|

GENDER AND PARTICIPATION IN AGRICULTURAL DEVELOPMENT PLANNING |

PLANNERS THROUGHOUT AFRICA, ASIA, LATIN AMERICA and the Near East are increasingly called upon to use methods that are participatory, that are bottom-up, and that will benefit women as well as men. But this rarely happens, mainly because it simply is not clear just how to conduct participatory planning or how to change current planning procedures to make them more responsive to gender and other differences among farmers.

But the experience of the From Farmer to Planner and Back: Harvesting Best Practices workshop shows that progress is being made. There were 12 FAO projects represented, each actively involved in testing and/or using participatory planning tools and methods to find solutions for diverse agricultural development needs. Gender needs were also recognized, in the sense of ensuring that both women and men had a voice in the planning exercise and that their needs were recognized.

The projects were from all regions of the world and covered the gamut of development sectors, including agriculture, livestock, fisheries, forestry and rural development (the list of projects and their locations is on the next page). Their common link was the focus on gender and participation.

The workshop organizers recognized that in order for the participants to get the full value of their workshop experience, they needed an understanding of how their work fit within a global picture. Case studies were commissioned from each project, with authors asked to follow prescribed outlines which would give an overview of the projects themselves, the types of tools and methodologies being used, the levels of success or degrees of problems encountered. The hope was that by sharing this information, other participants as well as other interested groups could learn from the trials and errors.

Each of the case studies included: i) an overview of the national situation, including geographical and historical information as well as information about the policy environment for agricultural development, gender and participation; ii) a project summary, including its objectives, rationale and strategy; iii) a chronology of important activities and how they were implemented; and iv) lessons learned, including a critical analysis of what contributed to the shortcomings and successes of the project, with a focus on the gender-participation-planning nexus.

Within the "lessons learned" segment, the case studies reported specifically on six inter-related areas: the entry point at which the project became involved in the agricultural planning process; the tools and methods used; capacity-building, especially training in gender analysis and participatory methods; the gender information produced; the linkages with planning processes and related organizations; and institutionalization.

This paper reviews ten of those case studies, from the projects listed below, and provides an analytical overview of the roles of gender and participation in planning. It provides specific information on the good practices and problems revealed by the case studies, with the hope of promoting a wider dialogue on how best to pursue the goal of increasing responsiveness of agricultural planning to the priorities of different groups of farmers, women and men alike.

Ethiopia "Improving Client Oriented Extension Training in Ethiopia" (GCP/ETH/051 /NET)

Namibia "Improving Information on Women's Contribution to Agricultural Production for Gender Sensitive Planning" (GCP/NAM/005/NOR) and "Training for the Integration of Women in Agriculture and Rural Development" (TCP/NAM/ 4451/NAM)

Senegal "Reboisement villageois dans le Nord-Ouest du Bassin Arachidier" (Previnoba) (GCP/SEN/029/NET)

India "Development of Small-Scale Livestock Activities in Sikkim" (TCP/IND/ 4451(A))

Nepal "Improving Information on Women's Contribution to Agricultural Production for Gender Sensitive Planning" (GCP/NEP/051/NOR)

Costa Rica "Apoyo a las Mujeres Productoras del Area Rural en el Marco de un Enfoque de Genero" (TCP/COS/4552 (T)

Honduras "Apoyo a la Mujer Rural Para su Acceso a Recursos de Producción" (GCP/ HON/017/NET))

Afghanistan "Promotion of Farmers' Participation through the Implementation of Animal Health and Production Improvement Modules (AHPIM) in Afghanistan" (TCP/AFG/4553(T))

Pakistan "Participatory Upland Conservation and Development" (GCP/INT/542/ITA)

Tunisia "Définition d'une politique et elaboration d'une stratégie et d'un Plan d'action en faveur des femmes rurales" (TCP/TUN/4555)

This section provides background information for discussion of the case studies by briefly describing the major processes involved in agricultural planning and by explaining what "gender- and difference-sensitive participatory agricultural planning" actually means.

Although there are important linkages between agricultural policy-making and agricultural development planning, the two are quite distinct. This paper focuses on agricultural planning.

Who is involved?

Agricultural planners develop national, regional and district plans, programmes and projects that are compatible with the goals, strategies and policies set by policy-makers. Planners may be economists, social scientists or technical specialists employed in the planning units of ministries of agriculture or their various line agencies, such as extension or livestock services, or in national or international development non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and agencies. Managers may also be involved in planning, especially in programme planning for line agencies.

In addition to governmental institutions, planning takes place in international organizations (e.g. FAO) as well as in private agencies, NGOs, commercial establishments and on individual farms. Thus, to some extent, everyone involved in the agricultural sector is a planner. Nonetheless, to be clear, in this paper the term "planner" is reserved for government planners.

Stakeholders are all the people and organizations who stand to gain or lose from a particular policy, programme or project. They are all actors and interest groups in the agricultural sector who are not planners. Many people and groups have a "stake" in the results of agricultural planning, including men and women farmers from different socio-economic, ethnic or age groups, livestock owners, commercial farmers, agricultural wage labourers, fishers, employees and owners of agricultural processing or marketing enterprises, farmers' organizations, elected officials, civil servants and representatives of international agencies.

Farmers, as referred to in this paper, are men and women who engage in small-scale, livestock, crop and fish production and processing as their primary economic activity and who have limited land, capital, educational and labour resources.

How has agricultural planning evolved?

In the 1960s and 1970s, macroeconomic national planning was heavily promoted and widely practised. National plans set growth targets, broke them down by sector, analysed macroeconomic constraints on growth, and developed national and sectoral strategies. Large-scale public, parastatal and private-sector projects were often included in the ubiquitous five-year plans, but projects were rarely planned in detail since their funding was usually not assured. The lack of planners trained in project preparation was an important constraint on overall agricultural planning (FAO, 1984: 8). Large projects were often included in a plan specifically to attract international financing.

National and agricultural sector plans often included price, input, research and extension policies designed to promote rapid economic growth. The emphasis on growth kept the focus on better-endowed regions, large commercial enterprises and export sectors, sometimes exacerbating regional and local income inequalities and often failing to alleviate poverty (Labonne, 1988; FAO, 1985). The smallholder subsistence sector was generally neglected.

This situation changed in the 1970s when major donors began to favour a new breed of integrated rural development (IRD) projects. IRD projects included both social and economic activities and usually focused on the smallholder sector, sometimes even on subsistence-oriented farming systems. The major objective, however, was still to increase the amount of marketed output. Nonetheless, there was a new focus on targeting specific population groups - the poor, the landless, women and the young - with a wide array of services. In some cases, especially in Latin America, these groups were expected to participate in the design of the services they needed (Young, 1993: 47). In most cases, however, participation was not carried down to the village level, and most "services" targeted at women were related not to their productive activities, but to health, education, water supply, etc. - in other words, to their reproductive concerns.

A new form of rural development research, the farming systems research and extension approach (FSR/E), was also developed in the late 1970s and early 1980s, bringing a call for interdisciplinary and more participatory methods to the agricultural research establishment. The impact of FSR/E on agricultural planning and on major agricultural sector projects was, however, limited. This was because most large-scale agricultural projects either targeted or worked mainly with so-called "progressive farmers", who were almost invariably better-off male smallholders or larger commercial farmers. Furthermore, FSR/E was rarely able to integrate all members of the farming household into its analysis or to consider male-female relations at the intra- or interhousehold level (Young, 1993: 52).

Feminist critics of male-biased development projects found inspiration in the FSR/E approach for their work in developing gender analysis. So did the proponents of participatory methods who were seeking ways to make project planning more "bottom-up" (Young, 1993: 47-48). This resulted in the beginnings of gender and agricultural literature and gender and planning literature, as well as the beginnings of a process that was to transform many of the methods and tools of rapid rural appraisal (RRA) into a method that became known as participatory rural appraisal (PRA).

In the 1970s, concern with both poverty and inter-regional disparities also led to the emergence of decentralized, area-based agricultural planning (regional and/or district planning), beginning in India and other parts of Asia in the 1970s and moving to Africa and other parts of the developing world in the 1980s (FAO, 1985; Labonne, 1988). The objectives of area development planning are combined growth and poverty alleviation, and regional "balance" or equity. Participatory planning methods, however, have rarely been used in decentralized planning processes. National plans and projects, regional and district plans, and IRD projects have all usually been developed in a top-down manner (Maetz and Quieti, 1987; Belshaw, 1988; Bendavid-Val, 1990 and 1991).

The debt crisis of the 1980s shifted the emphasis of government policy (with considerable encouragement from international creditor agencies) back to growth, which was pursued by focusing development efforts on regions, farm enterprises and crops with the highest "growth potential", i.e. private-sector commercial agriculture and export crops. This time, however, growth was to be pursued by changing the structure and reach of the government itself, specifically by reducing government involvement and shifting many of its functions to the private sector. Thus, demands for stabilization and structural adjustment, led by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, resulted in widespread reductions in government budgets and staff. Major efforts at national planning were discouraged.

The resurgence of policies that favoured commercial and export agriculture again exacerbated disparities among regions and households. Eventually, the serious negative effect that many "adjustment" policies had on the poor was recognized. This stimulated interest in local area planning and generated proposals for microprojects to alleviate poverty. Among the methods advocated to plan both medium- and small-scale area-based projects were RRA (Conyers, 1993: 108-9) and, more recently, PRA.

RRA methods involved consultation mainly with village leaders and local informants from district line agencies, resulting in a strong male bias. The same was true of early efforts to use PRA, although this situation is changing. However unintentional, a male bias has also permeated in regional and district planning (Maetz and Quieti, 1987: 37-8; Bendavid-Val, 1990: 7 and 1991: 49).

By the late 1970s, it had become clear that growth-focused policies and projects had negative effects on women and this produced a feminist critique that was soon extended to a comprehensive critique of planning itself (Palmer, 1979; Buvinic, 1986). The critique was often accompanied by suggestions for new approaches to planning, complete with a set of tools for gender analysis and gender-sensitive planning (Overholt et al., 1984; Poats et al.,1988; Young, 1988; Feldstein and Poats, 1989; Ostergaard, 1992; Moser, 1993; Young, 1993). The projects represented at the workshop drew both inspiration and methods from this work.

During the 1980s, increasing concerns about poverty and the need to understand its effects on local communities led to a reworking of RRA methods and the development of a new set of planning tools called PRA.1 The feminist development community quickly realized the power of PRA methods for highlighting gender issues and in the 1990s produced the PRA gender analysis literature (Feldstein and Jiggins, 1994).

Mainstream agricultural planning literature, although it promotes decentralized area planning for poverty alleviation and participatory methods for better integration of local priorities into area plans, has rarely taken gender-focused literature into account (FAO, 1986; Maetz and Quieti, 1987; Belshaw, 1988; Bendavid-Val, 1990 and 1991). A few works mention the importance of women, but do not integrate gender into the body of analysis or into the methods advocated. Similarly, "women's components" have often been attached to projects that otherwise ignore gender issues.

In fact, gender analysis has rarely, if ever, entered the planner's tool kit. Neither has PRA, except in a very limited way that tends to confine participation to the official village leadership. In agricultural planning, decision-makers and senior planners have been far more highly trained in the technical aspects of projecting supply and demand, setting targets and allocating resources, than in taking account of socio-economic and gender differences among farmers. The case studies confirm that many people from the older generation of decision-makers are sceptical of bottom-up planning and especially of the need to integrate gender analysis into agricultural planning processes. Several case studies remarked that agricultural officers and field workers had never previously been exposed to either PRA or gender analysis.

The projects described in the case studies demonstrated the relevance of these tools for gender-responsive planning. The next challenge is to work out how to adapt planning procedures so that they are more responsive to the information these tools can generate.

What are the different types of agricultural planning?

The structures, processes and relative importance of the different levels of planning vary from country to country. Any project attempting to work with a particular system needs to study it in its local context. Nevertheless, a basic familiarity with the common features of most agricultural planning systems helps to determine where and to whom the information produced by gender-sensitive participatory processes can be directed in order to increase planning's responsiveness to gender and other differences among farmers.

Development planning, including agricultural planning, can be divided into two basic categories: centralized and decentralized. In a centralized planning system all major policy, planning, programming and budgeting decisions for the sector as a whole and for subsector line agencies are made at the national level. In a decentralized system, responsibility for a large number of planning, programming and budgeting decisions is devolved to regional and/or district levels. A separate regional or district planning apparatus may be formed to develop an area-based investment plan. The decentralization of planning and agricultural administration tends to bring problem analysis and planning closer to regional and local realities.

The decentralization process is of particular relevance to participatory planning. It is spreading geographically (particularly in Africa) and intensifying in areas where it is already established (parts of Asia and Latin America), and decentralization is often introduced with the explicit goal of increasing farmers' participation in planning.

In a decentralized system, the national level focuses on setting goals and targets and on formulating agricultural policies to guide government agency programming and project planning and to influence decision-making in the private sector. National planners also provide budgetary and technical support and coordination, as well as monitoring and evaluation services, for lower levels of planning. They are often involved in designing large-scale projects at national and regional levels.

Regional or area planning is the middle level of a decentralized planning system. This is where plans and programmes initiated at lower levels are brought together and coordinated and where attempts are made to reconcile them with the policy and budget constraints set at the national level. Regional planners may also be involved in the design and implementation of nationally designed projects operating in the region. Regional planners usually provide technical and administrative assistance, as well as training, for district planners and institutions involved in local planning and project development.

District planning takes place in subsector line agencies, as does district extension programming, and in multi-agency institutional or community settings where local projects are designed and implemented. At this level, elected local councils, NGOs, private and farmers' organizations often participate in project and programme planning alongside district planners and line agency technicians. In the past, the lack of funding for more independent programming and planning at local levels has inhibited district planning but, as government administrative decentralization is increasingly pursued, more funding decisions are being passed down to regional and district levels. A more binding constraint on local area planning, especially on IRD planning (which may involve crops, livestock, natural resource management, research, extension, credit, marketing and social sectors in a single project) has been the lack of experience in working in multidisciplinary teams and a lack of appropriate planning methodologies (Maetz and Quieti, 1987).

Village- or community-level planning is still rare. As decentralization takes hold, however, village planning is likely to become increasingly important. It has two basic functions: providing information for higher planning levels by means of participatory problem analysis; and setting community priorities and action plans that can be carried out either independently or with outside assistance. But decentralized planning brings with it new constraints, approaches and demands.

Not all of these elements are present in every country, and they may not necessarily be new in every context, but they are common enough to constitute a relatively new planning environment. And this new environment is conducive to participatory agricultural planning that responds to gender and socio-economic differences.

Planning must become more participatory for several reasons. Among the most compelling is the failure of many development projects and programmes to meet their objectives when farmers do not respond as expected. The old habit of blaming farmers' ignorance and backwardness has lost its appeal, especially as it is now clear that many farmers, including the resource-limited, many women farmers and some pastoralists, face constraints that make it impossible for them to respond as expected. In addition, the success of community development programmes based on participatory planning, implementation and monitoring processes has demonstrated that rural communities are interested in development and will work to make plans and projects succeed as long as those plans respond to local priorities. Finally, the push for democratization has added an important political dimension to the demand for more participatory, bottom-up planning.

The increasing importance attached to taking women into account also stems, in part, from the mediocre performance of projects that ignore women's roles in farming systems. Two decades of gender-sensitive project evaluation has resulted in a growing recognition that many projects, while improving men's situations, actually made women worse off. Other factors have gradually shifted attitudes at both international and national levels, among them pressure on donors and governments to respond to women's needs as farmers, and the momentum created by the major international conferences on population, the environment and women. The rapid expansion of women's organizations throughout the world and their growing links with one another have added a political thrust to this issue.

A far less positive factor in the current environment is the often extreme pressure on governments to reduce their budgets in order to meet structural adjustment and stabilization targets. This factor has an impact at many levels, from the cutting of planning funds and personnel, to the prioritizing of "men's" export crops and the restriction of funds for government services such as extension, marketing and credit for women farmers. This means that great attention must be paid to cost-effectiveness in generating and using information that can promote gender-responsive policy, programme and project development.

Decentralization and agricultural planning | ||

DECENTRALIZED PLANNING AFFECTS THREE MAIN ELEMENTS OF AGRICULTURAL PLANNING: | ||

new constraints, especially the reduced availability of operational funding and the loss of staff by many government agencies as a result of structural adjustment; |

new approaches, including government administrative decentralization and regional and district interdisciplinary planning; and |

new demands, for participation, bottom-up planning and taking women into account. |

Although this new planning environment has, in many places, evoked a positive political response, planners are still faced with the question: What exactly should be done? There are no easy answers, but there are already promising new approaches for involving different groups of farmers, including women and the poor, in agricultural planning. The projects described in the case studies demonstrate the relevance and usefulness of several of these new gender- and difference-sensitive participatory approaches.

What is Participation?

The term "participation" is open to very broad interpretation - even within a single agricultural planning process, different stakeholders may give it different definitions. Participation does not always involve all stakeholders, and may be limited to certain groups (or "levels") within a community. An FAO study of multilevel planning for agricultural development in Asia and the Pacific (FAO, 1985: 89-90), for example, found that participation took place at a number of different levels:

1) participation limited to elites (mostly elected representatives);

2) participation in which people are asked to legitimize or ratify projects that have been identified and formulated by government, but do not participate in the detailed planning and management of the project;

3) participation in which people are consulted from the very start and take an active part in the planning and management of projects;

4) participation in which different social and occupational groups are represented in all planning, coordination and evaluation mechanisms devised at all levels, including the highest policy-making level; and

5) participation in which the representatives in 4) actually control the decisions at all levels.

The FAO study points out that, as of 1985, "experience in the various countries shows that the modes of participation in 4) and 5) have not effect-ively materialized" (ibid. p. 90). While this may no longer be strictly true, participation even at level 3) is still quite rare. Planning projects that promote participatory agricultural planning need to analyse current levels of participation in order to understand the changes that will be required to reach higher levels. The exact meaning of "participation" also needs to be clearly defined.

Tools for participation | ||

Participatory rural appraisal: a set of tools that facilitate a research and action process managed by the local community. It is an exceptionally relevant and powerful way of involving communities in the information generating, analysis and priority setting phases of agricultural planning. Specific tools such as village resource maps, problem trend lines and institutional profiles assist in the analysis of community issues. Other tools such as farming systems' diagrams, seasonal calendars, daily activity profiles and household resource maps can be combined with gender analysis to analyse the livelihood systems of different socio-economic groups. A third set of tools helps communities and different socio-economic/gender-based focus groups identify and prioritize their problems and resource needs and to develop group or community action plans. PRA is very similar to the French méthode accélérée de recherche participative (MARP), and the two terms are used interchangeably in this paper. |

The analysis of difference: a way of identifying stakeholder groups at the local level. Gender, age, wealth/ income, ethnic or religious affiliation, caste, occupation and education all are indicators of difference. One tool for analysis of difference is participatory socio-economic ranking, in which community representatives divide the households of an area into different categories, defined according to area-specific criteria. Thus, the community itself identifies the socio- economic differences that are important. This tool allows a planning team to form small homogeneous focus groups, representing the different socio-economic categories. When a focus group uses the tools of participatory planning separately, its own particular constraints, resources, needs and priorities are more likely to be appropriately analysed and represented. | |

To make agricultural planning more responsive to the priorities of men and women farmers from different socio-economic groups, projects need to foster participation among as wide a range of stakeholders as possible. The ideal would be to have the active involvement in planning of representatives from all groups with a stake in the policy, programme or project. Some of the projects at the workshop experimented with the analysis of difference, an important method for identifying and involving different stakeholders at the community level.

What is Gender Analysis?

The current policy environment advocates involving women, but does not necessarily promote an analysis of gender issues in all policy formulation processes or in programme planning and implementation. Gender analysis is a methodology to study the different roles and responsibilities of women and men, the differences between men's and women's access to and control over resources, and the consequent variations in constraints, needs and priorities. Incorporating gender analysis into the tools of participatory agricultural planning helps planners understand how to modify the structure of policies and programmes so that women are involved equally with men. Gender analysis can demonstrate why some projects and policies have negative consequences for women.

Gender analysis identifies established patterns of gender-based inequality in economic life. It can, therefore, be seen as threatening to more advantaged stakeholders in the agricultural planning process. In many cases, senior staff or planners have been found to be more resistant to gender analysis than farmers and government field staff. And in some cases, the use of gender analysis tools at the community level may even foster a level of conflict that is detrimental to women's interests. To avoid such negative outcomes, local women should decide whether specific gender analysis tools are best used in mixed sex settings or by women alone. Where gender relations are hierarchical (i.e. in the vast majority of cases), participatory methods such as PRA should always include a separate women's problem analysis and probably a women's community action plan as well.

Does agricultural planning recognize gender differences?

It is difficult to judge how responsive current agricultural planning is to gender and socio-economic differences. The mainstream agricultural planning literature seems to pay very little attention to gender issues. Two textbooks on agricultural planning and policies published in the early 1990s (Mollett, 1990; Ellis, 1992) have chapters on women, but only Ellis has integrated gender issues into each topic. A review of ten recent volumes in FAO's Training Materials for Agricultural Planning series found that some volumes treat gender issues explicitly while others include them under the broader category of socio- economics.

In contrast to the neglect of gender issues in the mainstream agricultural planning literature, there is a rapidly growing literature specifically focused on gender and agricultural planning which has arisen from the "women's movement". Since the 1970s' critiques of the negative effects of development projects on women (Palmer, 1979), and the pioneering text outlining the so called Harvard framework for gender analysis (Overholt et al., 1985), there has been an explosion of literature on gender issues in agriculture, much of it giving practical guidelines and tools for gender analysis and project planning.2 This is the literature from which the projects represented at the workshop took their inspiration, as well as many of their methods.

The very existence of this extensive literature raises the question: Why has it not had more of an impact on the mainstream agricultural planning literature? Much of the answer involves timing. The great bulk of the gender and planning literature was produced in the late 1980s and the 1990s.3 Another part of the answer may be the isolation of women's issues in technical and academic discourse, a fate that has been shared by gender. However, the rapidly growing literature on gender, agriculture and planning has had a significant impact in helping to build the policy environment in which many governments are now mandating planners to increase participation and to involve women.

What is responsive planning?

Given all of the previous discussion, gender- and difference-sensitive participatory planning can be defined as agricultural development planning that responds to the diverse priorities of different groups of farmers, where these differences are based on gender, age, ethnicity, race and other socio-economic factors. Planners are aware of the differences and of how best to respond to them because the different groups of men and women farmers have taken an active part in planning agricultural development activities.

Six of the ten projects analysed here aimed at making some level of agricultural planning responsive to the priorities of women and men farmers (Costa Rica, Ethiopia, India, Namibia, Nepal and Tunisia).4 The Honduras project also had important impacts on policy in its later phases. The remaining projects (Afghanistan, Pakistan and Senegal), although they did not focus on influencing planning, used participatory and gender-sensitive methods that contributed to the analysis of what works, how and why.

This section analyses the factors that affected project outcomes, both successes and problems. It starts with an outline of the projects' various policy environments and then uses the six analytical categories (entry point, tools and methods, capacity building, gender information, linkages, and institutionalization) that all case writers incorporated in their studies.

The goal of most projects was to increase the responsiveness of agricultural planning to the priorities of men and women farmers, focusing on those with few resources. In most cases this goal reflected national policy directives to increase farmers' participation and to make sure that women's interests were reflected in plans and policies. Thus the projects were attempting to facilitate the realization of a goal shared by national planners.

The approach chosen was to demonstrate the relevance and usefulness (to agricultural planning) of participatory, gender-sensitive and socio-economic difference-sensitive participatory methods. Some projects also tried to increase the potential for gender-responsive planning by working to strengthen women's groups. Most trained local staff in the methods and tools used.

The methods varied from project to project, but usually included gender analysis and PRA or MARP. Some projects formed socio-economically similar and gender-specific focus groups so that PRA tools could be used separately - not only by men and women, but by subsectors such as poor men and young women.

The tools associated with these methods were chosen from those already described in the literature, combined (gender analysis tools, for example, were incorporated into PRA tools) or adapted to reflect local situations and focus group differences. In some cases, new tools were invented, reflecting the fact that PRA and gender analysis tools are evolving rapidly. Examples of specific tools used are described below.

The policy and planning environments encountered by the projects varied considerably, from those that were highly favourable to the introduction of gender-sensitive methods for participatory planning (Costa Rica, Ethiopia and Namibia) to the extreme case of Afghanistan, where women's involvement in productive activities has been drastically curtailed. In the early phases of the Senegal and Honduras projects (the mid-1980s), there was relatively little interest in gender roles per se and little concern with supporting women's production or organization at the government level. This changed in the 1990s, when the policy environment became more favourable to women's issues and to the concept of people's participation. Gender analysis, however, is still not acceptable in certain policy environments, e.g. Pakistan. In some countries, information about gender roles, constraints and priorities is still very scarce. Furthermore, in many cases, planners and decision-makers do not necessarily think that participatory planning requires the participation of both men and women farmers, much less representatives from resource-limited and minority population groups. This means that projects advocating gender-sensitive participatory methods must demonstrate their relevance and applicability to planning.

In Namibia, the Improving Information on Women's Contribution to Agricultural Production for Gender-Sensitive Planning project (1995 to 1997) focused on influencing the responsiveness of national agricultural planning. The project's hypothesis was that information gathered using participatory research could make the gender and socio-economic relationships on which farming systems are based more visible to planners. The project collaborated closely with another FAO project that was training agricultural extension staff in participatory extension training techniques in an effort to foster a client-responsive extension approach. "Clients" was understood to include women farmers, women heads of household and rural youth. Trained extension workers conducted PRA in four agro-ecological zones. University researchers incorporated the PRA-generated information into region-specific case studies, and regional and national workshops brought it to the attention of agricultural planners.

The policy and planning context in Namibia was highly favourable; there was a good fit between the gender-sensitive, participatory orientation of the National Agricultural Policy, which was passed in the project's first year, and project efforts to train agricultural officers in gender-sensitive, participatory methods. The National Agricultural Policy facilitated the project's efforts to interest planners and senior agricultural staff in gender-sensitive participatory tools for agricultural planning.

The Nepal project (1996 to 1997) focused on increasing the gender-responsiveness of district-level planning. Although FAO was assisting the government in formulating district agricultural plans during the project's implementation period, it was not associated with that effort. The project was located in the Women Farmers' Development Division of the Ministry of Agriculture (MOA). Project staff trained district officers from a wide variety of agencies (agriculture, livestock, extension, irrigation, cooperatives and the agricultural development bank) in PRA and gender analysis. Trainees then conducted PRA in seven villages in Nepal's three agro-ecological zones. District workshops had been planned to bring farmers together with district planners to discuss the community action plans resulting from the PRA, but they were cancelled under the pressure of time. Top-level planners who attended a project-sponsored national workshop suggested that, although there is a will to make planning gender- and needs-responsive, planners do not yet know how to change agricultural planning procedures. The project only had time to show how information could be generated, not how planning might be changed in response to that information.

Ethiopia's Improving Client-Oriented Extension Training project (1995 to 1996) aimed at promoting gender-responsive extension planning. The country's decentralization policy encouraged local-level planning, and created a helpful environment for the project. The project was designed in a participatory manner by the national project coordinator, six national extension experts and an international extension education adviser. It began by training trainers in PRA and gender analysis methods using a local-language training guide and video based on information gathered through PRA conducted by staff. The trainees then trained field staff in three regions (24 women and 58 men), who in turn carried out PRA in 15 villages. This was followed by a second training of trainers (TOT) to improve the PRA and gender analysis training materials. Previous reforms of the extension system had not succeeded in incorporating gender issues, so the project decided to provide additional extension programme training. Extension officers and field agents were assisted in analysing the implications of the information generated by PRA and using it to plan specific extension programmes for the villages concerned. The project made many efforts to involve planners, line agency managers and local officials in project activities. These efforts included an inception workshop, regional and zonal awareness-raising workshops and invitations to attend PRA training sessions and community meetings.

The India Development of Small-scale Livestock Activities project (Sikkim, 1995 to 1996) also combined gender analysis and PRA, and added the rapid appraisal of tenure and participatory monitoring. When the project was initiated, Sikkim, one of India's most isolated Himalayan states, had a policy environment in which agricultural policies and programmes paid no attention to gender roles and responsibilities. No information was available in the Animal Husbandry and Veterinary Services Department about gender- or age-specific roles in farming or livestock-rearing systems. The project trained a small group of mid-level field staff as trainers, using practical, field-based tools for looking at differences in access to livestock production resources according to gender and age. The new trainers trained local field staff, and together they conducted PRA aimed at understanding farmers' constraints, priorities and training needs for goat and chicken husbandry. Planners in the Forestry and the Rural Development Departments, as well as in the Animal Husbandry and Veterinary Services Department, all became interested in the effectiveness of participatory methods for generating gender information that is relevant to line agency programming and regional planning.

In Tunisia the on-going Policy and Strategy in Favour of Rural Women project (1996 to 1997) was mandated by government to assist in integrating rural women's issues in the Ninth Five-Year Plan. In the early 1990s, the government decentralized decision-making and management to the regional level and encouraged local experimentation with participatory rural development planning. Government's request for a project focused on rural women reflected its growing interest in gender-sensitive participatory approaches to agricultural planning. The project developed a methodology based on participatory surveys, using MARP tools to generate information on women's activities in three subsectors: agroforestry (the subject of the case study); irrigated agriculture; and fisheries. The tools focused primarily on women rather than on gender differences. Participatory analysis of the data was conducted with men as well as women. In the future, the project plans to formulate credit, training, technological support and group organization programmes in the subsectors where women are most active.

The Government of Costa Rica explicitly requested the Support for Women in Rural Areas in a Gender-Focused Framework project (1996 to 1997) to analyse gender issues in order to reduce the gender inequalities ex- perienced by rural women. The agricultural sector was undergoing a series of reforms aimed at increasing its competitiveness in the global economy. Policies were initiated to develop participatory extension methods, encourage negotiation with farmers and strengthen rural credit, all with the aim of increasing economic efficiency. Government wanted a high level of participation, calling for "the active participation of male and female producers and their organizations in the definition of policies, and in the identification, implementation, monitoring and control of activities". The project, implemented in the Atlantic region, focused on three major areas of concern: training of technical staff, planners and extensionists to create the national capacity and ability to transform the government's concern with gender into effective policies; strengthening of both rural women's organizations and public institutions to increase the demand for gender-sensitive policies and the capacity to develop them; and working at the policy level to identify problems related to the differences in impact that policies and programmes have on men and women and to dev-elop policies that overcome gender-based inequalities.

The Honduras case study covers a series of related "women's projects" (1983 to 1997) aimed at increasing the recognition of rural women as agricultural producers and strengthening producer groups in the agrarian reform sector. The projects worked with the National Agrarian Institute, which is the land reform and land registration agency, and with the Secretariat of Natural Resources, the government's main vehicle for extension and other agricultural services. In the 1980s there was little or no institutional recognition of women's productive roles in the rural sector, especially in agriculture. The projects thus began with a focus on income-generating activities, gradually expanding to include literacy and management training. By the 1990s, women's need for land and other productive resources was beginning to gain institutional recognition. Ironically, this change coincided with the advent of structural adjustment which stripped the National Agrarian Institute of its powers to reallocate land and severely reduced the capacity of the Secretariat of Natural Resources to provide technical services such as extension. The project reacted by developing the training of rural women volunteers as paratechnicians (promotoras campesinas) capable of helping women plan their own projects, including the organization and management of savings and credit groups. This methodology was gradually institutionalized. The long-term capacity building effort has been directly responsible for the increasing involvement of women in farmers' organizations and of women's NGOs in the planning process.

In Afghanistan, the Animal Health and Livestock Production Programme (1994 to 1997) began to confront gender issues when FAO amalgamated it (in 1995) with a new project called Promotion of Farmers' Participation through the Implementation of Animal Health and Production Improvement Modules (PIHAM). PIHAM introduced participatory methods that revealed women's extensive knowledge and role in livestock and poultry rearing and convinced the veterinary staff from the animal health project that, without including both women's and men's knowledge about animals, project interventions were unlikely to be effective. PIHAM trained female veterinary staff in participatory methods for livestock extension. They, in turn, modified the training material to make it more practical for women. The context in which this work was carried out was, however, extremely unfavourable. The long period of civil war had wiped out nearly all vestiges of government services in rural areas. As the Taliban forces took over, women's rights to engage in almost any productive activities outside the home were increasingly denied. The project faced tremendous obstacles in training female staff, but the women veterinarians persevered to involve village women in participatory training and livestock monitoring.

From its outset in 1986, Senegal's Northwest Groundnut Basin Village Reforestation (PREVINOBA) project opted for a strategy of popular involvement to deal with deforestation and erosion in the groundnut basin. But participatory dialogue and exchange soon highlighted the fact that people's concerns went beyond the simple framework of rural forestry. As a result, the second phase of PREVINOBA had the broader mandate of drawing up local land development and management plans that reconcile people's interests with policy orientations in the sector, restore and conserve the environment and improve production, all within the framework of sustainable development. The current phase (1995 to 1999) emphasizes consolidation of the lessons learned for expansion. It aims at establishing control by farmers' organizations and NGOs, in addition to government structures. PREVINOBA did not set out to focus on women's participation, but the context in which it operated forced gender issues to be taken into account. The absence of rural men for the greater part of the year meant that women became indispensable in the design and set-up of land management plans. The project also responded to the needs identified by women, including improved ovens, millet mills, oil presses and access to credit and to literacy classes.

In Pakistan, the Inter-Regional Project for Participatory Upland Conservation (1993 to 1997) had separate men's and women's programmes to comply with cultural norms. The women's programme encountered significant resistance from senior management in the Forest and Wildlife Department over the incorporation of gender analysis into its participatory methods. In the end, the programme was obliged to restrict its use of PRA tools to the assessment of women's problems and priorities. In spite of the severe ecological problems, conservation was a low priority for women, so the project made the organization of women's associations the final step in each PRA exercise. It provided training in income-generating activities and helped women to organize village savings and credit organizations. The project's concern with natural resource management was developed through a series of slide shows to stimulate discussion. Although the women eventually developed the discussion topics and slide shows themselves, it is unlikely that they will have a significant impact on the area's serious environmental problems, primarily because the owners of lucrative orchards are engaging in heavy-duty pump irrigation, an activity that has already severely lowered the water table and threatens, if continued, to force the population to abandon the area altogether.

Planning takes place at many levels:

The projects being reviewed had to decide what their entry points were, in other words, where and how they could enter the planning system.

The entry points for five of the projects (Afghanistan, Ethiopia, India, Namibia and Nepal) were very similar - the training of field-level extension agents in PRA and gender analysis so that they could gather information that is useful for gender-responsive planning. The levels of planning for which gender-specific information was gathered varied from the national (Namibia and Tunisia), to the district or regional (Costa Rica and Nepal), the subsectoral (Ethiopia, Honduras and India) or the project itself (Afghanistan, Pakistan and Senegal). The Tunisia project was the only one that began with an explicit attempt to involve a planning agency in defining its needs. The Costa Rica project began with a detailed study of planning processes. The highly successful Ethiopia project began with participatory planning of the project itself.

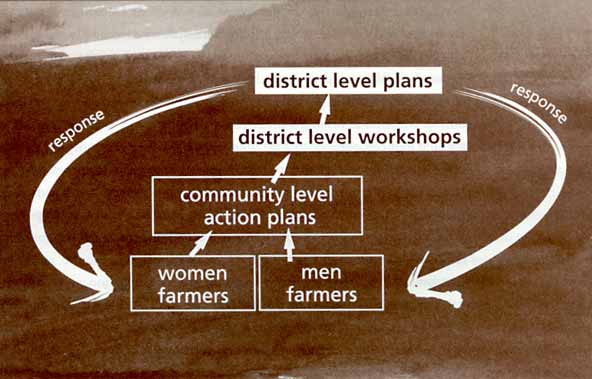

Gender sensitive planning model - Nepal |

|

This diagram illustrates how the project in Nepal attempted to facilitate a process of participatory, gender responsive planning at the district level. The project started by training a wide range of district officers and field staff in PRA and gender analysis. PRA was conducted with separate groups of men and women farmers, with the aim of providing gender-specific information and developing community action plans as potential inputs for district planning. The project's use of separate men's and women's focus groups was an attempt to assure that women's needs and priorities would be represented equally with men's. However, when men and women farmers were brought together to produce a single community action plan, in most cases women's priorities were overshadowed by men's. The project had planned to organize district-level workshops where farmers would discuss their community action plans with district planners. This would have provided a direct link to district planning and, if implemented, would have evolved into a best practice. Nepal was one of the few projects that attempted to forge such a direct a link with planning processes. (But, as mentioned earlier, the district workshops were cancelled.)

Ethiopia's client-oriented extension training project began with a participatory approach to the planning of its own activities. The project was jointly designed by the national project coordinator, six national extension experts and an international extension education adviser. Project staff then prepared materials for a TOT programme by conducting preliminary PRA in three regions to provide local examples for an Amharic-language training guide entitled How to make your extension programme client-oriented. The primary entry points were field-level extension agents and farmers.

The entry point for Tunisia's Technical Cooperation Programme, Policy and Strategy in Favour of Rural Women, was the project's request to the Department of Planning to define its needs for data on women. The project then trained the field workers who made up the research team, conducted a statistical survey to provide data on rural women's productive activities and engaged in participatory research using PRA to elicit information about women's and men's separate priorities in the area of economic activities for women. The Tunisia project seems to be the only one that began by consulting the national planning agency on its needs.

The Costa Rica project, which was explicitly mandated to use gender analysis in order to understand and correct women farmers' under-representation in agricultural services, promoted an extensive and participatory process for the detailed review of all aspects of agricultural policy. Planners, agricultural specialists, NGOs and representatives of rural organizations participated in the development of this process. One of the main characteristics of the Costa Rica project was that it took action, simultaneously, at three levels: the community level, working with grassroots' organizations and rural workers; the regional level, in connection with decentralized agencies from the agricultural sector and local government; and the national level, with planners, national NGOs and representatives from the major farmers' organizations. As stressed in the case study's analysis of the project's entry point, these activities took place simultaneously because each was seen to have critical feedback for the others. This project is one of the few that conducted a detailed study of planning before it entered the planning system.

Namibia's Improving Information on Women's Contribution to Agricultural Production for Gender-Sensitive Planning project was executed in close collaboration with a second project focused on training extension workers in PRA and gender analysis. This provided the project with an obvious entry point, i.e. the extension agents trained in PRA and gender analysis could be used to collect gender-specific information on the farming systems in the country's four major agro-ecological zones. The PRA was expected to produce gender, socio-economic and location-specific information that could be used by national agricultural planners who had recently been mandated to integrate women farmers into all policies and programmes.

India's Sikkim Livestock project began by training agricultural and community development officers as trainers. The areas covered included analytical problem-solving and pedagogical skills as well as interdisciplinary work, participatory methods and gender analysis. The newly trained trainers conducted PRA and gender analysis training for field staff who, in turn, carried out PRA in a series of villages to produce information that could be used in the planning of livestock services. TOT as an entry point improved the likelihood of activities being sustained after a project comes to an end.

In Honduras, when the project started in 1983 there were no institutional mechanisms for working with rural women as productive agents. This prompted the project to work directly with rural women, organizing small groups to encourage income-generating projects for crop and animal production and providing credit for their implementation.

Senegal's reforestation project's entry point was to work directly with villagers. In most cases however, village authority was exercised by male village and religious chiefs. Women were traditionally absent, although the eldest were consulted before final decisions were made. With the backing of village authorities, PREVINOBA was able to build partnerships with village organizations, including women's advancement groups. Given men's absence for most of the year, women were organized into collectives for the majority of reforestation and cultivation activities, including orchard management. For a few activities, such as the installation of windbreaks, both men and women were involved.

In Pakistan, the staff of the women's programme of the natural resource management project conducted PRA exercises with village women as its entry point for each of the areas in which it worked. Since the PRA demonstrated that women had little interest in environmental conservation activities, the exercises culminated in the formation of women's associations which planned their own activities, largely income-generating projects.

The entry point of Afghanistan's PIHAM project was the training of veterinarians from the staff of the existing Animal Health and Livestock Production Programme in gender-sensitive PRA and project monitoring. The participatory work with farmers that followed this training had a major impact on improving veterinarians' attitudes towards farmers.

Most of the projects at the workshop used some form of PRA and/or gender analysis. Projects that used PRA combined with gender analysis and the analysis of difference were particularly successful in demonstrating their relevance and practicality for gender-responsive participatory planning.

PRA, when combined with gender analysis and the analysis of difference, is both powerful and relatively cost-effective5 because it serves three functions simultaneously.

1) It is an efficient method of collecting the information on gender and other differences among farmers that is needed for gender-responsive planning.

2) The method is easy to learn and helps field workers to understand rapidly the gender, socio-economic and technical issues in local farming systems.

3) It is an effective means of involving different groups of farmers in problem analysis and planning.

Some of the most important PRA and gender analysis tools used in the projects are described in the table on page 32 that was taken from the Nepal case study. The information gathered using these tools was illustrated on large posters and analysed by different focus groups or by the community as a whole. Both focus groups and communities prioritized problems (using, for example, pair-wise ranking) and analysed the feasibility of potential solutions. PRA exercises often concluded with the development of a community action plan or with separate action plans that reflected the specific priorities of different focus groups. The table on page 33 which was taken from the Namibia case study shows a framework for gender analysis and PRA.

The action plans and other information generated by PRA tools can be used as inputs for bottom-up planning. When compiled and analysed at district or higher levels, focus group priorities and action plans provide information that can make programme, area and policy planning more responsive to gender and socio-economic differences.

Gender analysis and PRA tools | |

|

Example from Nepal (Sontheimer et al, 1997) |

|

TOOL |

PURPOSE(S) |

Social and resource mapping |

Indicate spatial distribution of roads,

forests, water resources, institutions |

Seasonal calendar |

Assess

workload of women and men by season |

Economic well-being ranking |

Understand local people's criteria of wealth |

Daily activity schedule |

Identify daily patterns of activity based on gender division of labour on an hourly basis and understand how busy women and men are in a day, how long they work and when they have spare time for social and development activities |

Resources analyses |

Indicate access to and control over private, community and public resources by gender |

Mobility mapping |

Understand

gender equalities/inequalities in terms of men's and women's contact with the outside

world |

Decision-making

matrix |

Understand

decision-making on farming practice issues by gender |

Pair-wise

ranking |

Identify and

prioritize the problems experienced by men and women |

It is important to remember, however, that participatory tools will not automatically reflect gender or other differences among community groups when they are used in community-wide meetings. PRA tools, in fact, have often been used in a manner that is insensitive to critical differences within communities, including gender. It is thus essential to combine PRA, gender analysis and the analysis of difference in order to understand socio-economic and gender-based difference.

The gender analysis and PRA framework |

||

Example from Namibia (Sonttheimer et al, 1997) | ||

STAGE IN GENDER ANALYSIS |

ANSWERS THE QUESTION(S) |

RELATED PRA TOOLS |

CONTEXT |

What is getting better? |

Village maps |

ACTIVITIES |

Who does what? |

Daily activity profiles |

RESOURCES |

Who has what? |

Gender resource mapping |

WORK PLAN FOR SUCCESS |

What should be done? |

Identifying problems |

Project experiences with participatory methods, such as PRA and MARP, demonstrate the potential of participatory tools to generate information that is relevant to planning in a variety of agricultural subsectors. They also demonstrate the importance of using participatory methods in conjunction with gender analysis and the analysis of difference in order to incorporate less powerful people into the participatory process.

Among the PRA tools used, several projects found seasonal calendars and daily activity profiles to be the most useful for demonstrating the significant contribution of women's labour and knowledge to agricultural production processes. Problem- and opportunity-ranking when used separately by men and women revealed important gender differences in constraints and priorities.

The Nepal project found that women's voices tended to be lost when men's and women's separate analyses were brought together to develop a community action plan, suggesting that, when action plans are used, they should be developed separately by all focus groups, thereby allowing the priorities of non-dominant groups to be communicated to planners. Several projects remarked that, since PRA requires a great deal of community involvement and effort, it is important to plan for follow-up support, such as the opportunity to discuss action plans with planners or to have a project or service (such as extension) actually assist in meeting the priority needs identified by the PRA.

The Ethiopia and Namibia projects demonstrated the importance of training extension officers and agents in how to use PRA and gender analysis-generated information to plan extension programmes that are customized to meet the needs and priorities of different client groups. The issue of exactly how planners can respond to farmer-generated information needs to be addressed more directly. These and other methods are discussed in the following paragraphs.

Focus groups. In Ethiopia, India, Namibia and Nepal the use of focus groups made up of people from similar socio-economic levels gave disadvantaged sectors of the community a voice in the PRA process and facilitated the identification and analysis of the specific constraints and priorities of young men and women, the elderly, the poor, etc.

Use of local cases for PRA training. The projects that based their PRA and gender analysis training on local cases were able to be especially sensitive to the types of gender, socio-economic, ethnic and age differences that are relevant to gender- and difference-responsive agricultural planning in areas in which the training was taking place. These projects had particularly successful training programmes, in part because the tools were obviously relevant to the analysis of local situations.

Interdisciplinary PRA facilitation teams. The India project developed an important method of using newly trained facilitators to carry out PRA. Interdisciplinary two-person PRA implementation teams were formed with staff from different government departments. Whenever possible, the teams were made up of a male and a female member. Teams were rotated every day so that technical officers and field agents would be exposed to a variety of professional skills and gender attitudes. The team leader floated among the teams working in each village. This approach was successful in convincing sceptical team members of the value of gender analysis. It also gave farmers access to staff from several government departments.

Adaptation of PRA and gender analysis tools to local circumstances. Those carrying out PRA in Nepal found that they needed to make very special efforts in order to ensure that women speak in PRA sessions, even when PRA is conducted in separate groups of men and women. When mixed sessions are held, facilitators must be able to handle male dominance in discussions. In Ethiopia, it was essential that work was carried out in single-sex groups when learning about labour activities and gender differences in access to and control over resources, because cultural barriers prevent women from speaking out on sensitive issues in the presence of men. In Afghanistan, the situation of civil strife and the Taliban-imposed restrictions on women required the modification of many PRA tools. The project, nonetheless, used a wide variety of means to get people involved. In Pakistan, project management's resistance to gender analysis and to using the information generated by PRA to modify project implementation prompted the women's programme to use PRA to establish partnership with women's groups rather than as a tool for obtaining information relevant to future project planning.

Statistical surveys as supplements to PRA-generated information. The Namibia project found that the information generated by PRA and gender analysis alone could not provide adequate data on the frequency of gender and other group differences. Hence researchers from the university, who were familiar with PRA and other participatory methods, were engaged to supplement the PRA-generated information with survey data and information from secondary sources. The Tunisia project also combined participatory-generated data with more standard surveys to help the government define a strategy and plan of action for integrating women into the Ninth Five-Year Plan.

Participatory impact monitoring. The India project used a method of participatory impact monitoring in which staff and consultants made frequent informal visits to project participants. These visits concentrated on the emerging issues that village women and men viewed as significant, with a special focus on who was benefiting and how. Participatory monitoring identified both positive and negative outcomes, many of which were unexpected.

Strengthening of grassroots organizations. The Costa Rica, Honduras, Pakistan and Senegal projects stressed the importance of strengthening grassroots organizations, especially women's groups, so that they could make better use of existing government services and improve their negotiating skills for demanding better services. The Honduras project worked to strengthen women's groups, first by training women volunteers as agricultural extension "linkage agents" and then by training volunteers as "paratechnicians" capable of supporting women's micro-enterprises and local savings and credit associations. The Costa Rica project taught organizational management and project formulation and management skills. Its workshops for grassroots women's organizations identified common gender problems in each local area, and helped to create a regional rural women's association that could analyse regional problems and bring them to the attention of planners. The Nepal case study suggests that, when PRA tools are used, farmers learn valuable skills such as problem analysis and priority ranking which they can use when lobbying for support from government and other agencies.

Involvement of senior staff and decision-makers in gender-responsive participatory planning activities. India's Sikkim livestock project had little difficulty in forging supportive relations with the newer generation of managers appointed in the Animal Health and Veterinary Science Department during the latter period of the project. Initially, however, many staff of the Animal Health and Veterinary Science Department were reluctant to accept such unconventional approaches as PRA and gender analysis. Some, including the national project director, never fully accepted the project's methods, but the majority gradually came to recognize the relevance of gender-responsive approaches for livestock programme planning. The project accomplished this by constantly raising the problem of appropriate targeting, insisting on asking who does what and how should that affect who gets extension services. Interdepartmental workshops facilitated dialogue among Forest Department, Rural Development Department and Animal Health and Veterinary Science Department staff, enabling people who were interested in gender-sensitive participatory methods to encourage their more reluctant colleagues to try them.

The Ethiopia project also used a wide variety of methods to involve senior staff in project activities: inception workshops in each project area; invitations to open or closed training sessions; invitations to attend PRA sessions; and workshops to discuss the results of PRA activities. The Namibia project conducted a special workshop for planners on the analysis of difference and the implications of PRA results for policy-planning. The Costa Rica project to a large extent used FAO's Socio-economic and Gender Analysis (SEAGA) approach, considering three interrelated levels of analysis/work - the macrolevel, the intermediate level (both subsectoral and institutional) and the local level (including regional) - using participatory methods and tools. The project mainly used a workshop format and interdisciplinary working groups to involve various levels of government personnel in gender analysis and to promote gender analysis of existing agricultural policies among planners. The methodology developed by the Honduras projects facilitated the use of gender analysis at all levels, with the aim of permeating public and private agencies with an understanding of women's productive roles.

Establishing a mechanism that responds to community planning efforts. The Ethiopia, Nepal and Tunisia case studies all emphasized that successful PRA and MARP depends on adequate response and follow-up mechanisms. Farmers engaging in full PRA, which includes the development of a community or group action plan, are anxious to have institutional support for their plans. This is a critical issue for projects of this sort. It may also be a reason for planners' hesitation to use PRA or other methods that encourage full-scale bottom-up planning.

Direct training in client-responsive agricultural programming. The client-oriented extension training project in Ethiopia found that, after training extension agents in the use of PRA and gender analysis to generate information for planning, field agents and officers were still not sure how to use the information in planning their own programmes and work plans. It was, therefore, important to develop training modules that dealt directly with how to incorporate information into extension programming. This experience suggests that projects to promote gender- and difference-responsive agricultural planning should consider adding specific training modules to help planners to apply the information generated by PRA and gender analysis into actual planning processes.

Capacities built at each level after project introduction | |

ACTOR |

CAPACITIES BUILT |

Village women |

Women farmers exchanged experiences; learned about the responsibilities of keeping livestock, e.g. mating time; increased ability to record/monitor changes (reporting forms); learned how to record disease patterns and vaccination times (seasonal calendars); learned importance of talking to experienced women; realized that their role in livestock management was greater than they thought (labour analysis); learned how to identify many causes of problems; found solutions based on resources at hand; developed easier, cheaper, more effective practices (input/output charts). |

Village men |

Learned how much women are involved in livestock (labour analysis, seasonal calendars, etc.) and the importance of discussing problems, finding diagnoses, etc. with them; improved relationships between villagers and staff; gained many of the same capacities as women (see above). |

Male and female |

Attitude and behaviour towards farmers

changed ( "no longer proud"); |

Veterinary field units |

Improved overall capacity to understand importance of participatory approaches; learned from initiators through staff discussions, sharing. |

Project management staff |

Gained participatory training skills for key project management (participation in initial training modules); used participatory methods for monitoring and project design (transfer of skills from training, e.g. women's programme revisions); learned from mistakes and how to correct same; improved overall planning capacity (through better understanding of community needs, direct contact and continuous monitoring of project pilot and replication phases); recognized that, without the involvement of women, key livestock information is incomplete (through participating in early project training and analysis). |

NGOs |

Became more aware of the farming systems in their area and elsewhere (through exchange related to project processes); learned how to modify training (manuals). |

UN agencies in Afghanistan |

Raised their awareness of the importance of community participation in planning (through sharing of project experiences with other UN agencies); developed potential for sharing of methods with other projects/programmes in the future. |

In the great majority of cases, capacity building consisted primarily of training of government line agency officers and field workers in participatory methods and/or gender analysis. Projects using PRA and gender analysis methods conducted short introductory training sessions and subsequently trained field officers "on the job" during actual PRA and gender analysis village exercises lasting from five to ten days each. Project staff conducted the initial training. In the three cases where a TOT approach was used (Ethiopia, India and Namibia), project staff trained the trainers who then trained other local-area staff. The table on the following page summarizes the sort of effects that projects had on capacity building.

Successful PRA was conducted by field staff who had received only three to five days of preliminary training in PRA and gender analysis tools, because becoming competent in the use of participatory approaches is more dependent on practice than on detailed theoretical training. On the other hand, it was found that further training after conducting a PRA is important to consolidate and develop further participatory planning skills.

Opportunities for trainees to analyse the results of the PRA and to adapt their tools and methods to reflect local realities better were important components of training in some projects (Afghanistan, Ethiopia and Namibia). Several projects emphasized the importance of spreading formal training sessions and workshops over time so that intervening experiences could be analysed and integrated into planning processes. The Ethiopia project found that training in specific extension planning procedures was needed so that field staff could apply what they had learned from conducting PRA to their own work.

Some projects (Costa Rica, Honduras, Pakistan and Senegal) directly trained women farmers in group organization as well as technical skills. Pakistan also taught PRA, Senegal taught MARP and Honduras and Costa Rica taught gender analysis at this level (as did the other projects using these methods). Some projects (Costa Rica, Ethiopia and Namibia) provided informal and formal training at planning and line agency management levels.

In Namibia formal TOT was conducted in three separate sessions spread over the course of the project. The first TOT focused on the analysis of difference and PRA training, after which trainees conducted PRA. The implementation of PRA and gender analysis exercises helped trainees to gain a clearer understanding of such concepts as gender roles, farming systems and client-responsive extension approaches. During the second TOT, the initial PRA findings were reviewed, case studies were prepared for the training of other extension agents and trainees were taught basic principles of adult education. The third, initially unforeseen, TOT session was on preparing trainees to conduct regional-level workshops in which the PRA results were to be shared with planners. The use of multiple training sessions interspersed with practical application of PRA was key to the success of the project's capacity building efforts.

The Ethiopia project also used a TOT approach. Before conducting the first TOT, project staff prepared materials based on local situations, wrote an Amharic-language guidebook on how to make the extension programme client-oriented, and produced a video based on pilot PRA exercises. The first two-week TOT covered extension, adult education, gender analysis and PRA. The new trainers then trained local subject-matter specialists and field agents from each project zone. PRA lasting from eight to ten days was conducted in five villages. A second three-week TOT session reviewed the experience of implementing PRA, improved the training materials and discussed ways of using PRA-generated information in planning extension programmes. At this point, it was decided that the trainers should also train district-level extension agents in how to use PRA information to develop their individual work programmes. Although the direct training of field agents in practical extension planning had not been foreseen in the original project plan, the case study suggests that it was, in fact, an essential step in assisting planners and field agents to use PRA information to make their own planning processes responsive to gender and other differences among farmers.

The Ethiopia case study mentions the fact that the project's use of participatory methods in its own internal planning processes proved to be a major factor in the success of its capacity building programme. The training objectives, content, location and length were all planned jointly by the zonal and regional coordinators, the international extension adviser and the national project coordinator.