Abbreviations and Units

A. WATER AVAILABILITY AND USE

B. WATER INSTITUTIONS AND LEGISLATION

C. DEALING WITH WATER RIGHTS IMPLEMENTATION ISSUES

D. THE WATER RIGHTS ADMINISTRATION SYSTEM: A PRE-REQUISISTE FOR THE SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT OF WATER RESOURCES

E. USEFUL POINTERS FOR THE FUTURE OF WATER RIGHTS ADMINISTRATION

References

|

The materials in Garduño 1997a, 1997b, and 1999 have

been summarized and consolidated in this report. The author has made some

additional analysis of the Mexican experience, updated progress as of March 1999

and included lessons learnt from the perspective of other countries that might

benefit from them. |

|

FAO |

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United

Nations |

|

FWLL |

Federal Water Levy Law |

|

NWC |

National Water Commission |

|

NWL |

National Waters Law |

|

O&M |

Operation and Maintenance |

|

SGAA |

Subdirección General de Administración del

Agua, (Sub-Directorate-General for Water Administration) |

|

WRPR |

Water Rights Public Register |

|

km3 |

cubic kilometer |

1.1 Mexico is an extremely varied country in terms of both geography and climate. It is often the physical terrain which in fact determines the climate, although there are also seasonal changes which are most marked by the summer rainy season (June to October). Mexico lies within the tropical belt and contains many mountainous areas as well as valley and plateau regions.

1.2 Its two great mountain ranges are the Sierra Madre Occidental in the west and the Sierra Madre Oriental in the east. They run parallel down to the coasts, enclosing a high semi-desert plateau and about half way down they are crossed by the volcanic highland area in which stand Mexico City and the major centers of population. The mountains run together as a single range through the southern states of Oaxaca and Chiapas. Only the eastern tip of Mexico, in the Yucatan peninsula, is consistently low-lying and flat. The southeastern state of Chiapas is an area of tropical rain forest and is the wettest state in Mexico, whereas in the semi-desert north, the rainfall is very scarce. This temporal and spatial variability in rainfall is illustrated in figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 - Rainfall Variability in Mexico

1.3 The variability in rainfall is therefore a significant factor which determines the availability or scarcity of water throughout the Mexican Republic. The overall annual renewable availability is 450 km3 and in spite of the relative abundance of water in some regions the actual availability is restricted by the need for treatment. The hydraulic balance has therefore been described in terms of “real” water availability, that is water with the required quality for specific uses (Jiménez et al, 1998).

1.4 Mexico is a country with 95 million inhabitants with a concentration of more than 17 million within Mexico City. The average water availability is close to five thousand cubic meters per year, per capita, which is well above the international scarcity standard of one thousand. But temporal and spatial variability, as well as waste and pollution determine actual availability, which in turn gives rise to conflicts among water usage, users, states and regions. Given this situation, the implementation of an effective water rights administration is essential. The following account will review the setting up of such a system of administration and will focus particularly on the importance of regularization of existing water uses and wastewater discharges throughout the Mexican Republic.

1.5 In Table 1.1 the different categories of fresh water use in Mexico are shown in terms of annual abstracted volume in cubic kilometers, wastewater discharge and estimated number of users.

Table 1.1 - Water Uses in Mexico

|

|

Volume (km3/year) |

Estimated number of users |

|

|

Abstraction |

Wastewater discharge |

||

|

· Hydropower |

127.7 |

|

75 |

|

· Agriculture & Livestock |

66.1 |

0.60 |

126,200 |

|

· Urban & domestic |

12.8 |

620 |

161 900 |

|

· Industry & services |

6.3 |

1.70 |

12,800 |

|

· Aquaculture |

1.1 |

0.40 |

600 |

|

· Thermopower (Mostly cooled by

sea water) |

2.2 |

4.46 |

47 |

|

|

216.2 |

13.36 |

301,622 |

1.7 From 1993 to mid 1995 the progress in regularization was rather slow because the legal and regulatory requirements were difficult to comply with and the National Water Commission did not have enough capacity to manage the regularization within the transition period provided by the law and its regulations. It was thus deemed necessary to simplify the requirements to obtain and register a water concession title and a waste discharge permit. Two presidential decrees passed in October 1995 and October 1996 simplified such requirements and, among other benefits granted, sanctions were waived for users who had been without concession and applied for one. (See Box 1.3). The Presidential decrees were the key instruments in accelerating the regularization process (Figure 1.3). Further details are given in paragraphs 1.21 to 1.28.

i. Background

ii. Current Organizational Structure

iii. Legal Bases for the Water Rights Administration System

1.8 Before the Spanish conquest in 1521, the relationship of the Mexican peoples to water was both religious and practical. The fact that there were several water deities leads to the belief that water was regarded as a public resource not as a commodity that could be privately owned. Practical realities made it necessary to establish norms in order to define who could use water, how to resolve conflicts among water users and how to cope with floods. Water supply aqueducts, irrigation works and flood control works and navigation systems were all constructed. After the conquest, water for 300 years belonged to the King and a royal grant was required to use it. These rights passed to the State on independence in 1821. The present Constitution dates to 1917 following the 1910 revolution. It recognizes the nation as owner of all water within its territory with a few exceptions and authorizes the government to administer these resources and grant “concessions” for water use (Article 27). Box 1.1 highlights the main features of Article 27 related to water rights administration. Municipal governments, with assistance from state governments, are responsible for municipal water delivery systems (Article 115, amended in 1985).

Box 1.1 - Main Features of Article 27 of the Mexican Constitution Related to Water Rights Administration

|

The Nation has had and has the right to transfer the domain of land and water in order to constitute private property; All surface and groundwater, except that which flows through a single property or lies beneath it, belongs to the Nation; All groundwater whose use has not been prohibited, regulated or reserved by the Federal Executive, can be used without a concession; The domain of the Nation upon water is inalienable and imprescriptibly; The only legal way to use national waters is through a concession granted by the Federal Executive; The Federal Executive has the power to establish and suppress prohibitions to use national waters; All water concessions granted from 1876 to 1917 which violated the rights of communities, are null and void; and All contracts stipulated from 1876 to 1917, which monopolized

water, are subject to revision. |

1.10 The law defined the NWC as “the sole federal water authority in the country”. Initially it remained attached to the Ministry of Agriculture and Water Resources but it was transferred in 1995 to the new Ministry of the Environment. The international consensus that “water use management should be based on a well tuned combination of regulatory, economic and participation instruments”, is clearly reflected in the main laws that constitute the Mexican water legislation. These are: the NWL and those sections of the Federal Tax Law that are related to water, which will be addressed in this paper as the Federal Water Levy Law (FWLL).

1.11 The 1992 NWL calls for an integrated approach to both water quantity and water quality management of surface and groundwater, within river basins which are considered to be the ideal geographical units for planning, development and management of water resources. However, when established, the NWC was organized on an administrative boundary basis. Six regional agencies which grouped states were created, along with agencies in each of the 33 states.1 The regional agencies have been recently reorganized broadly along river basin boundaries. Mexican rivers are typically numerous and short, falling from the central mountains to the Atlantic Ocean in the east and the Pacific Ocean in the West. They have been grouped into thirteen river basin agencies, the boundaries of which still follow municipal limits since it was felt that no municipality should have to deal with more than one river basin agency. Subject to this constraint, the regional agencies follow hydrological boundaries as closely as possible.

1 In fact there are 32 states and one Federal District (which is part of Mexico City), but for the sake of simplicity they will all be referred to as “states” in this report.1.12 This boundary re-definition is consistent with the widely accepted international principle of river basin planning and management, which has been incorporated in the Mexican water legislation. However there are now several states that in order to address their water issues have to deal with more than one river basin agency. The following challenges will have to be faced in order to make the principle operational: (a) developing technical and managerial capacity for the increased number of agencies, (b) modifying procedures and information systems (technical and managerial) in order to fit the new territorial organization, (b) establishing an adequate communication and negotiation strategy and mechanisms between the NWC and state Governments.There are three shared rivers with the USA that are covered by a treaty that allocates the water on an “equitable” basis between the two countries and is implemented through the International Boundary and Waters Commission. This commission is also responsible for the joint construction and operation of flood control, diversion and river channel facilities and maintains a data collection system.

1.13 The regulatory, economic and participatory instruments that can be found in the NWL are highlighted in Box 1.2.

Box 1.2 - Regulatory, Economic and Participatory Instruments in the National Waters Law

|

Regulatory Instruments · Implementation of water resources planning as the basis for management within river basins. · Reiteration of the constitutional principle that water can be exploited by individuals or legal associations only by means of a concession granted by the Federal Executive through the NWC for a period of 5 to50 years. The law: (i) defines specific regulations for the principal uses (irrigation, water supply, sewerage & wastewater treatment, power generation, and other productive uses); (ii) establishes criteria for the time limit of abstraction concessions, and cancels concessions that are not used within three consecutive years (to avoid speculation and monopoly); and (iii) provides for enforcement of efficient water use, with due sanctions to users who apparently waste water. · Power of the Federal Executive to limit or prohibit use in the national interest: (i) to prevent or remediate groundwater overdraft, (ii) to protect or restore an ecosystem, (iii) to preserve sources for water supply or protect them from pollution; (iv) to preserve and control water quality; and (v) at times of drought or severe water scarcity. · Water pollution prevention and control, in that all users who dispose of wastewater must: (i) obtain a discharge permit and comply with the specified discharge standards; and (ii) inform the NWC how they will comply with the standards. · Regulations to manage: (i) the use of federal zones (defined as a strip of land along a river or lake 10 meters wide above the level of the maximum normal flood); and (ii) extraction of sand and gravel from a river bed. · Users who do not pay the charges specified in the FWLL for water abstraction or wastewater discharge permits are subject to cancellation of their concessions and permits. · All abstraction concessions, federal zone occupation, discharge permits and water rights trades must be recorded in the Water Rights Public Register in order to provide users with legal certainty. · Sanctions to users for not complying with the NWL or its by-laws. Users have the right to appeal against NWC resolutions and to use administrative procedures before resorting to the courts. · Transitional measures so those users who have documents other than concessions and permits but are de facto users, can regularize their legal situation. Economic Instruments · User obligation to pay the charges established by the FWLL regarding water abstraction, wastewater disposal, use of federal zones and use of sand and gravel as building materials. Also concessionaires of hydraulic infrastructure must pay certain charges. · Tradability of water rights (including abstraction concessions and discharge permits) to promote economically more efficient water allocation. Participatory Instruments · Establishment of river basin councils, as coordination and agreement units of federal, state and municipal authorities, as well as water users and all stakeholders. Their main tasks are to participate in planning and development of water resources, as well as in management particularly to cope with scarcity and pollution problems. · Establishment of water users organizations, mainly through divestment of Government-run irrigation districts and strengthening of water supply utilities · Promotion of social

participation in design, construction, financing and O&M of hydraulic

infrastructure and services. |

· The obligation to have a concession and a discharge permit in order to use water and discharge wastewater into a water body or into soil of national property, along with the obligation to pay water charges even for those who do not have said concession and permit.31.15 The FWLL defines the tariffs for using public goods or for services provided by the State. Thus, in addition to setting the rates of charges for concessions and discharge permits, it also sets the price for bulk water, such as water supplied by the NWC to Mexico City.5 The FWLL thus complements the definition of economic instruments (in the NWL) by making operational the “user pays” and “polluter pays” principles. That is, the tariff for abstraction water charges depends on the specific use and the relative scarcity of the water source; and the tariffs for wastewater disposal charges depend on the pollutants load and on the use and vulnerability of the receiving water body. In addition to the Constitution, the NWL and the FWLL several other legal instruments that should be mentioned are: international treaties (notably with the United States), the Federal Infrastructure Law, the Federal Environmental Law, and Environmental and Water Supply Laws adopted by the legislature of each state.3 The NWL Regulations were amended by presidential decree in December 1997 in order to specify cases where concession cancellation for non-usage of water should not apply. Namely: (a) when the user is not legally responsible for not using the water, (b) force majeure, (c) when the user has invested to make a more efficient use of water and thus saves part of the volume to which he/she is entitled, (d) when the user’s installed capacity needs his/her entitled volume but he/she is still not using the full volume, (e) when it takes more than three years to develop the production capacity that will need the full volume to which the user is entitled.· The “de-concentrated” nature of the Mexican system. All regulatory and related authority originates in the powers of the central government. Nevertheless, this is balanced by the fact that administration of water use and of wastewater discharge is taking place via the river basin and state agencies of the NWC.· The full integration of functional responsibilities for water quantity and water quality, and for surface and ground water within one agency. Integration is at central, river basin and state levels.

· The high priority given to establishing a secure legal water right and to maintaining the Water Rights Public Register This provides certainty and security to the holder of the concession or of a discharge permit.

· The time limit on concessions, and their tradability.4 This provides for flexibility and anticipates the need for reallocation amongst users.

4 The NWL Regulations were amended by presidential decree in December 1998 stating that groundwater rights may be transferred separate from land property in such areas as the NWC shall determine. In January 1998, the NWC Director General published a notice in the Gazette approving such kind of transfers in regulated aquifers.· The powers given to the NWC to establish special administrative and reserve zones in the national interest. These may either be permanent (e.g. to manage groundwater, protect a water supply source, or establish a protected ecosystem) or temporary (notably during a drought).· The incorporation of the user pays and polluter pays principles within the Federal Water Levy Law, and the enforcement of payment through the Ministry of Finance, and

· The pragmatic approach to community participation and the devolution of service delivery to user-owned irrigation associations and autonomous municipal water utilities.

5 It should be noted that among its many responsibilities, the NWC builds, operates and maintains public hydraulic infrastructure, including dams, supply channels, pumping stations and other works. However, irrigation infrastructure and other service delivery have or are being transferred to irrigation districts.

i. General Procedure

ii. Regularization of Existing Water Uses

iii. Regularization of Existing Wastewater Discharges

iv. Collection of Water Charges

v. Water Rights Transfers

vi. Information System

vii. Monitoring Implementation

1.16 In order to fulfill its obligations regarding water rights administration, the NWC carries out the following activities:

· granting, modification or cancellation of concessions pertaining to national waters, federal zones and the use of gravel and sand from river beds;1.17 In order to carry out these activities the Sub-Directorate for Water Administration of the NWC has the following four central units in Mexico City:· granting, modification or cancellation of wastewater disposal permits;

· operation of the Water Rights Public Register (WRPR);

· monitoring of water abstraction, wastewater disposal and user compliance with legal obligations;

· detection of illegal users;

· determination of sanctions against users who violate applicable regulations;

· monitoring of payment of water charges and the submission of reports to fiscal authorities;

· conciliation or arbitration of disputes between water users; and

· updating of the water user database.

· water User Services;1.18 The interrelationship between a water user or applicant, the NWC and the Judiciary is represented diagrammatically below in Figure 1.2. For a detailed description of this diagram see paragraph 1.38.

· water Levy Collection and Control of Users;

· public Water Rights Registry; and

· evaluation and Development.

Figure 1.2 - Interrelationship Between a Water User or Applicant, the NWC and the Judiciary

1.19 Here it can be seen that in the event that the user is in disagreement with the NWC there exists the possibility of appealing against decisions. The work of the four central units is closely interrelated and together they are responsible for the administration of water rights and thus have a major impact on water use patterns in the country. In addition, there are 13 regional offices and 33 state offices, which are part of the NWC. The personnel in charge of water rights administration, including the central, regional and state level consists of 1900 persons; of these 40% are professionals and 60% support staff. Concessions and wastewater discharge permits are issued according to the following criteria: (a) state agencies issue them for relatively small volumes in non-stressed river basins and aquifers; (b) regional agencies issue them for medium sized volumes in stressed areas and in areas where there may be conflicts among states; (c) the central level is responsible for the largest volumes, in cases where there may be conflict among regions and for transboundary waters.

1.20 As stated earlier, it was estimated there were about 300,000 water users by 1992 and only about 2,000 water use concessions were issued between 1917 and 1992, mainly because for decades the power to grant water rights was held solely by the Mexican President. The 1992 NWL provided for only one year for all existing users to obtain a concession and be registered, namely by December 1993. The Regulations established that for certain users the said period might be extended for two more years, namely till December 1995. This means that the time constraints were quite stringent, but the NWL vested the authority to grant concessions in the Director General of the NWC and provided for the delegation of certain functions. Since November 1993, even before the Regulations were issued, the authority to grant concessions and wastewater discharge permits has been delegated to the Sub-director General for Water Administration, the regional and the state managers. Also, in order to increase ownership of the new approach and hasten registration, immediately after the law was adopted NWC personnel was trained.

1.21 By mid-1994 it was clear that the target to regularize all existing users would not be met. Application and decision procedures were simplified. For instance, the Director General of the NWC instructed that no additional requirements to those prescribed in the Regulations should be imposed on any applicant. But this was not enough and by October 1995, the President of Mexico issued three decrees for:

· agriculture and livestock;The main benefits provided for by the decrees were:

· industries and services (i.e. businesses, hotels, sports clubs, markets etc.); and

· water supply utilities.

· partial or total pardoning of unpaid charges; and1.22 The Law on National Waters provides for concessions to last from 5 to 50 years. However, the Presidential decrees established that all users who applied would be granted a ten-year concession. The rationale was that in a ten-year period knowledge of water availability and use would be improved and that when users applied for the renewal of their concessions better decisions would be made. Users were given incentives in the form of benefits gained if they adhered promptly to the presidential decrees. The result was that in the year following the adoption of these decrees so many users applied for the benefits of the decrees that the capacity of the NWC turned out to be insufficient to handle all the requests received.

· not applying sanctions for the abstraction of water without a concession or for disposing of wastewater without a permit.

1.23 Although the first set of decrees was well received it imposed bureaucratic burdens both on the user and on the Commission. For this reason and the fact that the additional one-year granted by the first decrees proved again to be insufficient, a second set of decrees was issued a year later by the Federal Executive. These were based on even simpler procedures and, more importantly, trusted the user and limited the discretion of the water authority. Both sets of decrees are compared in Box 1.3 and in the following bullets.

Box 1.3 - Presidential Decrees

|

|

First set of decrees |

Second set of decrees |

|

Users with permit |

Preference in subsidies and other benefits |

|

|

Administrative regularization |

Obtain concession |

Comply with application requirements |

|

Volume |

· Availability and

3rd party effects |

· Declared under oath. |

|

Duration |

5 to 50 years |

10 years |

|

Wastewater quality improvement |

· Treatment plant |

· Treatment plant or

process |

|

Fiscal benefits |

Condoning of partial or total debt |

|

|

Fiscal regularization |

Pay charges since January 1995 |

|

· Only those users using water before October 1995 can apply for the benefits granted by the decrees.1.24 A vigorous information campaign was launched in 1993. Later on, the campaign was intensified and also hundreds of meeting were held all over the country in order to induce water users to regularize their administrative and fiscal situation by applying for the benefits of the decrees. Box 1.4 shows a summary of the brochures and press advertisements that were produced, and Boxes 1.5 and 1.6 show two samples.· More benefits and time to apply for them are granted to domestic and irrigation uses than to industry.

· Responsible users who had concessions and permits before will have preference in terms of subsidies and other support programs.

· According to the first set of decrees, a user was considered regularized only after the Commission issued the concession or permit, whereas the second set of decrees required only that the user comply with the application requirements.

· According to the first set of decrees, the Commission established the authorized volume and duration of the concession or permit through water balances after the applicant demonstrated effective use. However, it was difficult to compute water balances so long as not all uses were known in a particular catchment and the Commission did not have enough staff to carry out the task of verifying in the field that every use was in fact a beneficial one. The second set of decrees provided that in all cases the NWC must issue concessions for 10 years and that the user must declare, under oath, the volumes being used and the volumes sought in the future. The NWC is then required to verify the truthfulness of a user’s claim by checking a statistically representative sample.

· According to the first set of decrees, in order to obtain a wastewater discharge permit and the benefits of the decree, the applicant’s treatment project should be approved by the NWC. The second set required only the applicant to present a simplified program to comply with the effluent standard, and the same applicant was allowed to improve the quality of the wastewater either by building a treatment plant or by modifying the industrial process. The NWC monitors the progress in wastewater quality improvement programs and users that do not progress according to their submitted programs will not receive the benefits of the decrees.

· Penal sanctions are imposed on users who are not truthful in their declarations and their water abstraction titles may be canceled.

1.25 It must be noted that the first set of decrees expired in October 1996 and the second in June 1997 for industry and in December 1998 for other users.

Box 1.4 - Brochures and Press Advertisements to Promote Regularization

|

STAGE |

DOCUMENT |

|

Promotion during |

1. WATER REGISTERED, IS WATER SECURED 2. FLUSH YOUR WASTEWATER/DOWN THE PROPER DRAIN/AND STAY WITHIN THE LAW 3. HERE’S A FAIR DEAL 4. Land and water go together/You need water in this

weather/REGISTER YOUR WATER RIGHT/And you won’t have to fight. |

|

Promotion of first set of decrees |

5. BY REGISTERING YOUR WATER USE/YOU WILL REAP THE BENEFITS. 6. Why throw your benefits down the well?/REGISTER YOUR

WATER/And see how your profits swell. |

|

Promotion of second set of decrees |

7. REQUIRED DOCUMENTS FOR THE REGISTRATION OF SURFACE AND GROUNDWATER USES, ACCORDING TO THE FACILITIES OFFERED IN THE PRESIDENTIAL DECREES. 8. WHERE DOES YOUR WASTEWATER GO?/JUST FOLLOW THESE SIMPLE STEPS/OUTLINED BELOW/AND YOU WILL BENEFIT/MUCH MORE THAN YOU KNOW. 9. DON’T FLUSH YOUR RIGHTS/DOWN THE DRAIN/REGISTER YOUR RIGHT/AND GAIN 10. WE’RE WORKING TOGETHER/TO BUILD A BETTER/ADMINISTRATION/SYSTEM 11. WE’RE IN/EXTRA TIME/BUT OUR PLAN WILL ONLY WIN/WHEN YOUR REGISTRATION’S IN! 12. FARMER..../WATER IS YOUR PRIME RESOURCE,/REGISTER IT/AND

YOU WILL BENEFIT/OF COURSE! |

Box 1.5 - Sample of Press Advertisement to Promote Water Uses Regularization

|

Land and water go together Would you buy land without a title deed? Of course not!. Well, the same applies to water. Did you know that by registering your water usage in the Water Rights Public Register your right to use national water is negotiable, transferable and can even be used as a guarantee to back up loans and financial transactions? Are you sure that your water rights are yours? Prevent anyone else from registering your water usage. Remember that water registration is like the deeds to your land, the Water Rights Public Register is the only way to prove your lawful ownership. REGISTER YOUR RIGHTS TODAY WATER REGISTERED IS WATER SECURED THE NATIONAL WATER COMMISSION |

Box 1.6 - Sample of Press Advertisement to Promote Wastewater Discharge Regularization

|

FLUSH YOUR WASTEWATER DOWN THE PROPER DRAIN AND STAY WITHIN THE LAW Don’t loose any sleep, just do the right thing. If you discharge wastewater in streams, rivers, lakes and sea water or if your wastewater discharge percolates into land, you must obtain a discharge permit. Register your wastewater discharge now in the National Water Rights Public Register. If you don’t you are breaking the National Water Law. The good news is that if you have built or are planning to build wastewater treatment plants to improve your water quality control system, just by registering you will be eligible for special benefits. Preserving the quality of our water is the responsibility of all of us. OBTAIN YOUR WASTEWATER PERMIT TODAY BY VISITING YOUR LOCAL NATIONAL WATER COMMISSION OFFICE We all have the right to good water help us by staying on the right track THE NATIONAL WATER COMMISSION |

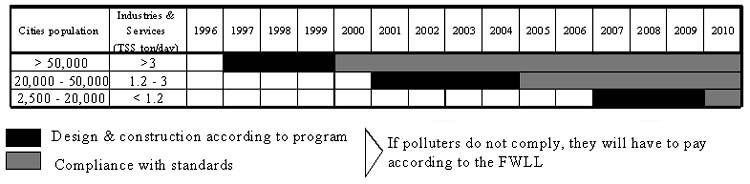

Figure 1.3 - Concession Titles for the Abstraction of National Waters Registered in the WRPR

1.27 Regarding the control of wastewater discharges, probably the most important recent achievement is the adoption in 1996 of a single new standard for all industrial and municipal wastewater disposals. This standard, which is described in Box 1.7, replaced 44 obsolete standards that used to regulate municipal wastewater disposal and different industrial activities. Moreover, Congress has approved reforms to the FWLL regarding wastewater disposal permits, which are consistent with the new standard, that is, users whose disposal does not comply with the standard have to pay the corresponding charge, according to the polluting load. A substantial number of new wastewater discharge permits have been issued under the standard now in force.

Box 1.7 - 1996 Wastewater Effluent Standard

Parameters:- Basic: Temperature, pH, oil and grease, floating solids, settleable solids, TSS, BOD, Total P, Total N

- Heavy metals: (As, Cd, Cu, Cr, Hg, Ni, Pb, Zn) and Cyanids

- Pathogenes: Bacteria, viruses, fecal coliforms and helmynth eggs

|

Users will have to comply only with the limit values

established for those pollutants they produce. The new standard takes into

account both the use of the receiving water body as well as its vulnerability.

It incorporates gradualism, by stating that major polluters must comply in the

year 2000, intermediate ones in 2005 and minor ones in 2010. However, existing

plants must continue operating according to their original discharge permits or

to the new standards, depending on the user’s will. In case the quality of

the discharge exceeds the new standard, the user can apply for a rebate to be

applied to the water abstraction charge. Polluters who exceed more than five

times the limit values set for any of the parameters of the new standard, had to

present one year after the standards were adopted, a design and construction

program to improve their wastewater quality. The rest of them, have to present a

similar program several years before their target compliance date (for instance,

according to the schedule shown above, a medium-size city or industry would have

to present its program by December 2000 and start complying with the standard by

January 2005). Those users who present their programs on time are exempted from

paying discharge charges during the construction period if they progress

according to their programs. |

6 April 29, 1999, Siempre!, page 90, “NWC’s Commitment: The Water Rights Public Register”. During a recent visit to the State of Nayarit, President Ernesto Zedillo was informed by the NWC’s Director General, that according to presidential instructions, by the beginning of the year 2000 regularization of existing users will be completed Therefore the Water Rights Public Register will have been completed and all water users will have legal security in their rights.

1.29 One of the most important economic instruments for water rights administration is the collection of water charges. Charging was introduced in Mexico when the NWC was established with a dual purpose: (a) to promote a gradual shift in water use to higher value priorities and to deter water pollution, and (b) to provide funds for water resources management and development. Fig 1.4 shows the amount of revenues from the collection of water charges from 1989 to 1998 in Mexican pesos.

Figure 1.4 - Collection of Water Charges in Mexican Pesos between 1989-1998

(In 1999 one Mexican peso was approximately equivalent to US$0.10)1.30 The yearly income is represented on the horizontal axis as a percentage of the Commission’s annual expenditure. In Table 1.2 the distribution of income from collection of water charges is shown for the year 1996. Here it can be clearly seen that the income from agricultural/irrigation activities and municipal water supply are negligible compared to those obtained from industrial activities. In spite of the fact that 80 percent of all water currently used in Mexico is for agricultural purposes the agricultural sector is exempt from charges. Hence it can be argued that industrial water users are subsidizing agriculture and municipal users.

Table 1.2 - Income Sources as a Percentage of Total NWC Income during 1996

|

|

Water abstraction |

Waste-water discharge |

O & M |

Others |

|

Industry & Services |

44 |

3 |

|

|

|

Water supply |

6 |

|

18 |

|

|

Hydro & Thermopower |

13 |

|

|

|

|

Irrigation |

Exempted |

|

4 |

|

|

Recovery of arrears |

2 |

4 |

|

|

|

Miscellaneous |

|

|

|

6 |

1.32 The economic ideal would be to remove cross subsidies, however the NWC needs the money it receives from industry. Plus, most municipal water utilities are financially broke and farmers have high social and political standing. Nevertheless, cross subsidies are being removed, but at a very slow pace.

1.33 One of the benefits associated with the application of charging for water is that it has actually encouraged water savings in industry and a more rational geographical allocation of water demanding activities. Also the threat to charge polluters who do not comply with wastewater discharge standards has motivated the construction of many treatment plants. There is also an added incentive to building treatment plants, which is that industries and municipalities which do so are exempted - during the construction period - from paying wastewater disposal charges.

1.34 In conclusion, in spite of some theoretical drawbacks there are some clear benefits associated with the Mexican water charges system:

· Even though the system is not theoretically perfect, it works. In fact, the revenue from charges is substantial (In 1993, 92% of the Commission’s expenditure was covered.); and· Water abstraction charges have induced water savings and more rational allocation, and wastewater discharge charges have induced the construction of numerous treatment plants.

1.35 There are several aspects of the 1992 NWL which address this issue:

· users are free to trade their rights within irrigation districts, with no intervention of the Commission;1.36 In Box 1.8, a summary of water rights trading in Mexico is given.· in the following cases users are also free to transfer their rights, although all transactions must be registered;

* when only the user changes; and· all other transactions are subject to approval in order to protect the environment and third parties.

* in areas designated by the Director General of the Commission.

Box 1.8 - Water Rights Trades in Mexico

|

|

Record in WRPR |

|

|

Without NWC intervention |

Require N\W approval |

|

|

· within irrigation

districts. |

· only user changes |

· other transactions |

|

|

573 groundwater |

|

1.38 The interactions shown on Figure 1.2 are described here in order to illustrate the information required by various procedures of the water rights administration system.

· The process starts with a person applying for an abstraction concession or a wastewater discharge permit.7 The application, with required information and documents is usually presented in any of the 32 state agencies of the NWC. Depending on the required abstraction volume and the relative water scarcity, the state manager will decide or prepare an opinion and transmit it either to the corresponding regional manager (there are 13 in the country) or to central offices. If there is not enough water or another competing application is judged more beneficial to the public interest, the application is denied. If it is approved, the corresponding title is issued, recorded in the WRPR and handed to the applicant.1.39 Given the number of users, the complexity of factors which have to be taken into account to issue a concession or a permit and to monitor compliance, as well as the need to follow up progress at the national, regional and state levels, the information management needs are quite large and dynamic. Since 1993, after the National Water Law was enacted, four main data bases have been developed:7 Only the procedure regarding abstractions is described for illustrative purposes.· All relevant documents, regardless of whether the decision was favorable or not, must be properly filed and safeguarded for future consultation. The process involves several stages and the participation of different offices and it is necessary to keep track of time because the Commission has to respond within a maximum of 90 working days after the applicant has provided all required documents. A title is the legal proof of a user’s water rights, so its record must be kept in the WRPR as well as any changes in the status such as expiration or changes due to rights trading.· Users have to comply with the terms and conditions of their concession titles and wastewater discharge permits, and make quarterly statements of the charges to be paid according to the abstracted volume and the polluting load of the wastewater discharge. They fill out payment forms and pay at designated banks. Monitoring is carried out by the NWC with a sampling approach to verify if users are complying with the terms and conditions of their titles and permits and if they have paid the correct amount of charges. Records are kept for statistical and legal purposes. The NWC has the power to penalize users who do not comply and illegal users who are detected by the Commission.

· If the user is in disagreement either with the decision on his application or the sanctions imposed by the Commission, she or he can lodge an appeal to the Commission itself or to the courts of law. A close follow-up of each appeal is mandated by the law.

· Users’ population. This is a “learning model” which estimates the number of users and polluters as well as abstraction and wastewater discharge volumes, through available hard data and indirect information and indices. The model is gradually improved by feedback as monitoring progresses and provides more hard and reliable data.1.40 The business procedures related to water rights administration are quite straightforward and accordingly it should be easy to design a computer system dealing with all its components and the interface among them. However there are different kinds of factors (hydrological, ecological, economic, social, political and organizational) which determine how and at what pace actual implementation in the field can be achieved. These factors usually shape the business procedures and in turn impose restrictions on the information systems (hardware and software) which can be used. Accordingly, the four databases were independently developed and each has been improved according to the field experience in each case. Consequently, the resulting subsystems are not as dynamic and conversant as desirable. The following improvements are being carried out:· Applications follow up. Keeps track of all steps required to reply to a user’s application.

· WRPR data base. Keeps files of concessions, permits and water rights trades. Provides information to the public on request.

· Water tax payers. Keeps track of charges paid by users and polluters.

· procedures are being simplified to improve the services to the applicant and water user;1.41 The Mexican experience has made it clear that the desirable attributes of a water rights information system are those shown in Box 1.9.· auditing and training are improving quality control of data, processes and decisions;

· desirable improvements for software and hardware as well as telecommunications have been identified, taking into account the best available technology, but it has been recognized they must be gradually introduced and cautiously implemented; and

· an executive module with relevant summaries is being developed to aid decision-makers.

Box 1.9 - Desirable Attributes of a Water Rights Information System

|

· The system must be “problem-oriented”, not “technology-oriented”. The amount of information, the usual complexity of the factors involved and their inter-relatedness justifies the use of the best available information technology in water rights administration. But it is advisable to develop the system on a gradual basis. The first stage should use information technology as simple as possible in order to put in place the complete water rights administration system as soon as possible. Only after all intricacies of water rights administration have been understood and procedures tested in the field, should more sophisticated technology be introduced. · The implementation stages to improve information technology should take into account * available trained human resources as well as existing software, hardware and telecommunications networks; andThis analysis allows to establish a capacity building program to create the required enabling environment for improvements in information technology. · The system must contain reliable information. This means that auditing must be established to ensure different levels of reliability: * digital data reflects accurately information from documents;· Protocols for updating information must be strictly followed, otherwise the information system rapidly becomes obsolete · The system must be “user-friendly”. · The system must be tailored to fit the requirements of decision makers at all levels of the institution. · Particular attention should be given to: * feeding the processed information to those persons who supply the raw data. (Sharing with data-providers the analyses carried out with their data motivates them to continue providing data); and |

1.42 From the account given above of Mexico’s water rights administration, it can be seen that great progress has already been made in this area. There is now in existence an organized system of procedures, which has been made available to personnel. The procedural system canvasses the following operations:

· reception of applications for water abstraction and use;1.43 There is also a structured information system for keeping track of the data involved in the above procedures. All components have been made available at national, regional and state levels and personnel has also been exposed to a first stage of training. In order to ensure that the program develops as a well-conceived sequence of steps, some of its components are being improved and their interactions assessed.

· reception of applications for wastewater discharge;

· processing of applications;

· registration of titles in the Water Rights Public Register

· in situ verification of compliance with the law; and

· verification of payment of water charges.

1.44 Now, it is important to continually keep track of how the system is operating and to ascertain that the proposed goals are being met. It is essential to evaluate the effectiveness of this system where it counts, when applied in the field. The Sub-directorate General for Water Administration (SGAA) continually carries out visits to state and regional areas in order to assess the situation.

1.45 The reasons for these visits are as follows:

· to confirm that information supplied by regional management is consistent with that handled in the central offices, to ensure coherence between the different components of the information system; and1.46 A sample of the subsequent reports prepared by the SGAA by mid 1998 is summarized in Box 1.10. As a result of this survey it became evident that there are still some problems in the implementation of the water rights administration, which need to be solved. This is probably due to the fact that the resources available to carry out the task in hand may be less than needed. The following reflects the lack of resources:· to check the correct application of the mandates, guidelines and prevailing procedures, as well as to identify difficulties which may be encountered by regional and state management in the updating of administrative and fiscal records concerning water users.

· After each visit the central and regional officials establish commitments with deadlines set, to solve the detected problems. However, the heavy work load in the central, regional and state offices and the lack of human resources have made it extremely difficult to provide the required follow up and to meet agreed deadlines.· Based on this experience it is possible to design a better system of supervision and follow up with an appropriate training program. However, for this to succeed it is essential to have all the necessary resources.

Box 1.10 - Summary of Problems and Solutions in the Implementation of the Water Rights Administration System.

|

Areas for improvement |

Problems |

Solutions |

|

Promotion |

During the launching of the implementation of the Presidential

Decrees massive communication programs helped to attract a large number of

applicants. Present promotion actions are less intensive. |

Contract the company which designed the first campaigns or

contract a new company to assist in keeping up the communication flow. |

|

Users’ viewpoint |

Although service is friendly, users claim to be dissatisfied due to: · incompetent personnel; and |

Determine if there is a need to reorganize at the state,

regional and central level, to train personnel or both to increase user

satisfaction. |

|

Follow up system for user applications |

A small number of applications have been processed. |

Determine if the present system is too complicated and

difficult for personnel to apply, or if it is a lack of human resources

problem. |

|

Registration in the Water Rights Public

Registry |

· Flow of documents is too

slow. |

Implement total quality focus. |

|

Collection of water charges |

· Little interaction between the Water Administration and the Fiscal Administration. · Badly organized files. · Available resources are not

fully exploited. |

· Establish adequate

procedures. |

|

Inspection and control visits |

· Declared volumes differ from those officially allowed. · Deficiencies in the carrying out of visits and in the filing of relevant reports. · Non systematic sealing of measuring devices. · Errors in the application of

sanctions. |

· Establish adequate

procedures. |

|

Norms, guidelines and formats |

Non systematic distribution and application of

guidelines. |

Focus on overall quality of the regional, state and central

offices |

|

Handling of files |

Unorganized and defective application of the norms. |

Implement total quality focus. |

|

Information Systems |

· Inconsistency between

different systems. |

Speed up the implementation of the integrated information

system designed in 1997 while at the same time make full use of the existing

system. |

|

Available resources |

Serious limitations in human resources, material and financial

resources. |

Increase resources or decrease goals and simplify procedures

to fit the available resources. |

|

Reorganization |

Lack of definition and familiarity with the new organization

and its geographical coverage. |

Define and make widely available at all levels of the

NWC. |

· The procedures could be critically reviewed, in order to further simplify them and to assure internal consistency; and1.48 Regarding the information system, by mid 1999 it appeared that it would probably be wiser that the group responsible for this system stopped any new development and concentrated its efforts on assuring that: personnel really use and take advantage of the existing system; personnel are adequately trained; personnel have all the necessary hardware and software; and, apparently trivial details, whose lack seriously hinders implementation, are taken into consideration such as the provision of power back-up systems, the timely supply of stationery, and the availability of adequate computer furniture.· A total quality focus could be applied and quantitative follow-up parameters determined, so that it will be possible to:

* measure users’ satisfaction with the system;* estimate efficiency, by answering questions such as, “is water being more efficiently used and more rationally allocated?”; and

* estimate effectiveness by answering questions such as, “are the procedures applied correctly and in a timely fashion?”.

1.49 The following observations to improve the results of monitoring visits, based on the analysis of Box 1.10 can be made:

· the organization of the inquiries carried out during the regional and state visits needs to be more structured, with a greater adherence to the framework outlined in the procedures and in the information systems currently in place;1.50 Actions to correct the problems identified above are being taken. Also, by using the suggested systematized approach, it is expected that future implementation problems encountered in the monitoring visits will be easier to detect and will simplify corrective actions. Furthermore, recent news in the press show that water rights administration has to deal also with criminal offences;8 therefore, monitoring and enforcement systems have to be continually reviewed in order to improve them.· reports should be more analytical as well as provide problem definition and suggest a solution; and

· in order to avoid unexpected answers which may be difficult to systematize, a multiple choice format should be used, rather than basing reports on open ended questions.

8 May 13, 1999, El Heraldo, page 2. “False Water Titles are Identified in El Bajio. The NWC informed it has detected that water titles have been forged in several cities of the Bajio region. The Commission said it has already presented the cases before penal authorities. It also recommended water users who have bought water rights to go the Commission offices and verify the corresponding entitlements are authentic ones. All application formalities to obtain a water concession or register a water rights transaction should be carried out at the Commission’s agencies in its regional and state agencies. There is no need to rely on so-called stockbrokers”.

1.51 It is important to recognize that the setting up of a sustainable water resource management system is not an overnight process. One of the main reasons is that putting in place an effective and efficient water rights administration system, which at the same time satisfies the user, is a very complex and lengthy process. Consequently, just setting the stage for such a water resource management system in Mexico has been reckoned to take in the region of 15 years. A possible 15 year workplan, as outlined in Box 1.11, was recommended by the author in 1997, when he still worked as the National Water Commission’s Deputy Director General for Water Rights Administration.

Box 1.11 - A 15-Year Implementation Program

|

1. Regularization of water abstractions. Following the presidential decrees, it is expected that most of the estimated existing users will have applied for their permits by December 1998, and during 1999 all will have been regularized, most of them through permits with a duration of 10 years. 2. Regularization of wastewater discharge permits. By the same token, most waste water discharges will be known and their respective permits issued by the end of 1999. 3. Implementation of river basin councils and groundwater technical committees in problematic areas. Actions are presently being taken in order to establish councils and committees in such a way that they genuinely represent users and stakeholders in each water stressed area. 4. Improvement of water availability and water quality data bases. In 1995 a program partially financed by the World Bank was started. Its mission was to modernize the following: · Meteorological, hydrological, groundwater and water quality data;This information will be very valuable, as it will provide more reliable inputs which will back up river basin and aquifer models. This will especially be true when the 10 year permits expire, and it becomes necessary to assess both applications for new permits and the renewal of existing permits to abstract water and to discharge wastewater. 5. Improvement of legal and fiscal frameworks. Continuous feedback from implementation will provide inputs to improve legislation. 6. Implementation of a code for water regulation and use. Once existing uses are known, respective rights registered and better information on water availability and quality becomes available, it should be possible to communicate to users and stakeholders, in problematic areas, the consequences of continued water abstraction and pollution. It is expected that by then the river basin councils and groundwater committees will be operational and willing to establish self-enforcing regulations that will address the following: * the restoration of the hydrologic equilibrium in aquifers;7. Substantial increase in wastewater treatment. This activity is expected to be accomplished by 2010 which is when the smaller controlled users will have to comply with the new wastewater discharge standard. 8. Law enforcement through intensive monitoring of water abstraction and wastewater discharges. This is probably the most difficult task of all. Now that the presidential decrees have expired, the NWC will have to convey the message to society that the water authority is in fact exercising the power vested in it by the Constitution and the laws. This will be achieved, by sampling representative users and polluters in the field, and applying severe penalties to those not complying with the conditions of the said decrees or of their respective permits. Intensive and well organized actions such as these will in fact increase the credibility of the Commission. But this will not be enough. These regulatory actions will have to be complemented by economic and participatory measures. Regarding the economic measures, firstly the fiscal framework will have to be improved in order to get water charges more aligned with sound economic theory. Secondly, once the knowledge of water availability and existing uses is improved, it will be feasible and desirable to promote water rights trading. 9. Capacity building with “user-oriented”

approach. Besides improved planning, and a better legal framework, there is

a need to achieve a truly enabling working environment and to keep up and

increase in quantity and quality human resources training, education and public

communication, for the whole water sector’s public and private

organizations. A new focus is needed, one which has as its ultimate goal to

satisfy not only the water needs and expectations of high quality service of

present users, but also those of all water users of the next generations.

1.18. |

1.52 Mexico’s experience offers the following pointers of general validity to the design and operation of water rights administration systems:

· Adjustment as a result of trial and error is a legitimate feature. Mexico has substantially progressed in the implementation of its Water Rights Administration System. Neither the organizational structure nor the water legislation that support such system is perfect because it is impossible to anticipate every conceivable implementation issue. Some flaws have been identified through practice and have been dealt with in a dynamic fashion adjusting gradually the organizational and legal frameworks. The lessons gained in this process may be of benefit to other countries that could be in a position to anticipate implementation issues while drafting their water legislation, regulations and implementation tools.· A balance needs to be struck between the administrative and the ecological boundaries and requirements of the water rights administration. The NWC originally set up 33 state agencies and 6 regional agencies that grouped states. Recently the number of regional agencies was increased to 13, whose boundaries follow water divides as closely as possible. This boundary re-definition is consistent with the widely accepted international principle of river basin planning and management, which has been incorporated in the Mexican water legislation. However there are now several states that in order to address their water issues have to deal with more than one river basin agency. The following challenges will have to be faced in order to make the principle operational: (a) developing technical and managerial capacity for the increased number of agencies, (b) modifying procedures and information systems (technical and managerial) in order to fit the new territorial organization, (b) establishing an adequate communication and negotiation strategy and mechanisms between the NWC and state Governments.

· The legal obstacles borne out by practice and experience need to be removed. The following legal and administrative provisions have been introduced between 1995 and 1998 in order to remove some obstacles that hindered implementation:

* Both the NWL and its Regulations came into force all over the country the next day they were published in the Gazette. Therefore it was necessary to prepare guidelines, procedures, forms and manuals in parallel with implementation.· A fruitful and dynamic bureaucratic-political relationship needs to be built and nurtured. The “ideal” situation (perfect water legislation, perfect organizational structure, enough human-economic-material resources) required for a water rights administration system could neither be conceived or obtained from the outset. What is required is that those in charge of operating the system make a convincing case for their requirements to be met. But this is not enough; it is also required that the decision-makers and politicians respond sensibly and support the practitioners. This has happened in Mexico. For instance, political support at the highest level has been evident through several presidential decrees that have helped to implement the system. Another example is the fact that after the overflow of applications from existing users, the Director General provided resources (new staff, computers and vehicles) to deal with the increased workload.* The time prescribed by the NWL and its Regulations to regularize existing uses and wastewater discharges was too short. Therefore a set of presidential decrees extended the regularization periods, simplified the requirements for applicants and pardoned unpaid water charges.

* Good cause for not canceling unused concessions was provided by a presidential decree.

* Areas where water rights could be transferred separate from land property were prescribed through a presidential decree and a notice in the Gazette from the NWC Director General.

· Communication plays a critical role in achieving success in the registration of existing users. Besides the presidential decrees, a vigorous media campaign and direct relationship with water users through meetings with individuals and their representatives have played an important role.

· Functional integration needs to be pursued. Both administrative (issuing of concession titles and wastewater discharge permits) and fiscal (water charges collection) functions fall under the same organizational unit. This has been an asset, because a consistent approach has been developed in the relationship with the NWC’s customers in their roles as water users, polluters and tax-payers. One drawback is that technical functions are carried out by a different unit, which is also in charge of many other tasks such as water quantity and quality monitoring, water resources assessments, the National Weather Service and dam operation. Therefore, because of its own agenda and priorities, it is difficult for the technical group to provide, within the required time frame, the specific water resources quantity and quality assessments and other inputs required to decide on each application for a water concession or wastewater discharge permit. This could be overcome by including in the water administration group some minimum technical expertise and charge it with full responsibility in deciding on applications.

· The economic value of water needs to be recognized despite practical difficulties to imple-ment economic theory. In fact, despite cross subsidies from industry to water supply sys-tems and the fact that irrigation is not charged, the revenue from the collection of charges has been substantial (in 1993, it covered 92% of the Commission’s expenditure). Also, water abstraction charges have induced water savings and more rational allocation, and wastewater disposal charges have induced the construction of numerous treatment plants

· The useful role of water markets should be accepted. Water markets in Mexico may play a significant role in future. Most existing water users have been registered and water quanti-ty and quality databases are being improved. If this trend continues, water markets may be playing an important role in water resources reallocation by the end of the next decade.

· Information systems can be a worthy support for water rights administration, provided they are kept simple and improved gradually.

· Monitoring of performance is to be reckoned with as the most difficult, yet critical, task of water rights implementation. Without carrying out this task, law enforcement cannot be achieved. However, it is probably the activity most dependent on proper capacity building. The NWC has started it through periodical visits to water users in the field and is permanently improving its monitoring procedures.

· Setting up a water rights administration system, which plays a central role in the sustainable management of water resources, must be regarded as a lengthy process. In this paper a 15-year implementation workplan has been suggested. As a result, the time frame for achieving sustainable water resources management cannot be measured in months, but in decades.

Garduño, H. “Information Needs for Water Rights Establishment in Mexico”, (Presentation at the Expert Consultation on Integrated Land and Water Information Systems), FAO, Rome, 1997a

Garduño, H. “Water Rights Implementation”. (Presentation at the First Regional Seminar on Policy Reform in Water Resources Management. MENA/MED Water Initiative, Cairo, Egypt), 1997b

Garduño, H. “Modernization of Water Legislation: The Mexican Experience”, Issues in Water Law Reform, Proceedings of the Expert Consultation, Pretoria, South Africa 3-5 June 1997, FAO, M54, ISBN 92-5-104252-7, 1999

Jiménez, B.E.; Garduño, H. and Domínguez, R. “Water Availability in Mexico Considering Quality, Quality and Uses”. Journal of Water Resources Planning and Management, American Society of Civil Engineers, Jan-Feb, 1998