|

A FRAMEWORK FOR GENDER-RESPONSIVE AGRICULTURAL DEVELOPMENT

PLANNING |

BEST PRACTICES FROM BUSINESS and best practices from participatory development: this may seem a strange pair but as I have been reading through books on "the management revolution" and through case studies on gender and participation, I have been astounded by the parallels. For example, the top concern of the chief executives of the world's most successful businesses is "creating total client responsiveness". This sounds strikingly similar to what we are trying to achieve with participatory and gender-responsive planning.

The guiding principles and objectives outlined in this document are one of the outcomes of the FAO Global Workshop, From Farmer to Planner and Back: Harvesting Best Practices. The women and men who participated, all of whom have hands-on experience with the implementation of participatory gender-responsive development work in Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Near East, made it clear where the constraints continue to lie. I learned that the greatest barrier to mainstreaming gender and participation in agricultural development stems not from the field, but from the very institutions we work with.

The Responsive Planner, I have taken the workshop participants' lessons and linked them with the lessons learned in the private sector. This may sound a little farfetched, but many of today's struggles in participatory development have already been overcome in the private sector. Granted, businesses are driven by different motives; they struggle to profit from volatile market forces. But they have found new and successful ways of working towards objectives that we also seek in the world of agricultural development, such as effectiveness, efficiency, adaptability and responsiveness to diversity and change. These new ways of working include strategic planning, participation, decentralization and demand-driven services. Sound familiar?

THERE IS AN UNMET CHALLENGE IN THE WORLD of agricultural development. That challenge is to mainstream participation and gender issues. Meeting this challenge requires changes in the procedures and operations of the large agricultural development institutions, and in the responsibilities of the planners who work within them.

Agricultural development that is explicitly participatory and gender-responsive is often found only in short-term, small-scale pilot projects or in small budget sub-programmes of larger projects. Limited support, naturally, translates into limited impact. Meanwhile, the bulk of large-scale and long-term agricultural development programmes, managed by the large national and international institutions, continue as before, with little or no attention to the microlevel complexities raised by gender and participation.

Institutional Responsiveness |

Institutional responsiveness refers to the variety of ways in which large-scale agriculture institutions in government or civil society can respond - with services, training, inputs, technical advice - to the needs, priorities and requests of smaller-scale organizations and communities of women and men. It is about flexibility. Responding to the priorities of local farmers entails creating or strengthening institutional mechanisms for learning and responding to diversity and change. |

INSTITUTIONAL RESPONSIVENESS IS NOT A STATIC COMMODITY. |

Good institutional responsiveness in one place may be quite different from that in another place. An understanding of responsiveness may evolve over time, due to changes in the social/political environment, changes in the physical/economic environment, changes in farmers' needs and aspirations, or changes in the institutions' experience or mandate. The overall objective of creating institutional responsiveness is effective agricultural development based on rural people's real needs. |

The responsibility of large agricultural development bureaucracies in participation is to respond to the needs of women and men farmers - each in their own right - by providing the best services possible. The use of participatory methods to enable farmers to plan their own development activities is necessary but insufficient. There must be follow-up.

The staff members of FAO Headquarters in Rome learned a lot about these issues from the planners and project staff from Africa, Asia, LatinAmerica and the Near East, who participated in the FAO Global Workshop, From Farmer to Planner and Back: Harvesting Best Practices. These participants, brought a number of important lessons to FAO. First, they shared a wide variety of ways of making participatory planning and monitoring methods more explicitly gender-responsive. Second, they confirmed that the livelihood strategies and priorities of women usually differ from those of men, as well as from what development professionals often assume. Third, they demonstrated new processes for linking gender-disaggregated field information to policy-makers. Many policy-makers are now well aware of the gender/participation jargon and most agricultural development policies at least mention the importance of women and community participation.

PRA has evolved so fast, and continues to evolve so differently, that no final description can serve. At one stage PRA was called "an approach and methods for learning about rural life and conditions from, with and by rural people", with the emphasis on learning by outsiders. The prepositions were then reversed to read `by, with and from', as the analysis and learning shifted from `us' to `them'. Then the term PRA came to cover more than just learning. It extended into analysis, planning, action, monitoring and evaluation. It was also used to describe a variety of approaches as they evolved in different countries, contexts and organizations. To cover these, it was described in May 1994 as: `a family of approaches and methods to enable rural people to share, enhance, and analyse their knowledge of life and conditions, to plan and to act'... To this can now be added `and to monitor and evaluate'. For some, too, it is now a philosophy and a way of life which stresses self-critical awareness and commitment to the poor, weak and vulnerable.

- Chambers (1997:104)

FAO also learned that the "and Back" part is still very weak. Agriculture institutions still lack the mechanisms for responding to the voices of rural women and men. Without exception, the experience in all 12 countries participating in From Farmer to Planner and Back: Harvesting Best Practices, showed that the positive impacts of gender and participation are sustained only when institutional policies, procedures and norms support them.

All too often, the use of participatory approaches, such as Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA), is introduced during implementation of already de-signed programmes. The priorities revealed by the PRA may contradict those already fixed by the programme and the institution may be unable or unwilling to make the necessary changes. Both farmers and field staff, who are often the only people to receive training in participatory approaches, can becomedisillusioned.

The workshop participants all stressed that for these approaches to work, they must permeate the entire system. This means from the grassroots up - all the way up - and back again. Sufficient resources and time must be allocated and political commitment must be sincere if field-level staff and local women and men are to remain motivated to work through analysis and change. A major constraint to participatory gender-responsive agricultural development is the lack of institutionalization.

The institutionalization of gender and participation cannot occur on a large scale without the involvement of large-scale institutions, such as ministries of agriculture, large non-governmental organizations (NGOs), the FAO, donor agencies and others. But for large institutions to support increased and higher-quality participation in more places means more than focusing on local women and men. It also means changing the institutions themselves. Even though these large bureaucracies have an advantage of scale over local groups, the disadvantage is that their working procedures are usually neither participatory nor gender-responsive.

Institutionalization |

Institutionalization is about mainstreaming and long-term commitment. When something is institutionalized it is part of an on-going process - it is not a special or one-time-only event. Institutionalization of participatory gender-responsive agricultural development (PGRAD) planning means that participation and gender issues are merged with, or transform, the vision, mandate, priorities and procedures of the institutions responsible for agricultural development. The overall objective of institutionalization is sustainability. |

Yet, more and more, the large bureaucracies of agricultural development have a growing interest in gender and participation. This interest has grown, in part, because knowledge of local conditions and local priorities has proven to be essential to improving food security and natural resources management and, in part, due to pressure from progressive donors and NGOs. But, the internal systems, structures and procedures of development institutions are not as conducive as they could be. Work tends to be organized around standardized, bureaucratic procedures, including fixed targets, tight deadlines and inflexible budgets, which inhibit more flexible, innovative practices. The challenge of integrating gender and participation cannot be met without dealing with this web of internal bureaucratic elements.

The From Farmer to Planner and Back workshop participants were explicit about where the weaknesses lie. They said that the focus on the field-level and policy-level has left out the middle: those who plan agricultural development programmes and oversee their implementation. Planners have been left out which has had negative consequences for participatory efforts as a whole. While many field staff (and some policy-makers) have learned new approaches and skills for gender analysis and participation, planners have continued with status quo planning procedures, many feeling threatened by the changes that they do not understand. In some cases, the participatory work of field staff has been curtailed by traditional planning processes and supervision criteria. But the planners have little room for manoeuvring unless the institutions they work in change too.

The workshop participants were asked to tackle this challenge explicitly and worked to draft their recommendations for a participatory and gender-responsive planning framework. Their recommendations, which form the backbone of this document, emphasized the need to:

Framework: |

|

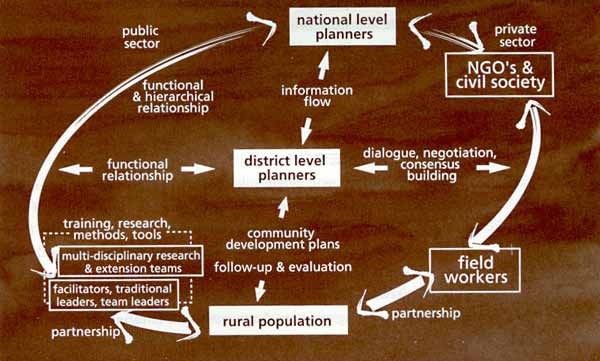

The institutional challenge then is not only determining how to make single institutions more participatory through internal organizational change, but also developing more collaboration and linkages between and among institutions which may not have worked together in the past. Participatory development on a large scale requires learning to build cross-sector partnerships at all levels, between local and external organizations, as well as among civil society, governmental and private institutions. When and how to develop such partnerships or coalitions are critical strategic questions. New ways of planning and management are needed which can operate across institutional and power differences, while keeping the participation of the grassroots women and men at the centre of the process.

Identifying key principles to guide the process of institutional change is a useful starting point. The Responsive Planner proposes such principles, with its hypothesis that for agricultural development institutions to become responsive, they must become "learning organizations". The challenge is to flatten and soften hierarchy, in order to develop a "rapid response task culture". In other words, to adopt and promote procedures, norms and rewards that embrace field-level realities of diversity and change, and encourage open-ended listening at all levels.

Functions also must be clarified before new processes can be designed. The Responsive Planner focuses on the responsibilities of one of the key players within agricultural development institutions - the planner. Without the dedicated support and participation of agricultural planners, in real terms rather than merely an adoption of the rhetoric, PGRAD will not succeed. Planners (who often hold management positions) are crucial.

The Responsive Planner offers both broad principles and specific planning steps. By dealing with agricultural development institutions as a whole - as well as with the roles of the planners within them - it is hoped that each of us will find several ideas that will help us respond better to rural people's needs.

Planners can play many different roles. Micro-level planners are often logical framework specialists. They strive to capture the complexities of agricultural development within simple cause-effect formulas, while also listing the factors that might derail them. The macro-level planners usually turn their skills to 5-year and 10-year national agricultural development plans, policy framework papers, poverty assessments, food security strategies and special papers setting out how the country will implement the resolutions of various international conferences. Planners also often act as facilitators of decision-making by policy-makers, as technical experts in sectoral areas, or both. Planners are also analysts of existing or potential strategies, or strategists themselves.

The traditional tasks of planners |

|

Benadavid-Val (FAO, 1991) | |

Promote a common language and conceptual base among planning participants | |

You do not have to have the title of "planner" to be a planner. Many women and men whose work contributes to the planning of agricultural development are policy-makers, project managers, technical officers, supervisors or even consultants.

The Responsive Planner is written especially for:

Agricultural development planning, as a profession and as a system, has developed many axioms over the past decades. But in the past 20 years, the conditions that led to the emergence of these universal truths have blown apart.

The work of agricultural development planning carries enormous responsibility, influencing the wellbeing of hundreds, thousands or even millions of women, men and children. It must be carried out with integrity. But, as agricultural development planners we need to confront a core learning dilemma. We know that we (like everybody) learn best from experience--but we do not experience the direct consequences of our decisions. It is not our own farms, our own livelihoods, or the household food security of our own families which are affected.

Agricultural development institutions are taking an increasingly active interest in gender issues and participatory approaches because of four main forces (Thompson, 1998).

1) Survival. The pressures of structural adjustment, rising debt, declining terms of trade, economic liberalization and market integration are forcing many government agencies to reduce the size of their civilservices and thus their capacities for direct service provision. In the drive for survival, governments are searching for new ways to do more with less. In some cases, the state is doing this by establishing new partnerships with local and international NGOs, many of whom strongly promote gender and participation issues.

2) Donor Pressure. The donor community has been instrumental in stimulating national and international agencies' growing interest in gender and participation. With increasing frequency, donors are placing conditions on grants and loans to governments, requiring them to support community participation and to ensure that women benefit.

3) Failure. During the past two decades, "blueprint" development strategies have been shown to be ineffective in meeting the basic needs of large numbers of marginalized, vulnerable people. The standardized, reductionist approaches to agricultural development have proven incapable of addressing the complex realities of poor people, which are locally specific, diverse and dynamic.

4) Success. The successful application of gender-responsive participatory approaches, especially by NGOs but also by public sector agencies, has attracted the attention of planners. These success stories have demonstrated that it is possible for large-scale agricultural development agencies to implement people-centred approaches and attain positive results.

Let's face it. Planning without attention to gender and participation is easier than planning with it. It requires attention to endless variations of micro-level details. It requires both high-level analytical skill and great humility. It forces us to recognize diversity and change. But it also leads us to more successful, more equitable and more sustainable agricultural development because we learn exactly what is needed in a particular place, by particular groups of people. Gender and participation permit us to plan on the basis of facts, rather than assumptions or generalizations. With participatory, gender-responsive planning, the planner's chief job is to dismantle dysfunctional old axioms and prepare people and institutions to deal with the realistic complexities of diversity and change.

What is PGRAD? |

Benadavid-Val (FAO, 1991) |

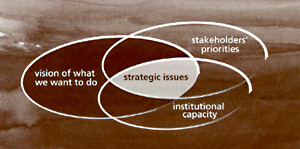

Participatory, gender-responsive agricultural development planning (PGRAD) responds to the differing priorities of different groups of farmers where those differences are based on gender, age, ethnicity, race, religion, wealth and other socio-economic factors. Planners are aware of these differences and of how best to respond to them because the women and men in the groups have taken an active part in planning the agricultural development activities. It is a process in which both farmers and planners commit to follow-up plans together. This requires dialogue and consensus-building. Monitoring is central to PGRAD because plans must be adapted as needed, to support processes for evolving and strategic planning. |

Gender-responsive planning means first learning about how gender shapes the opportunities and constraints that women and men face in securing their livelihoods within each cultural, political, economic and environmental setting. Because women and men have different tasks and responsibilities, and different livelihood strategies and constraints, they must each be listened to. There is overwhelming evidence that development must address the needs and priorities of both women and men in order to be successful.

Participatory planning means that local women and men speak for themselves. After all, it is only the local farmers who know the details about the local ecology, and of the linkages among their family members' activities in food and cash crop production with livestock, forestry, fisheries and artisanal activities. And only they know how these are managed and by whom, and under what constraints. The knowledge and practices of farmers need to be recognized by planners and built upon in development activities.

Taking on all these complex issues is not easy. Herein lies the dilemma for agricultural planners. On the one hand, understanding complexity is necessary to provide agricultural programmes and services that are truly responsive to needs and priorities. If we are not dealing with complexity we are not dealing with reality. On the other hand, it is not realistic to expect planners to deal with thousands, perhaps millions, of micro-level differences. What then, can they do? The easy answer is to say what "not" to do. It is not a matter of attaching gender and participation to existing planning processes - these are not simple add-ons (Sheperd, 1998). It is the entire process of agricultural development planning that must change (and is changing). Any agricultural development institution contemplating adoption of a PGRAD approach soon re-cognizes that methods and training alone will not convert a conventional, technically-oriented, bureaucratic institution into a more gender-responsive, learning-oriented, strategic organization. The institution's mandates, management procedures, reporting systems and supervisory methods must also be reoriented.

We find women and men evolving farming systems which are non-linear, multi-story, sequential, interactive, and mixed and managed in many different ways, forming and fitting micro-environments, making their land more heterogeneous and its enterprises more diverse, and multiplying labour-intensive internal linkages. All these demand a continuity of intensive management. All move in a direction opposite to the simplifying, standardizing, management- and labour-sparing farming systems of industrial and green-revolution agriculture.

- Chambers (1997:170)

Planning requires looking forward. It is largely a creative activity. But planning also has a concrete impact. It involves mobilizing resources and people, often in large numbers, to do new things. That is not to say that we make plans without looking back - reflecting on past experience and events - or looking around - learning from what other organizations have learned and identifying their best practices.

The world of agricultural development planning has not been standing still. New models, pressures and opportunities have emerged. The philosophical tide has turned away from concepts familiar to planners, such as order, sequence and predictability, towards new less manageable concepts such as variability, risk and diversity.

In addition to gender and participation, a responsive planner builds upon other changes already taking place. He/she draws upon the trend towards decentralized planning and demand-driven agricultural services, which are well known to agricultural planners. Perhaps less familiar to many planners, but of great relevance to PGRAD, are the areas of strategic planning and progressive management for learning organizations. Ideas, principles and best practices from all of these areas, from both the public and private sectors, are incorporated into The Responsive Planner.

Decentralization makes the most sense when agricultural development has to deal with a multitude of complex issues. It is also a policy priority for many governments, driven either by changing political ideologies and/or by budget constraints. Decentralization means moving decision-making down the planning hierarchy where, to the greatest degree possible, operational functions and certain support services are transferred to intermediate and local government levels, producer organizations and civil institutions. The underlying principle is that decentralization should lead to increased efficiency because support services can meet producers' needs in a more timely and appropriate manner on the basis of local diagnoses.

Decentralization means moving away from an exclusively supply-based approach to development, led by centralized policies that take no account of local conditions, to one that is more demand-based (though not exclusively so). Supply-based policies are largely ineffective since they lack mechanisms for adjusting to the specific problems of each region, sector or type of producer. Centralized planning also means centralized information systems. When information is concentrated at the central government level, the rural population is prevented from knowing about the institutional, economic and technological environment in which they must develop, and therefore cannot play an effective role in planning.

While decentralized planning holds promise for increasing the responsiveness of agricultural institutions, it does not always do so. Decentralization can provide a policy context in which gender sensitive and participatory approaches are more likely. But decentralized planning can take many forms, some of which are not participatory. Local authorities to whom a range of powers have been devolved, in the fields of finance, policy design, and resource management, for example, can choose to accumulate rather than share power. In some cases, central governments encourage local authorities to use PRA and related methodologies to involve local people in research, planning and resource-management activities that are part of the process of implementing democratic decentralization. The governments of Bolivia, Uganda, India, the Philippines, Colombia and Mexico are all experimenting with ways of scaling-downgovernment and scaling-up participatory approaches.

More and more, farmers are being viewed as "clients" for whom agricultural services must be tailored. The definitions and roles of extension and extension agents are changing, especially because of the need to cover the information and training needs of a diverse, heterogeneous clientele. Public agricultural extension services are being restructured and reoriented in order to respond to the need for participation by a wide range of stakeholders, to improve responsiveness and accountability, including sensitivity to gender issues, and to include non-conventional messages that incorporate environmental issues. These agricultural services are decentralized and open to multiple delivery mechanisms, including delivery by private-sector enterprises, NGOs and producer associations. The result is called "demand-driven" or "client-responsive" agricultural services. This innovative approach is being incorporated into national extension systems that promote a variety of services and methods of delivery within a unified policy framework (Crowder, 1998).Vietnam, Ethiopia and Namibia, to name only a few, are countries experimenting with demand-driven agricultural services.

In the past, extension was simply expected to close the gap between what the farmers actually do and what they should do. Extension was automatically assumed to know what was best for farmers. But in a client-responsive extension system, the focus is on extension as a communication process. Are extension agents and farmers talking and listening to each other? Are they jointly and critically reflecting upon the applicability of the technologies at hand? Grandiose planning gives way to an effort to listen, learn and respond.

Another key concept in client-responsive extension is pluralism. It is increasingly acknowledged that the complexity of agricultural development demands an array of technological solutions and service structures, including a readiness to adapt and change these packages as situations change and understanding increases. Pluralism also means recognizing that farmers are not all alike; there can be tremendous differences in needs and priorities among farmers according to whether they are rich or poor, male or female.

The features and benefits of demand-driven agricultural services | |

Nielson and Crowder (1998) | |

DECENTRALIZED ADMINISTRATION OF FIELD

EXTENSION SERVICES |

EXTENSION SERVICES ARE COST-SHARED |

OUTSOURCED EXTENSION SERVICES |

EXTENSION SERVICES ARE INTEGRATED WITH

RESEARCH |

While agricultural development has been shifting from blueprints to participation, the parallel shift in the business world has been from mass production to flexible specialization. Standardization has been replaced by variety and rapid response.

The world's most successful companies, such as Apple, IBM, Honda and Royal Dutch/Shell, have had to turn their planning and management practices upside down and inside out, in order to survive. They have been driven by the discipline of the market and the opportunities and imperatives of new technology. In other words, they have had to respond to incredibly complex, diverse and changing situations. It is also remarkable that, after years of experimentation and adaptation (with perhaps the world's most highly paid management consultants) they have all settled on the same strategy: to become learning organizations (Bryson, 1995; Peters, 1987 and 1994; and Senge, 1994).

In learning organizations, people continually expand their capacity to produce extraordinary results. Learning is used to enhance abilities to respond rapidly to changes in development needs, with the procedural flexibility such changes require. It is a mix of both behavioural and technical disciplines, drawn from both the East and theWest.

The following are the core disciplines of the learning organization.

As the world becomes more interconnected and business becomes more complex and dynamic, work must become more `learningful'. It is no longer sufficient to have one person learning for the organization.... It's just not possible any longer to `figure it out' from the top, and have everyone else following the orders of the `grand strategist'. The organizations that will truly excel in the future will be the organizations that discover how to tap people's commitment and capacity to learn at all levels in an organization.

- Senge (1990:4)

Systems thinking: seeing things as a whole. The focus is on seeing inter relationships, for seeing patterns of change rather than static snapshots. It is also a set of specific tools, including feedback. Systems thinking is used for dealing with greater complexity and faster change. It helps planners see those structures that underlie complex situations and discern high from low leverage change.

Personal mastery: personal excellence and proficiency. It is a personal commitment to lifelong learning, always striving to do better. People with a high level of personal mastery never "arrive". They are acutely aware of their ignorance as well as their core competencies.

Mental models: recognizing the deeply ingrained assumptions, generalizations and mental pictures that influence how we understand our work and how we take action. Questioning our mental models opens us up to inquiry, reflection and learning.

Building shared vision: creating a shared understanding of what the institution is trying to achieve. Shared vision is vital for learning organizations because it provides the focus and energy for learning. An institution's vision defines its mission and clarifies its future course and priorities. Moreover an important and socially justifiable vision is a source of inspiration to its stakeholders, including staff members.

Team learning: aligning and developing the capacities of all stakeholders to create the desired results. It has three dimensions: i) to tap the potential of many minds in dealing with complex issues; ii) to support innovative and coordinated action, in which each team member knows that the others can be counted on to act in complementary ways; and iii) to influence other teams (at other levels), and vice versa, through dialogue, discussion and listening (Senge, 1990).

People working in learning organizations are working on themselves as well as working on their systems of operation. Decentralization of certain management tasks and responsibilities to field staff and beneficiaries is a practice that already has great legitimacy in the business world.

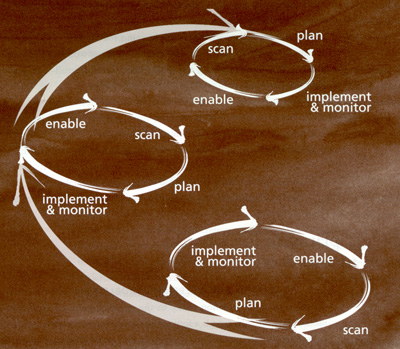

Strategic planning is a process designed to produce fundamental decisions and actions that shape and guide what an institution is, what it does and why it does it (Bryson, 1995). For the past 35 years, strategic planning has been a standard part of management practice in the business world. Only in the last ten to 15 years has strategic planning become the standard practice of large numbers of public and non-profit organizations. Strategic planning was introduced at FAO Headquarters in Rome, in 1997.

Compared to the logical framework traditionally used by agricultural development institutions (which is based on a model of cause and effect and not conducive to changing conditions), strategic planning offers a number of advantages. First and foremost, strategic planning allows planners to work with the realities of diversity and change. Second, it includes intense attention to all levels of stakeholders and their interests. Third, before identifying strategic issues to focus on, strategic planning requires the identification of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats posed by the environments both external (environmental, economic, political, social) and internal (policies, staffing, procedures) to the institution. Finally, through intense monitoring (by the stakeholders), strategic planning evolves. It is an iterative, rolling process - adapting as new needs and priorities emerge. In other words, there is not one plan, at least not for very long. Instead, there is a disciplined, realistic and responsive process of planning. Strategic planning provides a way of blending content and process.

Because The Responsive Planner has a global audience, and because conditions will be different in each specific planning situation, it outlines a planning approach that is process oriented and open-ended, while still giving some direction. This is risky. It assumes cooperation and support from and among policy-makers and planners at all levels, as agricultural development planning is not the job of any one individual. It also assumes that planners will adapt it, using their own creativity and skills to respond to their own planning contexts.

The ideas offered in this framework will be perceived by many planners as a support or articulation of actions already in process. For others, they may be perceived as a challenge or threat to current ways of working. Either way, this Framework is just a frame. It is one proposal for structuring a core set of ideas, principles, issues and questions into the planning process. It can be a beginning or it can be a stepping stone. As planners gain more experience in facilitating PGRAD, the subject will surely grow and change.

All planning frameworks are constructed on the basis of certain assumptions - and these assumptions need to be stated clearly. The Responsive Planner's greatest assumption is that planners are human beings, with both minds and hearts. For our minds, The Responsive Planner is based on best practices. It draws upon what has been proven to work-- in both the public and private-sectors. But it is also based on a value system that promotes equity and empowerment for those who currently suffer inequity and marginalization.

The Responsive Planner also assumes that planners do not mind a bit of innovation in their work. While planners see some of their roles and tasks changing, some even devolved completely, there are new roles and responsibilities to take their place. These new responsibilities are immensely important to successful participatory and gender-responsive planning and challenging to the individual planner.

WHAT IS THE ROLE OF THE PLANNER in PGRAD? The responsive planner is a proactive problem solver. He or she is not just passively planning, but actively seeks ways to enable practical actions to be taken faster. As learners, enablers and advocates, planners can create extraordinary responsiveness by practising decentralized and fast-paced facilitation across formerly sacred sectoral boundaries. The role of the planner is to make things happen.

What does it mean to be an agricultural development planner in an increasingly interdependent, interconnected and constantly changing world? It means that we must give up the presumption that we know exactly what we are doing. We do not - and we cannot - know everything necessary to formulate plans that meet the highly complex and ever changing needs of women and men farmers. This is because we are unavoidably ignorant in at least three ways.

1) We do not fully understand the complex realities in the field. We have no viable theories of change that fully acknowledge economic, environmental, social, technological and political linkages. We cannot even predict agricultural production beyond the next season.

2) Even if we had all the information we would still disagree about its implications. There are always multiple theories as to why conditions are as they are and no way to settle on the one simple interpretation.

3) What we choose to pay attention to, to seek or to avoid is strongly influenced by our professional training, education and experience. Even as we claim rational reasons for what we do or do not do, we may be missing important points, because we tend to focus on what is familiar to us.

Each planner must challenge conventional wisdom, especially cause and effect relations that have been considered axiomatic. Since new truths are not yet clear, the planner must become a good learner. We must learn to see planning as a learning process. Therefore we must see ourselves as learners, and allow others to see us as learners. This may not be easy at first. Many planners have received a lifetime of training in being forceful, articulate advocates and problem solvers. We know how to present and argue strongly for our views (backed up by piles of data). But when we are forced to deal with more complex and interdependent issues (such as household food security) we begin to realize that no one person knows the answer. The most viable option is to work with our clients (women and men farmers suffering food insecurity) to arrive at the most promising strategies.

To meet our responsibilities as learner-planners, we must become obsessed with listening. Responsiveness requires listening. Listening to farmers must become every planner's business. Listening is strategic. It reveals the big and little things that can pose stumbling blocks to responsiveness, equity, efficiency, etc. The listening learner-planner is the one most likely to quickly perceive changes in the environment.

It takes two Chinese characters to represent the word "learning". The first character means to study. It is composed of two parts: a symbol that means, "to accumulate knowledge," above a symbol for a child in a doorway. The second character means to practice constantly, andit shows a bird developing the ability to leave the nest. The upper symbol represents flying; the lower symbol, youth. For the Chinese then, learning is ongoing

- Senge et al., (1994)

Listening is not simple. Since it must be practised if we are to be effective learners, it must become a mindset. Our ways of listening must change - and new ways must be created. Traditional modes of listening- such as ministry meetings, donor meetings, village meetings and national meetings - are important. But new modes also are needed, because the numbers and diversity of peoples to whom we listen must be broadened. For example, we must ensure that we are tapping into women's listening posts. We must also make sure that we are listening to and learning from those working closest to the farmers, such as extension workers and community group leaders. They must get a thorough hearing with those higher up the planning ladder. We must also find ways to listen directly to women and men farmers. We must listen to them frequently. We must listen systematically - and unsystematically. We must listen for facts - and for perceptions. We must listen "naively".

Seeing ourselves as learners is a long-term approach of continuous listening and continuous adaptation. We should always seek to learn more about how to create extraordinary responsiveness.

Characteristics of good learners |

Good learners get out from behind their desks and go to where the

farmers are. They spend a minimum of four weeks annually in the field. They join PRAs, local stakeholders' workshops,

field demonstrations, etc. Listening and learning are part of their terms of reference. |

Good learners provide quick feedback on what they hear. They act on what they hear.

There is a "surprise factor" in the participatory process that causes difficulties for traditional models of planning. While a programme may be geared up to deliver, crop protection activities, for example, a PRA exercise may reveal that the farmers have a completely different set of priorities. How should planners respond?

It is common sense to start with local perspectives. We must keep our focus on enabling women and men in communities and local institutions to define and interpret their own realities and not interpret for them. Our job is to respond with the best services and programmes that we can offer. But this is seldom a straightforward job.

In truly participatory approaches (which are rare), the menu of development options is wide open. It is up to the farmers to decide what they want from development. But a word of caution is warranted here: participatory activities will have little impact if the participants do not have access to relevant information. Rural people, especially women, often have limited exposure to development options; they may be unaware of new marketing or employment opportunities, new methods for increased production or improved technologies. Women may ask for tie-and-dye training, not because this is a truely lucrative activity, but because it is the only activity they are aware of. For this reason, as a PGRAD enabler, planners must ensure that communities are exposed to an expanded menu of viable development options (including their relative costs, benefits and risks) so that participatory plans will be based on informed choice.

Even in objective-focused participatory approaches, which are increasingly common (such as participatory programmes for household food security), the range of relevant problems and priorities that may be raised by various groups of farmers is very large. As PGRAD enablers, planners must be ready to facilitate the delivery of a wide variety of technical services. And these cannot be limited to tidy sectoral boundaries, say fisheries here and livestock there. Sectoral boundaries are meaningless to farmers. The highest priorities of many agricultural development programmes today, i.e. household food security and natural resources management, require coordination across sectors.

As enablers, planners should spend a majority of their time seeking ways to make the whole system of agricultural services more responsive. First, planners must ensure that women and men farmers have access to relevant information. Second, planners must become expeditors, barrier destroyers and facilitators. Our role is to find ways to speed up actions, especially those actions requiring cross-sectoral and inter-institutional cooperation. Planners work to eliminate the sectoral barriers or traditional roles that constrain, prevent or slow actions.

Agricultural development planners do not live by pie charts alone - nor by bar graphs nor three-inch statistical appendices to 300-page reports. We live, reason and are moved by true-life conditions, principles and personal ethics.

Principles and ethics mediate all of the actions of agricultural development institutions, of UN agencies, of governments, of NGOs. But assumptions that planners working within big bureaucracies are just paper pushers tend to overlook the fact that many sincerely care about the impact of their work. There are countless agricultural development planners who are motivated, at least in part, by altruism and their aim is to make things better for those who are less fortunate or in need.

A key role for responsive planners is to advocate empowerment with equity. Empowerment with equity increases the involvement of socially and economically marginalized people in decision-making that affects their lives. The assumption is that participatory approaches empower local women and men with the skills and confidence to analyse their situations, reach consensus, make decisions and take actions that will improve their circumstances.

Definitions of empowerment |

(Crawley,1998:25-26) |

Empowerment is about people gaining the

ability to undertake activities, to set their own agendas and change events. |

But empowerment without equity is a risky business. Whether empowerment is good depends on who is empowered and how their new power is used. If those who gain are outsiders who exploit, or a local elite that dominates, the poor and disadvantaged may be worse off (Chambers,1997). Without concern for equity, the tendency would be for men rather than women to be empowered, the better-off rather than the worse-off, and members of higher-status groups rather than those of lower status. The challenge is to advocate a process in which the weaker are empowered and equity is served.

Paying attention to equity means paying attention to poor rural women, as well as others who are socially and economically marginalized. We know this is important because we have learned that misunderstanding or ignoring women's needs not only affects the women themselves but also has a negative impact on the immediate family and the wider community. We have also learned that an appropriately constructed equity approach, which is basically an inclusion approach, can help raise women's confidence, open up space for their views and ease oppressive gender relations.

Equity can be defined as that which is fair and just. Equity is not the same as equality because equity represents value judgements about what is fair, whereas equality is about being exactly the same in quantity, degree or value.

- Ingles, Musch and Qwist-Hoffman, 1998

While planners are not in a position to empower rural women and men directly, we can create some of the conditions that enable equitable empowering processes to take place. All too often (inadvertently and unaware perhaps) we do the opposite - undermine or create tough barriers. Good practice: advocate empowerment with equity which is a valid objective for agricultural development programmes. The advocacy can take many different forms. Planners can advocate empowerment with equity in speeches, programme documents and policy papers. It is even more important for planners to ensure that everyone is listening to women and other marginalized groups, and that relevant information and services are directed to them. At every stage of the PGRAD process and during every meeting, whether national, district or local, we must always ask the tough questions: Who is participating? Who is benefiting? Who is not? Why not? and What can we do to improve the situation?

With a goal as ambitious as creating extraordinary responsiveness to the complex and ever changing priorities of farmers, planners need proven strategies for getting started. The strategies given below are based firmly on lessons learned from the business sector and from evaluations of agricultural development programmes.

All too often we focus only on what is wrong and what is missing. It is even more important to identify, value and affirm that which works and has gone well within the context of our agricultural development institutions. Amplify the best of what is already practised. Start by locating and illuminating the reasons programmes or activities were especially responsive, where staff had exceptional commitment to meeting the priorities of women and men farmers. Seek to discover the factors and forces which allowed them to be so responsive. 2 These resources - actual experiences and skills - are powerful seeds and momentum builders with which planners increase their responsiveness.

An organization that reflects good capacity is somewhat like a festive curry meal. Making the meal requires skills, dedication, fresh ingredients, and good timing. There are staple ingredients that are understood as being essential - transparent management systems, clear communication, participatory work approaches - but there are also specific ingredients and spices that can only be selected by the people of that place. And, in the end, it is only they who will be able to put all the ingredients together in a recipe, select just the right cooking utensils, and make a curry that will truly reflect what they and their communities enjoy most.

- William Postma (1998:60)

The extraordinarily responsive planner is a clearinghouse and walking newsletter, a diffuser of best practices, passing on and sharing success stories, so that efficient learning throughout the entire system is facilitated. Such planners assiduously seek out examples of cross-sectoral multi-functional activities that went smoothly and fast, under ordinarily complex and trying conditions. We find out who makes it happen and praise him or her- as an example to others. Learning from experience - with a focus on positive experience - ensures that we do not plan the future on the basis of whims and fashions, but rather on plans planted in firm and fertile ground.

In PGRAD, we recognize that communities are neither homogeneous in composition nor concerns, nor necessarily harmonious in their relations. We use gender analysis as a planning tool to understand how gender influences the roles and relationships of people throughout all their activities, including their labour and decision-making roles. It is also important for understanding the position of women and men relative to one another, and vis-à-vis the institutions that determine their access to land and other resources, and to the wider economy.

Many participatory development programmes have not dealt adequately with the reality of community differences, including age, wealth, religion, caste, ethnic and, in particular, gender differences. Looking back, it is apparent that "the community" has often been viewed naively, as an internally equitable collective. Too often there has been an inadequate understanding of the internal dynamics and differences that are so crucial to positive outcomes (Guijt and Shah, 1998).

It is well-documented that development efforts in which women are marginalized are destined to fail. Using gender analysis helps planners establish an environment in which women and men can both prosper. Gender analysis, in other words, never focuses only on women. Good practice: include an analysis of both women's and men's positions, views and priorities. We seek to understand the constraints and priorities of both women and men, relative to one another, focusing on where they overlap as well as where they differ.

Gender analysis helps us learn about diversity. A frequent mistake is to assume that gender analysis treats women and men as single identifiable categories. Not so. Good practice: combine an analysis of gender differences with other locally meaningful differences - such as caste, ethnicity, race and wealth.3 It is called gender analysis because within any single socio-economic category, e.g. low caste agricultural labourers, there are always gender-determined differences that have important implications for development.

Gender analysis helps us break away from stereotypical assumptions and generalizations about what women and men do, and what they want from development. It helps us focus on the facts. Therefore it also reveals how the constraints and priorities for agricultural development may vary from one village to another, and among various groups of people within a village.

This does not mean communities are not important to agricultural development. They certainly are. But the assumptions of homogeneity or harmony have been replaced with recognition of multiple interests within communities. We have learned to love diversity and to recognize its implications for creating extraordinary responsiveness. In PGRAD, we emphasize "specialist" rather than "mass" or "blueprint" thinking.

Change, by definition, means disruption. Both the macro- and micro-level contexts for PGRAD planning are rife with change. Agricultural development institutions have become more tightly interconnected with volatile economic, environmental, political and social changes. These changes reverberate at every level of society - from village to state and beyond. Every place is different from every other place - and every place is changing.

While some changes, such as those brought by natural disasters, are swift, others are gradual. One of the gradual changes is the shifting dynamics of gender relations. Changes in gender relations are by no means a simple issue. They are interconnected with environmental, economic, technological, political and social changes. But they can have profound effects on the success or failure of agricultural development. Nor can it be assumed that these changes are always bad. Girls' increasing access to education, for example, is a positive change.

In many parts of Africa, a worrying gender issue is the absence of useful social and economic roles for men in the face of high unemployment, and their loss of traditional activities which contributed to their households' well being. This has negative effects for men, women and children in terms of their household food security. Dealing with this kind of change with a gender-responsive approach means seeking to respond with services which benefit all individuals within the household. It may, for instance, be of top priority (to both women and men) to increase the dry-season production options of men.

Acknowledging change challenges traditional planning models. Complexity, ambiguity and diversity can be difficult for planners. Under conditions of continuous and accelerating complexity and change, how can we plan agricultural development programmes and services that will be extraordinarily responsive?

At the micro-level, participatory methods help us learn about change. For agricultural development planning, participation means farmers analyse their own problems, prioritize their own options, and plan, implement and monitor their own development activities. Good practice: a participatory analysis of change with a cross-section of women and men, including changes experienced (e.g. deterioration in the natural resource base, new economic opportunities) and changes desired (e.g. improved fodder production, increased access to clean drinking water) (Wilde, 1998). Over time, the very act of participating in development activities creates important physical, economic and social changes, e.g. an expanded irrigation system, or empowerment of the most marginalized groups to plan their own development activities.

For dealing with macro-level changes, progressive business managers use systems thinking. Systems thinking is a discipline for seeing the whole picture, for seeing interrelationships rather than linear cause-effect chains, for seeing processes of change rather than snapshots of the moment. Because it helps planners see the structures than underlie complex situations and to discern high from low leverage change, systems thinking is used for dealing with greater complexity and faster change (Senge, 1990:68-69).

Success will come to those who embrace change - constant change - not those who attempt to eliminate it. Stability and predictability are gone forever (they never really existed) and therefore must not be the implicit or explicit goals of agricultural development plans. We can master change by focusing on patterns and processes, and by constantly working on responsiveness and enhancing the capabilities of others to do so. We must learn to see changes as opportunities.

If you place a frog in a pot of boiling water, he will immediately try to scramble out. But if you place the frog in room temperature water, and don't scare him, he'll stay put. Now, if the pot sits on a heat source, and if you gradually turn up the temperature, something very interesting happens. As the temperature rises, the frog will do nothing. In fact, he will show every sign of enjoying himself. As the temperature gradually increases, the frog will become groggier and groggier, until he is unable to climb out of the pot. Though there is nothing restraining him, the frog will sit there and boil. Why? Because the frog's internal apparatus for sensing threats to survival is geared to sudden changes in his environment, not to slow, gradual changes.

- Senge, 1990

Faced with the complexity, diversity and dynamism of gender-participation issues in combination with volatile environmental-economic-political-social conditions, it is only to be expected that mistakes will be made. But errors that are recognized and embraced can lead quickly to extraordinary responsiveness. Lessons from mistakes are needed to "fail forward"-- to learn to do better (Peters, 1987).

Responsive planners must be open to learning from mistakes, always seeking to do better next time. Such an attitude requires a high degree of critical self-awareness and willingness to embrace error. The latter is perhaps the most difficult personal attribute to develop (Chambers, 1997). Professional insecurity and career pressures usually lead us to hide or minimize the errors we commit, be they of judgement or action.

If we don't make utter fools of ourselves from time to time, we grow smug - that is, we do not grow at all.

- Peters (1994:278)

Learning depends absolutely on embracing error. The most competent planners know that errors will happen as plans are implemented. They design mechanisms for participatory monitoring in advance so they will learn about mistakes as soon as they occur, and use the resulting understandings to continually adjust the plans. Failing forward is an operational precondition for responsiveness - the capacity to learn from errors, adjust and improve.

Embracing complexity, continuous learning and always seeking to improve - these words cannot be repeated enough. No one denies where the answers are: in the field. Unfortunately a certain distance is institutionalized between planners and the field. This distance blocks, blurs and distorts understanding. Many big mistakes have been made in agricultural development programmes -usually because they were designed by those who were physically, organizationally, socially and cognitively distant from the people and conditions they were planning and prescribing for (Chambers, 1997).

What are the practical implications? Rethink control. The long-term success of a participatory process depends more on the skills and enthusiasm of the field staff than on any other single factor. In learning organizations, the organizational chart looks like a reverse pyramid, with field-level people on top and supervisors and planners below them in a support and facilitation role. In other words, we must defer to those who are in the field or close to the field. The job of all responsive planners - from national to district levels - is to enhance the ability of the field staff to do its job better. The most effective planners empower others to act and grow. In a traditional hierarchical organization, the top level thinks and the local level acts. In a learning organization, we have to merge thinking and acting in every individual.

Ironically, the most lightly regarded staff in agricultural development organizations, public or NGOs, are those who are closest to the farmers and most directly responsible for the quality and responsiveness of services delivered. This must change if total farmer responsiveness is to become reality. The responsive planner spends time with field staff members, gives them recognition, listens to them, empowers and trains them, and gives them the technical support they need, making sure that the systems are in place which allow them to do their jobs to the fullest extent possible.

Deferring to the field means unleashing field staff's commitment by giving them the flexibility to act rapidly, to respond directly to farmers' needs and to be responsible for the results. We must delegate to act horizontally too. Delegation has traditionally meant pushing decision-making to the lowest level. But there is another level of delegation which is growing in importance--delegation to farmers and to field staff as part of a horizontal planning process which seeks fast connections with other women farmers, farmers' groups, entrepreneurs, etc. and across sectoral functions without having to check up the ladder first.

|

Leadership Still Counts - The Myths of Participatory Management | |

(Barlow, 1998, based on Harvard Management Update April Edition) | |

Myth No. 1. Shared management means eliminating conflict among staff. In fact, with more ideas expressed, there may be more conflict. This clash generally produces better ideas. |

Myth No. 6. In a bottom-up organization, the boss has to accept what his or her underlings decide. Despite shared responsibility, the boss still has final responsibility. Actually this isn't the real problem. Underlings often spend their time trying to evade responsibility, not take more of it. The leader must invest time encouraging them to make decisions. |

Myth No. 2. It's a soft way to manage. In reality, it's a hard way - perhaps harder for those at the top than when they simply told everyone what to do. Managers must encourage field staff to make decisions and take responsibility for their actions. And the boss must admit at times that he or she doesn't know all the answers. |

Myth No. 7. Team commitment to a decision is more important than the quality of the decision itself. Not in the real world. As long as there is need for any organization's services, good decisions must be made. Just bear in mind that there is no such thing as a perfect decision. And the old cliché about two minds being better than one became a cliché because it was true. |

Myth No. 3. The emphasis on collaboration means the end of competition among staff members. Indeed, such competition can and should continue. The leader's challenge is to keep that competition focused on performance, not on internal politics. |

Myth No. 8. The team may make the decision but the boss has the vision. Involvement by the team usually means a better vision - since team members bring a wide variety of knowledge into the process. |

Myth No. 4. Under this kind of management, the boss no longer makes decisions. He or she still does. The difference is they may not necessarily be his or her decisions: "Our job today is to determine how we are going to cut the budget," not, "Keep guessing until you arrive at the cuts I want". |

Myth No. 9. It takes forever to reach decisions. The meetings to decide might last longer. But leaders no longer must spend hours lobbying individual members before and after meetings to get the decision they want. |

Myth No. 5. The boss never makes autonomous decisions. Autonomous decisions usually come on rare occasions when the boss has privileged information, or when everyone else gets bogged down in a trivial matter and the boss needs to get everyone focused on more important matters. |

Myth No. 10. It takes a long time for bottom-up management to achieve results. Research shows just the opposite. Immediate good results are usually apparent. And in the long run, as the teams gain more experience, the quality of those decisions get better. |

PLANNERS DO NOT WORK IN A VACUUM. They work within institutions - generally large bureaucracies - where the cultures, procedures and methods of operation are far from conducive to PGRAD. How can a large agricultural development bureaucracy support and encourage its planners to create extraordinary responsiveness? How can a gender perspective be promoted and sustained to the point that it is institutionalized and still remain responsive to the variety of women and men's experiences and priorities? Through people. People must become the primary source of value added, to be optimized.

Like everything else, institutions have a culture and this culture exerts great influence on what can and cannot be accomplished by their staff members. Institutionalization of PGRAD requires a "rapid response task culture" that draws planners, policy-makers, programme managers and farmers into a relationship that is cooperative and action-oriented.

It is the "role culture", not the task culture, which is typical of large bureaucracies (Handy, 1993). The role culture - which works by logic and rationality - can be illustrated as a Greek temple. The institution rests its strength on its columns, which correspond to sectoral functions or specialities. The work of the columns, and the interaction between the columns, is controlled by clearly defined roles (e.g. job descriptions), procedures for communications (e.g. required sets of memoranda) and rules for decision-making. They are coordinated at the top by a narrow band of senior management, the pediment. If the separate columns do their jobs, as prescribed by the rules and procedures, this should be the only coordination needed-and the ultimate result will be as planned.

The Greek Temple |

|

This Greek temple institution will succeed as long as it operates in a stable environment. When next year is like this year, so that this year's rules will work next year, then the outcome will be good. But Greek temples are insecure when the ground shakes, i.e. there is change. Role cultures are slow to perceive the need to change and slow to change even when the need is seen.

The task culture is job or project orientated. Its accompanying structure can be best represented as a net, with some strands thicker and stronger than others. Much of the power and influence lies at the interstices of the net, the knots. The task culture seeks to bring together the resources, the right people at the right level, and let them get on with their jobs. Influence is based more on expertise than on position. Influence is also more widely dispersed and each individual tends to think he or she has more of it. The task culture is adaptable. Groups, project teams or tasks forces are formed for specific purposes and can be reformed, abandoned or continued, as necessary. The net institution works quickly since each individual has a high degree of control over his or her work, is monitored by results, and enjoys easy working relationships within the institution because relationships are based on mutual respect.

Agricultural development experience, including integrated rural development, multi-sectoral nutrition planning, farming systems research, national food security planning and poverty alleviation planning, has shown that the traditional role culture is not well-suited to such integrated, cross-sectoral, multi-sectoral or participatory programmes. In all cases, different departments have been thrown into conflict over priorities and resources, decision-making has been disrupted or slow, and planners and managers have been ill equipped to handle new levels of complexity (Maxwell, 1996).

One striking feature of the process approaches advocated by participatory development workers is that they correspond closely to a task culture approach. The key features of a task culture, namely innovation, flexibility, participatory leadership, result-orientation, are all found in process models for participation. Good practice: for institutionalization of PGRAD, shift from a role culture (hierarchical bureaucracy) which typically uses a blueprint approach to planning, to a task culture (learning organization) which promotes a process approach to planning.

In today's world, learning organizations and private-sector business managers prefer the task culture. With its emphasis on groups, expert power and rewards for results, it is the institutional culture most in tune with current ideologies of change and adaptation, individual freedom and low status differentials. But its virtues should not be exaggerated. When resources are not available to all those who are able to justify a need for them, when money and people have to be rationed, planners begin to feel the need to control allocations and to set priorities. Alternatively staff members begin to compete, using political influence for available resources. This new state of affairs necessitates procedures and planning processes to help managers and planners to make strategic decisions.

One of the most fundamental tasks for the PGRAD institution is to mainstream gender issues, not only in its fieldwork - but also inside its own offices.

The word "gender" is probably the most misunderstood word in development today. At best, many development planners see it as useless jargon, relegating it to that extra (but required) paragraph in programme and policy documents. At worst, it causes feelings of anger and hostility.

Gender can be defined as the social differences in female and male roles, rights and relations that are:

Gender issues are controversial because they are relationship issues - and therefore politically and culturally sensitive - not between individuals, but between classes of females and males. As a fundamental organizing principle of all societies, these relationships colour and mediate all forms of social and economic activity, at all levels. It is about understanding these relationships. Gender is about addressing dynamics that are harmful, inequitable and unfair. And it is about ensuring that both women and men have a say in their own lives.

Slowly, gender issues are gaining legitimacy in development institutions. It is increasingly recognized that gender issues are inter-linked with the issues of human rights, equity and fairness. Gender issues have also proven to be closely linked to efficiency and success. This link is especially strong in agricultural development.

|

WHAT DOES MAINSTREAMING GENDER MEAN? |

UNDP (1998) |

The legitimacy of gender equality as a

fundamental value is reflected in development choices and institutional practices |

Within all types of development institutions, women's exclusion is most striking in the case of agricultural institutions and services, despite the prevalence of evidence that women are central to agriculture in most agrarian economies. Across Africa for example, where women are responsible for 60 percent of total agricultural output and 80 percent of food production, they receive less than 2 percent of contacts with extension workers. It has also been observed that the bias against women farmers increases in intensity as the value of agricultural service increases. This is also true for other agricultural institutions such as marketing boards, research institutions and credit agencies. That these services overlook women raises serious doubts about the gender-neutrality of agriculture institutions (Goetz, 1992).

Before institutions can ensure gender-responsive outcomes on the outside, they must work on the inside. No matter how clear policies and responsibilities might otherwise be, without gendered procedures, the bureaucracy can undermine PGRAD. The lack of female staff, for example, has often proven a barrier to reaching women farmers. Good practice: make a "gender scan" of the organization at three levels: institutional mandate, organizational culture and structure, and human resources (Sprenger, 1996). This scan, useful for revealing where internal staffing and operational procedures may require adjustment, includes the following questions.

MANDATE

ORGANIZATIONAL CULTURE AND STRUCTURE

HUMAN RESOURCES

The capabilities required to institutionalize PGRAD are numerous, touching upon every aspect of work. While the task may appear daunting, the capabilities needed are already at hand. Lessons learned from both private and public sector institutions show the way.

Shifting the institution's entire orientation from vertical (hierarchical) to horizontal (fast, cross-sectoral, cooperative) is one of the most dramatic requirements of institutionalizing PGRAD. Horizontal thinking is partnership thinking. We must see agricultural development as a joint venture of stakeholders, including government, NGOs, donors, UN agencies and private business, while keeping the voice of women and men farmers in the centre of the process. Creating responsiveness is as much about inter-institutional change as it is intra-institutional.

Considerable knowledge is revealed when planners and practitioners from different areas come together to work for PGRAD. Everyone must look at the whole together. Good results in a complex system depend on bringing in as many perspectives as possible. By its very nature, PGRAD points out interdependencies and the need for collaboration. Thus, we must make sure that the institution is open to working together with all the relevant stakeholders to pave the way for fast, cross-sectoral solutions.

There is a Sufi tale about three blind men who encountered an elephant. It is a large rough thing, wide and broad, like a rug," said the first, who was grasping an ear. The second, who was holding the trunk, said, "I have the real facts. It is a straight and hollow pipe." And the third, who was holding a front leg, said, "It is mighty and firm, like a pillar." Are the three blind men any different from the directors of livestock development, fisheries and crop production in many agricultural development institutions? Each sees their sector's problems clearly, but none see how they interact with the others. The Sufi story concludes by observing that, "Given these men's way of knowing, they will never know an elephant.

- Senge, 1990

Establishing partnerships is especially important in the early stages of adapting to a gender-responsive and participatory approach, when many of those concerned will not welcome the changes. Good practice: twinning - pairing people or groups within and between institutions, and between levels in institutions, to support one another. The purpose is to establish a direct horizontal link between those facing similar challenges, in order to channel expertise and knowledge from one to the other, through regular, formal and informal contacts between colleagues on both sides. The strong point of this strategy lies in the horizontal and collegial aspect of the relationship, its flexibility, and easy access to regular advice. Twinning is most successful however if it has a clear focus, such as development of methods for participatory monitoring and evaluation.

There are few greater liberating forces than the sharing of information. Knowledge is power - it always has been, it always will be. Without the power of information, there will be no responsive action.

Those with less power, e.g. women and men farmers, tend to have less access to information and less power in defining what sorts of knowledge and information are useful in agricultural development. Many in this position also accept the superiority of the knowledge of those in more powerful situations, such as village leaders, extension workers and planners who often feel confident about the superiority of their own knowledge. One of the biggest contributions of PRA experiences to date has been its challenge to the superiority of professional knowledge over that of the non-professionals.

The world today is dealing with a host of new variables surfacing and changing at lightening speed. Therefore, the institutions of agricultural development must have access to a variety of information sources to match the complexities of the field, or risk being led to erroneous conclusions. The demands and complexities of PGRAD have at least two possible information-related risks: distortion and overload.

I think there is a world market for about five computers.

- Thomas J. Watson

Chairman of IBM 19434

Information distortion is a great peril of responsive planning. Most information used for agricultural planning, especially nationally and internationally, comes professionally packaged. But there may be many distortions behind the tidy columns and computer-generated graphics. Most information systems are designed to protect planners from trivia and complexity so that our minds are clear as we confront "big picture" decisions. Instead our minds are all too likely to be empty of all but the findings of the pre-packaged data, leading to uninformed decisions. One of the most pervasive examples is the lack of gender-disaggregation in agricultural statistics which can create enormous distortions in understanding field-level realities and lead to ineffective, even harmful, development programming. Good practice: include the use of gender-responsive PRA methodologies in addition to gender-disaggregated statistics.

Too much information can have a counter-productive effect, as no one will have enough time to digest it. Hence the importance of original presentations and summary reports that present only the most pressing issues. Macro-level development information flowing down to communities, and micro-level information flowing up from communities to planners needs to be made user-friendly. Horizontal channels of communication and information sharing - farmer to farmer, women's group to women's group, NGO to NGO, etc. also are key to PGRAD. Having the capacity to ensure adequate information transfer, vertically and horizontally, is a priority and should be built into the institution's routine functions.

Communication media can help overcome barriers of information access, illiteracy, language, inter-cultural differences and physical isolation. Good practice: well-designed communication strategies that establish dialogue with rural people, involve them in their own development and relay information useful for improved farming. Key strategies and media tools for improving the dissemination and sharing of agricultural knowledge include rural radio to reach remote audiences, video for training illiterate farmers, multi-media campaigns for widespread dissemination of better practices, and, where available, tele-training and electronic networking using the new information technologies. The challenge is to combine the use of communication media with audience participatory processes in order to achieve empowerment through information sharing. The challenge is also to ensure that women and other marginal groups have full access to these communication channels.

The Power of Information |

Gender-disaggregated PRA information and gender-disaggregated

statistical information provide critical confirmation that the institution sees women and men farmers as partners and

problem solvers. The absence of such information confirms the farmers' invisibility in agricultural planning. |

When people are seen as the prime source of value added, it becomes clear that they can never be trained too much.