This manual addresses a situation where rinderpest invades a country, or a zone within a country, which was formerly considered free from rinderpest. Should such an emergency occur, all initiatives should be directed at rapid containment of the disease in the primary focus or zone and eradication within the shortest possible time to avoid spread and possible progression to endemic status.

There are a number of epidemiological and other factors that are favourable to eradication of rinderpest:

However, rinderpest eradication can sometimes be complicated by:

When dealing with a rinderpest emergency, one of the first steps should be to delineate zones for purposes of containment and elimination of the disease, irrespective of which control option is to be adopted. It is suggested that two zones, an infected zone and a surveillance zone, be delineated.

Infected zone

This is a clearly defined area in the country surrounding the herd(s), premises, villages or settlements where clinical rinderpest has been detected or where a high risk of contamination is known to have occurred. It will include all herds/settlements that have received susceptible species of animals from an infected herd in the 21 days before rinderpest appeared in the herd of origin. The OIE guidelines recommend a 10-km radius around the disease centre(s) in areas where intensive livestock management is practised, and a 50-km radius in areas where extensive husbandry is practised. The infected zone will therefore include herds, premises and villages where clinical cases have been identified, as well as high-risk contact areas (dangerous contact premises). The infected zone should be the smallest size that is consistent with effective disease containment and OIE guidelines. In deciding its shape and size, consideration should be given to topographical features, physical barriers, administrative borders and the resources available for enforcement and surveillance.

Surveillance zone

This is the area surrounding the infected zone. Its size will depend on realistic assessment of the resources available for surveillance.

Three options for dealing with a rinderpest disease emergency should be considered:

Stamping out by slaughter is the preferred option in:

Modified stamping out with ring vaccination may be preferred for:

Quarantine and ring vaccination without slaughter may, on the other hand, be the preferred option in countries where:

This option is designed to contain an incursion of rinderpest so as to eliminate it in the shortest possible time. It requires intensive surveillance, immediate quarantining of infected herds, imposition of strict movement controls and slaughter of all susceptible species of animals in infected premises, with immediate payment of fair compensation for slaughtered animals. This is certainly the most desirable strategy for rapid elimination of introduced rinderpest and is the most cost-effective option.

The advantage of complete herd slaughter is that it eliminates very rapidly the source of infection for other animals. Indirect transmission is unlikely as long as carcasses are disposed of safely. After slaughter, meat and meat products rapidly become insignificant as regards disease transmission. Disease tracing and enhanced surveillance will be required to determine the origin and extent of infection, so that adequate zones can be declared for rinderpest control purposes and, subsequently, to assist in proving regained freedom from the disease and infection.

The essential elements of stamping out include:

• slaughter of clinically affected, suspected and exposed susceptible animals in the infected herds/

premises/settlements within the infected zone;

• safe disposal of carcasses;

• decontamination;

• quarantine and movement restrictions;

• tracing and surveillance;

• awareness campaigns;

• restocking at least 30 days after cleaning and disinfection.

Actions to be taken in the infected zone

Quarantine. Movement of susceptible livestock species out of the infected zone should be prohibited. One exception could be the movement of apparently healthy animals from non-affected premises direct to an abattoir for slaughter. This must be done under strict zoosanitary control. It may also be necessary to transport animals to a site of destruction and disposal within the infected zone. Movement of susceptible animals into the zone is prohibited or subject to special permit. Restrictions should be placed on human and vehicular traffic in and out of the zone, and any movements should be subject to proper cleaning and decontamination on exit.

Slaughter and disposal. All susceptible livestock species in the infected premises should be slaughtered, whether clinically ill or not. The carcasses should be disposed of by burying or burning. Fair compensation should be paid as soon as possible, preferably at the time of slaughter.

Decontamination. Depopulated premises, equipment, clothing and other protective outfits in dairy animal housing and feedlots should be cleaned with detergents/soaps and then decontaminated with oxidizing agents such as sodium or calcium hypochlorite and alkalis such as sodium hydroxide or sodium carbonate.

Faeces and effluents should be treated with sodium carbonate, which is effective even in the presence of organic matter, before burial or burning.

Dangerous contact premises. These are premises in the area immediately surrounding the infected premises/herds/villages in which epidemiological investigations show high likelihood that rinderpest infection may have been introduced, although no overt disease has yet been seen. They include premises elsewhere into which cattle or other susceptible animals have been introduced from infected herds during the critical period. Such premises should be placed under strict quarantine and subjected to intense active surveillance. If any infected animal is detected, the area is automatically considered to be infected premises. All such holdings, premises, villages or settlements with susceptible species of livestock should be visited daily to examine the animals for clinical disease. This must continue for at least 21 days after the last clinical case has been slaughtered in the infected premises.

Surveillance. A though epidemiological investigation should be carried out in the infected zone to define the source of infection and to detect other possible primary introductions and onward spread. Tracing forwards and back wards is essential to determine where the virus came from and to discover any secondary outbreaks which might have resulted from movement of animals from infected premises.

Where a significant wildife population exists and there is a risk of rinderpest introduction, active disease surveillance and serosurveillance should include wildlife. This will involve serological surveys and close monitoring of morbidity and mortality in susceptible wildlife, requiring close collaboration with the wildlife authorities.

Standstill order. A standstill order should be imposed and enforced in the infected zone, if necessary with active support from military and police authorities. It must apply to all susceptible livestock species for a minimum of 21 days after slaughter of the last clinical case, assuming disease surveillance is effective. It should include closure of livestock markets and cancellation of all livestock events during the period. Ideally, abattoirs and slaughterhouses/slabs should be prohibited from slaughtering susceptible livestock species in the area. It may be necessary to provide an alternative supply of meat.

Abattoirs can safely recommence operations not less than 21 days after the last affected animal has been slaughtered, assuming that disease surveillance is effective. Prolonged prohibition carries the risk that the community will develop alternative means of slaughter, which may render planned control efforts ineffective. Milk should be heat-treated to destroy any virus.

Actions to be taken in the surveillance zone

Within the surveillance zone, all holdings (premises, villages or settlements) with susceptible livestock species should be visited weekly to examine the animals for clinical disease. This must continue for at least 21 days after the last clinical case in the infected zone has been slaughtered. Movement out of the zone must be by special permit after clinical examination of all animals in the herd/premises, but movement of susceptible livestock species into the zone is allowed. Risk enterprises such as dairy and meat processing plants are allowed to operate, subject to a high level of hygienic practice in all stages of their operations. Additional information on these aspects may be found in the enterprise manuals of the AUSVETPLAN on:

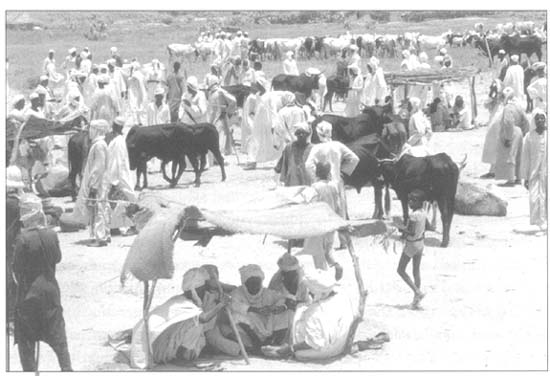

CATTLE MARKET

Closure of cattle

markets should be a

part of a standstill

order in the infected

zone during

rinderpest

emergencies

Proof and verification of rinderpest elimination

Elimination of rinderpest will be verified when active rinderpest surveillance shows that there are: no new cases of clinical disease occurring; no seroconversion in cattle or other susceptible species in the infected and surveillance zones; and evidence of effective veterinary infrastructure. For disease investigation and surveillance, it will be necessary to:

Additional details of procedures for disease and serological surveillance can be found in the Recommended procedures for disease and serological surveillance as part of the global rinderpest eradication programme (GREP), FAO/IAEA TECDOC, Vienna, 1994.

According to the OIE International animal health code (1999), for rinderpest: “… should there be a localized rinderpest outbreak in an infection-free country, the waiting period before infection-free status can be regained shall be as follows: six months after the last case, where stamping out without vaccination and serological surveillance is applied.”

Acceptance of renewed freedom will require intensive active disease surveillance in the infected and surveillance zones using repeated disease search and other epidemiological survey techniques. Case finding should include the use of carefully designed questionnaire surveys with ensured community participation.

Evidence will be required that the following investigations and activities were carried out:

Where wildlife species are relatively numerous and have been implicated in previous rinderpest incidents, active disease surveillance must include efforts to investigate thoroughly any possible morbidity and mortality in these species.

If total eradication is not a feasible option, modified stamping out can provide rapid control of an outbreak. This consists of the immediate imposition of strict movement controls, slaughter of clinically affected animals in the infected herd (s), premises, villages or settlements, combined with ring vaccination of in-contact as well as other susceptible livestock in the infected zone. The term “modified stamping out”, according to the International animal health code, is used whenever stamping out, measures are not implemented in full. Details of modifications should be given.

This option is designed to reduce the number of infected animals shedding virus and the number of susceptible animals. It creates, in the area surrounding the infected herds, a ring of immune animals protected from the risk of developing rinderpest after exposure from the known infected herds or from an undetected source.

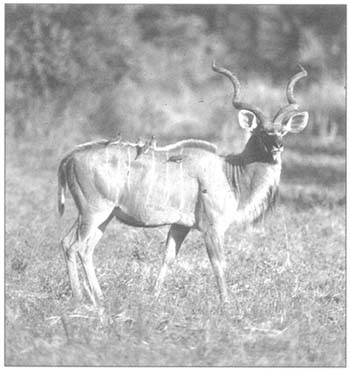

KUDU

Active disease search and serosurveillance should

include susceptible wildlife species

These aims can be achieved relatively quickly. Within one week from vaccination, animals respond with a serviceable degree of immunity. Animals incubating rinderpest at the time of vaccination must be expected to develop clinical disease, so fresh clinical cases are to be expected for up to 21 days after vaccination has been completed, even if vaccination has been 100 percent effective. Virus shedding from these animals ceases within another 14 days, making a total of 35 days.

The essential elements of this strategy

include:

• slaughter of clinically affected animals and

suspects in the infected herds/premises;

• immediate ring vaccination and identification of

vaccinates;

• quarantine and movement control;

• tracing and surveillance to determine the source

and extent of infection;

• an awareness campaign to promote the cooperation

of livestock owners and the general

public;

• proof of elimination;

• eventual slaughter of affected animals, if this is

realistic for export trade purposes.

Countries that do not export livestock and livestock products may wish to note that vaccinated animals are solidly immune and do not become unapparent carriers. They could be retained without risk of compromising eradication and serosurveillance, as long as they are permanently identifiable.

Actions to be taken in the infected zone Quarantine. Strict movement controls should be imposed on all susceptible livestock species in the infected zone. Susceptible animals in this zone should be vaccinated.

Slaughter and disposal. Clinically sick animals should be slaughtered to reduced virus shedding, thus minimizing the risk of transmission within and from the herd. Carcasses of dead and slaughtered animals should be buried or burnt on the premises or at a nearby site accessible to the infected premises/area.

Vaccination. All in-contact animals in the affected herds and other herds in the infected zone should be vaccinated. Although a number of countries produce their own vaccines, it is important that a source of high-quality vaccines conforming to OIE standards is identified in advance. These vaccines may be conventional or thermostable versions of the tissue-culture rinderpest vaccine. In future, other novel types such as recombinant vaccines may become available for field use.

The vaccination programme must be structured. At least two independent vaccination teams are required to work in the infected zone. The first vaccinates the remaining members of the infected herd or herds, of which a proportion will be incubating the disease. The second undertakes vaccination of surrounding herds in a ring around the infected herd(s), premises or settlements in the infected zone, starting from the outside of the ring and working inwards. The size of the ring should be determined by the ability to complete vaccination within one week or less. It is better to define several rings to be vaccinated successively, starting with the area at highest risk, than to have one ring which takes an excessively long time to complete.

Affected herds should never be assembled with neighbouring herds at communal crushes for vaccination, as this greatly increases the risk of transmitting infection, both within the infected zone and to herds in the surveillance zone often. It is often expedient to consider an entire community, centred on a village and perhaps sharing a common watering-point, as an infected herd. Attaining a sufficiently high level of herd immunity might require a second round of vaccination within four to six weeks. Vaccination coverage needs to be monitored closely. The target should be to raise the herd immunity levels to above 75 percent.

It is necessary to identify the vaccinated animals permanently, for example by earnotching, so that their presence will not compromise later serosurveillance studies required for demonstrating freedom from infection. Such vaccinated animals need to be identified for slaughter at the stage of seeking OIE approval for return to rinderpest-free status for export trade purposes.

Standstill order. This should be imposed within the infected zone. For it to be effective, police or military enforcement may be necessary. Closure of livestock markets, abattoirs and slaughterhouses in the infected zone should remain in force for at least 56 days after vaccination has been completed. It might be necessary to provide alternative sources of meat or to consider moving animals for slaughter under escort. Restocking with susceptible livestock should not be done until at least 56 days after the last clinical case has been slaughtered or vaccination has been completed, whichever is the later. Adequate public awareness campaigns should be carried out.

Surveillance. Within the zone, all premises, villages or settlements with susceptible livestock species should be visited daily to examine the animals for clinical disease. This must continue for at least 21 days after the last clinical case has been slaughtered or vaccination has been completed, whichever is the later.

Actions to be taken in the surveillance zone

This area surrounds the infected zone. Its size will depend on a realistic assessment of the resources available for enforcement and surveillance. Within the zone, all livestock holdings (premises, villages or settlements) with susceptible livestock species should be visited weekly to examine animals for clinical disease. This must continue for at least 21 days after the last clinical case in the infected zone has died or has been slaughtered or until vaccination has been completed, whichever is the later.

In some circumstances, a sanitary cordon consisting of a buffer zone and a surveillance zone would be needed to separate a rinderpest-infected area from a rinderpest-free one. Susceptible livestock species may move into the buffer zone but must remain for at least 21 days. To prevent secondary outbreaks of rinderpest, susceptible livestock species in this zone should be vaccinated if transiting animals develop the disease.

The surveillance zone of the sanitary cordon is subjected to a high level of disease surveillance but no rinderpest vaccination is carried out.

Slaughter of vaccinated animals

After the disease has been eliminated and repeated active disease search and serosurveillance confirm absence of rinderpest infection, the country may wish to seek OIE verification of freedom from infection in order to regain its former status as a rinderpest-free country. For countries that are involved in international trade in livestock and livestock products, which may require rinderpest antibody-free status, it will be necessary to slaughter vaccinated animals when the disease has been eliminated and active and serological surveillance confirm freedom from infection.

Proof and verification of rinderpest elimination

The International animal health code (1999) states: “Should a localized rinderpest outbreak occur in an infection-free country, the waiting period before infection-free status can be regained shall be as follows: six months after the slaughter of the last vaccinated animal where stamping out complemented by emergency vaccination (vaccinated animals should be clearly identified with a permanent mark) and serological surveillance are applied.”

Acceptance of renewed freedom will require active disease surveillance and other epidemiological survey techniques as described under option one.

Should a localized outbreak of rinderpest occur in a zone within a rinderpest-free country and stamping out by slaughter is not possible, the country may with to carry out limited emergency vaccination of susceptible domestic livestock in the zone. Two rounds of vaccination within six months (immunosterilization) should be carried out.

The essential elements of this option

include:

• immediate quarantine and movement control

in the infected zone;

• ring vaccination and identification of vaccinates;

• disposal of carcasses of dead animals and

decontamination;

• Tracing and surveillance to determine source

and extent of the infection;

• awareness campaign;

• proof of elimination.

The activities to be carried out under this option are similar to those described above in the section on modified stamping out and vaccination, except that there is no slaughter of affected livestock species.

Carcasses of animals that die from the disease should be properly disposed of by burying or burning. It is very important to mark vaccinated animals permanently, to assist in the interpretation of subsequent serological surveys.

Proof and verification of rinderpest elimination

It will be necessary to carry out seromonitoring of the vaccinated animals to confirm herd immunity levels. Repeated active disease search and serosurveillance in all susceptible livestock and wildlife species should be carried out in the infected and surveillance zones.

The OIE International animal health code (1999) provides that the waiting period before infection-free status can be regained shall be 12 months after the last case or last vaccination (whichever occurs later) where emergency vaccination without slaughter (vaccinated animals should be clearly identified with a permanent mark) and serological surveillance are applied.

Special provisions will be made for rinderpest control and elimination in relatively inaccessible areas and under a transhumant or nomadic system of husbandry. Special strategies have to be designed to overcome the major constraints and to ensure farmers' confidence in planned control measures. Some of the methods that have yielded positive results include:

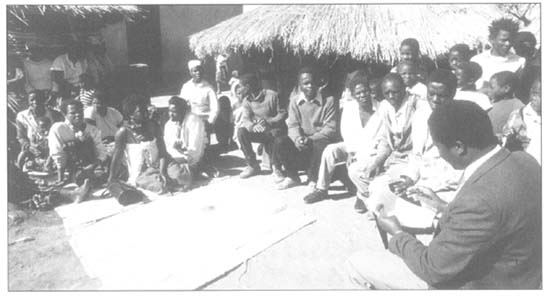

COMMUNITY

DIALOGUE

Discussions and

consultations with

livestock owners/

local community on

disease control

arrangements

It is unlikely that an outbreak of rinderpest would not be eliminated if it were detected and responded to in time. However, if the size of an outbreak outstrips the resources available for control and ring vaccination is unable to arrest the spread, the affected country would have to revert to a policy of mass immunization. This would be targeted at known and suspected infected areas together with areas considered to be at high risk for spread of the disease, such as livestock movement routes. The aim should be to carry out several rounds of vaccination over one or two years and then to discontinue vaccination once the disease had been eliminated. Blanket vaccination of the entire susceptible population will be carried out and the effectiveness of vaccination monitored serologically.

If there are significantly large areas of the country that can still be regarded as uninfected, the country may establish a sanitary cordon to separate the infected from the free areas. This is a belt of two zones, a buffer zone and a surveillance zone, separating a rinderpest-infected area from a rinderpest-free area.

Susceptible livestock species may move into the first belt of the buffer zone under veterinary supervision. All susceptible livestock in this zone will be vaccinated to prevent occurrence of any secondary outbreaks. The second belt of the sanitary cordon, the surveillance zone, is subjected to a high level of disease surveillance without vaccination of resident susceptible livestock.