The aim of this chapter is to give a sound grounding in the various types of incentive classified below. The nature of each type of incentive is described and practical examples provided in line with the Guide's objectives. The link between goals and incentives is also discussed.

A satisfactory definition of an incentive has already been given in Chapter 2: "any inducement on the part of the State which will allow the peasant to absorb additional investments and gradually substitute income because of the works he has to carry out on his farm, to change the traditional methods with techniques and methods which will ensure the sustained yield of renewable natural resources within his farm and in its area of influence which will also contribute to the latter Is higher productivity"( see 2. 2.3.1.)

It is assumed that an incentive always has some economic and financial impact so no distinction will be made here between economic incentives and those of any other kind; after all, how this impact is perceived depends on who performs the analysis - the individual/community or the State/society.

Incentives are a macroeconomic and/or sectorial policy tool and can be applied to various monetary, fiscal, foreign trade, foreign investment, consumption, labour, or natural resource matters (McGaughey, Thorbecke, 1981).

Some of the main elements justifying the use of incentives to encourage community involvement in reforestation and conservation plans and projects are given below:

- The advantages of reforestation and conservation programmes have already been outlined; they can provide significant economic advantages for countries and regions particularly where the participation of rural communities is involved. Incentives are clearly worthwhile if they can stimulate this involvement at a lower economic cost than that of the economic benefits received.

- The advantages of diversifying the rural economy justify the use of a broad gamut of incentives. On occasions, it is the communities themselves who call for diversification. For example, however valuable and useful timber may be as a commodity, it does not necessarily underpin each and every forest production system. Some societies need help to develop their forests for purposes which have very little to do with wood production - fuel, honey, beeswax, silkworms, chewing-gum, handicraft fibres, gum collection, mushrooms, resins, food, fodder, dyes, extracts, etc. It is quite common, particularly in tropical forests, for all these minor products to make up the bulk of production, so that the community life is very dependent on the forest (Adeyoju, 1978).

- Depending on how incentives are applied, a whole series of important objectives can be achieved: engaging the community on conservation works on its own land, stimulating production through higher yields, making up financial losses arising from production cutbacks during conservation works, compensating for restrictions against certain crops which are inappropriate for the site, ensuring peasants receive a minimum wage until permanent crops establish themselves or new structures are operational, not to mention diversifying economic activities, remunerating community members who agree to take an active part in a plan or project, stimulating production of certain goods and services, extending community activities and furthering community development (social infrastructure, teaching, training, improved food, medical care, cultural activities, etc.) (Bochet, 1983) (Flinta, 1983).

- Incentives provide a policy tool for overcoming the major constraints to peasant involvement in reforestation and conservation plans and projects; such constraints include lack of awareness of the benefits of such plans and projects, lack of interest in participating due to limited financial appeal, lack of financial and technical capacity, legal difficulties arising from land use problems, and shortcomings in service and marketing infrastructures (Gregerson, 1978).

An analysis will be provided for each incentive of the effect of a certain number of variables having an important role in motivating communities to undertake rehabilitation and conservation actions under a specific plan or project.

The effects of an incentive, or rather of an incentive scheme or package, on securing peasant participation, may be expressed as a function of a number of variables:

EI = f (I, CL, O, M, Cn, T, D, R)

where:

EI = Effect of incentive or incentive scheme

I = Initial situation of target community as regards both natural resources

and significant sociological aspects

CL = Class or category of incentive(s)

0 = Main objective of the incentive or incentive scheme envisaged

M = Motivation of community

Cn = Constraint which the incentive is intended to remove

T = Effect of time on the incentive

D = Method of distributing the incentive to the community

R = Method of recovering the incentive.

There are independent variables which are in turn interdependent, although it is extremely difficult to isolate these linkages.

Many other variables could probably be defined as well, although the main ones are those listed above (Gregerson, 1978) (Botero, 1984) (McGaughey, Thorbecke, 1981) (FAO/SlDA, 1980) (Bochet, 1983) (Hidalgo, 1981) (Flinta, 1983).

Variable "I" (the initial situation of the community to which an incentive or incentive scheme is to be applied) refers in particular to the community's level of socio-economic development. According to du Saussay (1983), incentives should be designed as temporary policies bridging the gap between destitution and relative prosperity - the two initial boundary situations. The effect of an incentive and of community involvement in a plan or project will be very different in a primitive rural society with a low income and poor cultural level, than in a community of smallholders with larger incomes and a higher cultural level. A crucial factor here will be the extent to which the population is or can be organized, and any experience they may have of conservation and reforestation plans and projects (Adeyoju, 1978) (Botero, 1984).

The "CL" variable, or incentive class, will be discussed in more detail later, it being enough to say here that there is a strong connection not only with the impact of the incentive, but also with the community's initial general situation. For example, in a poor and disorganized community it is obvious that short-term bank loans would not only be inappropriate but quite impracticable as well.

Variable "O" (objective) is a trickier matter. An upland reforestation and conservation programme can have many possible objectives. As reference has has already been made to incentive packages, it is probably more appropriate to talk about a package of objectives, containing one or more of the following elements: soil conservation, rehabilitation of degraded resources, protection of farm land and downstream works, income redistribution, commodity production (e.g. fuelwood), industrial timber produc tion, increased productivity, increased output, diversification, etc. (Bochet, 1983) (Gregersen, 1978) (Diaz, 1976) (Flinta, 1983). There is undoubtedly a direct correlation between a community's initial situation (I), the class of incentive (CL), and the final objective of the plan or project. In the following analysis of the variable "O", the emphasis will be on the objectives of the incentive and not on the plan or project objectives which have already been fully discussed.

The "M" variable, or degree of motivation, has an enormous influence on the success of incentive packages in reforestation and conservation plans or projects. It will be shown later on that a plan or project usually requires some kind of promotion campaign to arouse sufficient interest before any concrete measures can be implemented.

However, the time it takes to motivate a group of individuals or a community will depend to a great extent on its initial situation (the "I" variable).

The variable "Cn" refers to the constraints on implementing the plan or

project. Gregersen (1978) has identified several types: lack of awareness of the benefits,

lack of interest, and inability re take the necessary action. Additions to this list might

include rights which have not been granted and lack of fair access to the market

(Government of Mexico, 1979).

The obstacle posed by an unawareness of the benefits of a plan or project depends to a

considerable extent on the initial level of development (I) of the group of individuals or

community, and can be overcome by greater motivation (M).

Lack of interest may be due to individuals not considering it worth their while, financially or otherwise, to participate; the class of incentive will play a crucial role here (CL).

The inability to take the necessary action can stand in the way of measures that would benefit the individual or community; financial and/or technical reasons may be the cause. Much will depend here on the class of incentive (CL).

The lack of rights issue may arise when an individual or community wishes to participate in a plan or project but is unable to because it has no legal right to occupy the land; such situations will need clarifying if the obstacle is to be overcome. In this connection, the community's initial situation (I) will be directly affected by whether or not land rights exist. The lack of such rights may be classed as a risk factor.

The lack of fair access to the market. This is frequently the case for the poorest and least organized individuals and/or communities. Small and inaccessible communities often have to depend on unscrupulous middlemen who, although they take no part in the hardest stage of the production process, emerge as the chief beneficiaries and therefore have little to gain by giving a fair deal.

The variable "T" affects the impact of incentives in two ways: the time it

takes to apply the incentive and (where relevant) the time it takes to recover it (Botero,

c.p. 1984) (Harley, Smith, 1976) (FAO/SIDA, 1980). The former mainly concerns assistance

of a temporary nature, the duration of which will largely depend on the community's stage

of development. In poor communities where natural resources are seriously degraded, this

period may be comparatively long; for refundable incentives, such as loans, it will depend

on when the investment matures and on whether there are any financial constraints.

Variable "D" relates to how the State delivers the incentive to the community

i.e. whether to the individual or to a community organization. As this affects the

incentive's impact, the choice will depend on the community's initial stage of development

(I), the objectives pursued (O), and the degree of motivation (M).

The variable "R" refers to the incentive recovery; this depends on the initial

situation (I), the kind of incentive (CL) and any constraints facing the community (Cn).

The incentive may take the form of an outright grant or be channelled back into the

community via a revolving fund, or revert to the government to be invested in general

funds or in special renewable natural resources development funds.

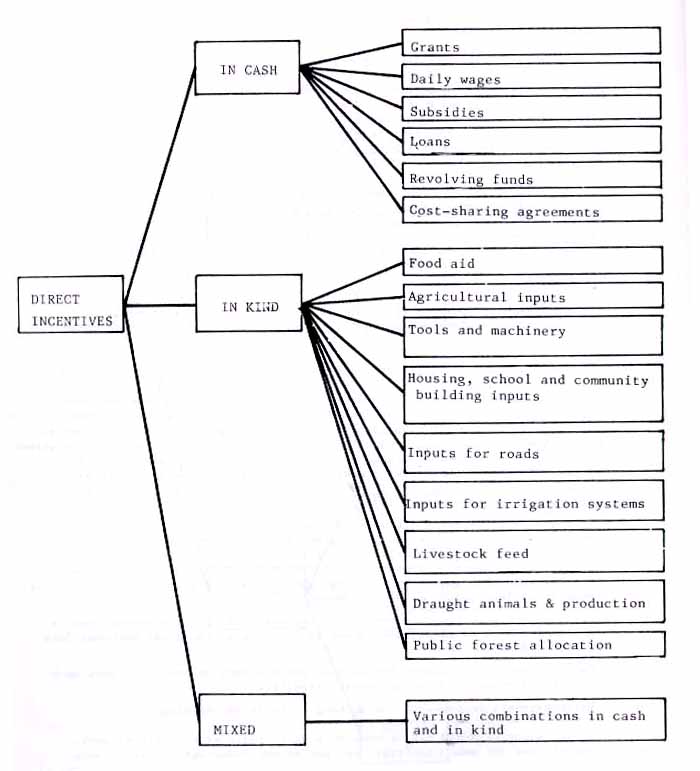

Figure 4.1 provides a rough classification of incentive categories.

Direct incentives are those given directly to the peasant or to the community in exchange for specific practical soil and water conservation (or reforestation) work (Hidalgo, 1981) (Gregersen, 1978) (Botero, 1984) (Flinta, 1983). The effects on individuals and communities are usually immediate (Flinta, 1983). Indirect incentives usually involve laws and regulations designed to benefit individuals and communities involved in conservation plans and projects (Hidalgo, 1981) or they may take the form of annual programmes run by the relevant state bodies designed to help achieve the objectives of reforestation and conservation plans and projects.

Each of these two categories contains a number of incentives which have been or are being applied with varying degrees of success in upland community reforestation and conservation plans and projects. It is often difficult to tell the difference between a direct and in indirect incentive since some actions are a mixture of the two. For example, a loan is a a direct incentive, but the terms under which it is granted are regulated by fiscal policy and so its terms can be considered therefore an indirect incentive.

Direct incentives usually aim at an immediate impact on individuals and/or the community, either because they are given directly in cash or in kind, or because they clearly improve rural life very quickly (Flinta, 1983). As a rule, direct incentives allow peasants and the community to invest what is, in fact, their most plentiful resource - the number of unoccupied working days. As Figure 4.1 shows, direct incentives may be classified according to whether they are granted in cash, in kind or a combination of the two. Incentives are, however, frequently mixed, complicating classification.

Loans apart, direct incentives are a common feature of economically viable activities, although their long term nature means that it is often difficult to secure their financing on the regular capital market (FAO, 1984). Financing difficulties tend to expand the timely on action to counter natural resources degradation (Bochet, 1983). Figure 4.2 schematically illustrates the various types of direct incentive.

There are almost as many kinds of direct cash incentives as there are situations in countries and regions. However, Figure 4.2 lists those which are most frequently met with, such as grants, daily wages, subsidies, loans, revolving funds and cost-sharing agreements.

In 2.2.3.2., a grant -as described as a direct cash -benefit paid to individuals to help them through an emergency and is therefore strictly temporary and short - a definition which diverges considerably from that found in the literature and much country legislation. Grants, under analysis, prove to be direct cash paid to individuals in disaster-struck communities to help overcome the Emergency by performing the most urgent tasks it has produced. Grants can be given, for example, in f flood zones, or in areas of chronic unemployment, remunerating work with a provisional emergency wage until a wider-ranging plan of action or a specific project is developed to tackle the causes of the disaster.

As regards the variables defined in 4.1 above, a grant can be said to be effective in initial situations (I) characterized by extreme urgency and low income levels: its objective (O) is to ensure survival; the community requires no special motivation (M) since the emergency leaves them no alternative; the only real constraint (Cn) is the total lack of economic capacity. Grants should only be available very briefly (T) - a longer period would indicate failure to end the emergency. The distribution method (D) is geared to individuals and all monies are granted outright (Flinta, 1983).

This is often the first type of "incentive" applied before starting a conservation- project; indeed, a project and an incentive scheme often follows in the wake of a catastrophe and the initial grant. In China, for example, communities receive financial assistance following very bad harvests or disasters, in return for reforestation or other work (FAO, 1982).

Daily wages are paid by the State to individual peasants or members of community organizations in return for conservation, reforestation or other work.

There are several different types:

- Daily payments to peasants who work land belonging to the State or third parties. In Korea, for example, the incentive scheme used in the ten year reforestation plan involves peasants being paid for: pest control operations on State land; work in nurseries run by the Government, Federation of Forestry Association Unions, or private individuals; reforestation of private land (together with other incentives), (Bong Won Ahn, 1978). The same system is employed in Jamaica (FAO/SIDA, 1980) and is, in fact, fairly widespread (Botero, 1979).

- In Korea daily payments are made to communities for erosion control works on different types of property (Bong Won Ah, 1978), whilst in China communities are paid for days spent setting up forest nurseries (FAO, 1982). In Colombia, communities under the PRIDECU project can build up working capital from cash grants by planting community woodlots and doing maintenance work (FAO/SIDA, 1980).

- Daily payments to peasants previously registered as being underemployed in return for work on farms when labour is short, e.g. the Nepal Manpower Bank (Botero, 1984).

- Daily payments to peasants for work on private land on condition they were previously unemployed, as in Denmark (FAO/SF).

- Daily payments to peasants for working on their own holding.

The above payments may be made on a daily basis or per unit of work. Daily payments are not usually advisable as they do not encourage people to work efficiently. They are best made at the beginning of the project when experience of using labour on specific jobs is lacking (FAO, 1980).

Analysis of this type f incentive in the light of the proposed variables shows that:

payments for work are normally made to communities whose initial stage (I) of development is highly precarious, particularly when peasants are paid for working on their own holdings; in more developed and more organized communities, payments are made direct to the community organization. In the former case, payments may not be effective in ensuring the continuity of community development and conservation actions since they are spent on consumption rather than being capitalized. In the latter case, the community body sets up a fund which is then invested in community infrastructural works.

As regards the incentive's objectives (O), direct cash payments for work performed may be used to promote conservation activities, particularly on land owned by third parties, since a peasant might be expected to work voluntarily on his own land. The payment acts as an incentive in that it compensates the individual for loss of time which he could have spent on other activities or for the period during which he cannot produce on his own land (until, that is, a particular job is completed or a new crop becomes productive).

Community motivation (M) is an important element, particularly since the wage paid is usually somewhat lower than the rural minimum wage. Motivation is crucial, since the peasant and the community should not look at the cash as payment for work, but as a contribution to improving social and productive infrastructure. This type of incentive is targeted at eliminating constraints (Cn), such as the economic impossibility of making improvements on individual holdings or community land. Payments may be made to individuals in the short term and to communities in the long term (T) under an established conservation support system, although some voluntary work should be going on at the same time. in Korea, work undertaken included: fire prevention, communal forest plantations and prevention and control of illegal logging (Bong Won Ahn, 1978) (FAO/SIDA, 1983). This combination of paid and voluntary work can sustain a long term effort without undermining the sense of community and association. The daily wage incentive can be distributed (D) by the State either directly to the individual, or to the community organization which in turn delivers it to the peasants. Where the community is sufficiently well developed, the latter is the most appropriate method as it increases the organization's authority, being much more tangible and direct than the State. Monies are not directly recoverable (R), except to the extent that the project in which they are invested produce economic benefits.

As defined in 2.2.3.3. a subsidy is a sum of money granted to a body or individual by the State to encourage works in the public interest. However, this meaning has incorrectly been ascribed by many laws and institutions to the word grant. A subsidy is the outright provision of financial assistance by the State and is not directly recoverable.

Subsidies are usually employed where financing is unavailable for works of long duration that require relatively high levels of investment such as terraces and plantations. Subsidies can cover all or part of the cost (Gregersen, 1978), or they may aim to encourage investment in forest plantations or conservation infrastructure.

Subsidies are linked to standard costs - the implication being that there should be some return. An owner or community that works more efficiently at lower cost may even increase the percentage of the costs covered by the subsidy (FAO, 1978) (Gregersen, 1978) (Bombin, 1975).

Assume standard reforestation costs of 800 m.u./ha.

Cost of 80 percent subsidy 640 m.u./ha.

With peasants/community planting at a cost of 700 m.u./ha, the real subsidy will cover 91 percent of the cost.

A subsidy is in fact a capital grant (of up to 100 percent) based on reforestation and conservation works tables or standards, although the recipient has to follow certain guidelines and be willing to accept supervision from the respective State body (Bombin, 1975). Subsidies may also be granted for not doing something. For example, restricting grazing to allow natural regrowth (Michaelsen, 1983).

In some cases (e.g. France), interest on loans for forest activities with no immediate return is subsidized by the State, thus reducing the cost of the loan and encouraging investments which would otherwise not be economically feasible.

Table 4.1 describes some subsidies for forest and conservation plans and projects. Most of them apply to forest programmes in developed countries. The reason for this is simple: a programme of subsidies involves State expenditure, which many developing countries are not in a position to sustain.

Analysis of this type of incentive in the light of the main variables is revealing:

The community should already have reached a certain level of development and sense of

responsibility (I) in order to carry out subsidized tasks. The objective (O) of the

incentive is to provide capital for investment in conservationist and infrastructures

whose efforts will only be felt in the long term. Community motivation (M) is essential

for programme success.

Since a programme of this kind has a cost, there has to be some input from the community

if administration and subsidy costs are not to exceed the economic benefits obtainable,

otherwise the incentive will fail in its purpose.

The subsidy is meant to remove the constraint (Cn) imposed by financially weak individuals or communities. However long the subsidy period decided upon, a definite limit should be set to it (T). For example, a reforestation subsidy should enable a specific number of woodlots to be planted before it runs out, whilst in conservation works the subsidy should enable essential terracing to be completed so that an individual or the community can move on to the next development stage where other policies or incentives are more appropriate.

The subsidy may be delivered (D) either to the individual or to the community and before or after the particular task has been completed. Subsidies themselves are non-recoverable (R) although a return is expected in the form of the project's potential economic benefits. In some cases, Venezuela for example, there is an initial recovery cycle in which the subsidy has to be reinvested by the community (in this case in farm infrastructures).

A loan involves surrendering the use of a certain amount of capital to a borrower for a limited period at the end of which it must be returned to its owner, together with a payment for its use. This payment, or interest rate, is expressed as a percentage of the total per unit of time. A loan is composed of a number of elements:

- The principal or amount borrowed

- The rate of interest, or the cost of the capital per unit of time

- The grace period, or the gap between receipt of the loan and the first repayment installment

- The amortization period, or number of years over which the loan is repaid.

This temporary surrender of the use of capital involves a number of elements which can

be adjusted, within the framework of a country's monetary policy, to encourage individuals

and/or communities to undertake conservation and reforestation programmes.

| COUNTRY | AREA OF APPLICATION | PERCENTAGE OF COST COVERED |

CONDITIONS | SOURCE |

| Venezuela | Conserve ionist infrastructure: stone walls, bench ing, individual terraces, holediggings, canals, water storage tanks, planting of forest and fruit species etc. Valid at project level | 100% of cost according to official tables | Community organized in committees with reinvestment of subsidy in social and productive infrastructure | Comerma, et al 1971 |

| Chile | Reforestation, plantation management, natural forest management. Valid at national level | Refund of 75% of costs according to official tables | At landowner's request | Republic of Chile D:L: 701 1980 |

| United States | Land preparation, planting, stand improvement. Valid at national level | 50-75% of costs | Small and medium sized farmers with minimum yield of 3 m³/ha/year | Risbrudt, et al, 1983 |

| Denmark | Reforestation | 50% of costs | Areas of less than 10 ha under permanent cover | FAO, S/F |

| Windbreaks and other areas. National level | 50% of costs | |||

| Finland | Reforestation, road construction, forest management. National | 20-70% of costs | At owner's | FAO. |

| Jamaica | Conservation practices: walls. National | 75% | Community work preferred | FAO/SIDA,1980 FAD, 1980 |

| Italy | Reforestation and improvement of de raded land | 75% of costs | At owner's | FAO, |

| Scrub to forest conversion. National level | 66% of costs | |||

| Holland | Afforestation and reforestation. National level | 80% of costs | Channelled through owners' | FAO. S/F |

| Spain | Reforestation and forest management National level | 50% of costs | At owner's request | FAO. S/F |

| Reforestation and forest management | 50% of costs | |||

| Switzerland | Reforestation, avalanche control, torrent control | Up to 95% | Amount depends on capacity of recipient. Community organization essential | FAO. S/F |

| Norway | Management plans Afforescation |

35-60% or 25-40% 75-80% |

Depending on whether State or individually run Treeless land |

Norwegian Forestry Society, 1976 |

| National roads and highways | 20-60% | Afforestation commitment required |

There are various types of loan which stimulate individuals or community involvement within an integrated rural development context:

- Short-term loans for financing harvests or short-cycle crops: these are also called bridging loans and provide sufficient working capital until after harvest. In Korea, for example, either the State, the village forestry assocation, or the purchasers put up the necessary funds so that complementary crops such as edible fungi and kuzu wallpaper fibre may be gathered - the harvest itself acts as security (Bong Won Ahn, 1978). The same thing happens in Mexico under the so-called Puebla Plan where industrial purchasers or the State provide interest-free credit to finance the logging of rough wood from concessions, with the loans being refunded from harvest proceeds (Government of Mexico, 1979). The Norwegian forest owners' association advances 40-50% of exploitation costs to its members (Norwegian Forestry Society, 1976). This type of loan is extremely useful since it focusses mainly on productive activities as part of an overall integrated community development plan (Flinta, 1983).

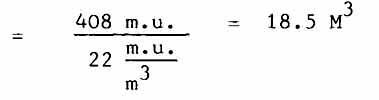

- Short-term loans in kind. This type of loan is calculated not on the basis of an amount of money but of a quantity of a certain product with payment often being made in kind as well.

Suppose that a community or individual requires an advance for cutting fuelwood:

Cost of cutting and transport 8 m.u./m³

Quantity to be harvested 50 m³

Labour (capital) requirements 400 m.u.

Duration of operation: three months

Annual interest rate of loan: 8 percent

Quarterly interest rate: 2 percent

Interest payable: 8 m.u.

Price of fuelwood: 22 m.u./m³

Equivalent of loan and interest in kind =

In other words , the peasant has 31.5 M³ of fuelwood at the end of the harvest for

consumption or marketing, having handed over 18.5 m³ to the community organization which

may keep some of it back in reserve and market the rest in town. Sometimes, applying very

short term rates of interest (as in the example) may not be appropriate e.g. when loans

are made in kind for planting forests. The advantage of the system is that the risk is

easier to picture so that the peasant is more prepared to accept it (Flinta, 1983). It is

common practice not only in agricultural credit, but also in renting farm land (annual

dues are paid in kind).

- Long-term loans on favourable terms. Long-term loans have to satisfy certain conditions, if they are to act as effective incentives in programmes targeted at reforestation, permanent crops, improvement to peasant or community infrastructure, etc. and particularly if they are to stimulate production without causing degradation.

- Low rates of interest

- Long grace periods during which no principal is repaid and interest accumulates until the harvest with which the loan will be repaid

- Long amortization periods

This type of loan is called a soft loan, to distinguish it from the short-term high interest bank loans (promissory notes) which are common currency in commerce. There is widespread agreement amongst authors that only soft loans can provide people with enough incentive to participate in reforestation or irrigation works, or in light farm mechanization using appropriate technology (Gregersen, 1978) (Botero, 1979, 1984) (FAO, 1980, 1984) (Bombin, 1975), (Michaelsen, 1983).

Table 4.2 gives a general idea of some of the main lines of credit used to support plans and projects for reforestation, permanent crops and productive conservationist infrastructure. From the table it can be seen that: I) loans are more common in developed countries ii) subsidies and loans are often combined iii) on occasions, a combination of subsidy, short-term bridging loan and long-term loan may also be used iv) lines of credit should be kept open i.e. the necessary funds should be made available. Diversification of lands permitting more integrated utilization of the resource and greater market security in project areas are another important aspect (Flinta, 1983).

This next section deals with the variables affecting the impact of loan incentives on community involvement in reforestation and conservation programmes. In the first place, the community's initial stage of social and economic development (I) needs to be fairly advanced. A degree of commitment and responsibility must already exist if the loan is to be made. As a rule, peasants and their communities all aspire to be self-sufficient in the long run, and view credit as being something intangible whose risks cannot be properly calculated. Short-term, pre-harvest credits in kind can prove useful here. In more developed and better organized communities, long-term loans may be effective particularly if production techniques have gone beyond the subsistence stage. The objective of the loan (O) is to overcome economic incapacity - one of the main constraints. Loans are made on an individual or collective basis if repayment is considered safe; this depends partly on the terms of the loan and partly on whether it is used in production, in increasing farm productivity, or in crop diversification. As regards motivation (M), peasants and communities often become disillusioned, either because the loan falls through because no money is available, or because of too much red tape (FAO, 1978); in the latter case, lines of credit are used scarcely, if at all. Regarding the constraints the incentive might remove (Cn), there are a number of important elements which all come into play. The loan should help resolve the problem of economic capacity, and provide capital for those who already possess land and labour. in return, the lender requires some form of guarantee; this can be furnished by arranging for the community itself to assume responsibility for the loan. Of course, loans should be combined with other incentives designed to remove other constraints. After all, if full use is to be made of loan facilities the peasant/community needs to be aware of the benefits of a plan or project and, more particularly, of the advantages of taking out a loan, hence the importance of motivation and training. The lack of rights(to land especially) is another constraint which can be overcome by combining a loan policy with the regularization of land titles and tenure. Fair access to the market may be won by putting the community in a position to market all peasant produce, obtain forward sales or supply contracts, or negotiate support prices.

The time variable (T) is directly affected by the grace period, the amortization period, and the interest rate - all aspects which determine whether or not a loan is advantageous. Distribution (D) may be on an individual or a community basis; if the former, some community support will still be needed. The loan itself is directly recoverable (R) - not only is it reimbursed, but a price is paid for use of the capital. The effect of inflation on the loan is a subject which will be dealt with later. lf the loan is a long-term one with no adjustment for inflation, it may turn into a partial long-term subsidy.

| COUNTRY | GENERAL CONDITIONS | SOURCE |

| Austria | Low interest loans for capital investment in forest farms | FAO S/F |

| Denmark | Soft loans with a three-year grace period, amortized over 10 years | FAO S/F |

| Finland | Soft loans for forest management, drainage works, reforestation of flooded zones, country road building, and fertilizers. One hundred percent of costs covered in conjunction with subsidies | FAO S/F |

| !Japan | Soft loans for managing planting and thinning operations | Tsuru, 1981 |

| France | Long-term loans to economically significant projects, at an annual | FAO S/F |

| interest rate of 0.25-1%, with a grace period of several years.Granted by the National Forestry Fund | ||

| :Italy | Loans for purchasing and reforesting former crop land in mountain areas, over 30 years and at subsidized interest rates | FAO S/F |

| Spain | Long-term, low interest loans for both private individuals and associations to carry out roadside reforestation, pasture establishment and improving forests. Up to 75% of costs covered with the help of subsidies | FAO S/F |

| Colombia | Loans for reforestation based on a standard cost per ha. 15 year duration with accumulated interest payable in the 8th, 12th and 15th years, at an annual rate of 15% plus 1% towards a technical assistance fund | INDERENA, 1981 |

A revolving fund is an important incentive in rural community development. Initial capital is provided by a State grant or loan, or by contributions from individual producers. The fund is used to make short term loans to peasants, to purchase inputs, and to hire labour for short cycle crops. The loan is repaid in cash or in kind at harvest time. (Hidalgo, 1981) (Botero, 1979) (FAO, 1980).

This type of fund is normally operated by the community organization. If properly run, it can strengthen the organization and increase its prestige among its members as a useful and efficient body.

Revolving funds can make different kinds of loans: for agricultural inputs, simple machinery, wages, household items, education, etc. If the revolving fund is to work properly its value should not decline as time goes by; money, therefore, should not be left idle but should be placed in accounts payable on demand, short-term deposits or investments which produce a reasonable return and increase the size of the fund. Whilst members of the community organization are entitled to take out loans with interest, they are also expected to contribute moderate amounts to boost the fund, e.g. on a monthly basis or as a minimum percentage of the crop.

The incentive effect of the revolving fund depends on a number of variables. The extent to which the community is organized (I) is an important factor, since there must be some form of cooperative, association, conservation committee or similar body if the scheme is to work. Not all projects start out with such an organization and consequently, do not have a revolving fund. This is a task which needs to be undertaken once the project is underway. The objective of the incentive (O) is to provide short-term finance for directly productive activities or the direct improvement of an individual's or household's situation in the community. A revolving fund certainly calls for motivation (M) and an organized community, but it is also a powerful incentive in itself in that it provides short-term benefits for the peasant. The incentive can also help lift all but the toughest economic constraints (Cn). The fund can lend direct to any member of the community meeting its requirements (D). The initial capital apart, loans made out of the revolving fund are recoverable in the short term if community fund managers are skillful, properly advised, adequately trained and well informed, so that they can protect the value of the fund and even increase it. FAO has experimented successfully with this type of fund in conservation projects in Thailand and El Salvador.

As its name indicates, a cost-sharing agreement brings together the owners of land, capital and labour for the purpose of undertaking conservation, rehabilitation and/or reforestation activities, on the basis of a contract establishing how the resulting benefits are to be shared out. Strictly, a costsharing agreement should not be classed as a direct cash incentive, since it usually consists of a parcel of measures.

Cost-sharing agreements take two main forms:

- The State undertake- all the work and provides all the resources, recovering its investment from farm production (FAO, 1980) (Botero, 1979, 1984).

- Resources are held in different hands - land by the owners, labour by the peasant, and capital by the State. Work is carried out on private property, with funds supplied by the State and labour by the peasants, the resulting product being shared out on the basis of each party's contribution.

Many examples of different resource and incentive combinations are available; Table 4.3 lists just some of them. Cost-sharing agreements are appropriate to reasonably large farms or to groups of small-holdings subject to land consolidation. The system need not be confined to reforestation; it can also be applied to silvo-pastoral or agro-forestry management, and to conservation works with active peasant involvement. One particular constraint is the timelag between implementation and exploitation although this can be got round by making advances against future production (FAO, 1980). Distribution of produce is another problem posed by this type of incentive since resource units (land in hectares and years, labour in days and capital in monetary units and years) are not comparable with one another. One solution is to value everything in monetary units and distribute on that basis.

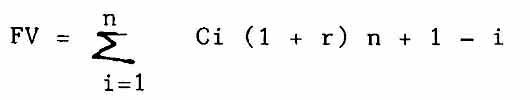

Assuming:

| - that the State, community and landowner join together to

plant one hectare with a forest species having a 12-year rotation cycle |

|

| - that the State provides inputs and technical assistance

to the value of 200 m.u. during the first year and 20 m.u. in each of the eleven subsequent years, amounting in total to |

M.U. 420 |

| - that the landowner provides land which might also be used for extensive livestock production. The land would provide a net return of 40 m.u./ha/year in livestock production, so the cost of a 12-year plantation would be | M.U. 480 |

| - that workers provide the equivalent of 500 m.u.of labour to establish the plantation and 40 m.u. for the remaining 11 years to maintain it, making a total of | M..U. 940 |

| M.U.1840 |

The product might be distributed in the following proportions:

State : Landowner : Community = 23 : 26 : 51

However, this would mean ignoring the value of annual contributions. It would be more logical to capitalize such contributions using the following formula:

Where:

FV = Future Value

Ci = Contribution in year i

r = interest rate

n = number of years in the rotation

In this case, the value of contributions capitalized at 10% (assuming this to be the market rate of e.g. certificates of deposit, savings accounts, etc.) would be:

| COUNTRY | ALLOCATION OF | |||||

| GOVERNMENT LANDOWNER WORKER CONSUMER | SOURCE PRODUCT | |||||

| Korea | Land | Community labour for reforestation | 90% community - for distribution amongst workers; 10% landowner | Bong Won Ahn, 1978 | ||

| Korea | State as land-owner rents land to community | Community labour for reforestation | 100% community with transfer of land if plantation is successful | Bong Won Ahn, 1978 | ||

| Colombia | INDERENA: Plants, fertilizers, insecticides, fungicides, technical assistance. Payment for each tree planted and for each live tree maintained |

Community land | Planting, maintenance, thinning, and logging, using community Labour | Product goes to community which pays the costs plus a pecentage for inflation, the total not to exceed 50%. of the product's value | FAO/ SIDA, 1980 | |

| Colombia | Fish and live stock rearing: Inderena supplies equipment, specimens and chemical products | Community labour | Fish and animal products (split 50-50) | FAO/SIDA, 1980 | ||

| China | Plants and inputs for reforestation along roads and farm boundaries | Manpower organized by communities |

70% community, 30% State |

FAO. 1982 | ||

| Phi I ippines | 15 year loan from Philippine Development Bank. 12% annual interest rate | land and at least 25% of manpower costs | Manpower | Pulp factor plants, technical assistance and first option to buy | State: recovery of loan Landowner: difference between proceeds and loan repayments Worker: wages Industrial Consumer: Es. product | Gregersen, Contreras, 1979 |

Government = 1035 M.U.

Landowner = 941 M.U.

Worker = 2389 M.U.

Total of Capitalized Contributions = 4361 M.U.

This would give the following proportions:

State : Landowner : Community = 24 : 22 : 54

Distribution on the basis of capitalized contributions is not only logical but to the community's advantage since peasants have more invested for a longer period. As a rule, communities receive the largest share, since reforestation and conservation works in depressed areas have to rely on simple, labor-intensive techniques.

A review of the impact of this type of incentive highlights the role of the main variables:

- The community's initial stage of development (I) should be fairly high, at least from the organizational standpoint since it will have to develop negotiating strength as well as provide manpower.

- As regards the incentive's objective (O), cost sharing agreements can be used to exploit available resources and build up capital whilst improving the environment at the same time.

- Both the community and landowners will need to be strongly motivated (M) since they will be making contributions with no prospect of short term benefits. This is a reason for having incentive packages, so that some benefits will be received straight away.

- The incentive should aim to remove constraints (Cn) such as ignorance of the benefits accruing to each of the parties - hence the importance of a clear information campaign beforehand. Such schemes also solve the financial and technical problems, since neither the landowner nor the community will have to bear the cost of obtaining loans and the State will provide the technical assistance. Furthermore, those who do not own land will be given access to some of its fruits.

- Time (T) is an important factor, and it should be clearly explained to the peasants that the investment will take a long time to mature. This is the reason for preferring an agreement with the community rather than with individual peasants. If, for whatever reason, a peasant ceases to belong to the community, the latter can compensate him for any labour he has provided.

- The incentive is widely distributed (D) as it favours both worker and owner in proportion to the value of their contributions.

- Finally, the means of recovery (R) should be perfectly clear and everyone's contribution capitalized accordingly.

Direct incentives in kind take the form of material goods which are delivered to peasants and/or communities for two main reasons: to allow them to work on renewable natural resource conservation and rehabilitation works or to provide them with the necessary means to improve production or community infrastructure and thus the individual and collective situation of the peasants (Michaelsen, 1983) (FAO/SIDA, 1980) (Hidalgo, 1981) (Flinta, 1983).

Incentives in kind have played a crucial role in prompting community involvement in almost all plans and projects, since they are usually applied with a specific purpose in mind and are that much more likely to achieve results.

This type of incentive can also be seen as "recognition of work undertaken on- or off-farm in accordance with an investment programme for transforming farm production conditions"(FAO, 1980).

Incentives in kind are not restricted to on-farm activities but can be extended to community or State land, or to social infrastructure works. As Table 4.2. shows, the main incentives in kind are: food, production inputs, small tools and equipment, inputs for community infrastructure, inputs for road construction, small irrigation systems, livestock feed, draught animals and production and transfer of public forests to the community.

There are other types as well, the above being only the most important.

Incentives in kind are usually most effective in poor communities because they are straightforward and meet immediate social and productive needs (FAO, 1978). The criterion for this type of grant should be productivity as it is for subsidies, thus reducing its cost for the Government (Gregersen, 1978).

With the exception of food (see below), variables affecting the impact of incentives in kind will be discussed under a separate heading and not under each incentive category as has been the case up till now.

A common incentive is to provide peasants with food in exchange for work. A food ration may remunerate work on their own land, on neighbors land, on communal land, or on works for the benefit of the community as a whole. The rations are intended to supplement the diet of the peasant and his family. It is an appropriate system in areas of seasonal unemployment or chronic underemployment (Botero,1979) (FAO, 1978, 1980).

Food can be delivered in various ways, depending on the particular situation of the plan or project:

- Food supplied in exchange for work on the peasant's own farm or on other farms according to the number of days worked. However, ,this takes no account of productivity and can prove expensive. It is mainly used for tasks whose output cannot be measured, such as forest patrols. Where output can be measured, this form of remuneration may be used initially until some idea is obtained of yield standards appropriate to the various activities. The system can also be used for community development works, e.g. construction of schools, clinics, etc.

- Rations may be based on productivity. This is the ideal form of remuneration since it can bring down programme costs quite considerably. The organizing body will need to establish norms for each type of activity. If the peasants take less time they still receive the rations and are thereby rewarded for their greater productivity.

- A differential system which takes both productivity and the beneficiary of the work into account. For example, although work undertaken on a peasant's own farm should be voluntary, he may be so poor that some of his work will have to be remunerated with food. Since work on community projects benefits the collectivity, the worker receives a larger portion of the food ration, although some work is still considered voluntary. When, however, work is carried out on land owned by a third party, it seems reasonable to reward this with the full food ration (FAO, 1980).

Assuming it is wished to construct one hectare of bench terracing on the basis of an average of 400 days work per hectare (Dongelmans, 1980):

Payments under the differential system would be:

a) 200 food rations on peasant's own farm

b) 300 food rations on school farm

c) 400 food rations on neighboring farm.

Plans with a food-for-work component among their incentives are based on joint agreements with international aid organizations and/or bilateral agreements with specific countries. The purpose of an agreement is to assist governments and countries which lack the means of implementing projects (Flinta, 1983) and are therefore unable to provide the initial motivation to channel surplus manpower towards conservation works and agricultural, livestock and forestry production activities.

The main exponent of food-for-work incentives is the World Food Programme (WFP), which has succeeded in implementing large scale, labour-intensive projects and encouraging heavy peasant, and particularly community, involvement in programmes of various kinds (FAO, 1980). Under WFP auspices, soil conservation and watershed management programmes totaling 463.7 million US dollars have been, or are being, developed in nineteen countries (FAO/WFP, 1984).

Other international bodies or national organizations also use food-forwork: Freedom from Hunger Campaign, Unicef, CARE, World Watch, OXFAM, Christian Aid, Bread for the World, Misereor, Norid, Food for the Hungry, Danchurchaid, Development and Peace, etc. (FAO, 1980).

In addition, the WFP is often a joint partner in FAO and UNDP training and technical assistance projects.

Donor organizations are usually fairly flexible about the use to which food is put. For example:

- The Government may receive the food and lower wages in accordance with the value of the ration. This releases resources for other activities or for extending the scope of the project, always assuming the funds are allocated for that purpose (FAO, 1980).

- The Government may receive the food and sell some of it on the market in order to provide a mixed incentive, part in cash and part in kind, assuming that peasants need at least some money to meet expenses (FAO/WFP, 1984).

- The Government may receive the food and sell some of it on the market in order to

obtain funds to cover food handling costs (storage, transport) or the project running

costs such as promotion, technical assistance, input procurement, etc.

Within each project, food-for-work incentives should form part of a broader package of

incentives if they are to be an effective tool (FAO/WFP), as in the case of Honduras (de

Camino, 1979), Ethiopia, Jordan and many other countries (FAO, 1983). Food-for-work

incentives have been introduced into China as well, with the Government supplying

communities with the extra basic grains they need, in exchange for forestry work

(Michaelsen, 1983) (FAO, 1982).

Food-for-work is an effective incentive measure, providing the following variables are taken into account:

- The community or society should usually be poor and at a fairly low stage of development (I). This incentive has a significant role in countries which do not have enough resources to provide generous subsidies or loans. Furthermore, a poor community can quickly be motivated if one of its basic needs - food - can be satisfied.

- The objective (0) of such an incentive may be to enable a government which is short of resources to initiate natural resource rehabilitation and conservation plans and projects and compensate the peasant for time spent on conservation works on his farm, on neighboring land or on State land, or for time spent on activities to benefit the community. Aid of this type also helps cover the period until the investment matures, by providing rations in return for maintenance work.

- Food distribution provides excellent motivation (M) to involve peasants in

conservation work, although it is best if the rural

poor have been organized in some way first. In any event, it is crucial not to give the

impression that food is in any way

a substitute for wages. In cases where this has happened, and where for example, poor

organization has delayed food deliveries, peasants have reacted as if deprived of their

wages, even going to the lengths of destroying the work they had done.

- The main constraint (Cn) is clearly the financial one, affecting the country's and the peasant's ability to undertake rehabilitation and conservation projects.

- The application period (T) should not be too prolonged, with the community's own crops providing the necessary continuity. The poorest communities will naturally receive assistance for a longer period.

- Food may be distributed (D) either directly to the peasant or, preferably, via the community in order to give local leaders responsibility and thus strengthen community organization.

- As regards recovery (R), the food is simply donated in the hope that it will trigger an ongoing conservation and production effort and that any social benefits from the project will filter through to society.

Agricultural inputs can be a major inducement in soil rehabilitation and conservation programmes. Peasants are usually only indirectly concerned by conservation programmes and then only when there is a food or fuelwood shortage. A conservationist infrastructure is of no use to them if the structure of production remains unchanged. The peasant needs to be able to improve production straight away; in addition to agricultural extension and training, therefore, peasants need to be told about the effects of improved inputs.

Those agricultural inputs most frequently used in reforestation and conservation programmes are:

- Forest plants for timber and fuelwood

- Perennial crop species, particularly fruit trees

- Saplings and seeds of fodder species

- Improved seeds (species, variety and genetic quality), and edible fungus mycelia

- Complete fertilizers

- Herbicides, fungicides, insecticides, and inoculate for biological control

- Fencing wire

- etc.

Supplying agricultural inputs was one of the chief tools in promoting community involvement in projects in Korea (Bong Won Ahn, 1978), Jamaica and Colombia (FAO/SIDA, 1980), Honduras (FAO, 1981), China (FAO, 1982), etc.

A good conservation project involves land consolidation, reduction of the area under crops, crop intensification, and increased output and productivity. This in turn means making a more intensive use of manpower as well as permitting the introduction of intermediate techniques. Moreover, in many cases peasants do not even have their own tools whilst those that are available may not be the most suitable (Flinta, 1983) (FAO/SIDA, 1974, 1980) (Michaelsen, 1983).

Supplying small tools maybe used as an incentive in two different ways:

- As a gift to the peasant or community to ensure that in the future peasants have at least the minimum equipment to continue with project activities

- As a loan whilst productive-conservationist infrastructure is being set up, particularly when there are a lot of bench terraces or plantations to be laid out and the tools will be used to achieve subsequent years' objectives.

These gifts or loans usually consist of traditional (though generally improved) tools, such as spades, picks, mattocks or weeding hoes, rakes, seed planters, etc. Machinery is usually light and can be operated by one person e.g. knapsack, mechanical or motorised sprayers, cultivators, and manual harvesters. Larger equipment, such as farm tractors, ploughs, and pumps, are sometimes supplied to communities.

Conservation and production are not the only concerns of an integrated rural development project. A rural population cannot be made stable just by providing work opportunities; services need to be made available as well. The cost of the necessary Infrastructure can be reduced by relying on the community for voluntary labour in exchange for food. With the State providing inputs and materials, the community can, with proper technical assistance, build schools, clinics, community centres, marketing areas, recreation facilities, as well as improving rural dwellings, etc., (Flinta, 1983) (FAO, 1978).

The most frequent inputs are corrugated roofing, bricks or cement blocks, cement, timber, piping, small electric generators, etc. With the help of these materials and-by involving the peasants directly in community works, people can be given a sense of pride and independence, and confidence in their ability to manage their own affairs and not to rely on the State for everything. As Adeyoju (1978) has pointed out, in many communities people prefer to work in groups rather than separately, and this type of work gives them the opportunity to do so.

A soil rehabilitation programme integrated with new production systems creates surpluses for marketing locally or in the nearest town. This means that approach roads will need to be built or improved so that they are passable throughout the year. The same applies to any small village road in the project area (Flinta, 1983) FAO. 1978).

If there is considerable surplus labour - and especially if there is a scheme for supplying food-for-work or inputs and machinery as well - the community can do much of the work on a voluntary basis.

The main tools and inputs are:

- Stone and sand to make roads passable throughout the year

- Cement and timber for gutters, drains and culverts

- Gunpowder, dynamite and flushes for rock blasting

- Spades, picks, levers, barrows, machetes and axes for clearing access roads.

Roads are often a controversial subject since erosion sets in quickly if they are not well built; incentives must, therefore, be matched by technical assistance and machinery.

Reducing the risk to crops is an important aspect of rural production systems. Traditional crops grown on hills under shifting cultivation are rainfed. Terraces and other conservation works not only call for greater diversification and improved inputs, but also absorb more money and labour per unit of area. It is therefore important to reduce risks to a minimum and make intensive use of these conservation works by trying to obtain as many harvests per year as possible, particularly in tropical and sub-tropical zones.

Small irrigation systems can make a significant contribution here, by supplying water at critical times and even make possible an additional harvest during the dry season.

There are various type of systems:

- One possibility is an extensive irrigation network in which the main water catchment works and pipelines are provided by the State and the secondary channels for farm irrigation are financed by peasants and their communities. In Venezuela, this system has been successfully applied in the highly productive Andean regions. (Hidalgo, 1981).

- Another method is to construct individual irrigation systems on a much smaller scale to exploit small streams. The peasant himself builds the reservoir and lays out the pipes whilst the executing body supplies the pipes, the joints, and the taps as well as technical assistance in grading and trace-cutting, as was done in Honduras (FAO, 1981).

Another type of incentive in kind is to provide peasants and/or communities with animals for two different purposes:

- Work or draught animals, such as oxen, horses,mules and donkeys, to supplement the resources of small rural farms and for use in ploughing and transport. This is particularly important in mountain watersheds where roads are poor and expensive to build.

- Production animals for integrated small farm development e.g. laying hens, fattening chickens, pairs of rabbits, small or large breeding stock in semi-permanent or permanent housing, fish fry for aquaculture, etc.

This type of incentive, particularly in the second case, needs to be backed up by technical assistance and extension work since peasants are not as a rule familiar with rearing techniques for some of these species. It is an area with plenty of scope for development, since it does not require a lot of space and agro-forestry residues can provide the necessary feed.

A number of programmes have adopted this form of assistance. One such is the PRIDECU project in Colombia, which provides communities with fish fry and animal rearing stock. (FAO/SIDA, 1980).

In some projects, production activities encompass livestock, poultry and fish. Not only does this require a considerable amount of technical assistance, it also calls for special feeds or concentrates. Feed rations act as an incentive in setting up and establishing breeding stock, e.g. rabbits, fattening poultry, laying hens, fish-farming, stabled livestock, etc. This type of assistance is just as important as improved crops, since it allows consistent high productivity, thus ensuring a cost effective farm.

Sometimes, communities may not have enough land to meet their fuelwood requirements, or people that wish to plant trees have no land on which to do SO. In other words, one of the factors of production (land) for developing the forest's protective and productive capacity is missing. Land or public forest has sometimes been allocated in these circumstances to communities or individuals to undertake forestry activities. Some examples:

- The Korean Government rents land to communities for tree planting under its ten-year reforestation plans. If the plantation is successful, ownership is transferred to the community. This is a powerful incentive ensuring that work is done properly. (Bong Won Ahn, 1978) (FAO/SIDA, 1983).

- Some examples from Latin America are described by Bombin (1975). In Guatemala, the

Government makes a free grant of deforested national land to any firm or individual

interested in establishing man-made forests; in Peru, small-scale plantations are given

free in order to stimulate awareness of the importance and advantages of trees, and

encourage peasants

and their communities to take practical action.

Communities should always be involved in forestry activities carried out on land thus received to motivate them and to teach them how to do the work themselves.

One variation is to have integrated demonstration plots combining conservation works, agricultural and forest crops, fruit trees and livestock and forestry development activities; once fully operational, these can then be gradually handed over to the community organization to provide peasants with a permanent managed example as an encouragement to persevere with programmes.

Direct incentives in kind all conform to a similar pattern, with the exception of food-for-work which operates on a completely different scale. The influence of variables on incentive impact is described below:

- Initially, the community is normally extremely poor and under developed (I). Both

peasants and the community urgently need

to be assisted in a way that produces immediate benefits. A project will often be severely

handicapped from the very

outset if the right inputs are not made available.

- The objective (O) of this type of incentive is to encourage the use of conservationist and productive infrastructure introduced by the project, together with higher-yielding and higher-value crops and products. This involves directly encouraging changes in traditional exploitation techniques, using systems and methods which preserve the soil and improve its fertility.

- Both the peasant and the community have to be highly motivated (M); this means that they must already be involved in the project and that a training and extension system geared to ensuring optimal use of inputs is fully operational.

- Incentives aim to lift constraints (Cn) such as lack of economic capacity (since incentives partly represent labour capital), and lack of technical capacity (since inputs represent technological improvements which, combined with technical assistance, help individuals and the community to transcend the subsistence economy).

- Direct incentives in kind should operate on a short- to medium-term basis (T). After a while, it is assumed that the community has overcome some of its constraints and new incentives are introduced such as loans or indirect incentives.

- Incentives in kind may be distributed (D) directly to peasants, to peasants via the community, or directly to the community, depending on the kind of incentive and its purpose.

- The incentive is normally non-recoverable, although it is of course hoped that the economic benefits of the plan or project will outweigh the cost of the incentives.

Plans and projects, however, do not rely exclusively on one direct or indirect

incentive, nor on just incentives in kind or cash incentives. A combination of incentives

is usually applied, some of them being mixed incentives.

A mixed direct incentive combines characteristics belonging to both incentives in cash and

incentives in kind; it can take innumerable forms depending on the situation.

Some examples of mixed direct incentives are:

- Food plus cash allowances

- Food plus daily wages

- Food plus daily wages and inputs

- Loans plus subsidies

- Loan and/or subsidy plus inputs

Most of these combinations can prove useful in cost sharing agreements where various types of incentives are employed. Mixed incentives provide the most realistic solution for overcoming constraints and attaining the objectives of specific plans or projects; in other words, they are tailored according to an initial critical diagnosis.

Indirect incentives are legal measures designed in line with a protectionism or development policy aimed at encouraging producers and communities to carry out mountain watershed rehabilitation and conservation works, reforestation, and integrated rural development activities. These measures are intended to generate resources for plans and projects without any direct budgetary appropriation; this can be done by the State taking the necessary legal and statutory steps to standardize the appropriate procedures, and, on occasions, by providing funds from the public purse.

Indirect incentives involve applying the instruments of monetary, fiscal, consumer, service, social, and natural resources policy etc. (McGaughey, Torbecke, 1981) to concrete problems affecting the development, conservation and rehabilitation of land and communities. (FAO/SIDA, 1981) (Michaelsen, 1983).

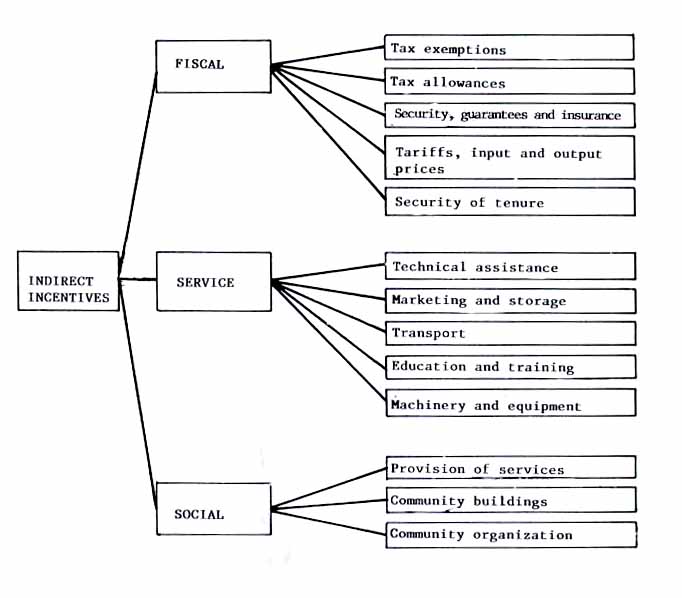

Figure 4.3 gives a tentative classification of indirect incentives drawn from the work of various authors (FAO/SIDA, 1980) (Hidalgo, 1981) (McGaughey, Torbecke, 1981) (Botero, c.e., 1984). For the purposes of this Guide, incentives fall into one of three categories: fiscal, service, and social.

Fiscal incentives are a legal and statutory means of channeling public (extra-budgetary) funds towards reforestation and conservation plans and projects, or of legally facilitating such projects.

As the diagram shows, fiscal incentives may involve: tax exemptions, tax allowances; security, guarantees and insurance: tariffs, input prices and output prices; security of land tenure.

Strictly, security of land tenure is not a fiscal measure, but one which governs the use and disposal of land and its products so that the land inheritance situation can be regularized, giving the farmer economic stability.

Generally speaking, fiscal policy is concerned with gathering income to meet public expenditure, complementing economic policy measures directed at investment, production and employment, and reducing individual and regional income differentials (Riihinen, 1981). Fiscal policy measures require careful handling and a flexible approach, otherwise target activities (such as forest reforestation and repopulation) will never be self-supporting and will owe their survival entirely to tax breaks (Haley, Smith, 1976).

Moreover, fiscal incentives do not by themselves have any impact on small rural producers, due to shortage of labour capital (FAO, 1980); a blunter way of putting it is that fiscal allowances are irrelevant where peasants are so poor that they fall outside the tax net anyway (du Saussay, 1983).

These involve citizens being partially or totally exempted from government taxes on their goods, income, or activities. In granting tax exemptions to promote a particular activity, care should be taken to target only those taxes where exemptions are most likely to help achieve the desired objective.

More specifically, exemptions to stimulate forestry and conservation activities have

variously focussed on land, investment, forests and forest products. Examples are (Bombin,

1975) (Botero, 1979) (Flinta, 1983) (FAO,

1978, 1980):

- Exemption from all taxes

- Total or partial exemption from land tax

- Total or partial exemption from income tax

- Total or partial exemption from gift and inheritance tax

- Total or partial exemption from capital taxes

- Total or partial exemption from sales taxes

Tax exemptions aim to produce an immediate boost in the peasant's net income in the hope that the cumulative effect will be enough to benefit everybody. These and other measures can help a community progress beyond the subsistence level towards a more productive economy whose taxes can contribute to the country's welfare (Flinta, 1983). There is usually a maximum time limit and an upper and lower limit and land area which can be exempted, depending on the type of action it is wished to promote (Bombin, 1975).

The following examples illustrate how these exemptions have been applied:

- In Belgium, reforested land benefits from a twenty-year land tax exemption. (FAO/SF)

- In Denmark, plantations are exempt from tax for 60 years (FAO, S/F)

- In France, forested and reforested areas have a thirty-year land tax exemption. (FAO/SF)

- In Argentina, profits invested in new plantations and in silvicultural improvement benefit from various types of exemption (Republic of Argentina, 1972, 1974, 1974)

- In Colombia, special development areas are exempted from income and capital taxes, and are only taxed on 20 percent of the sale proceeds on the assumption that costs account for the remaining 84%.

Tax exemptions have various effects:

- Cost reductions (proportionate to exemption)

- Income and capital tax exemptions usually have most impact

- Sales tax exemptions help increase gross income and trim selling prices, encouraging market expansion

As regards the relationship between tax exemptions and the variables affecting incentive impact:

- Exemptions are only applicable at the early stage of development (1) where landowners in the project area pay tax on a significant portion of income; otherwise, the exemptions would be ineffective.

- The objective of the incentive (0) is to encourage landowners to invest in conservation and reforestation by making the operation more attractive financially. In other words, the constraint (Cn) imposed by lack of interest in the investment is removed by making it more profitable. Usually, only medium and large landowners are affected, since small-holders are frequently not subject to tax.

- Community motivation (M) is of a general rather than a local nature since exemptions usually have wide regional or national application. The benefits of these exemptions should be pointed out to owners - all too often, no attempt is made to publicize them and explain the advantages of such incentives.

- The duration of the incentive (T) should be long enough for landowners to complete all farm conservation (and any reforestation) works and profit from longer term investments (fruit trees, forests, etc.)

- The incentive is distributed (D) amongst tax payers agreeing to undertake plantation and conservation activities on their farms in return for tax savings.

- The incentive is recovered (R) by society if falling yields from taxation are compensated for by increased economic benefits arising from the measure.

This incentive is much broader. Any sum that a citizen invests in forest conservation, reforestation, or management is tax deductible within certain limits over a fixed period. This incentive is widely-used as it is applicable to any natural or legal person, whether or not they are land or forest owners, thus allowing large sums of capital to be channeled towards the target sector.

There are two basic situations:

- Where reforestation and/or conservation costs are offset against up to 100% of the income tax due. This requires knowledge of the relevant standard costs according to type of work, region, species, etc. (Bombin, 1975) (FAO, 1980).

- Where the value of new company investment - consisting in the issue or purchase of shares in forest enterprises - is offset against up to 100% of the income tax due (INDERENA, 1981).

Many countries have employed this measure in extensive reforestation programmes. In Brazil, it has been possible since 1966 to deduct the value of all afforestation and reforestation investments in State-approved projects from gross income (physical persons) and from taxable income (legal persons), up to a maximum of 50 percent of the tax due. A number of modifications were made to this incentive between 1966 and 1977, during which period 2.9 million hectares were reforested (Larrobla, 1983)(Moosmayer, 1977). In Jamaica, the cost of conservation works is tax deductible (FAO/SIDA, 1980), whilst in Colombia investment in forestry is tax deductible up to a maximum of one-fifth of the income tax owed (INDERENA, 1981).

The impact of the incentive in terms of the variables affecting it is described below:

- The stage of development reached by society, rather than by the community (I), is what is relevant here since these incentives have national or regional application and are aimed not at communities but at individuals and commercial and financial enterprises. It is not a measure appropriate to poor peasants or communities.

- The object of the incentive (O) is to channel tax revenues towards forestry investment (including reforestation and natural forest management). Whilst such measures may have a considerable impact, involving as they do a massive injection of resources into the forest sector, they cannot properly be classed as a community or peasant incentive.

- No particular motivation (M) is required on the part of forest or other enterprises, since the incentive is virtually a donation of capital. All that needs doing is to draw attention to the sector's potential profitability.

- The incentive can lift constraints (Cn) such as economic inability to undertake medium to long term operations, and investors' lack of interest in making such operations more profitable.

- As a rule, tax deductions have a maximum duration (T) based on how long the incentive's designers reckon it will take for its effects to be felt on sufficient scale to meet demand for certain products or to rehabilitate degraded forest land.

- The incentive is distributed (D) between tax payers, mainly medium and large ones. Smaller tax payers will be involved only if firms emerge willing to channel capital generated by tax deductions towards them. One positive approach would be to focus investment on certain areas or regions in particular.

- Although deductions reduce tax revenues, society still collects if the economic benefits of the resulting investments outweigh the fall in revenue.

Many peasants and communities are unable to obtain loans from the financial system (State or private), since they lack security for the loan or do not have anyone to act as guarantor.

There are various ways of solving this problem but the initial requirement is for owners to be grouped together in legally recognized community bodies. Once this is done, the following solutions are available:

- For short-term loans: forward sales contracts for group produce, the crop itself providing the security (Gregersen, 1978).

- Medium and long-term loans: the community itself can guarantee or provide security for the loans. Revolving funds are particularly useful here.

- Medium and long-term loans: the State acts as guarantor of the loan, together with a forward sales contract (Gregersen, 1978).

Forward sales contracts are negotiated on the basis of an average price; this ensures the operation is worthwhile by guaranteeing a minimum income, protects small and medium producers from market fluctuations, and provides them with security for their undertakings.

Another interesting aspect besides security is-insurance against natural risks (Flinta, 1983).

For example, forest plantations can be insured against fire - the amount of the premium depending on the age of the forest, its area, and the cause of the fire. Such insurance can work as an incentive since it eliminates risks and may provide sufficient security for a loan (Chile Forestal, 1984). Where small owners are involved, the insurance can be negotiated by the community with each owner contributing in proportion to the value of his land, forest patrols being a collective responsibility.

As regards the variables affecting these incentives:

- For the purposes of security and insurance, the community needs to have reached a stage of development (I) capable of supporting organizations which can back up and strengthen the bargaining power of the group.

- The objective (O) of security, guarantees and insurance is twofold: give low-income peasant groups access to credit and legally empower them to negotiate.