The agricultural and industrial revolutions over the past centuries in Europe, coupled with the population explosion since the 18th century, have had profound impacts on the environment, mainly for the worse as it became subjugated to other needs, notably the expansion of material wealth. Only when the potentially disastrous effects of a lack of respect for the environment on the well-being and even survival of the human race began to be generally recognised did a reaction set in, which might be described as the environmental revolution of the late 20th century (OECD, 1991; WCED, 1987). The accelerating pace of population growth worldwide, together with technological development, added urgency to the need to address the problems of environmental protection (UNEP, 1992). While policies specifically aimed at reversing the trend of environmental degradation began to appear several decades ago, we are still only at the early stages of the process of re-establishing equilibrium between human activities and the environment, which is at the core of what is nowadays termed “sustainable development” (UNESCO, 1992).

A basic cause of deterioration has been the emission of noxious and polluting substances by industry (including the wood-processing industries), transport, agriculture (including forestry) and households into the air and water and, either directly or via the air and water, into the ground. Admittedly, pollution is a problem that is within the reach of society to solve, and encouragement can be taken from the fact that active steps have been taken by many countries to reduce emissions. There is no room for complacency, however, and the pollution problem remains a serious one.

Another cause of environmental degradation has been the destruction of natural habitats through exploitation of natural resources or the need for land for agricultural, infrastructural and urban development. This has included the loss of wildlife habitats, decline in the number of plant and animal species, reduced landscape values and loss of biological diversity (UN-ECE, 1992b; WCED, 1987). The demand/supply situation with regard to the environment can shift over time. The nature of demand can alter as society changes, for example with rising standards of living, and that of supply also as resources become exploited. A typical example is that of old growth or natural forest: people's perceptions of the need to preserve it change with increasing scarcity.

Pollutants are emitted into the air in the form of gases and particulates resulting from the burning of fuels, the industrial processing of minerals and other raw materials as well as other sources such as animal husbandry. The list of pollutants is long, but among the most important are SO2, NOx, O3, VOCs (volatile organic compounds including those such as CFCs destroying the stratospheric ozone layer) and heavy metals. CO2 may also be considered a pollutant. The deposition of pollutants in wet (“acid rain”) or dry form has resulted in damage to buildings and monuments, fresh water systems and to terrestrial fauna and flora, notably to forests. Human health has also been affected in badly polluted areas or close to heavily polluting sources.

Pollution of rivers, lakes and groundwater has attracted particular attention because of its effect on water used by people, especially drinking water, but the discharge of raw sewage and industrial effluents directly into the sea has also been a cause of increasing concern for human health as well as fish and other marine life (UN-ECE, 1992b). This has been particularly serious for partly or wholly enclosed seas such as the Mediterranean, Black and Baltic Seas, and even the North Sea. These have been degraded, not only by direct discharges but also by effluents brought down into them by rivers as well as their illegal use as dumping grounds for dangerous chemicals and nuclear waste and from oil spillages.

Many industries have contributed to water pollution, among them the pulp and paper and to a lesser extent other wood-processing industries. The most noxious water pollutants, however, have come from the chemical- and metal-producing and using industries. As a result of increasingly severe legislation, many countries have made considerable progress in reducing the volumes of effluents, and the water quality in some rivers and lakes has improved to a noticeable extent. The process of recovery is, however, lengthy and costly and can be delayed by accidents.

The problems of water pollution by agriculture and horticulture have increased with the trend towards intensification of farming operations (FAO, 1988; FAO, 1990). Part of the problem has arisen from the heavy application of fertilisers and pesticides on arable land, with consequent leaching of chemicals into the groundwater and eventually into water supplies. Nitrogen in water supplies for domestic use has been a particular concern, as has the eutrophication of lakes. The use of certain pesticides, especially those which are long-lasting such as DDT or have a broad-spectrum effect, e.g. non-selective insecticides, has been found to have deleterious effects on fauna and the natural food chain, and possibly also on humans, for example some chemicals are said to have caused miscarriages or birth defects. The use of pesticides has become increasingly tightly controlled, but as in industry, there are costs to be paid because of the use of less intensive farming methods, greater losses and lower yields. This is also discussed in Section 2.6 on agriculture. The raising of large numbers of farm animals in a limited area has also created some major problems of liquid and solid waste disposal, and even air pollution.

With the increasing concentration of populations and industry in urban areas, the problem of solid and liquid waste has grown to very serious proportions in the industrialised countries and others with large conurbations, such as Mexico City, Cairo and Bangkok. Municipalities have had difficulties in extending sewage systems to cope with the volumes discharged daily. A sizeable proportion of the urban populations, mostly in southern Europe, are still not provided with any sewage disposal system, with discharges often going directly into rivers and the Mediterranean, Baltic and Black Seas. Increasingly strict EC regulations on water quality are being supported by financial assistance for the necessary improvements to water supply and sewage systems.

Solid waste has been becoming an increasing problem in many countries, notably those such as Germany and the Netherlands where landfill sites are becoming used up and new ones are difficult to open up, for political and environmental reasons (Anon., 1993). The export of such waste has been becoming less and less acceptable. Consequently, much attention is being given to ways and means of, in the first place, reducing the generation of solid waste, and secondly, of recovering and recycling as much of it as possible (CEC, 1975; 1990a and 1991a).

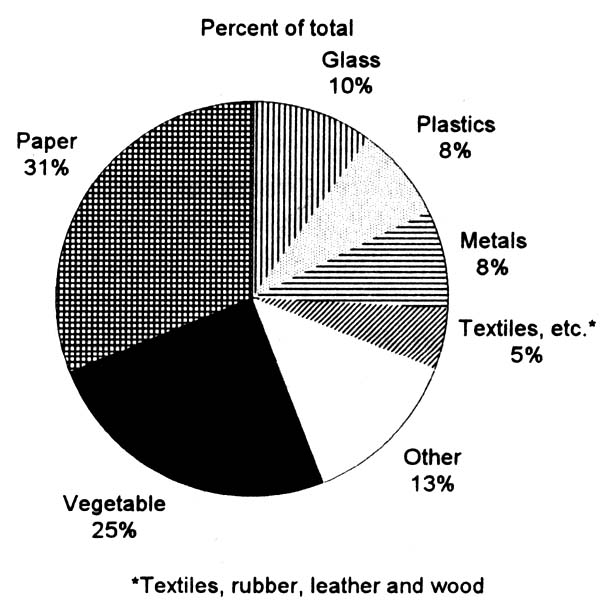

Both the volume and composition of municipal waste change with rising standards of living. Volume has expanded somewhat more slowly than economic growth: in the OECD countries, for example, municipal waste generated per head rose by about 1.5 percent a year between 1980 and 1990, compared with a per caput GDP increase of over 2 percent. The most striking change in composition that comes with rising standards of living is the greater share of paper. In low income countries this accounts for 2 percent of the total, while in industrialised countries the share is 31 percent (figure 8). Another type of solid waste, which apparently is not included in the municipal waste statistics, is rubble and other forms of debris from the demolition of buildings. Its volume in Germany is five times that of municipal waste; most of it finishes up in landfills and is not recycled.

The urgency with which environmental issues have been addressed has varied enormously from country to country, depending to a considerable extent on the ability of environmental movements to generate public and political support for change. One group that has lagged behind in this regard has been the countries of eastern Europe while they were still governed by one-party systems (Boyd, 1993; Knoepfel, 1993; UN-ECE/UNEP, 1993). Although the previous regimes had enacted a considerable amount of environmental legislation and signed many of the international conventions, their compliance was generally poor because of lax enforcement. The environment was largely sacrificed in the push for material development. However, increasing public disgust with the deterioration of the environment was one of the factors leading to the revolutions of 1989/90 and the start of the process of transition towards a pluralistic society and form of market economy. Now, the transition countries are faced with a huge task of cleaning up the environment, with immense costs involved which are quite beyond them to cope with alone. Furthermore, despite the recognition of the urgency of tackling these issues, the new regimes have first had to address other even more urgent problems, such as putting their economies onto a stable footing and providing the population with an acceptable living standard.

Figure 8: Composition of solid waste in industrialised countries

Source: The Economist, 29 May 1993 (from Environmental Resources Ltd.)

This general description of man-caused stresses on the environment would not be complete without mention of nuclear fallout from a number of accidents, of which the Chernobyl disaster - partly a consequence of a State-controlled political system, - has been the most serious, the depletion of the ozone layer caused by CFCs, and noise pollution.

It is difficult to pinpoint where and when the global movement for environmental protection originated. There were, however, a number of pathfinding opinion-formers in the 1960s, such as Rachel Carson, who in “The Silent Spring”, successfully alerted public opinion to the dangers and aroused a remarkable response. Today there are many non-governmental organisations (NGOs) concerned with the environment. In the early days of environmental consciousness, the political dialogue was mainly between the legislators and the polluters (industry, etc.), but it has become more and more a three-way process involving also the public, usually represented by NGOs. “Green” political movements have grown up in many countries with representatives in parliament. At the same time, existing political parties have embraced the environment as a major component of their platforms.

Extensive legislation has been introduced in all countries to deal with numerous aspects of the environmental problem. Almost from the start, however, countries recognised the international dimension of environmental protection, and from the first major international conference on the environment, the 1972 United Nations Conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm, international co-operation has been significant (UN, 1993a). Over the past two decades, more than a hundred international agreements and instruments dealing with environmental matters of concern to Europe have been established.

To illustrate the scope of this collaborative work, conventions adopted under the aegis of just one body, the UN Economic Commission for Europe, may be cited (UN-ECE, 1992e):

Convention on Long-range Transboundary Air Pollution, 1979. This has been ratified by 32 Governments and the European Community5, and was the first international legally binding instrument to deal with problems of air pollution on a broad multilateral basis. So far, four protocols have been added to the convention:

Convention on Environmental Impact Assessment in a Transboundary Context, 1991. This has been signed by 28 countries and the EC, and was the first multilateral treaty to specify the procedural rights and duties of States with regard to the transboundary impact of their activities.

Convention on the Transboundary Effects of Industrial Accidents, 1992. This has been signed by 23 countries and the EC. It is intended to promote inter-governmental co-operation for the prevention of, preparedness for, and response to the effects of industrial accidents.

Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes, 1992. This has been signed by 22 countries and the EC, and is intended to strengthen national and international actions aimed at protection and ecologically sound management of transboundary waters, both surface and groundwaters.

These conventions and their protocols provide the nucleus of a environmental legal framework for the countries of the region. Up-datings will occur as progress is made in dealing with the problems addressed and as new information becomes available. For example, further protocols to the Convention on Long-range Transboundary Air Pollution are envisaged based on the concepts of critical load and cost effectiveness.

Although global in scope, the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil in June 1992, including the lengthy processes of negotiation which led up to it, offers another example of international co-operation at both the world and regional levels on environmental matters (UN-ECE, 1993f). The major outcome of the Conference consisted of five negotiated and agreed documents and conventions:

the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development;

the Framework Convention on Biodiversity;

the Framework Convention on Climate Change;

the non-legally binding authoritative statement of principles for a global consensus on the management, conservation and sustainable development of all types of forests;

Agenda 21.

There was also a recommendation to the United Nations General Assembly to initiate negotiations on an International Convention to Combat Desertification. Altogether, these documents provide a massive amount of useful material, the difficulty being their indigestibility - the “concise guide” to Agenda 21 is over 200 pages long (UN, 1993a). The statement of principles on forests consists of 15 sections, virtually all of which have relevance to the present study.

A considerable volume of legislation on environmental matters has been established by the European Communities, which its twelve member countries are legally obliged to observe (CEC, 1990). Much of the legislation deals primarily with specific sectors, such as agriculture, industry, construction, transport and so on, but has an environmental protection purpose or element. Examples of the type of legislation are the Directives on the recycling of waste (CEC, 1975, 1990a, 1991a and 1993a).

It is not possible to give details here of national environmental policies. There are certain common features, however, which can be summarised as follows:

The “polluter pays” principle. This assumes that the source of pollution can be identified. Depending on the instrument used to apply the principle, it generally means that any additional costs are eventually passed on to the consumer. The principle may be eased in certain circumstances by government support for anti-pollution measures, but this again puts the burden on the public, in this case the tax-payer;

Reduced consumption of resources. Apart from directly pressure on the natural resources being exploited by man, more efficient use of resources automatically results in reduced output of pollutants and waste. This is particularly important in the use of non-renewable natural resources, such as fossil fuels and minerals. It also implies that preference should be given to the use of renewable and environmentally benign resources. It is questionable whether anything like the full potential of protecting the environment has yet been recognised in resource conservation policies, witness for example, the slow pace of the switch away from fossil fuels. There are, of course, good economic arguments for maintaining the status quo for as long as possible, but these arguments probably do not take fully into account the environmental and social costs and the long-term perspective, i.e. sustainability.

Intensity of resource use. The objective is to reduce the quantity of resource input per unit of output of product, energy, service, etc. This involves the application of appropriate technology to raise efficiency which also results in the reduction of harmful emissions as a secondary effect.

Preservation or conservation of the environment. The distinction must be made between “preservation”, which implies maintaining the present status quo, and “conservation”, which recognises that the natural environment is in a state of equilibrium, and that it may be utilised by man in many ways without damaging it, provided its use is carefully managed. This is at the heart of the discussion on the use of renewable resources, such as forests. Even with non-renewable resources, their exploitation can be compensated by measures to ensure that they are replacable by something else in the long run, for example fossil fuels by solar energy. Nevertheless, the argument should not be whether there should be preservation or conservation. Preservation of a certain proportion of the numerous different types of natural resource is essential for reasons of bio-diversity. The problem faced by policy-makers is, firstly, to decide what proportion it is necessary to preserve, and secondly, how. Nowhere is this dilemma more acutely experienced than in the tropical rainforests.

An integrated approach to environmental policy-making. This has two aspects: the more general one is the integration of environmental policies with those of related sectors, such as land use, agriculture, urban development, industry and so on (UN-ECE, 1992f). Policy-makers and planners increasingly recognise the necessity to take full account, right at the start of the development process, of the environmental impact of their actions. This is seen in the greater use being made at the local, national and international levels of environmental impact assessments.

A serious political problem that quite often arises is to determine which part of a Government is to have administrative responsibility for an integrated policy. A typical example concerns rural development. Several ministries may claim to have primary political responsibility for this, notably the ministries of agriculture and of the environment. Which one should play the lead role? A second aspect of an integrated approach is more specific: pollution should be treated as a multi-medium, multi-pollutant problem, whereas in the past the tendency has been to tackle different types of pollution separately. In fact reducing one type of pollution may well cause an increase of another: remove pollutants from water effluent and they may become solid waste. An integrated approach is therefore necessary to find the optimal solution. This is being increasingly recognised in policy-making. Thus in 1991 the OECD Council of Ministers agreed a Recommendation on the principle of applying an integrated concept in their pollution prevention and control policies, and on a framework for such policies (OECD, 1991); and the European Community has put forward proposals for an Integrated Pollution Control Framework Directive. These moves reflect measures being taken at the national level.

The “five Rs” principle. The five Rs are reduction, replacement, recovery, recycling and reutilisation, and the principle refers to industrial products, residues or wastes, although in practice it also covers the commercial and domestic sectors (UN-ECE, 1992j). A Recommendation to UN-ECE Governments on this principle was adopted by the 5th session of the Senior Advisers on Environmental and Water Problems in 1992. It seeks to move waste management policies away from reactive remedies towards anticipatory and preventive action.

Crucial to the success of policies are the instruments by which they are implemented; these fall into two main categories, regulatory and economic (McClone, 1993; UN-ECE, 1993a). Without attempting to be exhaustive, the following is an indicative list of instruments, which may be used in support of environmental policies:

Developing “fair” as well as effective environmental policies becomes particularly sensitive when they have an international dimension. As seen in the negotiations of the GATT Uruguay Round, environmental protection measures may be seen as intentional or unintentional non-tariff barriers to trade.

Forest resources, forestry and wood supply

Forest ecosystems are a major integral part of the global ecosystem. It was surprising, therefore, that

they received so little attention at the 1972 Stockholm Conference on the Human Environment, but this

lack was more than made good at UNCED in Rio in 1992 (Barthod, 1993). Some of the main interactions

between forests and the environment are considered below, with the main emphasis being put on

actual or potential impacts on wood supply.

In temperate regions, and particularly in central Europe, the link between air pollution, acid deposition and forest decline (“Waldsterben”) has received close attention over the past decade. The Executive Body for the Convention on Long-range Transboundary Air Pollution set up a co-operative programme to monitor forest damage on an annual basis. Visual monitoring is carried out on a representative sample of coniferous and broadleaved trees on a virtually continent-wide basis, whereby the extent of foliage loss and discolouration is assessed, the assumption being that this is attributable, at least partly, to the effects of wet or dry deposition of pollutants on the foliage or on the soil (UN-ECE, 1993b).

The observed extent of the forest decline, which affected to some 7 million hectares in Europe (of which 250 000 hectares of dead of dying stands, most of the latter being along the borders of the former Czechoslovakia, Germany and Poland - the ‘Black Triangle’), was one of the main factors leading countries to adopt legislation to reduce emissions of SO2 and NOx. Research has not yet been able to establish a clear link between cause and effect of forest decline, however, and there has been a growing consensus that air pollution is only one of a combination of causes, and not necessarily the main one, of the decline. Other attributable factors include climate patterns, notably prolonged drought and frost, topography, and certain silvicultural practices such as the planting of species outside their natural range. Doubts have also arisen about the reliability of defoliation as an indicator of a tree's vitality: for some species it appears that a 25 percent needle or leaf loss can occur without noticeable effect on health and productivity. Furthermore, in some areas with relatively light deposition, pollutants actually seem to act as a fertiliser and to stimulate growth, at least for a time.

Thus the debate on air pollution damage to forests seems to have entered a new phase, where attention is being directed more to the combination of factors that affect their health and vitality, among which air pollution is one. However, where whole stands have died and have been difficult or impossible to regenerate, the principal cause has usually been readily apparent, namely massive deposition from local point sources that have been using sulphur-rich fossil fuels, especially brown coal, or emitting heavy metals or noxious chemicals.

Analyses, for example by IIASA, have been carried out on the impact of air pollution on the FFI sector, but some of the assumptions used and conclusions reached may now be in need of reappraisal (Schlaepfer, 1993; UN-ECE, 1993b). Forest decline is undoubtedly a serious problem and deserves to be closely monitored and tackled by appropriate policies, but new approaches are needed in order to determine the cause-effect relationships and the extent and nature of damage actually occurring to the forest ecosystem. Its impact on long-term wood supply is difficult to assess, but some evidence of a slowing down of increment rates and the introduction of a number of measures, for example moves to diversify the composition of coniferous stands by the introduction of more broadleaved species, may lead to some reduction of increment and long-term wood supply. In the shorter term, however, sanitation fellings could increase availability.

Fire has been an element of many natural forest ecosystems, including some in Europe. It has also been used by man since time immemorial as a management tool in agriculture and forestry, but in more recent times it has come to be regarded as an environmental threat, especially in areas with fragile forest ecosystems such as around the Mediterranean basin. In Europe, forest fires are mostly caused by man through negligence or by arson and are thus, like air pollution, something that man himself has the possibility to prevent and control. The importance of the forest fire issue has been highlighted at such major conferences as UNCED and the Ministerial Conferences for the Protection of Forest in Europe.

Until relatively recently, most questions about nature conservation and bio-diversity were focused on tropical forest ecosystems (FAO, 1990c). These matters have now attracted considerable notice also in temperate and boreal forests. Pressures have greatly increased to preserve or at the very least to conserve the remaining areas of natural forest in Europe, most of which are located in the Nordic countries (Dudley, 1992). Elsewhere there are small scattered areas of woodland, which may be described as natural or at least semi-natural. One argument is that these contain potentially priceless genetic reserves and are more biologically diverse than the vast majority of European forests that have been used, managed and altered by man over many centuries. Plantations, especially monocultures of exotic species, are considered to be genetically impoverished and ill-equipped to serve the variety of functions that modern society requires. Such stands are also felt to provide poor habitat for wildlife or at best to support a range of birds and animals different from the “natural” range.

However justified they may be, these arguments raise a number of questions which revolve around the basic problem of finding an acceptable balance. If natural forests are to be preserved, how many of them and where? Who should be responsible for the cost of preserving them, especially when they are privately owned? How far should silvicultural practices be adapted to diversify the managed forest, which inevitably implies a compromise between its economic role and the environmental and social functions? Behind this dilemma lies the fact that the information needed for such policy decisions is still far from adequate: most forest resource inventories provide good data on which to base management for wood production, but not much more.

Therefore it can be stated that European countries' policies will continue to evolve with the objective of preserving at least part of their remaining natural and semi-natural forests and of promoting nature conservation.

As to the sustainability of forest management in Europe, a distinction needs to be made between sustainable yield (normally meaning yield of wood) and the sustainability of the forest ecosystem (FAO, 1992l). Most countries in the region can reasonably claim that their forest management results in at least a sustainable if not expanding yield of wood. The question is whether this is being achieved at the expense of biological diversity, and/or with the input of environmentally harmful chemicals, and/or by giving scant attention to the non-wood functions of the forest. The answer in many cases appears to be that, under this broad concept of sustainability, European forestry could be made more sustainable than it is today, by adapting management systems to follow more closely along “natural” lines and to fully respect bio-diversity. In fact, many countries' policies are already moving in that direction. UNCED helped to arouse still greater interest worldwide amongst policy-makers and managers in ways to reconcile sustainable yield with sustainable forestry in the broad sense. It actually reflects thinking that has been gaining ground in recent years, which is brought together in the “Pro Sylva Europe” movement, which has been receiving support in some academic and research circles as well as among silviculturalists. This seeks to encourage forms of silviculture that offer a holistic approach through the marriage of economic and environmental objectives.

The impact on wood supply of such changes in policy emphasis would be gradual, but in many instances would be towards a reduction in the volume of wood production, or at least in modifications to supply. Where production was reduced, this might be compensated by a larger proportion of higher value wood, for example from the growing of more broadleaved species on longer rotations.

Some impact of stronger waste management policies has already been felt by forestry, and this is likely to intensify. The share of recycled waste paper in paper furnish has risen considerably over recent decades and, with many countries bringing in legislation specifying the proportion of waste paper to be used in various assortments of paper and paperboard, the share will increase further at the expense of virgin fibre. The latter comes either from small-sized roundwood, mostly thinnings and tops, or from sawmill residues. The loss of markets for thinnings has serious consequences for the whole cycle of silviculture and the economics of forest production. The thinning regime of a stand determines the age at which the final crop reaches maturity (usually sawlog size) and also its quality. Lack of or delay in thinning may raise the risk of damage from fire, or storms or snow-break. The suggestion to impose a tax on primary raw materials in order to encourage recycling, which a few countries are considering, would thus be counter-productive if applied to wood. This underlines the need, mentioned earlier, of an integrated approach to environmental policy-making, which views the whole cycle of the raw material resource.

Wood-processing industries

The past record of the forest industries, especially pulp and paper mills, as polluters was not always

good, but in most European countries they have gone a long way towards eliminating the emission of

both air and water pollutants in response to public opinion and legislation. The technology is available,

but is easier and less expensive to install in new mills than in existing ones. Almost total elimination of

emissions can be achieved with closed circuit systems, but these can often not be used, partly for

reasons of cost, and even where they are, they cannot stop the emission of CO2 from fuel burning.

Modern pulpmill technology allows the recovery and re-use of the chemicals used in the process as well

as the ligneous waste matter (lignin, fibres), which can be used for energy. Of the wood-based panels

industries, fibreboard (wet process) faces similar environmental problems as pulping, with the added

difficulty that the scale is usually much smaller and consequently the solutions are more expensive per

unit of output to apply. Particle board and dry process fibreboard mills have to control emission of

particulates (dust), and all these industries may have problems with the disposal of contaminants

(glues, chemical preservatives against fire, insects or fungi, surface coatings, etc.). Sawmills may also

have some of the same problems, but are comparatively “clean” from the environmental point of view,

although some problems have arisen with wood impregnated with preservatives or other chemicals or

that have been glued or painted. Another favourable factor is the low energy input/sawnwood output

ratio.

The particular difficulties, that are faced by the countries with economies in transition in coping with environmental protection, apply to their wood-processing industries. Privatisation may make the enforcing of environmental legislation even more difficult to apply. Since the events of 1989/90 many of the wood industries, like the whole of the industrial sector in these countries, have suffered steep falls in output and some have had to be closed down. In the course of the recovery that will occur in the coming years, output of forest products will expand, partly as the result of investment in completely new mills, which are likely to incorporate the required technology for environmental protection. The transition countries can expect assistance in this from the financing institutions, such as the World Bank and EBRD as well as western partners in joint ventures, whose policies now fully encompass the principles of environmental protection.

International trade in forest products

It is proposed to treat the impact of environmental policies on trade in Section 2.8 on trade. One of the

most crucial aspects to consider there will be the consequences for European imports of deforestation in

the tropics and environmental pressures there and in other areas with natural or old-growth stands. That

discussion will also cover the questions of supply from overseas sustainable sources, eco-labelling and

the use or misuse of environmental legislation for the protection of domestic industries and employment.

Markets and demand for forest products

Public concern for the environment often preceded that of the legislators, and has proved to be enduring,

even when more immediate concerns, such as unemployment, have intervened. The public has

generally been willing to accept legislation aimed at ensuring the efficient and unwasteful use of

materials, including wood products. Environmental NGOs have played an important role, which has

usually been constructive in shaping public opinion.

Two of the main issues have been the impact of consumption of certain forest products on the environmental protection and sustainability of their source; and waste and recycling. With regard to the first, attention was initially directed to the problem of tropical deforestation and the role that the importation and use of tropical hardwoods had in it. Building codes and municipal laws in some countries now restrict or ban the use of these species for certain uses, and some industries and retailers have stopped producing and selling furniture and other goods that cannot be shown to use wood from a sustainably managed source. The volume of tropical hardwood being imported and used in Europe has been declining in recent years, but it is difficult to assess the extent to which this has been due to these measures or to other factors, such as reduced availability for export in the producer countries, the general slowdown in the economy and especially in construction, or changes in fashion and technology.

The European buying public has also been made increasingly aware of the environmental protection issues in certain temperate forests, notably in the Pacific Northwest of the USA and Canada and more recently also in old-growth forests in parts of Scandinavia, but again it is difficult to tell what impact, if any, this has had on buying behaviour. Probably there is a willingness among many people to adapt their buying in the cause of environmental protection, and perhaps even to pay a premium where environmental costs are shown to be included in the price of an article. For the most part, however, they are prepared to have decisions taken for them through legislation, assuming it is based on sound information: unfortunately this has not always been the case. For example, use of wood from sustainably managed forests assumes that the definition of “sustainably managed” is clear, which it is not; and that there exists proper control of management practices and the sources of the wood, which there does not in all cases.

The public in many countries has also embraced the principle, if not always the spirit, of waste management (OECD, 1992). Newspapers, other printing and writing papers and other types of paper and paperboard produced wholly or partly from recycled paper, are fully accepted. There is also willingness to separate in the home recyclable paper from other rubbish. Indeed, the ability to recover waste paper has sometimes surpassed the possibilities to make use of it, as was seen in Germany, where the recent far-reaching legislation on recycling of packaging and other types of paper resulted in serious problems because of the insufficiency of suitable processing capacity (OECD, 1993).

Legislation being introduced in many countries is likely to lead to efforts to reduce the volume of goods being put on sale to the public, so as to ease the problem of waste disposal. A particular target is packaging which, after construction, is the most important end-use of forest products in volume terms [perhaps roughly equal to furniture] (Anon., 1993a). Packaging is also an area where forest products face intense competition from other materials, notably plastics and glass, some of which are less environmentally benign. Certainly some plastics have more recycling problems and costs than other materials. Nevertheless, growth in demand for wood used in paper and paperboard packaging may slow down or even decline over the medium- to long term in response to resource conservation and waste management policies.

Finally, mention should be made of the environmental issues relating to the production and use of some wood products, or rather to problems that may spring from their combination with certain products, such as glues, preservatives, plastic or metal foils and surfacing materials. Considerable progress has been made in ensuring that these products are environmentally benign or can be satisfactorily recycled, but “contaminated” wood products can be problematic in recycling, and this may have an influence on buyers' decisions.

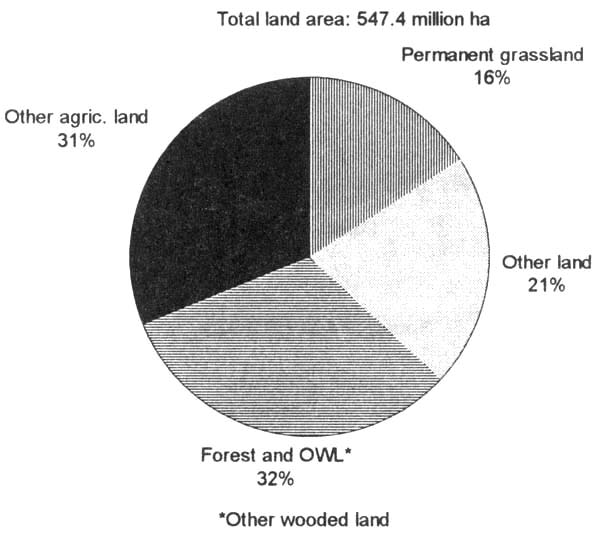

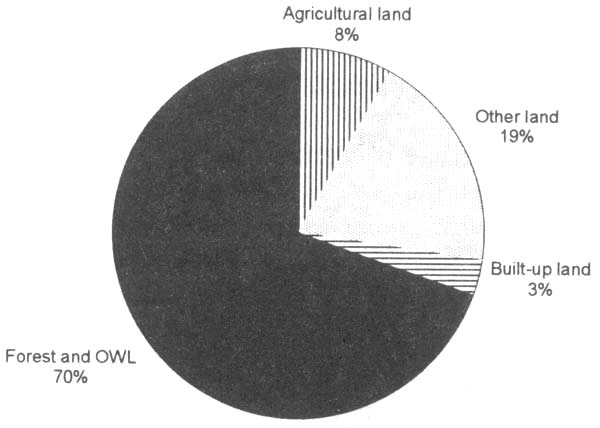

Before looking at agriculture in the next section, the more general issue of policies affecting land use and rural and regional development is considered here, since both the agricultural and FFI sectors are an integral part of this far broader issue. Land may be sub-divided into three main categories: agricultural land; forest and other wooded land; and other. As seen in figure 9, agriculture accounts for nearly half of the total European land area (excluding inland waters), forest and other wooded land for nearly one third, and all other types of land use for the remaining one fifth (FAO, 1992a).

Figure 9: Main land uses in Europe (total)

Source: FAO, ERC/92/4

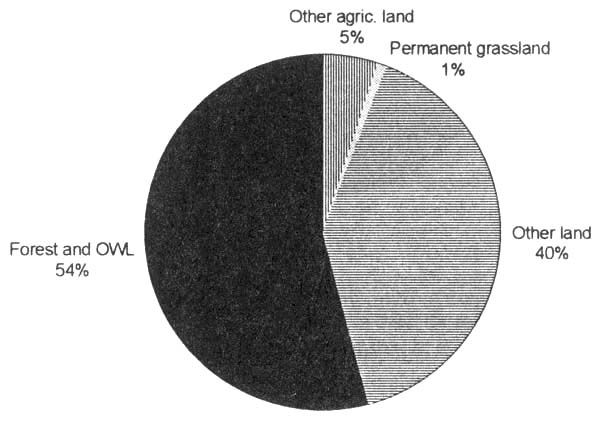

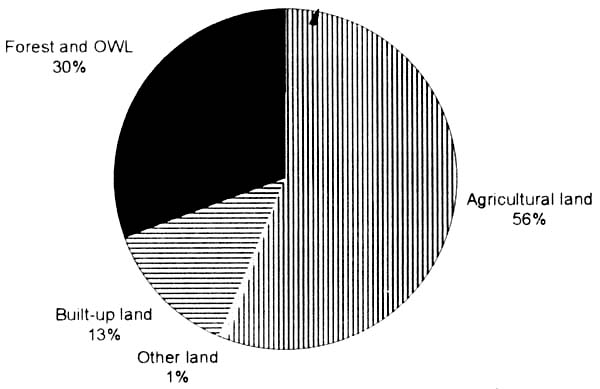

Figure 10: Main land uses in Northern Europe (Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden)

Source: FAO, ERC/92/4

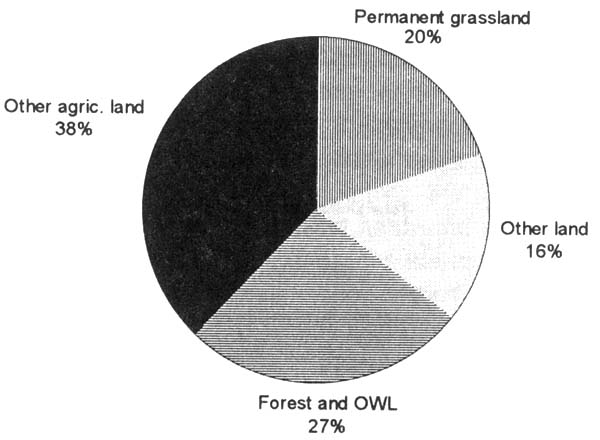

There are wide variations in the pattern of land use between European countries, but the most marked at the sub-regional level is between the four countries of northern Europe (figure 10) and the rest of Europe (figure 11). In Northern Europe, forest and other wooded land (FOWL) predominates with well over half the total, while other land use categories account for two fifths, and agriculture only for 7 percent. In the rest of Europe on average, agricultural land is by far the most important category with nearly three fifths of the total area, followed by FOWL with over one quarter, and all other categories with 16 percent. The difference between the two sub-regions is mainly accounted for by climatic factors that are unfavourable to agriculture in the Nordic countries.

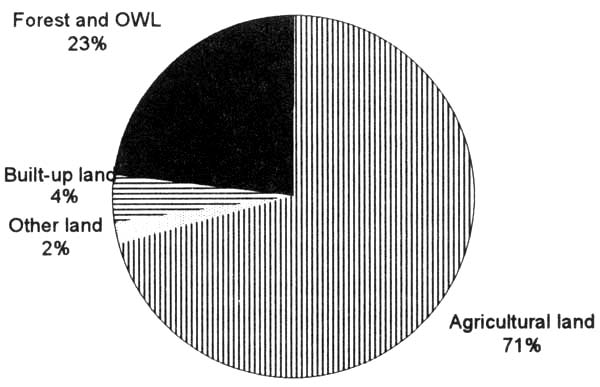

Figure 11: Main land uses in Europe other than Northern Europe

source: FAO, ERC/92/4

Figure 12: Main land uses in Sweden, 1983–1985

source : UN-ECE, SSS No 39, 1987

“Other land” comprises two totally different categories. On the one hand, there is “built-up land”, which includes human settlements and their ancillaries, such as industrial and commercial sites, roads, railways, and land used for other infrastructural and communication purposes. On the other hand, there is bare land, such as mountains above the tree line and land which might once have been classed as “Wasteland”, but is more and more valued for environmental or social reasons, such as wetlands, treeless heathland, tundra, etc. Not all countries have land use statistics which adequately differentiate between the various categories of “other land”, but there are very marked differences, as may be seen from figures 12, 13 and 14 for Sweden, the former Federal Republic of Germany and Greece, respectively (UN-ECE, 1987). In Sweden, most of the “other land” is not built on (19 percent of the land total) and only 3 percent is built-up land. In Germany, with its highly developed industrial base and dense population, the proportions are reversed - 1 and 13 percent respectively. Greece falls between the two, but still has twice as much built-up land as other categories.

Figure 13: Main land uses in former Federal Republic of Germany, 1985

Source: UN-ECE, SSS No 39, 1987

Figure 14: Main land uses in Greece, 1981

Source: UN-ECE, SSS No 39, 1987

Over the past thousand years or so, major changes have taken place in the land use pattern of nearly all European countries, which were largely covered with forest before settled farming spread across the continent. Forests gave way to agriculture and were cut down also to provide fuelwood and material for construction, ship-building and certain types of industry, such as glass-making, which required large volumes of fuelwood. Their area reached a low point sometime early in the 19th century, since when there has been a partial recovery. The area of agricultural land has been pushed in two directions: further expansion in some areas through conversion of forest or other land; and losses in other areas, particularly around towns and cities, to use as building land, for roads and so on. In recent decades, the latter trend has been the stronger, and has also been accompanied by afforestation, both natural regeneration of abandoned farmland and plantations. Figure 15 shows the changes between 1973 and 1988: a net decrease of over 9 million ha in agricultural land was offset by net increases of 3.7 million in FOWL and 5.5 million in “other” land. While most of the latter was probably in the “built-up” category, there may also have been areas of abandoned farmland becoming wasteland, e.g. as a result of desertification in areas of southern Europe or of depopulation in remote, hilly regions. Unfortunately, the data are not available for all countries with which to construct a matrix of the changes for Europe as a whole, so that it is not possible to observe the pattern of land use change at the regional level.

Figure 15: Changes in land use in Europe, 1973 to 1988 (million ha)

Source: FAO, ERC/92/4

The use to which land is put may change without entailing a change in its nature. Rural areas may be designated as National Parks which may alter but not necessarily reduce the agricultural and forestry activities, while extending other uses such as tourism and recreation and curtailing exploitive activities, such as quarrying or mining. Other areas may become nature reserves, which largely exclude previous uses in favour of a single use such as nature conservation and wilderness areas, but do not alter the look of the area; indeed, the change is made precisely because of the nature of the site. Changes in land use between rural activities, e.g. between agriculture and forestry, are reversible. Those from rural to urban use are irreversible, except on a very long time scale and could only occur if social conditions changed to an extent that is unimaginable today. Some of the most difficult policy and planning decisions therefore concern changes to the rural-urban interface.

In most parts of the world land is having to be shared amongst increasing human populations. Therefore, as underlined in UNCED Agenda 21, an integrated approach to the planning and management of land resources is essential. Agenda 21 calls for governments, in collaboration with appropriate local, national and international institutions and groups, to give immediate priority to promoting the most efficient use of land and its resources, and create mechanisms to facilitate active involvement by all parties concerned in decision-making. Goals should be set and policies formulated to address the environmental, social and economic factors involved in land resource use.

Already before UNCED, increasing attention was being given to the need for more intensive management of the land and its resources at the regional and local level to achieve and maintain reasonable balances between population, economic development and social welfare, while at the same time meeting ecological standards (OECD, 1993i). The UNCED outcome will serve to accentuate the need for regional planning and management along these lines.

Policy measures include proactive land use planning and land capability assessment, and legislation or regulatory controls on changes in land use. In practice, numerous conflicting objectives have to be reconciled in order to achieve the most rational use of land, and these objectives, or the priorities attached to them, will change over time. Without being exhaustive, the following are some of the main objectives, as seen from a European perspective:

The complexity of the problems involved demands an integrated approach, as prescribed in Agenda 21. This requires not only the involvement of the public but coordination between the numerous agencies and institutions concerned with or responsible for different sectors of rural and regional development. This is often far from easy to achieve.

Forest resources, forestry and wood supply

Forest and other wooded land has an increasingly important role in providing “non-wood benefits”, both

material (food, cork, resin, Christmas trees, etc.), environmental (nature conservation, water and air

quality) and social (hunting, landscape, recreation), as shown in the FAO/UN-ECE Forest Resource

Assessment of the Temperate Zones 1990 (UN-ECE/FAO, 1992 and 1993). Up to a point, increasing

demand for these can be satisfied without a significant impact on the forests' ability to supply wood, in

other words the forests' capacity to provide a range of goods and services is still being under-utilised,

even with sustainability criteria applied. In others, notably the transfer of productive forest to nature

reserves or other protection areas, a negative impact on wood supply is apparent.

Country situations differ vastly in this respect: the Netherlands, with its small forest area and high population density gives strong priority to the non-wood functions and has been prepared to rely heavily on imports and waste paper recycling for the bulk of its wood and fibre requirements. Finland is at the other extreme and has given priority in the past to the wood-producing role of its forests in order to furnish raw material for its export-oriented industries. Even in Finland, however, the widening gap between forest increment and fellings and the calls of the environmental lobby have activated a strong debate on the possibilities for and impact of allocating a larger area than at present of its forest resource to uses other than wood production (Finnish Forest Industries Federation, 1993).

The NGOs have been active in many countries, not only in the debate on the policy issues, but even in acquiring areas of forest for transformation into reserves or at least to manage in a multiple-use fashion. Typical have been the actions of the National Trust, Royal Society for the Protection of Birds and the Woodland Trust in the United Kingdom.

Another example of change in use without drastic change in land type or landscape is the growing use of rural areas for recreation and tourism (OECD, 1993k; UN-ECE, 1991d). By the year 2000 tourism will have grown to be the largest service industry in Europe and at least a part of the increase will have to be absorbed by the countryside, as tourist sites in the cities and on the coasts become saturated and people seek the relative tranquillity that the countryside can still offer. This will affect the way forests are managed, both those closest to the main conglomerations and those more distant, which form part of a distinctive landscape that is attractive to tourists. Much thought has been given by forest administrations and other managers on how to accommodate greater numbers of visitors without unduly adding to the conflicts with other functions, notably wood production, nature reserves, wildlife habitats and hunting. Tourism is seen as increasingly important to rural development, but there is also the risk, which can be partly avoided by careful planning, of despoliation of the countryside by an excess of visitors.

Policies seem likely to move in the direction of encouraging more forest tourism, but to try to concentrate this activity in certain areas. Some forest areas may in consequence lose some of their ability to perform other functions, including wood production. Some relief of the touristic pressure on existing forests may be achieved also by the creation of new forests within easy access of large conurbations, a policy already being implemented by a number of countries. The long-term nature of such initiatives needs, however, to be emphasised.

Another issue has been the measures taken to convert “unused” land into productive forest. Considerable areas of moors, heathlands and peatbogs have been drained and ploughed in preparation for afforestation, and this has accounted for part of the increase in forest area over recent decades. These developments are being more and more challenged on both environmental and economic grounds. In several countries, environmental impact assessments are now required before large-scale land use changes of this kind are approved (UN-ECE, 1992c). Afforestation of non-agricultural land is likely to be increasingly constrained in the future, except in instances where it is needed for non-wood functions.

Forestry as a possible aid to the maintenance of employment and the social fabric in the countryside has also entered regional development policy discussions. Situations vary from region to region, but in general not a very strong case can be made. Where forests already exist, intensification of forestry activities such as wood-harvesting may be achieved through mechanisation rather than increased employment. Elsewhere, investment in afforestation in terms of cost per additional worker may be high compared to alternatives, such as increasing tourist facilities, and may contribute to demand for labour more in the short than the long run. The case for forestry as an employer may be quite good in the southern parts of Europe, where problems of rural under-employment and depopulation are the most serious, and where the principal objective of afforestation and reforestation is often soil protection rather than wood production. Forestry development to provide rural employment may also become interesting in some of the countries with economies in transition as their structural changes affect present agricultural and industrial labour needs.

Wood-processing industries

Regional development is often concerned with decentralisation and the establishment of enterprises in

rural areas. In this respect, the wood-processing industries may have a positive role to play. There are

economic advantages in locating processing close to the source of raw materials. This may involve

longer distances for transporting the processed product to market, but the cost of this can be better

supported than that of transporting lower-value raw materials from the forest to distant industries.

Large wood-processing industries, such as pulp and paper, will be suitable for this purpose only where there is a large concentrated source of wood supply, and most of such sources already have industries located in the vicinity. On the other hand, sawmills and certain categories of wood-based panel plants with not too large, but economically viable capacities and local markets could serve a useful function in regional development, by providing employment not only directly but also indirectly in wood harvesting and transport and downstream industries. Tourism and increased leisure time should also encourage other small-scale activities, such as woodcraft artisans and the production of charcoal for camping and barbecues. There is ample availability of low quality and small-sized wood suitable for charcoal production in many countries, and this would offer good opportunities for better management of small forests, use of labour and increased income in rural areas.

All in all, the wood-processing industries could play a positive role as an instrument of rural and regional development. Or put the other way round, development policies could benefit from giving these industries a more active role than has usually been the case in the past. In several parts of Europe, investment in less favoured regions is being supported by grants and subsidies, for example by the European Community. However, such assistance has been directed more to primary activities such as agriculture, infrastructure and afforestation than to rural industries. Greater support for these industries, together with measures to improve access and infrastructure, could contribute significantly to rural development.

International trade in forest products

There do not appear to be close links between rural development and international trade in forest

products, but this may need to be examined further.

Markets and demand for forest products

Similarly, the link with markets and demand for forest products is, at first glance, not a strong one.

However, if regional development policies actively encourage the revitalisation of rural areas, this would

have an impact on construction in those areas. This would consist of new building, both of dwellings

and of service buildings, such as hotels, restaurants, visitor centres and other tourist facilities. Such

construction should be designed to blend with the landscape, and in many cases wood would be one of

the main building materials. The countryside is also becoming increasingly attractive to city-dwellers,

who are looking for secondary homes for weekends and holidays, and are ready to restore and convert

old houses or build new ones. Again, wood could be expected to be used to an appreciable extent in

such constructions for aesthetic reasons, and would also be one source of heating and cooking.

The influence of rural and regional development policies on demand for forest products is somewhat speculative, even if a positive link could be made between active development policies and increased wood use.

Over the past 30 years, world gross agricultural production rose by more than 100 percent, compared with a population expansion of about 70 percent (FAO, annual; FAO, 1983). This resulted in an increase in agricultural output per caput of nearly 20 percent. Food availabilities for the world as a whole are today equivalent to some 2700 kilocalories per person per day, up from 2300 three decades earlier. This excludes the cereals fed to livestock, part of which could theoretically be diverted to direct human consumption and bring the world average to above 3000 calories. The existing level of food availabilities per caput may be considered sufficient for everyone on the planet, provided they were distributed equitably.

Unfortunately, they are not. Per caput food availabilities in western Europe are some 3500 calories per day and in North America 3600. At the other extreme they are only 2100 calories in sub-Sahara Africa and 2200 in India and Bangladesh, and for a large part of the developing world availabilities are far from adequate for all people to have access to sufficient food at all times. It is too simplistic, however, to say that food security is not a problem of production but of distribution. A drastic redistribution of world food supplies by means of international trade is not realistic in the long term. At the root of the problem is a lack of purchasing power, in other words poverty, which results in food insecurity and malnutrition. Chronic under-nutrition affects some 800 million people, or 20 percent of the population of the developing countries. These are mostly the same countries where population growth is the greatest.

According to the latest FAO projections, growth rates of world agricultural production in the period 1990 to 2010 will be lower than in the previous 20 years (FAO, 1993h). This is largely a continuation of the longterm trend and the slowdown is not in itself an entirely negative outcome to the extent that it mirrors some positive trends in world demographic and economic development, notably the expected decline in population growth rates. On the other hand, the slower growth is projected to occur despite the continued existence of widespread malnutrition and largely because of insufficient incomes among the poorest segments of the population with which to buy food. Food output in deficit regions could undoubtedly be expanded at a higher rate than envisaged if effective demand were to expand faster.

FAO's latest projections are shown in table 4. The contrast between the growth rates in the developing and developed regions reflects those of population trends. The particularly marked change in eastern Europe and the former USSR, with slight declines shown for the period 1988/90 to 2010, is partly explained by the steep fall in output and consumption in the early 1990s which may not be completely recovered by the end of the projection period, and partly by the major structural changes occurring in these countries' agricultural sector.

| Total | Per caput | |||

| 1970 to 1990 | 1988/90 to 2010 | 1970 to 1990 | 1988/90 to 2010 | |

| (average annual percent change) | ||||

| Production | ||||

| World | 2.3 | 1.8 | 0.5 | 0.2 |

| - Developing countries | 3.3 | 2.6 | 0.5 | 0.8 |

| - Industrialised countries | 1.4 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.2 |

| - Eastern Europe & former USSR | 1.2 | 0.4 | 0.4 | -0.1 |

| - Other industrialised countries | 1.5 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.4 |

| Domestic demand (all uses) | ||||

| World | 2.3 | 1.8 | 0.5 | 0.2 |

| - Developing countries | 3.6 | 2.8 | 1.4 | 0.9 |

| - Industrialised countries | 1.2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.0 |

| - Eastern Europe & former USSR | 1.4 | 0.2 | 0.6 | -0.4 |

| - Other industrialised countries | 1.2 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.2 |

Source: FAO, 1993, Agriculture: Towards 2010.

Expectations regarding employment in agriculture are given in table 5. Active employment in the agricultural sector may grow, albeit slowly, globally and in the developing countries, but it is expected to continue to decline in the developed countries from the already quite small numbers in 1990. In the market economy countries of Europe (Turkey excluded), for example, agriculture may occupy only 3 percent of the total active population in 2010, compared with about 7 percent in 1990, while in eastern Europe the share may drop from 18 percent to 9 percent over the same period. Comparing output and employment trends, it can be deduced that the long-term increase in labour productivity in agriculture is predicted to continue.

Table 5: Economically active population in agriculture, 1990 to 2010 (forecast)

| TOTAL | Percent of total econ. active pop. | Average annual percent change | |||||

| 1990 | 1990 | 2000 | 2010 | 1980-1990 | 1990-2000 | 2000-2010 | |

| (mill.) | (%) | (%) | |||||

| WORLD | 1101.5 | 46.6 | 42.1 | 37.8 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 0.4 |

| - Developing countries | 1051.4 | 59.6 | 53.0 | 46.7 | 1.3 | 0.7 | 0.5 |

| - Industrialised countries | 50.1 | 8.3 | 5.5 | 3.6 | -3.3 | -3.6 | -3.7 |

| - Western Europea | 12.5 | 6.8 | 4.5 | 2.9 | -3.4 | -3.9 | -4.3 |

| - EC 12 | 9.3 | 6.0 | 3.9 | 2.6 | -3.4 | -4.0 | -4.2 |

| - Other W. Europea | 3.2 | 11.7 | 7.6 | 4.8 | -3.2 | -3.8 | -4.4 |

| - Eastern Europe | 9.1 | 17.9 | 12.6 | 8.8 | -2.9 | -2.8 | -3.1 |

| - Former USSR | 18.8 | 13.0 | 8.3 | 5.2 | -3.6 | -3.9 | -3.8 |

| - North America | 3.3 | 2.4 | 1.6 | 1.1 | -2.8 | -3.2 | -3.5 |

Source: As for table 4

a Excluding Turkey, for which the 1990 figures were 11.5 million economically active in agriculture, or 48.4 percent of the total economically active population.

While more difficult to measure, productivity in terms of output per unit area has also been increasing. This can be seen for Europe from the combination of the increase in production (table 4) and the decrease in the area of agricultural land (figure 15). The area of agricultural land in Europe has been declining: between 1983 and 1988 by an average of about 600,000 ha a year in Europe in total (FAO, 1992a). Up to one half of this has been the transfer to forest and other wooded land by afforestation or natural regeneration, and part of the rest to built-up areas. However, in recent decades transfer within the agricultural land base may have been more substantial than those between agriculture and other land uses. The most significant of the former has been the conversion of permanent pasture (grassland) to arable land. In France, for example, there was a net shift of 1.2 million ha from grassland to arable between 1982 and 1990, while there was a net loss of agricultural land in total to other uses of 350,000 ha (200,000 to built-up land).

Much of the agricultural land in Europe given up to other uses (or no use at all) has been abandoned by farmers and their families for economic or social reasons or old age. Families that have moved to cities may continue to own rural land but, if they cannot rent it to their former neighbours, it is left uncultivated. Such land is mostly of lower quality or in remote areas or both, but even good quality farming land in the vicinity of towns may be far more valuable for building and infrastructure and be sold up by farmers, even if they had been making a reasonable profit from agriculture.

Increased productivity has more than compensated for the loss of agricultural land in Europe, with the result that total production has steadily increased and in many western European countries has resulted in expanding food surpluses and export availabilities. Underlying the rise in yields, both of crops and animals, have been improvements in technology (breeding, mechanisation, etc.) and higher investments in fertilisers and pesticides. These in turn have been heavily supported by Government policies through guaranteed prices and the subsidisation of production, as well as of exports.

Biotechnology is still in its infancy, but it is already beginning to have an impact on agriculture. For the future, there are potentially major implications. It is likely to lead to greatly increased crop and animal yields and greater resistance to disease. From the management point of view, it could give rise to very concentrated, industrialised forms of agriculture, bearing little resemblance to traditional forms and radically change the structure of farming and rural economies in the coming decades. The concentration of biotechnological expertise in the hands of a small number of major companies could marginalise some of the existing forms of agriculture. The social as well as economic consequences could be immense. Serious questions may arise as to the acceptability of biotechnology from the environmental and sustainability points of view.

Another feature of the agricultural sector in western Europe has been increasing vertical integration. This has mostly occurred through the food processing industries and those providing agricultural inputs playing an expanding role in production, thus modifying the context of decisions about what is to be produced, and by what methods (varieties, strains, production techniques, fertilisers, pesticides, quality criteria, etc.).

The situation in central and east European agriculture has been completely different from that in western Europe, both before the events of 1989/90 and subsequently (FAO, 1992b, c and d). Under the centrally planned system, agriculture in eastern Europe had been largely concentrated in big State-owned or cooperative enterprises, one partial exception being Poland where about one third of the area remained in private hands. As at the macro-economic level, structural changes in agriculture since 1989 have followed different paths and time schedules, but have in all cases been aimed at moving towards a form of market economy, with liberalisation of prices, both of inputs and outputs, and towards privatisation. Especially with regard to the latter, progress has varied considerably. With increasing market liberalisation, agricultural wages, which under central planning were, at least in principle, equivalent to those in industry, have been falling behind.

Despite this and declining output, there is reluctance among farming people in the countries with economies in transition to move to the cities, partly because job-seeking is no better and often worse there than in the country. In some areas this is leading to forms of subsistence farming which, together with considerably reduced Government subsidies and levels of investment, e.g. in fertilisers and new equipment, has reduced productivity and profitability. The difficult situation for agriculture in these countries has been compounded by other factors, such as inadequate institutional infrastructure (banking, mortgage and insurance facilities, legal framework, etc.), bad weather conditions in some areas, notably serious drought in 1992 and 1993, and inadequate access to west Eurpean markets. Looking at the longer term, substantial areas of agricultural land, mainly of lower quality, will be abandoned in the countries with economies in transition.

Government intervention in agriculture has traditionally been more pervasive than probably in any other sector of activity. For much of the period following the Second World War, policies in all European countries were aimed at raising output, attaining a certain level of self-sufficiency in food and maintaining rural employment, income and living standards. Little consideration was given until relatively recently to environmental protection or sustainability, since up to certain levels of intensity of farming activity, these had not emerged as serious problems. Farming had been carried out for generations without visible deterioration of the land or landscape.

Government support in the form of guaranteed prices, loans, grants, subsidies and contributions to research and development, extension and marketing schemes, etc., led to a steady rise in productivity in terms of output per ha and per worker and to increasingly intensive forms of agriculture. In many countries this eventually resulted in the over-production and stock-building of certain food categories referred to earlier, as well as in negative environmental effects. Attitudes towards farming among the public and in the legislatures have gradually become less sympathetic to what is seen as over-generous use of taxpayers' money, and ways are being investigated to reduce the dependence of agriculture on public financial support. These attitudes are in contrast to the ever-growing support for the conservation of the environmental and aesthetic features of the countryside.

In many countries, farmers' associations still constitute a strong political lobby which, even in those that have become largely urbanised, retains a substantial level of support from the general public. Governments still find it necessary, therefore, to develop new policies towards rural development in general, and agriculture in particular, with due political sensitivity.

Government support has also been given through subsidies to agricultural exports as a means of disposing of domestic surpluses (FAO, 1988a). At the supra-national level, support both for domestic production and exports has been provided, in the case of the European Communities, within the framework of the Common Agricultural Policy [CAP] (CEC, 1991 and 1993f). A major part of the EC's total budget in fact goes into implementing the CAP and, as at the national level, considerable efforts are being devoted to finding means of reforming it (CEC, 1993c; FAO, 1992). This involves seeking to reduce the cost of the CAP and the market distortions it has created, whilst preserving such objectives as maintaining incomes and the social fabric in rural areas (OECD, 1992b and c). One way of doing this would be to switch support from forms that have an impact on food output, for example price guarantees, to direct income support (OECD, 1993a). This could allow support to be better targeted to specific categories of farmers, for example those in areas that are economically weak or whose land is providing or is capable of providing social or environmental services (CEC, 1993d). The problems lie in devising acceptable schemes, not least in changing the attitudes of farmers who have become used to existing forms of Government support and resent a dilution of their traditional farming activities. One impact of reduced support would be on the demand for and price of agricultural land.

Public debate about agriculture has been shifting with the growing realisation of the environmental damage being caused by certain, generally intensive, agricultural practices (FAO, 1992f and i; OECD, 1992b and d; UN-ECE, 1991; WWF, 1992f). These include the contamination of groundwater and hence sources of water for domestic use by improper or excessive use of fertilisers and pesticides; destruction of wildlife habitats and species of flora and fauna; loss of genetic and biological diversity; soil erosion, compaction or degradation; and water and air pollution from animal wastes. There has also been concern about the effects on human health of chemicals used in agriculture, both for growing cereals, fruit and vegetables and for augmenting yields of meat and other animal products (milk, eggs, etc.).

Organic farming has made progress in some countries, although its practice is being adopted on a piecemeal rather than a well coordinated basis. Several countries are providing farmers with assistance to ease the change-over from traditional to organic or “natural”farming methods. In some countries, animal rights movements are pressing for more humane methods of animal rearing, such as the banning of battery egg production (laying hens kept in small cages) and certain methods of veal- and pigmeat production. Measures to avoid environmental and nutritional damage include the banning of certain substances and practices, economic measures to restrict the use of fertilisers, pesticides and other chemicals, tighter controls of certain agricultural processes, reduction and better management and recycling of plant and animal wastes, e.g. for biogas generation, and product quality control. The impact is often to reduce yields per unit area or reduce the level of intensity of operation. Almost inevitably it also results in higher production unit costs.

The farming community, especially in western Europe, is therefore faced by pressures from several directions: over-production, biotechnology and other developments leading to higher productivity and/or intensity of output with consequent negative effects on prices and incomes; moves to reduce the level of Government support; and policies to direct agriculture into more environmentally and socially acceptable practices, including those that ensure sustainability. In the countries with economies in transition, these pressures have also been evident to a greater or lesser extent, but are currently being compounded or confused by the effects of the transition process, including privatisation.

With regard to alternative uses of agricultural land, one option is diversification, including the production of non-food crops, such as industrial raw materials (Alfons, 1991; CEC, 1993a; FAO, 1992a). Others are energy from biomass, farm tourism, various forms of recreation and leisure activities, e.g. golf courses, nature conservation and, as will be discussed in the next section, forestry. One controversial use, or rather non-use, of agricultural land is its subsidised temporary withdrawal (fallowing) from food production- “set-aside” - which is an important component of the reform of the CAP and is also practised in other European countries than the EC 12 as well as North America. It may be argued that set-aside is a form of direct support to the farming community and therefore consistent with the efforts to move away from price support, On the other hand, it does not offer a long-term solution to the underlying problem of food over-production; indeed, it delays finding more permanent solutions. It is also difficult to administer set-aside schemes and to avoid them being abused. Furthermore, farmers will, if they can, set aside their least productive land, to minimise the impact on their total output, which continues to be price-supported. Moves are being made within the EC to redefine the basis on which set-aside payments are made that would allow such land to be used for more permanent uses, such as afforestation. One problem to be overcome is the legislation that exists in some countries preventing land, once transferred to forestry, from being reconverted to its original use, should need arise.

Forest resources, forestry and wood supply

A distinction needs to be made between the implications for the development of the FFI sector in the

very long term and that in the period covered by ETTS V; and also between those affecting the sector as

a whole, including non-wood benefits of the forest, and the ones more particularly affecting wood supply.

Some of the expansion of forest and other wooded land in Europe has been as a result of natural regeneration, which may eventually finish up as forest, even productive forest or, depending on the site, as other wooded land; and some as afforestation (man-made plantations). For some time to come, it is expected that the area of land needed for food production will continue to decrease in most if not all European countries. That leaves unanswered such questions as: how rapidly will that development occur; how much of the surplus land will change or be changed into forest and other wooded land; and how much of that conversion will primarily be intended for the production of wood? Some attempts have been made to answer these questions, but it is doubtful whether they can be more than speculative.

The pace at which agricultural land will become available for other uses depends to a considerable extent on progress in reforming agricultural policies including, in the case of the EC 12, the CAP; and also on the outcome of international trade negotiations, notably the GATT Uruguay Round (see Section 2.8 on trade). It has been assumed that the successful result of the negotiations will eventually result in the release of 20 million ha from food production in Europe, but it is not clear whether this “guesstimate” refers to additional land to that which would have been abandoned anyway or what is the timescale involved.

In any event, in the light of the GATT outcome, it is probable that the optimistic scenario, the present rate of transfer- in the 1980s it was about 600,000 ha a year for Europe as a whole - of food producing land to other uses will accelerate. Among the factors that might slow down the rate of change, even in an optimistic scenario, could be:

Greater extensification of agriculture, to meet environmental and sustainability objectives. This could be achieved if the long-term downward trend of food prices was reversed.

Policies to retain more land in agriculture than is needed for food supply within the region, as part of a safety net for global food security. Even so, it is difficult to visualise under the optimistic scenario the rate of transfer dropping below that of the 1980s. At the other extreme, adoption of policies of afforestation on a major scale as a part of a global strategy to arrest the build up of atmospheric greenhouse gases, might just conceivably force more land, including some of good quality, out of agriculture and into forestry than would occur in the normal course of events.

While a pessimistic scenario need no longer be considered, assuming that GATT signatory countries will ratify the Uruguay Round agreement, completely free trade in agricultural products will remain a pipedream and some degree of protectionism will be maintained in Europe, as in most other regions, mainly for social reasons. Even if such protectionism should turn out to be greater than can at present be envisaged, the loss of land for food production is unlikely to be at a rate below that in the 1980s.

How much surplus agricultural land might become forest and other wooded land would depend on such factors as the attitude of farmers towards either disposing of their land or converting it themselves to forestry; the economics of forestry and its profitability as compared with alternative investment options; the encouragement given by Governments to afforestation; the development of the political debate on rural development in the context of sustainability, bio-diversity and climate change. On the negative side, farmers in some countries are frankly not interested in converting part of their land to forestry with the long delay involved before any financial returns can be expected. Furthermore, forestry has not shown itself to be a particularly profitable business and may not fare well as an investment choice. Thirdly, even where Governments are willing to support afforestation through grants or subsidies, levels of support will, in the financial climate likely to prevail in the foreseeable future, be considerably less than those applied to agriculture at the moment.