Over the past few decades, the rate of growth of world population has shown only a slight tendency to slow down, but this trend, i.e. a decline in the growth rate, is expected to accelerate in the coming decades, both in the developing and developed regions (table 1; Kennedy, 1993; UN-ECE/UNFPA 1992 and 1992a; UNFPA/UNPF, 1993). Growth rates in the developing regions have been more than three times higher than those in the developed - 2.3 and 0.7 percent a year respectively between 1970 and 1990. In terms of numbers, the increase in developing countries' populations has accelerated - from 48 million a year between 1950 and 1970 to a projected 91 million a year between 1990 and 2000 - and the growth in numbers begins to decelerate only in the next century. Europe's population is expected to grow more slowly than any other region's, and its share of world population will be only 6.1 percent in 2025 compared with 9.4 percent in 1990.

The main reason for the slowing down in Europe has been the decline in fertility rates (number of children per woman of reproducing age), which have even fallen in some countries below the replacement rate (UN-ECE/Council of Europe/UNPF, 1993b and 1993c). Lengthening life expectancy has only partly offset this trend. The effect of these two trends is for the age structure of populations to shift towards older average ages. The projections to 2025 are also based on certain assumptions regarding net migration, which in the case of Europe can be the subject of considerable doubt. They also build in the “carry-on effect” over several generations of the post-Second World War “baby boom”.

Table 1: Estimates and projections of world population, 1950 to 2025

| 1950 | 1970 | 1990 | 2000 | 2025 | |

| Total (million) | |||||

| World | 2516 | 3698 | 5292 | 6261 | 8504 |

| - Developing countries | 1684 | 2649 | 4086 | 4997 | 7150 |

| - Industrialised countries | 832 | 1049 | 1207 | 1264 | 1354 |

| *Europe | 393 | 460 | 498 | 510 | 515 |

| Average annual increase(million) | |||||

| World | 59.1 | 79.9 | 96.9 | 89.7 | |

| - Developing countries | 48.3 | 71.9 | 91.1 | 86.1 | |

| - Industrialised countries | 10.8 | 7.9 | 5.7 | 3.6 | |

| *Europe | 3.3 | 1.9 | 1.2 | 0.2 | |

| Average annual increase(percent) | |||||

| World | 2.0 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.3 | |

| - Developing countries | 2.4 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 1.5 | |

| - Industrialised countries | 1.2 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.3 | |

| *Europe | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.04 | |

| Share of world total(percent) | |||||

| - Developing countries | 66.9 | 71.6 | 77.2 | 79.8 | 84.1 |

| - Industrialised countries | 33.1 | 28.4 | 22.8 | 20.2 | 15.9 |

| *Europe | 15.6 | 12.4 | 9.4 | 8.1 | 6.1 |

Source: UN Population Division, World Population Prospects 1990

Fertility rates are largely determined by cultural and social factors, which have been changing rapidly throughout the region. Improved education, reduced inequality between the sexes and higher proportions of married women in employment tend to lower fertility rates. On the other hand, the existence of child allowances and of child care facilities, which are generally better in the northern part of Europe than in the south, tend to raise these rates. Thus, the fertility rate in Sweden is twice that in Italy. Improved medical care largely explains longer life expectancies that are common to all countries. One European country where birth rates have been and are likely to remain high is Turkey, which will become the most highly populated country in the region by the early decades of the next century.

Europe was a net exporter of people in the 19th and first part of the 20th centuries. Since the Second World War, this trend has been reversed, and net immigration into western Europe has been a factor in the continuing rise in populations (Appleyard, 1992). In the late 1980s and early 1990s, pressure of immigration, notably from North Africa and other developing areas, has increased markedly, principally of migrants seeking employment and better standards of living. A quite recent phenomenon has been the build up of migration pressure from some of the countries in transition of central and eastern Europe towards the west for the same reasons and in a few cases, as in former Yugoslavia, to escape from internal turmoil. Pressure is also increasing westwards from parts of the former USSR.

The pattern of migration within and to Europe since the Second World War has been complex, with several different directions of flow at different times and often reverse flows as employment situations have changed in the receiver or sender countries. Migration has been generally beneficial to the receiving countries in providing labour, particularly for the less attractive jobs, but has recently been accompanied by increasing problems of assimilation and social tensions (OECD, 1993b). Emigration's net effect on the sending countries is uncertain. It can be beneficial when part of the wages is returned for the support of families left behind and when skilled workers return home to work, but it can also contribute to a “braindrain” and to an acceleration of rural depopulation.

Internal migration within European countries has been significant during the 19th and 20th centuries, with urban populations accounting for an increasing share of the total at the expense of the countryside. The reasons have been much the same as for international migration: the prospect of jobs and a better standard of living; but the mechanisation of agriculture and decline in jobs on the land have also played an important role. In the industrially most advanced countries, the movement of people to towns and cities has slowed down and even sometimes been reversed as a result of several factors, such as a narrowing of living standards between town and country, improved rural infrastructure, and congestion and social tension in cities. In countries with a still relatively high rural population, as in much of southern Europe, migration continues and is leading to rural depopulation with accompanying economically and socially negative consequences for the more remote and poorer areas.

Household formation and changes in the number and structure of households is also a complex issue, affected by such factors as changes in frequency and age of marriage and child-bearing, divorce, number of single-parent families, longevity, etc. Generally speaking, households are tending to become smaller in Europe as a result of having fewer children, increasing divorce rates and longer life expectancy.

Alleviating unemployment, as well as its impact on the financing of social security, has become a major political concern in virtually all western European countries during the early 1990s (OECD, 1992c). While mainly linked to the deep and persistent recession in the region and therefore likely to prove to have been partly of a cyclical nature as economic expansion gets under way again, there is also a structural and therefore long-term element involved, arising from a number of causes. These include declines in activity in some of the traditional, more labour-intensive industries, the continuing and even accelerating process of technological development and raising productivity in all sectors of the economy, and the transfer of some industries to regions with low costs even for skilled labour, such as South-East Asia. As regards the countries of central and eastern Europe with economies in transition, the restructuring of their economies, involving the closure of some industries and the raising of efficiency in the remaining ones, is also leading to growing unemployment, a phenomenon which was previously largely hidden by over-manning practices.

In western European countries, Governments are under pressure from labour unions to take measures that would maintain industries in operation in order to save employment and to support re-employment through retraining, job creation, etc. Europe seems generally to have been less successful than the United States in creating new jobs. Workers and unions have been less willing to lower social support standards, and this has been one reason for higher labour costs and loss of competitivity. Also, people in Europe have tended to be rather inflexible in their willingness to change one occupation for another and to move to new areas. This may be due partly to traditional attitudes, partly to the level of welfare support in many countries which may even lead workers to prefer unemployment to the uncertainties of change. This attitude may be gradually changing, as countries are having to consider reducing levels of welfare support, including unemployment benefits.

Health and education are other factors that are of major importance in themselves, but do not appear to require detailed consideration for the purposes of this study. This assumes that, in the case of health, no major change occurs in the general tendency in Europe for health standards to improve, for example that AIDS or some other health scourge does not cause a significant shift in population trends, as may happen in parts of Africa and Asia, for instance. Educational standards in Europe have generally been improving, with an increasing proportion of young people taking higher education, leading in turn to greater expectations for professional employment and living standards, not always fulfilled. On the other hand, the declining birth rates are leading in many countries to reduced need for education facilities, a feature which can be especially marked in rural areas with shrinking populations. Both health and education are major drains on national budgets. Nevertheless, it is recognised that education is essential if sufficient qualified labour is to remain in order not to lose the competitive edge vis-à-vis other countries, such as the emerging economies of Asia.

European countries' demographic policies will be concerned with adapting to, and in some cases also seeking to influence, the slow down or halt in population growth and the consequent impact on the age distribution and related problems. Few, if any, European countries are likely to countenance an overall reduction of their populations. On the other hand many, especially those with already high population density, may accept slow or negligible growth, provided this occurs without serious adverse consequences for employment, the social security services, etc. Adaptation to changes in population structure will include such measures as improving the relationship between those contributing to the welfare and social support systems, principally the employed, and those dependent on support of one kind or another, the proportion of whom is expanding and therefore putting increasing strains on the system. One option is to increase retirement age; another to shift more responsibility for welfare support from the state to the individual or private enterprise. Asking the actively employed to contribute more is another possibility, but given their declining share of total population, this would create new problems.

The changes in household structures, notably the trend towards smaller households and a rising proportion of single people, mainly elderly, and single-parent families, require policies to adapt the type of housing available to the population. This will be discussed later in Section 2.9 on construction, which will also consider related aspects such as changes needed in infrastructure and services, and the location of housing.

Fewer children per family will lead to a decline in the number of young people entering the workforce and the possibility of the present over-supply (unemployment) of young people seeking jobs in the majority of European countries giving way, as economic recovery takes place, to labour shortages, especially in the lower paid, less skilled and less attractive fields of work. These jobs will often be filled by immigrant workers. There are differences of opinion on the extent to which the current high levels of unemployment are a cyclical problem, which will evaporate with economic recovery, or are the more profound and lasting consequences of the tremendous gains in productivity through technological advances. These lead to structural long-term unemployment, affecting virtually all types of employment, professional and other, and their location. Either way, measures to tackle unemployment will remain high on the policy agenda of many countries during the 1990s.

It has been suggested that the costs of providing social security, together with regulations governing minimum wage levels, are factors affecting some countries' international competitivity. It may indeed be that they have the effect of raising the cost of marginal operations, a point that will need to be taken up to when considering the impact on certain forest operations and wood processing industries.

With regard to migration, several west European countries find themselves in a dilemma (UN-ECE/Council of Europe/UNPF, 1993). On the one hand, the development of the Single Market in Europe should lead to the opening of frontiers to movements of labour, as well as goods and capital. On the other, they are having to adopt more restrictive positions on immigration, partly in response to unemployment and partly to their concern about the problems of assimilation. There is recognition of the need to bring in some labour to carry out certain types of work, which domestic labour is reluctant to do, or to fill gaps in specific skills. Largescale migration may not be in the long-term interests of either the sending or receiving countries, and measures to encourage people to stay and work in their own countries are being considered, for example investment by countries with immigration problems in the sending countries, coupled with technology transfer and training (Appleyard, 1992). This may be particularly relevant in the case of countries with economies in transition of central and eastern Europe. The latter countries' moves, after the political changes in 1989/90, to allow the freer outward and inward movement of people also represents a significant policy change on their part. At the same time, it can be expected that growing imbalances in population numbers and welfare services between western Europe and neighbouring regions, notably North Africa, but even between parts of Europe, will generate tensions and pressures affecting European policies.

Policies already exist in many countries relating to migration from the countryside to urban areas, but will no doubt be further refined in efforts to retain and improve the social and economic fabric of less favoured and remote areas. Mountain areas are particularly affected by the trend (Stone, 1992). These will include support for improvements to infrastructure and services, such as schools and medical facilities, as well as for better housing in rural areas. At the same time, problems of an increasingly urbanised society, including overcrowding, traffic congestion and social tensions, amongst others, will have to be tackled in more and more cities.

Many of the implications of demographic issues for the FFI sector are indirect, in that they have an impact first of all on another policy sector. This is the case for example of changes in age distribution and in household formation, which affect the amount and type of construction, and hence the demand for forest products. Rather than discuss the impacts in detail in this chapter, attention is drawn to them briefly below, with cross-reference to the chapters where they are dealt with more fully. Here, and in subsequent chapters, the impacts on the four parts of the FFI sector, specified in Section 1.3, are considered separately.

Forest resources, forestry and wood supply

Forestry, including afforestation, and wood harvesting, may be one of the measures used to try to slow

down or reverse the drift from country to city by providing rural employment. This by itself may not be

enough to justify investment in forestry but can be added to others that are discussed in Sections 2.5,

2.6, 2.7 and 2.10 on land use, rural and regional development, agriculture, industry and the role of the

public sector, respectively. One major problem to be addressed is the attractiveness of forestry as a

vocation or profession. In many countries, the average age of forest workers has been rising and

difficulties have been encountered in recruiting young people into what is seen as a low paid, physically

hard, sometimes dangerous occupation with a poor social status. Some countries have overcome the

problem by mechanisation, technical training, use only of full-time workers and the giving of increased

responsibility to personnel. While this may have considerably raised pay scales and reduced the physical

input required, the corollary has been a steep fall in the number of forest workers employed through

greatly increased productivity. While unavoidable, this may have been counter-productive to policies of

maintaining rural employment.

Wood-processing industries

Policies to locate certain industries close to sources of raw material, such as small-to-medium-sized

sawmills and wood-using enterprises, including artisan workshops, will also be discussed in later

sections. It may be noted here that these can contribute to rural employment and, in the case of

handicrafts, help to attract tourism to rural areas and provide additional sources of revenue.

International trade in forest products

Policies to assist developing countries and those in transition to a market economy through investment in

industry, for example joint ventures, may include elements of self-interest on the part of the fund-providing

countries in that they would reduce migration pressures by supporting employment in the

emigration countries. Part of the output from such employment will be directed to domestic markets. The

fund-providing countries, however, should expect that some countries that they assist in this way,

whether European countries with economies in transition or countries in developing regions, will also

have to find export markets, and that accordingly they must be prepared to allow easier import access.

This will be considered in sections 2.7 and 2.8 on industry and trade.

Markets and demand for forest products

Changes in the number and structure of the population will have a direct impact on forest products

consumption. So far as numbers are concerned, this can be built into projection models through the

relationship between per caput consumption and other parameters, such as per caput GDP. The impact

of structural changes on consumption is less easily quantifiable (unless very detailed data are available),

but is nonetheless important to take into consideration. Two aspects in particular will be looked at in the

Section 2.9 on construction: the tendency in many European countries for the number of households to

increase as a result of longer life expectancy and more single-parent families, but for the average size of

households to shrink; and the movement, marked in some countries with still relatively large agricultural

sectors, as in southern and eastern Europe, of people from rural to urban areas. Conversion of the

existing housing stock may play a more important role than new building, although the latter may be

required for certain specific needs, such as shelter homes for the elderly. A return of the building boom

of the 1950s and 1960s, which was required to replace war-damaged stock, is not to be expected except

locally, for example in parts of the former Yugoslavia.

Economic growth in Europe since the end of the Second World War has been in two distinct phases (UN-ECE, 1991a). The first, up to the early 1970s and culminating in the oil price shock of 1973, was marked by average annual economic growth higher than during any previously recorded period. This marked expansion was partly generated by the post-war process of reconstruction and recovery. The second period, lasting from 1973 to the present, has witnessed slower average growth and sharper cyclical movements, marked by alternating periods of high inflation and unemployment and currency disturbances. One of the principal causes of these more unstable conditions has been the greater share of public spending in total Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and the tendency for public sector deficits to mount.

At the world level, GDP growth during the 1980s was appreciably less than in the 1970s - 2.9 percent a year on average compared with 3.8 percent - with the slowing down equally marked in the industrialised and developing countries on average (table 2), although among the latter, some areas such as South-East Asia continued to show dynamic growth. World Bank medium-term projections give a similar rate of growth worldwide during the 1990s, with a further slight deceleration in the industrialised countries being offset by an acceleration in the developing regions, which continue to account for a growing share of the world economy. Despite the faster GDP growth in the latter, the discrepancy in economic welfare (in terms of per caputGDP) between the rich and poor regions hardly changes over the 20-year period. The ratio between average per caput GDP in the industrialised and developing countries was 10.3 : 1 in 1980, 11.0 : 1 in 1990, and a projected 10.0 : 1 in 2000. This is a consequence of the much faster growth in population in the developing regions, as described in the previous chapter.

| Total GDP | Total at 1980 prices | Average annual change | ||||

| 1980 | 1990 | 2000 | 1970–1980 | 1980–1990 | 1990–2000 | |

| (billion US $) | (%) | |||||

| World | 11562 | 15415 | 20816 | 3.8 | 2.9 | 3.0 |

| - Industrialised countries | 9095 | 11914 | 15146 | 3.4 | 2.7 | 2.4 |

| - Developing countries | 2467 | 3500 | 5670 | 5.5 | 3.6 | 4.9 |

| Per caput | (US $) | (%) | ||||

| World | 2599 | 2913 | 3324 | 1.9 | 1.1 | 1.3 |

| - Industrialised countries | 7783 | 9544 | 11519 | 2.5 | 2.1 | 1.9 |

| - Developing countries | 752 | 865 | 1146 | 3.2 | 1.4 | 2.9 |

Source: FAO, Medium-term prospects for agricultural commodities: agricultural commodity projections to 2000 (CCP 93/18, March 1993). Based on World Bank projections.

At the present time there is great uncertainty about the future course of the world economy - but when has there ever not been? Doubts about such major influences as the outcome of the GATT Uruguay Round negotiations (now satisfactorily completed apart from formal ratification), western European integration, the process of transition in the countries of central and eastern Europe and notably the former Soviet Union, monetary instability and rising public sector deficits, to mention only some, make it very difficult to look into the future. This is reflected in the alternative growth scenarios to the year 2015 in table 3 (Central Planning Bureau, Netherlands 1992; UN-ECE, 1993d). Depending on the assumptions used, GDP growth in western Europe, for example, could vary between 1.9 percent and 3.2 percent a year over the 25-year period; and an even greater variation is shown for the transition countries: from minus 1.6 percent in the “global crisis” scenario to plus 2.7 percent a year.

| Scenario:a | “Global shift” | “European renaissance” | “Global crisis” | “Balanced growth” |

| World | 3.4 | 2.9 | 2.4 | 3.6 |

| - North America | 3.4 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 3.0 |

| - Western Europe | 1.9 | 2.8 | 2.0 | 3.2 |

| - Central Europe & CIS | 0.2 | 2.3 | -1.6 | 2.7 |

| - Japan | 4.3 | 3.7 | 3.5 | 3.1 |

Source: Scanning the future: a long-term scenario study of the world economy 1990–2015. Central Planning Bureau, the Netherlands, 1992.

a It is not possible to summarise in a few words all the assumptions underlying the four scenarios. To give an indication,however, the “Balanced growth” scenario is characterised by, inter alia, a global transition to sustainable growth, integration in western Europe based on market forces, and very competitive world market structures resulting from a breakthrough in GATT negotiations. This is the most optimistic of the four scenarios at the global level, though not for all the regions.

There can be a risk that perceptions of medium - to long term prospects may be biased by the current situation. Care may need to be taken, therefore, not to exaggerate the impact of the depressed state of the economy in Europe, both west and east, during the early part of the 1990s. In western Europe, 1993 was the third year running in which little or no growth has occurred. For most of that time, policies in many countries were aimed primarily at reducing inflation and correcting the spending excesses, both public and private, of the 1980s. The inevitable result was a slowing down in growth and increasing under-utilisation of resources, notably labour. Unemployment increased considerably and by mid-1993 had replaced inflation as the primary concern of many governments. Consequently, policies in most western countries have been directed towards stimulating economic activity again through lower interest rates and other measures.

Germany has found itself in a special situation arising from the heavy costs involved in converting and integrating the former German Democratic Republic into the rest of the country's market economy, which has meant that it had greater difficulty in bringing inflation under control than most of its neighbours. Despite the underlying strength of the German economy, it may therefore pull out of the present recession more cautiously than other western European countries and, because of its economic weight, this may act as a brake on the region's recovery.

The extraordinary, and totally unexpected, developments in central and eastern Europe, including the former Soviet Union, in 1989 and 1990 constituted a major turning point in Europe's history (UN-ECE, annual (a)). The peoples of these countries made it clear that they wanted a radical and decisive change in the way their political and economic affairs were conducted. All of them have been moving from single-party government and centrally controlled economies towards pluralistic political systems and decentralised, market economies, although recent events in some of them have raised doubts about the pace and extent of restructuration.

The immensity of the problems involved in this transition process was not immediately apparent, either to the countries themselves or to those that sought to assist them. Early euphoria gave way to sombre awareness of just how dilapidated the economies had become, the sacrifices that would have to be made to bring about the transition and the timescale that was likely to be needed. Not only was the industrial and infrastructural base badly run down, but the whole social, economic and commercial framework which is taken for granted in a normally functioning market economy was almost entirely lacking. On top of that, the mental adjustments to be made at all levels of society, but particularly among managers, from a system of central planning and decision-making to greater personal responsibility have proven to be difficult in many cases.

The problems to be overcome and their scale varied from country to country, as have the paths chosen to introduce stabilisation programmes and to relaunch the economies. Some countries, such as Poland, Czechoslovakia and Bulgaria, followed the “shock therapy” approach, while others, such as Hungary adopted a “gradualist” one (OECD, 1993f). Choice of the path of reform was partly based on the prevailing conditions, for example the threat of hyper-inflation in some countries required a strong and rapid response to avoid complete economic collapse.

Whatever the means chosen to move towards a market economy, the immediate result was a sharp decline in economic activity in all the transition countries, mainly through reduced industrial output as obsolete factories found themselves unable to compete or to switch to the quality or type of product demanded by the market. As will be seen in Section 2.6, agricultural output also fell substantially. Between 1989 and 1992, the cumulative drop in output in eastern Europe amounted to about 30 percent, although by the end of the period there were signs that the down turn was levelling out and that in a few countries, notably Poland, a recovery had started. Whatever the remainder of the 1990s may hold in store for the countries with economies in transition, their progress should be viewed from the depressed levels to which their economies fell during the initial phase of transition, rather than the unsustainably high levels reached in the late 1980s.

The closing of obsolete and uncompetitive industries, spreading privatisation and introduction of bankruptcy laws is leading to rising unemployment in the transition countries, some of which still have not set up the social security systems needed to deal with such problems. This, and the low wages in these countries, largely explain the pressures to emigrate which were described earlier. In several countries, privatisation of small enterprises, such as shops, services and small industries, has been moving ahead quite rapidly, but much greater difficulties are having to be overcome in the privatisation of the large enterprises. This will be given further consideration in Section 2.7 on industry.

Among the major policy directions that will continue to be followed in west European countries will be efforts to minimise inflation, to reduce public expenditure and public deficits, to improve fiscal balances and, partly as a means of achieving those objectives, to pursue privatisation. In countries with economies in transition, the moves towards liberalisation of exchange rates and prices, and privatisation of economic activities, have been of particular importance in recent years, and are likely to be persisted with in the coming years.

Closer economic integration has been an objective of all western European countries, with the twelve members of the European Community (EC) in the vanguard. Steps have included the setting up of a Single Market within the EC, which came into effect on 1 January 1993, and of the European Monetary Union (EMU) and Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM), the latter having the aim of improving monetary stability between countries and thereby providing a firmer basis for economic development. The Maastricht Treaty, which was finally approved and ratified by its signatories in 1993, seeks to take the integration process further, for example by the eventual introduction of a single currency within the EC. Serious disturbances in the exchange rate markets in autumn 1992 and again in summer 1993 underlined the difficulties involved in this process, and it now appears possible that the original timetable for establishing the EMU may have to be postponed.

Other initiatives have included the move towards a European Economic Space, which would eliminate trade barriers between the EC and the six countries of the European Free Trade Area (EFTA). One EFTA member, Switzerland, through a referendum in November 1992, has opted out of this scheme for the time being. Several of the EFTA member countries (Austria, Finland, Norway, Sweden) have negotiated with the EC for full membership and one or more of them will join in January 1995. The EC has negotiated agreements with several of the transition countries of central Europe to improve economic cooperation and access to markets, and is negotiating with others. While the principle of closer integration is accepted by all countries, events of the past few years have shown that national considerations, such as the protection of industries, agriculture and employment, still tend to take precedence, especially in times of recession. This was evident in the struggles to conclude the GATT Uruguay Round of trade negotiations, in which agricultural issues were one of the main stumbling blocks.

Policies in all European countries will continue to be directed towards raising the economic well-being of their peoples, particularly in those countries that are economically less developed, that is to say in southern and eastern Europe. This will be achieved by aiming at continuing growth of the economy at average rates that will not cause over-heating but will ensure the optimum use of resources, notably labour. In practice, steady long-term growth has proved impossible under market economy conditions, which have been characterised by cycles of roughly 5 to 7 years during the post-war period. Policies have therefore attempted to “manage” the cycles with the intention of limiting the negative consequences of both the upward and downward swings. The instruments mainly used have been monetary and fiscal.

The huge cost of reunification in Germany has up to now been largely financed by borrowing through the maintenance of interest rates at levels that would attract the necessary funds (and adding to the public debt). This was a major factor behind the strains on the international money markets in the summer of 1993.

Indicators such as per caput GDP describe reasonably well the economic standard of living of the population, but are of limited use to measure the quality of life, since they incorporate only some of the social and virtually none of the environmental factors that determine the latter. While it is probable that western European countries will generally maintain existing policies towards economic growth in the future, they will increasingly seek ways to achieve such growth within the broader context of “sustainable development” (see Section 2.4 on environmental policies). This will include considerations for the quality of life, including the protection of the environment and the safe-guarding of natural resources for use by future generations. This does not necessarily mean slower economic growth than in the past, but rather a different type of growth based on certain criteria which have not been adequately recognised up to now.

This will also be true for other parts of Europe but, as shown earlier, the situation in the countries in transition is special. They are today facing some of the same challenges that western Europe had to face after the Second World War (Slater, 1993; UN-ECE, 1990). In some respects their position is better: they have a well-educated workforce, for example. In others, they are less fortunate, notably in the lack of the institutional and commercial infrastructure needed to make a market economy function. Until such a framework is established, it will be difficult for the transition countries to make progress on the modernisation of their economies and industries, including privatisation. Estimated vary of how long it may take the countries with economies in transition to approach the levels of the “old” market economy countries and, of course, it will be different for each of them. Hungary, for example, may make relatively quick progress. One guess that may not be too unrealistic is that it will take a generation for the transition countries as a whole to more or less catch up with western Europe.

Economic developments are fundamental as determinants of the evolution of the FFI sector, as is evident from the correlation between changes over time in GDP and consumption of forest products. These are incorporated in the models used in ETTS V for projecting the demand and supply of forest products, and there is no point in discussing here the assumptions underlying the GDP explanatory variables used in the models. There are, however, a number of less tangible economic issues, and the policies that address them, which should be touched on, either here or, because they have an impact firstly on another sector and only secondly on the FFI sector, in later sections.

Forest resources, forestry and wood supply

Decisions on the management of the forest resource and on wood supply are affected by the overall

economic environment, but generally as a secondary effect. Sustainable development is a case in point.

Measures to redirect growth onto a more sustainable path will involve adaptation of economic policies to

incorporate environmental and energy saving concerns, amongst others. The impact on forestry will be

discussed in the appropriate sections. Generally speaking sustainable development requires the optimum

allocation over a long period of time of renewable and non-renewable resources, with the emphasis

shifting towards renewable resources, of which wood is on the most important, both as a primary raw

material and as a source of energy. The timeframe of ETTS V may be too short to see a major impact

on wood availability of changes in policies to favour renewable resources, but some effects on the forest

resource itself may already become apparent, for example through fiscal measures to encourage the

intensification of silviculture and expansion of forest area (see Sections 2.6 and 2.10 on agriculture and

the role of the public sector, respectively). Similarly, policies, and the economic measures taken to

implement them, related to climate change and the checking of CO2 emissions from the burning of fossil

fuels (see Section 2.3 on energy), which also are relevant to sustainable development, could have a

positive impact on the forest sector before the end of the ETTS V timeframe.

Wood-processing industries

These industries, in common with those in other sectors, will be strongly affected by the rate and extent

of economic integration in Europe, as well as by policies relating to employment, trade, regional

development, which are dealt with in later sections. Present moves towards closer integration will lead to

increasing international competition, requiring constant efforts to raise productivity through better

economies of scale, use of modern technology and improved production management. The wood-processing

industries, with the exception of parts of the pulp and paper sector, consist of small and

medium-size enterprises, often under-capitalised and labour-intensive. The number of smaller

enterprises, particularly sawmills, has been declining in all countries, and this process will continue.

Nevertheless, quite a number will survive, notably those that are able to serve “niche” or local markets or

are able to integrate forwards or backwards to secure markets or sources of raw material. Larger mills

will account for an increasing share of total output of the various assortments of processed wood

products. The extent of integration will largely determine their location, since this will depend on

economic considerations uncluttered by problems of trade barriers.

The great uncertainty regarding economic development in the countries with economies in transition makes it difficult to comment on the likely impact on their wood-processing industries. Most of these are at present suffering from the handicap of obsolescence and low productivity and from grave problems in attracting the capital required for modernisation. The economic conditions needed to do this would have to include greatly improved prospects on the domestic and export markets, in which circumstances capital as well as technical know-how would no doubt be attracted from abroad.

International trade in forest products

This will also be dependent on the pace of economic integration. The present 12-member EC is roughly

50 percent dependent on imports to meet its consumption of forest products, whilst three of the EFTA

countries, Sweden, Finland and Austria, are Europe's leading exporters. Creation of the EEA would

accelerate the rationalisation of the west European market in forest products, which is in fact already

rather open and free from high trade barriers. There has also been a process of “internationalisation” of

the European forest products industry through acquisitions and mergers, with the industries of northern

Europe becoming especially active in the EC. This process will extend into other parts of Europe,

notably the countries with economies in transition.

The net effect on the pattern and volume of trade, both intra- and inter-regional, in forest products is not easy to predict. Europe's exports and imports as a share of production and consumption, respectively, have remained rather stable over the past decade or so in volume terms. For sawnwood, imports' share of consumption has even declined as sources of raw material and the means to process them have increased in some of the importing countries, such as France, Ireland and the United Kingdom. Bearing in mind the greater competitive pressures created by integration, it may be reasonable to expect that certain bulk-product industries, such as pulping, may become more concentrated near areas with large forest resources, while the further processed products, including some grades of paper and furniture, will be produced closer to the main markets. This would imply a higher proportion of total trade in semi-processed products, such as sawnwood (including dimension stock, furniture parts, etc.) and woodpulp, although not necessarily in wood raw materials because of the high cost of transportation in their total delivered price.

Markets and demand for forest products

Trends in demand for paper and paperboard, of all the forest products, are most closely correlated with

those of the economy as a whole under market economy conditions. As the transition countries move

towards a form of market economy, it is likely that their present low per caput consumption levels of

paper and paperboard will rise strongly, partly also as a result of the removal of the previous supply and

demand constraints, for example, systems of centralised allocation of resources and the barriers to the

exchange of information. For consumption of these products throughout Europe, the longer term

prospects are linked with those of economic growth, although this needs to be qualified by the possibility

that certain developments that are discussed later, including competition with electronic information

exchange (Section 2.7 on industry) and steps to reduce waste and increase recycling (see Section 2.4

on environment) may steadily reduce the income elasticity of these products. To some extent this

possibility may be covered in ETTS V's demand projections, but will need to be carefully reviewed.

Demand for the other main products, sawnwood and wood-based panels, is more closely associated with the construction sector and its ancillaries such as furniture, shop-fitting, etc., than with the overall economy. In fact the correlation with GDP growth has become increasingly weak over the past decade or so. Further discussion is postponed to Section 2.9 on construction.

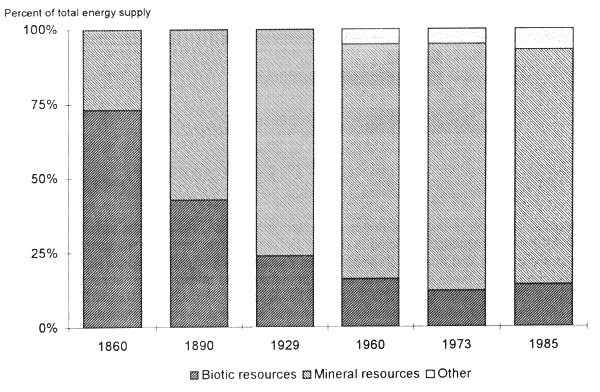

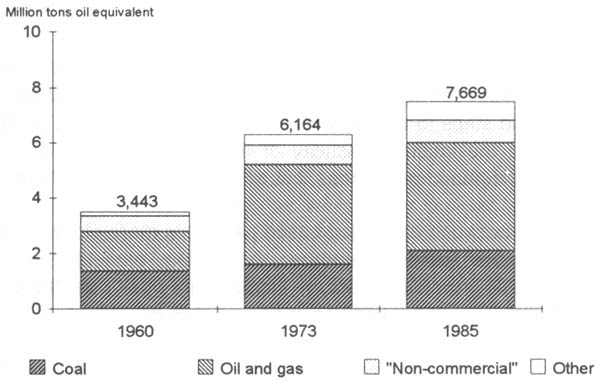

Historically, growth in the use of energy has been closely associated with that of the overall economy, despite considerable changes over the long term in the composition of the sources of energy and the pattern of use (Cohen, 1992). The linkage between GDP and energy use has been considerably modified in recent decades, however, and this will continue in the future. With regard to sources, it is estimated that in the middle of the 19th century, three quarters of world total primary energy supply (TPES) originated from biotic matter, for the most part wood, while a quarter came from mineral resources, principally coal (figure 1). A hundred years later the roles had been reversed, with fossil fuels (coal, gas and oil) accounting for over 80 percent of the total. A feature of energy supply in the past 30 years or so has been the trend towards diversification, with alternatives to fossil fuels taking up an increasing, but still minor share. In figure 2, “non-commercial” sources are mainly biomass, while “other” sources include nuclear and hydropower, as well as minor supplies from solar, wind, etc. In 1985 three quarters of TPES was still supplied by fossil fuels.

Figure 1: Share of different categories of natural resources in global energy supply, 1860 to 1985

Source : Int. Journal of Global Energy Issues, Vol. 4, No 4, 1992 (Table 4)

Figure 2: World primary energy consumption 1960 to 1985

Source: Int. Journal of Global Energy Issues, Vol.4 no 4, 1992 (Table 1)

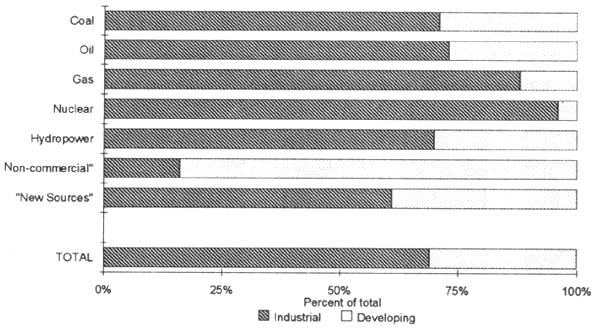

The industrialised countries account for the bulk - about 70 percent in 1985 - of world primary energy consumption, but the share varies considerably according to the type of resource. While the industrialised countries use the major part of the total of coal, oil, hydropower, and particularly of nuclear and gas, the developing countries use 85 percent of the “non-commercial” resources (wood, agricultural waste ) and over 40 percent of “new sources” (figure 3).

Figure 3: Share of industrialised and developing regions in primary energy consumption by category, 1985

Source: Int. Journal of Global Energy Issues, Vol. 4, no 4, 1992 (Tables 2 and 3)

This distribution of supply is closely related to the pattern of use (IEA, 1992). In the developing countries, a large part of the total, although declining in relative but not absolute terms, is still absorbed by domestic households for cooking and heating. Taking western Europe as an example (figure 4), the industrialised regions use around two thirds of their final energy in industry and transport, and about one third in other sectors, which include households, shops, public services and agriculture. Comparable data are not available for the transition countries, but it would seem that a larger proportion of the total has been used by industry and a smaller part by transport than in western Europe.

Figure 4: Final energy consumption by sector in western Europe, 1973, 1979 and 1990

Source: Energy Policies of IEA countries 1991 Review

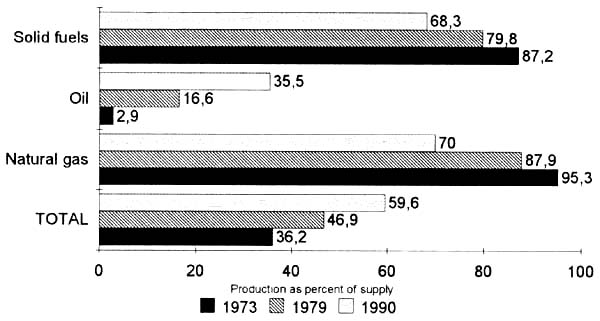

Self-sufficiency in energy has become an important policy issue, especially since the oil price shocks of the early and late 1970s, which underlined the potential vulnerability of the industrialised countries to disruptions in their oil supplies from the Middle East. Since 1973, western Europe has considerably increased its self-sufficiency in oil: from 3 percent to 35 percent in 1990 (domestic production as a percent of total supply), mainly as a result of the exploitation of the North Sea oil reserves. But that in solid fuels and natural gas declined (figure 5), as imports built up form the former Soviet Union and other external sources. For fossil fuels in total, self-sufficiency improved from 36 to 60 percent over the 17-year period.

Figure 5: Development of energy self-sufficiency by product in western Europe, 1973 to 1990

Source: Energy Policies of IEA countries 1991 Review

Fossil fuels are a non-renewable resource, and policy must be concerned with ways in which they can be conserved and eventually replaced by renewable resources. The urgency of doing so depends on the extent of reserves (World Energy Council, 1993). In the case of coal, proven reserves are adequate for a century or more at current rates of depletion. For oil and gas, the situation is more complex. Exploration for new reserves is cyclical and depends, not only on the price of oil, but also on the extent of proven reserves at a given time. When these fall below about 35 years, the need is seen to step up exploration. Informed opinion is that there are still huge quantities waiting to be discovered. Nevertheless, these will be less accessible and more expensive to exploit than existing resources. Consequently, the real price of oil, and hence of energy in general, is likely to rise gradually over the long term. This, together with environmental and sustainable development considerations, will encourage governments and industries to continue to explore alternative energy sources.

The expanding use of fossil fuels has been associated with many environmental protection problems in recent decades, of which two of the most serious have been air pollution and climate change. Air pollution is caused by the emission of gases and particulates, mainly by the burning of coal and oil but also by metallurgy and other industrial activity. The two most important air pollutants are SO2and NOx, which have contributed extensively to soil degradation (acidification) and damage to fresh water systems, buildings and monuments as well as forests.

The burning of fossil fuels and other carbon-containing matter, notably wood, has caused the volume of CO2 in the atmosphere to rise from 275 parts per million (ppm) in the mid-19th century to 333 ppm in 1985 (Cohen, 1992; Cohen and Collette, 1991; FAO, 1990a; WMO/UNEP 1990 and 1990a). A number of observations may be made. Firstly, there is considerable, although not universal, consensus that increasing atmospheric concentrations of CO2 and other “greenhouse gases”, are likely to lead to a rise in global temperature, thus causing environmental damage. Studies of CO2 concentrations in ice-cores from eastern Siberia dating back 160,000 years, however, seem to show that there is no close linkage between the timing of changes in these concentrations and of changes in global temperature. This suggests that the date when the current rise in concentration may result in a temperature rise cannot be accurately predicted. Nevertheless, atmospheric CO2 concentrations have already risen above previously recorded levels, so that the consequences are unpredictable. Thirdly, even if strong measures were to be taken in the near future to replace fossil fuels with ones that do not pollute the atmosphere, the time required for adjustment would mean that CO2 concentration would continue to rise for a long time to come. One scenario based on a “business as usual” assumption results in a concentration of 550 ppm by around 2050; another based on a assumptions of lower GDP growth and a marked improvement in energy use efficiency postpones reaching that concentration by about 40 years to around 2090. The expectation of rising concentrations is therefore a fact of life, even if the consequences, and the timing of them, are still uncertain.

In the countries of central and eastern Europe, the economic system before transition began resulted in extremely wasteful use of energy throughout the economy and little regard was given to environmental protection. Energy prices were heavily subsidised, which added to the misallocation and wasteful use of resources. The steep falls in economic output since 1989, coupled with the effects of price reform and restructuring (in some cases closing down completely) of energy-intensive industries, led to significant reductions in energy consumption. Demand for energy is likely to begin a gradual recovery from the mid-1990s, with that for oil in the transport sector expected to be strongest as mobility and freight traffic increase.

Energy production in eastern Europe (not including the former Soviet Union) is limited, with low-quality coal (lignite) the most important source in most countries. Coal output has declined significantly, which has contributed to a considerable reduction in the quantity of pollutant emissions. Romania has been the only sizeable producer of oil and gas, and its output of these has also been falling. Nuclear power has been quite strongly developed, but concerns for safety and operational standards of some nuclear plants may limit further expansion plans or decommissioning of some existing plants.

Previously, east European countries were heavily dependent for oil and gas on exports at very favourable (for the importing countries) CMEA-negotiated prices from the Soviet Union. Falling oil production in the Russian Federation and the realignment upwards of its oil prices to correspond with those of the international market imposed severe strains on the economies and balance of payments of the other transition countries and forced them to diversify their sources of energy supply and to institute energy-saving measures. Because of the previously wasteful practices, scope for improvement in energy conservation is immense.

Western Europe has already made appreciable efforts to improve energy efficiency, which may be measured by changes over time in the ratio of energy supply (TPES) or consumption (TFC) to GDP, as seen from the following figures:

| Western Europe | 1973-79 | 1979-83 | 1983-89 |

| (average annual percent change) | |||

| GDP | 2.5 | 1.0 | 2.9 |

| TPES (Total primary energy supply) | 1.4 | -2.0 | 2.3 |

| TFC (Total final consumption) | 1.1 | -2.7 | 1.8 |

| TPES/GDP ratio | -1.1 | -3.0 | -0.6 |

| TFC/GDP ratio | -1.3 | -3.7 | -1.1 |

Source: IEA/OECD, Energy Policies of IEA countries, 1991 Review.

Between 1970 and 1990, GDP and industrial output in western Europe grew by 72 percent, road traffic rose by 86 percent, while energy requirements rose by only 30 percent. This, together with changes in the energy mix and measures to control emissions, resulted in even slower growth in emissions of CO2 (15 percent) and NOx (13 percent) and a reduction in SO2 emissions of about 38 percent. These are significant steps in the right direction, but there is still immense scope for further improvements in energy conservation and efficiency.

Three events which acted as stimuli for the shaping of energy policies in recent decades were the oil price shocks of 1973 and 1979 and the Gulf crisis of 1990/91. To these may be may be added the UNCED Conference of June 1992. The main directions of policy have been improvement of emergency preparedness to mitigate the impact of sudden disruptions of supply, particularly of oil, increasing energy security, and reducing the environmental effects of energy production, transportation, transformation and consumption. The issues of principal concern to the FFI sector appear to be the diversification of energy supply and use, self-sufficiency, environmental protection and sustainable development, which are closely inter-linked.

Diversification has been pursued partly to reduce dependency on a few sources of total supply, notably the Middle East, for oil. It involves the development of alternative sources and is being achieved, inter alia, through selective taxation and subsidy measures and support for research and development (R&D). National strategies have varied according to individual circumstances, and progress achieved has likewise differed considerably. France, for example, developed a very active investment programme of nuclear power generation, which raised nuclear's share of TPES from 2.2 percent in 1973 to 37.1 percent in 1990. In Denmark, the share of “other” sources, including biomass (straw, woodchips, etc.), wind and solar, rose from 1.2 percent to 5.6 percent over the same period. Diversification is also intended to increase the share of “clean” or CO2-neutral fuels.

Efforts to raise energy self-sufficiency face problems of both the economic and environmental costs involved. Alternatives to fossil fuels are almost all more expensive than present oil prices (below $20 a barrel in 1993 and 1994) and/or are less convenient. Many of them are preferable from the environmental point of view, but one, nuclear power, raises serious issues of operational safety and the disposal of waste. Sweden has passed legislation for the phasing out of nuclear power generation, which accounted for 37 percent of its TPES in 1990, by the year 2010, but will seek to retain at least present levels of energy self-sufficiency through development of alternative sources, notably biomass, even though they might not be competitive without tax concessions, grants and subsidies. In Finland, peat supplies about 5 percent of TPES. It is considered to be a “slowly renewable” resource, but its commercial exploitation is becoming increasingly controversial for environmental reasons, and it may gradually be replaced by other domestic sources, notably wood which already holds a more important share of TPES (13 percent) than in other European countries.

Environmental issues related to energy production and use have taken centre-stage in all countries' energy policies. Good progress is being made, at least in western Europe, to reduce pollutants through the control of emissions (scrubbers, catalysers, etc.) and changes in the source mix, for example, replacement of coal and oil by natural gas, which is much “cleaner”, i.e. produces little SO2 and NOx. In some countries biomass is considered CO2-neutral, since it is renewable as part of the normal carbon cycle, but this fact is not yet universally recognised in legislation, for example, incineration of waste has not been allowed in Germany for environmental reasons, but this is now apparently under reconsideration. R & D and fiscal support continues to be directed to bio-energy, not only from wood, but increasingly from urban and agricultural waste. Where allowed, incineration of urban waste becomes increasingly attractive as other possibilities, such as landfill or recycling as industrial raw material, become over-supplied or saturated. Hydropower potential still exists in some countries, although many of the best locations have been exploited and new installations face growing opposition for environmental reasons.

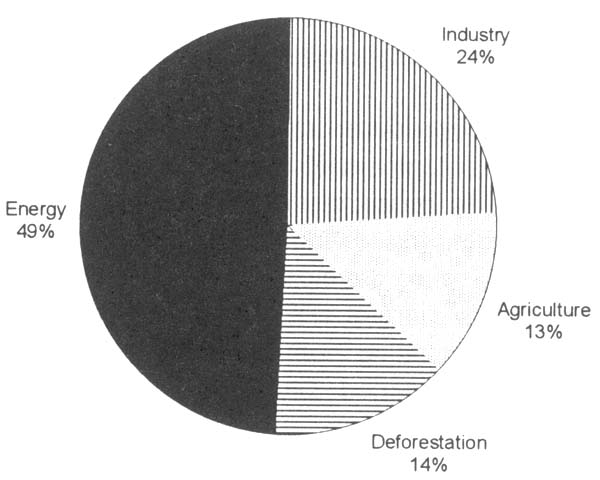

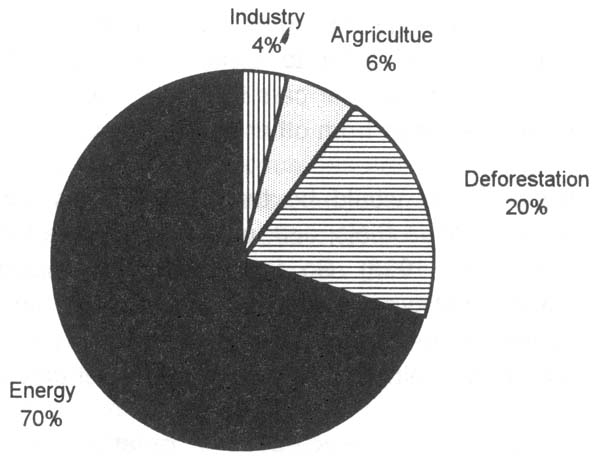

The political will of the world's governments to tackle the problem of climate change was enshrined in the Convention adopted at UNCED in Rio de Janeiro in June 1992 (UN, 1993a). The principal measure has to be the curtailment of emissions of CO2 and other gases of combustion, since this accounts for an estimated 49 percent of total emissions and 70 percent of those of CO2 (figures 6 and 7). Tropical deforestation is estimated to account for a further 14 percent of all greenhouse gases and 20 percent of CO2, and the halting and eventual reversal of this trend is also a high priority issue, not only for reasons of climate change (see Sections 2.4 and 2.8 on environment and trade respectively). Industry and agriculture between them account for the remaining 37 percent, but it should be noted that their contribution is much more in the form of gases other than CO2, notably CFCs (industry) and methane, CH4 (agriculture).

Figure 6: Contribution by sector of addition of “greenhouse” gases to the atmosphere

Source: OECD, The State of the Environment, 1991 (based on WRI data)

By far the largest share of fossil fuel consumption, and thus CO2 emissions, is still taken by the industrialised countries. With an increasing share of world population and expanding industrialisation and use of motorised transport, however, the consumption of fossil fuels will undoubtedly increase in absolute and relative terms in the developing regions.

Figure 7: Contribution by sector of addition of carbon dioxide to the atmosphere

Source: OECD, The State of the Environment, (based on WRI data)

In the very long term, a century or more, there seems to be little alternative - for reasons of climate change as well as environmental protection and sustainable development - to the phasing out and replacement of fossil fuels. While a marked shift to alternative fuels, even if actively encouraged, will not occur within the ETTS V timeframe (one to two decades), some steps may be taken in that direction: indeed, recent intergovernmental negotiations have been reconsidering, in the light of new information, the urgency of introducing measures to begin implementing the UNCED Convention on Climate Change. Steps to replace fossil fuels are likely to be brought on more for environmental and climate change reasons than by the threat of resource exhaustion. For a number of possible alternatives, technology already exists or should become available in the foreseeable future, such as for solar and hydrogen energy, but the costs are for the time being inhibiting. For others, such as fusion, there is no sign yet of a research breakthrough, even if the fundamental principles are understood. In the meantime policies are being directed towards (WMO/UNEP, 1988):

Development of existing alternative fuels, including solar, wind, wave, heatpump, and of course the various forms of bio-energy. Policy tools include government support for R&D and fiscal assistance for investment in and operation of the generating equipment.

Fundamental R&D on new sources of energy, such as fusion.

Development of technology for the cleaner and more efficient production and use of energy from fossil fuels. As already seen, significant reductions can be and have been achieved in reducing emissions of pollutants, even including CO2, per unit of energy output. The tools employed are the same as for 1. above. Several countries, notably the Scandinavian countries, Finland and the Netherlands, have introduced carbon or CO2 taxes, whose application at much wider levels, e.g. by the EC as a whole, is under consideration. All European countries have for many years taxed sales of petrol and diesel oil used by road vehicles, initially as a major means of revenue-generation by governments. But more recently, the possibilities of selective taxation of such products for environmental protection purposes have been receiving greater attention. Other measures, such as speed limits on roads, have been implemented for the same reason.

Improvement of energy conservation and efficiency in use. While the efficiency in the provision of final energy, i.e. the losses in converting primary supply to useable energy, is already quite high, that in the end-use of energy is low, even in the most efficient countries. There is a large theoretical potential for efficiency improvements, which would involve the introduction of many technological, organisational and regulatory changes or innovations, often involving trade-offs, such as cost of investment or operation, convenience, relative environmental impact, etc. If this is true of western Europe, it is even more so of the countries with economies in transition. For example: the potential for energy saving through changes in the design and construction of dwelling and other buildings in order to control ambient temperatures; and the potential for switching passenger traffic from private cars to public road or rail transport and for reversing the trend towards road freight transport from other forms (rail, water).

The effect of so-called “carbon taxes” would be three-fold: to discourage the use of fossil fuels; to encourage the development of alternative fuels; and, probably, to raise the price of energy in general, thus contributing to its conservation (IEA,1993). So far as biomass, including wood and waste paper, is concerned, it is necessary for the policy makers to take a position on whether it can be treated as a renewable resource and on whether its use as fuel is neutral so far as carbon emissions are concerned. The FFI sector is already convinced on this point, but its views are not yet universally shared.

National energy policies can hardly be developed in isolation, and international cooperation and coordination in the energy field has become more and more important. Apart from the UNCED Convention on Climate Change, other international initiatives in or within Europe have included the setting up of the International Energy Agency (IEA) within OECD, and a number of agreements, such as the European Energy Charter, signed in December 1991, which set a framework for east-west cooperation in the field of energy. Conventions drawn up under the aegis of the UN Economic Commission for Europe, which have particular relevance to energy policies, include the 1979 Convention of long-range transboundary air pollution and the 1991 Convention on international environment impact assessment. These will be considered further in the Section 2.4 on the environment.

Politics being the art of the possible, progress towards desirable policy objectives is usually far slower than needed. It often requires a crisis or shock, such as the oil price shocks, to mobilise public opinion and provide the basis for political decision-making. Just possibly, events such as UNCED may provide the stimulus for change instead of waiting for more traumatic crises to happen?

There are many important linkages between the energy and FFI sectors, notably because of: the environmental impact of energy activities on the forest; wood as a source of energy; demand for energy by the forest industries; and wood as an energy-conserving material.

Forest resources, forestry and wood supply

Two main aspects need to be considered under this heading: the role that the forests play as sources of

energy; and their role as carbon sinks. With regard to the first, it will be recalled that in the developing

regions as a whole, fuelwood accounts for some 80 percent of total roundwood removals. In the

industrialised countries, its volume and share dropped significantly over the long term until after the first

oil price shock, since when they partly recovered and subsequently levelled off. In Europe, fuelwood

removals of 58 million m3 in 1990 accounted for 16 percent of total removals. Energy remains the single

most important use of wood in volume terms, accounting for the equivalent of about 40 percent of

European removals, when account is taken of the energy use of wood residues, black pulping liquor and

waste paper as well as fuelwood. Greater use of fuelwood is inhibited by its inconvenience, compared

with “modern ” fuels, and price, rather than by availability.

Renewed interest in the potential of wood as a source of energy was spurred by the two oil price shocks of the early and late 1970s, but subsequently eased off again after each as oil prices fell. Various approaches to making wood for fuel more interesting have been considered: to reduce its harvesting cost by improved technology, for example by “green chipping” (chipping directly from the stump); to convert it to a more convenient form for handling and use - besides chips, there are other possibilities such as wood powder from which to produce briquettes, and conversion to gas; and to grow it in energy plantations with very high increment rates and short rotations. All these can give positive results under the right econom conditions, which would involve either general energy prices appreciably higher than they have been recent years or price support (subsidies, grants, etc.). Countries' interest in these possibilities differ according to their specific conditions with respect to, amongst other things, their perceptions of the future energy supply/demand balance, the extent and sufficiency of their forest resources, their overall energy self-sufficiency and access to other sources of supply and, for energy plantations, availability of suitable quality land.

Regarding forest resources, virtually all European countries are cutting less, often appreciably less, than their increment and have the physical potential to raise the volume of their annual fellings (UN-ECE/FAO 1992 and 1993). The bottleneck is mainly an economic one, but there are other factors involved (social environmental). Economic incentives could, therefore, be used to raise the production of fuelwood, if policies with this objective were strengthened or introduced (e.g. a carbon tax on fossil fuels), or if energy prices rose sufficiently.

There are strong silvicultural reasons for more active policies for the harvesting and use of wood for energy. In many countries there is a considerable backlog in thinning programmes; and many also have large reserves of low-quality and/or over-mature woodland that would benefit from clearance an restocking (if acceptable from the environmental and landscape point of view). One problem to be overcome is the often scattered nature of these resources, which either makes transport costs high or demands the establishment of fairly small, local wood-using plants. It has to be assumed that an substantial increase in fuelwood use would arise in industries or power-generation plants at the community or institution (e.g. hospitals) level, rather than in individual homes, although some farms might take more wood in biomass-using generators.

Energy plantations are relatively, but only relatively, land intensive, but require substantial inputs of fertilisers. Their advantages include their ability to produce a regular, homogeneous crop within a limited area. Whether wood is preferable from the economic or technical point of view to certain annual crop that could be used for energy will be discussed further in Section 2.6 on agriculture, which will also consider the likely availability of land for such purposes. Questions also arise about the desirability of energy plantations from the point of view of environmental protection and sustainability.

The use of forests as a carbon sink has also been carefully studied (IPCC, 1989; OECD, 1993). Climate change is a global problem requiring global solutions. Forests could contribute to slowing down an eventually halting the rise in atmospheric CO2 concentrations under two conditions: that they are net collectors of CO2 , which means their standing volume must be expanding and not, as with old-growth stands, be static or declining; and to have a measurable impact, new planting (afforestation) would have to be undertaken on a continuing and massive scale, probably in the order of hundreds of millions of hectares worldwide. The volume and area of Europe's forests have been expanding, and are expected to continue to do so, at a modest rate. To help serve the purpose of checking adverse changes in climate, the rates of forest expansion would have to be greatly accelerated. Given population densities an patterns of land use, it is doubtful whether Europe could make a significant contribution in this regard, but this will be considered again in the context of alternative uses of agricultural land (Section 2.6). As major producer of CO2, it could contribute much more effectively by reducing the rate of emission Nevertheless, climate change can still be used as a supporting argument, even if not a leading one, for policies to expand the region's forest resources.

Wood-processing industries

These are, for obvious reasons, the largest industrial users of wood and wood by-products for energy

The pulp and paper industries are energy-intensive, but the pulp industries in many countries have

developed their use of wood, bark and black liquors for energy to the extent that they are self-sufficient or

even net exporters of energy. Sawmills and wood-based panel plants are also extensive users of

internally-generated heat, steam and electric power, using bark and mill residues.

Some countries have provided incentives in the form of grants and subsidies to the wood-processing industries to increase the use of environmentally-benign and sustainable sources of fuels. This has generally meant investment in equipment that burns wood, either alone or in combination with other fuels. A few European countries have set up wood-using electricity generators and community heating plants, partly based on forest, industry and consumer residues. The extent to which these systems can be developed further will depend on such factors as the economic availability of such residues, which in turn depends on the volume of output of the primary products, such as sawnwood, the efficiency of production in terms of yield (and therefore the volume of by-product), the existence of alternative markets for the residues, e.g. for pulping or panels, and countries' legislation regarding the incineration of such wastes. The economics of using residues compared with alternative fuels is also a major consideration unless the former are being subsidised.

The wood-processing industries in a few European countries have progressed in the use of wood for energy to the point where it would be difficult to increase the volumes much more without bringing in fresh wood raw material expressly for that purpose. In the majority of countries, however, there appears to be still considerable scope for the greater use of residues for energy. Under what policy and economic conditions would this potential be realised? In the first place, the industries in the transition countries are backward in this respect, and it could be assumed that they will gradually catch up with those at least in west central Europe, if not those in the Nordic countries with their different resource and industry structure.

Everywhere, however, energy policies in support of sustainable development may through the use of legislation and incentives, push industries, including wood-processing, to take measures to reduce CO2 emissions. There is need for clarification where wood-burning stands in this respect. Is it justifiable to treat wood used for energy as benign on the argument that, as a renewable resource, it forms part of the natural carbon cycle, unlike fossil fuels? In this paper it is assumed that it is, in which case the wood-processing industries are well placed to respond to such policies. Indeed, under the right economic conditions, there could be greatly increased integration between the output of wood products, including pulp and paper, and energy generation with, eventually, the possibility of the latter becoming the principal product and the former by-products. That would involve, inter alia, full accessibility to national grids at fair prices of electricity generated by those industries. In some countries, there is still discrimination by the electricity companies against this practice by offering low prices or erecting other barriers.

International trade in forest products

Energy is a significant component in the cost of transport, whether by road, rail or water, and a very large

part of the energy used by transport is derived from fossil fuels. Should further energy price shocks occur

in the future, indirect impacts could be to raise the c.i.f. (or delivered) cost of imports compared to

domestically produced goods, as well as to increase the differential between f.o.b. and c.i.f. costs. The

effect of the latter would be felt more by low unit value goods, such as wood raw material, than by higher

valued goods, thus causing more of a shift in the assortment composition of internationally traded goods

towards the latter than might happen under unchanged conditions.

Assuming, however, a “business-as-usual” scenario for energy over the coming decades, involving no more than a continuation of past trends in improving energy intensity, it is difficult to envisage major changes in international trade patterns and composition of forest products attributable to energy policies. This also applies to the use of wood and its derivatives, such as wood gas, for transport. The technology is available and has been used, for example in road vehicles in parts of central Europe during the Second World War, and even today in a few parts of the world for railway steam engines, but under most present conditions it can be ruled out for reasons of convenience, cost and efficiency. Another major future energy shock could, however, change the picture.

Markets and demand for forest products

Energy-related issues could affect the demand for forest products in several ways. More extensive

policies to conserve the end-use of energy would increase the use of insulation materials, of which wood

is one of the best as a heat barrier, in dwellings and other buildings. Insulation standards are already high

in some countries, notably Scandinavia where wood remains the preferred structural material in single-family

houses. Other European countries will not approach Scandinavian levels of wood use, but could

show appreciable increases given appropriate incentives and application of building codes that are not

restrictive to the use of wood- as a supposed fire hazard, for example.

Studies have demonstrated that the in situ cost, in energy-using terms, of sawnwood and to a lesser extent wood-based panels is significantly lower than any of competing structural materials, such as brick, concrete, steel, aluminium, glass or plastics. This is partly because of the relatively low amount of energy needed to produce wood products, and makes a good case for preferring them when energy conservation is at issue. Measures to raise energy prices, e.g. through a carbon tax, would therefore help to improve the competitivity of wood in such uses as construction.

A further energy-related argument for the use of wood in construction, which may be given more weight in policy-making in the future, is that it stores carbon for a long period and thus contributes to the containment of the increase in atmospheric CO2. This argument is also relevant for other types of wood use involving the permanent or semi-permanent locking up of carbon, such as in books, some types of magazines and furniture, telegraph poles and sleepers. Wood use in construction, however, is more important than all these uses put together, and deserves careful attention by policy-makers.

Another increasingly important aspect is that wood and its derivatives, notably sawnwood and paper, are a major component of industrial and urban waste, which presents an increasingly difficult and urgent environmental problem. Ways to deal with these forms of waste are therefore considered in more detail in Section 2.4 on environment. Since the important link between energy and climate change is being covered in the present section, however, it may be recalled that burning of these wastes causes CO2 emissions which may be treated as part of the natural carbon cycle and as such therefore be acceptable to policy makers. In any case, burning may be preferable to landfill, which may lock up carbon for a longer period but does result in emissions of other noxious gases, such as CH4. Furthermore, use of waste for energy is at least contributing something to the economy, inter alia by reducing demand for landfill.