What is forest degradation?

Forest degradation is the reduction of the capacity of a forest to provide goods and socio-cultural and environmental services. It involves a change process that negatively affects the characteristics of a forest (e.g. growing stock and biomass, carbon stock, biodiversity, soils, and aesthetic values), resulting in a decline in the provision of goods and services. This change process is caused by disturbances (although not all disturbances cause degradation), which can vary in extent, severity, quality, origin and frequency. Disturbances may be natural (e.g. fire, storms, drought, pests and diseases), or human-induced (e.g. unsustainable logging, invasive non-native – “alien” – species, road construction, mining, shifting cultivation, hunting and grazing), or a combination of both natural and human-induced. Human-induced disturbance may be intentional, such as that caused by logging or grazing, or it may be unintentional, such as that caused by the spread of an invasive alien species. There are also indirect or underlying reasons for forest degradation, such as poverty, inappropriate policies, and unclear tenure rights.

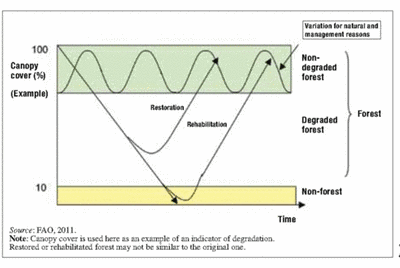

Forest systems always have an inherent range of natural variation and succession stages, and natural or human-induced disturbances do not necessarily lead to degradation. Degradation occurs when the production of an identified forest good or service is consistently below an expected value and is outside the range of variation that would be expected naturally.

Although it is complex to define and measure, forest degradation is a serious problem. It has adverse impacts on forest ecosystems and the goods and services that forests provide; for example, it is considered a significant source of land-related greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. It is estimated that, in 2010, 27 percent of forest landscapes worldwide (about 1.5 billion hectares) were degraded.

There is often confusion between the concepts of deforestation and forest degradation. Deforestation is the long-term loss of forest, with no guarantee that the forest will re-establish through natural regeneration or silvicultural measures; it results in a decrease in forest area. Forest degradation does not involve a reduction in forest area but, rather, a qualitative decrease in forest condition. Forest degradation often leads to full-scale deforestation, however, because degraded forests are more easily converted to agricultural lands. Figure 1 depicts the forest degradation continuum, and deforestation.

Why must forest degradation be addressed?

Why must forest degradation be addressed?

Forests provide a wide range of services. For example, they protect soils from erosion, regulate the water regime, capture and store carbon, produce oxygen, provide freshwater and habitat, help reduce fire risk (in the tropics), and produce wood and non-wood forest products. Forest degradation, therefore, adversely affects millions of people who depend, wholly or in part, on forest goods and services at a local scale, and billions of people who benefit from forest services at a regional or global scale. Specifically, for forest owners and managers, forest degradation is a direct threat to their livelihoods as it reduces a forest’s productivity and profitability, and it is a clear indication of unsustainable practices in the forests under their supervision.

It has been estimated that more than 2 billion hectares of deforested and degraded forest land worldwide is potentially suitable and available for restoration. Bringing degraded areas under sustainable management would reverse the trend of degradation, help forest landscapes to recover, and restore the associated forest goods and services. This would not only replenish the productive capacity and diversity of forest and land resources, it would yield economic, social and environmental benefits, including the mitigation of, and adaptation to, climate change.

Degradation is mentioned explicitly in Goal 15 of the Sustainable Development Goals to be achieved by 2020, in the Global Objectives on Forests of the United Nations Forest Instrument, and in the Aichi Biodiversity Targets of the Convention on Biological Diversity.

The agreement under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) to reduce GHG emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (known as REDD+) is a potential source of incentives for developing countries that could be used to reduce forest degradation (and related GHG emissions) and to restore or otherwise improve the management of forests (thereby increasing forest-based carbon sequestration).

What is the role of forest managers?

What is the role of forest managers?

Forest degradation is a global challenge, and it should be addressed at all levels (local, subnational, national and international). It is often the consequence of unsustainable forest management, the excessive exploitation of forest resources, and factors outside the specific forest area being managed. Forest degradation may be considered as a signal to alert us that sustainable forest management (SFM) is not being achieved.

It is difficult to implement SFM when the enabling conditions for SFM – that is, conducive policies, governance regimes, institutions, incentives, regulations, tenure, rights, transparency and stakeholder engagement – are absent. Forest and land managers can advocate for an enabling environment for SFM, and they can be key actors in halting and reversing forest degradation through their local-level actions.

The most important thing that forest managers can do is to adhere to the principles of SFM in their management approach, with the aim of ensuring that today’s uses and practices maintain and enhance the economic, social and environmental values of forests in perpetuity while also providing appropriate livelihoods. More specifically, forest managers should define and apply sound management plans, define and respect harvesting limits, monitor and detect signs of forest degradation and environmental impacts, and take appropriate and timely measures to halt or reverse degradation – including by requesting assistance and technical support when needed.

In forests under SFM, forest managers should regularly monitor the effects of management practices and assess whether they are causing degradation (see the Forest Management Monitoring module). SFM is a dynamic process, and forest management plans and practices should be adapted over time in light of monitoring and assessment and evolving economic, social and environmental conditions (see the Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation module).

Forest degradation is best addressed by a comprehensive approach aimed at its direct and underlying drivers. The table provides examples of technical actions that can help prevent or halt forest degradation.

Examples of undesirable effects leading to forest degradation | Examples of actions to arrest forest degradation |

Reduction in site productivity | - Modify sustainable annual harvest |

Limited regeneration after logging | - Put in place practices to help forests recover after harvesting (e.g. assisted natural regeneration, enrichment planting) - Avoid reducing the population of any tree species to the extent that self-replacement is not possible (e.g. maintain a sufficient number of seed trees) - Modify logging practices to avoid future degradation |

Soil erosion | - Reduced impact logging - Mulching to improve soil conditions - Measures to maintain and improve the growth of groundcover vegetation |

Impact on wildlife populations | - Measures to reduce the impact of logging activities on local fauna (e.g. respecting reproductive periods) - Maintenance of connectivity across forest landscapes - Appropriate land-use planning |

Presence of pests | - Ensure that good practices are applied correctly (e.g. control entry pathways – see the Forest Pests module) |

Forest encroachment for agriculture/livestock | The following actions may be beyond the scope of forest managers and require the involvement of other land managers and actors: - Land-use planning - Promotion of sustainable practices - Promotion of alternative livelihoods - Law enforcement, awareness-raising and capacity building |

The Silviculture in Natural Forests module provides additional information.

When forest degradation is the result of natural causes such as storms, droughts, pests or wildfires, forest managers should aim to strengthen forest resilience so that stands are better prepared for future events. This can be done, for example, by maintaining biodiversity at varying forest scales (e.g. stand, landscape and region); applying integrated fire management (mainly risk reduction and recovery); applying integrated pest management; and (in planted forests) selecting tree species and varieties likely to be resilient in the face of expected future conditions (see also the Forestry Responses to Natural and Human-conflict Disasters module).

Forest and land managers can reverse degradation by restoring and rehabilitating forest landscapes (see Forest Restoration and Rehabilitation module) and through appropriate land-use planning.

In order to do so in a way that is efficient for the community and the environment, both men and women forest managers must take gender considerations into account. Overall, the degradation of forests affects men and women differently. In rural areas, a woman’s life is fundamentally dependent on nature, since she has to maintain her family by managing and using natural resources (e.g. women are primary providers of household food, fuel and water for cooking, heating, drinking and washing). Climate and biodiversity alterations caused by forest degradation largely hinder women’s livelihoods.

When assessing forest conditions and planning a reverse degradation project, forest managers must consider women’s needs, as well as the role they play as mitigating agents. If trained and empowered, women can lead the fight against degradation. They have a very close relationship with forests and trees and can recognize the undesirable effects of forest degradation such as soil depletion, reduced productivity and regeneration, and the presence of pests. This knowledge can be applied to adopt mitigation measures. For instance, composting kitchen waste may provide soil-enriching fertilizer. Since women know the life cycles of the trees and plants, they are inestimable resources for land use planning, especially when it comes to sustainable harvests, seed conservation and maintenance.