skilled post-harvest researcher who can carry out random observations in any direction and be able to fill missing gaps, make an analysis and draw the right conclusions. This is why the UNJP project emphasizes the need to engage skilled postharvest specialist because even under normal circumstances it is difficult to track the load from the beginning to end without breaking the sequence.

Solution Finding: This is the final stage of the methodology where solutions to address the identified causes of losses are developed. For each potential solution, an intervention has to be proposed to implement it, and the technical and financial feasibility of the interventions have to be determined. The cost of the intervention could be private (equipment, training, and packaging) or public (infrastructure, tax benefits, credit facilities or policy change). The economic feasibility should be based on at least ten years of operation of the proposed improvements.

The training carried out in Timor-Leste on; supply chain basics and FAO methodology, does not guarantee the success of a study if study implementation is based on the aspects covered in the training. These should complemented by engaging competent researchers who have an understanding of the local market and environment and should innovate during planning and undertaking field activities.

Cephas Taruvinga

Technical Officer Losses

FAO AGS