Training, research, demonstration and technology packages constitute important areas of action for a successful watershed management (WSM) programme. This paper reviews the current status of training and education in WSM worldwide and concludes that both these are either nonexistent or grossly inadequate in the developing countries of Asia, Pacific, Africa and Latin America with a few exceptions (e.g., China, India, Indonesia, Philippines, Thailand, Jamaica and Venezuela). Among the developed countries USA, UK, Australia, New Zealand, France and Japan have a large number of colleges and universities which offer courses and training opportunities in watershed sciences.

It is recognized that for a successful implementation of WSM programmes there is need for well trained, well oriented and committed supervisory, middle level and field level staff. To achieve this goal there is need for professional orientation, refresher and trainers-training programmes. The roles and responsibilities of the user institution, the training institute and the trainees for the successful outcome of these training programmes are identified.

It is concluded that even though training opportunities are inadequate and costly, they are not effectively utilized. The diversion of trained personnel from set programmes, inappropriate training, and paradoxically too many training opportunities under some circumstances all contribute to this situation.

Critical deficiencies in research also exist. With the exception of China, India, Indonesia, Philippines, East Africa, Zimbabwe, Nigeria, Brazil and Venezuela, research facilities are either nonexistent or grossly inadequate. The research needed is problem solving or applied research with an appropriate mix of basic research. Since research is expensive, it is essential that the relevance of research be critically scrutinized. Organization of research in developing countries can follow three courses of action namely i) research conducted elsewhere with a possibility of its adaptation; ii) previously conducted research in the country (reported/not reported) and iii) research to be initiated in response to the need of development programmes.

The results of research need to be expressed in practical ways through demonstration or pilot projects to promote WSM programmes.

Presently, most governments of developing countries have varying degrees of concern about the sustainability of land-water-plant systems, watershed degradation and rehabilitation. Consequently, and subject to the availability of resources, some are willing to invest in and undertake programmes related to soil and water conservation, afforestation and flood control, in addition to and apart from programmes of food production and agricultural development. In addition to the resources invested by governments themselves, large amounts of funds are provided as aid and as soft loans by international aid agencies (e.g., UNDP, FAD, UNEP, etc.), bilateral aid agencies (e.g., SATA, CIDA, USAID, Australia, New Zealand, etc.), banking institutions (IBRD, ADB, etc.) and nongovernment organizations.

International aid/loan assistance received by various countries or given by different international agencies has been reviewed by FAD for the Asia Pacific Region up to 1982 (FAD, 1982). Information about nationally and internationally supported programmes for watershed management can be easily compiled for review.

A successful watershed management programme comprises five areas of action to be implemented and coordinated:

i) Policy and legislation

ii) organization to implement and extend

iii) Research, demonstration and technology package

iv) Availability of trained personnel

v) Peoples participation

The parties of successful watershed management and other rural development programmes are political leaders, central planning ministries, policy and decision makers in the concerned ministry(ies) at federal and state levels, government implementing department(s) at federal and state levels, project director(s), project staff and the intended beneficiaries. Except for intended beneficiaries and project staff, the rest of the participants fall in the category of policy/decision makers and senior supervisors. This paper focuses on these parties.

This overview document deals with training, research and demonstration and attempts to summarize the accured knowledge worldwide.

Watershed Management - a Technology

Watershed management integrates a wide variety of sciences and disciplines including soil science, agronomy, forestry, engineering, hydrology and agrostology. In other words the practice of watershed management is a technology just as plant protection and seed production are technologies. In fact, since watershed management deals not only with biophysical aspects but also with alternate land uses -- which affect the lives of people -- it has to consider many socio-economic interactions. To that extent people who practice watershed management have to be not only competent in the biophysical sciences, but they also have to be sensitive to the needs, aspirations, and responses of the people who are affected and hopefully benefited by such management.

For planning, managing, implementing and evaluating watershed management programmes, person power is needed. Then the question arises --when do we get these persons trained? Watershed management, as a technology, is not widely taught all over the world. It is taught by a few institutions in the developed world and more recently by a few countries of the Asia-Pacific region. It is certainly not taught in many colleges and universities around the world.

Present Status of Training in Watershed Management

FAO (1982) recently evaluated the present status of education and in-service (or on the-job) training in many countries of the AsiaPacific region (Table 1). Apart from China, India, Indonesia, Philippines, and Thailand, all other countries of the Asia-Pacific region have unsatisfactory to very unsatisfactory conditions of ensuring availability of trained person power for watershed management programmes. The same is true of developing countries in Africa and Latin America.

1 Training includes "on-the-job" and formal teaching aimed at imparting technical, economic and social skills and insights needed by a person to perform a job well as per the job requirements. This paper focuses primarily on "on-the-job" training -- mostly short term and nonformal.

Table 1. Present status of education and training in watershed management in Asia-Pacific.

Present Status of* |

|||

| Country | University Education | Vocational Training | In service Training |

| Pakistan | 5 | 3 | 5 |

| India | 4 | 3 | 2 |

| Nepal | 5 | 4 | 5 |

| Bhutan | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Bangladesh | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| China | 4 | 3 | 2 |

| Burma | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| Thailand | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| Lao | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Sri Lanka | 5 | 4 | 4 |

| Indonesia | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Philippines | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Fiji | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Tonga | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| W. Samoa | 5 | 5 | 5 |

* Present status is evaluated as: 1 = Excellent; 2 = Good; 3 = Fair; 4 = Unsatisfactory and 5 = Very Unsatisfactory.

Even in the case of countries which have good conditions for training and availability of person power there is need for expanding and strengthening these facilities. We can take India as an example.

It is noteworthy that India in its very first Five Year Plan (1951-56) not only included soil and water conservation programmes but also simultaneously provided for training (Tejwani, 1979a). India trained 1366 supervisors and 4438 middle level technicians up to September 1984 in regular courses, each of 51 months duration conducted at the Central Soil and Water Conservation Research and Training Institute. In addition, it trained a large number of supervisors and middle level technicians in short courses on watershed management and soil and water conservation (489 by September, 1984). Inspite of this massive effort, the person power trained has not been sufficient to meet the needs of expanding development programmes which has been a major constraint in starting/ implementing/reaping better fruits from soil and water conservation and watershed management programmes (Vohra, 1974; Tejwani, 1979b). If this is true of India, one can be certain that it is much more true of the other countries. However, it should be clearly recorded that even though training is not the only component needed for the success of watershed management programmes, no watershed management programme can be expected to succeed if it is to be implemented by untrained and unoriented people. Thus, any for ward looking country sensitive enough to invest in watershed management programmes should simultaneously invest in educating and training personnel.

Teaching the technology of watershed management is at a critical state; only Thailand, Indonesia and Philippines have a satisfactory situation. As soil and water conservation and watershed management programmes are attracting greater attention and offer more opportunities for employment, it is time that colleges and universities in the developing countries establish courses which contribute to implementation of watershed management programmes.

Levels and Types of Training

Levels of training

Watershed management programmes, like any development programme, pass through certain phases of management namely:

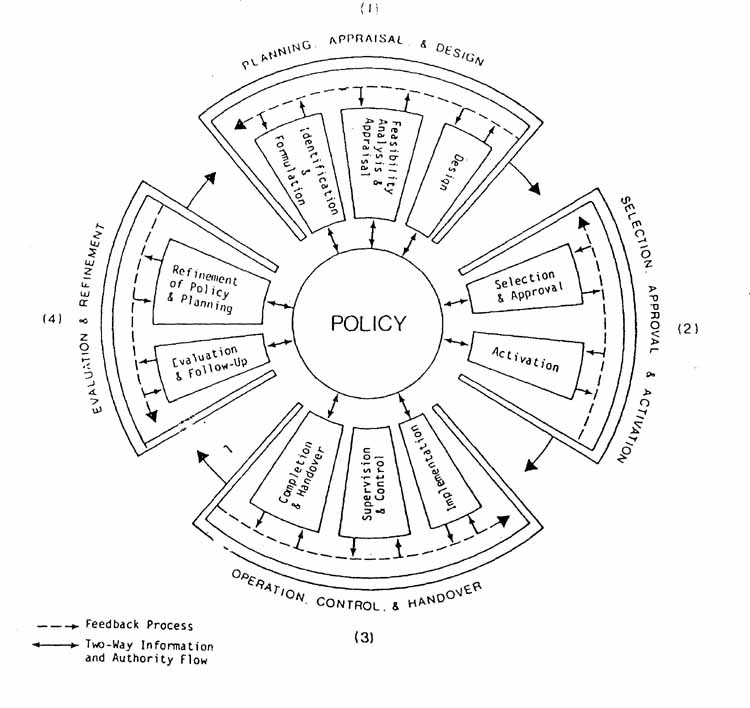

i) planning, appraisal and design,

ii) selection, approval and activation,

iii) operation, control and handover, and

iv) evaluation and refinement.

Many activities within each of these four phases is shown in Figure 1 (Goodman and Love, 1978). Each phase and activity requires a different mix of skills and perceptions for success. From a management perspective, we can group people into three groups viz. project managers/supervisors (hereafter referred to as supervisor); Jr. level managers/middle level supervisor cum technologists; and basic level field technologists. Members of each of these three groups perform different functions, hence require different skills, tools, insights, perceptions and experiences to do their job well.

A supervisor is required to perform three categories of functions, firstly, dealing with technical aspects of project management, secondly, financial, dealing with management of funds and material resources, and thirdly, personnel, dealing with staff and public. Management is common to all these functions, and requires skills of planning, organizing, directing, controlling, coordinating, monitoring, reporting, and public relations.

A middle level supervisor cum technologist performs the same three functions listed above but in different proportions. This person is much more concerned with technical matters and implementation of the programme, has to oversee work, providing technical inputs in designing and implementing practices and works, is required to deal with people more closely, and has to do much less financial and personnel management.

The basic level field technologist is the grass root technical professional staff, who has to survey, design and implement practices with overall supervision by the middle level supervisor cum technologist. This person is not involved in financial or personnel matters except for hiring manual labour, for measurements and assisting in payments. He/she is required to deal with individual farmers or land holders and has no professional assisting him/her.

Considering the differences in functions of these three levels of staff, it is obvious that each category needs a different mix of skills and therefore training and orientation.

Types of Training Programmes

Training and teaching programmes leading to degrees and diploma are excluded from the purview of this paper. On-the-job training programmes end up with award of certificates.

With respect to time, training programmes may extend from less than one week to as much as six months or longer. The longer the training period, the more likely it is to be comprehensive and more likely to exclude policy makers, decision makers and senior supervisors. The shorter the duration of the training, the more likely it is to focus on one or two specific aspects of a job, to impart specific skills and insights to the participants. Participants of short duration courses could range from policy makers/decision makers to middle level supervisors/field level technologists. In the case of the former group, the course may be a one to four week orientation course; in the case of the latter group apart from focusing on one or two specific aspects of a programme, it may also include refresher courses. Training courses may be run regularly or irregularly with respect to time.

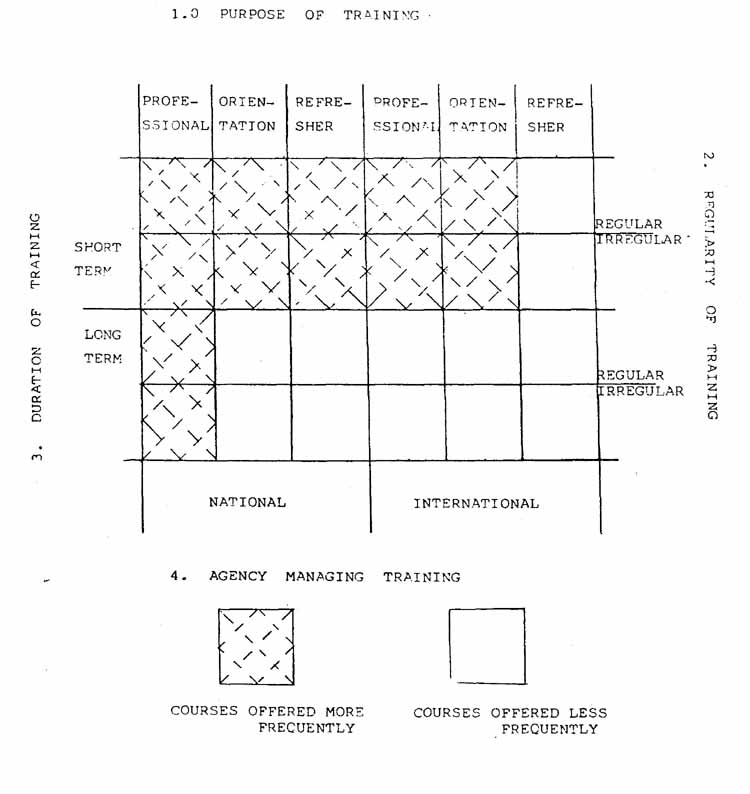

Training programmes may be managed and run by a country itself or may be organized,

managed and run internationally. According to the purpose and levels of participants,

the regularity with which courses are run, the length of courses, and the agency

which organizes the training, courses can be classified as shown in Figure 2.

A short course is one which does not exceed four weeks and is preferably for

a shorter period. A course may be organized by an international agency and yet

offered and managed by a national system for the international agency. This

type of course is still considered international.

Roles and Responsibilities of Parties to Training Programmes

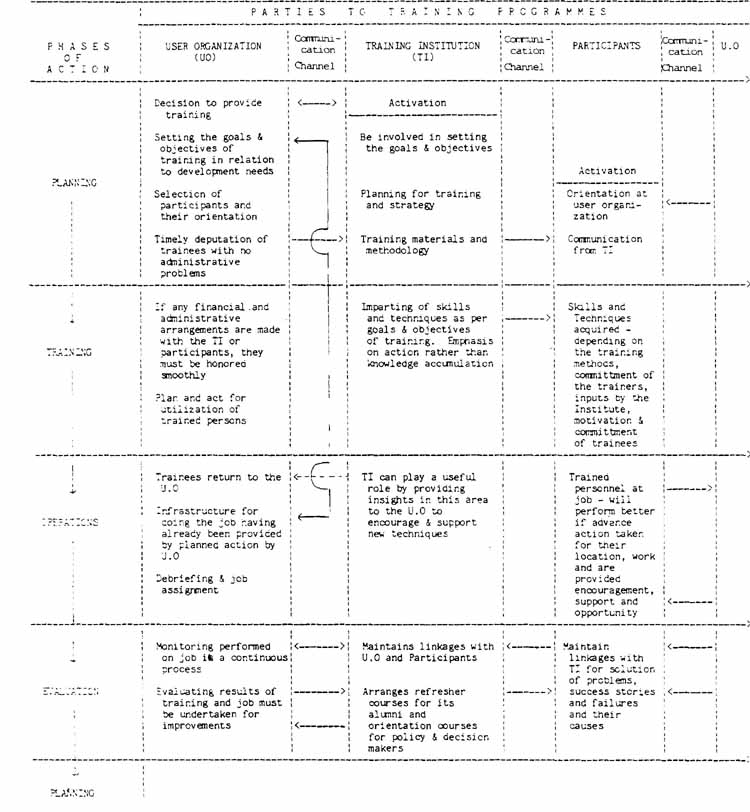

For a training programme to be successful, i.e., deliver the services expected of it, institutions and people doing the training have to play a well orchestrated, enmeshed and synchronized role.

From an institutional standpoint, training programmes require two parties, the user organization (UO) which wishes to train its personnel and the training institute (TI) where personnel are to be trained. From a personnel standpoint, three groups of people can be recognized, namely 0 the managerial/executive or authority group which decides to train personnel as per perceived needs; ii) the trainers (which also includes the managers of the training institute); and iii) the trainees or participants. The role of these three groups is summarized in Figure 3.

i) The management group is expected to:

- define the objectives and goals of training

- define the levels of personnel to be trained

- define the use to be made of the trained personnel

- create infrastructural facilities for the utilization of trained personnel

- coordinate various activities to ensure that participants are selected, oriented,

trained, redeployed in time for both the user organization and the training

institute.

ii) The training group - both trainers and managers of the training institute have to:

- be clear about the purpose of training

- ensure that the necessary infrastructure, materials and methodology of training are in

place on time

- coordinate with the user agency and keep linkages with its alumni for evaluation

and refinement.

While it is the primary responsibility of the user organization to deploy and utilize trained personnel properly, good training institutes should follow up the performance of the persons trained and analyze the causes of good and poor performance to improve and refine the training and skills of their alumni.

iii) The trainee (or participant) group is the main target group on whose training and subsequent implementation skills the success or failure of development programmes depend. This group, therefore, has the responsibility to give its best and imbibe all the necessary skills and insights offered to it. However, having said this, one must again turn back to the role and responsibility of the managerial and training groups.

Although the entire investment of training programmes is usually high, one must realize that the benefits derived are not only for the trainees but ultimately for the project or development programme itself. It is, therefore, very important that trainees are treated as a very valuable resource both by the user organizations and by the training institutions. Before being sent for training, trainees should be briefed by the user organization in terms of why they are being trained and what role they are expected to play after their training. The training institute must then direct its activities to orient and to impart and teach the necessary skills to the trainees. After training, the trainees should be ready to play their allotted role for the user organization.

However, it is often assumed that the objectives of training are achieved when the graduation ceremony is held and trainees return to their organization(s). This assumption is far removed from truth and is one of the major reasons why trained personnel fail to deliver the services expected of them. The user organization must be constantly reminded that training is not a goal in itself but only a means to achieve a goal. At this stage the greatest responsibility lies with the managerial group at the user organization. It is this group which foresees and plans the goals to be achieved after training. It is, therefore, its responsibility to have ensured that the necessary infrastructural facilities have been created and job opportunities provided to achieve the set goals. The trainees, on return, are generally enthused and looking forward to use their new skills and acquired knowledge; nothing is more frustrating and demoralizing than a lack of opportunity and encouragement to use them.

Training opportunities in watershed management can be viewed from two perspectives. In the first case opportunities are available in developed or developing countries. In the second case, they could be considered as either formal education leading to a degree (B.S., M.S. or Ph.D.) or on-the-job training or non-degree training.

Training in the Developed Countries

Among the developed countries, the USA and U.K. offer many opportunities of formal education at the university level.

In a survey of formal education available in the USA, as of December 1977, nine institutions indicated that they offered the B.S. degree, 18 the M.S. degree and 17 the degree of Ph.D., with a major in watershed management, forest hydrology or range hydrology (Ponce, 1979). In addition, eight other schools offered a minor in watershed management (Appendix 1). The survey also indicated that 44 schools in the USA offered a total of 157 courses and five in Canada offered 24 courses in related areas. The survey further indicated a rapid growth in these areas of formal education and it was anticipated that the growth will continue.²,³

In U.K., National College of Agricultural Engineering, Silsoe and Institute of Irrigation Studies, University of Southampton offer courses leading to M.Sc. in Soil Conservation.

Australia and New Zealand, among the English speaking developed countries, and France have well established forestry schools and institutions or universities which offer courses in watershed management sciences. In Asia, Japan is one of the few developed countries with a large number of forestry colleges or universities which offer courses in watershed sciences. However, the institutions in Japan have the limitation that their courses are offered in the Japanese language.

² Many of the schools noted now have additional courses in watershed management/forest or range hydrology; some have courses directed to problems in developing countries (ed.).

³ In the opinion of the author of this paper, the Universities of Arizona, Colorado State, Florida, Georgia, Minnesota, Oregon State, and Utah State are presently the most active in teaching and research in watershed management sciences.

Among the professional training courses in watershed management perhaps the best opportunities in the USA will be available through the Soil Conservation Service, the Forest Service, and Agricultural Research Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The U.S. Department of Agriculture has a full fledged division for International Training which organizes training programmes designed specially for agriculturalists from developing countries. These training programmes are developed in response to priority needs identified by the U.S. Agency for International Development and Food and Agricultural organization project managers around the world. For example, out of the 50 training programmes offered in 1984, five courses were directly related to land use and watershed management, one course was related to training trainers and three courses were related to project planning and rural development (Anon., 1984). These training programmes have the added advantage that many U.S. universities are involved as collaborators. In addition, some U.S. universities now have international schools or programmes offering non-degree training courses in watershed management, e.g., International School of Watershed Management, Colorado State University; International Training Programme of College of Forestry, University of Idaho; International Irrigation Centre, Utah State University and School of Renewable Natural Resources, University of Arizona.

The Environment and Policy Institute of the East-West Centre, Honolulu, Hawaii, offers opportunities for discussion and interaction in socio-economic and policy issues of watershed management programmes to senior level scientists, policy people and decision makers.

In Europe, National College of Agricultural Engineering, Silsoe, U.K.; University of Gembleux, Belgium (French language); University of Padova, Italy; International Institute for Aerial Survey and Earth Sciences (ITC), Netherlands; and Institut d'Hautes Etudes d'Agronomie de Mediterranean, University of Montpellier, France, offer training programmes in watershed management sciences.

Among the international institutions, International Institute of Tropical Agriculture, Nigeria; International Crops Research Institute for Semi-arid Tropics, India; Centro Agronomico Tropical de Investigacion y Epsenanza (CATIE), Costa Rica; Asian Institute of Technology, Thailand; United Nations University, Japan; and Centro Interamericano Desanouo Integral de Aquas y Tierras (CADIAT) focus on watershed management sciences and can be useful centres for training programmes.

Training in the Developing Countries

As reported earlier in this paper, training opportunities in the Asia-Pacific region are either nonexistent or grossly inadequate. With respect to formal education, Kasetsart University, Thailand, and the College of Forestry, University of Philippines, Los Baños, offer courses in watershed management at B.S. and M.S. levels. In India, courses in soil and water conservation engineering are offered at a number of agricultural universities and the institutes of technology. Indonesia, similarly, has a number of courses and schools. However, no degrees in watershed management are offered.

In Latin America there are many forestry schools, but only a few offer courses in watershed management sciences, e.g., Facultad de de Florestas (Cursao de Engenharia Florestal), Universidade Federal do Paraha, Parana, Brazil; Departamento de Engenharia Florestal, Centro de Ciencias Agrarias, Universidede Federal de Vicosa, Minas Gerais, Brazil; Escuela de Ciencias Forestales Universidad de Chile, Santiago, Chile; Departamento de Recursos Forestales, Facultad de Agronomia, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Medellin, Colombia; Departamento de Bosques, Universidad Autonoma de Agriculture, Chapingo, Mexico; Universidad Nacional Agraria - La Molina, Lima, Peru; and Facultad de Ciencias Forestales, Universidad de los Andes, Merida, Venezuela.

With respect to non-degree training programmes in soil and water conservation and watershed management, China, India, and Thailand currently have the best facilities and opportunities, while Indonesia and the Philippines have satisfactory facilities and opportunities. Facilities in India can be utilized (and are utilized to a limited degree) by the international community as the programmes are offered in English for supervisors and middle level field technicians. India offers different types of training programmes, namely professional, refresher, and orientation at the Central Soil and Water Conservation Research and Training Institute and its regional centres all over India. In addition, various resource based institutes of I.C.A.R. can offer short, specially designed courses in different watershed management sciences, e.g., National Bureau of Soil Survey and Land Use Planning; Central Arid Zone Research Institute; Indian Grassland and Fodder Research Institute, etc. in addition, National Remote Sensing and Photo-interpretation Institute, Dehradun, provides excellent training programmes in resource surveys and project planning. Uniquely, India and Pakistan in South Asia provide forestry training and education by the Central and State Governments through forest research institutes and colleges rather than universities. These institutions offer courses in soil and water conservation/watershed management in the regular training of forest officers and forest rangers.

In Thailand, Kasetsart University and the Northern Regional Agricultural Development Center have developed facilities to offer sponsored training programmes in watershed management.

In addition to the above, international agencies, specifically the Food and Agricultural Organization, arrange a number of training courses in watershed management in developed and developing countries, e.g, FAQ Training Courses in Watershed Management in Kenya (for Africa) and Italy (for Spanish speaking people).

Considering training facilities globally, one is tempted to generalize that even though training opportunities in the Asia-Pacific region are inadequate, they are relatively better than those available in Africa and Latin America. It follows from this conclusion that the training opportunities in the Asia-Pacific region need a two pronged approach, namely creating new opportunities and simultaneously strengthening and improving existing opportunities. In Africa and Latin America, for sometime to come, there will have to be [greater] emphasis on creating new training opportunities.

Given that there is need to create training opportunities in watershed management globally, we need to identify the key factors which contribute to the development of successful training programmes. The key factors for successfully creating and running training programmes include: awareness, planning, organizing, operating and evaluating.

These functions are not totally independent. They are often performed simultaneously by one or more persons, rather than sequentially, and require considerable interaction. Some aspects of these factors have already been highlighted. However, this section emphasizes the role of policy makers, decision makers and programme directors.

Awareness

Awareness that any technology to be applied needs trained personnel is the first and foremost factor which leads to the establishment of training programmes. If we look around the world, we will observe more often than not, that development activities are started in developing countries with little or no regard for the need of trained personnel. Consequently, there have been costly failures of programmes and in the process, the programmes themselves have been set back in the eyes of beneficiaries. While many policy makers and decision makers promote watershed management programmes, few are fully aware of the importance of trained personnel to the extent that they are willing to start or support training programmes. However, the impacts of programmes are so important and dependent on trained people, that matters cannot be left to luck. Those who are promoting development programmes must ensure that training activities are inscribed in the project and implemented without fail.

Planning

Planning functions are primarily performed by policy makers, decision makers or programme directors. It is essential for the persons involved in this exercise to look to the future -say at least 10 years -- and visualize the development needs and type of personnel needed and then plan the development and training programmes in concert. It is at this stage that a commitment for training personnel, support staff and materials has to be made on a sustained basis to provide for effective training activities. Trainers have to be aware of the need for training, and be committed and oriented to the development programmes. Materials include equipment, library, transportation, and space for teaching, living, and recreation. Concerning equipment and the tools, one should be cautious that while trainees should be made familiar with the latest techniques, they should also be trained to utilize techniques and equipment which are more likely to be available to them in the field. All these cost money, yet if we look around the developing world, even where training needs have been supported, there is usually insufficient funding for training. Even though training costs money, the investment is only a minor fraction of the total investment for the entire development programme but a major factor in determining its success. So. the conclusion is that personnel, materials, and money should be provided commensurate with the needs and the tendency to cut off or short change training funds should be curbed.

Organizing

The training director usually has the job of organizing training and providing the leadership. He/she is like the conductor of an orchestra who puts all the pieces together for a symphony. The training director has to recruit trainers and staff, arrange for space, equipment and transport, lay down operational procedures, assign duties, delegate authority, develop monitoring, evaluation, and reporting procedures, arrange for funds, etc. This person is a key to the success of training programmes, as his/her leadership and personality not only influences the trainers but also affects the participants directly as well as indirectly through the trainers. The training director needs to have the confidence and support of the planner and decision maker and needs to be delegated sufficient authority to make decisions in the discharge of his/her duties. The training director also has to be sufficiently dynamic as to acquire authority since in the developing world authority is generally not delegated easily. As is true of any manager, a training director has to deal with people and, in addition to being a good professional, he/she has to be sensitive to the needs, aspirations and problems of the staff and trainees of the Institute.

Operating

The operating function of a training programme is concerned with action, including directing, coordinating and controlling activities of the training director and the trainers. This section discusses the functions of the training director only.

Directing activities would involve: communicating with and directing the trainers and staff to implement the training programme; being sensitive and aware of the constraints and problems which arise in implementing the training programme; overcoming constraints and problems due to local conditions within the institute, which will need to be resolved on the spot; and overcoming constraints that may be inherent in the plan and organization, which will need to be modified and adapted to the actual experience.

Coordinating activities within and outside the training organization is one of the director's primary jobs. Coordination activities within the organization include: effective communication with the supervisors (or staff) regarding the role each one has to play; providing leadership and facilitating communication between supervisors, and the exchange and application of ideas and innovations; effective and efficient utilization of equipment, materials and transport (often in short supply in the developing countries); and guiding, demonstrating and helping the supervisors/trainers/staff in their professional and personal activities. Coordination activities outside the organization include: liaison, collaboration and coordination with other related institutions for mutual benefit; supplementing the faculty with experts/ trainers of other institutes and maintaining good public relations with the community where the training institute is functioning.

Controlling activities while including coordination activities also include: monitoring quality and quantity of instructions; application of appropriate financial and administrative procedures; ensuring timeliness of all operations; evaluating the performance of supervisors/ instructors/staff; and maintaining appropriate records of professional, financial and administrative activities.

Evaluating

The evaluating function is a constant and conscious effort exercised both during the training programme and after a training programme is completed. Elements of evaluation should be interwoven in the operating functions discussed above.

Even though training opportunities are limited and costly, it is indeed surprising that training opportunities are not effectively utilized. The role of the user organization in the training cycle is critically important and has been already discussed. Some of the more outstanding problems encountered which need serious consideration at the level of policy and decision makers are discussed below.

Utilization of Trained Personnel

Sometimes people are trained because there is a training programme being offered, sometimes there is a genuine need of trained personnel and a job is waiting to be done by them. However, it is a common experience in many or all the developing countries, that after a person is trained, he/she is not put on the job for which the training was given but is diverted to another job. The user organization may consider the other job more important or the person trained may not wish to work in the job for which he/she was trained and manages to get out of it. Diversion of trained personnel to other jobs is a reflection of poor planning and poor personnel management and should be avoided.

Too Many Training Opportunities

While there may be limited or insufficient training opportunities in specific areas of development, there is also a corresponding and parallel phenomenon of availability of large total number of training opportunities in many related fields, for example, soil survey, land use planning, remote sensing, watershed management, forest hydrology, range management, water resource development, rural development, etc. In some cases these opportunities, coupled with the limited person power in developing countries, result in some individuals being almost continuously trained. In the meantime, their job is not completed and opportunities for meaningful personnel development are effectively wasted. It is the duty of a decision maker to link up training opportunities with the appropriate needs (benefits) for the programme. It is perhaps more useful in the long run to forego a training opportunity rather than forego an opportunity of putting a trained person on a job waiting to be done. Sometimes rules stating that a person should not be given another similar or related training for 3-5 years after completing a training course leads to more effective use of training opportunities.

Inappropriate Training

The problem of inappropriate training, more often than not, is related to the training of personnel of developing countries in the developed countries. This is a genuine problem of communication, appropriateness and appreciation of socio-economic conditions. Both parties, the developed and the developing countries, are sincere and mean business, yet the returning trainee often feels frustrated because the techniques and skills which were taught are not directly applicable -- due to various biophysical and socio-economic reasons -- to the solution of the problems in his/her country. Few people are able to adapt and innovate, a large proportion of the others feel frustrated, defeated and give up.

This problem needs to be recognized squarely and attempts made to solve it.

It may never perhaps be resolved to the satisfaction of everyone, yet some of

the solutions could be:

4 Several universities in the developed countries now offer courses and

programmes that focus on the special problems of and solutions for resource management

developing countries (ed.).

i) Training a person in a developed country for most of the time but exposing him/her to successful adaptation/innovation of technology in a developing country for part of the time to build confidence.

ii) Establishing demonstrations with personnel of developed and other developing countries within the country.

iii) Insure that people are sent for training to institutions or programmes which at least have some bearing -- even though distant -- on the programmes and ecological conditions of the developing country.

As international training opportunities are not only limited in number but are also costly, it is imperative that the policy maker/decision maker/user organization send personnel to the appropriate institutions. For example, training a person from a least developed tropical country in a watershed management programme that emphasizes temperate, snow hydrology problems and solutions is of minimal value. Similarly, programmes in a university of a developed country where the problem relates to water quality for recreation rather than sediment free water for irrigation, or where management is aimed at wildlife habitat and recreation rather than for meeting upstream needs of people for food, fodder, fuel, and water for on-site irrigation and drinking, are not good matches.

The establishment of international training institutes in watershed management in the developed countries themselves is a desirable goal. These institutions would obviously need to be regional in character, i.e., for South Asia, South East Asia, Pacific Islands, and different regions in Africa and Latin America as the situation may require.

Why Research is Necessary

It was mentioned in the introduction to this paper that a "Research, Demonstration and Technological Package" is one of the five areas of action leading to successful watershed management programmes. What constitutes these programmes must be clearly defined.

Watershed management in India, for example, has been defined as "Rational utilization of land and water resources for optimum and sustained production with minimum hazard to natural resources. It essentially relates to soil and water conservation in the watershed which means proper land use, protecting land against all forms of deterioration, building and maintaining soil fertility, conserving water for farm use, proper management of water for drainage, flood protection, sediment reduction and increasing productivity from all land uses."

Understanding the behavior and response of watersheds to management practices requires a multidisciplinary knowledge of many biophysical sciences such as geomorphology, geology, soil science, meteorology, hydrology, engineering (drainage, structures, etc.), agriculture, forestry, agrostology, etc., and socio-economic sciences like resource economics and resource sociology. If technological packages are to be developed for application in the field, it is obvious that they have to be put together by an organized effort of research and trials.

Among the developing countries, perhaps the example of India is worth citing. It is the measure of the urgency of soil degradation problems of India as well as the country's farsighted planning that a long range benefit programme like soil and water conservation was given an important place with the beginning of planned development in 1951. Between 1951-1978 India had treated 21.8 million ha of land, with soil and water conservation programmes on agricultural lands, degraded forest and grass lands, and waste lands (Anon., 1978).

However, when the soil and water conservation programme was included in the First Five Year Plan (1951-56), it was obvious to the planners that while the problems of degradation and destruction of the production base were broadly known, their solutions backed by scientific investigations were. Not available. Consequently, a chain of Soil Conservation Research, Demonstration and Training Centres was established in the First Five Year Plan and the Second Five Year Plan. These centres were charged with the responsibility of conducting research on all land uses but on a watershed basis.

Present Status of Research in Watershed Management

FAO (1982) recently evaluated the present status of research and demonstration in many countries of the Asia-Pacific region (Table 2). Apart from India, China, Thailand, Indonesia and Philippines, no other country in the Asia-Pacific region has satisfactory research infrastructure. In fact, in most countries of the region it is nonexistent. This is also true of Latin America (with the exception of Brazil and Venezuela) and Africa (with the exception of East Africa, Zimbabwe and Nigeria). This is not surprising because the long-term nature of watershed management programmes make them less attractive to policy and decision makers in developing countries who are more concerned with quick, short-term results. However, with greater awareness of the problems of land degradation, destruction of the production base, and mounting pressures of population on land and water resources, developing countries are [becoming] generally willing to invest in research and development programmes in watershed management.

Details of research infrastructure in individual countries such as Pakistan, China, Thailand, Indonesia, and Philippines are reviewed by FAO (1982).

| Present Status of* | |||

| Country | Research Facilities |

Research Personnel |

Demonstration Areas |

| Pakistan | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| India | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Nepal | 5 | 5 | 3 |

| Bhutan | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Bangladesh | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| China | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Burma | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| Thailand | 3 | 3 | 1 |

| Lao | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| Sri Lanka | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Indonesia | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| Philippines | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Fiji | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Tonga | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Western Samoa | 5 | 5 | 5 |

Present status is evaluated as 1 = Excellent; 2 = Good; 3 = Fair; 4 Unsatisfactory and 5 = Very Unsatisfactory.

Type of Research Needed

Research may be classified as fundamental, basic and applied. Fundamental research has no obvious [direct] practical and immediate objective and application.' It is the result of man's natural inquisitiveness and adds to the broad base of human knowledge.

Basic research consists of studies of individual processes and how they can be changed by controllable variables. Basic to watershed management would be studies of such processes as interception of rainfall, infiltration, runoff, soil-water movement, soil detachabiity, soil transportability, erosion processes, sedimentation, hydraulic characteristics of conservation structures, etc.

Applied research investigates various treatments which have practical application. Based on information from basic research, treatments would be designed to modify several processes in such a manner as to bring about a desired change. Examples of this would be studies of various crop rotations, cover cropping systems, grass and tree covers and soil conservation structure to reduce runoff and erosion rates. In general, basic research will explain "why" and applied research will explain "what happens." Both types of research are needed to develop technological packages for effective and efficient watershed management programmes. However, determining the mix of basic and applied research (depending upon the availability of resources and the urgency of the need for developing technological packages) calls for qualities of judgment and leadership on the part of policy and decision makers.

Relevance of Research

Research is expensive, no matter whether it is carried out in developed or developing countries. In developing countries, where human and animal population pressures on land and water resources are intense in upland watersheds and where standards of living are low, it is difficult to promote "erosion" control programmes only. What the people need foremost is economic security and then they may be inclined to work towards ecological security. Matters for investigation should, therefore, be subjected to the utmost scrutiny to ensure their relevance to the problems at hand. Research should, in all cases and without exception, be directed to promote soil conservation, combat soil erosion and degradation by developing technological packages which are technically feasible, economically profitable and socially/culturally acceptable. As there is a limited data base in developing countries, it is often difficult to fight the tendency towards conducting more basic rather than applied research. For example, research should emphasize watershed development activities rather than simply watershed monitoring.

Organization of Research

The objective of watershed management research in developing countries, should be to devise and develop, as expeditiously as is practical, a relevant, suitable, and acceptable package of practices for watershed management. For any area, state, or country, research may result from one or more of the following three sources:

i) Research conducted elsewhere but having a possibility of application with or without adaptation to the area. One example of adoption of proven techniques for use in similar areas is the study of landslides in the western Ulucuru Mountains of' Tanzania (Temple and Rapp, 1972). More than 1,000 landslides were triggered by sudden heavy rainfall in Tanzania in February 1970. A study of geomorphological effects of sudden heavy rainfall was conducted at the site between March-July 1970. Within a short span of time it was concluded that the slide forms and release mechanisms were closely comparable to those described in Brazil, Salvador, New Guinea and USA. The results showed that the only feasible means of restricting landslide damage is by modifying current land use practices.

ii) Previously conducted research (reported/not reported in the literature) from the area.

iii) Research to be initiated in response to the need of development programmes.

The sources of information and the development of technological packages are

dynamic in nature. At any time all of the above three sources of information

may be used simultaneously. It is not the objective of this paper to indicate

how the research infrastructure is to be developed. The functions of awareness,

planning, organizing, operating and evaluating, as previously described for

developing successful training programmes, will be equally applicable in developing

research programmes.

When the technological practices or packages are developed, research institutes and

researchers should be required to demonstrate how the results of their studies can be

applied. Insistence on this would stimulate more relevant research, more efficient use of

research personnel, money, and materials, assure a better return on investments in

research, and should attract more funding for research. It is desirable, to demonstrate

watershed management techniques in pilot projects or operational research projects.

Demonstrations

Pilot watershed projects or operational research projects will not only produce biophysical responses of management practices but will also provide feedback from people in the watershed with respect to their priorities and acceptance of the practices. This will enable researchers to suitably modify either the individual practices or the mix and priority of practices. One of the most outstanding findings of operational research projects in India has been that the people living in upland watersheds put low priority on soil conservation and sediment reduction (as they perceive the former to be of long range benefit and the latter as an off site benefit). Thus, even though they are short of fuel and fodder, they are not enthusiastic about afforestation and grassland development. Their first priority is local water resource development for surface irrigation and drinking water because they perceive this activity as of immediate, on site, direct benefit to them. Thus, a pilot watershed project or operational watershed research project serves the purpose of pretesting and refining a package before it is implemented and expanded to a large scale watershed management programme.

Among the countries of the Asia-Pacific region it is only India, Nepal, Thailand, Indonesia and the Philippines (and Costa Rica in Latin America) which have established demonstrations or pilot watersheds and operational research projects (Table 2). it is noteworthy that Nepal, inspite of appropriate research back up, has gone ahead with demonstrations and pilot projects on the basis of technological packages developed elsewhere. However, it is imperative in all cases, that the demonstration or pilot watershed and operational research projects be evaluated so that appropriate lessons are learned, packages are refined and then transferred to large scale development programmes. So far these have not been accomplished as a result of pilot watershed projects. This also presupposes a very close and active linkage between the research set up and the developmental agencies, which again is often lacking.

Anonymous. 1978. Report of the working group on soil conservation and land reclamation for 1978-79 to 1982-83. Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation, Govt. of India, New Delhi.

Anonymous. 1984. Catalog of courses in agricultural and rural development. USDA International Cooperation and Development. Washington, D.C.

FAO of the United Nations. 1982. Watershed management in Asia and the Pacific. Problems, Needs, Status of Programmes and Strategy to foster upland conservation in the region. Technical Report FO/DR/RAS/81/053.

Goodman, K. J. and R. N. Love. 1978. Guidelines for writers of case studies. East-West Center, Honolulu.

Ponce, S. L. 1979. Formal education in wildland hydrology and watershed management in North America. Water Resources Bull. 15(2): 530-535.

Tejwani, K. G. 1979a. Malady - remedy analysis of soil and water conservation in India. Indian J. Soil Conser. 7(l):29-45.

Tejwani, K. G. 1979b. Soil and water conservation -- promise and performance in the1970's. Indian J. Soil Conser. 7(2):80-86.

Temple, P. H. and A. Rapp. 1972. Landslides in the Mgeta area, Western Uluguru mountains, Tanzania. Geografisca Annalec. 54: Section 9A.

Vohra, B. B. 1974. A charter for the land. Soil Conserv. Digest 2(2):1-25.

Source for updating information

FAO of the United Nations. 1981. Forestry Schools. FAO Forestry Paper 3 rev/1. FAO, Rome.

I wish to acknowledge with thanks the benefit of personal discussions and inputs provided by L. S. Botero, Chief, and Tage Michaelsen, Forest Conservation officer, Forest and Wildlife Conservation Branch of the Forestry Department, FAO, Rome, and W. D. Striffler, Professor of Watershed Management, Colorado State University, Fort Collins.

| Number of Courses | Degree Program |

||

| Institution | Major | Minor | |

| University of Alaska | 1 | No | No |

| Auburn University | 1 | No | No |

| University of Arkansas | 1 | No | No |

| University of Arizona | 10 | BS, MS, PhD | Yes |

| Northern Arizona University | 2 | No | No |

| California Polytech. State University | 3 | No | No |

| Clemson University | 4 | No | No |

| Colorado State University | 12 | BS, MS, PhD | Yes |

| Duke University | 2 | No | No |

| University of Georgia | 6 | BS, MS, PhD | Yes |

| Humbolt State University | 8 | MS, PhD | Yes |

| University of Idaho | 3 | MS, PhD | Yes |

| Southern Illinois University | 2 | No | No |

| Iowa State University | 4 | MS, PhD | Yes |

| University of Kentucky | 4 | No | No |

| University of Maine | 4 | No | No |

| University of Massachusetts | 1 | No | No |

| Michigan State University | 2 | MS, PhD | Yes |

| Michigan Tech. University | 4 | No | Yes |

| University of Minnesota | 2 | MS, PhD | Yes |

| University of Montana | 6 | MS, PhD | Yes |

| University of Nevada | 5 | BS, MS, PhD | Yes |

| University of New Hampshire | 4 | BS, MS | Yes |

| State University of New York Syracuse | 6 | MS, PhD | Yes |

| North Carolina State University | 1 | No | No |

| Ohio State University | 1 | No | No |

| Oklahoma State University | 2 | No | No |

| Oregon State University | 6 | MS, PhD | Yes |

| Pennsylvania State University | 3 | No | Yes |

| Purdue University | 1 | No | No |

| Stephan F. Austin State University | 3 | BS, MS, PhD | Yes |

| University of Tennessee | 1 | No | No |

| Texas A&M University | 5 | BS, MS, PhD | Yes |

| Texas Tech. University | 3 | No | No |

| Utah State University | 10 | BS, MS, PhD | Yes |

| University of Vermont | 1 | No | No |

| Virginia Polytech. Institute | 1 | No | No |

| University of Washington | 7 | No | Yes |

| Washington State University | 3 | No | No |

| West Virginia University | 3 | MS, PhD | Yes |

| University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point | 2 | BS | Yes |

| University of Wyoming | 1 | No | No |

| Yale University | 3 | No | No |

| University of Alberta | 3 | No | Yes |

| University of British Columbia | 9 | MS, PhD | Yes |

| University of Laval | 4 | No | Yes |

| University of New Brunswick | 6 | No | Yes |

| University of Toronto | 2 | No | Yes |

| Universidad Autonoma Chapingo | 1 | No | No |