Peter Beers

Biosecurity Australia, Department of Agriculture Fisheries and Forestry

Edmund Barton Building, Kings Avenue

Canberra, Australia

[email protected]

Beers, P. 2005. Aquatic disease emergencies and implications to international trade. p. 41–45. In: Subasinghe, R.P.; Arthur, J.R. (eds.). Regional workshop on preparedness and response to aquatic animal health emergencies in Asia. Jakarta, Indonesia, 21–23 September 2004. FAO Fisheries Proceedings. No. 4. Rome, FAO. 2005. 178p.

ABSTRACT

The threat to international trade as a result of aquatic animal disease emergencies is growing. Increasingly, the response to health emergencies is to guard aquatic animal resources from disease in order to protect environmental values, investment, production, market access and consumer confidence. The Sanitary and Phytosanitary Agreement (SPS Agreement) of the World Trade Organization (WTO) provides the international framework within which governments respond to disease emergencies. The SPS Agreement provides special status to the recommendations of the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) that deal with trade in aquatic animal commodities and related matters. The effectiveness of emergency response procedures will inevitably impact on the response of trading partners to disease threats.

INTRODUCTION

The sources of aquatic animal products and the patterns of international trade in them are changing. Aquaculture production is growing rapidly, at a higher rate than for the terrestrial farmed meat production sectors (since 1970, at 9.2 percent per annum compared to 2.8 percent). In the same period, the capture fisheries sector has only grown at 1.4 percent per annum. About 27 percent of aquatic animal production (by weight) is now from aquaculture. The pattern of international trade in aquatic animal products is also changing, and 37 percent of aquatic animal production is traded internationally, with significant shifts in the source and destination of the product (FAO, 2002).

Aquaculture is an innovative industry; many species are being cultured, in many locations, under a variety of environmental and husbandry conditions. This has lead to new challenges, particularly when new disease syndromes emerge, often precipitated by high stocking densities, exposure to alien pathogens, stressful environmental conditions and inadequate husbandry.

Investment in aquaculture and the property values of capture fisheries bring new economic imperatives to derive a return and protect the investment from threats such as disease. Disease outbreaks are a common event in modern aquaculture, and concerns of spill-over into wild populations are regularly aired. In light of this, the response to dealing with and preventing aquatic animal disease emergencies is changing.

EMERGENCIES

Emergency situations can arise for different reasons, such as environmental disasters, significant disease occurrences and residue findings. The common result is that sudden and urgent action is required to manage the situation to minimize losses. Disease emergencies can take several different forms - the recognition of a novel disease, the appearance of a disease in a new location or in a new host species (including humans), or a disease taking on a more virulent form. A rapid response is required to assess the situation, limit further biological losses, stop spread and provide reassurance to markets.

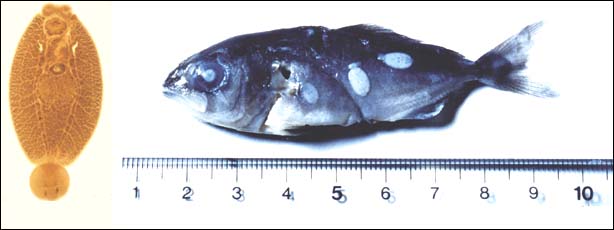

DV LIGHTNER

A juvenile P. monodon with distinctive white spots of WSD

In recent times, there are many examples of disease emergencies affecting aquatic animals, such as whitespot, Taura syndrome, infectious salmon anaemia and Koi herpes virus. It is reasonable to expect that aquatic animal emergencies will continue to occur for the foreseeable future because of the widespread movement of genetic materials for aquaculture purposes, the movement and reswimming (re-immersion) of live product for human consumption, the movement of aquaculture species into environments where they encounter new pathogens, the adaptation of new aquaculture species to commercial production exposing them to hitherto unrecognized pathogens and so on.

With the terrestrial animal industries, disease emergencies are frequently associated with the disruption of markets for two reasons: firstly, from the loss of consumer confidence and their switching to alternative products and secondly, from loss of market due to technical impediments. The response to the emergency, especially the level of trust in the authorities undertaking the response, will be instrumental in determining how rapidly the market can be regained.

Historically, there have been few restrictions on the international movement of aquatic animals and their products. Thus the biological loss of production caused by the disease emergency has been in general greater than losses due to disruption of markets, though the loss of markets to competing traders may have a continuing longer-term impact.

This is changing as the economic, environmental and social values of aquatic animals are recognized and as the increased threat of disease spread is appreciated. In general, restrictions in response to emergencies are likely to be directed at the movement of live animals and their genetic materials. However, it should be expected that increased scrutiny will be paid to the movement of aquatic animal products during disease emergencies, especially to those from emergency harvest or those that are not highly processed.

WORLD ORGANISATION FOR ANIMAL HEALTH - OIE

International biosecurity standards for the movement of aquatic animals and their products have lagged behind those for terrestrial animals. As aquaculture has increased in importance, international standards have been developed by the World Organisation for Animal Health (the Office International des Épizooties, OIE). The diseases addressed by the OIE have reflected the species that are of importance to aquaculture and the state of knowledge. The movement of broodstock and genetic materials have been the focus of its activities, but more recently the movement of products is being increasingly considered.

The current OIE Aquatic Animal Health Code 2004 - the Aquatic Code (OIE, 2004) contains recommended measures for the movement of live aquatic animals and their genetic material susceptible to the listed diseases. The Aquatic Code also contains recommendations for dead, uneviscerated fish and dead crustaceans of species susceptible to the OIE-listed diseases. The Aquatic Animal Health Standards Commission will be redrafting the Aquatic Code to introduce the concept of “safe commodities”. These are commodities that can be traded safely, regardless of the animal health status of the source. The Commission will also attempt to grade the level of risk for other commodities.

DV LIGHTNER/P. SAIBABA

Carapace from a juvenile P. monodon with WSD. Calcareous deposits on the underside of the shell account for the white spots

Member countries of the OIE also have obligations with regard to reporting particular disease occurrences through the OIE to the international community. Disease reporting is intended to assist in minimizing disease spread and aiding disease control. OIE members are obliged to report not only the occurrence of disease but also the presence of the causative agent in the absence of clinical disease.

In certain circumstances, such as a change in disease status or where information will be of epidemiological significance to trading partners, reports must be made within 24 hours. This is commonly referred to as emergency reporting. Situations covered by emergency reporting include the outbreak of a disease in countries or zones previously considered to be free, occurrence of a listed disease in a new host species, identification of a new strain or disease manifestation of a listed disease, situations where a listed disease has potential to spread internationally, newly recognized zoonotic potential for a listed disease and recognition of new emerging diseases and pathogens.

The Aquatic Code also provides rules by which a free status can be restored to a country or zone that has suffered a disease outbreak. In the case of “stamping out”(i.e. disease eradication), this relies on following the methods detailed in the appropriate chapters of the Aquatic Code, a surveillance scheme and no new infections being recognized.

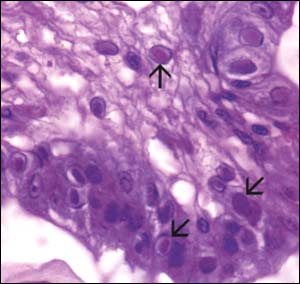

DV LIGHTNER

Histological section from the stomach of a juvenile P. chinensis infected with WSD. Prominent intranuclear inclusion bodies are abundant in the cuticular epithelium and subcuticular

Timely and accurate reporting to the OIE is usually an important consideration when assessing trading partners and responding to disease emergencies. Members are also to provide information on control measures taken to prevent spread, including on live animals, animal products and other things that could transmit disease.

Health certification is the basis of much international trade where measures are used to address sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) concerns. Unreliable and inaccurate reporting of disease emergencies may have a broader effect on the trading relationship, spilling over into the acceptance of routine certification.

DV LIGHTNER/F. JIMENEZ

Juvenile, pond-reared P. vannamei (c - from Ecuador; d - from Texas; e - from Mexico) showing melanized foci mark sites of resolving cuticular epithelium necrosis due to TSV infection.

THE AGREEMENT ON THE APPLICATION OF SANITARY AND PHYTOSANITARY MEASURES

The World Trade Organization's (WTO) Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (SPS Agreement) provides a basic right to WTO member countries to take necessary measures to protect human, animal or plant life or health. With this right come certain obligations, including that such protective measures must be based on a risk assessment or conform to an international standard. In the case of aquatic animal health, the measures in the Aquatic Code are the relevant international standards. If an aquatic disease emergency involved a disease listed by the OIE, a WTO member would be justified in restricting trade to the extent specified in the Aquatic Code.

WTO members are also able to take provisional measures in cases where relevant scientific evidence is insufficient for the risk assessment. This is often the situation in aquatic disease emergencies while the disease agent is being identified, the extent of its spread determined, the effectiveness of control measures assessed, and trace back and trace forward investigations are continuing. A WTO member adopting provisional measures must consider the available pertinent information, including international standards, seek further information to assess the risk and review the measure in a timely manner.

In practice, trading partners are becoming more likely to restrict trade in response to an aquatic disease emergency if they perceive a threat to their own aquatic resources. Such restrictions will be minimized by accurate international reporting and prompt action to control the outbreak. Previously prepared contingency plans effectively implemented increase the probability that disease outbreaks will be efficiently controlled. Obtaining cooperation from all of the participants in the midst of a response is likely to be difficult and may compromise the potential effectiveness of control and eradication. Trading partners need early and accurate advice, which is frequently updated, if they are to have confidence in the response and remove unnecessary trade restrictions.

Individual aquaculture producers can practice on-farm biosecurity to help minimize losses and facilitate a faster return to market. The OIE's Aquatic Animal Health Standards Commission is introducing the concept of “compartment”into the Code, which will help facilitate recognition of a higher health status on individual farms based on their health status, surveillance, control and biosecurity measures.

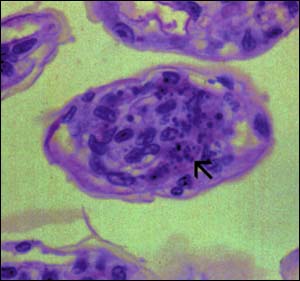

DV LIGHTNER

Focal TSV lesions in the gills (arrow). Nuclear pykinosis and karyorrhexis, increased cytoplasmic eosinophilia, and an abundance of variably staining generally spherical cytoplasmic inclusions are distinguishing characteristics of the lesions. 900x magnification.

CONCLUSIONS

At present, the impact on international trade resulting from aquatic disease emergencies is not great when compared to impacts that follow disease emergencies affecting terrestrial animals. This is not to diminish or understate the economic, social and environmental losses that occur in aquatic disease emergencies, particularly when there are severe biological losses in the affected species. However many countries have few biosecurity controls on the movement of aquatic animals and their products when compared to the terrestrial animal situation. This approach is changing with the recognition of the value of wild fisheries and the level of investment in aquaculture.

The SPS Agreement provides for the use of biosecurity measures to protect life and health. The OIE has disease-reporting obligations and recommendations for trade in aquatic animals and their products with regard to listed diseases. Although rapid and accurate reporting of aquatic disease emergencies may have consequences for trade, the building of trust will have longer-term benefits. Trust is the basis of trade, the international trading system and its certification system for SPS matters.

Early and accurate reporting of disease emergencies helps to build trust and facilitates the reinstatement of normal trading relations following a disease emergency. The longer access to a market is lost, the more difficult it becomes to regain market share taken by competitors and to rebuild commercial confidence as a reliable supplier.

For countries to meet their SPS obligations and international standards of the OIE Aquatic Code, a suitable infrastructure is required. The aquatic animal industries are growing globally at a rate faster than the development of the supporting infrastructure and expertise. SPS capacity can be strengthened in a number of ways, and this workshop will offer guidance and assistance to this end.

LITERATURE CITED

FAO. 2002. The state of world fisheries and aquaculture 2002. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome. (available at www.fao.org)

OIE. 2004. Aquatic animal health code, 7th Edn, Office International des Épizooties, Paris. (available at www.oie.int)

Juan Lubroth1, Peter Roeder1, Moisés Vargas-Terán2, William Amanfu1, Vincent Martin1, Wolfgang Boehle3, George Chizuka4, Carolyn Benigno5, Akiko Kamata1 and Fairouz Larfoui1

Lubroth, J., Roeder, P., Vargas-Terán, M., Amanfu, W., Martin, V., Boehle, W., Chizuka, G., Benigno, C., Kamata, A. & Larfoui, F. 2005. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations' Emergency Prevention System (EMPRES-Livestock) and experiences in developing countries. p. 47–65. In: Subasinghe, R.P.; Arthur, J.R. (eds.). Regional workshop on preparedness and response to aquatic animal health emergencies in Asia. Jakarta, Indonesia, 21–23 September 2004. FAO Fisheries Proceedings. No. 4. Rome, FAO. 2005. 178p.

1 Animal and Health Service

Animal Production and Health Service

FAO, Rome, Italy

[email protected]

ABSTRACT

FAO's Emergency Prevention System for Transboundary Animal and Plant Pests and Diseases (EMPRES), promotes the effective containment and control of the most serious epidemic livestock diseases, such as foot-and-mouth disease, rinderpest, contagious bovine pleuropneumonia, avian influenza, classical swine fever and Rift Valley fever, some which have public health implications. EMPRES also attends to newly emerging diseases and applies methods of progressive elimination on a regional and global basis through international cooperation involving (i) early warning, (ii) early reaction, (iii) enabling research and (iv) coordination. Major economic losses to livestock and producers the world over due to major outbreaks of transboundary animal diseases (TADs) such as foot-and-mouth disease (1997–2003), classical swine fever in the Caribbean and Europe (1996–2002), rinderpest in the Somali ecosystem (2001 and 2003), and Rift Valley fever into the Arabian Peninsula (2000) have been the main stimulus for the initiative to create a Global Framework for the Progressive Control of TADs with the Office International des Épizooties. Both organizations have examined the problem of TADs from the perspective of the complexity of the world food chain and human welfare, as well as the international public goods of equity, conservation of natural resources and public health and propose that effective prevention and progressive control of the major transboundary animal diseases is an essential contribution to the achievement of the Millennium Development Goals. The objectives of the GF-TADs initiative are to: safeguard the livestock industry of developed as well as developing countries from repeated incursions of infectious disease epidemics, to improve food security and incomes of developing countries, and to promote safe trade in livestock and animal products at the national, regional and international levels. These goals can be best achieved if the major TADs are controlled at source of infection, which is mainly in the developing countries.

INTRODUCTION

The overall priority of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) is the encouragement of sustainable agriculture and rural development. This priority is met by FAO's long-term strategy to increase food production and food security while conserving and managing natural resources and reducing poverty. According to its constitution and mandate, granted by the Member Countries, FAO provides independent advice to governments on agricultural policy and planning, as well as on the legal structures needed for development (including rural development, food security and the alleviation of poverty); development assistance through a wide range of technical assistance projects; the collection, analysis, interpretation and dissemination of information relating to food, agriculture, forestry and fisheries; and offers reference and educational material to farmers, scientists and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) so as to enable rational decisions on planning, investment, marketing, research and training. FAO provides a neutral forum where all nations can discuss, formulate and negotiate policy on major food and agriculture issues.

THE PRIORITIES OF THE FAO

The five corporate strategies expressed in FAO's Strategic Framework 2000–2015 are:

improving decision-making through the provision of information and assessments and fostering of knowledge management for food and agriculture.

In 1994, the Director-General of FAO established two priority programmes in support of such strategy, the Special Programme in Food Security (SPFS) and the EMPRES1. The two components of EMPRES are those of the desert locust in crops and the livestock component that focuses on epidemic animal diseases. The latter is placed within the Infectious Diseases Group, Animal Health Service (AGAH) within the Division of Animal Production and Health (AGA). The EMPRES concepts are encompassed in all five of the FAO priorities.

THE EMPRES VISION AND CONCEPT

FAO, within its global mandate related to animal health, has traditionally played an eminent role in the fight against epidemic diseases of livestock.2 However, upon taking office, the Director-General decided to step up FAO's role in the control and prevention of emergencies, to respond to the need to develop more effective mechanisms that would alert Member Countries to impending transboundary disease problems, as well as to develop FAO's ability to monitor and forecast the spread of animal diseases. The EMPRES concept encompasses animal diseases of a transboundary nature, which have been defined as:

“... those that are of significant economic, trade and/or food security importance for a considerable number of countries; which can easily spread to other countries and reach epidemic proportions; and where control/management, including exclusion, requires co-operation between several countries”.

The EMPRES vision is to promote the effective containment and control of the most serious epidemic livestock diseases. EMPRES also attends to newly emerging diseases and applies methods of progressive elimination on a regional and global basis through international cooperation involving (i) early warning, (ii) early reaction, (iii) enabling research and (iv) coordination.. The EMPRES Programme has established itself as a major initiative of FAO, well acknowledged as fulfilling an important development role. The World Food Summit in 1996 under Commitment Number3 and FAO conferences have emphasized its relevance and importance.

Funding for EMPRES activities is part of the FAO Regular Programme described under the Department of Agriculture. These activities are normative in nature and address aspects of disease spread and strategy development for containment, capacity building, awareness and technology transfer, as well as information in the form of manuals, booklets, CDs, videos etc. Included is the financial support to the World Reference Laboratory for Foot-and-Mouth Disease and the World Reference Laboratories for Rinderpest and other Morbilliviruses, located at Pirbright, United Kingdom, and Montpellier, France, and the extensive collaboration with the Joint Division of FAO/International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) in Vienna. There are some 30 FAO Collaborating Centres and Reference Laboratories that assist EMPRES in their speciality areas or competence in applied research for specific diseases of direct relevance to EMPRES needs. EMPRES also incorporates the Secretariat for the Global Rinderpest Eradication Programme, actively participates in Office International des Épizooties (OIE) standard setting upon request, and forms part of advisory or steering committees in several initiatives around the world (e.g. the Pan African Programme for the Control of Epizootics/African Union-Inter African Bureau for Animal Resources). Also within the Animal Health Service, the Secretariat of the European Commission for the Control of FMD resides, dedicating its efforts to prevent incursion of foot-and-mouth disease (FMD) into Europe, promoting applied research and technology exchange, and supporting countries neighbouring Europe in FMD surveillance activities. This commission, financed through a European Community (EC) Trust Fund, extends well beyond the European Union, to include 33 countries.

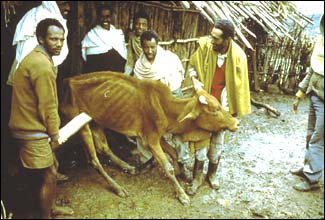

FAO

Rinderpest, also known as cattle plague, is characterized by fever, depression, dehydration, diarrhoea, and high mortality

FAO Member Countries requesting assistance can benefit from its Technical Cooperation Programme, which may provide funds (up to US$400000 per project), training, equipment, vaccine and expertise to meet priority development needs. EMPRES operates numerous emergency or regular Technical Cooperation Projects (TCPs, Figure 1) for several of the most devastating animal diseases such as FDM, rinderpest, contagious bovine pleuropneumonia, peste des petits ruminants, Newcastle disease, Rift Valley fever, classical swine fever (CSF), African swine fever, sheep pox, brucellosis and haemorrhagic septicaemia. In addition, inputs from FAO include: surveillance systems (including global information systems (GIS) based field observation/abattoir data software) known as TADinfo, emergency preparedness, contingency planning, veterinary vaccine technology transfer, participatory epidemiological approaches, enabling legislation and evaluation of veterinary services.

JUAN LUBROTH

Clinical signs of Rinderpest

The diseases or needs addressed by EMPRES were: In Asia, FMD, Rift Valley fever, CSF, rinderpest, peste des petits ruminants, information systems, project evaluation and border control. In Africa, contagious bovine pleuropneumonia, African swine fever, FMD, Rift Valley fever, rinderpest, peste des petits ruminants, Newcastle disease, veterinary vaccines, laboratory training and equipment, molecular analysis of viral strains, surveillance systems, participatory approaches to epidemiology and participatory disease search, modeling of disease transmission, remote sensing and prediction, animal identification and evaluation of legislation. In the Americas, EMPRES inputs included molecular characterization of FMD viral strains, the promotion of the Hemispheric Plan for CSF eradication, public awareness, surveillance methods and information systems.

Other activities in which EMPRES (including others within the Animal Health Service and AGA) has been involved include:

presentations at the Biological Weapons Convention meetings.

The EMPRES Projects depicted in Figure 1 (2002–2004) do not include trust-funded projects or specific extra-budgetary projects for agriculture or animal health where the Infectious Disease Group has held responsibility.

It is apparent to EMPRES itself that all its inputs are insufficient to curtail the devastation caused by transboundary animal diseases and their impacts on food security and the livelihoods of poor animal farmers, pastoral communities, and the viability of dairy cooperatives and commercial enterprises. The long-term vision of EMPRES is to have a large cadre of trained professionals and para-professionals that would curb disease incidence and implement the required control strategies through better surveillance, early warning, early detection and early reaction. As EMPRES works to meet these needs for individual countries, these inputs are often not sustainable for various reasons. These include such factors as: the poor animal health status of a neighbouring country; low efficiency in carrying out planned activities, inconsistent training; attrition of personnel (i.e. key individuals departing from public service for the acceptance of greater administrative responsibilities4, succumbing to disease5 or desiring to find a place within the private sector in clinical practice, pharmaceutical representation or consultancy). Recognizing that transboundary animal disease respects no political boundaries, EMPRES, has sought to work beyond individual country projects at the regional level in coordination with various countries and stakeholders. An initiative, in partnership with the Office International des Épizooties (OIE), to coordinate counter-epizootic measures and strengthen veterinary systems was therefore undertaken in 2002, under the working title: “The Global Framework for the Progressive Control of Transboundary Animal Diseases (GF-TADs).”

THE GLOBAL FRAMEWORK FOR THE PROGRESSIVE CONTROL OF TRANSBOUNDARY ANIMAL DISEASES (GF-TADS)6

Major economic losses to livestock and producers the world over due to major outbreaks of transboundary animal diseases (TADs) such as foot-and-mouth disease (1997–2003), classical swine fever in the Caribbean and Europe (1996–2002), rinderpest in the Somali ecosystem (2001 and 2003), and Rift Valley fever into the Arabian Peninsula (2000) have been the main stimulus for the initiative to create a Global Framework for the Progressive Control of TADs. The unprecedented epidemics, both in scope and geographical occurrence, of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) that came into international attention in Asia in 2004 are symptomatic of the problems facing disease control, regional collaboration and understanding of disease ecology for better prevention. Other diseases remain unchecked - such as contagious bovine pleuropneumonia in Zambia, Angola, DR Congo and Namibia or peste des petits ruminants in India, Bangladesh, North Africa and the Middle East. African swine fever still causes hardship for swine production in rural and peri-urban areas in Central and West Africa.

Several international institutions have emphasized the need to control TADs due to their devastating impact on livestock agriculture, trade and food security:

The WFS, five years later (2002), reiterated the 1996 commitment and called for specific action and voluntary financial contribution to the FAO Global Trust Fund to facilitate food security programmes and combat TADs.

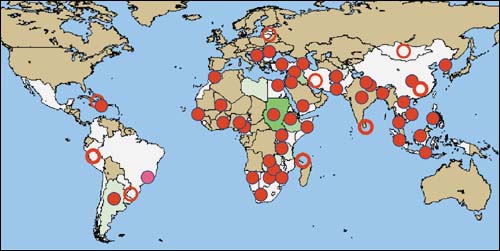

FIGURE 1

Technical Cooperation Projects 2002–2004; EMPRES (full

circle) and those with EMPRES involvement or of notable mention (open circles)

There is ample evidence from various studies that the risk of spread of TADs will increase unless concerted international actions are put into place for effective prevention and progressive control. This conclusion is predominantly based on predictions of an unprecedented growth of the livestock sector and of the consumption of livestock products, particularly in TAD-endemic developing countries. The predicted growth in livestock is expected to result in increased livestock farming in tropical/subtropical zones, with trends towards large farming units and increase in trade in livestock and livestock products through informal and formal markets regionally and internationally.

OIE and FAO have examined the problem of TADs from the perspective of the complexity of the world food chain and human welfare, as well as the international public goods of equity, conservation of natural resources and public health. Thus the GF-TADs that is being promoted by the two organizations proposes the effective prevention and progressive control of FMD and other major TADs as an essential contribution to the achievement of the Millennium Development Goals.

The goals of GF-TADs are:

to promote safe trade in livestock and animal products at national, regional and international levels.

The above goals can be best achieved if the major TADs are controlled at source of infection, which is mainly in the developing countries. The GF-TADs programme will be developed along four main thrusts:

A flexible Regional Thrust to take account of the regional priorities in terms of target disease, epidemiology and strategy for progressive control of FMD and priority diseases agreed through regional collaboration.

The Outputs for the initial six-year (2004–2009) period are:

strengthening of referral diagnostic and molecular biological capacity of FAO/OIE Reference Laboratories and a follow-up technology transfer to National Agricultural Research Systems (NARS), primarily through the established system of a network of national laboratories supported by the FAO/IAEA Joint Division and north-south/south-south partnerships.

The GF-TADs initiative is designed to provide strategic regional cooperation for the control of transboundary animal diseases by:

Implementation of Good Emergency Management Practices that include early detection, reporting and counter-epizootic measures. The epidemiologically based strategy advocated in the GF-TADs is founded on two notions: risk-based surveillance and risk-mitigation disease control.

USDA

Ruptured vesicles in the mouth of a cow affected by FMD

It is expected that the GF-TADs programme will oversee a flexible progression in disease containment according to the various target regions, addressing features of risk reduction, evolved and strengthened national/regional control programmes, and the creation and maintenance of free zones or prescribed disease free zones. Verification of disease and infection-free status will be a reiterative process of national responsibility to ensure safe animal trade.

In addition, research into a new generation of vaccines their delivery, and diagnostic tests that will advance disease control programmes, early detection or prevention is being considered by several research centers with vast experience in FMD. Meetings with partners in the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia and Canada have already taken place to determine researchable priorities with the hope of obtaining promising advances in short periods of time, after which pilot projects could be carried out. This research programme is suggested to be coordinated with the Global Framework by an Inter-Agency Steering Committee.

It is expected that the Joint FAO/IAEA Division will continue to provide transfer of the new diagnostic technologies to developing countries as they become available, building on its 30-year experience of coordinated research and technical cooperation programmes. It is envisaged to include a financial subcontract arrangement with the FAO/OIE World and Regional Reference Laboratories in order to enhance their capacity for rapid and coordinated provision of authoritative diagnosis of epidemiologically important outbreaks, characterization and analysis of the genetic and antigenic make up of causal agents, monitoring of regional and global trends in pathogens and capacity building in national and regional laboratories. Other advanced research institutes will be contracted for specific expertise in the development of predictive methodologies and sensors, novel diagnostic techniques and more efficacious vaccines.

EARLY WARNING ACTIVITIES

Early warning concept

Early Warning was seen from the outset as a key component of EMPRES. The 1994–1995 Programme Review Report, Chapter V, observed thus:

“Early warning of T-PP/AD9 situations is an important function of FAO, which has to rely largely on national systems for identifying and reporting outbreaks. Strengthening of national and regional capacities has thus been an important priority for FAO”.

Early warning has been defined as all disease initiatives, which predominantly would be based on epidemiological surveillance, that would lead to improved knowledge of the distribution of disease or infection and that might permit the forecasting or further evolution of an outbreak.

Capacity building in surveillance and early warning

This has been undertaken through a series of regional and national workshops, especially in Africa, North Africa and the Near East and in Asia. These training activities have been augmented by two specific manuals on surveillance and participatory epidemiology.

A development of greatest impact has

been the development of a hierarchical software system aimed at assisting

epidemiological surveillance, collection and analysis of GIS-based animal

disease information at the national, regional and global levels. This unique

system, called TADinfo, has been adopted or is being evaluated in several

Member Countries. The system is described on the EMPRES website:

www.fao.org/ag/AGA/AGAH/EMPRES/tadinfo2/e_tadinf.htm

Regional TADinfo is currently being field tested by the Southern African Development Community Regional Epidemiology Unit. A “global” TADinfo system is expected to act as a major platform for the proposed FAO-OIE-WHO Global Early Warning System for Transboundary Animal Diseases (GLEWS). The global aspects are under the incipient EMPRES-i (i for information, intelligence and intervention) database for disease tracking and references linked to the FAO Global Livestock Production and Health Atlas (GLIPHA).

Early warning projects

EMPRES-Livestock has been providing technical assistance to three major regional projects:

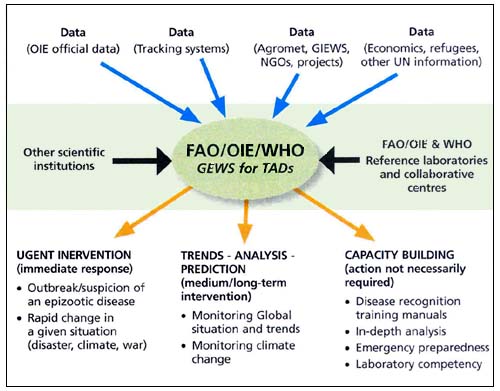

FIGURE 2

Schematic representation of the FAO/OIE/WHO Global Early

Warning System (GLEWS) and response

Pipeline projects

EMPRES-Livestock is developing three pipeline projects that are likely to have a long-term impact on early warning for transboundary animal diseases. The first involves capacity building and development of an early warning system for Central Asia, with ear-marked funding from the FAO Trust Fund; the second involves enhancing national up-take of the TADinfo system -which is still largely unfunded; and the third is expected to be developed jointly with the OIE and WHO as the Global Early Warning System for Transboundary Animal Diseases (GLEWS). The FAO-OIE-WHO GLEWS is being designed along the principles shown in Figure 2.

SPECIFIC EXAMPLES FOR COOPERATION AND LESSONS TO BE LEARNED

The Global Rinderpest Eradication Programme (GREP)

The immediate post-World War II period in Asia was followed by a major rinderpest epidemic in the 1950s affecting many countries in south and eastern Asia. National and regional programmes were set up to control rinderpest, the principal strategy for which was mass vaccination of the national herd. Once under control and with considerable investment, the disease likely persisted only in southern India and southern Pakistan. Nevertheless, the rinderpest control programmes initiated from 1987 were still based on the strategy of national mass vaccination, with relatively little impact on the perceived incidence of rinderpest in the region (Figure 3). The breakthrough happened once the region started to adopt an epidemiologically determined approach to disease eradication. In India, this led to recognizing that the disease was really endemic in the southern states (Tamil Nadu, Karnataka and Andra Pradesh) and that rinderpest elsewhere occurred by epidemic extension. Indian veterinary authorities concentrated their vaccination programme in the southern states and stopped vaccination in the north. No further outbreak of rinderpest has been reported in India since September 1995, and vaccination ceased in 2001. It is likely that the entire country will gain freedom of disease status by the end of 2004.

Similarly, by analysing the epidemiology of rinderpest in Pakistan and Afghanistan, it became obvious by 1996 that the 1994–1995 rinderpest epidemic in the Northern Areas of Pakistan and the 1995 and 1997 outbreaks in Afghanistan had merely represented a disease incursion from the endemic areas of southern Pakistan. On the three occasions, the outbreaks were controlled by targeted, peri-focal intensive vaccination without resorting to nation-wide blanket rinderpest vaccination.

During the regional workshop jointly organized by FAO/EMPRES and the Animal Production and Health Commission for Asia (and the Pacific [APHCA]) in 1998 in Sri Lanka, each country presented its rinderpest status. It became clear that in the entire South and East Asia, there was only a single endemic focus in southern Pakistan. As a consequence, there was no justification for countries to conceive expensive programmes involving national or regional mass vaccination campaigns against rinderpest, but rather to focus on the nidus of infection.

In Pakistan, the veterinary authorities were motivated since 1998 to pursue a strategy that would be epidemiologically determined rather than the 100-fold more costly generalized blanket vaccination campaign. In the following two years, Pakistan embarked on clinical and serological surveillance with targeted vaccination of buffalo herds in the presumed endemic areas encompassing the dairy colonies of Karachi in Sindh Province. The last recorded case of rinderpest in Pakistan was in 2000, with a status of provisional freedom from disease declared in 2003. This once-Asian disease may now have been eradicated from the continent; yet, active surveillance in the most remote villages must be exhaustive.

The Middle East also experienced an epidemic of rinderpest in the 1980s, and localized outbreaks in 1991 and 1994 occurred in Turkey and northern Iraq. Outbreaks were also recorded in Saudi Arabia, Oman and Yemen between 1994 and 1996. Molecular analysis of virus samples from the region showed that the causative strains were of the Asiatic lineage, suggesting a South Asian rather than an African link to source of infection. The GREP strategy in 1994–1996 shifted from advocating mass vaccination to one of targeted control. This concentrated on three fronts: controlling rinderpest in South Asia and surveillance plus targeted control in the Kurdish ecosystem and southern Yemen, i.e. the presumed primary endemicity. Although verification is still required, rinderpest seems to have been eliminated from the Middle Eastern region without further recourse to regional blanket vaccination. Only Syria still vaccinates its national herd, although there is a commitment to halt the practice at the end of 2004. In December 2003, GREP/EMPRES held a joint Technical Advisory Meeting with the OIE in Lebanon to provide the assistance required for countries in the Middle East and Arabian Peninsula (and Iran and Iraq) to meet the internationally recognized goals of freedom from disease and infection.

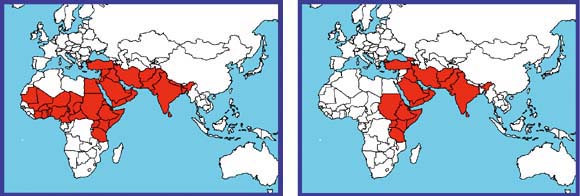

| FIGURE 3 In the early 1980s (a), rinderpest was known to have been present in many countries, extending from Mauritania in the west to India in the east and as far south as Tanzania in Africa (years earlier, rinderpest extended to countries further east, including the Philippines). By the early 1990s (b), western and most of central Africa had been cleared of rinderpest, but it was still prevalent in eastern Africa. Many countries in South Asia, the Near East and the Arabian Peninsula continued to be affected. Even Europe was affected when rinderpest occurred in Georgia (and eastern Russia - not shown). In 2001 (c), there were suspicions of rinderpest persistence only in southern Sudan, the Somali ecosystem and Pakistan. The Pakistan reservoir was eliminated in 2002 (by virtue of Pakistan/EC/FAO joint effort), and this country declared provisional freedom in 2003 with subsequent recognition by the OIE. The first two maps (1980s and 1990s) show rinderpest infection status of countries by depicting whole countries as being infected, which epidemiologically is known not to be the case, even where disease occurrence was reported. The map for 2001 depicts livestock populations in which infection was suspected to be persisting and indicative of an improved epidemiological understanding. Currently, in 2004 (d), rinderpest virus is suspected to occur in the Somali ecosystem, crossing over several international borders | |

| |

| a) Early 1980s | b) Early 1990s |

| |

| c) 2001 | d) 2004 |

In Africa, the 10-year, multidonor programme coded JP-15 from 1964 to 1975 was based on blanket vaccination of the national herds throughout Tropical Africa. Although it was expected to have countries assume responsibilities, by 1982–1984 a pandemic of rinderpest had broken out in 20 countries of Tropical Africa stretching from Somalia in the east to Mauritania in the west. A new programme, the Pan African Rinderpest Campaign (PARC) was developed in 1986 with financial support primarily from the European Union. Initially, the approach was mass vaccination. It was not until the early 1990s that the approach of addressing the disease at source started to be vigorously pursued. Using community-based vaccination and disease search methodologies with several NGOs proved an extremely useful programme in remote areas and those under civil strife (e.g. southern Sudan, with its last confirmed case in 1998).

There is an urgent need to provide such a community-based animal health programme delivery system in the area that almost certainly constitutes the last rinderpest reservoir, situated in the Horn of Africa, and to institute specific actions aimed at eliminating foci of viral infection there. Fortunately, there exists a coordinated African programme with the work being undertaken predominantly through the Pan African Programme for the Control of Epizootics (PACE), implemented by the African Union/Inter-African Bureau for Animal Resources with financial support from the European Commission and the United Kingdom through its development agency. FAO and OIE, both on the advisory committee with PACE, assist in defining the actions required to define the rinderpest situation and bring about rapid elimination of the last reservoir of infection, with appropriate surveillance programmes to verify freedom.

One of the main lessons to be learnt from GREP is that the cost of a disease eradication programme can be reduced considerably by targeting disease control to epidemiologically defined endemic areas instead of undertaking blanket, mass vaccination of the entire national herd. The approach adopted by GREP since 1994 has involved five main thrusts:

taking expert advice both on an individual basis and through the mechanism of the International Technical/Expert Consultations.

GREP is the only existing global disease control programme and is the single most ambitious animal health programme. From the outset in 1992, it has had the stated goal of achieving verified worldwide freedom from rinderpest by 2010. Recognition for the achievements must be shared with others, notably the OIE; the European Union and European Commission; the Organisation of African Unity/African Union; the Animal Production and Health Commission for Asia and the Pacific; the governments of the Republic of Ireland, the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, the Netherlands and Japan; the International Atomic Energy Agency's Joint Division with FAO; and most importantly, the countries themselves.

The Hemispheric Plan for the Eradication of Foot-and-Mouth Disease - Americas

Control of this relatively new disease to South Americas10 has benefited from concerted action by the Pan American Health Organisation (PAHO) through the establishment of the Pan American Centre for Foot-and-Mouth Disease (Panaftosa), located in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. In 1978, the Inter-American Meeting, at the Ministerial Level, on Health and Agriculture agreed on the Hemispheric Plan for Eradication of FMD in the Americas. The three subregional plans focussed on the level of endemicity of FMD (none, as in North America; endemic - South America; and a third sphere reflective of risk and proximity). The South American countries formed a commission (Comisión Suramericana para la Lucha Contra la Fiebre Aftosa or COSALFA), which in its early years consisted of the official veterinary service representatives or Ministers of Agriculture, but today incorporates the private sector, through representatives from dairy cooperatives, rancher syndicates or presidents of rural associations sitting side by side with the government to strategize methods for control and evaluate performance, accountability and conformity. The Comisión meets annually and more frequently if an emergency arises (as it did in 2001). This partnership between the public and private sectors was extremely successful in Colombia in 1985, when a new type of FMD virus appeared in the Sabana de Bogota, in central Colombia. This particular virus appears to have been extinguished from circulation. In Argentina, this partnership extended this model to the rural communities and livestock associations, with the involvement of schools, churches, universities and police, which rapidly led to the countries' recognition of freedom with vaccination in the late 1990s.11

Some of the major contributions of Panaftosa in the field of FMD control are a better understanding of FMD epidemiology, persistent infections of cattle and buffalo, and vaccine use. Epidemiologists at Panaftosa devised a structure to correlate “ecosistemas”-virus ecological systems, land use, farming and husbandry practices, and cattle movement to identify primary endemic areas (i.e. virus maintenance areas), secondary endemic areas (areas of virus propagation) and epidemic areas (i.e. areas of explosive outbreaks). They showed that the most cost-effective and sustainable strategy for FMD control was that which targeted first the primary endemic ecosystem, which is highly correlated with a calf:cow ratio of 1. If disease is first brought under control in this ecosystem, it becomes relatively easy to achieve sustained control in the other zones and diminishes risk to elsewhere.

Panaftosa also provides regional reference diagnostic support and training, and independent vaccine evaluation for manufacturers (private or governmental). This last activity is highly relevant for FMD vaccine use elsewhere around the world, where such quality assurance is lacking. Today, major efforts by Panaftosa include country collaboration along adjoining borders and robust rural integration for animal health development.

Avian influenza - Asia, poultry, livelihoods and human health12

Official reports to FAO, OIE and WHO suggested that avian influenza, more commonly know as bird flu, started to assume epidemic proportions towards the end of the year 2003. However, recent, retrospective analysis suggests that in most countries the disease may have been around for many more months. This would signify that a major veterinary public and animal health problem and a socio-economic disaster of subcontinental scale unfolded itself before causing any widespread alarm. This in turn illustrates that the current avian influenza crisis is not just an emergency but also a symptom, reflecting major institutional and policy-level deficiencies that also need addressing.

The FAO/OIE/WHO Technical Consultation on the Control of Avian Influenza, held 3–4 February 2004, concluded that the current epidemic is evolving and is anticipated to continue to expand both in geographic distribution and incidence. Given that the virus circulation in the region is not considered to be under control, there is need for a concerted emergency response. Without the implementation of appropriate methods of disease control, the risk of epidemic spread to further countries, including those in distant regions, is likely to remain high, and the disease may persist as a result of infection becoming endemic in the domestic poultry population. There will be a continuing threat to human health as long as the infection is present in the poultry production systems in Asia.

As an emergency measure, the above scientific panel recommended that control programmes be immediately intensified and monitored, and that public education in veterinary training and national and regional capacity building, particularly for veterinary services, is an important part of the development of long-term surveillance and the control of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) and other priority diseases. National avian influenza task forces require major strengthening and improved surveillance. Transparent and timely reporting of infection to the OIE by the veterinary administration is required at the national, regional and international levels. Extensive international coordination should be established for short and long-term control of influenza viruses of human and animal health significance.

Preventing a similar emergency in the future makes it necessary to reflect on the factors in the Asian poultry subsectors that led to this problem. Of paramount importance is the human health risk posed by HPAI flare-ups and the threat emanating from the combination of wild bird reservoirs, backyard poultry and rapid intensification and industrialization. The meeting highlighted that the current spread of HPAI virus may be viewed as a consequence of failure of surveillance networks, early warning implementation, and control of movement of infection between domestic poultry. The HPAI crisis also serves to indicate the need for a veterinary surveillance framework for early warning of disease risk at the regional level, which should serve the needs of the agricultural and medical communities of the region and the wider international community. Regional networks for epidemiological surveillance, typing of influenza and other infectious pathogens, vaccine banks and contingency stocks of vaccines complying with OIE standards may all be necessary for timely national and international early warning and effective action. Novel approaches and thinking will almost certainly be required.

Rehabilitation and restructuring of the subsector should duly reflect the importance of the smallholder and the semicommercial sector. A sizeable segment of the poultry population remains within this sector. An estimated total of 200 million farmers, mostly keeping somewhere between 10 to 100 birds including chicken, ducks, geese, turkeys and quail, constitutes a vitally important contribution to the food and income security of the rural sector. FAO is especially concerned with the loss of livelihood for the proportion of dependent poor in the affected region. Not only poultry producers but also traders, processors, marketers and food vendors, as well as persons employed in the poultry sector, are at risk of losing their livelihood. Recovery of export capabilities for regional and international market access in compliance with OIE standards of the Terrestrial Animal Health Code is also crucial for the rural economy of some countries of the region.

While the present document seeks to categorize the support required today (Emergency Response), tomorrow (Emergency Prevention) and beyond (Rehabilitation and Restructuring), none of these components should be viewed in isolation. On the contrary, without integrating the immediate, medium and long-range responses required, there will be no effective containment of the current emergency.

The FAO Technical Cooperation Programme (TCP) has allocated US$5.5 million to assist countries in Asia with emergency/short-term support. Within this budget, US$2.7 million was approved by mid-February 2004 for one regional TCP covering Southeast Asia and six national TCPs (China, Pakistan, Viet Nam, Cambodia, Laos and Indonesia). At the time of this writing, September 2004, all six national TCPs are far in implementation and three subregional TCPs are underway, with two additional ones approved, with launching planned in the next four to six weeks (all regional TCPs cover 21 countries of the Region. See Table 1). Such TCP-mobilization for an animal health crisis was unprecedented in scope and nature. Some of these funds, however, have been used for advocacy channels to seek additional donor input successfully for countries or regional interventions. The emergency response cannot be viewed in isolation from the longer-term rehabilitation of the poultry sector, including supportive veterinary administrations and animal health services both in the public and private sectors.

TABLE 1

Regional support units identified for the

avian influenza emergency.

| East Asia | PR China, Japan, North Korea, South Korea, Taiwan Province of China |

| Southeast Asia/Oceania | Cambodia, Laos, Viet Nam, Thailand, Myanmar, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, East Timor, Papua New Guinea |

| South Asia | India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Bhutan, Pakistan |

The strategy decisions require early identification of the desired health status by production system, a timetable to achieve this, and surveillance systems and criteria required to permit re-opening of export markets in compliance with international standards. The inputs required for individual countries depend also on the level of risk of reintroduction of infection from sectors or regions that have not controlled or eliminated reservoirs of infection (and perhaps may never). For the moment, the situation in most of the Asia Region is far from clear, and the problem in some countries is still evolving.

In order to bring the diseases back in check, the affected countries are currently engaged in a number of the following disease emergency measures:

monitoring and resourcing of the entire control operation.

In terms of financial resources, the operations in the field are the most costly. The killing and disposal of birds demand large numbers of staff and involve high running costs for transport, earth moving equipment and various supplies. Round-the-clock deployment of staff resources is sometimes necessary in local and national centers. Considerable financial resources go to the compensation of the affected farmers.

On the basis of all the above considerations and taking into account the variable size of the country epidemics, a conservative estimate is possible. Preliminary figures suggest that the total campaign costs may amount to several million US dollars for each of the least affected countries and up to tens of millions of US dollars for the more seriously affected countries. However, the total costs for the control operations may continue to go up in the case of a prolonged campaign necessitated by the persistence of disease flare-ups in areas that were believed to have been freed from infection. This now brings the expenditure for the control of the avian influenza epidemic across the Asia Region, excluding China, to over US$250 million.

It is anticipated that more details on the total cost of the control of the disease; its economic impact; and the requirements for rehabilitation, restructuring and restocking will become available in the coming months. With more accurate information being collated, analyzed and synthesized, it also becomes more realistic to optimize control strategies in economic terms and base different scenarios on detailed and rigorous economic analysis.

Given the current deficiencies in disease reporting, there is an urgent need to enhance early and adequate risk assessment for use within the regions and to provide a wider warning to the international community.

The FAO/OIE proposal for strengthened surveillance and control of epizootic animal diseases - through support of disease surveillance units - is expected to operate at the regional level, placing emphasis on disease risk assessment and communication within each region. Through embedding epidemiologic expertise in regional specialized organizations whose mandate is to serve member states as well as to provide essential information for early detection of changing risk, benefits go to and ownership is with the countries in each region. Clearly, the avian influenza situation highlights the need for such a regionally focussed programme.

On a regional basis and under the guidance of the GF-TADs OIE/FAO steering committee, three Regional Support Units (RSU) (in East, South East and South Asia) have been identified to support regional needs on a range of animal diseases, working with and in support of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN); the Southeast Asia FMD, Animal Production and Health Commission of Asia and the Pacific; and the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC). The principal activities of the RSU are (in relation with national veterinary services) to:

arrange and participate in national and regional workshops.

Regional network for laboratory support

Networking of veterinary laboratories within regions, with support from international specialist (reference) laboratories has been of proven value in raising capacity and preparedness for diagnostic activities, and especially in introducing and establishing quality assurance. A support project for laboratories in the South, East and Southeast Asian region could play a very important role to network laboratories to raise cooperation within the region, with training and technical support from FAO/OIE Reference Laboratories (e.g. Weybridge, United Kingdom and Geelong, Australia). In addition to capacity building (e.g. to comply with OIE guidelines), quality control of laboratories and inter-laboratory proficiency testing will be promoted. Contract arrangement with OIE/FAO World and Regional Reference Laboratories should support authoritative diagnosis of epidemiologically important outbreaks, characterization and analysis of the genetic and antigenic make up of causal agents, and expert input into monitoring of regional and global trends in avian influenza circulation.

PARADIGM SHIFTS

It may appear as an insurmountable task: the Global Control and Eradication of FMD. However, understanding of where, how and when infections occur is key in defining strategies of intervention. Although the experience of the remarkable successes against rinderpest for some 50 years was based on widespread vaccinations with a vaccine unsurpassed in medicine that conferred life-long immunity (with concurrent circulation of a immunologic similar virus, peste des petits ruminants), today the strategy is on halting vaccination to identify areas of specific virus maintenance, and then targeting the specific population at risk with intensive vaccination with the object of immunosterilizing susceptible animals and banishing the virus from the particular ecosystem. Discovering where agents of disease are maintained is not an easy task and requires the participation of many sectors of society, perhaps the most important being at the local village level, and as such, participatory epidemiological approaches and the use of community animal health groups become essential. In contrast, FMD has several serotypes and the current vaccine does not confer long protection. But FMD viruses share with rinderpest virus, as with other disease-causing pathogens, primary endemic areas where the virus is maintained. The shift in strategy against FMD would be better served if FMD were thought of not as caused by one virus but by seven different viruses, with a plethora of variants, each of which can cause a similar clinical disease, but each with distinctive epidemiological parameters and varied biochemistry. It is then that we can begin to appreciate FMD dynamics and design strategies to tackle subtype to subtype, occurrence to occurrences in the field, and understand the behaviour of the virus within a particular ecosystem. Such focussed campaigns would become more rational and logistical, as well as scientific, than they are today. Likewise, the lessons learnt from the experience with rinderpest, which is approaching extinction, and international efforts required to maintain interest and momentum for active surveillance and verifiable freedom from disease and infection are most valuable. Thorough epidemiological understanding of host, environment and agent are to be applied - against FMD, rinderpest and other TADs.

Vaccines are tools that assist in protecting hosts from disease but may not eliminate infection. Intelligent use of these tools (i.e. targeted vaccination, information systems, animal movement management) is not widely applied. In the case of FMD where multivalent vaccines are applied, success may be better achieved with one serotype over another, or vaccines should be better tailored to select master seed vaccine strains that better protect against circulating strains. Cooperation and designing identical strategies across borders are essential in the attempt to decrease the load of agent circulation. With the exception of South America and perhaps part of Southeast Asia, this unification of strategies against FMD is not common. The Hemispheric Plan for the control of classical swine fever addresses this issue, but it is the responsibility of the national programmes to implement such plans with realistic strategies, with membership of the public and private sectors and follow through using self-realized performance indicators.

JUAN LUBROTH

Vaccination campaigns for the control of transboundary animal diseases, such as FMD, need to be coordinated at the central, regional and local level. Quality vaccines need to be approved by governments

To diminish the risk to the areas where a transboundary animal disease (or other) does not occur, engagement with countries and regional associations to assess out the environments where they do exist is essential, as proposed in the GF-TADs initiative. Paramount to the success of GF-TADs is the identification of primary endemic regions (i.e. hot zones). EMPRES and the GF-TADs initiative propose to address these issues to the interested investors.

CONCLUSIONS

This seminar on the emergency preparedness of transboundary animal disease in aquaculture, and fisheries in general, should ask: (1) What can be done to reduce the vulnerability of individual countries (vis-à-vis risk analysis and threat mitigation)?, (2) What can be done to streamline resumption of trade after an occurrence of disease (recovery and rehabilitation)? and (3) What can be done to enhance the capacity of a developing country's trading partners in meeting SPS (sanitary and phytosanitary) requirements?

From the perspective of transboundary animal diseases as dealt with by EMPRES, the reduction of the vulnerability of countries to disease exposure relies on their participation in ongoing regional and international efforts to curb disease incidence where such agents are known to occur naturally; on supporting efforts to identify ecological zones that are the origin of infection or where new pathogen subtypes emerge; and on undertaking prevention measures by applying risk mitigation, including networking with close and distant partners in an agreed development agenda. This latter point is essential, as it creates an understanding of risk assessment, risk management and risk communication among all involved. Thus it is to better to consider that a neighbour's situation (i.e. an incipient animal health problem) should be of concern to the region as a whole, and stimulate the preparation of contingency plans at that level prior to an emergency situation.

Among the tools required are: (1) good communication links between the field (production areas), the diagnostic and research laboratories, and the central command structures; (2) rapid and accurate diagnostic methods with epidemiologically sound response; and (3) efficacious and safe prophylactic or treatment options that can be deployed under emergency operations or programmed in progressive control campaigns.

The resumption of trade after the occurrence of a disease such as FMD, rinderpest, contagious bovine pleuropneumonia, highly pathogenic avian influenza or bovine spongiform encephalopathy, to name a few important livestock diseases,13 would require a robust veterinary service with the necessary institutional framework to demonstrate all activities carried out in the field, the laboratory and abattoirs on the progressive control, and passive and active surveillance leading to the absence of the condition. These methods should be scientifically based and stand up to internal and external auditing. FAO has on several occasions provided assistance and inputs to strengthen such activities (notably, in the cases of rinderpest in Africa and Asia, bovine spongiform encephalopathy surveillance in South America, and the current avian influenza crisis in Asia). The OIE is the standard-setting body in its guidelines for trade in animals and commodities of animal origin (aquaculture is handled in a parallel manner but separate from terrestrial animals). Yet, trade is a relationship between two consenting countries or partners and independent of OIE guidelines; but as an increasing number of countries become signatories to the World Trade Organization (and are members of the OIE), they should observe OIE guidelines and standards in their trade relationships, thus providing necessary transparency and expediency of action.

Enhancing the capacity of a developing country to meet international sanitary and phytosanitary requirements relies on investment in training in all aspects of administration, governance, regulation and legislation, technology, information and documentation. It should be based on equitable systems providing a level playing field (i.e. subsidies to agriculture in the developed world) and enhanced in a realistic, practical manner that allows the country to have the necessary depth with succession planning in human resources and self-assessed performance indicators. Capacity building is not a single occasion event; inputs are needed more often than is appreciated. Again, the OIE, FAO and numerous private consultancies are able to provide such guidance.

The priority within FAO is sustainable agriculture and rural development. The Global Framework for the Progressive Control of Transboundary Animal Diseases represents the collaboration of the two lead international institutions to curb the crippling effect of selected epidemic animal diseases on livestock production and trade. Under GF-TADs, developed countries would decrease the risk of introduction by reducing incidence in endemically affected areas. Developing countries, where these diseases are most often reported, would benefit from the Global Framework as the effort to strengthen veterinary services, build the necessary institutions and foment public/private partnership, which should lead to development of healthy animal production and allow rural economies to participate better in formal trade, whether local, regional or international.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCE INFORMATION

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are indebted to Samuel Jutzi, Director, Animal Production and Health Division, Joseph Domenech and Yves Cheneau, current and previous Chiefs of the FAO Animal Health Service, and Mark Rweyemamu (Tanzania) and Roger Paskin (Namibia) for their unwavering commitment, fine insight, commentary and development of the EMPRES-Livestock programme.

Rohana P. Subasinghe

Fishery Resources Division

Fisheries Department

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

Viale delle Terme di Caracalla

00100 Rome, Italy

E-mail: [email protected]

Subasinghe, R.P. 2005. Experiences in dealing with aquatic animal disease emergencies in Asia. p. 67–72. In: Subasinghe, R.P.; Arthur, J.R. (eds.). Regional workshop on preparedness and response to aquatic animal health emergencies in Asia. Jakarta, Indonesia, 21–23 September 2004. FAO Fisheries Proceedings. No. 4. Rome, FAO. 2005. 178p.

ABSTRACT

This paper presents a brief introduction to the disease problems facing aquaculture in Asia and some current efforts to deal with epizootics caused by transboundary aquatic animal diseases (TAADs).

INTRODUCTION

Aquaculture is the fastest growing food-producing sector in the world. A great proportion (over 90 percent) of this production comes from the developing world. In contrast to terrestrial farming systems, where the bulk of global production is based on a limited number of animal and plant species, the aquaculture sector comprises of over 230 different species. This large number of species cultivated reflects the diversity of the sector, particularly the wide variety of candidate species cultivated and the different production systems used. According to the latest Food and Agriculture of the United Nations (FAO) statistics, the contribution of aquaculture to global supplies of fish, crustaceans and molluscs continues to grow, increasing from 3.9 percent of total production by weight in 1970 to 29.9 percent in 2002. Aquaculture continues to grow more rapidly than all other animal food-producing sectors. Worldwide, the sector has grown at an average rate of 8.9 percent per year since 1970, compared with only 1.2 percent for capture fisheries and 2.8 percent for terrestrial farmed meat production systems over the same period. Production from aquaculture has greatly outpaced population growth, with per capita supply from aquaculture increasing from 0.7 kg in 1970 to 6.4 kg in 2002, an average annual growth rate of 7.2 percent.

In 2002, total world aquaculture production (including aquatic plants) was reported to be 51.4 million tonnes by volume and US$60.0 billion by value. This represents an annual increase of 6.1 percent in volume and 2.9 percent in value, respectively, over reported figures for 2000. In 2002, countries in Asia accounted for 91.2 percent of the production and 82.0 percent of the value. Of the world total, the People's Republic of China produced 71.2 percent of the total volume and 54.7 percent of the total value of aquaculture production. The majority of aquaculture production of fish, crustaceans and molluscs continues to come from the freshwater environment (57.7 percent by volume and 48.4 percent by value). Mariculture contributes 36.5 percent of production and 35.7 percent of the total value. Although brackishwater production represented only 5.8 percent of production volume in 2002, it contributed 15.9 percent of the total value, reflecting the prominence of high-value crustaceans and finfish.

M.G. BONDAD-REANTASO

Cultured Kappaphycus alvarezii in fixed, off-bottom lines in Batangas, Philippines

M.G. BONDAD-REANTASO

Seaweed farming (aquatic plant) in Batangas Province, Philippines

FISH AS NUTRITIOUS FOOD

Fish is an important part of the diet for a large proportion of the people living in the developing world. Many types and forms of fish and aquatic products are available at affordable prices in developing countries. Economic affordability is a key factor as to why aquaculture is making an essential contribution to human health in the developing world. More “foodfish”is consumed globally on a per capita basis than any other type of meat or animal protein. The main reason for the high demand for staple foodfish within most developing countries is its greater affordability to the poorer segments of the community. At present, foodfish represents the primary source of animal protein (contributing more than 25 percent of the total animal protein supply) for about one billion people within 58 countries worldwide, including many developing countries and low-income food-deficit countries (LIFDCs) (value excludes China).

Fish are important sources for many nutrients, including protein of very high quality, retinol (vitamin A), vitamin D, vitamin E, iodine and selenium. Evidence is increasing that the consumption of fish enhances brain development and learning in children, protects vision and eye health, and offers protection from cardiovascular disease and some cancers. The fats and fatty acids in fish, particularly the long-chain n-3 fatty acids (n-3 PUFA), are highly beneficial and difficult to obtain from other food sources.

M.G. BONDAD-REANTASO

Various species of aquacultured fresh and marine food fish sold in a wet market in Riga, Latvia

DISEASES AND HEALTH AS A CONSTRAINT TO AQUACULTURE PRODUCTION

Although aquaculture is the fastest growing food-production sector in the world, diseases are a primary constraint to the growth of the aquaculture sector in many parts of the world. A multitude of factors has contributed to the health problems currently faced by aquaculture. Over the past three decades, aquaculture has expanded, intensified and diversified, based heavily on movements of live aquatic animals and their products (broodstock, seed and feed). This trend has been triggered by changing circumstances and perspectives, especially the liberalization of world trade. New outlooks and directions have accelerated the accidental spread of diseases into new populations and geographic regions, for example, through movements of hatchery-produced stocks and new species for culture, enhancement and development of the ornamental fish trade.

QING-YIN WANG

Shrimp pond in China

There is now convincing evidence of the serious socio-economic, environmental and international trade consequences arising from transboundary aquatic animal diseases (TAADs). These impacts occur on top of the routine needs of managing the opportunistic disease challenges mentioned in the Introduction. Bearing this in mind, and taking Asia-Pacific as an example of a region highly dependent upon aquaculture production and capture fisheries, we need to look at exactly what these impacts are.

Although translocation of pathogens and diseases with movements of their hosts is by no means a new phenomenon, it has only recently gained focussed attention in many regions. Advances in live aquatic animal trade, facilitated by improved transportation efficiency, are now recognized as having played a pivotal role in the introduction and spread of pathogens and diseases into many aquaculture systems. There is now convincing evidence of the serious socio-economic, environmental and international trade consequences arising from transboundary aquatic animal diseases. For instance, combined losses from shrimp diseases at the global level from 11 countries for the period 1987 to 1994 were estimated at US$3 019 million. More recent examples of major losses due to the spread of aquatic animal diseases include that of carp mortalities (losses estimated at 50 billion Indonesian rupiah, approximately US$5.5 million) in Indonesia; Koi herpes virus (KHV) (losses estimated at 150 million yen, approximately US$1.4 million) in Japan; and abalone mortalities (losses estimated at 400 million TWD, approximately US$11.4 million) in Taiwan, Province of China.

In addition to the obvious effects of large-scale aquaculture losses on rural communities, diseases also cause considerable financial impact on investor confidence. These losses are even more alarming where the success or failure of a harvest will determine the raising of families above or below the United Nations (UN) poverty threshold. In southern Viet Nam, approximately 1 200 families dependent on rice-shrimp culture have experienced annual losses of more than US$300000 due to shrimp diseases. Between 1995 and 1997, the “red spot disease”of grass carp affected 4000 of 5000 cages in operation, with losses estimated at US$0.5 million. Such losses in these situations directly threaten the livelihoods of the communities they occur in through reduced food availability and loss of income and employment, as well as other associated social consequences.

Besides recent outbreaks of Taura syndrome virus (TSV) and KHV, which will be dealt with in detail in other presentations, some other examples of transboundary aquatic animal diseases in the Asia-Pacific and their impacts are briefly discussed below:

Epizootic ulcerative syndrome (EUS)

This serious epizootic, first reported in Japan as mycotic granulomatosis (MG) of freshwater ayu (Plectoglossus altivelis) in 1971 and observed in eastern Australia in 1972, is now reported to occur in most Southeast and South Asian countries, affecting over 100 species of wild and cultured fresh and to a lesser extent brackishwater fish. The primary causative agent of this disease has been confirmed as a fungus of the genus Aphanomyces. Combined losses from EUS in several Asian countries before 1990 were more than US$10 million; losses in Thailand alone from 1983–1993 were US$100 million. EUS continues to expand its range, the latest extension being into the rivers of the Indus in the Punjab of Pakistan. Outbreaks of ulcerative disease in Brevoortia tyrannus in the United States are very similar to EUS in Asia.

M.G. BONDAD-REANTASO

Red spot disease of grass carp in Viet Nam

White spot syndrome virus (WSSV)