Indonesia is an archipelagic country situated between the continents of Asia and Australia. The equator runs in the middle of it. Rainfall ranges between 700 and 5,000 mm per year, averaging 2,190 mm per year. The mean temperature is 27°C. 2

The Indonesian land surface amounts to ± 2 million Km˛ , 70 percent of which is forest land. The population was reported in 1981 to be 147.4 million, which means an average density of 77 people per Km˛ . Java, with 7 percent of the total Indonesian area, is the most populous region with an average population density of 690 per Km˛ .

Owing to various factors dating back from past times, about 20 percent of the Indonesian land surface is now unproductive and is comprised of areas of scrub, alangalang, and barren land. Half of it, i.e., about 20 million ha, is already in extremely bad condition and is commonly called critical land. In these areas, erosion is serious as are problems of floods, aridity, silting of water reservoirs, and other environmental disturbances.

Rehabilitation of degraded watersheds has been carried out since 1969 but in the last 8 years it has been done intensively and on a large scale. This paper will give a brief account of the Indonesian watershed management programme with emphasis on its institutional aspects.

Critical Lands

As a result of misuse and mistreatment of land, vast expanses of critical land can now be found in almost every province. A watershed area is considered critical if it shows the following conditions:

i) It has large areas of serious erosion.

ii) The results of erosion, i.e., floods, siltation, etc. have threatened the fruits of development (infrastructure, industry, agriculture, etc.) in the watershed areas concerned.

Based on the results of the surveys of 75 watersheds by the Directorate General of Forestry (1974-1980), critical land amounts to 8.5 million ha. of which about 60 percent is agricultural land.

Causes of Degradation

Technically, the main causes of watershed degradation are first, land use in excess of the land capability, and second, land treatments which disregard soil conservation principles.

Frequently practised traditional farming methods detrimental to the soil are:

i) Shifting cultivation, which is farming by way of forest clearing, burning, extensive planting without any efforts to conserve the soil, which will afterwards be abandoned by the cultivators who move elsewhere to repeat the same practices.

ii) Uncontrolled grazing, resulting in overgrazing, which brings about erosion.

The population growth demands increasing areas of land for agriculture. This population pressure has become hard to control in almost all provinces. The mountainous upper reaches, which are hydrologically dangerous, have been the targets of shifting cultivation and (uncontrolled) grazing. There are at present an estimated I million families of shifting cultivators adding about 400,000 ha of soil degradation per year.

National Awareness

Land and water are natural resources that affect the life and livelihood of the nation, the more so for Indonesia being an agrarian country with the greater part of its population depending on agriculture for support. Therefore, people must be made increasingly aware of the importance of sustaining land and water resources.

The degraded situation of watersheds has been considered a national problem, not just a problem of the farmers themselves. This appears from the measures, legal arrangements and development programmes the government has carried out.

It takes a long time to foster such an awareness. Half measures in the field of information which are not pursued in a consistent way often give unsatisfactory results. Since 1961 national campaigns, named National Greening Weeks, have been launched during the third week of every month of December. The campaigns involve all levels of society in programmes of mass tree-planting, exhibitions/visualization, information and extension in various media.

Watershed rehabilitation is a time- and fund-consuming undertaking. So, continuity in the implementation of the programme need be guaranteed. For this purpose it is deemed necessary to have a stable government policy, which is to be formulated further into a long-range programme.

National Policy

The watershed management programme is a development programme which has been given priority by the government. It is included in the 1983 GBHN (Basic National Policy), :which, among other things, reads:

"The rehabilitation of degraded natural resources of forest, land and water needs stepped-up escalation through integrated watershed and regional approach.

In this context the Forest, Land and Water Preservation Programme need be continued and improved even further."

The Basic National Policy is a long-term development policy every government in power should adhere to. It is a decision of the NPR (National People's Assembly) in its 5-yearly sessions for the election of the President and Vice-President, and for the establishment of the Basic National Policy. Being the Assembly's mandatary, the President is duty-bound to implement all provisions of the Basic National Policy.

Legislation

Indonesia has a number of laws related to matters relating watershed management, i.e., i) Agrarian Act No. 104/1960, ii) Forestry Act No. 5/1967, and iii) irrigation Act No. 4/1982.

At this juncture the Ministry of Forests is drafting a Soil Conservation Bill, which upon ratification into an Act will be the legal basis for watershed management.

Concept

Watershed management is, in the broader sense, an undertaking to maintain the equilibrium between elements of the natural ecosystem of vegetation, land and water on the one hand and man's activities in utilizing the elements on the other hand.

Degradation of any one of these elements will have its influence on the other elements and will, in the end, result in the degradation of watersheds.

The treatment technique of rehabilitating degraded watersheds is in fact a soil conservation treatment, be it tree planting or building structures for erosion control (terraces, checkdams, etc.). In selecting appropriate techniques or systems, the intended purpose and expected outputs should be clearly stated, then approaches should be considered for preparing the watershed management programme.

Fifteen years' experience in watershed management in Indonesia has shown the great importance of a firm formulation of the above mentioned matters, which is the basis for determining the treatment technique in the field. Only after the ups-and-downs of implementation over the last five years have we developed solid footing in these matters.

Aims of the Watershed Management Programme

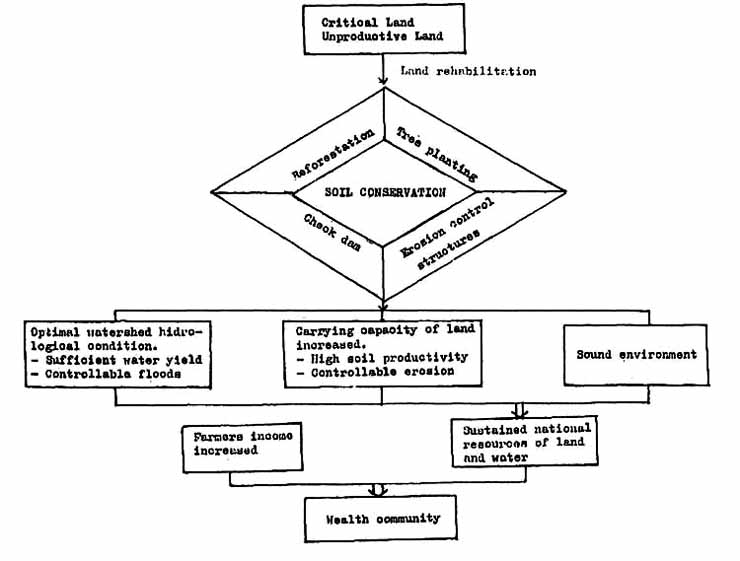

Watershed rehabilitation is aimed at achieving the following objectives (Chart 1):

i) An optimal watershed hydrological condition, which means the availability of water in sufficient quantities and quality, and controllable floods.

ii) An increased carrying-capacity of the soil, characterized by high soil productivity and controllable erosion.

iii) A safe and pleasant environment.

Following the achievement of these three objectives, the next aim is the realization of sustained (usefulness of) natural resources of land and water, and an increase in income for the farmer and the community in general.

The watershed approach is to be taken because firstly watersheds are hydrological units that catch, store and release water through networks of streams into the main rivers, which will finally end in their estuaries by the sea, and secondly, watersheds are also ecosystems of vegetation, land and water with their mutually interacting elements.

Land Rehabilitation Pattern

Watershed rehabilitation is land rehabilitation with soil conservation as its core. The

selection of an effective soil conservation technology that fits a certain region is not

an easy job. We are faced not only with technical matters but also with socialeconomic and

traditional concerns and with the level of the farmers, skill and knowledge.

Taking into account terrain conditions, the land rehabilitation pattern for a watershed is

described in Table 1.

As a means of enlightenment, 10-ha demonstration plots are established within villages. The plots are used to demonstrate various techniques of structures for erosion control, proper land use and productive planting methods.

Table 1. Land rehabilitation according to terrain.

| Terrain Condition | Treatment Technique |

| (1) State-owned forest area; | (1) Reforestation |

| (2) Community forests that are neglected or that are in such a condition as to be unfavorable/dangerous for agriculture; | (2) Tree planting, 400 - 1,500 trees per ha |

| (3) cultivated private land on (extremely) sloping ground; | (3) Construction of structures for erosion control: terraces, waterways, gully plugs, grass barriers, etc. |

| (4) High erosion-intensity sloping areas | (4) Checkdams |

Implementation

The programme that deals with watershed rehabilitation began in 1969 and is called the Programme for the Preservation of Forest, Land and Water. Its activities under the Soil Conservation Programme are steadily expanded to cover 21 provinces, 164 districts and 11,000 villages. During the last five years the annual budget averaged US$ 100-125 million allocated to 250 projects.,

The main activity of the programme is reforestation of forest lands, while other activities which are carried out outside forest lands are classified as regreening. The accomplishments of the programme between 1979 and 1983 are listed in Table 2.

Table 2. Accomplishments of the Programme for the Presentation of Forest, Land and Water Between 1979 and 1983.

| Forest Land | |

| Reforestation | 800,000 ha |

| Farmer's land (regreening) | |

| Tree planting Village forests Demonstration plots Terracing Waterways Checkdams |

1,873,388 ha 272,517 ha 2,753 units 375,774 ha equivalent 184,576 ha equivalent 2,388 units |

General Considerations

In the institutional development of watershed management attention should be paid to the underlying problems mentioned hereunder.

Integrated character of watershed management

The watershed management programme involves a lot of agencies such as Forestry, Agriculture, Livestock, Environment, Public Works, Local Government Agencies, etc. each in its own jurisdiction and scope of responsibility. The problem now is how to establish effective coordination and synchronization among them.

Structure of the government administration

In a direct or indirect way, watershed management requires involvement of every level of the government administration (the Ministry of Home Affairs). Special attention should be paid to the village-level structure of the government administration and social organizations.

A solution should be found to avoid negative effects of the bureaucratic mechanism on the operation of the project. On the village level it is necessary to devise a mechanism which will be instrumental in inducing farmer and community participation in all project activities.

Project scale

The organization is structured to support the operational activities. The bigger the volume of activities, the more complex the organizational structure will be. Now the question is how to keep effective functioning of supervision and control. Appendix 1 illustrates the volume of activities in Indonesia.

Organization

Functional pattern

The administration of watershed management is arranged according to the functions as

indicated in Table 3.

Table 3. Administrative functions for watershed management in Indonesia.

| Administrative functions | Institutions |

| (1) Policy making, budgeting authority at national level | - Central Government, i.e., 7 Ministries |

| (2) General management, financial arrangement, control on provincial level. | - Provincial government |

| (3) Planning and extension | - Watershed Planning Agencies under the Ministry of Forests |

| (4) Programme implementation | - Reforestation Project - Regreening Project |

| (5) Training | - Forestry Training Centres |

| (6) Research and development | - Forest and agricultural research institutes - Watershed Management Development Centre |

Structure

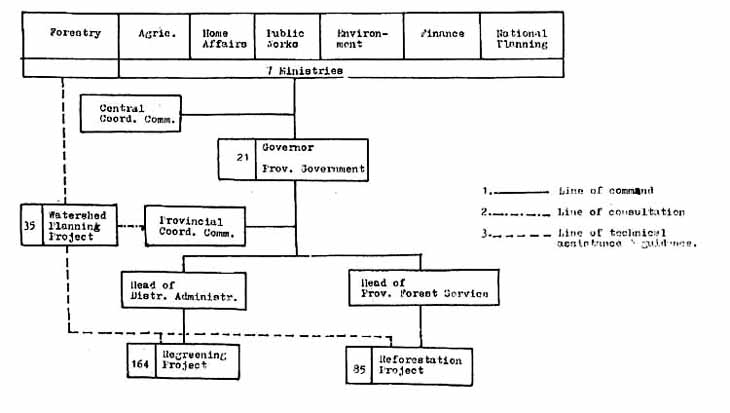

Presidential Decree No. 9/1983 set forth the organizational structure of the Programme of the Preservation of Forest, Land and Water (Chart 2).

Central Government

The Ministers of Forests, Agriculture, Home Affairs, Public Works, Finance, and the National Bureau of Planning, are responsible for the programme. In discharging their tasks the Ministers are assisted by a Central Coordinating Committee (CCC) with the main functions of:

i) Establishing a broad national policy

ii) Determining the annual budgets and work plans

iii) Establishing procedures and regulations

iv) Exercising general control over the programme

v) Giving guidance to the Provincial Administration

The membership of the CCC consists of officials of echelons I and Il of the seven

Ministries. The committee has the purpose of maintaining harmony in policy making and

measures taken by the seven Ministers on watershed management.

Having the functional authority over watershed management, the Ministry of Forests has a

special Directorate General of Reforestation and Land Rehabilitation which includes:

i) The Directorate of Reforestation

ii) The Directorate of Soil Conservation

iii) The Directorate of Regreening and Shifting Cultivation Control

iv) The Watershed Management Development Centre

At this time Soil Conservation Services are being formed on 35 watersheds.

Provincial Government

The Provincial governments, in this case the governors, are responsible for the implementation of the programme in their respective province s as regards:

i) Financial arrangements of the budget that has been determined by the central government;

ii) Supervision and reporting on budgetary expenses by the Projects.

iii) Development, safeguarding and maintaining the results of regreening and reforestation

To carry out the above functions the Governor is assisted by a Provincial Coordinating Committee (PCC). The PCC has a position and duties similar to those of the CCC but at the Provincial level. It is also aimed at achieving harmony of both policy and steps taken by the agencies related to provincial-level watershed management.

District Heads are responsible for regreening carried out by the Regreening Project within their respective Districts. Furthermore, they give guidance to the public in order that the people share a sense of responsibility for the safeguarding and maintenance of the regreening and reforestation results.

Chart 2. Organizational chart of program for preservation of forest land and water.

Regreening Projects

The working area of the Regreening Projects corresponds with the administrative territories of the Districts concerned. The head of the agriculture or forestry service of the District becomes the project manager, who is responsible concerned to the district head.

Field activities are targeted for tree planting, terracing, construction of waterways, checkdams, etc., on the farmer's land but they also serve to extend information and provide technical enlightenment. The average annual volume of activities for each Regreening Project is described in Table 4.

| Budget Area of land rehabilitation Number of villages Number of extension workers |

US$ 283,000 3,720 hectare 71 35 |

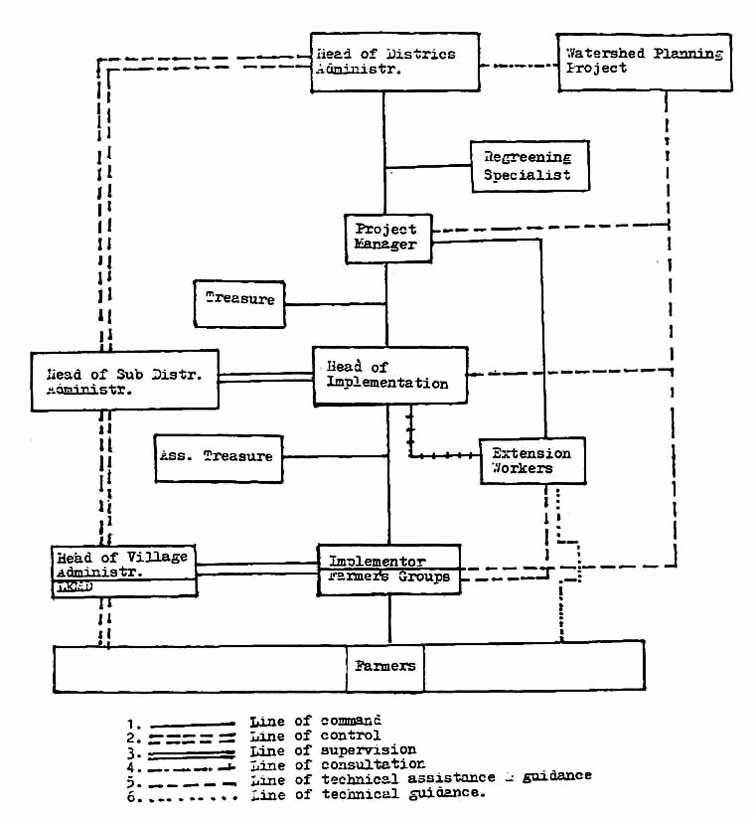

The functional pattern of the Regreening Project is as follows (Chart 3):

i) Responsible Official District Head, assisted by a regreening specialist.

ii) Project Manager Head of the District Agriculture or Forest Service

iii) Head of Implementation Head of the Subdistrict Agriculture office

iv) Implementor Farmers group

v) Controlling function Subdistrict Head and Village Heads

vi) Technical assistance and guidance Watershed Planning Project

The farmers form groups of 20-40 people. Each group is led by a key-farmer, who serves as a contact person of the Project through the extension workers. Instructions, distribution of materials, incentives are given to the farmers through the said keyfarmer. At regular times the key-farmers hold meetings at the local Agricultural Extension Centre and discuss problems arising from the regreening activities. Extension is given intensively through demonstration plots, which are model farms of 10 ha per unit.

On the village level, farmer groups are coordinated by Lembaga Ketahanan Masyarakat Desa (LKMD), a social organization for self reliance.

Reforestation Projects

Reforestation Projects are implemented by the Forest Districts, the working area of which

have no identical boundaries with the Government Administration. The Projects are

subordinated to the Provincial Forest Service. Concerning organizational structure,

mechanism and work procedure, the Projects have no problem al all as they follow the

established state of affairs of the Forest Service.

Chart 3. Organizational chart of regreening project.

Planning

Some Requirements

Watershed rehabilitation projects need to have firm, stable plans because of their

long-term nature, large expenditure of funds, and the necessity of involvement of the

farmers, who make up the major part of society. In selecting a suitable rehabilitation

technology, three aspects must be taken into account and be fully met, namely;

i) It should have an appropriate technical design to control erosion and streamflow regime in an effective way,

ii) It should be socio-economically sound in order that the undertaking will directly increase the farmers' income,

iii) it should motivate the farmers' sense of responsibility and participation in the implementation of the programme.

Every system or technique of soil conservation considered for introduction should first be tested to find out whether it meets the above three criteria. For this aim, experienced and highly capable designers are required.

Planning System

In line with the nature of watershed management, the planning process should adhere to the following system:

i) The watershed area is a planning unit. The reason is the fact that a watershed is an ecosystem area of vegetation, land and water. Evaluation of the results of management are facilitated because a watershed is a household of water resources which catches and releases water.

ii) integrated watershed management planning is in principle a soil conservation programme but in the broader sense. The vegetational or civil engineering techniques involve activities with aspects of forestry, agriculture, animal husbandry, hydrology, etc., combined in an area. The soil conservation programme will achieve optimal results only by integration of all these activities in accordance with locality, time and a well balanced volume (program).

iii) Synchronization with other development programmes on the same watershed is essential. In Indonesia, the watershed management programme is regarded as -a subsystem of the watershed development programme. This is justifiable indeed, since other development programmes such as on food crops, animal husbandry, cash crops, etc. have reciprocal bearing on the watershed programme. Though synchronization is ideal, it is difficult to carry out as each sector has its own policy and planning. of 35 watersheds only three can now be synchronized into the watershed development programme.

Institution of Planning

At the initial stages when the volume of the field programme was still limited, the implementing agencies could do the planning themselves.

In 1977 when the Program began to grow ± 900,000 ha per year), it was deemed necessary

to set up the Watershed Planning Agency (P3RP-DAS) to carry out planning activities. Its

working area covers one or several watersheds. There are 35 units of P3RP-DAS in

Indonesia, each unit making plans for an average of 25,000 ha/year.

The P3RP-DAS have the main function of carrying out field surveys, preparing 5-year and

annual plans, evaluating the results of the programme, giving guidance to Regreening

Projects, and carrying out information and extension activities.

Planning Mechanism

i) The Central Coordinating Committee gives national directives on the work volume for the coming fiscal year based on the estimated budget to be received for further allocation (in outline) to each watershed.

ii) Based on the above directives the P3RP-DAS makes field surveys and carries out landsurveying and mapping. These plans may differ from the above mentioned directives in accordance to the prevailing field requirements and conditions.

iii) The results of planning are brought up for consultation with the village, the Subdistrict and the District. After being amended according to need, they are conveyed to the Provincial Government, i.e., the Provincial Planning Bureau for approval.

iv) The plans are then submitted to the Ministry of Forests and the CCC for approval and legalization.

The Central Government approval is given in conjunction with the legalization of the related year's budget.

The mechanism as stated above, namely coming from top to bottom and from bottom to top is not always running well. Consultation with the various levels of Provincial Administration are not always successful as it may happen that not enough attention is shown in this matter. The application of the principle of "bottom-up" planning still needs improvements. it is the more difficult at the village level, because the farmers' organization, the LKMD, has not yet functioned very well.

Problems

The main problems in watershed management planning are:

i) The limited availability of basic data needed such as maps of the required scale, data on soil, land-use, water yield, rain intensity, etc.

ii) Lack of personnel to make (field) designs of soil conservation treatments.

iii) Inadequate participation by agencies at the village level up to the Provincial level in the planning process.

In the past five years efforts have been stepped up to improve the planning process. Studies and surveys have been made in a more systematic and intensive way, personnel training has been intensified and continued information has been extended to the public.

Funding Mechanism

Budgeting system

Funds for watershed management are categorized into the development budget, not into the routine budget. Budget allocations are arranged according to the kind of development programme and further specification into the respective projects. The watershed management programme is part of the programme for the Preservation of Forest, Land and Water and has 250 units of projects.

With this budgeting system, coordination within the programme, which has a crosssectoral nature, can work well. Only at the implementation stages are the departments engaged each in their own functions.

The watershed management programme uses a centralized budgeting system for planning and a decentralized system for implementation.

Funding mechanism

i) One year before the fiscal year, the Ministry of Forests submits to the CCC its needed national budget in accordance with the prepared physical (field) plan, which is based on standard unit costs for each kind of activity.

ii) After evaluation and the necessary amendments, the CCC passes the budget proposal to the National Planning Bureau and the Ministry of Finance.

iii) After approval/ratification by Parliament, the seven Ministers issue a joint decision on the allocation of funds to the Provincial Governments, specified according to existing projects in their provinces.

iv) Based on the joint decision, project managers make out operational plans containing specifications of time schedules for physical activities and financial outlay. operational plans require legalization (approval) by the Governor concerned.

v) Farmers receive their subsidy (incentives) in accordance with the realized field works through the local government's bank.

Incentive Scheme

The activities in the framework of watershed management are carried out on critical land belonging to the state (reforestation), to farmers or to private companies. Reforestation is entirely financed by the state, activities on farmer's land are subsidized (incentives), whereas private companies are to bear the full burden of activities on their land.

Some Principles in Providing incentives

i) Incentives are given to farmers owing to the extra work they do, such as terracing, tree planting, etc., in addition to their daily farm work. They generally lead a poor existence, so need subsidies or incentives even more.

ii) Incentives should necessarily be given in the right way to stimulate farmers to do the work properly. For this purpose it is important to determine which part of the work should be paid for, which incentives are attractive (not always with money), and what is the right time for distributing them, that is when farmers are in need of them.

iii) Incentives can be given 100 percent of the required spending if the work is in the public interest and not directly in the interest of individual farmers. An example would be the costs of constructing checkdams and waterways.

iv) In general, incentives are given according to the value of the prices of materials and tools needed plus modest living costs. Workers' wages are for the most part born by the farmers.

Tariff of Incentives in Indonesia

The incentives given are worth 21 to 100 percent of the actual cost. Table 5 gives the tariff of incentives in force in Indonesia.

| Actual cost | Incentive | |||

| Kind of Work | Unit | (Rp'000) | (Rp'000) | Percent |

| 1. Community forest 2. Tree planting 3. Model farms 4. Terracing 5. Waterways 6. Checkdam |

ha ha 10 ha ha ha unit |

120 95 7,783 240 110 30,000 |

70 20 4,500 124.5 65 30,000 |

58 21 58 52 59 100 |

Rp 980, = US $1

Summary and Discussion

General problems

The previous discussion attempted to give a picture of various institutional aspects of watershed management programmes in Indonesia by way of examples or experiences. Of course, differences may be found if these experiences are compared with other countries which have different conditions. Greatly influencing conditions and situations are among other things, government policies, legislation, the situation of the farmers and society and the physical conditions of watersheds.

Nevertheless, from a watershed management point of view, we are faced with the same general problems, mainly problems pertaining to coordination, centralization vs. decentralization, control, and people's participation. Of interest is the report (May, 1983) prepared by a watershed assessment team set up by the Government of Indonesia and USAID, which paid particular attention to institutional aspects.

Coordination

It has been suggested that watershed management programmes have an integrated or crosssectional character. To achieve optimum results, effective coordination is absolutely required. For this purpose, Indonesia takes the following:

i) The centralized budgeting system has a budget allocation arranged according to the development programme, not according to the Ministries.

ii) One plan is developed for one watershed as the "One river one plan" issue in Indonesia.

Coordination must be established on all levels from Central government to village levels. This is difficult, but it should be done continuously. This has largely been achieved in Indonesia. However, numerous shortcomings are still felt and there are constraints to progress in certain Provinces.

Centralization vs. Decentralization

The problem of centralization vs. decentralization will always arise in many organizational arrangements. As a matter of course, it depends on government policy and the organizational structure of government administration. Both centralization and decentralization have positive and negative aspects. For example, in Indonesia the basic organization has always been changing. Prior to 1976 it was full centralization and after that decentralization in implementation whereas planning and budgeting remain centralized. Decentralization demands well-balanced capabilities from local government apparatus. This condition has always been a drawback to decentralization.

Control

Watershed rehabilitation comprises field activities on scattered locations, often with inaccessible terrain conditions. A great variety of work should be done in line with the terrain conditions.

For the smooth and orderly course of progress it is necessary to have an effective control system and an orderly monitoring system. First, the apparatus should be set up and, for its operation, fiscal performance standards are needed. These requirements are becoming more important as in proportion to the size of the project.

Experience in Indonesia indicates that improvements can be made in the effectiveness of control.

People's participation

To achieve maximal results, farmers and the public in rural areas should take part in the process of planning, implementation and control. Although this principle is hard to practice, it should persistently be pursued. This is very important as in this way the farmers will have a sense of responsibility and are stimulated to accomplish the programme as well as possible.

It often happens that the constraints are to be found within the governments or project apparatus themselves. The bureaucratic mechanism is prone to give orders rather than to listen and in the meantime the farmers are not well organized. The villages in Indonesia have LKMD's which are the villagers' forums of deliberation on all problems concerning the development of their villages. However, the LKMD's have not yet been able to function sufficiently. The issue of "bottom-up" planning is still hard to implement, though some progress seems to have been made.