In the past, rural "development" in mountain watersheds and other critical areas was carried out on an ad hoc basis, with the disadvantage that it often ran down the natural resource base. In Colombia, for example, uncontrolled settlement destroys a million hectares of forest each year: the uneconomical and technically inappropriate techniques used by nomadic farmers degrade the soil and destabilize watersheds (FAO/SIDA, 1980). Similar situations are found in Jamaica (FAO/SIDA, 1980), Paraguay (Salcedo, 1981), and Venezuela (de Camino, 1983). If mankind is not to repeat these mistakes, which it-can ill afford, rural development in critical areas must be based on plans and projects targeted at rural participation, and the rehabilitation of degraded resources, not to mention the conservation of those which are still productive (in the broadest sense).

The justification for conservation programmes in mountain watersheds and other critical areas can be seen more clearly by looking briefly at the causes and consequences of renewable natural resource degradation and at the positive effects of conservation projects. The knowledge thus gained will help identify the direct and indirect costs of these plans and programmes as well as their direct and indirect benefits, which, through the use of different kinds of incentives, have an important contribution to make to policies and strategies.

Many different situations reflect the relationship between natural resources and population, but the numerical relationship is not the only important factor. That resources differ in their potential and populations in their characteristics is important as well.

Although somewhat of a simplification, most basic situations will be assumed to fall into one of three categories, (FAO, 1980):

- Areas where high population density and growth per km² have saturated all available land, bringing strong pressure to bear on land use.

- Areas where although population density is not particularly high the land tenure system prevents peasants from gaining access to land, putting strong pressure on the remaining land available.

- Arid and semi-arid areas degraded by poor cropping practices, torrential storms and uncontrolled grazing.

The results in each case are similar - marginalization of both the land and the population (FAO, 1980).

A clear idea of these situations can be obtained by analyzing what happens in the world's three thousand million hectares of arable land. In developed countries, seventy-seven percent of this land is utilized; the population has either stabilized or is growing very slowly, and advanced technology is the rule. In developing countries, however, only thirty-six percent of the total arable land is actually cultivated, though the problem varies by region: in South-east Asia, ninety-two percent of arable land is cultivated, whilst in Latin America the figure is only fifteen percent (FAO, 1983). In South-east Asia, the problem is intense population pressure, whilst in Latin America it is inappropriate structures(with few exceptions).

In some parts of the world population density is enormously high: in Indonesia, it is 690 inhabitants/km² : in Korea, 316 inhabitants/km² (FAO, 1983) (FAO, 1976).

Just as anywhere else, the peasant population in these regions has basic needs which it has to try and meet from the available resources:

- Basic plant and animal foods such as maize, beans, rice, cassava, poultry and other meats, milk, etc.

- Energy for heating and cooking.

- Timber for building.

Large populations produce a need for land for cultivation and fertilizers for maintaining soil fertility. Energy, particularly in non-oil producing or exporting countries, requires forests to meet people's fuel needs, in addition to forest products for house-building.

The agricultural sector in these countries generally consists of stable small holdings. Shifting cultivation is a thing of the past due to the falling land/man ratio,; consequently, there is no fallow period, so the soil only has a chance to rest during the seasonal gap between two successive crops.

Small holdings are as much a feature of mountain watersheds as of medium and low-lying areas, although the first two are obviously exposed to a greater degree of soil degradation.

Not only does the population need to be able to cultivate land intensively and uninterruptedly, it also requires fuelwood; the amount varies between 0.5 and 2.0 m³/person/year, depending on climate (de Montalembert and Clement, 1983). A better idea of what this type of pressure means can be had by imagining a country with a population density of 300 inhabitants/km²: fuelwood consumption would amount to 1 m³ /inhabitant/year (the equivalent of 300 m³/km²/year of wood from a forest growing at an annual rate of 3 m³/ha). If, in addition to fuelwood demand, we add food and small animal requirements, the pressure on land is enormous and demand almost impossible to satisfy.

The causes of this pressure are high population density, the resulting fragmentation of holdings, and the population's need for food and energy.

This has serious consequences for the land because:

- Land is cultivated without a break, year after year, gradually exhausting the soil; if no steps are taken to conserve or protect the soil, not only will productivity fall off, but erosion by water will also result. The use of inappropriate technology further diminishes productivity (FAO/WFP,1984)(FAO, 1980).

- When there is no land suitable for crops, the population is forced to look to more marginal and fragile areas where slopes are steeper and covered with shrubs or trees. Soil fertility is even lower here, and erosion quicker and more serious (Burley, 1982) (Saouma, 1981) (FAO, 1978).

- At least ninety developing countries will be affected between now and the year 2000, seventeen of which will contain half the world's population and 90% of utilized land; in other words, a critical land shortage will result (FAO, 1983).

- The demand for fuelwood and charcoal will put further pressure on land. Extending cultivation to shrub and forest land can initially, through felling, go some way towards meeting energy requirements. Where such land is cultivated, and the remaining forest is too far to be accessible, the population will be forced to collect crop residues or animal manure to dry for fuel (Saouma, 1981). The effect of this is to deprive intensively cultivated and steeply sloping land of valuable soil nutrients which used to help preserve its moisture rentention capacity. Unfortunately, vast areas of the earth, such as Niger's Zinder region (Sanger, et al, 1977), the Gujarat region in India (Burley, 1982) and Korea (FAO, 1983) have already reached this point.

Even where shrub and tree stands remain, peasants have to spend increasing time and effort gathering the minimum amount of wood needed for cooking and heating. Unfortunately, this state of affairs occurs much more frequently than most people imagine. It also causes sociological problems: for example, when diet has to change due to the shortage of fuelwood for cooking; or when the religious cremation of corpses is no longer possible. (Burley, 1982) (Bong Won Ahn, 1978) (de Montalambert and Clement, 1983) (Flinta, 1983).

The consequences of this are (Bochet, 1983) (FAO/WFP, 1984) (Saouma, 1981) (Burley, 1982):

Forests become degraded and eventually disappear altogether.

Fertility and productivity of arable land declines and exposed topsoil is washed away by rain.

Streams are loaded with suspended sediment and flow becomes irregular and variable, with periods of low water followed by flooding due to the silting up of river-beds. This can cause serious damage to downstream populations, works and crops, necessitating heavy infrastructural investment on irrigation and energy.

The population sees it food supplies and income reduced, forcing people to migrate to heavily congested cities where prospects for them are little better.

By "not subject to population pressure" is meant less population pressure than in the above areas, around 60 to 70 inhabitants/km2 (or even less). This is the case in most Latin American and some Central American and African countries, as well as in those developing countries where the phrase has a specific social connotation.

These countries are characterized by a combination of large estates (latifundia) with extensive tracts of land concentrated in the hands of a few landowners, and numerous small holdings (minifundia) which together constitute only a small percentage of total arable land but a high percentage of owners and occupiers (Hidalgo, 1981). As a rule, the large estates are to be found in the lowlands of the valley where land is more suitable for farming and livestock-raising, in piedmont areas, where the soils are especially rich, and in the large mountain forests; clusters of small holdings may be found in each of these categories, providing a source of temporary labour for the big estates. The State should not be overlooked either, since it owns large areas of uncultivated land, forest reserves and national parks.

With several different structures all operating at the same time, the causes of soil degradation vary:

The traditional latifundio is extensive farming, catering more to the needs of the owner than those of local peasants or the country at large. Yields are not particularly high and little direct damage is caused to natural resources. However, since natural resource conservation measures are very rarely taken, the forest gradually gives way under pressure for new farming land or from commercial . logging and no attempt is made to replace it by replanting or natural regeneration. This type of degradation is only noticeable after many years, by which time it is usually irreversible unless appropriate restoration measures are taken.

Latifundia though can also involve intensive crop-livestock association in (generally) flat areas with large injections of capital and technology: unfortunately this type of farming produces erosion, one of the saddest instances being the wind erosion experienced in the Great Plains area of the United States (USDA, 1957) where, after several decades of intensive cropping on light soils, a storm blew away all the soil in a couple of days with the serious economic and social consequences that were so well described by John Steinbeck in "The Grapes of Wrath".

In mountain areas in developing countries one can also find upland forest latifundia which are exploited for timber and products. Reference has already been made to new legislation which now restricts indiscriminate logging of particular kinds, species or areas. Nonetheless, these latifundia have been responsible for destroying many valuable forest species, degrading forests through over-exploitation, major forest fires, and the erosion of fragile soils in both temperate and tropical zones. In this respect, the process has not been very different from the previous two examples of latifundia - the traditional kind in particular. This is because the national and transnational companies which own them do little to rehabilitate the resources they have degraded, and treat the forest more as a mine than a renewable natural resources.

The destruction of forest cover causes extensive run-off which not only encourages soil erosion but can also produce serious downstream damage from flooding and heavy alluvial deposits which silt up reservoirs (FAO/WFP, 1984) (Gregersen, Brooks, 1978).

State forest latifundia; forest reserves, national parks or other kinds of State forest, given an effective forestry service, may develop into a valuable source of employment and production because of the wood produced by licensees or by the State directly. Properly equipped national parks may act as important gene banks, as well as providing communities with recreational facilities, something which small towns in the less developed countries have yet to appreciate fully.

However, in the less developed countries the state latifundio exists alongside forest services which are either flimsy and inadequate or bureaucratically top-heavy with little practical relevance. This gives rise to the following problems:

Concession holders in forest reserves do not respect forest management plans,and silviculture as an investment to maximize the profitability of their own operation is not practised.

Not even forest reserves managed directly by the Sate respect management plans as their potential is often nowhere near exploited to the full and supervision is very unreliable. Venezuela, for example, had 11 million hectares of forest reserves in 1974, but only 120 thousand of these were in production and only a tiny fraction of the 4.7 million hectares of national park were given over to recreation (de Camino, 1983).

National parks are rarely fully operational and so cannot fulfill their mandate. Recreational facilities are restricted to the few small areas open to the public.

Given the neglect of the original purpose for which the reserves were intended, a certain amount of unauthorized logging goes on with little State control, which impoverishes the forest as only the best species are cut. In extreme cases, forest cover is so reduced as to cause erosion. Poorly monitored State forest reserves and parks are seen by peasant smallholders as giving them scope to practise shifting cultivation. Whether or not soil degradation ensues, nothing can compensate for the loss of the forest itself, and particularly the protection it provides (Petriceks, 1959). In addition, it is common for small hill farmers to live by cultivating small areas using primitive techniques and to move on as soon as the soil shows signs of erosion and loss of fertility. (Rodriquez, 1980) (Braun, 1974).

This type of situation is characterized by poor distribution of resources (landless peasants vs. latifundia), resulting in increased pressure on land. Another kind of serious social problem arises in the remoter parts of tropical forests, when scattered native communities contract diseases as a consequence of companies working in the area, and see their traditional forms of production, such as hunting, gathering, and shifting cultivation, threatened (FAO, 1978).

Inadequate procedures for allocating and settling forest land for agriculture have often resulted in degradation of renewable natural resources. The problem is not population pressure, but the fact that the land's potential does not correspond to using it for cropping, and lack of capital means the settler cannot devote enough time to forest cultivation since he needs to earn money quickly in order to survive (Burley, 1982). This -type of situation is often found in the tropics and this is why it has now become essential to reorganize production (Finol, 1978) in response to resource abuse and population problems likely to have a greater future impact in the region than in the high density South-east Asian countries (FAO/SlDA, 1980) (FAO, 1980) (Botero, 1984). Upland areas have long been neglected by policy-makers, most public development bodies having concentrated on the lowlands. In other words, there has been a failure to recognize that the cause of the erosion problems on which so much money has been spent in the lowlands originate upstream (Hidalgo, 1981).

Degradation in arid and semi-arid areas poses a special type of degradation problem because of their low productivity and the fact that, despite a relatively low population density, the carrying capacity of local or regional ecosystems is taken up entirely by demand for basic foodstuffs. The expanding world population and its growing demands has put increasing pressure on arid and semi-arid lands, depressing productivity and causing desertification (Burley, 1982).

In these areas population pressure is basically expressed as livestock production practices and fuelwood consumption. Crops are of marginal importance, only being cultivated in the few areas close to water.

A string of negative consequences results: deforestation due to increased grazing and cropping; direct and unauthorized cutting for fuelwood and heating; debarking of trees for tanning purposes; deliberate forest fires to facilitate grazing and wood and charcoal production; overgrazing and exceeding the carrying capacity of the land; poor management and irrational exploitation of forest stands (Hamza, 1978).

The population has remained fairly low in the most arid grazing lands but the number of head of livestock has increased markedly, reducing natural forests to virtual remnants (FAO, 1978).

Population pressure on grazing land and fuelwood usually leads to deterioration in soils and the water regime. Soil degradation is caused by trampling (Bochet, 1983) and also by the removal of vegetation - the loss of cover exposes soils to wind erosion and weakens their resistance to torrential rains, producing water erosion (FAO, 1983) (Bochet, 1983). Wind and infrequent torrential rainstorms combine to unleash desertification, which has reached particularly critical levels in the Sahel countries, North Africa, Ethiopia, Jordan and some parts of India (Le Heurérou, 1970) (FAO, 1983) (Burley, 1982) (Sandahl, et al, 1978).

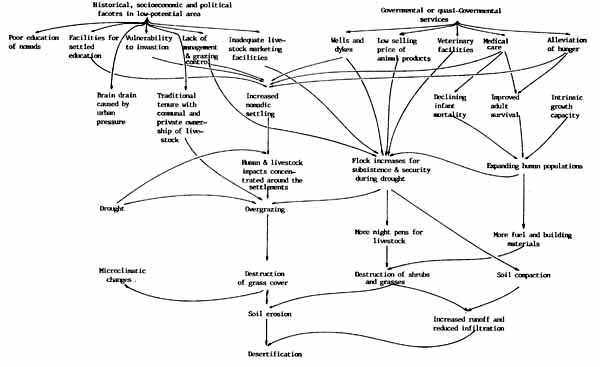

Figure 3.1 is taken from Burley (1982) and clearly shows the factors responsible for desertification in the North of Kenya; it is also broadly applicable to regions and countries with extensive arid and semi-arid areas where livestock grazing is predominant.

We can conclude this section on problem areas with the observation that there is an urgent need at world, regional and local level to take action in areas where there is heavy population pressure, where the land tenure system encourages inappropriate use of natural resources, and in arid and semi-arid areas where grazing and fuelwood consumption have exacerbated desertification.

From the above description it is clear that these situations reduce the return on peasant activities and cause high economic costs from natural resources degradation. It therefore becomes essential to promote natural resource rehabilitation and conservation plans and projects encompassing both the land and the local community.

Since inappropriate use of renewable natural resources reduces the potential profitability of individual actions and increases social costs, it is plainly worthwhile promoting involvement in rehabilitation and conservation programmes; as well as helping to increase individual incomes they also have considerable economic benefits which justify the application of incentive systems targeted at promoting community involvement.

Both natural resource conservation and rehabilitation projects and reforestation projects have considerable and attractive potential to feed local communities, particularly the following aspects (Finol, 1978):

- Shifting cultivation contingent upon a long enough fallow period

- All types of agriculture, such as agro-silviculture and forest agriculture

- Livestock - forest production

- Fodder production and shelterbelts

- Fodder production and protection woodlots

- Timber and fruit production

- Association of resins, pasture and timber

- Association of fibres, pasture and timber

- Association of resins, fruits and pasture.

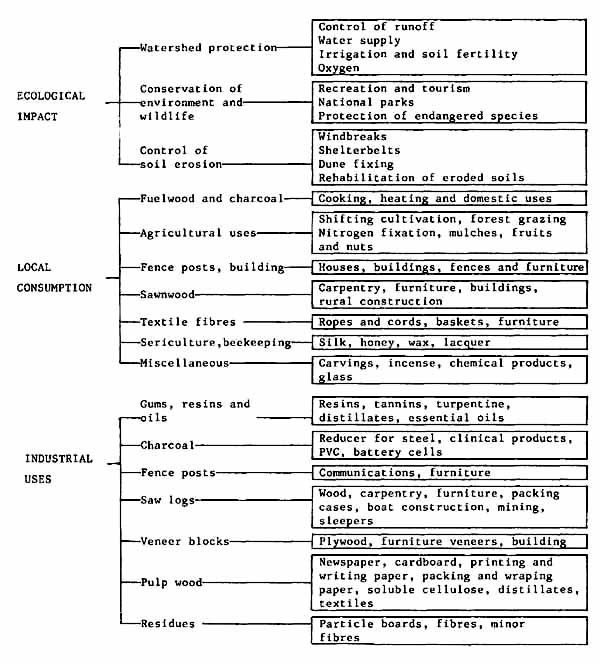

An example of this type of association is given in Figure 3.2 which provides a conceptual model of a Nepalese hill farm production system (Spears, 1978). It illustrates an integrated system utilizing all the various resources available in a specific rural area. As regards forest resources in particular, Figure 3.3 gives a schematic illustration of the role of forests (World Bank, 1978), whilst Table 3.1 points out the advantages of forestry activities for rural communities (McGaughey, Thorbecke, 1981).

The impact of the projects described in this Guide on land and labour is usually fairly clear:

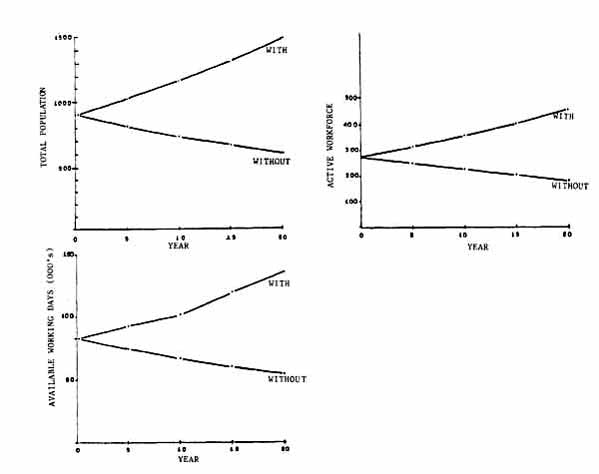

- Land: Usually less land is cropped and land use matches carrying capacity better since it is visibly imperative to farm more intensively, increase yields and protect the land. Figure 3.4 illustrates two types of land use in a specific situation - one with a project and one without (CONARE, USB, 1981). It can be seen that the need for arable land is reduced once shifting cultivation is eliminated and fallow or stubble is turned into thicket or forest - all in accordance with conservationist principles.

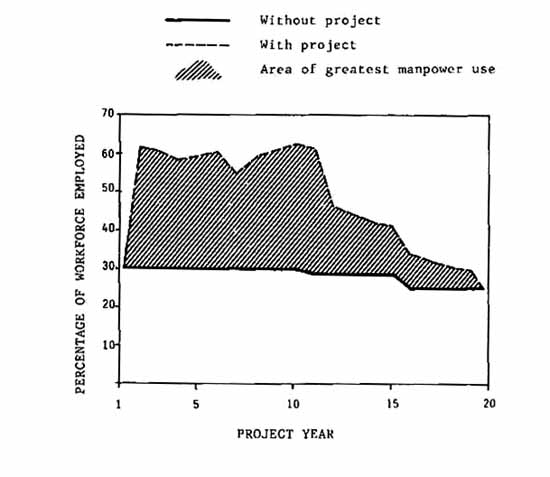

- Labour: Mountain watershed conservation projects have a twofold effect on labour. As a rule, emigration diminishes or even stops altogether; a downward population trend may even be reversed, leading to an increase in the size of the workforce and the number of days it is available for work. (Figure 3.5). The other main effect of having an integrated project is that more manpower is put to productive use; this can be seen from the example illustrated in Figure 3.6, where much more use was made of available manpower in the local community during the first ten years. It should also be mentioned that the work generated is normally for unskilled labour, providing a temporary complement to all the various integrated rural development activities (Adeyoju, 1978).

A community development project should have an integrated structure; this may involve a number of changes to the crop mix, both prior to and during implementation. The area given over to traditional crops, for example, maize, wheat and beans, is reduced to make way for more intensive crops (Comerma, et al, 1971). This is a logical step since traditional crops are unprofitable (although they cannot always be replaced altogether as they form part of the community's culture) and conservation works facilitate the introduction of more lucrative crops.

In addition, physical stabilization of crops follows the introduction of more intensive cultivation systems and techniques to boost profitability (FAO, 1980); mainly through improved soil utilization, and the use of improved seeds, fertilizers and biocides.

In some cases yield and output increases are impressive, as much as fourfold (FAO, 1981). Wheat yields in Cyprus increased by a factor of 1.4 to 2.6, whilst in Turkey fodder crop yields doubled and milk production quintupled; up to seven harvests a year were produced in El Salvador, cassava and banana production increased three to four times in Jamaica, whilst replacing wheat and maize by fruit trees in Pakistan raised the cash value of the crop twenty to thirty times (FAO/WFP, 1984).

Community development and conservation projects tend to be geared to multiple use of natural resources within the project area to take advantage of each site's potential; projects also try to encourage household and community units to produce different crops and outputs as well as to undertake other productive activities not involving land use (FAO, 1980) (Hidalgo, 1978).

Diversifying production is important not only because it helps communities to be more self-sufficient in basic commodities, but also because it makes them less vulnerable to market influctuations than if they practised single cropping.

(Source: Spears, 1978)

| PRODUCT | CHARACTERISTICS OF BENEFIT |

| Fuelwood | Low utilization cost Can be locally produced for little monetary outlay Replaces expensive commercial fuels Replaces farm residues Prevents destruction of protective cover Prevents scattering of workforce Ensures possibility of cooking food |

| Building materials | Low utilization cost Can be locally produced for little monetary outlay Replaces expensive commercial materials Maintains or improves housing standards |

| Feed, fodder and

grazing |

Protection of arable land from wind and water erosion Supplementary source of feed, fodder and grazing land Potential for supplementary feed production Increased productivity of marginal crop land |

| Marketable produce | Increased peasant and community incomes Diversification of local economy Additional employment |

| Raw materials | Inputs for local crafts, housing and small industries Increased profits from marketable produce |

SOURCE: McGaughey and Thorbecke, 1981

(Source: World Bank, 1978)

SOURCE: CONARE, USB, 1981

The first Korean ten year Forest Development Plan (inspired by the Saemaul Undong - New Community Movement) provides some important examples of production diversification (FAO/SIDA, 1983). Village activities included: sugar cane, wood and fruit and nut production, forest and fruit tree nurseries, oak mushrooms, pine mushrooms, kuzu bark wallpaper, cork bark, resins, chest nuts and artisanal stone carvings. PRIDECU in Colombia provides another example with integrated watershed conservation and communal reforestation projects leading to the production of timber, fuelwood, charcoal, fence posts and telegraph poles, fodder and traditional and new agricultural products, not to mention fish-farming and animal nurseries (MEDINA, 1983).

If mountain watershed conservation and reforestation plans and projects help boost production and employment in the area, individual and household incomes ought to rise significantly as a result. Although the costs of advanced cultivation techniques (fertilizers, improved seeds, more lucrative but dearer crops, herbicides, insecticides, fungicides, etc.) and conservation works (bench and orchard terraces, infiltration ditches, clearing stones, etc.) are fairly high, there should hopefully be more than enough extra income to cover them (Comerma, 1971) (FAO/WFP, 1984) (FAO, 1980) (Gallegos, 1978). Projects also try to match up community's agriculture, forest, livestock and artisanal work schedules in order to maximize employment and provide steady incomes (Fontaine, 1978).

Analysing a project from the daily wages angle (basic pay plus net earnings from work) gives the following result (de Camino, 1979):

| Minimum farm wage | 4 | Monetary units/day |

| Wages without project | 2.68 | Monetary units/day |

| Wages with project, Year 1 | 2.63 | Monetary units/day |

| Wages with project, Year 10 | 6.99 | Monetary units/day |

| Wages with project, Year 20 | 10.84 | Monetary units/day |

Although peasants initially fall short of the legal minimum farm wage, their earnings are guaranteed to increase throughout the life of the project.

Moreover, Table 3.2 (CONARE/USB, 1981), shows that earnings under a project, whether in cash or in kind, can substantially exceed those obtainable without it by anything between 37 and 73 percent.

Mountain watershed conservation and reforestation projects have proved themselves both

financially and economically viable. Project managers, though highly professional and

technically efficient, have been rather afraid of their projects coming under financial

and economic scrunity in the belief that they could not compete with other projects due to

the limited nature of the resources available to them. Table 3.3 provides examples of

forest projects targeted at upland communities and small owners showing them to have a

perfectly acceptable internal rate of return of between 11 and 22 percent.

In the Cocorotico and El Tejar watershed project in Venezuela, the internal (financial)

rate of return was 32.75 percent and the economic rate of return estimated to be 81.97

percent, showing that the project was profitable for individual peasants and much more so

for society as a whole once the benefits reaped from project conservation measures were

taken into account (CONARE, USB, 1981).

| YEAR | EARNINGS With Project |

TOTAL IN Bs.* With Project |

RATIO WITH/WITHOUT |

| 1 | 1.800.200 | 2.983.680 | 1.66 |

| 5 | 1.854.880 | 3.206.760 | 1.73 |

| 10 | 1.925.640 | 2.880.240 | 1.49 |

| 15 | 1.998.000 | 2.850.000 | 1.43 |

| 20 | 2.075.360 | 2.850.000 | 1.37 |

SOURCE: CONARE, USB, 1981 * Bolivares

| COUNTRY | AVERAGE FARM SIZE (Ha) | SPECIES | ROTATION | END PRODUCT | INITIAL COST OF INVESTMENT (US$/Ha) | FINANCIAL RATE OF RETURN FOR FARMER |

| Brazil | 20 | Eucalyptus spp. | 22 | Pulp, fencing, fence posts, fuelwood (15 years) and sawnwood (22 years) | 350 | 13% |

| Philippines | 10 | Albizzia falcata | 8 | Pulp (7 years) | 180 | 22% |

| Philippines | 5 | Leucaena | ||||

| Finland | 30 | Pinus sylvestris | 75 | Pulp, sawnwood, | 1370 | 11% |

| Picea abies | Fuelwood | |||||

| Colombia | 2 | Eucalyptus | 10 | Fuelwood | 150 | 16% |

| Sawnwood | ||||||

| Korea | 11 | Robina peudoacacia Alnus Lespediza spp. | 5 | Fuelwood | 250 | 18% |

| Sudan | 25 | Acacia Senegal | 5 | Gum Arabic | 50 | 15% |

SOURCE: Spears, 1978

Mountain watershed conservation and reforestation projects generally succeed in checking, reducing and sometimes eliminating the direct and indirect effects of abuse. In addition, they have many economic advantages which benefit society as a whole.

These numerous indirect benefits include: (FAO/SIDA, 1980) (FAO, 1981) (Atmosoedaryo, 1978) (Gregersen, Brooks, 1978) (Gallegos, 1978)

- Neutralization of the effects of erosion and degradation on water and soil resources, and checking the decline in arable land area.

- Temporary easing of pressure on land through more intensive techniques and optimal use of natural resources.

- Averting flood damage and health problems arising from contaminated water.

- Avoidance of damage caused by the drop in land and water productivity.

- Avoidance of damage resulting from impaired river navigability and the reduction in the useful life of reservoirs and hydroelectric plants.

- Reduction in flood prevention costs.

- Reduction in the cost of treating water for drinking.

- Reduction in reservoir dredging and power station maintenance costs.

- Conservation of important genetic resources.

To sum up, integrated reforestation and resource conservation projects are real economic and social development projects in terms of impact, frequently promoting community development by encouraging a shift towards more stable and less destructive activities.

For example, one effect of diversification and technological change is to increase the skills of the local workforce.(FAO/SIDA, 1980).

Under these projects, peasants not only tackle individual tasks themselves, but act together to solve common problems concerning health, food, education, communications, marketing and recreation - all things which help promote integrated rural development.

As already mentioned, manpower training can also be improved under integrated conditions. These advantages mean that the population is much more likely to set up cooperatives or other types of organization, either on its own initiative or in response to suggestions (Flinta, 1983) (Gallegos, 1978) (FAO/SIDA, 1980).

Reference has already been made to Korea and the important example it provides of the effects of conservation and forestry development projects on rural development (FAO/SIDA, 1983). Communities in Korea have been organized at local, regional and national level, with tasks directly related to resource rehabilitation and conservation being carried out at the same time as community oriented work, often of a voluntary nature: rural road building and improvement, bridge construction, construction of dykes and irrigation ditches, reservoir repair, bench terracing, streamed protection, drinking water supply systems, building of community social and work centres, warehouse construction, community work centres, collective manure heaps, village laundries, septic tanks, drainage systems, construction of community barns, public baths, rural factories and housing. In the case of PRIDECU, in Colombia, the community is the basis for the construction of all vital facilities and services, such as housing, health and education.

As can be seen, conservation projects in rural communities have so many important benefits that it is well worth trying to overcome any obstacles that might arise. It is not the aim of this Guide to expand on these benefits, since the subject is fully dealt within other FAO publications, such as Conservation Guide No. 8 on the participation of mountain communities in upland watershed management (Bochet, 1983) or Forestry paper No. 7 on forestry for local community development (FAO, 1978).

Incentives provide a policy tool for overcoming the major constraints on peasant involvement in conservation and reforestation plans and projects.