Main issues in Chapter 6

Diversifying — other crops

Maize marketing conditions under the old state-controlled system

Why farmers should now consider diversifying

Calculating the cost of production of and returns from maize

Calculating the cost of production of

and returns from some other crops

(see also annex)

Many maize marketing issues are also relevant to other crops

Other crops that farmers could grow …

Farmers can no longer automatically assume they can make a profit from maize.

An early decision to diversify out of maize could be beneficial.

FORMER MAIZE MARKETING CONDITIONS

Under state-controlled maize marketing all farmers could sell their maize to the marketing board or cooperative at the same price. Marketing board depots were established more or less everywhere. While some farmers obviously had greater costs to get their maize to the nearest depot than did others, these costs were not very significant.

Farmers in some areas may have got better yields for maize than others but the marketing arrangements basically enabled all farmers to grow maize profitably, particularly in countries such as Malawi, Zambia and Zimbabwe where the price was usually set by the government at a high level and there was no competing private sector.

Under such a system farmers did not have to calculate whether maize growing was profitable. Unless they lived in an area which was really unsuitable for maize, they could assume that the government price would be enough to cover their production costs and give them a profit. This was the reason why several countries in the region went through a period of excessive surpluses, why governments went into debt to pay the farmers and why inflation rose to over 100 percent in some cases. It is also the reason why production of other crops often fell. Those crops were not subsidized by governments so farmers, naturally, switched from them to growing maize, even though their land may have been more suitable for other crops.

THE NEED FOR DIVERSIFICATION

The situation has now changed. Farmers can no longer automatically assume that, providing the harvest is good, they will make a profit from growing maize. Those who farm in areas where marketing costs for maize are high may well find that the return does not justify the costs. Extension officers therefore have a role to help farmers understand this situation, to help them calculate whether growing maize is still profitable and to help them identify alternative crops which may be more profitable than maize. These crops may include other food crops such as sorghum, rice, millet or roots and tubers, traditional cash crops such as tobacco, cotton or groundnuts, oil seeds such as soya bean, horticultural produce for the local market or export5 and, finally, newer crops such as flowers. In some locations livestock or poultry rearing may be an alternative to crop production.

While past pricing policies in some countries encouraged the production of just one crop, maize, this was always a risky approach. Depending on just maize for income was not a good tactic for farmers, particularly in areas subject to drought. Depending solely on maize is even more risky when maize marketing is liberalized. Advice which extension workers should now be giving farmers therefore includes:

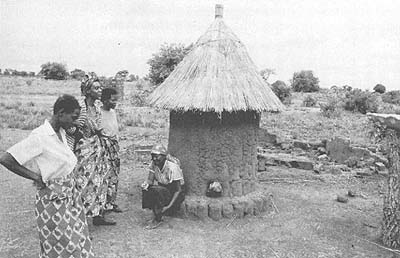

Farmers participating in an FAO Special Programme demonstration

Intercropping groundnut, cowpea and maize - Zambia

CALCULATING THE COST OF MAIZE PRODUCTION

The annex shows a crop budget for maize. In order to help the farmer with this calculation the extension worker needs to find out the following:

Where farmers provide their own labour then that labour cannot be considered a cost unless the farmer has alternative income-earning opportunities. If he has the chance of wage labour then he needs to calculate whether he will earn more from growing maize or from working for cash.

Even if the calculation shows that maize will be very profitable for the farmer, that does not mean that he should “put all his eggs in one basket” and just grow maize.

This approach has several problems:

Farmers therefore need to consider growing other crops as well as, or even instead of, maize. The crops they can grow will depend on their farming environment and on their marketing possibilities. With information about probable yields for various crops, their input requirements and likely selling prices, the extension worker should be able to advise farmers of the best crop mix for their particular area. The budgets in the Annex give some idea of the calculations required, but farm budgets more relevant to individual countries should be available from ministries of agriculture.

While diversification is highly recommended, the farmer does need to be sure that he can do the work. For example, it may not be a good idea to grow three crops which all need to be harvested at exactly the same time of the year, as the farmer may not be able to handle the workload. He also has to consider his cash flow — having to buy all inputs at the same time may also cause problems.

COST OF PRODUCTION OF OTHER CROPS

Crop budgets for groundnuts, sunflower, sorghum and cotton are presented in the Annex. Similar budgets produced locally, can be used by extension workers to calculate the profitability of other crops in relation to maize. The points already made regarding how to calculate the cost of production of maize also apply in the case of these other crops.

MARKETING AND PROCESSING OF CROPS OTHER THAN MAIZE

Many of the points made in connection with maize are just as valid for other crops. However, there are specific marketing and processing arrangements for each crop and some of those will now be discussed. As the move away from state marketing boards encourages producers to diversify into new crops and away from maize it becomes increasingly important that extension workers are in a position to advise them of the issues to be considered. The crops to be covered here are:

Paddy/rice

In a number of countries smallholders are growing paddy under irrigation. While a part of the crop is retained for domestic consumption, to be milled locally, farmers also usually sell part of the crop either as paddy or after milling, as rice. Prices for rice are determined by two main factors. The variety (there are preferred local types) and the quality (determined by the milling method, that is percentage of brokens and the degree of cleanliness and freedom from stones, etc).

Figure 11

Calculating processing costs

Assume that a rice milling operation converts paddy at the rate of 70 percent (0.7) and has saleable by-products equal to 25 percent of the paddy weight. Processing costs per kilogram of paddy have been calculated at $0.20 per kilogram on the basis of the mill's total annual costs divided by the number of kilograms of paddy processed. The buying price of the paddy was $1.50 per kilogram and the by-products have a value of $0.50 per kilogram.

Then the processing cost per kilogram of paddy is …

| One kilogram of paddy purchased | = | $1.50 |

| Processing costs or 1 kg × $0.20 | = | 0.20 |

| Total Costs | = | $1.70 |

| Less the by-product revenue of 1 kg × 0.25 × $0.50 | = | 0.12 |

| Break-even selling price per kilogram of paddy | = | $1.58 |

| Thus the break even selling price per kilogram of milled rice is … | ||

| $1.58 ÷ 0.7 | = | $2.25 |

Farmers must be aware that there is a need to harvest their paddy in a timely manner (avoid shattering and broken grains) and to dry their paddy correctly (on a drying floor or mat, to avoid dirt and foreign matter) to facilitate milling.

If the paddy is to be sold as rice after the farmer has had it milled in a local mill, then the price received for the rice will be determined by the factors mentioned. If the paddy has been husked but not polished, has a high percentage of broken grains and is “dirty” and perhaps of a variety which is not locally preferred (even if it is a high-yielding variety) then the prices received will be lower than other rice sold on the market. Farmers can add value to their paddy crop by storing it as paddy and subsequently selling it in a milled form if there is a good local demand for rice and if there are good milling facilities locally. However, if there are no local milling facilities or only husking machines are available, the farmer may be better off selling his crop as paddy to a local trader.

When paddy is turned into rice, the conversion rate is some 65–70 percent as the husk and the bran are removed. Farmers should, therefore, not directly compare local rice prices with the price they are receiving for their paddy as there is a loss of some one-third in the weight when paddy is turned into rice. Figure 11 shows a calculation of paddy processing costs6.

As with other crops, the extension officer can assist farmers by helping them to work as groups to facilitate marketing, by organizing transport and by providing links with local traders and millers. Considerable care should be taken not to promote diversification into paddy production unless there are mills and/or traders active in the area.

Sorghum and millets

These are more traditional crops than rice, commonly produced in the drier areas and mainly for local consumption. They can be useful crops to plant when lower-than-average rainfall is forecast. Attempts to commercialize sorghum and millet production have, however, often proved problematic. While research stations have come up with high-yielding varieties of sorghum, especially red varieties which are less attractive to birds, these tend to be bitter and are not acceptable to consumers. Moreover, marketing of sorghum has been beset by problems. In addition, attention needs to be paid to the variety that is grown, to ensure that it meets local tastes.

Commercial milling of sorghum and millet is not widespread, as the finished meal or flour is often more expensive than local maize. Milling is difficult and costly. These crops should be promoted mainly for subsistence and for local sale as grain unless there are identifiable marketing or milling outlets available.

Drying millet on a rack — Uganda

In some countries, there is a demand for finger millet and some sorghum types for local brewing. This can be a remunerative but limited market. However, before these crops are promoted due attention must be given to the availability of local buyers.

Groundnuts

There is a good potential for groundnuts for local consumption and for sale as confectionery nuts to groundnut shelling plants and also for sale to local oil mills. Good seeds of recommended varieties (confectionery or oil purposes) are required. Because of the danger of moulds in the nuts due to poor drying or to inappropriate washing to remove dirt, there is a significant danger of aflatoxins and this must be guarded against.

Groundnut store — Zambia

As with other crops farmers should only be encouraged to grow groundnuts when buyers are likely to be available. The scale of production to be promoted should be based on the availability of groundnut shelling plants, confectionery manufacturers and oil mills which can receive large quantities of nuts. Extension officers can facilitate supplies to larger buyers, especially oil mills, by grouping farmers so as to obtain transportable lots.

Soyabeans

Much has been written about the nutritional aspects of soyabeans. They are an important source of protein and contain calcium, iron and vitamins. However, this crop should only be promoted if a local demand and a local capability to utilize the soyabeans exists. Soyabeans can be used for oil production and the resulting cake is a valuable ingredient in animal feed and in various food products. However, the commercial viability of soyabeans rests on the availability of local factories/oil mills to buy the beans. While there are some small-scale technologies for domestic oil extraction, their introduction should be in conjunction with support from home economists who can teach people how to process and subsequently use the soyabean products.

Other oilseeds

There are a number of other oilseed crops such as sesame (simsim) and sunflower which can be promoted as cash crops if there is a local oil-milling enterprise in the locality. In some countries sesame forms part of the local diet. In Uganda, the oil is used in cooking and the paste left over from the oil-making process is used as sauce. Variety is an important consideration for sunflower, with the black varieties having high yields and high oil content. In Northern Tanzania, a small-scale, sunflower oil press has been introduced. This enables home and village-level processing for domestic cooking oil requirements. It also has the advantage of significantly adding value to the sunflower crop.

There is a reasonable demand in export markets (and in local oil mills) for sesame but commercial exploitation of the crop should be based on the linkage of farmers with exporters and/or with local oil mills.

Cassava

This crop is a staple and drought-resistant crop in many countries and is often grown as a “security” crop. Where production is significant, for example in Southern Tanzania, cassava is sold to processing plants for chipping and export. However, most cassava is produced as a subsistence crop in Eastern Africa and commercial marketing is limited. Once harvested, the crop is very perishable and the low value-to-weight ratio makes cassava uneconomic for long-distance travel. Some varieties have a high arsenic content in their outer skins and require careful washing and peeling before cooking, especially if sold as a cooked product in local markets.

Cotton

Cotton, like maize, has been undergoing significant liberalization of marketing arrangements in recent years. Prior to the early 1990s, most cotton was purchased and ginned by marketing boards or cooperatives. While such an arrangement was not without its problems, notably the high costs of the government marketing agencies, it did have one benefit in that the buyers of the seed cotton were able to supply inputs to the farmers free of charge, secure in the knowledge that farmers had no alternative outlets for their cotton. The situation has now changed and an important consequence of liberalization has been that less inputs, in particular fertilizers and pesticides, are being used.

With marketing liberalization, competition to buy cotton from farmers has pushed prices up in many areas and has encouraged farmers to diversify. As with maize, however, many of the new traders are unknown to the farmers. Extension workers can assist farmers by identifying reputable traders.

In some cases, the new cotton companies may be prepared to fund farmers' input purchases. Extension workers need to develop a climate of trust between farmers and buyers who provide credit because if the buyers think that farmers will not sell to them at harvest time they will not be prepared to extend credit. Where such support for input purchase is not available, extension workers should be able to advise farmers where they can buy the right inputs. One consequence of liberalization reported from Tanzania is that farmers had become used to using pesticides with particular brand names. With liberalization, agro-chemicals with different brand names but containing the same active ingredients are on sale. Farmers are reportedly suspicious of these and are reluctant to buy them. Extension workers can play an important role in explaining to farmers that the newly available pesticides are basically the same as the ones they have been used to.

Transporting sacks of cotton — Uganda