What is sustainable food value chain development?

This platform is based on FAO’s sustainable food value chain (SFVC) framework. The SFVC framework integrates two concepts that have become popular in development thinking and practice over the last decade: sustainability and value chains. These concepts are not always well understood and may be interpreted differently by different people. By being specific about the concepts and how they fit together, the SFVC framework aims to promote a better understanding of their fundamental nature, to facilitate more effective knowledge exchange and implementation. This section summarizes the main elements of the framework. More details can be found here.

Defining a sustainable food value chain

A food value chain (FVC) consists of all the stakeholders who participate in the coordinated production and value-adding activities that are needed to make food products.

A sustainable food value chain is a food value chain that:

• is profitable throughout all of its stages (economic sustainability);

• has broad-based benefits for society (social sustainability);

• has a positive or neutral impact on the natural environment (environmental sustainability)

The SFVC concept recognizes that value chains are dynamic, market-driven systems in which vertical coordination (governance) is the central dimension and for which value added and sustainability are explicit, multidimensional performance measures, assessed at the aggregate level.

The Concept of Value-Added

In the SFVC framework value-added refers to the difference between the non-labor cost of producing food and the consumer’s willingness to pay for it, adjusted for externalities.

more

more

When talking about value chains, the chain part of the concept is relatively straightforward: the producer is linked to the aggregator, who is linked to the processor, who is linked to the distributor, who sells to the final consumer. The value part of the definition is perhaps less well understood. In the SFVC framework, value added refers to the difference between the non-labour cost of producing food and consumers’ willingness to pay for the food, adjusted for externalities. This means that value added is best understood by looking at the ways in which it is captured by various stakeholders – as profits, wages, taxes, consumer surpluses and externalities (Figure 1). Externalities can be positive or negative. For example, a food processor may pollute a river, which affects the income of fishers, or build a road to its plant, which benefits the rural communities living alongside it.

Figure 1 – The Value-Added Concept in Food Value Chain Development

Source: FAO, 2014

A central notion demonstrated in Figure 1 is that SFVC development is not merely about linking smallholder farmers to a particular value chain. Four other types of value added are created, some of which may be even more important than linking smallholders to the FVC, such as job creation and consumer benefits. Most rural poor people, including most subsistence farmers, can likely be expected to escape poverty sustainably only through securing decent jobs – most people derive their livelihoods from jobs, not from running a business (and farming is a form of business). Similarly, if an FVC develops in ways that enable it to deliver healthier, cheaper food in greater abundance, there will be a large developmental impact, even without any additional smallholder farmers being included in the chain, as everybody consumes food.

The Concept of Sustainability

In SFVC development, a holistic triple bottom line approach is followed, in which there are three main dimensions to sustainability: economic, social, and environmental.

more

more

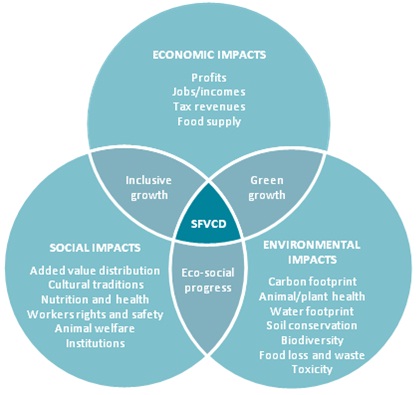

The SFVC framework is also explicit on the meaning of sustainability, to avoid giving rise to misunderstandings. In SFVC development, a holistic “triple bottom line” approach is applied, which recognizes three main dimensions of sustainability: economic, social and environmental (Figure 2). In the economic dimension, a value chain is considered sustainable if the activities carried out by each stakeholder are commercially viable, or fiscally viable for public services. In the social dimension, sustainability refers to socially and culturally acceptable outcomes in terms of the distribution of benefits and costs associated with the increased value creation. In the environmental dimension, sustainability is determined by the ability of value chain actors to generate positive of neutral impacts on the natural environment from their activities. By definition, sustainability is a dynamic concept in that it is cyclical and path-dependent: the sustainability of a value chain’s performance in one period strongly influences its performance in the next one.

Figure 2 – The Concept of Sustainability in Food Value Chain Development

Source: FAO, 2014

The central notion illustrated in Figure 2 is that SFVC development approaches sustainability holistically. For example, if the SFVC approach is used to address animal disease control, any proposed measure for upgrading the FVC to deal better with animal diseases will have to be assessed against all the other elements of sustainability to ensure that there are no undesirable impacts. Issues to be considered will include the upgrade’s impacts on farm-level profitability; and whether the upgrade will have different impacts on poor and rich farmers, possibly increasing the divide between them.

The sustainable food value chain development framework

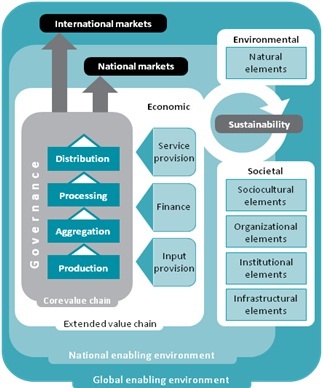

The SFVC development framework considers the FVC as the core of a system of complex economic, social and natural environments that determine the behaviour and performance of farms and other agrifood enterprises (Figure 3).

more

more

Figure 3 – The Sustainable Food Value Chain framework

Source: FAO, 2014

The core FVC comprises the value chain actors who produce or procure products from the upstream level, add value to these products and then sell them on to the next level. These actors carry out four functions: production (farming, fishing, forest harvesting or agroforestry), aggregation, processing, and distribution (wholesale and retail). The aggregation step is especially important to FVCs in developing countries, where efficiently aggregating and storing small volumes of produce collected from widely dispersed smallholder producers is often a major challenge.

FVC actors are linked to each other and to their wider operating environment through a governance structure. There are horizontal linkages among the actors at a particular stage of the chain, for example farmers organizing themselves into cooperatives; and vertical linkages within the overall chain, for example farmers providing their produce to food companies through contracts.

Ultimately, value is determined by consumers’ choice of food items to purchase on national and international markets. The implication is that SFVC development starts from an opportunity in the market place and works backwards through the chain to identify what aspects need to be improved to capture this opportunity.

FVC actors are supported by business support providers, which do not take ownership of the value chain’s product, but play an essential role in facilitating the value creation process. Together with chain actors, these providers represent the extended FVC. They supply physical inputs such as seeds and packaging materials, or financial or non-financial services such as loans, insurance, transport, laboratory testing, spraying, information, and marketing studies.

FVC actors and support providers operate in an enabling environment, the nature of which has major impacts on their performance. Various societal and environmental elements can be distinguished in this enabling environment. Societal elements include socio-cultural elements (religion, history, language, etc.), organizational elements (ministries, schools, research and development facilities, national commodity associations, etc.), institutional elements (policies, laws, customs and other socially embedded rules, private sector-based rules such as voluntary standards, etc.), and infrastructural elements (roads, markets, ICT, electricity grids, backbone public irrigation structures, etc.). Natural elements include freshwater sources, soils, biodiversity, climate, and so on.

The central notion derived from the analytical framework, aside from end markets being the main drivers, is that SFVC development positions FVCs in a broader system in which there are key leverage points where the impact of a change is maximized and where the root cause of a problem – and therefore the most effective solution – may be located at some distance from the observed problem. For example, to assist farmers in adopting a promising new technology, it may be far more effective to change service provision or a regulation, than to work directly with the farmers.

The sustainable food value chain development paradigm

VCs, as engines of growth, create added value that, as already indicated, has five components: salaries, profits, taxes, consumer surpluses and a net impact on the environment, positive or negative. This value added sets in motion three growth loops that relate to economic, social and environmental sustainability, and directly impacts poverty and hunger.

more

more

FAO’s core mission, engraved in marble at its Headquarters entrance, is to help bring about a world free from hunger. It is therefore important to understand how SFVC development is linked to food security.

The SFVC development paradigm starts from the premise that food insecurity is principally a symptom of poverty (Figure 4). Households that have sufficient financial resources at all times will create the effective demand that drives the supply of food. On the supply side, competitive improvements in the food system will reduce the costs of food products to consumers, or increase their benefits. As engines of growth, FVCs create value added that – as already indicated – has five components: salaries, profits, taxes, consumer surpluses and a net impact on the environment, positive or negative.

This value added sets in motion three growth loops that relate to economic, social and environmental sustainability and that have direct impacts on poverty and hunger (Figure 4): i) an investment loop, driven by reinvested profits and savings; ii) a multiplier loop, driven by the spending of workers’ increased incomes; and iii) an ecosocial progress loop, driven by public expenditure on the societal and natural environments. As well as commercial and fiscal viability, the sustainability element of SFVC development involves a shift to institutional mechanisms that lead to more equitable distribution of the increased value added and reduced use of and impact on non-renewable natural resources. The three sustainability dimensions are closely related: social and environmental sustainability are increasingly important issues in determining market access and competitiveness.

Figure 4 – The Sustainable Food Value Chain Development Paradigm

Source: FAO, 2014

Initially, SFVC development focuses mostly on improving efficiency to reduce food prices and increase food availability, thus allowing households to buy more food. However, as their incomes increase, households tend to spend more money on higher-value food (i.e. food with improved nutritional value, greater convenience, health benefits or better image) rather than increasing the amount of food they consume. In turn, this evolution of consumer demand becomes a core driver of innovation and value creation at each level of the FVC, leading to continuous improvement in the food supply and increasing benefits to consumers.

A central point emerging from this development paradigm is that SFVC development is less about moving from a static point A to an (improved) static point B, than it is about setting in motion or speeding up positive feedback loops that continue to drive improvements along the various dimensions of sustainability.

Principles of sustainable food value chain development

SFVC development takes a holistic approach that identifies the interlinked root causes of why value-chain actors do not take advantage of existing opportunities.

more

more

SFVC development calls for a particular approach to analysing the situation, developing support strategies and plans, and assessing developmental impact. This is captured by ten interrelated principles (Figure 5). The approach is not about simply developing long lists of often well-known constraints and then recommending ways of tackling them one by one. Rather, SFVC development takes a holistic approach that identifies the interlinked root causes that explain why value chain actors do not take advantage of existing opportunities.

Figure 5 – Principles of Sustainable Food Value Chain Development

Source: FAO, 2014

The ten principles are grouped into three phases of a continuous development cycle. In the first phase, measuring performance, the FVC is assessed in terms of the economic, social and environmental outcomes it delivers today relative to a vision of what it could deliver in the future (Principles 1, 2 and 3). SFVC development programmes should target the value chains with the greatest gaps between actual and potential performance.

In the second phase, understanding performance, the core drivers of performance (or the root causes of underperformance) are exposed by taking three key aspects into account: i) how value chain stakeholders and their activities are linked to each other and to the economic, social and natural environment (Principle 4); ii) what drives the behaviour of individual stakeholders in their business interactions (Principle 5); and iii) how value is determined in end markets (Principle 6).

The third phase, improving performance, follows a logical sequence of actions based on the analysis conducted in phase 2: developing a specific and realistic vision and an associated core FVC development strategy that stakeholders agree on (Principle 7); and selecting the upgrading activities and multilateral partnerships that support this strategy and that can realistically achieve the scale of impact envisioned (Principles 8, 9 and 10).

Conclusion

SFVC development provides a flexible framework for addressing many of the challenges facing food system development.

more

more

Misunderstanding of its fundamental nature can easily result in limited or unsustainable impact. Even when practitioners understand and rigorously apply the principles of SFVC development, the approach cannot solve all the problems in the food system. FVCs cannot provide incomes for everyone, cannot incorporate trade-offs at the food system level, and cannot always avoid all the negative impacts for all stakeholders and all elements in the environment. Public programmes and national development strategies are needed to address these limitations. However, such programmes and strategies are largely financed through tax revenues generated in FVCs, thus placing value chain development in general, and SFVC development in particular, at the heart of any strategy aimed at reducing poverty and hunger in the long run.