The industrial revolution, which began in the late 18th century following the invention of the steam engine, changed the production of goods from a largely artisanat-type operation to a massed-produced one within a factory system containing steam-driven machines and their human attendants. It brought with it a host of benefits as well as ills to society. A second revolution occurred with the advent of electricity a hundred years later. Perhaps we are in the midst of yet another one generated, on the one head, by rapid technological development in such fields as information and communications technology, space technology, advanced materials, flexible manufacturing, biotechnology, robotics and so on; and on the other by concerns for the environment, sustainability and the quality of life.

After the Second World War and up to 1973, world industrial output rose by an average of between 5 and 6 percent a year. Since the first oil price crisis of 1973/74 it has been growing at about half that rate, which is still a respectable performance by historical standards. In Europe, as in other regions that already had a well developed industrial base before the war, such as the United States, the structure of manufacturing has changed immensely, with certain traditional industries in sharp decline and new ones, including the so-called high-tech industries such as electronics and aerospace, and those based on biotechnology, taking their place.

Without going into detail, some of the main developments have been (Kennedy, 1993; OECD, 1991b and c; OECD, 1993a):

The pace of change is, if anything, still accelerating, and an industry that is not prepared or not able to adapt to changing market conditions will sooner rather than later fall out of the race. This is just as much true for the high-technology industries as for the more traditional ones, and places an increasing premium on the quality of management and of the workforce, as well as on design and quality of the product, stock-management and after-sales service. In some of these areas, many European countries have been at a disadvantage vis-à-vis other countries such as Japan. Indeed, a feature of recent years has been the adoption of Japanese industrial strategies and production management methods, including labour relations, in a number of industries in Europe, for example in the United Kingdom.

The extent to which the developments outlined above so far apply to the situation in the countries with economies in transition is limited. The situation there is totally different, and the problems being faced by their industries are generally more basic in nature. Industrial output has slumped since 1989, and many industries have been closed down definitively for lack of competitivity, failure to attract new investment for modernisation, loss of markets, or for environmental or other reasons. Foreign investment, together with transfer of technology and the setting up of international business ventures, has been slower to materialise than hoped for, despite the fact that wage levels are a fraction of those in the west (OECD, 1992d). There are several reasons for this, including unwillingness to invest in obsolescent enterprises and to accept the legal consequences of past environmental damage caused by them. Furthermore, the institutional, legal and even physical infrastructure necessary to allow an enterprise to operate efficiently has generally been lacking. In other cases, doubts about political stability and the ability of management and the workforce to adjust to a market-oriented situation have inhibited foreign involvement. No doubt this will change, and attractive opportunities for investment will increase, but the timescale involved may be lengthy.

Privatisation is also a complicated issue in the countries with economies in transition. All have accepted the principle of moving towards forms of a market economy, including privatisation of the means of production. In several countries, including Hungary, Poland and the Czech Republic, progress has been quite marked, especially for small and medium-sized enterprises. The breaking up into smaller units and their disposal to private buyers of the very large-scale State-owned industries that were a feature of central planning, however, pose major difficulties, especially since many of them were producing capital goods for which markets have declined or had a bad environmental record. Some of the Governments in these countries are still reluctant to allow foreign investors to establish greenfield industries before they have been able to dispose of these albatrosses.

The question of privatisation is by no means restricted to the transition countries. Many market economy countries have taken or are considering steps to privatise wholly or partly State-owned industries and services. The rationale varies, but underlying the move has been the intention to reduce the financial burden on the public purse of running loss making enterprises, to remove monopoly situations and to improve efficiency. Such sectors as coal-mining, steel-making, rail, road and air transport, ports, telecommunications, banking and dwelling construction have been among those to be privatised, but in some market economy countries the State has been directly involved in almost all sectors of the economy, including ownership and management of forests and forest industries.

As a result of the ending of the Cold War, attention has been given to industry conversion, that is the conversion of defence industries to peaceful purposes (“They shall beat their swords into ploughshares and their spears into pruninghooks”). This is a long and difficult process, not helped by the continuation of conflict in many areas of the world, including parts of Europe and the former Soviet Union and the continuing trade, legal or illicit, in arms. In the long term the conversion process is likely to lead to significant changes in the industrial structure of many countries and should, at least theoretically, allow the redirection of investment into more beneficial uses.

One of the major challenges facing policy-makers in the industrialised countries is for national policies to be kept up to date and cope with the rapidly evolving globalisation of industry (OECD, 1991 c; Stevens, 1991/92). For example, policies relating to competition need to take account of the way in which globalisation is re-shaping industry and markets. R & D and technological resources are concentrated in the major industrial countries and in a limited number of large multinational firms in a few leading industry sectors. This may raise barriers to market entry by smaller firms and exclude some countries and industries from participation in high-tech activities. Such firms and countries have to develop effective strategies involving linkage with leading firms and regions. Policies which promote rapid transmission of technology know-how can be effective, and these may include incentives for direct foreign investment and alliances with foreign enterprises.

With increasing global interdependence, economic and political forces outside the home country become more influential. Firms may have their headquarters in one country, but most of their operations outside it, and consequently have to take into account policy changes in all the countries concerned, as well as those in which they are marketing their products. Technological networking and joint ventures can shift the benefits of R & D efforts in one country to others.

Much of industry policy is supposedly designed to improve competitiveness by encouraging the entry of new competitors (foreign firms or new firms), lowering barriers to entry and reducing investment costs (OECD, 1991b and 1992f). It may also seek to promote economies of scale in R & D, production or marketing by encouraging collaboration and allowing mergers. These measures attempt to improve the functioning of the supply side of industry, while bringing benefits to the consumer by lowering costs and widening choice. With increasing internationalisation, however, policies to promote competitiveness must take into account potentially distorting impacts of domestic support measures, which are often difficult to avoid.

One example of this is the promotion of regional industrial development (CEC, 1992a and b). Incentives to locate industry in a particular area with the object of strengthening the economic and social welfare of its population may distort market competition and lead to an inefficient allocation of resources. When carefully designed, however, they may attract high added value and advanced activities which will form into self-reinforcing clusters of firms and institutions and attract foreign firms and develop international linkages. “Silicon Valley” in California was a early example of this. The problem is how to identify long-term potential strengths, build local resources and local infrastructure, including training and business support services, without distorting competition, and establish appropriate local government services.

The introduction of local content requirements, meaning the inclusion of domestic materials or labour in a product, by many Governments may be incompatible with policies to achieve global economies of scale and efficiencies, which are likely to require international sourcing. Local content requirements can be a source of friction between countries, as well as between countries and globalised firms.

Patenting and the protection of non-patented technical information is, on the one hand, a means of enabling firms to benefit from the fruits of their own R & D and, on the other, a means for the dissemination of technological progress, by providing a legally-controlled mechanism for doing so. Patenting requires the publication of information about new discoveries and developments, but it also provides, at least in theory, the basis for negotiating on a commercial basis for the transfer of production rights. It is in the interests of industries, especially those with strong R & D and innovative abilities, that international agreements on patents are applied as universally as possible, in order to avoid counterfeiting and illegal breaking of copyright.

Policies concerned with the reduction of environmental damage caused by industrial operations are being constantly tightened, with such events as UNCED providing new impetus. Environmental legislation if it differs in severity from one country to another, can easily distort competition by placing costs on production. For this reason, considerable efforts have been made by countries to negotiate multi-lateral agreements on environmental control policies and measures. Environmental questions figured prominently in the GATT Uruguay Round negotiations; and are included in the mandate of the newly created World Trade Organisation. Another point relating especially to the countries with economies in transition is that privatisation may further complicate the task of policing environmental protection control, which even before the transition process began had been a particular weakness.

Also as regards the countries with economies in transition, industrial policy is concerned primarily with ways and means for restructuring and modernisation, including setting up the conditions and infrastructure (in the broadest sense) that would attract investment and other types of foreign involvement, since availability of capital from domestic sources is very limited. In practice, this has meant that in the early phases of transition, more emphasis has had to be given to macro-economic changes that to industrial recovery, but at least the basis is being laid for the latter. Privatisation is basic to the whole movement towards a market economy. Also in western Europe, however, privatisation of State-owned industries and other enterprises such as telecommunications is being pursued in many countries with the purpose of improving public sector financing and budget balances and improving competition and efficiency through the removal of monopoly situations.

Forest resources, forestry and wood supply

Industry policies will affect the wood raw material function of forestry mainly through their impact on the

wood-processing industries, which will be considered in the next section. In fact, the impact is more likely

to be in the opposite direction, that is to say the situation and outlook with regard to the forest resource

and wood supply could have an influence on policies for the type and location of industry. Countries that

are realising that their wood producing potential is greater than previously estimated could seek to

promote the installation of new wood-processing industries or the expansion of existing ones to absorb

the extra supply potential. At the same time, such policies would contribute towards other objectives,

such as rural employment.

Wood-processing industries

With the exception of pulp and paper in those countries where these industries are major players in the

economy, as in Scandinavia, most industry policies as discussed above probably have a fairly neutral

impact on the wood-processing sector. Of the three categories of industry - high-tech, processing and

traditional - wood-processing falls mainly into the second and third, which generally do not much excite

the attention of the policy makers, except where they are large employers, or where the balance of payments

can be upset by changes in international competitive advantage. The textile industry is a case in

point.

The sawmilling industry in most European countries is still characterised by the large number of small to medium size units and under-capitalisation. The trend towards rationalisation, as a result of the closing of small and medium-sized mills and occasionally some big ones, has been going on for decades. At the same time, however, modernisation of the industry has been actively encouraged in several countries for a number of reasons, among which to maintain outlets for domestically produced wood raw material, the attainment of a certain level of self-sufficiency and as a means of assisting regional development. Despite the steady fall in the number of mills, total sawmilling capacity in Europe as a whole has not changed greatly: a few large new mills have compensated for the loss of numerous small ones. The total number of wood-based panel plants and pulp and paper mills in Europe has also declined (exceptions being medium density fibreboard [MDF] and oriented strand board [OSB] plants), but the numbers were rather limited to begin with. The scope for further rationalisation is becoming less, although the process of modernisation has been and will have to continue.

Part of this process has involved foreign investment, particularly in the pulp and paper sector. This has arisen from the increasingly intense international competition, notably between North American and Scandinavian companies, coupled with the progress in the unification of markets, such as the European Communities and the European Economic Space. This has led companies to establish or take over processing facilities within trading blocks to avoid tariff and non-tariff barriers. This is a typical example of globalisation, and the tensions which it can lead to at the industry policy making level. In some countries, policy makers, not to mention industry leaders, and labour unions, have found it difficult to come to terms with the “internationalising” of their businesses.

While generally speaking forest industries in Europe do not fall into the category of major international companies, those in Sweden and Finland have become so over the past decade as a result of mergers and acquisitions, both within those countries and abroad, particularly in the EC but also further afield. In this respect they are matching the big forest industries in North America. These companies, which may not number more than a dozen altogether, are examples of the globalisation of industry. Pulp and paper are at the core of these industries, but often they also incorporate forest ownership, other wood-processing industries and even non-wood enterprises. It is difficult to say how far the integration process may eventually go, but it seems probable that a sizeable number of small and medium-sized sawmills and even wood-based panel industries will be able to remain independent to a greater or lesser extent and find market niches and local outlets. Often, their long-term survival will depend on co-operative arrangements of one kind or another, such as in raw material procurement, marketing, R&D, etc.

Environmental protection policy issues affecting the wood-processing industries have already been considered. Two principal aspects may just be repeated here:

Pollution control. Increasingly severe national policies have been introduced to reduce water and air pollutant emissions. The extent to which industries have been aided by the State to achieve the standards required, and the standards themselves, vary considerably, which can seriously affect production costs and hence competitivity. Progress is being made towards harmonisation, for example within the EC, but a question mark remains over the transition countries' ability to achieve within a reasonable timeframe comparable levels of “clean” production;

Waste management and recycling. Policies to reduce waste and augment recovery may well have a significant impact on the wood-processing industries through changes in their raw material input mix (less virgin fibre), changes in processing technology (de-inking of waste paper, removal of contaminants, etc.) and location (possibilities to locate recovery plants near major consumption centres). Exporting companies are faced with the problem of complying with importing countries' requirements with regard to the content of recycled material in paper and paperboard, which can even lead to the former having to import waste paper and install appropriate processing plant. Wood residue-producing industries, notably sawmills, may find greater difficulties in disposing of them to pulp or panels industries. In some countries, the seemingly attractive option of using waste paper and wood residues for heat and power generation may be prevented by legislation on environmental grounds (CO2 emissions), which deserves further consideration.

In fact, there are signs that some of the legislation introduced in recent years with the worthy intention of improving environmental protection is proving unworkable, for example regulations in a few countries on the recovery of packaging material and other waste, which has often resulted in the build up of volumes far in excess of the capacity of recycling industries to handle them and a collapse of prices. Germany, for example, which has led the field on waste recycling legislation, has recently postponed the date of entry into force of new, tougher policies with regard to packaging recycling.

It is difficult to foresee how industry policy will evolve in the countries with economies in transition and how it may affect the wood-processing industries. Privatisation is continuing in all of them, but at different rates and with different degrees of success. Several of these countries have good availabilities of wood raw material and inexpensive but skilled labour which, if these could be combined with adequate investment for modernisation and development of the necessary experience to operate under market economy conditions, could place them in a good competitive position vis-à -vis their western counter-parts. East-west co-operation, including joint ventures, offers considerable scope, once western investors' hesitations with regard to such matters as the macro-economic and institutional framework have been removed.

International trade in forest products

So far as trade in forest products is concerned, European countries' industry policies should, if they were

successful, lead to stronger competition both between European companies and between them and their

overseas counterparts, both within Europe and in other markets. As noted in (a) above, the potential

availability of primary and recycled wood and fibre material may have more of an impact on European

countries' industry policies than vice versa, and consequently on their net trade balance in forest

products. In fact, the share of the region's net imports in total consumption has not increased in the past

decade or so. Laissez-faire industry policies would probably allow that trend to persist, while active

policies to promote the efficiency and competitivity of the wood-processing industries could even raise

Europe's self-sufficiency in forest products, either through import substitution or increased exports to

other regions or both. Obviously, to avoid difficulties in such for a as GATT, such support has to be

consistent with internationally agreed rules of competition.

Markets and demand for forest products

Policies aimed at industrial development may not have a significant impact on demand for forest

products, although there could be some effects on market creation and market expansion through, for

example, stimuli for construction activity increasing the demand for wood-based building materials. It has

also been observed, for example in the United Kingdom, which is heavily dependent on imports, that the

establishment of a plant producing a product, say particle board or MDF, that had previously to be

imported, often results in a noticeable increase in the total consumption of that product, and does not

necessarily lead to import replacement, unless there is a marked price advantage for the home-produced

product or “unfair” import barriers are erected. The home producer can benefit from lower stock-holding

costs, proximity to markets and the possibility to provide prompt service to the customer.

In the context of this study, “trade” is treated more broadly than as just the international exchange of goods and services. It will be convenient to cover in this chapter other factors that mark the relationship between countries, such as development aid, technology transfer, foreign investment and certain developments in other regions which have or may have an impact on their trade with Europe. In the FFI sector, the most obvious example is the exploitation of natural and old growth forests in both the tropical and temperate regions, partly to provide forest products to world markets.

International trade itself forms one of the major mechanisms through which national economies are linked. Europe's importance in global trade is shown in table 6. The region's exports and imports accounted for not far short of half of the world total in 1990, although it should be noted that an appreciable part of this was intra-European trade (Central Planning Bureau, Netherlands, 1992). Even with intra-European trade excluded, the region's trade with other regions was a significant element in the total of inter-regional trade.

Table 6 : Merchandise trade by main exporting and importing areas in 1990

| To: From: | WORLD | West Europe | Transit. countra | Former USSR | North America | Japan | Rest of world |

| (percentage of total world trade) | |||||||

| WORLD | 100.0 | 44.2 | 3.1 | 3.7 | 21.2 | 6.8 | 21.0 |

| W. Europe | 43.8 | 31.3 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 4.6 | 1.0 | 5.3 |

| Trans.countr.a | 3.3 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 2.1 | -- | -- | 0.2 |

| Former USSR | 3.5 | 1.2 | 1.8 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.3 | |

| N. America | 18.0 | 4.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 6.3 | 2.4 | 5.0 |

| Japan | 8.9 | 1.9 | -- | 0.1 | 3.5 | -- | 3.4 |

| Rest of world | 22.5 | 5.2 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 6.7 | 3.3 | 6.8 |

Source: As for table 3.

a Albania, Bulgaria, former CSFR, Hungary, Poland, Romania.

Based on the same source as table 3, four scenarios of European and world export growth between 1990 and 2015 are shown in table 7 (Central Planning Bureau, Netherlands, 1992). Scenarios of the average annual growth rates of western European exports vary from 3.1 percent per year (global crisis scenario) to 6.4 percent (balanced growth scenario); those of the countries with economies in transition (including the former Soviet Union) from 0.4 to 5.4 percent per year. These compare with scenarios for the growth of world trade ranging from 3.7 to 6.8 percent per year. Even in the global crisis scenario, trade is expected to grow more strongly than GDP, despite the increasing trade tensions, protectionism and olarisation into a number of powerful trading blocks envisaged in this scenario (which hopefully will not materialise).

Table 7: Scenarios for export growth, 1990 to 2015

| Western Europe | Transition countries incl. former USSR)a | WORLD | |

| (average annual percent change) | |||

| Scenariob | |||

| “Global shift” | 3.4 | 1.7 | 5.9 |

| “European renaissance” | 5.1 | 5.1 | 5.4 |

| “Global crisis” | 3.1 | 0.4 | 3.7 |

| “Balanced growth” | 6.4 | 5.4 | 6.8 |

Source: As for table 3.

a Albania, Bulgaria, former CSFR, Hungary, Poland, Romania, plus former USSR

b See footnote a to table 3.

The dynamic growth of international trade over much of the period since the Second World War can be largely attributed to policies, led by the major trading nations, to liberalise trade through the reduction or removal of tariff and non-tariff barriers (Abel and Kleitz, 1991). At the global level, this has been conducted principally through GATT (GATT, 1986). Regional groupings, such as the EC, EFTA (European Free Trade Association) and CMEA (Council for Mutual Economic Assistance, now defunct) have likewise served to stimulate trading between their respective member countries, which has contributed to global trade expansion to the extent that it has not involved raising barriers to imports from third parties.

The latest round of GATT negotiations, the Uruguay Round, culminated in an agreement, signed on 15 December 1993 by the contracting parties, which still has to be ratified by their Governments. The final act of the agreement was signed by participating countries at a conference in Morocco in April 1994, and its implementation will begin in 1995 and will include the replacement of GATT by a new body, the World Trade Organisation (WTO). While it is too soon to assess the full impact of the agreement, there seems no doubt that it will provide a significant stimulus to international trade in the medium to long term, notably as a result of the comprehensive and significant lowering of tariffs over the coming years. The scope of the Uruguay Round has been considerably extended, compared with earlier negotiations, to include such matters as trade in services, trade-related intellectual property rights and trade-related investment measures. While a major step towards the further liberalisation of international trade, the GATT agreement will not remove all protectionism. It is perhaps remarkable that it did achieve a considerable degree of success, given that the negotiations took place during a period of recession in many of the leading economies.

One area receiving increasing attention is trade-related environmental policies (WWF, 1992a, b, c and e). Long before the UNCED Conference, the potentially negative as well as positive impacts of environmental issues on trade, and vice versa, began to be appreciated (Peck, 1991). One aspect is the damage that can be done to the environment through export-related activities: commercial logging of natural forests is a frequently cited example. Another is the “exporting” of environmental problems by the relocation of industrial activities in less environmentally sensitive areas, which in practice may be areas where the green movement has yet to become politically assertive. Yet another is the claimed gaining of unfair competitive advantage of having lower environmental standards.

Various trade measures have been considered, and some introduced, to protect the environment (CEC, 1992; WWF, 1993f). CITES, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species, contains lists of such species of fauna and flora that it is illegal to trade in, alive or dead. Initially used in an effort to avoid the extinction of rare and threatened species by banning trade in, for example, tiger skins, rhinoceros horns and elephant tusks, the scope has widened to the extent of including a number of tropical tree species that are in danger of disappearing.

Some countries have considered the unilateral restriction or banning of imports of products that are not produced in an environmentally or sustainably sound way. The underlying philosophy applied by GATT to such measures is that they should not be discriminatory (GATT, 1986). Thus, the mandatory certification or labelling of products as coming from a particular source or produced in a certain way is not acceptable under GATT rules because it discriminates in favour of other sources or methods. Furthermore, certifying the source of origin is far from easy to apply, since it is difficult to control and liable to abuse.

Another point to consider is whether a trade measure makes sound economic sense. In the case of import bans on wood products, the likely effect would be to force prices down and thereby lower the value of the resource from which the products come and increase the chances that it would be converted to some other use. In general, GATT encourages countries to use tariffs as being a more effective tool of trade policy than other kinds of measures such as quantitative restrictions.

Foreign investment and trade are closely related (UNCTAD, 1993). The former may be made with a view to substituting imports in the recipient country with domestic products, in which case its impact on trade may be to reduce it. Alternatively, its purpose may be to increase output intended for export by the recipient countries. There may be other reasons for foreign investment. One is its possible role of providing employment in the recipient country with the intention of reducing emigration pressure and its corollary, less immigration problems in the fund-supplying country; another is to take advantage of lower production costs elsewhere; yet another is to set up manufacturing in an area with less stringent environmental protection laws. Wherever the result is likely to be an increase in trade, it is important that consideration is given to whether import barriers exist in the investing or other potential importer country that could nullify or reduce the benefits to both investor (returns on investment) and recipient (increased employment, export earnings, etc.) from the investment.

Foreign investment, as discussed above, is understood to be financial transfers mainly, but not entirely, from the private sector. Another form of transfer is development aid, aimed particularly at developing countries, although at present also being directed to the countries with economies in transition. The sources of aid are diverse, ranging from government agencies to charities, and on a multilateral basis, governmental and non-governmental international organisations. In the recipient countries, the uses to which this aid is put is even more varied and only a part of it is trade-related, that is, it is directed either to industrial development or associated infrastructure, such as energy supply, communications and ports. The underlying objective is to assist in the improvement of living standards, by addressing the problems of employment, health, education, habitation or other aspects.

Financial transfers, whether as investment or aid, have certainly contributed to world economic development since the Second World War. It would be idle to pretend, however, that they have always been successful in achieving their objectives or beneficial to the fund providers and recipients. Problems have sometimes been caused as a result of faulty planning and execution of projects, and misallocation of resources. There was often a tendency in the past to ignore or underrate the environmental impacts, typical examples being hydro-electric schemes and oil and gas exploration. Nor has overseas aid for forestry and forest industry development been free from criticism in this respect. To some extent, the lessons from past errors have been learned, and vetting procedures, including pre-investment environmental impact assessments, have been introduced to ensure the better use of investments from the economic, social and environmental points of view.

It will be some time before the likely impact of the outcome of the Uruguay Round negotiations of GATT on the FFI sector can be properly assessed. This should be borne in mind in reading what follows.

Europe's imports of forest products from other regions have exceeded its export to other regions in recent decades by a ratio of three or four to one, leaving Europe as one of the two main net importing regions of the world (the other being East Asia). Europe's imports of forest products from other regions have been of the order of 60 to 80 million m3 EQ6 a year in recent decades, and the ratio of these imports to total consumption has remained fairly constant at between 15 and 20 percent (Peck, 1989). In order of importance, the main suppliers to Europe have been North America, the former USSR and tropical countries. Supplies from North America have been mainly in the form of semi-processed (sawnwood, woodpulp) and processed (wood-based panels, paper and paperboard) products; those from the other regions largely but not entirely in the form of roundwood and semi-processed products.

Tropical hardwoods have been imported and used in Europe for generations because of their decorative values in furniture and other aesthetic uses, complementing a number of temperate species used for these purposes. Since the Second World War, their use has extended into more utilitarian areas, as other properties such as natural durability, workability and freedom from knots came to be appreciated: these uses included interior and exterior joinery, where they have competed actively with temperate timber, both hardwood and softwood. In some countries, wood-processing industries were established specifically to convert imported tropical logs into sawnwood, plywood and veneers.

Intense discussions have taken place in many for a on the problem of tropical deforestation and how to deal with it (CEC, 1992c and 1993e; ESE, 1992; FAO 1993a). Here, we should note the ever-increasing pressures, in both exporting and importing countries, for the conservation of at least part of the remaining areas of natural tropical forest, notably for reasons of preserving bio-diversity, and to place the rest under forms of sustainable forest management involving multiple use including wood production. These pressures have been reflected in the positions taken with regard to trade in tropical forest products by, inter alia, GATT, UNCED in its statements of principles relating to forestry, the UN-ECE Timber Committee, ITTO and the European Parliament on supply from sustainably managed forests, as well as in conventions such as CITES.

As for trade, Europe has been importing around 12 million m3 EQ a year of forest products from tropical regions in recent decades, mainly in the form of hardwood roundwood, sawnwood, plywood and veneer sheets, but with an increasing trend towards further processed products, such as building components and furniture, as well as woodpulp from tropical plantations. Imports of roundwood (sawlogs and veneer logs) have been gradually declining and have been replaced to a greater or lesser extent by semi-processed and processed products. Since logs have come mainly from Africa and more processed products from South-East Asia and woodpulp from Brazil and elsewhere, there has also been a marked change in trade patterns.

Availability of tropical hardwoods in log and semi-processed form to the European market is likely to continue to decline gradually over the long term, and may be replaced only partly by increased supply of value-added products (Peck, 1993). This decline will be the result of a combination of factors, including reduced physical availability, policies in producer countries to put forest management on a sustainable basis, and their own growing needs for timber. Prices will rise in real terms better to reflect the environmental as well as economic cost of production on a sustainable basis. This will mainly affect sawlogs and veneer logs and their products and assumes that the possibility of replacing them with timber from tropical plantations on a substantial scale is not realistic, at least within the timeframe of ETTS V. The situation for products derived from lower quality wood (construction grade sawnwood, pulpwood, woodpulp, paper and paperboard) is quite different. Brazil and some other tropical countries, as well as Chile and New Zealand, have already demonstrated the potential of fast-growing plantations of exotic species and export-oriented industries based on them.

Besides supply-side constraints on trade in tropical hardwoods, importing countries in Europe and elsewhere have been considering the need for discouraging or banning their import and use with a view to halting tropical deforestation. In some countries, measures have been taken by municipal authorities to exclude the use of tropical hardwoods in public construction. A number of retailers will not sell furniture and other wooden articles made with these species, or they at least require a certificate of origin stating that they come from a sustainable source. Such voluntary arrangements fall outside the scope of international agreements, such as GATT, but official restrictions or banning of imports would only be possible if the measures applied were non-discriminatory. So far, such measures have not been introduced by European countries, but several possibilities are under consideration. Even without such measures, the climate of public opinion regarding the use of wood from non-sustainable sources has changed considerably over the past decade or so, even though there is still confusion over the concept of sustainability.

The debate on sustainability and bio-diversity of forests, which was originally centred on the tropical forests, is being extended to temperate and boreal forests (Sharma, 1992). Considerable controversy has been generated along the northwestern seaboard of the United States and Canada over the cutting practices-large-scale clear-fellings - and damage to wildlife habitats and the environment in general (Dietrich, 1993; Dudley, 1992). The problem became encapsulated in the “northern spotted owl” controversy, which has paralysed logging activity over large areas of publicly-owned prime growth forests in Oregon and Washington States, the closure of many forest operations and mills and the loss of thousands of jobs (Dietrich, 1993). The spotted owl became the symbol of a much larger issue concerning the preservation of the nation's remaining undisturbed forests, and the costs that this would entail in terms of job losses and higher prices of forest products to the consumer.

British Columbia, which accounts for about half Canada's wood supply, has been affected in much the same way, and it is doubtful whether environmental pressures will allow any further growth in wood production there: in fact, a decrease is more likely.

With regard to the other major softwood supplier, the Russian Federation, which holds more than a fifth of the world's forest resources and two-fifths of coniferous reserves, the story has been quite similar to that in parts of North America, with indiscriminate clear-felling followed by inadequate regeneration. The European part of the country, with one quarter of the forests and three quarters of the population, has been over-exploited. A major part of the forests in the remainder of the country, Siberia and the Far East Region, remains intact, partly because it is largely inaccessible. In some of the more accessible parts, however, heavy cutting has occurred, and insufficient care has been taken up to now with regard to environmental protection, bio-diversity and nature conservation. Increasing pressure in this direction will be set against the urgent needs of development and for hard currency from the export of timber and other commodities.

Overall, however, it seems unlikely that the Russian Federation will have the capability to restore, in the foreseeable future, its forest products exports to the levels that had been attained by the former USSR. To do so, major investments in infrastructure and industry would be necessary, and such investments would have to come mainly from abroad.

Forest resources, forestry and wood supply

Europe thus seems to be faced with the prospect of the availability of supplies from other regions at best

maintaining their current share of its demand for forest products, with the likelihood that the share and

even the total volume could decline. One exception to this is the supply of products from plantation-grown

timber in the tropics and sub-tropics, which are mainly at the lower end of the quality scale. It is

also in the raw material for these products that Europe itself is in surplus (small-sized roundwood, waste

paper etc.).

On the other hand, forestry in Europe may be faced with increasing demand for the higher qualities of roundwood as substitutes for timber from tropical and other external sources. This would be both for decorative species, such as walnut, cherry, oak and others, and for better qualities of utility timber, where both hardwoods such as beech and conifers could have a role to play. Within the ETTS V timeframe, there would be little scope for raising availability by new planting, but this could be of interest for the longer term. At the same time, European forests, especially the broadleaved (hardwood) component, are currently under-exploited and measures could be made to improve the marketing and increase the supply of existing resources. The extent to which European foresters can take advantage of this situation will depend to a large extent on their ability to keep their products competitive, both with products from overseas (North American hardwood suppliers, for example, have a substantial and, with appropriate management, sustainable resource reserve and are seeking to expand export markets) and with other wood products derived from lower quality raw material such as MDF and other panels, as well as non-wood products.

The implications of what has been discussed above relate to the strategies to be applied to both the volume and the quality of wood produced in Europe. Overseas supplies of forest products account for a relatively modest share of Europe's total market. An appreciable part of those supplies, namely those at the top end of the quality scale, are expected to become increasingly scarce and/or costly in the future. European countries' silviculture should therefore be oriented more towards the cultivation of higher qualities, which has implications for such practices as thinning and brashing (pruning) and, looking to the longer term, for the selection of species for regeneration, planting distances and so on; also for the financial results. Quality production, for example from long rotation hardwoods, generally results in lower return on capital, but sometimes higher net income per hectare per year. At the same time, silvicultural systems will need to limit the production of small-sized and lower quality wood, given the much greater potential for the mass production of wood fibre in other regions more cheaply than in Europe, as well as the greater use of secondary fibres (waste paper, etc.). The twin objectives of higher volumes of good quality wood and at the same time lower volumes of other qualities may be easier to achieve in theory than in practice: there is need for more research in this field.

Such a shift in emphasis towards quality is consistent with policy objectives related to the environment, sustainability, bio-diversity, landscape and alternative uses of agricultural land. With regard to the last, such a strategy would probably be more acceptable to both landowners and the public than one aimed at largescale wood fibre production, although for the former, the timescale for expectations for financial returns would have to be in terms of generations rather than decades, which has implications for the scale of incentives needed to induce them to plant. At the same time, it could open up possibilities for agro-forestry or the planting of quality timber species that might also provide returns within a reasonable period from fruit or nut production, such as walnut and chestnut.

Wood-processing industries

The structure of the sawmilling, plywood and veneer industries in several countries that have been

heavily dependent on imported sawlogs and veneer logs has been undergoing marked changes in recent

decades. Some of them have had to close down in the face of decreasing supplies or increasing

competition from imported sawnwood, plywood and veneers and further value-added products, or have

partly switched to domestic sources of supply of raw material. Industries in a few countries, including

France, Spain and Italy, have continued to import sizeable volumes of logs from the tropics, but in due

course as they become increasingly exposed to the winds of trade liberalisation they may have to adapt,

as those in other parts of Europe have already been doing.

One form of adaptation to changes in the origin and quality of raw material supply is to develop and market products that can compete with “traditional” products but are produced from lower quality materials. The classical example of this is MDF (medium density fibreboard), which in a relatively short space of time has gained a significant place as a substitute for sawnwood and other wood-based panels in certain end-uses. Engineered wood products, such as glulam, finger-jointed sawnwood, etc., also allow lower quality timber of short lengths to be used in technically advanced ways. The quality of melamine and plastic surfacing materials and printed paper overlays has improved tremendously, to the point where it can be difficult to distinguish between imitation and real wood veneers. These overlays on substrates of wood-based panels are finding increasing acceptance as replacement for solid wood for some decorative uses in the furniture and furnishing markets. But for many customers, solid wood will remain the preferred choice, if the price is right and - of increasing importance - it is shown to have come from a sustainable source.

The geographic distribution of the wood-processing industries in Europe may be affected by foreign investment and aid. In the past, some companies set up manufacturing facilities in tropical countries, which resulted in a shift in the commodity pattern of trade from logs to semi-processed products. Currently, there is increasing foreign interest in investing in eastern Europe, partly because of low labour costs but also because there are good market prospects there in the medium to long term.

International trade in forest products

Forest products are relatively lightly affected by tariffs and quantitative trade restrictions; indeed, much

of Europe's trade in these products is free of such restraints. However, as in most sectors, tariff

structures on forest products are progressive, becoming more restrictive with the increasing degree of

manufacturing and added value. Consequently, the successful outcome of the GATT Uruguay Round,

with a substantial across-the-board reduction of all tariffs, should lead in the medium term to improved

access to European markets for processed forest products, including furniture, prefabricated buildings,

building components, doors, etc. It is another question whether some overseas suppliers will still be in a

position to take advantage of greater access for their products, because of declining availabilities of raw

material and growing domestic markets. The trend will be more towards replacing their traditional exports

of logs, sawnwood, plywood and veneers with value added products representing a smaller equivalent

volume of wood. There would also be greater opportunities for European exporters. It is worth recalling

that Italy, while a major net importer of forest products in volume terms, has a positive trade balance in

wood and its derivatives in value terms, because of its substantial exports of furniture.

The success of the Uruguay Round should also provide a stimulus to trade in forest products through the boost it is expected to give to the world economy.

With regard to trade and the environment, restrictions on the exploitation of the remaining natural forests in different regions of the world and the application of guidelines for sustainable forest management are likely increasingly to limit the availability of certain wood products for exports from the tropical and temperate zones alike. The impact on trade with Europe is already evident for exports from the major tropical sources and parts of North America. It can be expected that a similar trend will emerge in due course in the trade with the other major supplier from natural forests, the Russian Federation. Here, however, other pressures, such as the need for foreign currency, as well as the present weakness of legislative control on harvesting activities, could delay the move towards applying strict environmental controls.

On the import side, there is movement towards acceptance of the principle of eco-labelling of forest products (see following sub-section). An example is the Regulation of 23 March 1993 on an EC eco-label award scheme adopted by the Council of the European Communities (EC, 1993). The effect would be to restrain demand for products which cannot be shown to be environmentally benign at whatever stage of their life cycle and from a sustainable source, and this would be reflected in the reduced volume of imports of such products.

Markets and demand for forest products

The successful outcome of the GATT Uruguay Round should act as a stimulus to world economic

growth, which would imply a corresponding acceleration in the consumption of forest products. Either

way, however, it would probably take some years for the effects to become fully apparent.

Eco-labelling is not intended to act as a ban on the use of products not meeting the required environmental criteria, but rather as a deterrent. As such, it is likely to be taken heed of by specifiers and users of materials, as well as wholesalers and retailers. It would also no doubt be used as a campaigning tool by environmental “watchdogs”. So far as forest products are concerned, the biggest issue, is the exploitation of natural or old growth forests and the extent to which it conforms, or can be adapted to conform, with criteria for environmental protection and sustainable forest management. Coupled with restrictions on the supply side, measures on the demand side will inevitably lead to some lowering in the consumption of forest products from what are deemed to be non-sustainable sources.

Construction accounts for between 10 and 16 percent of European countries' GDP (UN-ECE, annual b ) (figure 16). It is treated separately from the overall economy (Policy area B) in this study, however, for a number of reasons. One is that, as the major end-user of many forest products, policies affecting construction have a direct and immediate effect on the FFI sector. Another is that the trend of development of the construction sector has in many countries differed from that of the overall economy over the past two decades. And thirdly, fiscal and monetary measures have often targeted construction, implicitly or explicitly, as a tool for effecting counter-cyclical policies, with the result that business cycles in the construction sector have often fluctuated more strongly than in the economy as a whole and have led or lagged behind other sectors.

During the third quarter of the 20th century, construction maintained, and in many countries increased, its share of the strongly growing GDP in Europe. War-torn Europe had to be reconstructed, industries and infrastructure had to be modernised, and the lag in the rate of investment in construction, which had been restricted to a minimum during the hostilities, had to be recovered afterwards. As in many other sectors of the economy, the first oil price shock in 1973–74 marked a turning point for construction but, whereas the overall economy recovered from the mid-1970s recession and GDP growth resumed, even if at an average rate below that of the post-war boom years, construction slowed down markedly, and in the case of new dwellings began a decline which has continued into the early 1990s. There were exceptions to this general trend, as can be seen in figure 16. The share of construction in Sweden and the United Kingdom in total GDP was the same in 1990 as 1980, and it increased in Spain, whereas there were appreciable falls in its share in France, Germany and Italy.

Figure 16: Share ot total construction in Gross Domestic Product in selected countries, 1980 and 1990

Source: UN-ECE, 1992

The respective shares of the different parts of the construction sector in thirteen western European countries in 1990 are shown in figure 17 (EUROCONSTRUCT, 1991). New construction accounted for about two thirds of the total value of construction, more or less equally divided between three groups: residential construction and non-residential construction and civil engineering. Renovation and modernisation accounted for the remaining third. Unfortunately, data are hard to come by that clearly show the trend of investment in the different construction groups, but it would appear that in quite a number of countries, the share in new construction, both of dwellings and other types, has declined in the past decade or more, while that in renovation and modernisation of existing stock and infrastructure has risen. The data for 1980 and 1990 of Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF) in residential and non-residential buildings as a percentage of total GFCF in construction, shown in figures 18 and 19 respectively for a few countries, are indicative rather than conclusive in this respect. For residential construction especially, they mostly show a decline over the decade, inferring that the share in civil engineering and in renovation and modernisation combined increased.

Figure 17: Share of value of construction, by sector, in 13 European countries (A, B, CH, D, DEN, E, FIN, F, I, NL, N, S, UK) in 1990

Source: Euroconstruct, 1991

Figure 18: Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF) in residential buildings as share of GFCF in total construction, 1980 and 1990

Source: UN-ECE, 1992

Figure 19: Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF) in non-residential buildings as share of GFCF in total construction, 1980 and 1990

Source: UN-ECE, 1992

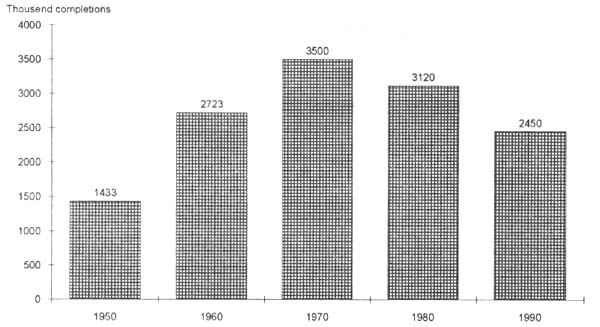

The trend for dwelling contruction in Europe shown in figure 20 is partly based on estimates (UN-ECE, annual b). Nonetheless the long-term evolution of new dwelling construction is clear. After rising by 90 percent in the 1950s and a further 29 percent in the 1960s (and reaching an all-time high in 1973/74), dwelling completions in Europe fell by 11 percent in the 1970s and a further 21 percent in the 1980s, the trend continuing in the early 1990s. Completions of the order of 2.5 million in 1990 were even below those of 1960. The downward trend over the past 20 years reflects the fact that by the early 1970s the post-war housing shortages had been filled in most countries and that the growth of population and household formation had slowed down markedly. In eastern Europe, where housing shortages remain or at least the quality of housing is in considerable need of improvement, the number of dwellings completed in 1990 was already little more than half the level in 1980; most of these countries have witnessed further steep declines since 1990 in line with the shrinking of their economies during the initial phase of structural reform.

Figure 20: Dwelling completions in Europe

Source: UN-ECE/FAO, 1975; UN-ECE, 1992

Some examples can be seen in figure 21, which also shows that in western Europe trends were mixed, with a few countries such as Finland, Sweden and Swizerland completing more dwellings in 1990 than 1980, which was contrary to the more general trend, as indicated by France and the United Kingdom.

Figure 21: Dwelling completions in selected countries, 1980 and 1990

Source: UN-ECE, 1992

With regard to the average size of dwellings, the trend for new construction in many countries has been towards smaller units, which can be seen in figure 22 showing the share of dwellings with 3 rooms or less. This can probably be correlated with the trend towards smaller family units and the increasing number of people living alone, as discussed in Section 2.1. Thus, not only has the number of new dwellings been falling, but their average size as well.

Figure 22: Share of dwellings completed with 3 rooms or less in selected countries, 1980 and 1990

Source: UN-ECE, 1992

In earlier sections attention was drawn to the population drift from the countryside to towns, and it might be expected that this would be reflected in an increasing share of dwellings being built in urban areas. At least during the 1980s, this does not appear to have generally been the case, as seen in figure 23. Maybe one reason for this has been the possibility afforded by increasing standard of living, improved infrastructure and greater mobility to indulge preferences to live in areas outside cities' perimeters but within commuting range. In this connection, there is doubt about the comparability of the statistics separating urban from rural construction. The low percentage of less than one quarter of urban dwelling construction shown for Germany, for example, relates to buildings in cities that are also administrative districts, which presumably excludes towns below the size of cities.

Figure 23: Share of dwellings completed in urban areas in selected countries, 1980 and 1990

Source: UN-ECE, 1992

On the basis of the evidence summarised in figure 24, most countries saw the public sector taking a declining share of total housing during the 1980s, although there were exceptions such as Finland and Switzerland. The more general trend may be explained by the tendency, which became increasingly marked during the decade, for the state to reduce its direct role in the economy and to encourage private enterprise to become more involved in certain sectors, housing being an obvious one. Public housing proved to be a heavy burden on the budgets of local authorities in many countries. This trend was occurring in both west and east European countries, in the latter even before the transition process began. In those countries, it may become more apparent during the 1990s as the process of structural reform, including privatisation, gathers pace.

Figure 24: Share of publicy built dwellings in total completions in selected countries, 1980 and 1990

Source: UN-ECE, 1992

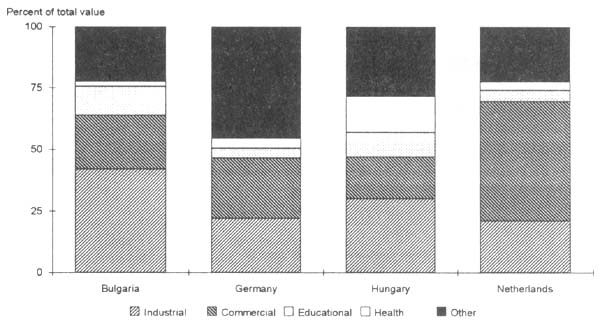

Information is poor in many countries on developments in construction sectors other than housing. Figure 25 shows the pattern of investment in new non-residential buildings for a few countries, which is useful in indicating the wide variations that exist. In Bulgaria and Hungary, for example, the share of the value of new industrial buildings is higher than in Germany and the Netherlands, where commercial buildings take a larger percentage of the total. Buildings for education and health account for relatively small shares, except in Hungary where between them they make up a quarter of the total value, compared with less than 10 percent elsewhere. “Other” sectors, which, include buildings for agriculture, religious worship, sport, etc., have a particularly large share in Germany - 45 percent of the total in 1990.

Figure 25: Value of new non-residential building completed by sector in selected countries in 1990

Source: UN-ECE, 1992

Medium to long term forecasts (the ETTS V timeframe) for the construction sector in Europe are apparently non-existent. Construction is a cyclical business, and is subject to influences, besides the economic ones, of a political and social nature which are difficult to predict.

A basic government objective in all countries is to seek to provide the population with adequate and improving living conditions. One of the principal planks of such a policy concerns construction in general and housing in particular. This is encapsulated in the UN International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, Article 11 of which states: “The States Parties to the present Covenant recognize the right of everyone to an adequate standard of living for himself and his family, including…housing, and to the continuos improvement of living conditions. The States Parties will take appropriate steps to ensure the realization of this right…” (UN-ECE, 1993c). European countries have been able to progress further along this road than many of those in other, less favoured regions, but most still have a long way to go.

After the Second World War, housing policies were most immediately concerned with quantity rather than quality (UN-ECE, 1976). As a consequence, large numbers of dwellings were erected, many in large-scale, high-rise buildings in or on the periphery of cities, and of indifferent quality. The supporting infrastructure and amenities were frequently overlooked (UN-ECE,1986a). Once the basic shortages had been satisfied, by the early 1970s in most countries, the emphasis of policy began to change towards quality, including the amount of living space per person, the provision of essential (water, heating, electricity, sewage facilities, etc.) and also less essential services, and a shift began in new construction towards a higher share of terraced or detached houses at the expense of high-rise blocks, which had been coming under increasing criticism, mainly for social reasons (UN-ECE, 1991c). More attention also was paid to the external living conditions, including local shopping facilities, play areas, gardens, parking space and cultural and sporting amenities (UN-ECE, 1988a).

More recently, further shifts in policy have become increasingly apparent. These have included giving more attention to social and environmental considerations, such as safety, health, and energy conservation (UN-ECE, 1992a, g, h and i). They have also meant giving more attention to the wishes of the consumer and more particularly of those with special needs so far as accommodation is concerned, for example the elderly, disabled, single-parent families, as well as large families, though the last are becoming increasingly rare (Ermisch, 1990). The concept of sustainability is also coming to be applied to housing, involving such elements as selection and efficient use of resources, including land and the materials used and the day-to-day functioning of dwellings as well as other buildings; efficient use of energy; reduction and/or proper treatment of waste; health, in the broadest sense, of the occupants; and affordability (UN-ECE, 1992).

Safety in housing involves not only the standards of safety to be respected in its construction, but also in its use, for example with regard to electrical and gas installations. Above all, fire prevention is a major preoccupation, involving the ignitability and spread of flame performance of both the structure and contents of the building. Regulations have been developed in many countries, with an increasing extent of international harmonisation, relating to performance in the face of fire and other hazards and structural integrity, and since they are not discriminatory in the way that product standards may be, they are gradually replacing the latter. Such regulations apply to all classes of building, but with such public buildings as hotels, hospitals, cinemas and concert and sports halls being particularly targeted because of the greater risk to large numbers of people.

Policies to protect the health of occupants involve not only the physical internal environment of dwellings, such as the habitable area per person, ventilation, and so on, but increasingly the psychological environment. Thus, the sense of isolation that can be felt from living in a high-rise apartment block has become a powerful argument in favour of more socially acceptable forms of dwelling.

The oil price shocks of the 1970s highlighted the potential for energy conservation in better designed buildings, more energy efficient use of materials and care in the use of energy by occupants. Figure 5 (page 22) showed that in 1990 sectors other than industry and transport accounted for 35 percent of total energy consumption in western Europe. The share of energy used in the installation and operation of buildings must take up a major share of that. Furthermore, in most countries, a substantial proportion of the energy used in buildings is still being wasted, or at least could be saved through the installation of better insulation or more energy-efficient equipment. There is of course a significant capital cost involved for the owners, occupiers or users. Consequently, most progress in energy saving in construction has been made in the richer countries, notably in northern Europe, where the harsh winters add a further incentive.

While the oil price shocks stimulated interest in energy conservation in buildings, and the technology exists for high levels of energy efficiency, the weakening of energy prices in recent years has reduced the motivation for actively pursuing conservation policies. The real price of energy is likely to rise over the long term, and this prospect ought to be an incentive to governments to encourage energy saving in buildings. Furthermore, this would be in line with the principles of environmental protection and sustainability. Indeed, energy saving through better building insulation for environmental reasons may be a stronger argument than the economic one, and provides an interesting example of the interaction between policy areas.

The trend towards disengagement of public bodies, both national and local, from housing in many countries takes the form both of selling off publicly-owned dwellings to private owners or co-operatives, and of letting private construction companies take a larger stake in new building and in maintenance and improvement. There are pros and cons to this. On the positive side, it should improve the efficiency of construction activities and lower their cost, while also making them more responsive to market conditions and demand. On the other hand, it may be more difficult for governments to use the private construction sector as a counter-cyclical tool for the management of the economy, as they have tended to do in the past, for example by initiating public construction projects in a time of recession as a means of alleviating unemployment. Furthermore, it may be more difficult to control private construction activity, for instance to make enterprises respect regulations with regard to building on agricultural land or land in green belts around cities. The temptations of acquiring such land, which is generally much cheaper than land already classified as building land, can be great, and some governments and local authorities in countries with serious problems of agricultural over-production, may turn a blind eye to some farming land being converted to building, whether for housing or for commercial or industrial construction.

The problem of inner city decay has been receiving increasing attention in the more industrialised countries, especially those where extensive structural changes have been occurring, with the closure of traditional, relatively labour-intensive (“sunset”) industries and problems in attracting alternative activities. Typical examples in Europe have been regions with extensive docks and ship-building yards, steel-making or coalmining industries. A further factor has been the exorbitant cost of office space in city centres, which has caused many businesses and government departments to move to outlying areas. This move has been helped by the tremendous improvement in telecommunications in recent years. In this connection, it is quite conceivable that an increasing share of business will be conducted from the home, rather than the office, thus relieving over-charged commuting systems, especially roads.

Reverting to the inner cities, it is not easy to find ways of making them attractive, not only as places to come to work or to visit but also as places to live. Often they contain buildings, monuments and sites of cultural and historical importance, which attract tourists, but to develop them just for tourism and leisure purposes alone would be a partial solution. The problem of the inner cities, coupled with that of managing the development of the urban-rural interface in an environmentally as well as socially acceptable way, which in some respects are two sides of the same coin, appears to be among the major challenges for European policy makers in the coming years.

The scale, nature and urgency of the problems, which European policy makers are facing in the construction sector, vary considerably from country to country, much depending on population densities and living standards and the degree of industrialisation. For the countries with economies in transition, the problems are related mainly to the dilapidated state of buildings of all types, but especially dwellings, and the lack of finance and appropriate institutions to renovate or replace them (UN-ECE, 1991e, f and 1993c). An essential requirement is therefore to build up their capacity to undertake the work required, including conditions in which foreign investors will bring in not only finance but modern construction technology and management methods. To some extent, the same situation applies to other less economically developed countries in Europe, including some of those bordering the Mediterranean, although they mostly have the necessary institutions (banks, insurance, etc.) and market mechanisms already in place.

One policy direction likely to be followed by most European countries in the foreseeable future is to direct an increasing share of available construction expenditure to the repair, maintenance, renovation, modernisation or extension of the existing stock, at the expense of new building. This trend has been evident in many countries already for the past decade or more, but seems likely to be still further accentuated in the future. This is not to imply either that the share of construction in total GDP will change significantly or that total expenditure on construction will increase or decrease. Evidence for the possible long-term trends of these has not emerged during the preparation of this study. One other fairly general trend is likely to be to strengthen policy instruments to promote the adaptation of some part of the dwelling stock, together with some new building, to the changing demographic structures and to the needs of special groups of people. Probably, this will mean some decline in the average size of dwelling units, in terms of number of rooms though not necessarily in average living space per person.

Forest resource, forestry and wood supply

At first glance, policy issues in the construction sector would appear to have implications for forestry and

wood supply mainly through their impact on demand for forest products, which is discussed later. A

number of issues, which may or may not be relevant, can be raised here, however.

One concerns the possible extent of forest land lost to urbanisation and infrastructure. Most of the rural land that is built on comes from agriculture; much of that is in the more accessible areas and close to urban areas and therefore more important from the agricultural production point of view than land in more remote areas. At the moment, agriculture can, from a strictly practical point of view, afford to have some land withdrawn from production, because of over-production in many countries. Should that situation change for one reason or another, some forest land might once again come under pressure from alternative uses, either for agriculture or building. Frankly, this does not seem a likely scenario in the foreseeable future; indeed some countries have legislation that ensures the maintenance of the forest area: Switzerland, for example, requires that if some forest land has to be converted to another use, this has to be compensated for by afforestation elsewhere.

Where forest may be under most threat is in green belt areas around cities where there can be strong pressures for its transfer to use for construction, even if theoretically it is protected for social and environmental reasons. A further threat comes from the demand for secondary or holiday homes, hotels, campsites, etc., as has happened in many coastal and mountain areas, which may involve either the removal of forest cover or, if it is kept, withdrawal of the land from wood production. This has been a trend for many years and it can be expected to continue, with some impact on the forest's wood producing function.

Countering this trend is the creation or expansion of forests in or near cities for environmental and social reasons, as well as of urban forests. Creation of parks is seen as one way of improving the attractiveness of urban areas, even the inner cities, while the planting of “social” or “community” forests near cities is intended to meet the growing demand for areas in which to relax and pursue leisure and recreation activities as well as to assist in cleansing of the air from dust and pollutants. Wood production in such forests would, at best, be a secondary function.

Wood-processing industries

The cyclical fluctuations in the construction sector, and its use as a counter-cyclical tool, have a marked

impact on the wood-processing industries that are particularly dependent on the sector as a market for

their products, notably sawmilling and the wood-based panels industries. Two scenarios could be

envisaged: one in which these cyclical fluctuations continue much as before; another in which

governments become more adept at fine-tuning the use of counter-cyclical measures, such as changes

in interest rates and the timing of publicly-financed construction projects, with the result that economic

cycles, especially in the construction sector, become less marked. The present deep recession in most

west European countries is a consequence of the policies in the late 1980s/early 1990s to counter over-heating

of the economies. Now (1993/94), the pendulum has swung the other way, and policies are

being directed to the problem of unemployment, which is particularly acute in the construction sector.

The smaller forest industries, especially sawmills, may be vulnerable to recessions because they are heavily reliant on construction for their markets and because their financial structure makes it difficult for them to survive during such periods. Consequently, the long-term process of rationalisation of the sector is accelerated by recessions, with increased numbers of mills going out of production, either temporarily or permanently. In a strictly economic sense, this may be a normal and logical process, but it may be less easy to justify from other points of view, notably that of unemployment and maintaining the rural social fabric - small forest industries provide a significant number of rural jobs and can fill market niches less accessible to larger companies. Fewer sawmills, even if this does not result in a fall in total capacity, can mean reduced ability to reach all segments of the market and hence a net decline in the use of forest products.

The upstream impact of severe cyclical fluctuations in the construction market may be to complicate and make more costly the forest management process by making it more difficult to plan a regular flow of wood raw material to industry, including final cuts and thinnings, and of income.

International trade in forest products

The impact of cyclical fluctuations in the construction sector on some forest industries, discussed above,

can be even more marked on those in exporting countries, partly because changes in stock-holding in

exporting and importing countries can exaggerate the shifts in supply and demand, but also because

home-based industries in importing countries may be at an advantage to meet hand-to-mouth orders.

The impact of restrictions imposed by national or local building authorities on the use of particular materials was discussed in Section 2.8 in connection with the trade in tropical hardwoods. This, together with the voluntary exclusion of the use of certain species by architects and other specifiers in some countries for environmental or sustainability reasons, has been leading to substitution by other wood or non-wood materials. Nonetheless, as a major consumer of certain categories of imported forest products, developments in the construction industry in Europe may have a noticeable impact on the pattern and volume of Europe's trade in these products.

Markets and demand for forest products

Estimates of the use of forest products in construction are available for only a few countries. In ETTS IV

(UN-ECE/FAO, 1986), countries' end-use estimates of the “mechanical” wood products were

presented. The following shares used by the construction sector of total consumption of each product are

only approximate averages for Europe:

| - sawn softwood | 70 percent |

| - sawn hardwood | 30 percent |

| - plywood | 47 percent |

| - particle board | 40 percent |

| - fibreboard | 64 percent |

The shares differ considerably from country to country. This is especially the case for particle board: 72 percent in Finland; 5 percent in Italy.