Main points in Chapter 7

Inputs, and paying for them

Impact of changes in input marketing arrangements

When a family saves “in-kind” its wealth is visible and susceptible to theft …

How extension workers can help farmers to

… but if the family saves money in a bank neighbours and relatives are unaware of its assets.

Farmers are often reluctant to save.

Extension officers can emphasize the importance of saving …

… and the best way to save.

CHANGES IN INPUT MARKETING ARRANGEMENTS

For the purpose of this Guide we consider inputs as seed, fertilizer, storage chemicals and bags for grain. There are, of course, many other farm inputs, most notably labour, and mechanical and animal power.

Governments have in the past intervened heavily in the provision of credit to the agricultural sector. Credit often accompanied input packages offered by the marketing boards who in turn deducted the costs from the crop purchased after the harvest. Government and donor subsidies served to keep the cost of production and food prices low but encouraged levels of input use which were economically and environmentally unsustainable. With market liberalization, there has been a movement towards the reduction or abolition of subsidies with the transfer of distribution of agricultural inputs to the private sector (agribusinesses, fertilizer companies, agricultural traders and merchants). However, in some countries the government continues to intervene, thus hindering the development of the private sector in this capacity. In addition, efforts are focused on the liberalization of markets and removal of distortions in trade with little or no attention paid to encouraging a more environmentally appropriate use of agricultural inputs.

At the end of 1997, marketing arrangements for farm inputs had perhaps not changed as much as for maize. It is noteworthy that in Zimbabwe fertilizer has always been supplied by the private sector while seeds for grains have largely been in the hands of the Seed Coop. In Kenya, the private sector has played a leading role in fertilizer and seed supplies for many years. In most other countries, however, marketing boards remained responsible for fertilizer sales (for example ADMARC in Malawi) or were in the process of transferring marketing from the state/cooperative sector to the private sector (for example Tanzania and Zambia).

For most countries, the pattern that is gradually emerging is of private retailers, supplied by private distributors, becoming responsible for input sales. The implications of this for farmers are:

Inputs at a competitive price

It should not be assumed by farmers that, in a town with several input suppliers, the prices of the products they sell will always be the same. Thus, when shopping for inputs it is in the farmer's interest to contact all suppliers to obtain the best price. Reasons for price differences include:

Buying inputs while they are available

In several countries of the region there used to be massive fluctuations in the supply of inputs. In some years the local cooperative or marketing board experienced a shortage of fertilizer, while in others it had far more than farmers needed. As a private-market system of inputs distribution develops, it is probable that a more even supply of inputs will be achieved. The amount of fertilizer in shops will not depend on the efficiency of the marketing board or on how much foreign exchange the government can allocate for fertilizer but on how much each individual retailer thinks he can sell. However, in some countries private sector suppliers are still cautious about the extent of their investment in agricultural inputs due to the fact that they are unsure to what extent the government will continue to interfere in input supply.

Fertilizer and other inputs are expensive and a fertilizer retailer requires a considerable amount of capital. The last thing he wants is to tie up this capital after the period when farmers apply top dressing. If anything, he will be conservative in his estimate of his likely sales, in order to avoid being left with stock which cannot be sold for another nine months. Thus, farmers who delay buying their fertilizer until the last minute, or experience difficulties in making credit arrangements, run the risk that all retailers in town will have run out.

Paying for inputs

Prior to the introduction of structural adjustment measures in many countries, there was excessive government intervention in agricultural credit. Seasonal agricultural credit for maize production to small farmers figured prominently in government budgets. Agricultural banks and specialized agricultural credit institutions, acting as channels for governments and donor agencies, experienced poor loan repayment, rendering them nonviable and leading to their eventual collapse.

In several countries, the former system was that agricultural credit banks gave credit for individual farmers through the inputs marketing board. Where the board or cooperative selling the fertilizer was the same as the board buying the maize or even where they were two different boards, collecting repayment was, in theory, relatively easy. The bank simply advised the maize board of the names of the debtors and the board collected loan repayment when the farmer delivered his maize. In practice, of course, things were often not so simple. A bad harvest meant that many farmers delivered no maize and so the loans were not repaid. Even where there was a good harvest farmers often found ways of avoiding repayment, for example through “third-party” marketing.

A major result of the financial sector liberalization has been the withdrawal of financial institutions from direct lending to small farmers and this has led to an overall institutional gap in rural credit supply. The arrangements for obtaining credit have thus changed considerably. In many countries the situation has already arisen where banks are no longer willing to lend to small-scale farmers, who are seen as a high-risk category. This does not mean that farmers will have no options for funding their input purchases. Firstly, self-finance should not be overlooked. Further, alternative options are beginning to emerge to cater for the financial needs of small-scale farmers including:

As noted elsewhere, farmers could try to save some cash from maize sales or delay selling some maize until they need to buy inputs. As an alternative to selling maize to traders, they could consider bartering it in exchange for fertilizer from input retailers. If they trust a particular retailer, they could establish an account with him, paying in maize or cash at harvest time and collecting the fertilizer when available.

Extension workers could provide assistance to individual farmers and groups in establishing links with formal and semi-formal financial institutions and by providing a list of input suppliers in the area who operate credit schemes, outgrower schemes, or barter arrangements.

It is not sufficient just to improve small farmers' access to finance, they need to be able to manage their money efficiently. This is all-too-often overlooked.

HELPING FARMERS WITH INPUT SUPPLY AND FINANCE

In the same way that extension workers can do much to assist farmers market their maize, there is considerable scope for them to help farmers to obtain necessary inputs. These activities include helping farmers to:

Calculating input requirements

The new marketing arrangements for maize, together with the resulting changes to credit arrangements in some countries of the region, mean that farmers will need to reassess their input needs. In several countries farmers adopted a fairly irresponsible approach to credit repayment, viewing credit as a grant or hand-out and repayment rates were often very low. The fact that there was often no real obligation (apart from a moral one) to repay loans meant that farmers often did not worry too much about whether applying fertilizer would be cost-effective or not.

Times have now changed and easy credit is no longer available. At the same time, it is now more difficult to calculate the economic viability of fertilizer application. In the past, if the marketing board announced the price for maize in advance then the farmer could have a reasonable idea of likely returns from using fertilizer. In fact, the government maize price was often calculated on the basis of the cost of production using fertilizer. Now, the price is not known. If the overall harvest is good, then the price will be low and may not justify the application of fertilizer. If the overall harvest is bad then the price will be high and will certainly have justified fertilizer application if the farmer achieves a normal harvest. But, at times of drought, he may have a very small crop, with no surplus beyond his family's needs.

Ministries of Agriculture in the region need to consider revising recommended application rates for fertilizer to reflect changes in marketing and pricing arrangements for both inputs and outputs. Past “blanket” recommendations for a whole country need to be made more specific to certain areas and soil types, and to reflect relative risks of crop failure. Extension workers should be able to advise farmers of the probable yield increases resulting from fertilizer application, and help them calculate the likely returns, assuming different selling prices for their maize.

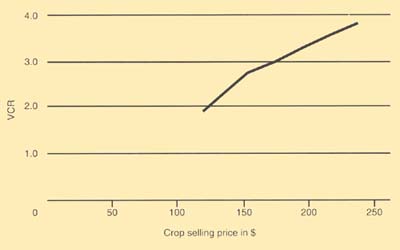

A widely used measure of profitability of using fertilizer has been the Value-Cost Ratio (VCR). This is defined as the sales value of the extra yield produced by using fertilizer divided by the cost of that fertilizer. Normally, a VCR of at least two is considered necessary, although a VCR of this level is risky if there is a danger of drought, disease or crop prices falling. Figure 12 illustrates how the VCR can change as crop prices rise. When the maize price was fixed by the government, calculating the VCR was relatively easy. However, these days it is almost impossible as, at planting time, the farmer is faced with having no information with which to forecast the likely price. The situation is not quite as difficult when top dressing application is required because, by then, the rainfall pattern should be clearer and a rough guess can be made as to whether the harvest is likely to be good or not. In helping farmers estimate the VCR, the extension officer should make sure that the value he uses for maize and the cost he uses for fertilizer is the actual price at the farm gate. That is, transport and other costs need to be deducted from the grain price and added to the fertilizer price.

Figure 12

Changes in value-cost ratio (VCR)

Assumptions: No fertilizer used - yield per hectare 1.5 ton

Fertilizer used - yield per hectare 2.5 ton

Fertilizer application 200 kg

Fertilizer price $350 per ton

Ways in which extension workers can assist farmers in making decisions about input use include:

Where to buy inputs?

Chapter 3 suggested that provincial extension services should consider preparing lists of maize buyers and their prices. At appropriate times of the year such lists should also include information about fertilizer, seed, agrochemical and bag suppliers and their prices. Where there are phones available, extension workers should confirm these prices before farmers visit towns to buy inputs. Information could also be made available about whether traders are able to extend credit or whether they are prepared to barter maize for inputs.

Group transport of inputs

While traders are often prepared to visit villages to buy maize and other crops, input dealers are, at present, rarely prepared to deliver inputs. This situation may change in the future as private input retailers become more financially viable and more confident about the business they are in but, in the short run, farmers will have to continue to organize their own transport. In some cases (for example Zambia) large fertilizer companies have established depots at district level where they offer barter arrangements. Farmers can exchange maize for fertilizer and seed. No cash changes hands but, in the case of Zambia, the exchange of produce must take place prior to release of inputs.

Farmers who organize themselves in groups can combine their resources and purchase their inputs in bulk, whether seed, fertilizer or pesticides, so reducing transport costs and ensuring timely delivery of inputs.

This system is widely practised in Zimbabwe, where village groups pool together to collect fertilizer from one of the two fertilizer factories in Harare. It is an approach which could be adopted by farmers elsewhere in the region and would be more efficient than individual farmers buying a few bags and transporting them home on the roof of a bus. It may also be possible to obtain quantity discounts from the retailers, who would clearly prefer to sell a pick-up full or a truckload at one time, rather than have to deal with numerous small farmers each wanting one or two bags. Organizing group transport is, however, not so easy and this is where the extension worker can play an important role by contacting the transport companies, identifying and negotiating with the retailers and ensuring that the groups of farmers are properly organized.

Helping farmers to obtain credit

Whether trying to acquire a loan or make a deposit in a formal or semi-formal financial institution will require transport, time and in many cases repeated visits. The extension agent, while he should not become involved in “actual” banking practices, related to savings or credit, can provide assistance to farmers in his district, as follows:

by providing lists of financial institutions, private companies, outgrower schemes, and agribusinesses who are engaged in providing credit to small-scale farmers, specifying …

loan terms and conditions, that is interest rates, loan duration and repayment schedule;

Helping farmers to save

Accumulating savings prior to requesting a loan is a valuable educational mechanism to help smallholders appreciate the value of money. Saving even small amounts on a regular basis instils a disciplinary effect on the saver. The idea that small-scale farmers have a poor saving capacity, and consequently a poor demand for savings deposit facilities, is untrue. Farm households can and do save and if they have access to appropriate savings instruments and stable financial institutions (where savings can be considered “safe”) they ought to be encouraged to save in monetary terms rather than in-kind.

It is widely recognized that access to savings deposits and money transfer services is just as vital as access to loans. In any given community, there are likely to be four or five times as many savers as there are borrowers. Access, security, maintenance of value and investment return are all important for the depositor. However, there is often a lack of appreciation among small farm households of the potential of local savings to fund investments. Encouraging small farmers to save will foster investment in rural areas. Extension agents also need to emphasize the importance of using savings to purchase inputs for the following season.

When a small-scale farmer saves money, his primary concern is that of safety. An important question which an extension worker must try to answer is whether the local financial institutions are safe. If such an institution collapses, it will result in a long-lasting mistrust towards the idea of saving.

When a farmer saves “in-kind”, whether in livestock, grain or other farm products, his “wealth” is visible to the community and, in addition, more susceptible to theft and damage. Financial savings, when safe, eliminate the risk of loss and neighbours, relatives and friends are unaware of the farmer's assets and therefore less demanding.

Ways in which the extension agent can assist farmers to save include:

provide advice on available financial institutions …

access to savings (for example a demand deposit is payable on demand and requires no prior notice of withdrawal, generally such deposits earn a low rate of interest. Term deposits are payable after a predetermined period of time and generally earn higher rates of interest);

advise individual farmers and groups on savings accounts that best suit their situation, considering production costs, production patterns and household needs.

Experience has shown that savings clubs have worked well and have been highly successful among small-scale farmers in Zimbabwe. Groups have voluntarily agreed to club together to ensure access to cheaper inputs by buying in bulk at a discounted price. Such clubs have maintained a savings account with a bank, building society or post office savings bank, thereby earning interest (which covers the administration costs of the club and transaction costs) on their savings and eliminating the threat of loss or theft.