By

Marius Botha, the Water Research Commission, South Africa

General context

Background

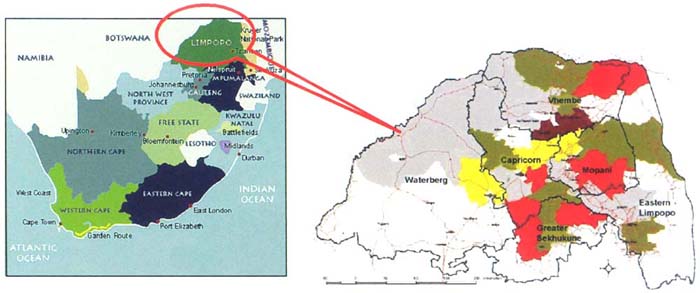

The Limpopo Province is one of the nine provinces of the Republic of South Africa and is situated in the Northeastern corner of the country. A unique feature of this province is that it shares international borders with three countries: Botswana to the west and northwest, Zimbabwe to the north, and Mozambique to the east. Limpopo is the link between South Africa and countries further afield in sub-Saharan Africa. On its Southern flank, the province shares borders with Gauteng, with its Johannesburg-Pretoria axis, the most industrious metropole on the continent. Thus, the province is placed at the centre of the vortex of developing markets, regional, national and international.

The Limpopo Province government has identified agriculture, tourism and mining as the priority areas for developing the province's economy. Following major investment in the past few years in mining and tourism, there is a new focus now on agriculture because of its potential for job creation among the poorest sectors of society, many of whom already have access to agricultural resources. The province has well developed but currently under-utilised smallholder irrigation infrastructure, which could play a central role in the revitalisation of the local economy in the rural areas of the province. Limpopo Province is one of the poorest areas in South Africa and one of the priority nodes earmarked for investment through the South African Government's Integrated Sustainable Rural Development (ISRD) programme. Irrigation potential has been identified in eleven of the first thirteen nodes earmarked countrywide for implementation of the ISRD.

The Water Research Commission of South Africa (WRC) publication: “Developing Sustainable Small-Scale Farmer Irrigation in Poor Rural Communities: Guidelines and Checklists for Trainers and Development Facilitators” (WRC Report No. 774/1/00) is directly relevant to the implementation of the ISRD and the Revitalisation of Smallholder Irrigation Schemes (RESIS) programme in Limpopo Province.

Through a WRC research project, the WRC Guidelines were tested as a means to increase the accessibility of meaningful training and capacity building where small-scale irrigation forms part of integrated sustainable rural development initiatives. This paper attempts to summarize the main aspects of this project, which has been ongoing for the past three and a half years and is now nearing completion.

The research included the development of training material and training of Farmer Trainers. Further, it was tested how training can be provided through the two Agricultural Colleges in the Limpopo Province. The Limpopo Province Department of Agriculture (LDA) now has several years' experience with the revitalization and rehabilitation of smallholder irrigation schemes. The LDA's assessment of the impact of their actions to date has convinced them of the value their training and capacity building activities have had on improving livelihoods. However, farmers requested that the training needs must be broadened from a basic agricultural production focus, also covering business and marketing skills and water management training to improve fair sharing of water amongst users. The LDA was also concerned that they have insufficient capacity to expand from eight pilot schemes to approximately 126 irrigation schemes in Limpopo Province and a large sector of small-scale irrigation production on community and home food gardens currently without access to this type of training and capacity building.

In view of this, LDA requested the International Water Management Institute (IWMI) in South Africa, to develop a proposal for a project to broaden smallholder irrigation farmers' access to this training and capacity building. The training and capacity building have been ongoing in the province for the past few years and is now extended throughout the province within the current expanded programme for Revitalization of Smallholder Irrigation Schemes (RESIS).

Limpopo Programme on Revitalization of Smallholder Irrigation Schemes (RESIS)

The National Guidelines on Agricultural Water Use of South Africa describes government policy to transfer the management of smallholder irrigation schemes to farmers and to broaden opportunities for multiple agricultural water uses to rural communities. The Limpopo Department of Agriculture (LDA) has taken the lead in implementation of this policy by launching a major programme for the Revitalization of Smallholder Irrigation Schemes (RESIS). This is a provincial and national flagship programme to combat poverty and joblessness in the rural areas.

RESIS strives at transformation of society by enabling rural households to exercise much more control over their daily lives and especially their economic activity. This is achieved by giving the farmers authority over management and expenditure on their irrigation scheme infrastructure and farming choices, supported by training, capacity building and mentoring. Simultaneously, the general lack of access to farming inputs and services is addressed, as well as the upgrading and redesign of infrastructure to enable management-by-the-farmers.

Further, RESIS strives to maximize benefits to the broader community by addressing community agricultural water needs, water for homestead gardening, animal watering and dipping tanks, and training and support for dryland crop production.

Each of the 126 irrigation schemes in the RESIS programme requires at least a full four-year period of intervention to complete the RESIS project cycle. All 126 schemes need to be completed within a six-year term. This implies that activities need to run in parallel on all schemes for a couple of years.

The overall goal of the RESIS programme is to raise and sustain incomes of farm families in Limpopo Province on irrigation schemes and in the villages surrounding them within the Programme period from 2004–2010. This goal will be achieved through the following activities:

The Limpopo Farmer Training Team, based at the Agricultural Colleges, are playing a key role in the implementation of the RESIS programme and are using, testing, refining and expanding the Facilitators' Guide.

The Limpopo Farmer Training Team has completed their maiden training on all the maize training modules, except where local circumstances have necessitated postponement, such as a crocodile attack in one village the day before a scheduled training event.

Institutionalization of farmer training in Limpopo Province

Thus, in order to broaden smallholder farmers' access to relevant training, the Limpopo Department of Agriculture (LDA) embarked on this process to build farmer training into the curricula offered by the Agricultural Colleges in the Province. The Water Research Commission (WRC), IWMI South Africa and the Agricultural Research Council of South Africa's Institute for Agricultural Engineering, backed up this initiative with research support through this research project. This process is viewed as a pilot exercise for national expansion, aligning to the development of the SA government's National Strategy for Education and Training for Agriculture and Rural Development. This is an action research - capacity building project, aimed at transferring practical skills to previously disadvantaged individuals, institutions and communities. Resource poor farmers, youth and women's groups are the primary target groups for enhanced skills in agricultural production, water use and management, business and entrepreneurial skills.

The lessons learnt from this action research project could assist in the implementation of similar programmes, particularly in support of initiatives under the Integrated Sustainable Rural Development Programme.

Smallholder farmers currently have limited access to training. Furthermore, formally available training is focused almost exclusively on scaled-down versions of high-cost, high-risk commercial production practices, which are especially inappropriate to food insecure households. Much of the current training also requires trainees to be away from their homes for periods ranging between three weeks and several months. This is impossible for many - especially so for the women responsible for food insecure households. Most of the farmer training in the Limpopo RESIS programme is offered on-farm.

The Agricultural College in the Limpopo Province has taken a basic decision to provide training at the Further Education and Training (FET - Grade 9–12) level, rather than the Higher Education (HE) level (the level at which the Technikons and Universities provide services). Further, the Agricultural College has decided to shift their focus towards the training of smallholder farmers, whereas before they trained extension staff only. One of the challenges associated with offering farmer training is to further develop the Agricultural Colleges' capacity (skills and physical resources) to offer on-farm training.

The “Limpopo Farmer Training Task Team” was established to provide guidance and direction to this joint LDA/WRC initiative.

The Limpopo Farmer Training has proven to be highly successful and effective and forms the basis of two new Qualifications to be developed and institutionalized through proper curricula within the Agricultural Colleges namely: Farmer and Farmer Trainer.

Water Research Commission of South Africa Guidelines

The “Water Research Commission Guidelines on Developing Sustainable Small-scale Farmer Irrigation in Poor Rural Communities” forms the basis of this WRC project, which aims to implement and test these guidelines. The WRC Guidelines and the training offered through the RESIS Programme in Limpopo Province, builds on the work of several training providers. It was critical that not only the training content, but also the approach followed by these training providers, be studied and properly recorded in a scientifically verifiable way.

The approach of “development through needs-based training” was first developed and applied successfully over a period of five years during the late 1980s and early 1990s by a Mr Johann Adendorf in the training of approximately 7 000 poverty-stricken dryland maize farmers in Phokoane, in the Nebo district of the Limpopo Province. Through appropriate training, organisation and improved self-confidence, farmers considerably improved their yields from an average of 3.5 bags per typical 1.2 hectare holding, to a new average of 40 bags. This intervention improved the general standard of living in the Phokoane area from a typical household situation of one meal in three days, to surplus production of 11 000 tonnes from the area. The “development through needs-based training” approach has since been used in several dry land areas in South Africa and is currently being used in poor rural communities with access to irrigation schemes. In particular, the Limpopo RESIS programme provided a valuable opportunity to implement and test Adendorf's training and the WRC Guidelines. What makes this approach and specifically the training material itself so unique can be summarized as follows:

The information and data gathered in this WRC project on Adendorf's and other training providers' training used in the RESIS programme, is being used to develop further training courses and training modules based on the same principles. These curricula are now being institutionalised at the two Agricultural Colleges in the Limpopo Province, Tompi Seleka (near Marble Hall) and Madzivhandila (near Thohoyandou). It is envisioned that, after successful institutionalisation of the curricula at these two colleges, the process could be duplicated at other Agricultural Colleges throughout the country.

South African Qualifications Authority (SAQA) requirements and the National Qualifications Framework (NQF)

This Water Research Commission (WRC) project aimed to support the institutionalization of the training offered through the RESIS programme, into the Limpopo Agricultural Colleges. Therefore, the material has to be recognized by the Agriculture Sector Education and Training Authority (AgriSeta).

Who is “SAQA”?

In order to have the training courses, modules and curricula recognized by and accredited with the South African Qualifications Authority (SAQA), the training content had to be developed in a specific format required by SAQA, called Unit Standards. The South African Qualifications Authority is a body of 29 members appointed by the Ministers of Education and Labour. The members are nominated by identified national stakeholders in education and training.

What is a “National Qualifications Framework”?

It is a framework i.e. it sets the boundaries - a set of principles and guidelines, which provide a vision, a philosophical base and an organizational structure - for construction, in this case, of a qualifications system. Detailed development and implementation is carried out within these boundaries. It is national because it is a national resource, representing a national effort at integrating education and training into a unified structure of recognized qualifications. It is a framework of qualifications i.e. records of learner achievement. In short, the NQF is the set of principles and guidelines by which records of learner achievement are registered to enable national recognition of acquired skills and knowledge, thereby ensuring an integrated system that encourages life-long learning. Unit Standards form the basis for Outcomes Based Education - which focuses on training and education that is aimed at achieving specific practical outcomes or results. Unit Standards are composed of several ‘Specific Outcomes’1, each with several ‘Learning Units/Outcomes'2, for each separate aspect, which has to be covered in the training. These smaller parts, which make up a Standard, are called Credits (See diagram). Each credit is equal to an average of about ten notional hours. People can earn their credits without going to a course if they can show that they already have the skills and knowledge required in the standards and qualifications. This Recognition of Prior Learning (RPL) means that peoples' skills must be recognized even if they have learnt it simply through doing rather than through a formal course or qualification. When Unit Standards are put together, they form Qualifications, which are then registered on the National Qualifications Framework (NQF).

Diagram 1. Potential Farmer Trainers and Career Path

The NQF is like a single but wide ladder which covers all the many possible learning and career paths. The learning paths include all forms of education and training. The”ladder” is designed to make it easy for people to move sideways as well as upwards, for example, when they want to move from one type of learning to another or from one career to another. From these levels within the NQF, it is clear how far a person is from the bottom or top and what the next step is. All types of learning and career paths have the same steps or levels, so that progress can be recognized wherever a person is. The NQF is made up of eight levels of learning and pathways for learning specializations (See Table 1.1). Different qualifications fit into the framework according to their focus and how difficult they are. The level of a qualification is based on the exit level - on what a person will know and be able to do when he/she finishes his/her qualification. This new way of recognising learners' achievements applies to all qualifications, giving education and training the same status. It measures what a person knows and can do, rather than where, what and how the person learnt. The Farmer Training primarily subscribes to the ABET (Adult Basic Education Training) Level on the NQF, while the ‘Train the Trainer’, the Technician and the College Lecturer Training may subscribe to any and all of the levels on the NQF (ABET levels 1–4, NQF levels 1–8, where ABET level 4 and NQF level 1 overlaps).

Table 1. The National Qualifications Framework (NQF)

| NQF Level | BAND | ||||

| 8 | Higher education and training | Post-doctoral research degree Doctorates Masters degrees Professional qualifications Honours degrees Higher diplomas National diplomas National certificates | Universities Technikons Colleges | ||

| 7 | |||||

| 6 | |||||

| 5 | |||||

| FURTHER EDUCATION AND TRAINING CERTIFICATE | |||||

| 4 | FET | School/ College/Trade certificates | Private schools Government schools | Technical community some police, some nursing, private colleges | RDP and labour market schemes, unions, workplaces etc. |

| 3 | |||||

| 2 | |||||

| GENERAL EDUCATION AND TRAINING CERTIFICATE | |||||

| 1 | Std 7/grade 9 (10 years) | ABET level 4 | Formal schools Urban, rural, farm, special schools | Occupation, work-based training, RDP, labour market schemes, upliftment programmes, community programmes | NGOs, churches, night schools, private ABET programmes, unions, workplaces, etc. |

| Std 5/grade 7 (8 years) | ABET level 3 | ||||

| Std 3/grade 5 (6 years) | ABET level 2 | ||||

| Std 1/grade 3 (4 years) | ABET level 1 | ||||

| 1 year reception | |||||

Adult Basic Education Training (ABET) teaching principles

An “OBE Training of Trainers Workshop” was held between 17 and 21 February 2003 and between 30 March and 4 April 2003 at the National Community Water and Sanitation Training Institute (NCWSTI), University of the North, Limpopo Province. The aim of this workshop was to familiarize the WRC/Limpopo Farmer Training Team with the basic principles and requirements for designing Outcomes Based Education training material, based on Adult Basic Education Training principles.

The specific objectives of the workshop were to:

Familiarize participants with the principles and requirements for designing:

Assessment criteria

Using the nominal round technique of assimilating information, the following characteristics of the Adult Learner were identified by the WRC/Limpopo Farmer Trainer Team during the Training of Trainers Workshop.

Adult learners

Learning experience is influenced by:

cultural background

a) How to motivate adult learners

Once the characteristics of Adult Learners had been discussed, a number of factors that may cause resistance to change and learning were noted, namely:

b) Participatory methods and dialogic learning

Participatory training methods ensure that training is learning-centred and not teacher - or learner-centred. Individuals choose methods of learning that are linked to their senses. Some learners predominantly use one sense while others use different senses at different times. A training programme should therefore appeal to the following three main senses:

The trainer should take note of the following issues when using participatory training methods:

Examples of participatory training methods that may be used include:

|

|

An important issue that was raised during this discussion was the attitude of the trainer. The image of a broken bottle was used to describe the target group for training, which is a poverty stricken rural farmer whose self-image has been broken. The ‘glue’ that should be used to mend the broken bottle (= self image), is “LOVE” which is explained as follows:

Capacity development needs assessment study at the system/environmental institution/individual level

Farmer training needs

The wide range of needs to be catered for by existing and potential future training programmes was explained with the aid of the matrix discussed in Chapter 1, Table 1.2. It was noted that potential irrigation farmers, such as are catered for by RESIS, only form a small component (56 000 households on a total of 100 000 hectares) of the total spectrum of farmers requiring training in South Africa. Dryland fields by contrast take up approximately 2 million hectares, on which 1.7 million households rely, while 2.4 million households have homestead yards, covering a total area of about 200 000 hectares. Furthermore, about 12 million hectares are used as grazing land for livestock, by approximately 1 700 000 households. The spectrum of farmers was divided into 3 categories:

The need to define particular training needs for this whole spectrum of farmers and activities was emphasized.

Demographic, education and skills profile of rural dwellers in the Limpopo Province, South Africa

Age distribution of sample group of 518 farmers

In a sample group of 518 farmers studied by the Provincial Representative Officers of the National Strategy for Education and Training for Agriculture and Rural Development, it was found that 47 percent of the farmers were older than 50 years.

| Range (age) | Number of people | % |

| 20–25 | 30 | 6.12 |

| 26–30 | 41 | 8.16 |

| 31–35 | 28 | 4.08 |

| 36–40 | 45 | 8.16 |

| 41–45 | 51 | 10.20 |

| 46–50 | 73 | 14.29 |

| 51–55 | 57 | 10.20 |

| 56–60 | 62 | 12.24 |

| 61 and older | 131 | 25.28 |

| Total | 518 | 100.00 |

Gender distribution of sample group of 518 farmers

Of the 518 participants, the majority (53 percent) were female. It was indicated that this percentage will be even higher for all persons active in the agricultural sector and could be between 60 percent and 70 percent. This follows the normal pattern in South Africa with the majority of persons involved in rural agriculture being female. As a rule women are mostly involved with community gardens, dry land and poultry production (which allows them to attend to other responsibilities such as the care of children, preparation of food and general maintenance of the household). Men, on the other hand, are mostly involved with larger projects such as large-scale animal husbandry and irrigation schemes.

Literacy level of sample group of 518 farmers

The participating group was quite diverse in terms of their level of schooling. Sixteen percent of a sample group of 518 farmers have received no schooling at all. The latter group will thus require specific inputs of an ABET nature before enrolment for higher levels of learning. It further implies that learning for this group should preferably be of a practical nature. Written theoretical material should be kept to an absolute minimum.

| 1. | No formal schooling | = 16% | 82% = below Further Education and Training (FET) level. |

| 1. | Grade 0 – Grade 5 | = 46% | |

| 2. | Grade 6 – Grade 10 | = 20% | |

| 3. | Grade 11 – Grade 12 | = 15% | |

| 4. | Tertiary level | = 3% |

Agricultural training needs of rural dwellers in the Limpopo Province

To identify appropriate training needs, it is necessary to understand how those farmers' objectives, and hence their generic training needs, differ between the food insecure household, subsistence and emerging farmers, and commercial, profitable small-scale farmers. The changing objectives and corresponding learning outcomes are summarized as:

Changing objectives of learners along the development path:

| Position on growth path | Learner Objective | Learning Outcome |

| A – Food-insecure household | Food security | Food security through own production |

| B – Subsistence - & emerging farmer | Income generation and self-development | Profitable small-scale farmer |

| C – Profitable commercial small-scale farmer | Improved profit | Efficient and knowledgeable commercial farmer |

| Simplified management and economic growth |

A training needs assessment was also conducted to pinpoint the training needs of smallholder farmers with the aim of developing and providing training relevant to the identified needs of the farmers. Using a systematic approach of needs assessment ensures that gaps in “performance” or competence are identified correctly, which can then be improved through correct training (Gupta, 1999).

The training needs assessment was linked with other surveys conducted in the Limpopo Province namely:

This training needs assessment was aimed at verifying the identified training needs from these reports as well as identifying other training needs not identified in these studies.

Procedures

Meetings were held with irrigation scheme farmers and homestead/dryland farmers at both Mphaila and Kutama communities. The field workers divided themselves into three groups and conducted focus group discussions with eight farmers per group - each group had to be representative of both men and women and a combination of irrigation, homestead and dryland farmers. The idea was to encourage these farmers to share their different farming experiences and needs with each other as well as with the team. Qualitative and quantitative data, per category of farmer, namely, food insecure households, dryland farmers and irrigation farmers, were recorded during these group sessions. At the end of the assessment, the team gathered, presented and discussed their findings in order to generate the needs assessment report.

Findings

The following have been identified as the main irrigation farming activities taking place in the two areas:

From the data collected, it can also be concluded that farming in these areas is constrained by several common problems. These problems are:

Results

The majority of these needs were identified during the needs assessment conducted in Kutama area (Capesthorn Irrigation Scheme) and at Mphaila (Mphaila and Luvhada Irrigation Schemes). However, many other needs were also identified.

The pre-development survey reports do not identify specific training needs. However, from the problems faced by the community under the heading “Agricultural Issues”, training needs can be extracted. These include training on issues such as:

The training needs assessment conducted by the WRC Research Team has identified all these areas for training.

Categorization of identified training needs

| Homestead yards | Dryland fields | Irrigated fields |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Development of farmer training material in the Limpopo Province

Members of the Limpopo Farmer Training Team are now capacitated to develop new Outcomes Based Training material from existing or newly developed training material as well as identify gaps in existing Unit Standards and propose new Unit Standards to be developed by the relevant Standards Generating Bodies for future training requirements. This means that in-house capacity was created in the Limpopo Department of Agriculture to populate the Smallholder Agricultural Training Needs Matrix developed during this WRC research project (see Table below).

This table gives a useful perspective on the range of farmer training needs for which training material needs to be developed. In practice, each training programme should be preceded by a thorough training needs assessment to confirm and prioritize the specific needs of that target group. The ‘pre-development survey’ at the start of each new project in the RESIS Programme serves this purpose.

Table: Spectrum of smallholder agriculture - categories of training needs

| |||||

| Homestead yards | Grazing/ livestock watering | Dry land fields | Irrigated fields | ||

| Number of households (hh) informer homelands with current access to agricultural resources | 2 400 000 hh (100%) | 1 700 000 hh (70%) | 1 700 000 hh (70%) | 56 000hh (2.5%) | |

| Total hectares currently under control of these households | 200 000 ha | 12 000 000 ha | 2 000 000 ha | 100 000 ha | |

| C | Define training needs | Define training needs | Define training needs | Define training needs |

| B | Define training needs | Define training needs | Define training needs | Define training needs | |

| A | Define training needs | Define training needs | Define training needs | Define training needs | |

The existing training material on Development Principles, Scheme Management, Water Management, Maize Production and Cotton Production, was incorporated into the Facilitators' Guide on Farmer Training. Further Outcomes Based training modules, being developed by the Limpopo Farmer Training Team, will over time also be incorporated into the Facilitator's Guide, which is one of the main products/outcomes of this WRC research project.

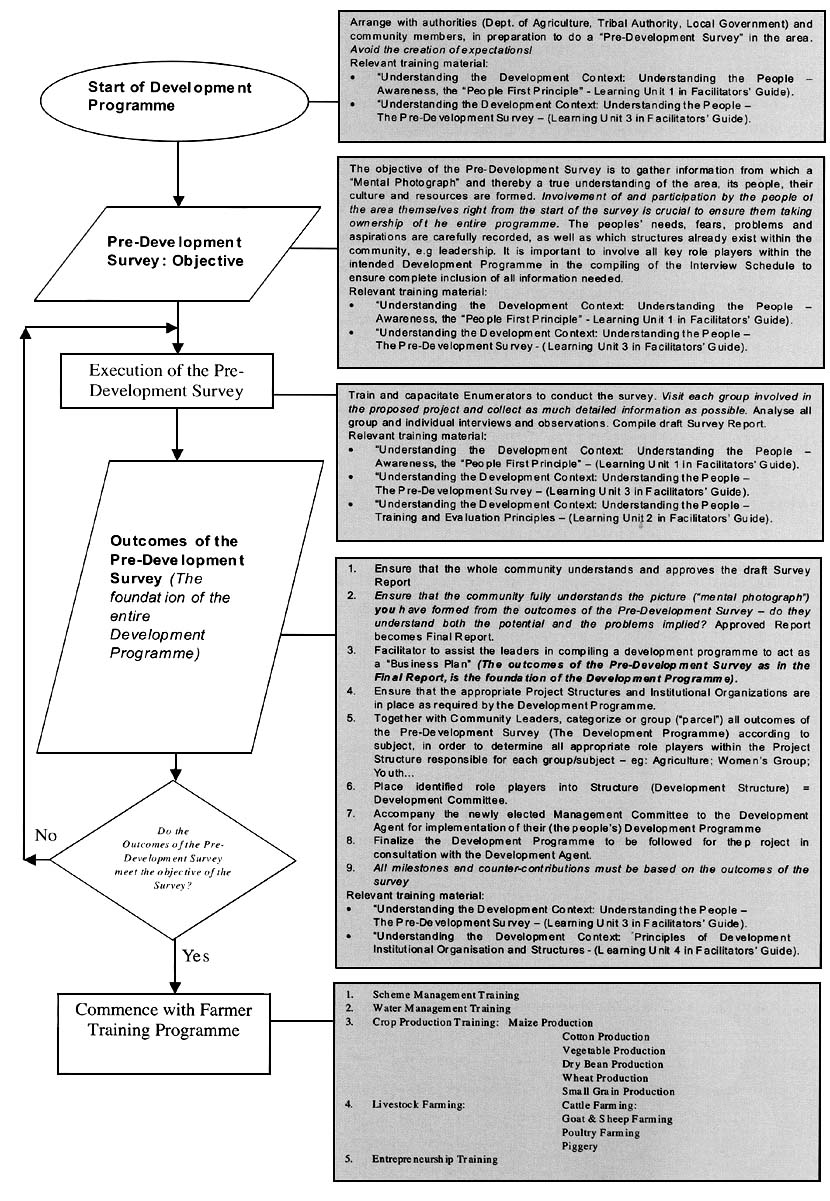

The “Pre-Development Survey”

One of the unique features of this training approach, which is believed to contribute greatly to the success thereof, is the concept of the “Pre-Development Survey”. This is a participatory ‘needs analysis’ with a difference: trainers/training facilitators/development agent representatives spend time in a community or village where development intervention is anticipated, to form a clear ‘mental photograph' of the community, understanding their needs, fears, aspirations, problems, dreams and challenges. This ‘survey' is not only focussed on the agricultural development issues in a community, but actually primarily focus on the ‘softer issues'- the human development aspects. The aim of this training approach is to build people's self-confidence and try to restore their human self-worth, by means of agricultural development.

To best describe the Pre-Development Survey as well as give an insight into the Facilitators' Guide which emanated from this project, the module or ‘learning unit’ on this subject is included here, as it appears in the Facilitators' Guide:

Synthesis of steps taken for the Capacity Development Strategy/Programme Design and Implementation

The first step, which has now been taken for the Development Principles, Scheme Management, Water Management, Maize Production and Cotton Production training modules, was to identify the “gaps” in the existing unit standards and determine the new unit standards that needed to be developed for ABET Level 1. The second step was to develop learning units that are needs-based - the “needs” being those of the actual learners, in this case the farmers. This highlights the importance of the participatory needs analysis, which formed part of the initial stages of this project.

All of the above-mentioned serve as the building blocks for a complete qualification, to be recognized by and registered with SAQA. From this qualification different unit standards and combinations thereof can then be used to form the modules of learning material on the different levels of the NQF.

Step 1: Unit standard gap analysis

AgriSeta supplied the project team with copies of all the existing registered Unit Standards within the AgriSeta. However, although these Unit Standards are quite extensive in terms of quantity, they lack in terms of relevance regarding the aims of this project as they only cover Unit Standards for NQF Level 1. From this information, gaps could be identified of unit standards that were needed on ABET-level 1, but not developed yet.

Step 2: Development of new Unit Standards

The development of Unit Standards involves a process of designing the following components:

An Outcomes Based Education Development Team (WRC-OBE Development Team, now called the “Limpopo Farmer Training Team”) was formed to develop the Specific Outcomes and Assessment Criteria on which the Unit Standards would be based. This team was comprised of a wide representation of people including representatives of the Limpopo Province's two Agricultural Colleges, Madzivhandila and Tompi Seleka, Extension Officers of various districts in the Province and leading Smallholder Farmers.

Step 3: Development of the Facilitators Guide (Training Material)

In addition to developing Specific Outcomes and Assessment Criteria, the Limpopo Farmer Training Team compiled a Facilitators' Guide, which is being used as training manual for trainers of emerging farmers, in the Limpopo Province. The Facilitators Guide forms the main product of this research project.

Step 4: Training of Farmer Trainers whilst training Farmers

After developing the Unit Standards, the Limpopo Farmer Training Team presented the training to farmers in Limpopo over a six-month period, under the guidance and supervision of the training providers who developed the training material. Thus, a methodology for training-of-farmer-trainers was developed and tested. This team of farmer trainers are now known as the Limpopo Farmer Training Team and are fully deployed to offer the training in the expanded RESIS programme.

Suggested Sequence of Training Interventions in the Field

The following ‘flow chart’, as included in the Facilitators' Guide, shows the suggested sequence of applying the different training interventions and learning units or modules in the Guide, as tested in the field over the past three years. This is merely a guide for trainers of a sequence which usually works well - each trainer must decide according to the needs of the specific target group, how to best sequence training. Each target group is unique and has unique needs, which the trainer must be attuned and sensitive to at all times:

Problems and difficulties encountered while implementing and successful experiences

Evaluation of training conducted within the RESIS Programme

The Limpopo Farmer Training Team conducted a field visit on 4–5 February 2004 at Beaconsfield, Capesthorn and Homu. On the first two schemes, farmers were trained in 2001 and 2002 as part of the RESIS Programme implementation. On the third scheme, Homu, farmers were currently receiving training as part of the ‘on-the-job’ training of Farmer Trainers in the Limpopo Farmer Training Team. The following were the findings obtained from farmers in the respective schemes.

a) Successful Experiences:

CAPESTHORN (Training: 2000/2001)

The plot sizes are 1.6 hectares. Most of the farmers are women with few men rendering help when necessary. The Limpopo Department of Agriculture conducted farmer training at this scheme in 2000 as part of RESIS Programme. However, before farmers could implement the new knowledge, their dam was washed away during the 2000 floods. It is remarkable that they retained the knowledge until 2003, when their infrastructure was sufficiently repaired to enable planting. The majority of farmers are now implementing what they have learned, with little variations due to availability of resources.

Farmer Ramovha Dabudi has been farming for more than 10 years. Her yields have increased since the training and she is storing surplus maize at the local Cooperative.

Farmer Ana Mufumadi used to harvest 3–4 bags per bed, but this increased to 15–20 bags per bed after training, not counting what is sold as green maize before harvest. She also stores surplus at the Cooperative with a portion converted into maize meal as and when her family needs it.

Training Sequence Flow-Chart: (Suggested)

Farmer Maphari Muthasedi has been farming for the past 25–30 years; after training her yield improved from five bags to 15–20 bags, which according to her is impressive. Bags are stored at Cooperative for maize meal.

Farmer Mrs Netshurumbew has been farming for more than 10 years. The estimated yield before training used to be 5–10 bags. Although she has not yet harvested for grain, she has already sold green cobs and her projected grain yield is 20–25 bags.

BEACONSFIELD (Training: 2001/2002)

Farmers are allocated plots of 1.286 hectares divided into beds of 0.107 hectares. Farmers are mainly women with more than 20 years experience in farming.

Tshinakaho Havhi is approximately 65 years old and used to get 5–7 bags per bed before training. Through the training, conducted in Beaconsfield in 2001/02, she could improve her yield to 10–15 bags per bed. The farmer pointed out that at some stage she managed to sell green maize from just one bed for R800. She indicated that her secret lies in measuring the fertilizer application accurately using the cap of a 2-liter cold drink bottle, exactly according to the training. Furthermore, she keeps her plot weed free at all times. The farmer did at some stage plant groundnuts, which was bought by the local people directly from the fields. The farmer said with confidence that she can compete with men working in the firms, that out of the money earned she successfully paid tuition fee for the two sons of whom one went to the University of Venda, and now both are employed.

Farmer Madzhe Tshnakaho is approximately 65 years old with an experience of 20 years in farming. She practised skills acquired from the training, which improved her yield from three bags to 10–12 bags per bed, not counting the portion sold from the field as green mealies. She has implemented all the practices learned through the training.

HOMU (training by WRC-team in 2003/2004)

Homu irrigation scheme is one of the schemes where the new Farmer Trainers started presenting training from October 2003. At the time of this evaluation, only three of the modules had been presented, but the output of training conducted was amazing. The Limpopo Farmer Training Team visited the plot of Paul Nhlakathe, the chairperson of the scheme, to observe production practices as learned from the training offered. Subsequent follow-up confirmed that the farmer was able to sell the bulk of 60 000 cobs per hectare as green maize at R1.00 per cob.

b) Problems and Difficulties encountered during Implementation

(Note: See also points discussed under “Conclusions” section of this paper)

The Lack of Practical Experience of Trainers -

The lack of practical experience is proving to be a serious problem for many of our trainers. (It must be noted that they are not to be blamed for this shortcoming, they simply have not had the opportunity). However, this is especially visible in their preparation, as they find it exceptionally difficult to identify the real key issues in the chapter, which they have to present. It is also very evident in their presentations and practical demonstrations, and when farmers have asked trainers questions related to the practical side of the lecture and trainers have been unable to give a satisfactory answer due to the lack of experience.

1. It has become very clear that Trainers should be empowered and equipped with all the different aspects required for this level of training, e.g. Training Principles, Theory, Practical Understanding and the Transfer of Technology, before going to the field to do the training. Trainers must be properly qualified, as the old and illiterate farmers who attend the training should never be underestimated.

2. Trainers need to transfer or convey the information in the Facilitators Guide correctly by keeping to the original specifications, e.g. four fingers deep, three rulers apart, etc. Changing of standards or specifications could cause serious problems to colleagues who come after you and are not aware of the changes you have made - it can also confuse the farmers. (We had a good example of a case where the trainer said that farmers could plant maize in rows, three human feet apart. This was very accurate when a male farmer demonstrated this, however when a lady followed this example it was found that her feet were much smaller than that of the male farmer and the measurements given were now completely incorrect).

Conclusions

Way Forward on developing Farmer Trainers

The Limpopo Farmer Training Team is being expanded:

More lecturers from the colleges, extension staff and crop scientists from three Districts have participated in two one-week orientation courses in August and September 2004.

The irrigation scheme farmers in the two areas have shown satisfactory zest for the success of their scheme and farming activities. They perceive their farming as the source of food and income for their households. It is for this reason that irrespective of some constraining problems such as water shortage and lack of knowledge, they remain actively involved in farming. It is therefore safe to believe that with the correct infrastructure, services and training, the irrigation scheme farmers' performance could be improved, thereby increasing their output.

The situation with the homestead and dryland farmers is a different scenario as compared to the irrigation farmers. Although the homestead and dryland farmers have shown an interest in improving their farming activities, they appear highly concerned about the lack of infrastructure, such as fencing. It appears that these kinds of problems result in farmers skipping seasons for planting. It can therefore be concluded that efforts to address infrastructure shortfalls should be considered a significant factor and should be addressed.

This study has verified findings in the ‘Provincial Report on Education and Training for Agriculture and Rural Development in Limpopo Province’ and the Pre-development Surveys conducted in various villages since 2002. It appears that the lack of capacity of farmers is as serious a factor as unavailability of infrastructure, finances and accessible markets in creating an environment conducive for effective farming. It is important to note that farmers at community level are mainly illiterate as indicated in the above-mentioned report. This requires basic training programmes at appropriate levels to be developed and offered. Developing the required training programmes should also take into consideration whether the planned training is meant for initiating a career path or only equipping farmers with basic skills to manage their own farming activities. This would be influenced by several factors such as levels of literacy and training according to SAQA standards.

The two agricultural colleges are on track with the new developments of the training and education system in South Africa. Where they are lacking i.e. OBE methods of training, participatory methods and correct use of equipment, they have expressed wishes to address such issues. Further capacitating these colleges in areas that have been declared wanting will strengthen these entities and ensure that they can best implement future community training projects independently.

The role of the Outreach units at both colleges should grow rapidly in response to the new college mandate of practical, accessible training and support for smallholder farmers.

Evaluation of Farmer Training conducted by College Lecturers and Extension Officers

The Limpopo Farmer Training Team which was developed through this WRC project has grown into a highly motivated, closely knit unit across cultural and discipline barriers which is proud of its ability to support and guide each other and successfully welcome newcomers into their fold.

They see their role as Farmer Trainers as central to the development process, as it enables farmers to dramatically and sustainably increase their farming output and consequently the farmers' personal confidence.

Similarly, the new Farmer Trainers have experienced rapid growth in their own skills, but more significantly, the experience has given members of the Limpopo Farmer Training Team a new sense of purpose and has boosted their self-confidence.

One member describes himself as formerly being a ‘discouraged Extension Officer’ who found it hard to get out of bed in the morning and spent his days whiling away his time with idle talk. Over the past two years, this changed completely, since he now cannot find enough hours in the day to finish what he wants to achieve. Farmers' yields have improved dramatically through his training and he is now highly respected by the communities where he is working.

Another member used to believe she was too old to still achieve something in life. Through participation in the Limpopo Farmer Training Team, she has developed a new purpose in life, transmitting this energy to others. She says: ‘I used to have knowledge and skills, but no confidence. Now I am confident, therefore I can successfully transfer the knowledge I have.’

Another member describes how he was always of the opinion that ‘training’ means ‘offloading information', but as college trainer he used to have nothing to do with how people used the information afterwards. Seeing farmers literally reaping the success of his training in such a short space of time have been a revelation, therefore he wants to devote his full energy to this. As he said in wonder when he saw the rich green maize harvest in the field: ‘This is real!'