It should be recalled that what we are looking at here are significant potential changes in policy direction. Policies already in place are having impacts on the FFI sector which can be observed and, to a certain extent, measured and internalised in the projection models for supply and demand for wood and its products. In nautical terms, this would be a “steady-as-she-goes” scenario. This, incidentally, is not the same thing as a “laissez-faire” scenario, which implies a certain benign neglect in policy making with no particular direction being provided. The extent to which changes in policy may have an impact on the FFI sector varies considerably, as indicated in the “scale and direction of impact” column of tables 8 A…J.

Table 8-A: POSSIBLE IMPACTS ON THE FFI SECTOR OF CHANGES IN POLICY DIRECTION

| POLICY AREA A: DEMOGRAPHY AND SOCIAL AFFAIRS | POLICY AREA A: DEMOGRAPHY AND SOCIAL AFFAIRS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Policy objective | Policy instrument/linkage | Impact on the forest and forest industries sector (particularly on the supply and demand of wood) | Scale of impact1 on: | Timescale2 | |

| SUPPLY | DEMAND | ||||

1. Mitigate impact of slowdown in population growth on society and economy | Improvements to welfare services and family support, housing conditions, education facilities, etc. | 1 (a) Minor improvement in demand for forest products | ** | M | |

2. Mitigate impact of population ageing on society and economy | Changes to welfare contribution systems, to retirement, and to structure of housing market, etc. | 2 (a) Minor improvement in demand for forest products | * | M | |

3. Maintain (or improve) the level of social security (health, pensions, etc.) | Changes to welfare contribution and payment systems; control management costs | 3 (a) Tighter financial regime for forestry and forest industry enterprises | * | M | |

4. Adjust housing supply to changes in household structures | More new or converted accommodation for single people and small families, older age groups, etc. | 4 (a) Improved demand for structural forest products and furniture | *** | S | |

5. Alleviate unemployment; improve labour supply/demand balance | Changes to unemployment benefits, investment for job creation, training and redeployment, alleviate social costs (to enterprise) employing lesser skilled workers, incentives for early retirement, etc. | 5 (a) Increased investment and labour availability for forestry and forest industries | ** | S | |

(b) Better possibilities to use resource and capacities | * | S | |||

(c) Costs of mobilising wood supply eased by alleviating social costs and taking in hand environmental charges | *** | S | |||

6. Restrict international migration | Tighter immigration control, more overseas investment | 6 (a) Increased investment and retention of labour in FFI sector in transition countries (CITS) with forest reserves | * | M | |

7. Slow down internal migration (rural to urban) | More investment for rural jobs, infrastructure, and direct support for farming and other rural activities

(tourism, etc.), at least to avoid further degradation of situation More investment in public works for managing landscape, protecting and monitoring the environment, managing sensitive ecosystems | 7 (a) Increased investment and labour availability for FFI sector in rural areas | ** | S | |

(b) Increased afforestation and other forestry activities | * | S | |||

(c) Increased wood supply and processing by forest industries | * | M | |||

(d) Increased wood demand for housing, hotels, infrastructure, etc. | ** | S | |||

8. Reallocate available funds for rural development to priority (from social point of view) areas | Changes in allocation of subsidies, grants, etc. in line with shifts in social welfare priorities, relief of unemployment, etc. | 8 (a) Investment in FFI sector slightly diminished | * | S | |

1 On a scale of* (= little impact) to *****(=very significant impact). This is intended to show the possible extent of impact on wood supply and demand should policy be changed from its present direction.

2 This column is intended to show how soon after a policy change has been initiated an impact might begin to take effect: S = Within 5 years; M = Within 15 years; L = Not before 15 years.

Table 8-B: POSSIBLE IMPACTS ON THE FFI SECTOR OF CHANGES IN POLICY DIRECTION POLICY-AREA B: ECONOMY

| Policy area B: economy | POLICE AREA B: ECONOMY | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Policy objective | Policy instrument/linkage | Impact on the forest and forest industries sector (particularly on the supply and demand of wood) | Scale of impact1 on: | Timescale2 | |

| SUPPLY | DEMAND | ||||

1. Economic integration - Alternative 1: Accelerate pace of international integration | Application of EEA and Maastricht agreements; entry of some EFTA countries and CITs in EC (European Union - EU - as from 1 November 1993) | 1 (a) Greater international flow of investment into FFI sector | *** | M | |

(b) Greater competition, keener prices, improved demand for forest products

(FPs) | **** | *** | M | ||

(c) Increased international trade, both intra-European and interregional, in forest products | ***** | ** | M | ||

(d) Greater harmonisation and standardisation leading to better use of forest products | ** | M | |||

2. Economic integration - Alternative 2: slow down pace of

international integration | Some EFTA countries do not to join EEA; some EC following generally successful outcome of applicant EFTA countries and CITs do not become members of EC | 2 (a) No longer applicable, generally speaking, GATT Uruguay Round negotiations | -- | -- | |

(b) However, some risk remains of protectionism in certain markets | ** | ** | M | ||

3. Improve living standards (esp, in CITs) | Measures to raise real wages, welfare services, etc. | 3 (a) Increased demand for FPs through housing, etc. in CIT | **** | S | |

(b) Changes in international division of labour and trading patterns in favour of exports of FPs by CITs | ** | M | |||

4. Improve macro-economic infrastructure (esp. in CITs) | Measures to modernise transport, telecommunications, banking insurance, other institutional and commercial services | 4 (a) Improved trading and marketing climate for FPs | ** | M | |

5. Smooth out economic cycles (less boom and bust; hence smaller swings in unemployment and inflation) | Refinement (fine-tuning) of fiscal and monetary instruments to more stable economic growth demand for FPs | 5 (a) More confident cllimate for construction, resulting in more stable and continuing regular | *** | M | |

6. Put greater emphasis on quality of life (as distinct from material gain) | Development of policy instruments more sensitive to quality of life indicators (environment, education, health, culture, crime, etc.) | 6 (a) Greater demand for forests as greenbelts, landscaping, recreation, etc., resulting in some lowering of wood availability | ** | M | |

(b) Greater demand for aesthetic and decorative use of FPs | * | L | |||

7. Put greater emphasis on sustainable development | Grater use of regulatory and economic instruments to promote economic and environmental sustainability in all sectors of the economy | 7 (a) Changes in silvicultural practices leading to some reduction in yields and wood supply | *** | M | |

(b) More emphasis on use of renewable resources leads to increased consumption of wood and its products as raw material and for energy | **** | L | |||

(c) Reduced waste and more recycling leads to slower demand growth for wood as raw material, faster growth for wood and waste paper for energy | *** | **** | M | ||

1 On a scale of * (=little impact) to ***** (very significant impact). This is intended to show the possible extent of impact on wood supply and demand should policy be changed form its present direction

2 This column is intended to show how soon after a policy change has been initiated an impact might begin to take effect: S = Within 5 years; M = Within 15 years; L = Not before 15 years.

Table 8-C POSSIBLE IMPACTS ON THE FFI SECTOR OF CHANGES IN POLICY DIRECTION - POLICY AREA C: ENERGY

| POLICY AREA C: ENERGY | POLICY AREA C: ENERGY | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Policy objective | Policy instrument/linkage | Impact on the forest and forest industries sector (particularly on the supply and demand of wood) | Scale of impact1 on: | Timescale2 | |

| SUPPLY | DEMAND | ||||

1. Diversify of energy sources (away from fossil fuels and towards alternatives | Taxes on use of fossil fuels; subsidies and grants for research and development alternative fuels | 1 (a) Increased afforestation as energy plantations | *** | M | |

(b) Increased harvesting of thinnings, small-sized and low quality wood, incl. forest and logging residues, for as energy | **** | S | |||

(c) Increased use of urban waste, notably waste paper, for heat and power | *** | S | |||

(d) Increased use of industry and post-consumption residues for heat and power | ** | S | |||

(e) Development of wood-based liquid and gas fuels for transport and other uses | ** | L | |||

(f) Fuller integration of electricity generated by wood-processing industries into national grids | * | M | |||

2. Raise energy self-sufficiency and security | Subsidies and grants for R&D and use of domestically available energy resources | 2 (a) As 1 above, esp. (a), (b), and (c) | **** | **** | M |

(b) Develop wood use for local (community, institution, hospital, farm, military, etc.)heat and power generation | ** | M | |||

3. Improve energy conservation | Subsidies and grants for research, development and use of energy-saving technology, equipment, buildings, etc. | 3 (a) Increased demand and production of sawnwood as low energy cost product | ** | ** | M |

(b) Greater use of wood-based products, esp. sawnwood, for insulation of buildings | ** | M | |||

(c) As 1, esp. (c) and (d), and 2 above | **** | M | |||

(d) Improvements in energy productivity in forest operations and industries | *** | M | |||

(e) Improvements in distribution systems of wood raw material and FPs from reduced transport costs | * | M | |||

4. Reduce environmental damage from energy production and use | Taxes on polluting and wasteful energy producers and consumers and subsidies and grants for R and D, and use of “clean” technologies; legislation to control polluting practices in energy production and use | 4 (a) More energy-efficient and “clean” energy-using technology installed in forest industries | *** | M | |

(b) Fossil fuels gradually replaced by “clean” sources of energy, including wood, in forest industries | ** | M | |||

5. Slow down/halt rise in greenhouse gas emissions from energy production and use | Carbon taxes or similar; subsidies and grants for research, development and use of techologies reducing carbon and other emissions; subsidies and grants to develop carbon sinks | 5 (a) As 1, esp. (a)-(e), 2,3(c) above | **** | L | |

(b) More forests allowed to grow to old age as carbon sinks | ** | L | |||

(c) Longevity of wood use increased through preservation, etc. | * | L | |||

1 On a scale of * (= little impact) to ***** (= very significant impact). This is intended to show the possible extent of impact on supply and demand should policy be changed from its present direction.

2 This column is intended to show how soon after a policy change has been initiated an impact might begin to take effect: S = Within 5 years; M = Within 15 years; L = Not before 15 years.

Table 8-D POSSIBLE IMPACTS ON THE FFI SECTOR OF CHANGES IN POLICY DIRECTION-POLICY AREA D: ENVIRONMENT

| POLICY AREA D: ENVIRONMENT | POLICY AREA D: ENVIRONMENT | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Policy objective | Policy instrument/linkage | Impact on the forest and forest industries sector (particularly on the supply and demand of wood) | Scale of impact1 on: | Timescale2 | |

| SUPPLY | DEMAND | ||||

1. Reduce/eliminate pollution of the environment | Adherence to international conventions; use of regulations, taxes, penalties relating to emissions of pollutants; of subsidies and grants for R&D and introduction of pollution-reducing technology and practices; and of subsidies and grants to alleviate impact of pollution on ecosystems, human health,etc | 1 (a) Health of forests in heavily polluted areas gradually restored | *** | L | |

(b) Restoration of heavily damaged forests with greater mixture of species, notably broadleaves | ** | L | |||

(c) Spread of pollution-abatement equipment in forest industries gradually to all countries | ** | L | |||

(d) Costs of pollution abatement reflected in prices of FPs: some impact on demand | ** | M | |||

2. Strengthen preservation/ conservation of natural habitats, bio-diversity, etc. | Legislation to establish protected areas, nature reserves, etc., to maintain biological and genetic diversity, and to protect rare and threatened flora and fauna | 2. (a) Substantial areas of forests transferred from wood production to protection or “semi-natural” forest in many countries: lower wood availability | ***** | M | |

(b) Stricter environmental controls on forest operations, e.g. chemicals use: reduced wood availability | *** | S | |||

3. Increase protection of game animals (animal rights) | Regulations to restrict the activities of hunters (reduce hunting quotas, increase the area forbidden for hunting, shorten the hunting season) | 3 (a) Increased damage to stands, esp, regeneration, with impact on increment and availability | ** | L | |

4. Integrate environmental policies more closely with those for other sectors | Introduce environmental impact assessments into all types of planning; establish more systematic consultation with the public and NGOs, and closer collaboration between ministries and government agencies | 4. (a) Influence on development of FFI sector in areas subject to environmental impact assessment, esp. largescale operations, such as afforestation schemes, clearfelling,“greenfield” industry installations, etc. Additional costs passed on to FP consumers: some impact on supply and demand | *** | ** | L |

(b) FFI managers have to take public opinion and external decisions on environmental concerns increasingly into account | ** | L | |||

(c) Multiple use forestry brings some loss in wood supply, even while latter usually remains main source of income | *** | M | |||

5. Strengthen policies to reduce waste and increase recovery and recycling | Introduce legislation to reduce production of waste, incl. low-waste technology; and to promote the “5 Rs principle” on waste management; subsidies and grants for R&D and increased recovery, recycling and reuse of waste | 5 (a) Significant changes in type and location of wood-processing industry to allow greater use of waste paper and wood residues | **** | M | |

(b) Lower demand for primary wood raw material, esp, lower qualities, as a result of residue and waste recycling | *** | S | |||

(c) Lower demand for certain FPs, esp, packaging materials | **** | S | |||

6. Apply principles of sustainable development | Provide guidelines, supported by legislation, in all areas of activity for achieving sustainable development in both the economic and ecological sense | 6 (a) Changes in forest management and silviculture, e.g. towards greater use of indigenous and broadleaved species and less use of chemicals, with consequent fall in average increment, longer rotations, and probability of reduced quantity but higher quality of wood | *** | L | |

(b) Improved raw material and energy input/product output ratios by forest industries | *** | ** | L | ||

(c) Trend towards production and use of longer- lasting FPs, resulting in lower volume but higher unit value of output | * | * | L | ||

(d) More diversified supply and change in public attitudes towards wood as a renewable material raises demand | ** | L | |||

(e) Change in forest management to an economically, socially and environmentally sustainable basis reduces dependence on wood as main source of income; some reduction in wood supply | * | M | |||

1 On a scale of * (= little impact) to *****(= very significant impact). This is intended to show the possible extent of impact on wood supply and demand should policy be changed from its present direction.

2 This column is intended to show how soon after a policy change has been initiated an impact might begin to take effect: S = Within 5 years; M = Within 15 years; L = Not before 15 years.

| POLICY AREA E: LAND USE, RURAL AND REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT | POLICY AREA E: LAND USE, RURAL AND REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Policy objective | Policy instrument/linkage | Impact on the forest and forest industries sector (particularly on the supply and demand of wood) | Scale of impact1 on: | Timescale2 | |

| SUPPLY | DEMAND | ||||

1. Strengthen integrated approach to land-use planning and management | Coordination of activities by ministries and other national agencies, regional and local authorities, NGOs and others involved in planning and management; public participation, incl. farmers, industries, etc. | 1 (a) Better political support for forestry and forest industry development within agreed integrated planning, but some loss of autonomy in decision-making | ** | L | |

(b) Transfer of some area of productive forest to other uses; more multiple use with wood production playing a reduced role | ** | M | |||

2. Provide space for urban and peri-urban development, incl. infrastructure | §Integrated planning procedures for reallocation of rural land to other uses, investment in roads and other infrastructure | 2 (a) Greater use of forests near conglomerations for non-wood functions; creation of new forests near cities for recreation, etc. | * | L | |

(b) Reduction of some costs as infrastructure improves | * | M | |||

3. Provide better living conditions, employment and standards of living, esp. in rural areas

| Strengthen regional development support to rural areas through grants, subsidies, tax concessions for expanded or new rural activities, e.g. tourism, artisans, etc. | 3 (a) Stimulus to forestry, incl. afforestation, only some of which for wood production | **** | L | |

(b) Increase in downstream activities, incl. harvesting and transport, small and medium forest industries, artisans, etc. in rural areas | *** | ** | M | ||

(c) Increase in wood demand for construction and renovation in rural areas, incl. hotels, other tourist facilities | ** | M | |||

4. Ensure better protection of rural environment, landscape and amenities | Legislation, loans, grants and subsidies for activities to protect and enhance aesthetic and cultural quality of rural areas | 4 (a) Stricter controls on forestry activities, incl. harvesting, with some reduction in wood production | *** | M | |

(b) Transfer of some productive forest to protected areas (see E.2(a) and 4; reduced wood availability | **** | M | |||

5. Ensure better equilibrium between the different uses and user interests of the countryside | Establish mechanisms (consultation, enquiries, etc.) for reconciling conflicts of interests, public participation | 5 (a) See E.1 to 4 above, esp. 1(a), 2(a), 4(b) | ** | L | |

| Regional policies | |||||

6. Improve the equilibrium between the economic development of different regions | Targeting of government development support to less favoured regions and specific economic sectors (see 1 above) | 6 (a) Enhancement of the economic value of forests | * | M | |

(b) Enhancement of the touristic value of forest areas | * | L | |||

7. Improve the rural and ecological capital value of specific zones | As 4 above | 7 (a) Public sector financing of landscape and environmental management of wooded areas relieves cost pressures on wood production | *** | L | |

| Rural policies | |||||

8. Ensure optimum use of rural land through improved planning procedures, multiple use, etc. | Legislation, loans, grants and subsidies for intensifying rural land use, esp. in densely populated areas and near urban conglomerations | 8 (a) Greater emphasis on multiple use forests, esp. in densely populated areas; wood production reduced to secondary priority | ** | L | |

(b) See E.1–4 above concerning forestry within land use planning | *** | L | |||

9. Introduce sustainable development concepts and goals in land-use planning and management at all levels | Legislation, based on UNCED Agenda 21 and other international agreements and national policies | 9 (a) Changes in silvicultural and other forestry practices, choice of species, rotation age, use of chemicals, etc. with impact on quantity and quality of wood supply (see also D.6(a)) | **** | L | |

1 On a scale of * (= little impact) to ***** (= very significant impact). This is intended to show the possible extent of impact on wood supply and demand should policy be changed from its present direction.

2 This column is intended to show how soon after a policy change has been initiated an impact might begin to take effect: S = Within 5 years; M = Within 15 years; L = Not before 15 years.

| POLICY AREA F: AGRICULTURE | POLICY AREA F: AGRICULTURE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Policy objective | Policy instrument/linkage | Impact on the forest and forest industries sector (particularly on the supply and demand of wood) | Scale of impact1 on: | Timescale2 | |

| SUPPLY | DEMAND | ||||

1. Reduce government support for food production, incl. shift to forms of direct support

| Reduction of price guarantees, subsidies for fertilisers, grants and loans for equipment, buildings, certain activities, to increase self-dependency in farming. Abandonment of considerable areas of marginal agricultural land; Support (less than before) for alternative uses of the land “Set-aside” schemes for agricultural land. Assistance through training, grants etc. for alternative employment to farming for food production,early retirement | 1 (a) Natural regeneration of abandoned agric. land, resulting in forest or other wooded land, generally of low wood productivity but often valuable from social and environmental points of view | *** | L | |

(b) Afforestation of agricultural land for: | |||||

1. Primarily social or environmental purposes, with wood production a secondary objective

| **** | L | |||

2. Primarily for production of industrial wood raw material

| **** | ||||

3. Energy plantations (see also C.1(a)) | *** | M | |||

4. Creating carbon sink (see also C.5) | *** | L | |||

2. Reduce government support for agricultural exports and protection of domestic markets from imports | Export subidies reduced or eliminated on certain commodities Barriers to trade reduced or eliminated | 2 (a) Stimulus for expanding production of forest products, either for export (partial replacement of food exports in trade balance) or for import substitution | ** | S | |

3. Target assistance more to farmers in remote or disadvantaged regions (mountains, etc.) | Direct support in form of subsidies and grants for activities and services other than food production (tourism, environmental protection, etc.) | 3 (a) As F.1(b) above | **** | ** | L |

4. Reduce negative impact on the environment of agricultural practices, e.g. intensive farming, chemicals; | Reduction or removal of subsidies and grants for chemicals or practices that harm environment; taxation on chemicals; legislation for same objective | 4 (a) 1st alternative: If impact leads to increased abandonment of agricultural land, result as in F.1 above | **** | L | |

(b) 2nd alternative: If impact is to increase extensive agricultural methods, incl. natural (organic) farming, slower or even zero increase in availability of agric. Land for alternative uses | ** | L | |||

(c) Increase in agro-forestry | ** | L | |||

5. Ensure sustainable development of agriculture | Legislation and fiscal measures to encourage adoption of economically and environmentally sustainable practices | 5 (a) See B.7, D.6 and F.4 above | *** | L | |

6. Extend privatisation of agriculture in CITs | Legislation and financial assistance for the purchasing and management of formerly publiclyowned farms, incl. necessary infrastructure | 6 (a) Afforestation a significant alternative use for agric. land abandoned partly as a result of privatisation and change to market economy in CITs; see F.1, 2 and 4 above | **** | L | |

7. Promote alternative uses (than food production) for marginal agricultural land and set-aside

| Subsidies and grants for R&D, introduction of alternative crops or uses, including processing | 7 (a) See F.1(b) above. Afforestation one of several options for alternative use (than food production) of agric. land | **** | L | |

(b) Stimulus for expanding industries to process wood from existing or newly created forest resources | *** | M | |||

(c) Stimulus for establishing wood and other biomass-using heat and power generating plants | **** | S | |||

1 On a scale of * (= little impact) to ***** (= very significant impact). This is intended to show the possible extent of impact on wood supply and demand should policy be changed from its present direction.

2 This column is intended to show how soon after a policy change has been initiated an impact might begin to take effect: S = Within 5 years; M = Within 15 years; L = Not before 15 years.

| POLICY AREA G: INDUSTRY | POLICY AREA G: INDUSTRY | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Policy objective | Policy instrument/linkage | Impact on the forest and forest industries sector (particularly on the supply and demand of wood) | Scale of impact1 on: | Timescale2 | |

| SUPPLY | DEMAND | ||||

1. Adapt national legislation in response to increasing “globalisation” of industry | Develop or adapt legislation affecting the behaviour of multinational companies in individual countries | 1 (a) Economic integration leads to further concentration of wood-processing industries: | |||

1. trend towards globalisation of large scale industries and their affiliates; | *** | M | |||

2. “niches” for small and medium-scale industries based either on location vis-à-vis raw material or markets or their product specialisation | *** | M | |||

2. Promote conditions for fair trading and competition | Develop or strengthen legislation relating to monopoly trading, cartels, price-fixing, etc Strengthen international cooperation through GATT, EC, etc., to allow fair trading competition at international level | 2 (a) Policies for more open competition lead to lower prices, increased demand, resulting in: | |||

1. Alternative 1: increased market opportunities for efficient domestic industries with likelihood of greater self-sufficiency in

FPs; | *** | *** | S | ||

2. Alternative 2: increased international competition and trade with greater import penetration and some weaker FP industries going out of business | *** | ** | S | ||

3. Strengthen enforcement of legislation relating to patents and protection of non- patented information | Strengthen measures to protect property and intellectual rights and to encourage the transfer of technological information in a “proper” way | 3 (a) More rapid dissemination of technological know-how and crossborder investment in technology, improved efficiency in wood industries and competitivity against other materials | ** | ** | M |

4. Use of industrial development as a tool to

combat unemployment | See A.5 above | 4 (a) As A.5 above | ** | S | |

(b) Greater availability and use of trained labour in wood industries, esp. in more labour-intensive industries and those in rural areas (e.g. saw- milling) | *** | M | |||

5. Restructure and privatise industry in CITs as major component of strategy of shift to market economy | Develop legislation to create conditions (infrastructure) for the restructuring and privatisation of industries in CITs Promotion of joint ventures and other forms of cooperation between CITs and other countries Promotion of conditions for foreign investment in industry | 5 (a) More foreign investment in wood industries in CITs, with preference for greenfield projects rather than modernisation of existing industries | **** | M | |

(b) Increased exports from above industries resulting from good competitivity (low wages, modern technology) | ** | M | |||

6. Promote location of industry in

disadvantaged areas as component of policy of regional development | See E.6 above | 6 (a) As E.6(a) above | * | M | |

(b) Sawmills and other rural-based industries benefit | ** | M | |||

(c) Increased demand for FPs resulting from expansion of industrial activities in rural areas | ** | S | |||

7. Enforce environmental protection and promote sustainable development in

industrial sector | Strengthen legislation, subsidies, loans and grants for R&D and investment in pollution control technology, greater saving of inputs (raw materials), lower greenhouse gas emissions, use of renewable resources, etc. | 7 (a) Compliance with increasingly strict environmental regulations more evenly applied across region, esp. as regards pollution emissions; lower and more uniform levels of air and water pollutant emissions from wood industries; higher costs, esp. in older industries; some closures where standards cannot be met | *** | M | |

(b) Outcome of 7(a) leads to changes in competitive positions of wood industries and in trading patterns of FPs | ** | M | |||

(c) For wood residue and waste paper recycling, see C.1(c,d), D.5 | **** | ** | M | ||

8. Promote conversion of defense industries to other functions following end of “Cold War” | Provide subsidies and grants for R&D and new investment for converting defence industries | 8 (a) Diversion of investment and resources away from defence benefits all non-defence sectors, but FFI not more than others | * | M | |

1 On a scale of * (= little impact) to ***** (= very significant impact). This is intended to show the possible extent of impact on wood supply and demand should policy be changed from its present direction.

2 This column is intended to show how soon after a policy change has been initiated an impact might begin to take effect: S = Within 5 years; M = Within 15 years; L = Not before 15 years.

Table 8-H: POSSIBLE IMPACTS ON THE FFI SECTOR OF CHANGES IN POLICY DIRECTION - POLICY AREA H: TRADE

| POLICY AREA H: TRADE | POLICY AREA H: TRADE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Policy objective | Policy instrument/linkage | Impact on the forest and forest industries sector (particularly on the supply and demand of wood) | Scale of impact1 on: | Timescale2 | |

| SUPPLY | DEMAND | ||||

1. Trade liberalisation - Alternative 1: National ratification and application of successful

outcome of GATT Uruguay Round negotiations | Progressive reduction or elimination of tariff and other trade barriers in accordance with GATT agreement Some protectionist pressures remain | 1 (a) Stimulus to world economic growth and trade, incl. demand and trade of FPs; lower prices | **** | S | |

(b) Increased competition and “survival of the fit-test”, also in FFI sector | *** | M | |||

2. Trade liberalisation - Alternative 2: Break down of GATT negotiations followed by moves towards greater protectionism, build - up of inward-looking trading blocks, etc.3 | Raising of protection trade barriers Creating new or extending existing inward-looking regional trade blocks | 2 (a) No longer relevant unless GATT accord not ratified | -- | -- | |

3. Policies to ensure environmental protection through trade measures | Quantitative restrictions or quotas on exports or imports imposed for environmental protection reasons Tariffs on imports for same reasons National, regional or local building codes or other restrictions on use of imported goods for same reasons Eco-labelling (or eco-profiling) of exports or imports to certify origin, e.g. from sustainable source Legislation on packaging to reduce volume or promote it recycling, incl. return to exporting country | 3 (a) To extent that such measures are acceptable within GATT framework, and where they directly affect FPs, reduction in demand and trade of goods from environmentally sensitive and non-sustainably managed forests in both tropical and temperate zones | **** | S | |

(b) Measures to put environmentally sensitive forests into protected areas (reserves); see D.2(a) | **** | S | |||

(c) Greater use of packaging materials that are easier to recycle or return, with varying impacts on FFI sector: | |||||

1. Alternative 1: Preference for packaging materials that are biodegradable, can be recycled or used for energy favour FPs, esp. paper and paperboard, for shipment of goods | ** | S | |||

2. Alternative 2: Measures to reduce amount of packaging used lowers demand for FPs | ** | S | |||

4. Increase in aid for development, restructuring, etc., in both CITs and developing countries

| Government and other financial and technical assistance on bi- and multilateral basis Improvement of economic climate in aid-receiving countries through tax breaks, subsidies, etc. | 4 (a) Expansion of forest industries overseas offers opportunities for investment, supply of

equipment and technical know-how, joint ventures | * | M | |

(b) Those industries meet growth in demand in overseas markets and some exports, incl. to Europe (see also G.5 above) | ** | M | |||

(c) Overseas assistance also for afforestation and reforestation | ** | L | |||

(d) Aid increasingly tied to environmental protection and sustainable forest management, with impact on volume of production and exports (see also E.2(a), 6(e)) | *** | L | |||

5. Increase in private foreign investment through take-overs, joint ventures, marketing and trade | Private foreign investment and technology transfer to enter overseas markets or for export through tax breaks Improvement of investment climate in receiving countries | 5 (a) As 4 above | ** | M | |

1 On a scale of * (= little impact) to ***** (= very significant impact). This is intended to show the possible extent of impact on wood supply and demand should policy be changed from its present direction.

2 This column is intended to show how soon after a policy change has been initiated an impact might begin to take effect: S = Within 5 years; M = Within 15 years; L = Not before 15 years.

3 Since this table was prepared, the GATT Uruguay Round negotiations were completed and, subject to ratification by the contracting parties, will become effective. Therefore, this alternative could be deleted.

| POLICY AREA I: CONSTRUCTION | POLICY AREA I: CONSTRUCTION | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Policy objective | Policy instrument/linkage | Impact on the forest and forest industries sector (particularly on the supply and demand of wood) | Scale of impact1 on: | Timescale2 | |

| SUPPLY | DEMAND | ||||

1. Shift in emphasis towards improving living conditions, incl. quality (rather than quantity) of housing | Strengthening of legislation regarding quality of construction Improvement of standards, incl. move towards

performance standards, codes of practice, building regulations Targeting of subsidies, loans and grants to specified goals Preference given to low-rise dwellings and demolition of some high-rise, esp. low quality, buildings | 1 (a) Strengthened regulations, standards, etc. may generally have neutral impact on FP consumption | * | S | |

(b) However, where product standards tended to create bias, e.g. regarding behaviour in fire, move towards performance standards beneficial | ** | S | |||

(c) More low-rise construction favours FP use | *** | M | |||

2. Greater consideration given to housing needs of specific segments of the population, e.g. aged, handicapped, single parents | Targeting of subsidies, loans and grants to specific needs Increased share of public sector construction devoted to meeting specific needs | 2 (a) Conversion of buildings slightly favours use of FPs | ** | M | |

3. Refine use of construction as a counter-cyclical economic tool (reduce unemployment, inflation pressures) to reduce “boom-and-bust” fluctuations | More finely-tuned and better timed use of monetary and fiscal measures Ditto for use of subsidies, loans and grants | 3 (a) If result would be to smooth out cycles in construction sector to some extent, more regular evolution of market helpful to long-term development of FP industries | ** | M | |

4. Greater priority for renovation, maintenance and improvement of existing housing stock | Targeting of subsidies, loans and grants for this purpose | 4 (a) Favours increased use of FPs for these uses | **** | M | |

5. Shift ownership and investment in construction more towards private sector | Sale of publicly owned housing stock Reduced role of national and local housing authorities in constructing and managing dwellings and encouragement of private enterprise | 5 (a) Change in specification and ordering towards smaller parcels | * | M | |

6. Stricter guidelines for dwellings and institutional, commercial and industrial construction for environmental protection

| Strengthening of legislation, codes of practice, standards, etc. | 6 (a) Less risk of forest land being used for building | ** | L | |

(b) FP use could be reduced if behaviour in fire, for example, continued to have a bad press | *** | S | |||

7. Greater support for sustainable development in human settlement policies, esp. energy and materials conservation, recycling of demolition waste, etc. | Targeting of subsidies, loans and grants for this purpose Legislation to spur conservation practices in construction Adaptation of codes of practice, regulations, performance standards, etc. | 7 (a) Increase in use of FPs for insulation and for its environmentally benign properties | *** | M | |

8. Greater attention to the principles guiding the allocation of land for construction | Strengthen planning procedures for transfer of agricultural and other land for building Strengthen legislation with regard to uses of greenbelt land and other sensitive areas | 8 (a) As 6(a) above | ** | L | |

9. Greater emphasis on rural development | Targeting of subsidies, loans and grants to improve living conditions in rural areas, through improved housing, tourism, infrastructure, etc. | 9 (a) Some increase in FP use for rural building projects | ** | M | |

10. Greater emphasis on inner city restoration | Targeting of subsidies, loans and grants for this purpose | 10 (a) Some use of FPs for repairs and maintenance, incl. for scaffolding and formwork | * | M | |

1 On a scale * (= little impact) to ***** (= very significant impact). This is intended to show the possible extent of impact on wood supply and demand should policy be changed from its present direction.

2 This column is intended to show how soon after a policy change has been initiated an impact might begin to take effect: S = Within 5 years; M = Within 15 years; L = Not before 15 years.

| POLICY AREA J: THE ROLE OF THE PUBLIC SECTOR | POLICY AREA J: THE ROLE OF THE PUBLIC SECTOR | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Policy objective | Policy instrument/linkage | Impact on the forest and forest industries sector (particularly on the supply and demand of wood) | Scale of impact1 on: | Timescale2 | |

| SUPPLY | DEMAND | ||||

1. Adapt legislation and institutional structures to political developments, including

decentralisation of authority | Decentralisation of national administrations with increased policy-making roles for regional and local

governments International unification or harmonisation of national policy-making, e.g. within European Union, but with increasing application of subsidiarity principle | 1 (a) Further trend towards decentralisation of forest administrations in some countries | * | L | |

(b) Move towards international coordination or harmonisation of national forest policies | * | L | |||

2. Measures to make/allow private sector accept greater responsibility for ownership and management of production and infrastructure | Privatisation of State-owned industries, utilities, etc. | 2 (a) Complete or partial privatisation of State forests and/or Forest Services in some countries, in both western Europe and CITs | ** | M | |

Privatisation of State-owned forest industries and services, in both western Europe and CITs | *** | M | |||

3. Measures to make private sector and individuals accept greater responsibility for financing social services | Changes to welfare charges and benefits (taxation, retirement, health, unemployment, etc) Reduction of subsidies and grants, e.g. for agriculture (see F. above), transport | 3 (a) FFI sector would not be affected more than other parts of the economy by such policies | * | M | |

4. Reduction of public sector deficit | See J. 2 and 3 Tighter control of public spending Increased taxation | 4 (a) FFI sector would not be affected more than other parts of the economy by policies of greater financial stringency | ** | ** | M |

5. Greater use of fiscal measures for purposes other than filling the public purse, e.g. for environmental protection incentives | Changes in taxation structure, e.g. away from income tax and towards other forms (VAT, carbon tax, etc.) | 5 (a) Some measures could benefit FPs as environmentally benign products, e.g. for power and heat generation (see also C.) | *** | *** | M |

6. Ensure acceptable foreign trade and

currency balances; more stable currency markets | Increased cooperation in financial markets, exchange rate policies, e.g. through ERM | 6 (a) More stable trading climate for FPs | *** | S | |

(b) Realignment of exchange rates, when they occurred, would nevertheless alter competitivity and pattern of international trade in FPs | *** | S | |||

(c) However, generally more stable money markets would aid overseas investment in FFI sector with view to expansion of exports or import substitution (see also H.5) | ** | M | |||

7. Use of public intervention to tackle specific problems, e.g. unemployment, retention of key industries, strengthen competitive

position, etc. | Targeting of subsidies, loans and grants for specific sectors Government support for training, extension, R&D, etc. | 7 (a) FFI sector could benefit from such policies as a relatively labour intensive and environmentally benign sector | *** | *** | M |

(b) Greater sensitivity of FFI sector to local and national public opinion could result in some reduction in wood production | ** | S | |||

1 On a scale of * (= little impact) to ***** (= very significant impact). This is intended to show the possible extent of impact on wood supply and demand should policy be changed from its present direction.

2 This column is intended to show how soon after a policy change has been initiated an impact might begin to take effect: S = Within 5 years; M = Within 15 years; L = Not before 15 years.

The impacts on the FFI sector which rated four or five pluses or minuses in tables 8 A…J are the following:

| Policy area/component | Major impacts on FFI sector |

|---|---|

| A. Demography and social affairs | None |

| B. Economy | |

| a) Accelerated economic integration increases intra-European and interregional trade in FPs | Greater competition, keener prices, improved demand for forest products (FPs) |

| b) Improved living standards in countries with economies in transition (CITs) | Increased demand for FPs in CITs |

| c) More emphasis in economic policies on sustainable development of the economy | Greater use of renewable resources, incl. wood Reduced waste, more recycling = faster growth in demand for residues and waste paper, but slower growth in demand for wood raw material |

| C. Energy | |

| d) Diversification of energy sources | Increased harvesting of thinnings, small-sized and low quality wood, residues, waste paper, etc. for energy |

| e) Raising energy self-sufficiency and security | As d) above: increased demand as well as supply of above assortments |

| f) Improving energy conservation | As d) above |

| g) Slow down rise in greenhouse gas emissions | As d) above |

| D. Environment | |

| h) Preserve/conserve natural habitats, biodiversity, etc. | Productive forest transferred to other functions (protection, etc.) Stricter environmental controls on forest operations; lower wood supply |

| i) Reduce waste; increase recycling | Lower demand for primary wood raw materials, e.g. small-sized wood; higher availability of recyclable materials, incl. waste paper Changes in type and location of wood-processing industries Lower demand for some FPs, e.g. packaging materials |

| E. Land use, rural and regional development | |

| j) Support rural areas/populations | Stimulus to forestry; however, only partly for wood production |

| k) Better protection of rural environment, landscape and amenities | Some productive forest transferred to protected forest as h) above = reduced wood availability |

| l) Sustainable development | Changes in silviculture with impact on quantity and quality of wood supply |

| F. Agriculture | |

| m) Reduced support for food production | Stimulus for afforestation for various functions, incl. wood, energy and social/environmental |

| n) Targeted assistance to farmers in remote areas | As j) above |

| o) More emphasis on environmental protection in agriculture | More land for forestry (afforestation) |

| p) Rationalisation of agriculture in CITs | Stimulus for forestry in CITs, incl. afforestation |

| q) Promotion of alternative uses to food production | Forestry one major land use option for wood for energy, industry and other uses |

| G. Industry | |

| r) Restructuring and privatisation in CITs | Foreign cooperation and investment in CITs' forestry and wood-processing industries |

| s) Sustainable development | As c) and l) above; positive and negative impacts on wood supply |

| H. Trade | |

| t) Trade liberalisation from outcome of GATT Uruguay Round negotiations | Stimulus to FFI sector, as to other sectors, = increased trade and demand for FPs |

| u) Environmental protection in trade policies | Reduction in supply, trade and demand of environmentally sensitive FPs, e.g. from old growth/ natural forests |

| I. Construction | |

| v) Renovation, maintenance | Increased use of FPs |

| J. The role of the public sector | None |

Thus, there were found to be 22 policy areas where changes in direction are having or may have a significant impact, whether positive or negative, on the FFI sector. On closer inspection, however, there is a degree of overlapping, and these 22 areas can be consolidated into seven groups of policies, as follows:

Further streamlining may be achieved by combining (1) with (2); (4) with (5); and (6) with (7). This would leave four major policy areas, as follows:

In all cases, it should be recalled that what are being considered are the actual or conceivable changes in emphasis or direction of policies from the existing ones. For instance, it can be assumed that all countries will, whatever happens, continue to pursue policies for the protection of the environment, and these will affect the FFI sector to a greater or lesser extent. What has been attempted here, however, is a preliminary assessment of which policy changes, if countries were to make them, could have impacts on the FFI sector beyond those that are likely to result from present policies. As this assessment is the subjective and personal one of the authors, it is open for further criticism, discussion and possible alteration.

The above listings are based on the cases where the impact on the FFI sector was rated at four pluses or minuses or more in the “scale and direction” column in tables 8 A…J. In addition to the high to very high impact cases listed above, there are a further forty-five cases with three pluses or minuses (moderate impact), which should not be overlooked in the analysis. The impacts of the majority of these forty-five cases fell within the four main policy areas listed above but there were enough cases that warrant adding three further headings:

Since this study is concerned primarily, although not exclusively, with the impact of policies on the supply and demand of wood and its products, the “scale an direction of impact” column in tables 8 A…J distinguishes between the impact on supply and on demand of wood and its products. In some cases they may have an impact on both, but for the most part it is fairly clear where the impact will fall. Out of 78 cases (counting those with both positive and negative impacts twice), where impacts were related at three pluses or minuses or more, 52, or two-thirds, affect the supply of wood and its products; and 26, or one-third, the demand side. There are five policy areas where the impact would be very largely on supply: D-Environment; E-Land use, rural and regional development; F-Agriculture; G-Industry; and J-The role of the public sector. For four others, the impact would be equally on supply and demand or slightly more on demand: A-Demography and social affairs; B-Economy; C-Energy; and H-Trade. The only policy area where the impact would be mostly on demand is, not surprisingly, I-Construction. The general conclusion to be drawn from this is that a majority of the policy changes considered in this study would, if they were introduced, have impacts on the supply side of the supply/demand balance.

The direction of the impact that policy changes would make, that is, whether it would be likely to result in increases or decreases in supply or in demand of wood and its products, is shown by the pluses and minuses in the “scale and direction of impact” column in tables 8 A…J.

For supply: 33 of the impacts, or nearly two thirds, out of the 52 cases of three or more pluses or minuses would result in an increase; and 19, rather more than one third, in a decrease. Some of the impacts would be both positive and negative. An example of this is where a change in policy would result in increased supply of one category of product, for example recycled waste paper, at the expense of another, for example small-sized roundwood and thinnings. Another example would be where a policy that would favour domestic industry might result in reduced imports, or vice versa.

Policy areas where the impact of changes in policy would be in most cases to increase supply are: B-Economy; C-Energy; F-Agriculture; and G-Industry. The impact in policy area D-Environment would be mainly to decrease supply.

For demand, in 21 cases out of 26, or more than four-fifths, changes in policy would be likely to provide a stimulus, and only 5 to restrain it. The policy areas with the strongest positive impact are: B-Economy; C-Energy; and I-Construction.

An attempt was also made in tables 8 A…J to indicate the timescale of the impacts of policy changes, that is to say, how long after the changes were initiated they would begin to have an effect. Three time periods were chosen: Short - within the following 5 years; Medium - within 5 to 15 years; and Long - not within the following 15 years. Thus, if decisions were taken within the next 2 to 3 years, the periods within which impacts could begin to be felt correspond roughly to the short, medium and long-term forecasting horizons in ETTS V: the years 1995–2000, 2000–2010, and, for such aspects as roundwood removals, 2010–2040, respectively. Judgement as to the timescale of impacts is, like other assessments made in the study, subjective and the proposals for S, M or L in the righthand column of the tables are presented for discussion and possible change.

Taking the same 78 cases of medium, high and very high impact of policy changes as for the scale and direction of impact, as discussed in the previous paragraphs, the breakdown into short, medium and long timescales for the impact on supply is 10 : 26 : 16. That is to say, over 80 percent of the impacts would be felt in the medium to long term, and less than 20 percent in the short term. The long-term impact is especially noticeable for policy area F-Agriculture, and this is understandable when such measures as the afforestation of abandoned agricultural land, and the time before plantations come into production, are considered. Some important short-term impacts on supply are possible in policy area D-Environment, for example the immediate reduction in wood availability that would result from the transfer of productive forest land to other use categories (nature reserves, etc.).

With regard to the timescale of impacts on the demand side, the breakdown of cases into short, medium and long is 9 : 15 : 2. All but a fairly small fraction (8 percent) could begin to have an impact within 15 years or so. In some cases, a short timescale corresponds with the lead time between the policy change and the start-up of new mills or power generating plants; in others, a change in trade policy, for example concerning trade in environmentally sensitive species, could have an almost immediate impact.

To summarise the foregoing, this analysis has identified four main areas where changes taken in policy directions would have major impacts on the FFI sector in the decade or two following their introduction. They are: policies to stimulate economic expansion; policies to stimulate efforts to find alternative sources of energy and to conserve it; policies to intensify environmental protection and promote sustainable development; and policies relating to rural and regional development, including adjustments in agriculture. To these may be added a further three: policies to improve the quality of life; policies relating to industry and trade matters other than policies primarily aimed at stimulating expansion; and policies to change the role of the public sector.

There is a degree of over-lapping between these seven policy areas, and each one could have a number of different impacts on the FFI sector, sometimes working in opposite directions. All of them include, to a greater or lesser extent, one area of general concern, namely the transition of the economies of the countries of central and eastern Europe from planned systems to forms of market economy, and in further analysis it may be convenient to treat this as a separate policy area, which in fact affects not only the countries themselves but all countries in Europe and many in other regions as well.

It is difficult to summarise in a few lines the possible major impacts on the FFI sector from the eight policy areas highlighted above. The following is therefore intended to be indicative, rather than comprehensive:

Economic expansion. A distinction has to be made between short-term policies, e.g. to pull economies out of recession, and the longer-term ones which are of primary concern in this study. The latter would have the effect of stimulating a continuing growth in demand for forest products, notably in the construction sector, and thereby growth in production, including investment in new capacity, and trade. The impact would take effect in the short-to-medium term after the introduction of new policies.

Energy. Wood as a fuel would stand to gain considerably from policies to seek alternative energy sources (to fossil fuels) and to reduce the harmful impact on the environment (including climate change) of burning fossil fuels, provided the environmentally benign nature of wood (including waste paper) for fuel was satisfactorily demonstrated, which should not be difficult. This would open up major markets for assortments of wood and residues that may otherwise be difficult to use, notably small-sized wood. The impact of policy changes would be felt in the short-to-medium term, as well as in the longer term as a result of the establishment of energy plantations. If appropriate policies were adopted, afforestation for fixing CO2 could become an important role for forestry, with implications also for increased wood availability in the long term.

Environmental protection and sustainable development. Policies in this area would mainly work towards reducing the volume of wood supply. Some would have an impact in the short term, such as the transfer of productive forest land to other categories, e.g. nature reserves, or the reduction in supply and export availability from old growth forests. Changes in silviculture to put forests on a sustainably managed basis would reduce availability in volume terms, but might raise the quality of output in the longer term. Waste management would reduce demand for certain forest products (packaging), but might stimulate the recycling of waste paper and wood residues. This would augment the supply of these assortments, but partly at the expense of primary wood raw material, with consequent problems for silviculture (see 2. above).

Rural and regional development, including agriculture. Various inter-related policies in this area would generally offer considerable opportunities for the FFI sector, including scope for the expansion of wood supply in the medium to long term. Forestry, notably with non-wood benefits as objectives (landscape, amenities, recreation and tourism, nature conservation, etc.), could be called upon to play an increasingly important role in maintaining the social and economic viability of rural areas, and would become a more significant component in the integrated land use planning and management of these areas.

Quality of life. Greater emphasis on values other than, or at least additional to, material gain could have the effect of reducing growth over the long term in consumption of goods, including forest products; of giving more weight to durability and aesthetic values; and of putting greater emphasis on environmental standards. In other words the emphasis would be on sustainable development in the economic, social and environmental meanings of the term (see 3. above). Forestry for purposes other than wood production would be an important beneficiary. Given that wood, when produced in a sustainably managed way, is an environmentally benign and renewable material, opportunities would also exist for it to replace other materials in certain end-uses.

Industry and trade matters. The globalisation of industries and markets and increasing international competition, and the reaction of governments to these trends, will have a significant impact on the FFI sector, as on all others over the medium to long term. Because of their relatively large scale, the pulp and paper industries are part of the globalisation process, the other wood-processing industries (sawmilling, wood-based panels, etc.) much less so. However, the latter may even gain some benefit to the extent that they can develop product and market niches and improve the quality of their products and services. Much will depend on their being willing and able to amount effective co-operative promotion and marketing efforts, backed by more intensive R&D.

The role of the public sector. There are contrasting trends: one is towards disengagement and decentralisation of the public sector, leading to less State involvement in the ownership and management of resources, the means of production and services - in other words, privatisation; the other is towards more policies that direct activities towards national objectives, notably in such fields as environmental protection and sustainability. Forestry stands to gain, especially from the second trend, provided its benefits to society in those respects can be clearly demonstrated. Public support for forestry will, however, be more for its role in providing non-wood benefits than wood.

Countries with economies in transition (CITs). Policies to effect the transition to pluralistic societies and forms of market economy are already in place. The question is whether there will be further marked changes in the direction of those policies that would affect the FFI sector. As it is, aspects of all the seven preceding points are relevant to the CITs. A key issue is how long it will take to establish the political, institutional and economic infrastructure in these countries needed to attract the massive amount of foreign investment required for the mobilisation of their resources and industries. There is considerable potential for the development of the FFI sectors in the CITs, and strong latent demand for forest products waiting to be fed when conditions are right. The impact would be felt in various ways by the FFI sector throughout Europe.

Michael Porter, Professor at Harvard Business School and specialist in industrial strategies, has shown from observation of developments during the 1980s (The Competitive Advantage, published in 1985) that to understand the development of a sector in the medium to long term (and to reduce the economic impact on its probable profitability) it is necessary to analyse not only the competitive interactions that exist between the actors directly involved in the sector (the industries), but also the relations and the forces which are or may be exercised on the direct actors in the sector by the following partners and contexts:

the customers:enterprises, traders, end-users, etc.;

the suppliers: of raw materials, intermediate products and services, etc.;

the new enterprises which are able or which wish to enter the sector; this requires the barriers to entry, whether economic or regulatory, to the sector to be identified;

the new technologies, products and processes which could replace those currently in use by enterprises;

the institutional context, the legislation, and policies that could modify the rules governing the functioning of the market. (Initially, this aspect was barely taken into account by Professor Porter who felt that, in an open market context, regulations would have little influence).

This analytical method, the Porter model, rapidly became one of the main reference methods for carrying out strategic analyses of enterprises. It was widely used in numerous fields, also by Professor Porter himself in 1992 to analyse the competitive situation of certain States and Countries (Strategic Choices and Competition: Technical Analysis of Sectors and Competition in Industry, Economia, Paris).

It should be stressed that the Porter model is not a scientific instrument for precise forecasting, but rather an analytical tool and an aid to decision making. It is, in effect, for the decision makers to assess the relative weight to be given to the various elements identified in the analysis and to draw their own conclusion.

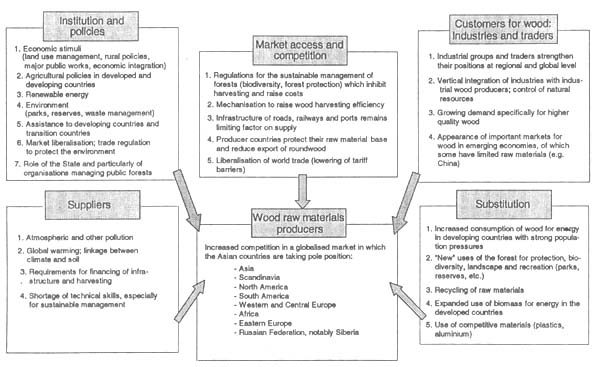

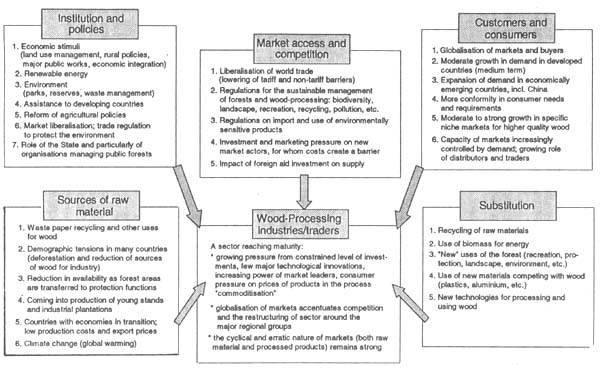

This methodology will be used in a more modest way in the present study to present the forest and forest industries sector in a highly condensed manner. Charts B and C present the industrial processors of wood and the wood raw material producers, respectively, and place them in the context of their relations with their economic and institutional partners and the pressures which the latter exert on them.

Thus, to summarise the elements for a strategy for 10 to 15 years ahead for wood-processing industries at the centre of the exercise, Chart B shows in particular that:

the wood-processing industries are in a situation of strong competition which is leading to a restructuring of the sector around major regional or international groups;

the customers and consumers are going to play an increasingly important role and exert strong pressure on the industries: globalisation of markets, standardisation of requirements, strengthening of trading positions and distribution systems. At the same time, specific demand for certain higher quality wood products, the appearance of newly emerging economies as important consumers of processed products (for example, China), may offer opportunities to industries;

suppliers of raw materials are adapting their trading relations with industries which will need to adapt to new constraints: waste paper recycling, reduced availability from forests transferred to protection functions, export of low-priced wood from certain countries, in the longer term perhaps a reduction (or increase) in availabilities as a result of global warming;

new materials (notably plastics and aluminium) are replacing wood in construction, “new” uses of the forest (recreation, protection, etc.) are taking over from its traditional function of producing wood;

the access of new actors to the wood-processing sector is on the one hand being helped by the liberalisation of world trade but on the other hand being braked by the new import regulations intended to protect the environment;

lastly, institutional and political developments in the FFI sector (the principal purpose of the present study) are going to play a determining role on the evolution of relations between the various actors.

To conclude the commentary on Chart B, it may be said that:

the wood-processing industries, faced by numerous pressures on their activities, are certainly going to face even greater difficulties to obtain a reasonable return on their investments, because they will not be in a position of strength vis-à-vis their competitors or their partners or in the economic and policy context;

the future of the sector is going to depend principally on the external institutional and policy choices rather than on the socio-economic factors which the industries themselves can control or influence.

Chart C, in which the producers of wood raw material are placed at the centre, does not need as much commentary as Chart B. The principal lesson that can be drawn from it may be summarised as follows:

wood producers are more and more dominated by and subjected to forces that are stronger than themselves: industries that are becoming increasingly concentrated, local populations that are cutting down the forest (in developing countries), green movements that are seeking to have protective legislation imposed, urban populations which give preference to the “other”, i.e. non-wood, functions of the forest (landscape, recreation, protection).

Only in the case of higher quality wood, a relative shortage, which may be provoked by the growing demand from emerging economy countries, and the development of the use of biomass for energy, may offer favourable opportunities for producers.

The question remains, however, whether they would be able to benefit economically, even in these cases, given their weakened capacity to take advantage of their potential?

Thus for wood producers, even more than for the wood-processing industries, it will be the institutional and policy decisions that will condition their future situation.

In short, the study does give credence to the supposition on which it is based, namely that it is the policy choices outside the FFI sector, notably as regards energy, the environment, stimuli to the economy, and international economic relations, that will condition the forces affecting the FFI sector. On the other hand, the directly involved actors in the sector, such as the owners of forests and forest industries, will have rather limited margins of manoeuvre and their policy choices will not be decisive for the sector.

These have been indications of areas where major developments could occur if certain policy directions were taken. Whether those directions will be followed is altogether another question. Even though there is increasing convergence of policy-making within Europe, particularly within the framework of the European Communities (European Union), national policies will continue to differ to a greater or lesser extent according to the particular situation of each country. Nevertheless, policies in one country are being increasingly influenced and guided by what is going on elsewhere, and a certain degree of convergence in policy-making can be assumed. Whether the critical mass of political will exists that is needed to inaugurate some or all of the policy changes discussed in this study is, however, an open question. This should be borne in mind when considering the proposal for a base scenario below, which is not, repeat not, offered as a forecast, but merely as a basis for discussion and something with which to compare alternative scenarios, whether national or European, which readers may put forward.

Chart B: Development of relations with the wood-processing industries part of the FFI sector

Chart C: Development of relations with the wood-producers part of the FFI sector