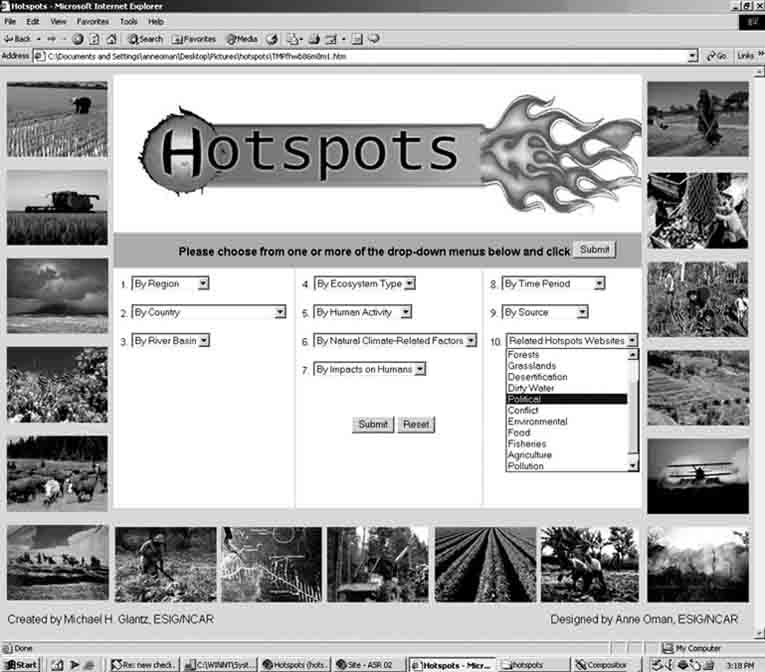

AS A MAJOR CONTRIBUTION TO A HOTSPOTS INITIATIVE, SDRN COULD UNDERTAKE WHAT COULD BE CALLED AN FAO "HOTSPOTS AUDIT". The purposes of such an audit would be twofold. First, to identify hotspots identification and monitoring activities that are currently carried out by various groups within FAO. In fact, a first step toward such an audit was taken when SDRN convened its hotspots workshop in Rome in mid-December 2002. An audit would require a survey of FAO activities that relevant to the agreed definition of hotspots. Second a follow-up, involving undertaking a similar audit (assessment) within other organizations that focus at least some of their activities on hotspots-like detection and monitoring. These organizations include, but are not limited to, the World Bank, the World Resources Institute, Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, Conservation International, International Strategy for Disaster Reduction, World Meteorological Organization, World Health Organization, and NASA. The results of these audits, as well as the definitional context of hotspots, would be placed on the Internet at a special Web site (with URLs like <www.FAOhotspots.org> or <www.hotspotsaudit.org>.

Ease of identification and monitoring of hotspots will probably vary, depending on the type of hotspot. For example, for climate-related hotspots, there is often an identifiable climate catalyst, such as drought, flood, fire, an El Niño or a La Niña event. For Ag-En hotspots, there are unlikely to be obvious thresholds of adverse impact, such as a rapid step-like change in environmental conditions (e.g. how many trees must be cut down before a change is referred to as deforestation?). Instead, one can expect a series of small, incremental (creeping), slow-onset cumulative changes. Nevertheless, for any one of the changes in the impacts at the Ag-En interface, there are sure to be underlying as well as precipitant causes that can be identified. It is most important to identify them early and, if possible, in the AOC stage, before they reach hotspot status.

|

Box 2. Nutritionists are very familiar with hotspots Malnutrition frequently occurs in food insecure areas and reflects breakdown of local livelihoods or their inherent unsustainability. Traditional farming systems - which are still prevalent in many remote areas - were usually fairly complex: they were based on local natural resources and were geared to provide basic needs, ensure community survival and minimize risk. Although clearly not perfect, they focused on local resilience since external assistance was not expected. With economic development, increased external involvement and new expectations, these systems have evolved. Abandonment of traditional farming practices and changes in rules and regulations have in some cases resulted in increased vulnerability to shocks (be they climatic or economic). Poor people are clearly the first and the most affected. They may have had to migrate into forest or mountain areas under population pressure or civil unrest; tenure issues may be an obstacle to environmentally sound agricultural practices; conservation policies and projects limit access to forest resources (for fuelwood, fodder, timber or food); and survival strategies may lead to further environment degradation (e.g. charcoal production). Coping strategies of food insecure (and therefore nutritionally at-risk) people often directly affect the environment: refugees exert an excessive toll on the wood resources; fields and traditional conservation practices are abandoned due to labour constraints (e.g. male migration in search of income, high incidence of disease - such as HIV/AIDS - or disability); cropping patterns undergo changes leading to overexploitation of soil resources. Typically, farmers are forced into growing more marginal land, i.e. land more difficult to work, stony, with low natural fertility or poor water storage capacity. Fallows also become shorter and shorter, thereby degrading the land and preventing the build-up of nutrients between cultivations. Marginal land will also tend to amplify environmental fluctuations (increase rainfall variability) instead of alleviating them, so that even a slight deficit of rainfall can trigger an agricultural or hydrologic drought and initiate the poverty spiral. Decrease in production is clearly reflected in decreased food consumption and limited food diversity, leading to stunting, micronutrient deficiencies and, eventually, wasting, which in turn affects the productive capacity of the household. "Malnutrition hotspots" would include, for example, drought-prone areas of southern Africa and of the Horn of Africa, many mountain areas (Afghanistan, Nepal, etc.), forests in Central America, countries affected by conflict in the Great Lakes area of Central Africa, and many fast expanding cities. It is therefore desirable that a hotspots audit approach involve specialists from both environment and socialrelated disciplines. Florence Egal, FAO Nutrition Programmes Service, ESNP |

A hotspots audit within FAO could be beneficial and serve several purposes at the same time, some of which include: early warning; crisis avoidance; minimizing "surprises;" and advise (or alert) governments, international agencies and NGOs about the increased likelihood of severe environmental degradation that can result from human activities.

The SDRN workshop deliberations in December 2002 in Rome could serve as a preliminary survey of the various activities and units in FAO already engaged in a form of early warning or hotspots-like identification. The groups represented at the workshop included those dealing with fisheries, food insecurity, nutrition, wetlands, forests, mangroves, rangelands, climate change and desertification.

Each organizational unit has its set of discrete functions to perform and objectives to achieve. Given the wide range of concerns, these objectives cannot be met by using only one universal set of indicators. For example, an early warning system for environmental degradation linked to agricultural practices will, to some extent, depend on the type of ecosystem affected and, depending on the ecosystem, will require different but overlapping sets of indicators. Thus, early warnings will vary for food security hotspots, Ag-En hotspots, rangelands hotspots, climaterelated hotspots and nutrition hotspots. Thus, SDRN can develop a broad but usable definition of hotspot, and the other units can develop discrete operational definitions. All hotspots activities, however, could be listed on and linked to a "meta-hotspots" Web site, even though operating independently.

A second audit should be undertaken to identify the actual Ag-En hotspots around the globe in regions of primary concern to SDRN. Other FAO units interested in the hotspots concept could be encouraged to undertake a search for hotspots in their areas of interest. The results of all these audits would be placed on the meta-hotspots Web site.

Considerable research interest has focused on assessments of environmental processes of change, with less attention, relatively speaking, paid to the rates at which many of those changes are taking place. However, one could argue that the rates of change are as important as the processes of change. Fast rates of change tend to stimulate if not accelerate decision-making processes in societal attempts to cope with the impacts of such changes. Slow rates of change, however, tend to be ignored as more urgent issues capture the attention of policy-makers. Ag-En audits would need to be undertaken periodically in order to monitor the rates of changes at the Ag-En interface, as well as monitoring processes (causes and effects) and trends.

The notion of Ag-En hotspots, broadly considered, requires thoughtful definition, even if aspects of the definition appear to be too qualitative to quantitativelyminded individuals. The type(s) of adverse Ag-En interfaces must be identified and prioritized in order to keep the activity manageable. It can become more inclusive as time progresses.

To undertake an Ag-En hotspots activity, it is important to maintain efforts for at least a three- to five-year period, during which the activity should be re-evaluated at a midcourse correction workshop (comparing objectives with achievements). There are several potential hotspots "auditors." For example, in-house FAO personnel, non-FAO personnel such as private consultants, or representatives of an environmental NGO could undertake an audit. It could also be undertaken by a combination of the above, or in cooperation with a yet-to-be-developed network of hotspots observers (e.g. volunteer hotspots monitors). Monitors could be identified in different regions defined as AOCs, as well as within areas already designated as hotspots. The expertise needed by the auditors would depend in part on the indicators and methods chosen for monitoring changes in the hotspots. Because those indicators are likely to be an effective mix of quantitative, qualitative and anecdotal, as well as physical, biological and social, auditor selection will be very important.

In fact, two sets of Ag-En auditors will be needed: the first set of auditors would be responsible for an initial (first-time) audit, and would be guided by the indicators chosen by experts selected by SDRN. Once those indicators have been chosen and the first audit carried out, a second set of auditors (or a consultant alone) would have the responsibility for subsequent audits, undertaken at a proposed two-year interval. The second set of auditors would be responsible for the presentation and publication of results of the audit and the projection of hotspot trends into the near future. These results would appear at first on the Internet, and eventually, as funding permits, as printed reports.

Information and data needs related to monitoring changes in hotspots, or perhaps AOCs, can be derived from existing data sources and time series of many types, inter alia: satellite imagery, NDVI, GIS, production statistics, environmental change indicators (soil erosion, soil moisture, extent and type of vegetative cover, deforestation rates, desertification data), food security and insecurity information, climate and climate-related time series, ENSO time series and forecasts, teleconnections projections for ENSO's warm and cold extremes (El Niño and La Niña, respectively) and historical accounts.

There are many target audiences for the results and outputs of hotspots audits and activities (i.e. the identification, monitoring and reporting system). They include various groups within FAO and in other UN agencies, national policy-makers, researchers, specific government ministries, NGOs, and individuals and groups at the local and regional levels. Because it would be difficult to meet the specific needs and interests of each of such a wide range of potentially interested parties, it is important that those undertaking a hotspots activity identify and prioritize the primary audiences they wish to reach.

An Ag-En hotspots audit could be undertaken at two-year intervals. An audit would include documenting changes that had taken place in the previous biennium and, more importantly, projecting expected changes in the AOCs and hotspots at two-, five- and ten-year intervals. A two-year time interval (or greater) for a review of changes and adjustments to previous projections is considered adequate to capture the level of degradation at the Ag-En interface where hotspots are likely to appear or intensify but are not likely to have changed very rapidly from one year to the next, exceptions notwithstanding. In the two-year interval between successive audits, emergency bulletins in the form of watches, warnings or alerts could be issued if rapid changes were to occur, either for better or for worse. The projections would be based on changes in hotspot conditions under a "business-as-usual" scenario (i.e. based on changes in the physical, biological and societal hotspots indicators used for monitoring). This means that in the event of an absence of political or social responses to the continued degradation of the Ag-En hotspot, the hotspot could worsen to become a hotter or hottest hotspot: a location with severe degradation that sharply affects agricultural productivity and impinges almost irreversibility on the ecological health of the environmental setting.

With growing worldwide demand for food, fibre and cash crops, and with expanding populations in recent decades, an increasing number of locations around the globe have seen agricultural activities and environmental conditions (e.g. land, water, air, ecosystem and human health) interacting in adverse ways (e.g. the Ag-En interface: farm-forest, forestplantation, food vs cash crops, farm-rangeland, etc.).

Depending on the eco-setting and the type of agricultural activity, these interactions can result in, for example, farmers encroaching on forested areas to cultivate new areas, or shrimp farmers carving out shrimp ponds in the mangroves to engage in short-term lucrative shrimp farming, or cultivators converting grazing areas into farms either for food or cash crop production.

In many instances, the movement of human activities has been into areas that are marginal for the those newly introduced agricultural or rangeland activities. When crop failures ensue, governments as well as farmers tend to blame drought, for example. This process has been referred to as "drought follows the plough" and has been described for processes in the United States of America, Africa, northeast Brazil and the Former Soviet Union (Glantz, 1994). Marginal areas can be defined by soil quality, rainfall characteristics, slope of the terrain, water availability and altitude).

To a certain extent, some land-use changes in various types of landscapes can be viewed simply as land transformation; that is, land transformed from one use perceived to be of value by one group, to a different use considered to be valuable by another group, without permanent harm to the environment: rangelands turned into cultivated areas, forested areas into sources of firewood, mangroves into a few small shrimp farms. However, if those transformations in a given locale continue, and certain (usually unanticipated) thresholds of adverse change in the environment are crossed, what was initially viewed as seemingly harmless land transformation has incrementally turned into severe land degradation. These locales can be viewed as Ag-En hotspots, where agricultural practices and environmental conditions interact to cause environmental degradation. If the processes of degradation are allowed to continue, the hotspot will become hotter and, if still left unattended, it could become a region's hottest hotspot. In addition, changes in the productivity of the land are likely to occur as a result of reduced soil fertility or reduced yields.

The creation and evolution of Ag-En hotspots can be identified and observed on the ground, from aircraft, and from space - and even in libraries, with each data source providing unique, as well as overlapping, information. For example, local histories of land, vegetation and land-use changes, based on anecdotal, qualitative and quantitative data, can be used to track the history of land transformation in specific locations of concern, in order to identify when and where the path to hotspots emerged, as well as to provide leads about why they became problematic.

As another example, satellite imagery is used to detect changes in land cover over time, as has been clearly demonstrated in monitoring changes in the Brazilian rainforest in the Amazon basin, as well as with salinization of soils in arid areas, such as in Central Asia's Aral Sea Basin.

Anecdotal information, especially for early warning activities, can often prove to be as important as other types of information that are considered more scientific (e.g. quantitative) and, therefore, perceived to be more objective and reliable. However, stories about how the land and its vegetative cover have changed over time provide rich accounts of underlying, often hidden, factors and changes that might not have been captured by other methods of detection. Novelist Chaim Potok (2001) wrote that "without stories there is nothing. The past is erased without stories" (on the use of analogies and qualitative information for forecasting purposes, see also Glantz, 1991; Jamieson, 1988).

Perceptions of agriculture-related environmental changes do not always reflect reality. Nevertheless, people tend to act in response to their perceptions of reality, not necessarily on objective, quantifiable measures of reality. Their actions will have real consequences for agriculture and the environments affected by their perception-based actions.

A hotspots audit worldwide could help to avoid crisis situations, and it could also serve to monitor existing creeping environmental problems. Creeping environmental problems (CEPs) usually prove to be an environmental change involving both human activities and natural processes, such as soil erosion, deforestation, forest dieback, desertification, mangrove destruction, coastal pollution, soil salinization or waterlogging. It is important to note that no government - rich or poor, industrial or agricultural, capitalist or communist - has as yet dealt effectively and efficiently with CEPs until those problems reached a crisis stage. Land degradation resulting from human activities is often a slow, low-grade, incremental but cumulative adverse change. In fact, most environmental changes in which human activities have been implicated have been of this creeping kind. If left unaddressed, such incremental, cumulative creeping changes often turn into CEPs (Glantz, 1994, 1999). Today's CEPs are likely to become tomorrow's environmental crises.

For some ecosystems, there may already be readily identifiable thresholds of change, when, for example, one type of vegetation is seen to invade an area previously occupied by another type. Unfortunately, for many ecosystems, those thresholds usually become visible only after they have been transgressed. This suggests that thresholds of environmental changes (transformation and degradation) need to be subjectively determined by concerned observers for purposes of monitoring as well as for pro-action (prevention or mitigation).

Political interest in land transformation, degraded areas of concern, hotspots and flashpoints generally centres on a desire for early warning. Every government wants to know as early as possible about impending changes that can impinge, usually in a negative way, on the routine processes of government, normal politics and societal well-being. A focus on hotspots is a focus on a transition zone where societal mitigative or preventive actions are needed, if continued degradation of the environment and the eventual degradation of the land's productive resources are to be avoided.

Government agencies, departments or ministries, each with their different bureaucratic jurisdictions, are interested in the earliest credible warning of potential problems they may have to face in their areas of responsibility. Thus, they are interested in identifying as far in advance as possible the factors that might add to cultural, environmental or governmental instability.

Nature-induced hotspots can, for example, be caused by naturally occurring volcanic eruptions or by El Niño events. Societally generated instability related to hotspots can be caused by ethnic conflicts, transboundary political differences over ownership of land or water, religious differences, and so forth. The causes for the emergence or continued degradation of climate and climate-related hotspots, for example, could be drought, flood, fire, frost, severe storms and the like. Ag-En hotspots, as noted earlier, occur when agricultural activities and the environmental setting in which they take place interact in a potentially adverse way.

Identifying the parameters of and value for the "earliest warning possible" of the likely emergence or worsening of an Ag-En hotspot falls under the purview of FAO. Hotspots, if left unattended, become hotter spots and can lead to any one or a combination of a range of impacts such as: a reduction in food production, a loss of soil productivity, food shortages, deforestation and environmental and societal problems related to desertification. Even if a government is not in a position to take action using its own limited resources to slow down or arrest the degradation of the Ag-En hotspot, it will have been at the least forewarned. This would allow the government enough lead-time to seek assistance from other countries.

|

Box 3. Nutrient overload hotspots in Asia

Overfertilization of crops, overfeeding of fish in ponds, improper management of agricultural and industrial wastes and other forms of mismanagement often result in nutrient overloads. Their major effects include surface water pollution with low oxygen contents and resulting mortality of aquatic organisms, threatening aquatic ecosystems and the quality of water for further uses, deterioration of the quality of groundwater, accumulation of nutrients and pollutants in the soil, and impact on natural areas such as wetlands, often leading to biodiversity losses. The map above shows balances of phosphate on agricultural land, calculated on the basis of livestock densities, crop uptake, and chemical fertilizer use. If the balance is positive (red), there is an environmental risk due to oversupply of nutrients; large negative balances (green) point to a risk of nutrient depletion. Average values (light green to ochre) indicate that there is a potential equilibrium in the crop-livestock and crop-fertilizer-nutrient situation. Nutrient overloads are found in north-east India, east China, coastal areas of Viet Nam, Java (Indonesia), central and north Thailand, with especially high surpluses at the margins of urban centres, such as Bangkok, Ho Chi Minh City and Manila. It is estimated that about 25 percent of the agricultural land in the study area is subject to phosphorus oxide surpluses, while 15 percent suffers high surpluses (more than 20 kg P2O5/ha agricultural land). Livestock is the dominant source of nutrient around urban centres and in livestock-specialized areas (southern and north-eastern China), while chemical fertilizers are dominant in crop (rice) intensive areas. Pierre Gerber, Pius Chilonda and Gianluca Franceschini (FAO Livestock Environment and Development Initiative) and Harald Menzi (Swiss college of Agriculture, Zollikofen) |

The hotspots auditors should collect information and views about real and perceived hotspots from various individuals and from reports (published and unpublished), noting the definitions of hotspots and the indicators used to identify them. FAO could then select the set of indicators appropriate to its concerns in order to make its own selection of hotspots to be monitored and highlighted. Alternatively, it could collect from various organizations all of the identified hotspots, including those mentioned earlier, describe them and discuss the indicators that had been used to identify them.

The various factors involved in the creation and evolution of the hotspots of concern can then be analysed. The auditors would then project the likely progression of the hotspot over time. The likelihood (i.e. foreseeability) of a reversal or slowing down of the underlying processes that generate or maintain the hotspot can be assessed.

The auditors can use this information to search for, using analogues, "present-day futures" (e.g., present futures). Present futures refers to a belief that somewhere on the globe one can find a situation of degradation that closely resembles what the Ag-En hotspot of concern would most likely become, under a "land-use-as-usual" scenario.

As an operationalized notion, present futures underscores the belief that many processes of land degradation as a result of agricultural activities are neither new nor unique to a given ecological setting (see Box 4). Many of the Ag-En hotspots of concern today are likely to have already occurred somewhere on the globe. They have not only been experienced elsewhere, but many of those experiences have already been described in academic journals, popular magazines and in the "grey literature" (unpublished reports). This notion also reinforces the value of historical research for hotspots projections. By using historical examples of what could happen under a "business-as-usual" scenario (i.e. no changes in human or climate behaviour or decision-making policy concerning the adverse interactions between agriculture practices and environment processes), potentially surprising outcomes of those interactions can be exposed to policy- and other decision-makers before they occur. Hence, some supposedly unknowable surprises can be revealed before they have a chance to occur ... and surprise policy-makers (Streets and Glantz, 2000).

Undertaking Ag-En hotspots audits represents a unique niche for FAO. It would also help to identify FAO's "competitors" in a hotspots monitoring activity and would help to avoid duplication of effort. It would also help to identify partners for a collaborative hotspots monitoring and reporting effort.

Some overlap among environmental hotspots-related activities could prove to be beneficial. The first global hotspots audit should be undertaken in the near future, and its initial findings placed on a user-friendly Web site. If the information derived from the global hotspots audit can be shown to be of value to governments and individuals, it could draw additional attention to hotspots themselves, as well as to the hotspots activity's contribution to environmental management from sources within FAO, and from other sources such as governments and research institutes.

If the audit is a cooperative effort among, for example, various groups in FAO and other organizations, such as the US National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR), or a UN agency, or a combination of UN agencies and private consultants, the task would be to the benefit of all partners. Such a cooperative Ag-En hotspots audit would probably generate a higher level of reliability in the hotspots products (i.e. outputs) and would increase the use and value of the hotspots Web site. SDRN would be in a position to become an authoritative voice on Ag-En hotspots.

|

Box 4. Land Degradation On about one-fourth of the world's agricultural land, soil degradation is widespread, and the pace of degradation has accelerated in the past 50 years. In developing nations, productivity has declined substantially on about 16 percent of agricultural land especially on cropland in Africa. The annual loss of agricultural land due to degradation is thought to range from 5 million to 12 million hectares, or about 0.3 1.0 percent of the world's arable land.

Estimates of the effect of degradation on agricultural productivity vary, but clearly the impact is significant in some regions. From 1945 to 1990, the cumulative crop productivity losses from land degradation have been estimated at about 5 percent worldwide, which is equivalent to a yield decline of 0.11 percent per year. In Africa, however, it is estimated that cumulative crop yield reductions due to past erosion have averaged about 8.2 percent for the entire continent and 6.2 percent for sub-Saharan Africa. Source: Global Environment Facility, 2002: The Challenge of Sustainability. Washington, DC: GEF. 20 21. |

Undertaking hotspots audits at two-year intervals provides a "breathing space" for the auditors. Within this time interval, they can review and re-evaluate the appropriateness of their indicators, monitoring and methods. It allows for a review (also called a "hindcast") of previous forecasts, projections and responses that had been made in the preceding two years. The five-year interval for the projection of hotspots developments is a time frame of concern to political decision-makers, as it is often within their period of political responsibility. These medium-term projections could be made on the basis of a "foreseeability analysis", as discussed earlier.

Decision-makers are not likely to feel a great deal of responsibility for future events that might occur well beyond their time in office. While a ten-year projection can be extrapolated under a "business-as-usual scenario," it runs the risk of being treated as too speculative.

The financial costs associated with the first audit and with the development of the Web site will depend on several factors. The least expensive and perhaps fastest way to develop a hotspots activity would be for an FAO person to undertake, in a preliminary way, the initial audit within FAO. Alternatively, a combination of an FAO person or persons with an outside consultant could be invited to undertake the task. Also, a consultant could be retained to undertake the worldwide audit, which could be viewed as a prototype. By labelling the activity as a prototype, it would be considered for what it is: an experiment that, if meaningful, would be continued. The various audits could be undertaken in parallel rather than in series. A more comprehensive audit would also be of considerable value, but would require more resources, more time and possibly involve more people.

As a prototype, the audit could be carried out at least three times in a five-year period. This would provide the SDRN with time to review and assess the value of the hotspots assessment and its use by decision-makers. There is a risk, however, that if the activity is not labelled as a prototype and the audit is not a comprehensive one, it could be seen by others as an opportunistic, non-authoritative endeavour.

"Present futures" has been used in a different form elsewhere and has even been proposed by the IPCC as one approach that could be undertaken for impact scenarios for climate change [see IPCC Web site]. It is referred to as "forecasting by analogy" (Glantz, 1988, 2001). Similarities as well as differences among Ag-En hotspots in different geographical locations need to be explicitly identified in order to minimize the possibility of relying on misleading or false analogies. Thus, analogies for present-day hotspots must be carefully and thoughtfully identified.

Those who identify hotspots could become involved in a "blame game" by, for example, having to identify governments, groups or policies that were responsible for or contributed to the adverse impacts of the interactions between agricultural activities and environmental processes. This is not an insignificant consideration, as potentially sensitive political issues are often involved.. While government leaders like early warnings, they do not like to be identified in a bad light, that is, they do not want to appear as the party responsible for inaction. Hence, there is a need to identify how best to inform decision-makers and the public at the same time. This, however, could be a more balanced activity if in the hotspots of concern one also identifies "bright spots," locations where positive changes are or have taken place at the Ag-En interface.

There is a need for hotspots education. Creating an Ag-En hotspots audit and reporting the results on the Internet is an important step toward educating policy-makers at all levels of society, from local to global, and the general public about where, when, how and why such hotspots can and do develop. Some of the educational lessons drawn from an audit will be case- or time-specific, while other lessons will prove to be more generally applicable to Ag-En interactions. Creating awareness, if not taking immediate action, is a major as well as necessary step toward eventually addressing the underlying causes of Ag-En hotspots, and not just reacting to the apparent catalyst. Without awareness, there can be no hope for timely and appropriate intervention to arrest and possibly reverse the change from hot toward the hottest of hotspots.

There is also a need for hotspots re-education. Because education is not a one-time activity, constant reinforcement will be needed of the original educational activities relating to Ag-En hotspots. This will require periodic updating with new information about positive and negative changes in hotspots, identification of emerging hotspots, adverse changes in AOCs, and the identification of potential flashpoints. Doing so will minimize a tendency of policy-makers and the public to "backslide," that is, to stop paying attention to what is happening around the globe with regard to the Ag-En interface. However important the Ag-En hotspots might be now or in the future, people making decisions at all levels of society are confronted by many situations that require immediate attention. Thus, once begun, a hotspots activity should include continuing re-education (i.e. reminding readers of the "basics"), in addition to providing updates on new hotspots as well as bright spots.

For a hotspots Web site, FAO has the option to develop and maintain either a passive, an active, or an interactive Web site. A passive Web site would provide baseline information on Ag-En hotspots, which would be updated infrequently and presented on a "take it or leave it" basis. At the least, a passive Web site would provide FAO with a presence in the area of hotspots identification and monitoring. It would demonstrate an institutional interest in the notion of hotspots.

An active site would require frequent and routine updating, as new information becomes available and additional links to new sources of information are identified. New material would be added, as the monitoring of the specific hotspots progresses beyond the baseline.

An interactive Web site does all that an active one does, but it allows for active, almost real-time participation by visitors to the Web site. It can do this by:

posing questions to visitors interested in agriculture's impacts on the environment;

encouraging feedback on controversial issues; and

by engaging visitors in the search for or monitoring of areas of concern (AOCs) and hotspots.

There are many interesting aspects of an interactive Web site that could be developed to the benefit of FAO and the visitors to site, which could also include short guest editorials.

The SDRN should consider creating a "hotspots idea bank". Located on the hotspots Web site, suggestions about various aspects of hotspots would be raised for open discussion in an electronic forum, managed by those in charge of maintaining the Web site. People would be encouraged to provide information on worrisome land transformation, and on potential and actual hotspots that might have been overlooked in an annual hotspots assessment. An Idea Bank would also introduce to the general public the notions of present futures, forecasting by analogy, business-as-usual scenarios, CEPs related to agriculture, foreseeability analysis, and so forth. In this regard, the hotspots Web site would fulfil an educational function, making it interactive as well as active.

The notion of an audit is a effective one; everyone knows about audits. An Ag-En audit, however, would be userfriendly, and would necessarily be undertaken in cooperation with the group(s) being reviewed within FAO, other UN agencies, and the geographical regions being audited. Such an audit would be a benefit to all, i.e. a winwin situation. Governments would be alerted to emerging or worsening environmental problems involving agriculture. FAO, for its part, would be in a position to give support to those governments or decision-makers who are willing to address Ag-En hotspots.

An FAO hotspots activity can build (i.e. "piggyback") on the efforts of other hotspots-related activities already underway. By building on and working in cooperation with other activities related to hotspots, FAO can avoid duplication of effort. More importantly, FAO would not have to start from zero with respect to identifying Ag-En hotspots, nor would it have to rely on its own resources for such a potentially major ongoing task.

Putting the findings of the first and future hotspots audits on the Internet would give FAO and SDRN a definite presence in the area of Ag-En hotspots identification, monitoring, forecasting and, perhaps more importantly, "foreseeing". Hotspots audits would place SDRN/FAO in a leadership position on Ag-En hotspots, using an invisible hand (for example, this could be accomplished by assembling people who have the same Ag-En hotspots concerns). Aside from the FAO December 2002 workshop on hotspots, there has not yet been any formal meeting focused on Ag-En hotspots, although there have been publications on related topics.