Chapter 1 underscored the objectives of this Guide,listing as well what it does not set out to do. It does not tackle the creation of mountain watershed soil conservation plans and projects. The approach is the incorporation of incentives-into such plans and projects. The assumption is that sectorial and regional planning offices have the necessary staff and experience to formulate the various kinds of projects: this chapter concentrates on the strategic, tactical aspects of incorporating incentives.

The widespread belief that watershed conservation projects are barely feasible economically and have a low rate of return financially is fundamentally wrong (Table 3.3 and item 3.2.5.). The real problem is the intrinsically long investment period and the series of restrictions laid on the interested parties, including governments. Additional problems are lack of information on the economic and financial benefits, poor economic status of governments and farmers, inexperience and therefore lack of technical expertise in this area by government and farmers, lack of State interest (and owner interest) because long term action has a low political yield. The State is legally weak - its apparatus and institutions need to be made more flexible. The legal standing of farmers with respect to land tenure and guarantees needs to be clarified. Peasant access to markets (which are in the grip of middle-men) is poor, and local and national authorities do not exercise any real power over marketing.

It is also increasingly clear that world population trends and the status of natural resources now preclude temporary conservation and rehabilitation measures. The Government needs to take definite action, accepting the corresponding staffing and budget costs. A Government landowner or farmer with a sufficiently long-range perspective can easily perceive that proper resource use and conservation is comparatively cheaper than soil rehabilitation. (FAO/WFP, 1984).

It is also clear that existing restrictions and the need to conserve and rehabilitate soils demand a straightforward, well-implemented policy on natural resources with incentives as a fundamental component. As closely as possible, this must be part of integrated agricultural development in the broad sense, considering the full range of production needs, land carrying capacity for continuous production, establishment of the necessary structures to ensure project continuity, guaranteed, consistent aid (incentives), and the willingness of the rural population to change its way of doing things and to undergo temporary restrictions for future gain (FAO/WFP, 1984). The need for a clearly-defined policy is echoed in the requirements of the World Bank and other major financing agencies, which want projects submitted for their consideration to have a favorable, lasting impact on the environment (Bochet, 1983).

Two immediate levels of action can be distinguished within a given country: the regional or national plan, and the specific project. The procedure is quite different in each case. Figure 2.1 of Chapter 2 shows that the design of a plan is strategic - a way of declaring war on erosion and facilitating the rehabilitation and conservation of natural resources. A "Management Plan" for a specific watershed is, on the other hand, a tactical approach, a battle rather than a war, which attacks one specific aspect of the whole problem.

The next section analyses natural resources strategies and incentive planning for specific projects or whole countries.

The point of the strategy is to achieve policy objectives. This will depend on a number of factors, including:

- Prevailing system of Government

- Whether the Government has a clear policy on natural resources problems

- Previous experience of natural resource policies

- Status of natural resources and how important they are to the population

- The financial status of the Government and of the rural population

- The technical and administrative capabilities of the Government.

The range of possibilities is great: but a number of examples do emerge from (conscious or unconscious) strategies.

Many countries have attempted to conserve natural resources through very strict, rigid bodies of legislation, in extreme cases virtually preventing exploitation of forest resources and banning agriculture. This kind of strategy overlooks the problems of the communities living in the soil/water/ forest environment. They fail to enlist people's active participation in conservation and rehabilitation programmes (FAO, 1980).

This approach also ignores the fact that natural resources require rational use to benefit the population and avert land degradation.

Such a strategy can be successful, assuming a well-equipped, well budgeted forest service, geared for conservation and rehabilitation work where necessary (also assuming there is no man/land pressure on resources).

Countries without a strong administrative forestry body and short on resources often have recourse to legislation, but the result can be illegal occupation of lands and destruction of land and forests with consequences which cannot always be measured or foreseen.

Project continuity cannot be guaranteed when the State intervenes without the participation of the target community using salaried workers.

At some point in time, almost all countries adopt such an approach but it can only be justified as a transitory means of halting a very rapid pace of degradation.

This kind of strategy consists in setting up an incentive package, particularly fiscal incentives and subsidies targeted at reforestation for industrial purposes. The State is usually a passive body, merely ensuring compliance with rules and regulations on subsidies, tax exemptions and tax deductions.

The indirect approach has been successfully applied in countries such as Spain, Brazil and Chile. State participation may or may not include technical assistance, the sale of plants or other kinds of aid.

The strategy is indirect; the goal is to make the operation profitable. People participate only as hired laborers on a reforestation project (Moosmayer, 1977) (Bombin, 1975) (de Abreu, 1978) (Republic of Chile, 1980). In the aforementioned countries, subsidies, tax exemptions and deductions have been extraordinarily successful but *the clientele is the medium or large landowners and the medium or large industrialist. Naturally, this approach largely solves the problem of reforesting degraded and marginal lands, but does make the peasant an active, involved participant and therefore offers no solution to the problem of integrated rural development.

In some instances, when the target is well within reach, such schemes become more flexible and begin to incorporate rural development projects within the scope of the system. In Chile, for example, the subsidies system returns 75% of the costs of reforestation to landowners, in accordance with standard costs per region. Last year, work was begun with three small rural communities. One is a highlands community which will be reforested with fodder shrubs to support llama livestock development, the other is a group of small landowners who will work with a reforestation project to produce wood, and the third is reforestation for silvo-pastoral purposes. (Chile Forestal, 1981).

This system produces spectacular results because it makes forestry profitable for possessors of capital and, once the prime goal of producing a major raw material base for industry has been achieved the project can be retargeted at community development. It is advisable not to modify the regulation and administration of such a scheme but simply try to backstop it.

This is applicable to countries beginning soil conservation and rehabilitation efforts with one or two specific projects. These projects usually involve three groups: the national agency, international organizations and the community.

The specific project or projects is usually selected in response to an urgent problem such as drought, hurricane or flood damage. Such projects test a full range of methodologies, and afford experience in implementation of works, application of incentives, community participation and training and technical assistance. Successful projects may become showcases, convincing peasants that conservation is both necessary and beneficial and Governments that the project needs to be continued.

This was the case of Honduras, which developed a modular system applicable countrywide; and Ethiopia, which began with a 5000 ha project, now national in scope which has achieved great progress and enlisted active peasant involvement (FAO, 1981) (FAO, 1983).

The twenty-four hour farm rehabilitation programme of the Soil Conservation Service of the United States Department of Agriculture in the Great Plains region enlisted farmer participation through demonstrations on various farms, another showcase project. A vast outlay of resources was deployed for twenty-four hours to build all works needed on a small farm. The target was maximum positive impact and immediate demonstrable benefits (USDA, 1957).

This is the kind of action taken in most developing countries where every year funds are earmarked for soil conservation and rehabilitation, though resources are scant and/or the conception of natural resources is fuzzy at best. Government agencies work concomitantly on a great number of watersheds but financial resources are few and intensity is low. There is no overall approach; soil conservation works are a patchwork affair and the few available funds are stretched too thin to be truly effective. One example is building terraces without providing technical assistance, frustrating the expectations of people who thought their situation would improve through more intensive farming. Reforestation without forest maintenance leads to destructive forest fires or insect pest attacks. This strategy ( if such it can be called) is very wrong. Peasants mistrust such systems and Government itself is reluctant to give higher priority to a sector which, as the years go by, has nothing to show for the investment.

Such action implies that a country has taken full cognizance of its most pressing natural resource problems. It probably has a man/land ratio problem as well. A vast effort of high intensity, nation-wide action is deployed, including massive involvement of the population at all stages of the plan. Rural development and rehabilitation is also a top State priority. A sort of national movement or crusade is formulated within an ideological context of people's participation and recovery of the country's resources.

Striking examples of this kind of action are China, which planted 29 million ha in thirty years and Korea which planted 851000 ha in a little under five years. There were a series of additional works in both countries.

Much of the work is done by unremunerated, voluntary labour. The people are aware of the individual, local and national benefits of these activities (FAO/SIDA, 1983)(FAO, 1982).

The situation in Korea is similar to that in Chile but in reverse fashion and on a different scale. Chile is making a timid start at a scheme designed to establish industrial plantations in support of rural development projects. In Korea the second tenyear plan, utilizing a comparable community participation scheme, will shift from an emphasis on fuelwood plantations and resource protection to a central focus on industrial plantations, the scale remaining the same as in the first plan.

It is too late now for developing countries to engage in productive legal. refinements. Most countries have laws which if enforced would end the destruction of natural areas,provide the necessary trained staff, and produce considerable funds to finance projects. But much of these laws remain a dead letter: good intentions but few results. The most appropriate global strategy in each case needs to be identified by the relevant government officials, particularly forestry staff, based on the specific situation of that country. There is some urgency, however, and overall strategy has priority.

There is also a problem of definition. Should one begin to attack the problem by a national-level sectorial analysis (as suggested by McGaughey and Torbecke, 1981) focusing on how the forestry sector interrelates with other sectors and its contribution to economic development ? Or should the first approach perhaps be a specific project ? It would seem sensible to do both, i.e., attack the problem of major conservation and rehabilitation from the sectorial angle and at the same time formulate and implement specific watershed management and reforestation projects.

The developing countries' natural resources and population problem was described in Chapter I --id can be summarized as follows:

- Developing countries have growing populations

- Land resources are either scarce (countries with high population densities), or poorly distributed and therefore not accessible to peasants (latifundio minifudio complex), or carrying capacity (arid and semi-arid lands) is low

- Natural resource degradation is a vicious circle in which scarce access to land is matched by low productivity under current farming practices, limiting rural people's expectations as to work, food, energy, water and the like

- The up shot is rural poverty, migration to urban areas and urban poverty.

It seems appropriate to ask which of the latter misfortunes is preferable, rural poverty or urban poverty ? This is a hard question to answer as both have their own set of social evils. It would seem important, however, to develop the potential of rural areas as much as possible, thus curbing the flight from the land.

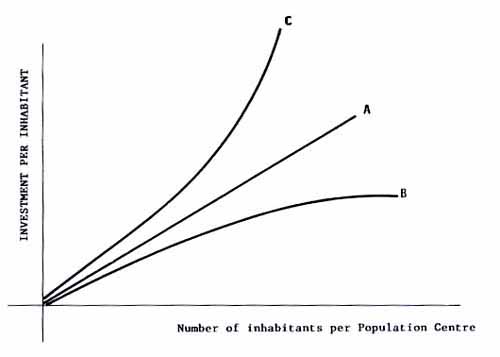

Figure 5.1 attempts to outline one of the underlying problems of emigration. When a peasant emigrates to the city there are a series of social costs which the society "should" incur to fit him in:

- housing

- employment

- urban transport

- health and education

- etc.

The costs of these services and minimum conditions are higher in the city than in the country. The bigger the urban centre the higher the cost per inhabitant. Figure 5.1A shows three possibilities: the investment per inhabitant grows at a constant rate (A), at an increasing rate (C), at a diminishing rate (B).

Figure 5.1B shows the probable trends in investment per inhabitant by urban size. The cost goes up as urban size increases, peaks, and then diminishes to a low which constitutes optimum population size. After this low, the line swerves upwards again with urban congestion, problems of the cost of land, water supply and the like. Figure 5.1B leads us to venture a conclusion: if the amount of money necessary to settle a rural dweller in the city were invested in rural development the savings alone from such an investment would produce sustained rural development. In other words, urban problems cannot be solved simply by urban development; more energetic intervention in rural areas is needed. (Adeyoju, 1978).

Statistics of this sort are changing the outlook of governments, who are now more interested in formulating coherent policies in the renewable natural resources sector. Other factors (McGaughey, Torbecke, 1981) are:

- the growing scarcity of forest products, particularly tropical forest products

- the fact that energy shortages have driven up the value of wood on local markets, often the only available source

- the fact that more people and more livestock have meant more deforestation

- the need to protect major watersheds in order to conserve valuable soil and water resources

- the growing demand for various forest products, particularly in the intermediate-income countries

- the growing awareness of the undesirable environmental impact of resource abuse, e.g. the Amazon Basin.

Based on the foregoing, governments are taking a new look at the forestry sector and renewable resources in general as a key element in long-term economic and social development.

The close link between natural resources and rural development is clear evidence that neither agricultural development nor forestry activities alone can solve rural problems. The answer probably lies in knitting together agriculture, forestries, fisheries and special conservation and land and water rehabilitation works as components of master plans (McGaughey, 1981).

Some major policy components comprising significant advances in the conservation and rehabilitation of mountain soils might be (McGaughey, 1981) (FAO/WFP, 1984) (Spears, 1978) (McGaughey, Torbecke, 1981) (Yachkashi, 1976) (Burley, 1982) (Michaelsen, 1983):

- The natural resources of a mountain watershed should be considered globally because the various components are so heavily interlinked, as mentioned above

- Institutional reform and improvement is a prerequisite to good design and implementation of integrated sectorial development plans and programmes

- Effective incentives need to be devised to accelerate integrated development if there is a gap between what the individual sees as an investment benefit and what the government considers to be in the national interest

- Conflicts between the various activities of agriculture, fisheries, forestry,

conservation and rehabilitation in integrated plans

and programmes need to be identified

- The many economic and financial benefits of integrated rural development need to be quantified and pointed out to policy makers

- The relationship between integrated rural development and social development objectives need to be identified

- The rural population needs to be involved in the design and follow-up of plans and projects, not simply their implementation

- Legislation consonant with the socio-economic patterns of the target group and the natural resource (timeframe, indirect benefits, uncertainties, external factors, etc.) needs to be formed

- Policies and legislation in other sectors need to be reviewed for possible application to soil conservation and rehabilitation and community involvement in such work.

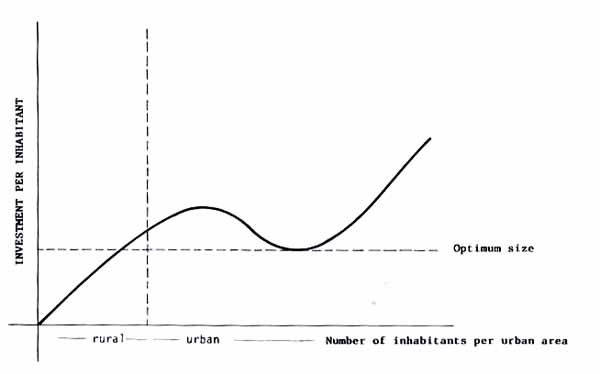

Any plan takes its inspiration from a national, sectorial and/or regional development policy. A plan supposes a fairly conventional series of steps in terms of design, as Figure 5.2 shows.

An integrated rural development plan for soil conservation and reforestation involves various components:

i) The sectorial policy (agriculture, forestry, environment) together with policy on related sectors (economic and social development, energy, fiscal and monetary sectors) and other sectorial plans impose certain preliminary objectives upon the plan.

ii) The inventory of soil, water, forest resources and population, together with the

analysis of the underlying causes, e.g.

resource degradation, migration, etc., provide the basis for a critical analysis -

particularly of variables which indicate sombre trends. This critical analysis leads to a

further definition of objectives.

iii) With the objectives identified and assuming that the inventory considers institutional aspects and resource availability, the plan proper is formulated, including resources (what ?) strategies (how ?) and targets (how much ?).

iv) The plan is pre-evaluated before implementation (ex-ante). The next step can either be final adoption or postinventory review (or any subsequent stage).

v) The plan is implemented and execution begins. Periodic checks and evaluations are

recommended during the planned

project time period (ex-inter). This may lead to new feedback and review and modifications

of some aspects in the light of project experience.

vi) In finalizing the plan a last overall (ex-post) evaluation is needed, which may lead to a review of sectorial policy. This review could also be the outcome of some intermediate stage of monitoring.

Certain situations specific to a plan of conservation and reforestation plans must be established:

- Inclusion of the sectorial analysis dimension in plans, thus enabling institutions to formulate policy and international cooperating agencies to formulate coherent investment strategies in the sector. The strategy will recommend project priorities within the plan and the respective timetable of investments (McGaughey, 1981).

- Need to give special consideration to land use planning (the allocation of land use per area), which will guide watershed management planning (action priorities within a country's watersheds). This assumes a system to determine action priorities (Hidalgo, 1981).

- The time factor must be very carefully considered in conservation and reforestation plans requiring fairly long planning horizons. From the very outset, however, such plans do represent a major benefit for the target populations in that they provide employment (Fernández, 1983).

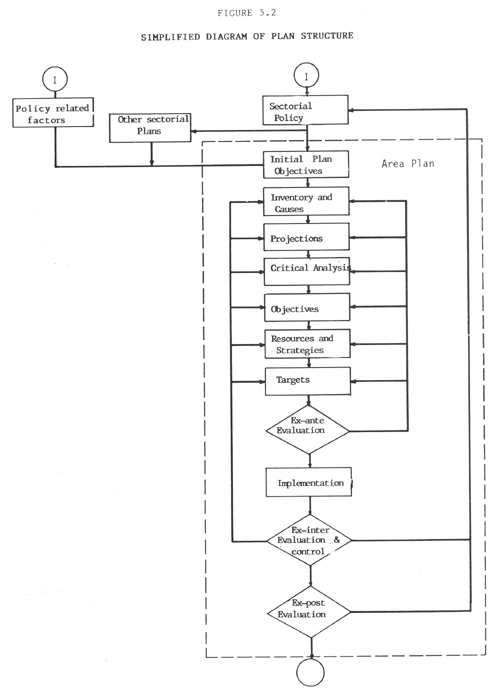

The scheme of a plan (Figure 5.2) and project are similar but a project is much more detailed and its geographical circumference much smaller.

Figure 5.3 shows a simplified diagram of the operations of a project. Prominent in this diagram is the need to evaluate, monitor and correct implementation (or other) gaps which may arise in the project.

The stages in a forestry project from start to finish (with greater or less variations) are the following:

- Origin of the idea and preliminary profile

- Project preparation

Preliminary objectives

Background, framework

Physical inventory

Socio-economic inventory

Projection of present situation

Critical analysis

Objectives defined

Alternative plans

Criteria for decision (Evaluation)

- Pre-implementation action

Constitution of the local body

Motivation

Community organization

Tailoring to make the system more operational

- Implementation

Planning

Monitoring

Evaluation (ex-inter and ex-post)

Continuing execution

There are slight differences in the existing literature on this kind of diagram but all components can be listed under one of the above categories (Speidel, 1971) (FAO/SIDA, 1983) (FAO, 1980).

The following aspects need to be considered in the formulation of watershed management projects. The stages of project formulation will not be emphasized.

A watershed management project should also consider social and economic development. (Flinta, 1983) (Hidalgo, 1981) (Botero, 1984).

A watershed management project must have two major components, i.e.: the conservation infrastructure works and the package targeted at boosting productivity, which includes technical assistance, training and evaluation (Flinta, 1983)

A good strategy is to consider the forestry components as secondary and complementary to shortterm activities such as agriculture and livestock production (Fernandez, 1983) (FAO, 1984)

A watershed management project needs to combine a number of land uses at the same time. Crops with cattle, crops with forests, cattle with forests, in tandem or in succession, not forgetting the impact on soils (Flinta, 1983) (FAO/WFP, 1984) (McGaughey, 1981).

The factors underlying people's motivation for participation in the project need to be pinpointed as these may limit people's participation. People's needs and aspirations need to be known and therefore the sociological component is very important (Atmosedaryo, 1978)

Depending on the extent of watershed degradation, it is important to emphasize prevention of environmental damage as a concomitant of production rather than putting the emphasis on soil rehabilitation. (FAO/SIDA, 1980) (FAO/WFP, 1984) (Government of Mexico, 1979)

Within the project context, a special effort must be made to evaluate how many working days are available with respect to the eventual work to se done, and the proper form of compensation (Flinta, 1983)

- Soil conservation and reforestation projects should involve a high level of vertical integration. This produces such advantages as increased value added which remains within the community, diminishing the risk of projects falling into the hands of unscrupulous middle-men with monopoly powers (Fernández, 1983). Vertical integration is closely linked to the use of available working days.

It is difficult to finely detail incentives for a national plan, as these must often be designed to fit site-specific situations. Nonetheless, certain aspects of the incentives question need to be underscored as part of land use planning policies and plans for conservation and reforestation of upland areas:

- Incentives need to be classified as general in nature or as targeted at specific priority regions of the country

- Incentives which are nation-wide or region-wide in scope must be established and regulated by a legal body. This is to guarantee users that they are entitled to insist on State compliance where they themselves have complied with the established regulations (Larrobla, 1983)

- National and regional incentives also need to be based on the yields produced by those receiving the incentives. In this instance, the redistribution of income is not necessarily an objective, but neither is the incentive necessarily linked to productivity (Gregersen, 1978)

- Land tenure and its regularization are an integral part of any national incentives scheme, else the incentive users are in no way guaranteed that they will reap their fruits of their labours (Flinta, 1983) (Costabal, Romero, 1979)

- Within a plan, incentives must be designed to ensure continuity of plan activities even after the incentive is no longer applied (Flinta, 1983)

- Incentives must be well planned and realistic, i.e., there must be funds to back them and they must complement one another and be carefully promoted beforehand to be effectively used (du Saussay, 1983) (FAO/SIDA, 1980).

Table 5.1 shows the use of incentives in conjunction with certain limiting factors within the community. Section 4.1 recognizes the following as limiting factors: a target population is unaware of the benefits of the project; technical and economic skills are lacking; there is little interest in the activity; legal skills are unavailable, as is fair access to markets. Additional constraints are the man/land ratio, social and productive community organizations, awareness of environmental issues, community organization and the availability of land. The table sets out guidelines on incentives for specific situations.

Generally speaking, incentives most often used at the national level are: subsidies, credits, tax exemptions and deductions, endorsements, guarantees and insurance, input and commodity prices, secure land tenure and technical assistance.

| INCENTIVES | GAPS | ||||

|

Awareness of project benefits

|

Technical skills |

Economic Capacity Infrastructure

|

Capital | Legal Capacity | |

| DIRECT INCENTIVES IN CASH | |||||

| Grants | X | X | |||

| Payment of daily wages | X | X | |||

| Subsidies | X | X | |||

| Credit | X | X | |||

| Revolving Funds | X | X | |||

| Agreements on cost/ benefit sharing | X | X | |||

| DIRECT INCENTIVES IN KIND | |||||

| Food aid | X | X | X | ||

| Agricultural inputs | X | X | |||

| Tools and implements | X | X | |||

| Inputs for community construction | |||||

| Inputs for road building | |||||

| Inputs for irrigation systems | X | X | |||

| Feed for cattle and other animals | X | X | |||

| Work and production animals | X | X | |||

| Allocation of State-owned forests | X | ||||

| INDIRECT FISCAL INCENTIVES | |||||

| Tax exemptions | X | ||||

| Tax deductions | X | ||||

| Collateral, guarantees and harvest insurance rates | X | ||||

| Rates, prices of inputs and commodities | X | ||||

| Security of land tenure | X | ||||

| INDIRECT SERVICE INCENTIVES | |||||

| Technical assistance | X | X | |||

| Marketing, storage, roadworks | |||||

| Education and training | X | X | |||

| Machinery and equipment | X | ||||

| INDIRECT SOCIAL INCENTIVES | |||||

| Services | |||||

| Community constructions | |||||

| Community organization | X |

| INCENTIVES | GAPS | |||

| Fair access to market | Adequate land/man ratio | Community social facilities | Community producer ass oci at ions | |

| DIRECT INCENTIVES IN CASH | ||||

| Grants | ||||

| Payment of daily wages | X | X | ||

| Subsidies | ||||

| Credit | ||||

| Revolving Funds | X | X | ||

| Agreements on cost/benefit sharing | X | |||

| DIRECT INCENTIVES IN KIND | ||||

| Food aid | X | X | ||

| Agricultural inputs | X | |||

| Tools and implements | X | X | X | |

| Inputs for community construction | X | X | ||

| Inputs for road building | X | X | ||

| Inputs for irrigation systems | X | X | ||

| Feed for cattle and other animals | X | |||

| Work and production animals | X | |||

| Allocation of State-owned forests | X | |||

| INDIRECT FISCAL INCENTIVES | ||||

| Tax exemptions | ||||

| Tax deductions | ||||

| Collateral, guarantees and harvest insurance rates | ||||

| Pates, prices of inputs and commodities | X | |||

| Security of land tenure | ||||

| INDIRECT SERVICE INCENTIVES | ||||

| Technical assistance | X | |||

| Marketing, storage, roadworks | X | X | ||

| Education and training | ||||

| Machinery and equipment | X | X | ||

| INDIRECT SOCIAL INCENTIVES | ||||

| Services | X | X | ||

| Community constructions | X | X | X | |

| Community organization |

| INCENTIVES | GAPS | |||

| Interest due to low returns |

Knowledge about environmental problems

|

Community Organization | Land | |

| DIRECT INCENTIVES IN CASH | ||||

| Grants | X | |||

| Payment of daily wages | X | |||

| Subsidies | X | |||

| Credit | X | |||

| Revolving Funds | ||||

| Agreements on cost/benefit sharing | X | |||

| DIRECT INCENTIVES IN KIND | ||||

| Food aid | X | X | ||

| Agricultural inputs | X | |||

| Tools and implements | ||||

| Inputs for community construction | ||||

| Inputs for road building | ||||

| Inputs for irrigation systems | X | |||

| Feed for cattle and other animals | X | |||

| Work and production animals | X | |||

| Allocation of State-owned forests | X | |||

| INDIRECT FISCAL INCENTIVES | ||||

| Tax exemptions | X | |||

| Tax deductions | X | |||

| Collateral, guarantees and harvest insurance rates | ||||

| Rates, prices of inputs and commodities | X | |||

| Security of land tenure | X | |||

| INDIRECT SERVICE INCENTIVES | ||||

| Technical assistance | X | X | ||

| Marketing, storage, roadworks | ||||

| Education and training | X | X | ||

| Machinery and equipment | X | |||

| INDIRECT SOCIAL INCENTIVES | ||||

| Services | ||||

| Community constructions | ||||

| Community organization | X | X |

In drawing up a conservation and reforestation plan or project, special care has to be taken with the institutional capabilities of the executing agency. If the executing agency is too small with respect to the plan, targets will not be met and false expectations will be aroused among the target communities. If the agency is oversized, the plan can be very costly and the incentives will produce more social benefits.

For an incentive system to work properly with respect to the agency in charge, the following are necessary:

- The agency must have real coverage of the target areas, and enough staff to both promote the plan and provide the technical assistance, education and training required to carry it out. (McGaughey, 1981) (FAO/WFP, 1984)

- The needed inter-agency, bilateral or international cooperation plan should not exceed the capabilities of the executing agency staff (Burley, 1982)

- There must be a good balance within the agency between headquarters managerial staff and the field staff who are actually bringing the new techniques to the farmer, supervising the work and establishing contact with the community (FAO/WFP, 1984)

- Local administrative and decision-making procedures of the agency implementing the plan need to be decentralized enough to be effective

- The institution must have solid technical and research data to backstop field agents

- Where possible a watershed authority should handle the budgets and staff of the institutions participating in the project (or else a director should be responsible for coordinating the budget and staff of participating agencies) (McArdle, 1960) (FAO, 1980)

- The role of the executing agency varies in accordance with project objectives. Sometimes the objective is to attract capital and capabilities not presently attached to the project. Sometimes the agency's interest is to work directly in the field, acquiring field experience (Flinta, 1983).

- The institution must stress that quality targets as well as quantity targets need to be met. (FAO/SIDA, 1980)

- The institution can lower TA costs through demonstration sites illustrating direct conservation works as well as production (FAO/SIDA, 1980)

- The institution needs to devise simple, non-bureaucratic procedures with no red tape so that incentives can become real tools of rural development (FAO/SIDA, 1984)

- The field staff of a rural development project needs to be trained in the planned conservation works and crops and must be accessible to peasants as well. (Flinta, 1983) (Government of Mexico, 1979)

- If the peasant or community has done its part, the institution must be on time with its grants (Hidalgo, 1978)

- Staff turnovers during the project period are not advisable and, wherever possible, field staff should be from the local community (Hidalgo, 1978).

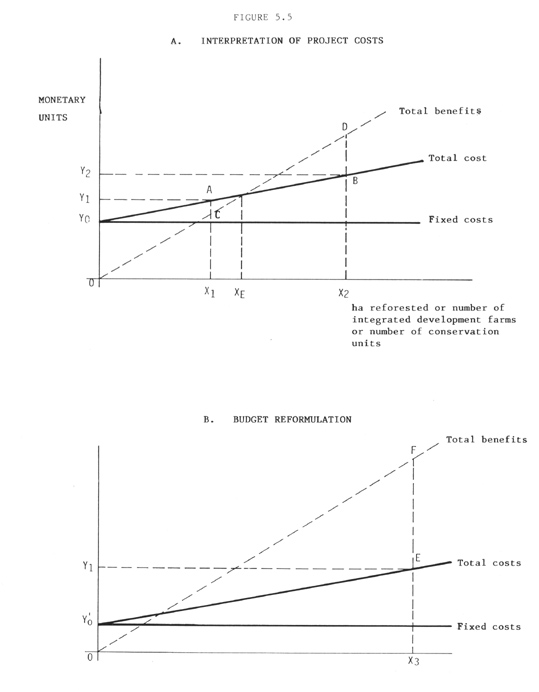

The economic benefits of a project are fundamentally dependent on capabilities of the local implementing agency, as are, by extension, the benefits for society. A project can be a financial success for participating peasants and communities and a failure in social terms. Figure 5.4A describes flow of costs within a standard project.

If the institution has a budget OY1 it can execute a total of OX1i physical units of project goals. In this instance, project benefits are only X1C, whereas costs top X1A. There is a net equivalent loss of CA. if all costs and benefits are expressed in economic terms the CA figure is society's loss. If, on the other hand, the institution has a budget OY2 it can execute a total of OX2 physical units of project targets. In this instance the project benefits top X2D and the costs X2B. There is a net benefit for society of BD. What we are trying to show is the following:

- The institution may have a problem of too much installed capacity and too little working budget which prevents it from attaining the lower limit above which the society clearly benefits from the project (XE).

- In this situation there are two possible choices:

i) The institution gets a higher budget for operating costs (Y0Y2 which will give it a physical target of OX2 units and produce a benefit for society of BD.

ii) The institution's budget is not raised and therefore it has to cut the project down

to size (Figure 5.4B). At the project

level the institution reduces fixed costs and uses the savings for operating expenses. The

new budget is OY1 , as before, but

divided into OX'0 in fixed costs and Y'0Y1 for operating

expenses.Under these circumstances the results will be OX3 physical units of

target with X3E in total costs and X3F in total income, for a social

benefit o EF.

The graphs clearly show that the cost structure of the institution as well as productivity need to be known quantities in order to decide whether the project is of real benefit to society.

To produce acceptable results and become truly operative an incentive project needs proper funds. Each incentive costs a certain amount of money. This must be allotted through regular or extraordinary budgets (cash funds) or administered (government funding). Some incentives involve temporary loss of income, e.g., reduced fees, rents, interests, taxes, etc. (Flinta, 1983).

A national plan to fund incentives must take the following into account:

- There are incentives which must come out of State budgets such as: subsidies, national bank loans, initial contribution to revolving funds, the State portion of shared costs, and the supply of various kinds of inputs (Flinta, 1983)

- Some incentives must be State-funded but if the target has efficient use of existing infrastructures the amounts of money involved are fairly small: technical systems, education and training, machinery and equipment (as services) and community organization. Often enough existing facilities and redistributed staff and resources are sufficient. Regularisation of land tenure, where surveys are involved may fit this pattern.

- Some incentives involve nothing more than an administrative decision or regulation. The cost of the action is solely the monitoring needed to ensure compliance with its terms. In such cases the loss of tax recovery in State budgets must be taken into account. Secure land tenure comes under this heading when action consists solely of enactment of a law.

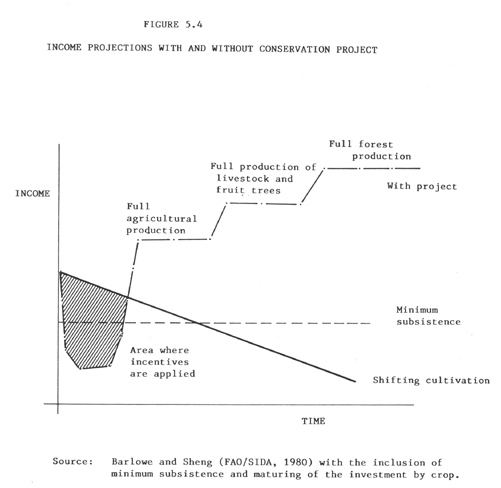

Source: Barlowe and Sheng (FAO/SIDA, 1980) with the inclusion of minimum subsistence and maturing of the investment by crop.

Some incentives involve bilateral agreements or cooperation with international agencies, such as food or inputs for work (von Maydell, 1976).

Some incentives require monetary policy action prior to implementation, such as credit issued by a private bank. But the percentage of the portfolio to be allocated to the sector, terms, interests and the like are determined by the government (Flinta, 1983).

Incentives and the funds to grant them must be provided on a regular, annual basis and cover the needs of the plan. (FAO/WFP, 1984).

Sources of financing for incentives are:

The regular national budget with an annual allocation sized in accordance with the objectives and length of the plan (Flinta, 1983).

Special budgets for the initial contribution to national funds or regional revolving funds.

Special taxes, such as taxes on timber extraction, wood trading, import and export, concession rights or other activities connected with the sector. This income is then invested within the sector. This can be made more flexible by allowing tax payers to invest the amount in the kind of works which the tax is intended to promote. Special taxes can be used the ' o set up development funds or national financing funds, e.g., for credit. Speculative activities can also be taxed and the funds channelled to the sector. (Flinta, 1983).

Obligatory investment of a percentage of the total costs in largescale works which are dependent for their existence on environmental protection. Power plants are one example, as are dams for irrigation and drinking water, and so forth. Sometimes an additional 10 percent allocated to reforestation and conservation works can lower the annual operating costs by increasing the useful life of the works and cutting operating costs. (Bochet, 1983).

Recovery of loans and other recoverable services, which can be reinvested in conservation and reforestation.

Reforestation and conservation plans can be included in broader programmes so as to attract funds from other sectors. Any of the above channels would be appropriate.

Funds can be provided by credit from such international agencies such as the World Bank or the Regional Banks of Africa, Asia, Latin America or they may come from food and other contributions as a result of agreements with countries and with international agencies.

Community enterprises can be set up to generate sufficient income to finance certain kinds of works. The study for a project in Venezuela called for a sandpit which would generate income to finance a large part of the community work and general conservation (sediment storage dams, settling basins, gulley filling, etc.). (CONARE/USB, 1981).

In any case, any use of State funding should include three fundamental aids within the incentives package:

i) Secure land tenure to ensure farmer readiness to cooperate with long term action;

ii)loan endorsements and guarantees;

iii) backstopping the community organization as a co-debtor and channel for credits and contributions for the community as a whole.

It can now be considered an established fact that plans attempted without community participation fail (FAO/WFP, 1984). Massive mobilization of rural people and all vital forces of the community based on awareness-building of a political, religious or any other nature is an effective way of enlisting community participation. China and Korea are two very clear examples of this (Botero, 1983) (FAO, 1982) (FAO, 1983).

Conservation should be planned with the people and for the people. If the peasant is nothing but a salaried worker his sole interest is his day's pay. His genuine participation must be enlisted by asking for his opinions, objections and suggestions.

Table 5.2 suggests the need for participation by unorganized peasants who should then work together with the national, regional and local implementing agency at every stage of the project. It shows that participation shifts increasingly from national to regional and local bodies and from official agencies to the organized community.

Peasant participation has concrete targets for which there can also be incentives (Flinta, 1983):

- Keeping the community and the peasant within the watershed, consolidating land tenure, improving housing, getting more access to social services.

- Tangible, swift and obvious benefits for peasant work: improved land use and greater productivity, continuous paid work, improved compensation for day work, and a splitting up of the work load to include productive tasks done by the community, such as light industries.

- Economic consolidation through the formation of savings to be reinvested in the community, producing profits for the community as a capital partner with access to producer credit.

- Active participation in project formulation, execution, reorientation and administration.

There is no question that peasant participation can be enlisted with the incentives described in this Guide, but incentives alone are not enough. Hoskins (1984) has established a number of prerequisites to community involvement in conservation activities:

- Motivation: potential participants must be convinced that a problem identified by an institution is a priority for the community. If peasants are shown that the proposed project can help overcome present constraints, the results will be good. This is done by making the community part of the project planning process.

- Information: the population needs to be informed, the competent agencies need to clear up any doubts and encourage the rural poor to look for the right responses. The outcome of the promotion campaign should be a better informed peasantry.

- Viable options: the action options offered peasants need to be accessible. Solid financial and logistical backing must be guaranteed and any restrictions to peasant participation eliminated.

| OFFICIAL AGENCIES | PEASANT | COMMUNITY | ||||||

| STAGE | Nat. | . Reg. | Local | Unorganized | Organized | |||

| Passive Active | Passive | Active | Passive | Active | Passive | Active | ||

| 1. Origin, Idea and | ||||||||

| Preliminary Profile | - | X | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2. Project preparation | ||||||||

| - Preliminary objectives | - | X | X | - | - | - | - | - |

| - Background Frame of | ||||||||

| Reference | - | X | - | X | - | - | - | - |

| - Physical Inventory | X | - | - | X | - | - | - | - |

| - Socio-economic | ||||||||

| Inventory | X | - | - | X | X | - | - | - |

| - Projection of | ||||||||

| Situation | - | X | - | X | X | - | - | - |

| - Critical Diagnosis | - | X | - | X | - | X | - | - |

| - Final Objectives | - | X | - | X | - | X | - | - |

| - Alternative Plans | ||||||||

| (includes incentives) | - | X | - | X | X | - | - | - |

| - Decision making | ||||||||

| criteria | - | X | - | X | - | X | - | - |

| - Final Project | - | X | - | X | - | X | - | - |

| 3.Pre-Implementation | ||||||||

| Measures | ||||||||

| - Constitution of a | ||||||||

| Local Entity | - | X | - | X | - | - | - | - |

| - Motivation | X | - | - | X | - | X | - | - |

| - Community Organization | X | - | - | X | - | - | X | - |

| - System Fine Tuning | X | - | X | - | - | - | X | |

| 4. Implementation | ||||||||

| - Planning | - | - | - | X | - | - | - | X |

| - Monitoring | - | - | - | X | - | - | - | X |

| - Evaluation | X | - | X | - | - | - | X | |

| - Review and Re- | - | - | - | X | - | - | - | X |

| formulation | ||||||||

| - Ongoing Execution | - | - | - | X | - | - | - | X |

- Skills: The peasant needs to have or get the skills recommended by the development options, which implies technical assistance and training as well as education in the broad sense.

- Benefits: Both peasant and community must clearly perceive the benefits they will derive from the planned action, either direct profits from the action or else the incentives themselves.

In the specific case of a watershed management and soils conservation project, all of the recommended steps for evaluation must be followed (Gregersen, Contreras, 1979):

- Identification of Inputs and Products

- Quantification of Inputs and Products

- Appraisal of Inputs and Products and

- Comparison of Costs and Benefits

As can be seen in Figure 5.2, a soils conservation and reforestation plan requires three kinds of evaluation and therefore three kinds of incentive analysis.

- Ex-ante evaluation:

Once the plan has been fully formulated and before it has been implemented, the financial and economic costs and benefits of the incentives must be compared. This will show whether sufficient motivation is provided for community participation (when financial profitability is high) and whether the State (Society) would be advised to apply the incentive (when the incentive is economically profitable). A distinction is made between the profitability of the plan and of the incentive (where it is possible to separate the effects) to pinpoint whether the economic profitability is really produced by the incentive or whether the profit derives from some other aspect of the plan.

Sometimes the environmental impact of the plan is also determined (Burley, 1982).

In the case of a specific project, the economic analysis is of fundamental importance to an institution, as it will determine the project's profitability for the society. For the peasant, on the other hand, the financial profitability of the action on his own farm is the basic issue.

Moreover, to demonstrate whether the project represents a real benefit with respect to the original situation, a cost/benefit comparison needs to be made with and without the project. Otherwise, the project may well turn out to be profitable financially but the original situation (without the project) might be even more profitable.

An attempt must also be made to separate the effects of the incentives as such. To do so, the so-called sensitivity analysis is used. Certain conditions of the project are modified and the costs and benefits compared under the new circumstances. The following comparisons can be made for incentives:

- With and without credit

- With credit at different rate of interest and grace periods

- With and without subsidies

- With and without tax exemptions or deductions

- etc.

- Ex-inter evaluation:

This is a follow-up and re-evaluation of the plan or project in the light of the project results. This evaluation produces a much finer grid of the coefficient used, as it works not with estimates but with real figures. These intermediate evaluations are highly important and generally lead to restructurations of the plan, examinations of targets, reallocation of resources, new methodologies and the like.

In ex-inter evaluations, one may encounter situations where there is a lack of demand for increased output, a lack of effective standards and regulations for the application of the incentive, etc. (Flinta, 1983). The United States Forestry Incentives Programme is contemplating a periodic review of the results of the programme, taking into account cost effectiveness and analyses of efficiency by farm size, costs of subsidies per unit of area, levels of management, harvest volumes, financial returns and additional wood yields. (Risbrudt, Ellefson, 1983).

- Ex-post evaluation:

This is done at the end of the plan or project for the period as a whole. There is no question as to its usefulness for later stages or other plans. This is true in Korea, for example, where the evaluation of the first ten-year plan produced a shift of emphasis in which the second ten-year reforestation plan was oriented towards reforestation for industrial purposes using a similar method because the first had been so successful. (Bong Won Ahn, 1978).

There is a now classic graph explaining the needs of incentives in soil conservation and reforestation projects. This is the Barlowe and Sheng graph which is shown here in a modified version (Figure 5.5). In shifting cultivation, the evershrinking fallow period leads to continuous soil degradation and loss of productivity. This results in gradually diminishing income which can even fall below the subsistence level. In the implementation of a soil conservation project, the initial phase of building conservation infrastructure works involves an initial sharp drop in farmer income. This then shifts upwards past the subsistence level and eventually past the income produced by shifting cultivation. Later, as livestock and the medium-cycle crops such as fruit trees and fuelwood begin to produce, income levels rise another notch.

In the final stage, mature forests become even more profitable. During the stage in which the works are being built and until the short-cycle crops have begun to produce, the community must be helped through the application of incentives.

Annex 2 relates possible incentives to promote activities in the kind of projects covered in this Guide. Incentive use criteria should be situation specific. The incentives considered,universally fundamental because basic to almost any kind of action, were technical assistance, secure land tenure, education and training, and community organization.

At the level of the specific project, incentives all have the following fundamental objectives (FAO/WFP, 1984) (FAO, 1980) (Flinta, 1983) (Hidalgo, 1981) (Hoare, 1979):

- To keep the farmer on the land through improved, more diversified farming systems producing higher incomes;

- To generate self-development through community organization, stimulating the community's own capacity to help itself;

- To give recognition to the fact that the farmer has to work harder, benefits are delayed and income from his plot temporarily reduced

by the introduction of conservation practices and activities intended to benefit the community as a whole.

To reduce the amount of farm area through intensive production systems and by creating employment not linked to land use to lighten the pressure on the land.

To make the peasant a participant in the management of natural resources on a sustained yield basis and primary, long-term beneficiary.

To eliminate the causes of soil, forest and water degradation in the watershed area.

To educate the community via application of the incentive (nutrition, cultivation techniques, etc.)

Incentive effectiveness will often depend on another series of factors (Atmosoedaryo, 1978) (Botero, 1984) (FAO, 1980) (Michaelsen, 1983) (FAO/SIDA, 1980):

Project activities should ensure regular work and income throughout the year. Income should cover cash costs year round.

The incentive should serve as a catalyst for initiative. It should be considered fair compensation for work done, and not as a gift.

Incentives should produce lasting benefits, making the farmer autonomous and ensuring socioeconomic development continuity.

The full incentive package should not be delivered upon completion of soil conservation works; a portion should be retained for a prudent period of time during which the investment (terrace, plantation or whatever) is consolidated and maintained.

The incentive must tend to emphasize the implementation of mechanisms and methodologies over supplying money in cash. Where cash is supplied, the tendency should likewise be to invest more money in community development works.

The peasant must be paid more for works benefiting the local community and region, or other people's farms. The expectation must be that a farmer's work on his own farm will be largely voluntary.

The incentive package needs to be reviewed as and when new circumstances arise. Technology needs periodic review as well,

The incentive should not consist of a single action. It should be an integrated approach targeted at eliminating the battery constraints due to local physical and social circumstances.

Incentives which imply distribution of surpluses among contracting parties must be carefully and clearly regulated. No group should feel its interests are being neglected.

The incentive package needs to produce short-term and long-term results to ensure that the people will go on living in the watershed.

Incentives should be granted on a flexible basis. Demands with which the community is unable to comply should be eliminated beforehand.

For small upland mountain watershed soil conservation and reforestation projects, the most successful incentives have been:

- Food for work

- Production inputs and inputs for the community as a whole

- Social incentives

- Security of land tenure

- Technical assistance, education and training.

The following have also been used but at more developed stages of the project:

- Community revolving funds for short-term credit

- Medium and long-term loans

- Subsidies.

Fiscal incentives such as tax exemptions and deductions are not so frequent as initially the communities are quite poor and hence not subject to taxation.

Annex I analyses three (3) instances in which incentive systems were applied. Annex III takes a look at some of the problems in applying incentives to round out the text of this Guide.