Prospects for nutritional security are not only influenced by the factors giving rise to the socio-economic problems reflected in the health and nutrition indicators, they are simultaneously limited and changing in response to a nutritional transition underway in many Asian countries. Asian countries initiated their developmental journeys towards nutrition security over 5 decades ago, with an acquired burden of under-development. While achievements are reflected in increased life expectancy, reductions in infant mortality and wider coverage through immunization and improvement in food security, many formidable challenges remain. Severe forms of nutritional disorders are less common today (Gopalan 1992), but undernutrition and micronutrient deficiencies prevail, though in varying proportions and degrees.

Meanwhile, non-communicable diseases (NCDs), once thought to be prevalent mostly in the developed world are emerging as leading causes of death, illness and disability in many developing Asian countries. Dramatic increases in life expectancy accompanied by profound changes in life style are responsible for the heightened increase in the incidence of these non-communicable diseases (WHO 1997). It is increasingly apparent that undernutrition and later overnutrition are particularly dangerous problems confronting Asian countries, and that this emerging epidemic will transform both health and nutrition needs in the years ahead. Prospects for nutritional security beyond 2000 simultaneously limited and changing in response to this nutritional transition are underway in many Asian countries.

A striking feature of the nutrition transition in developing Asian countries is the rapid increase in the share of the total population living in urban areas. The urban population now represents 35 per cent of the Asian region's total population, but it is growing at about twice the growth rate of overall population (1.5 per cent/year). Coinciding with rural to urban migration, there has been an emergence of urban agriculture and home gardens in urban areas of many Asian countries. Even so, the major impact of urbanisation on the nature of the food supply arises from food being no longer available as home grown produce, nor is food as readily available in urban centres.

The cash economy has assumed far greater significance in supplying food, and these rapidly expanding urban communities place increased demands on food production as well as on transport and storage systems for food distribution and preservation (WHO 1990). The evolution of these urban distribution systems facilitate greater food variety without seasonal or year to year variation and this raises prospects for improved food selection and promotion of greater variety based on nutritional principles. Urbanization profoundly affects dietary and food demand patterns. It also gives rise to growing concern about the quality and safety of food, particularly foods processed and purchased outside the home, and to modification in food preferences caused by changing life styles.

Urbanization contributes to changes in the type of demand for food, and the consumption of food outside the household is rising rapidly. In most Asian metropolitan cities, like Delhi, Bombay, Bangkok, Jakarta and Yangon, a wide range of foods including varieties of breakfasts, main meals and snacks are catered to the needs of urban dwellers, both rich and poor. Such foods sold in the urban slums are based on traditional food items, and are generally freshly prepared and served hot.

A distinct response to this adaptive response to urban life, therefore, is the rapid proliferation of wayside or improvised eating facilities. In Indonesia and the Philippines, urban households spend over 25 per cent of their food budget on street foods, and 90 per cent of Bangkokians regularly purchase food from outside sources.

Simultaneously, there are changes in dietary practices among the groups of urban elites, involving increased preference for fast food items, such as hamburgers and pizza. Similarly among the urban middle class and poor in South Asian countries, fried food items like ‘fritters’, rice based pancakes and the like are preferred. At the same time, rural to urban migration leads to food shifts and more diversified diets.

The nutritional transition underway in Asian countries during the last decade is illustrated by the food shifts shown in Table 18 below. These involve shifts from basic staples, such as millets towards other cereals such as rice and wheat that require less preparation, and, simultaneously, towards consumption of milk and livestock products, fruits and vegetables, and processed foods.

| Dietary Energy Supply (DES) kcal/person/day | ||

| 1980–1982 | 1990–1992 | |

| Indonesia | ||

| Food, total | 2510 | 2696 |

| Vegetable products | 2438 | 2590 |

| Animal products | 72 | 106 |

| Cereals | 1675 | 1775 |

| Starchy roots | 189 | 157 |

| Non cereal/non root vegetable products | 574 | 658 |

| Malaysia | ||

| Food, total | 2697 | 2817 |

| Vegetable products | 2296 | 2358 |

| Animal products | 401 | 458 |

| Cereals | 1308 | 1174 |

| Starchy roots | 70 | 75 |

| Non cereal/non root vegetable products | 918 | 1110 |

| Philippines | ||

| Food, total | 2219 | 2292 |

| Vegetable products | 1972 | 2020 |

| Animal products | 247 | 272 |

| Cereals | 1203 | 1270 |

| Starchy roots | 137 | 98 |

| Non cereal/non root vegetable products | 632 | 652 |

| Thailand | ||

| Food, total | 2218 | 2374 |

| Vegetable products | 2016 | 2134 |

| Animal products | 202 | 240 |

| Cereals | 1450 | 1381 |

| Starchy roots | 40 | 24 |

| Non cereal/non root vegetable products | 526 | 728 |

| Vietnam | ||

| Food, total | 2117 | 2203 |

| Vegetable products | 1990 | 2026 |

| Animal products | 127 | 177 |

| Cereals | 1534 | 1602 |

| Starchy roots | 247 | 157 |

| Non cereal/non root vegetable products | 209 | 268 |

Source: FAO, 1999.

Traditional Asian diets are cereal based, but as societies move up the socio-economic scale, changes take place in both dietary structures and patterns (Gopalan 1992). In all the countries shown, energy intake has progressively increased during the last decade, and there is a trend towards greater consumption of animal sources as compared to vegetable sources in the diet. There is concern over increased consumption of animal products, such as meat from livestock, which not only requires twice as much water for production than plant foods, but livestock production encourages deforestation and further reduces the total food supply (DES) available for direct human consumption. This trend toward urbanisation coincides with rising concerns about water scarcity and the probable diversion of water from agriculture to other sectors. It is predicted by many that increasing water scarcity might result in higher prices for basic food items, especially irrigated food items, with more severe impact on the poorer segments of the population.

Diets are shifting from vegetables such as cereals to non-cereal food sources, and within food grains there are shifts from starchy roots and tubers to polished rice and refined wheat. The most undesirable features of this nutritional transition include the substitution of millet (coarse grains) by more prestigious and more refined cereals, especially wheat and rice, with a progressively trend towards preference for the highly polished varieties of rice. As this trend usually coincides with reductions in the total intake of cereals, the net effect is a major decrease in the fiber content of Asian diets of more than 50 per cent. Another undesirable feature involves the continued low intake of green leafy vegetables (GLV), which come to be scorned as ‘poor man's food’.

Coinciding with urbanization and changing diets, there is increasing awareness about food contamination leading to the evolution of concern about consumer protection and the nutritional impact of environmental pollutants and industrial toxicants. Particularly in urban areas, there is increased concern about food safety from foods produced outside the home, especially street foods. Salmonellosis and related food contamination pose threats to future prospects of inexpensive sources of street foods. Even though they are widely relished, they are sometimes be unsafe and harmful.

Food contamination poses serious threats to wholesome food in the context of modern development, especially contamination introduced by pesticides, industrial pollution, and pollutants from untreated sewage that is discharged into fields and rivers. Of special concern is the interaction of nutritional status with exposure to environmental pollutants and industrial toxicants. Another major concern is intergenerational consequences of exposure by pregnant and lactating women, and the extent to which toxicants affect the fetus or contaminate breast milk.

There is growing concern in Asian countries about the nutritional aspects of the rising incidence for degenerative diseases. Precise data are not yet available for changing trends in degenerative diseases, but small scale data from selected countries illustrate the transition underway throughout the region. Increasing prevalence of certain kinds of cancer in many Asian countries is related to over consumption of fat and possibly to food trends in degenerative diseases, but small scale data from selected countries illustrate the transition underway throughout the region. Increasing prevalence of certain kinds of cancer in many Asian countries is related to over consumption of fat and possibly to food contamination, especially toxic substances from uncontrolled environmental hazards and industrial pollutants, and possibly due to increased use of pesticides and improper use of modern agricultural technology. Kachondham et. al (1991) reports cancer now ranks as the third leading cause of death in Thailand. However, this at present remains at best an epidemiological link and efforts should be made to address the causes.

Incidence rates of cancer in all sites in India are generally lower than in Thailand, but cancers of upperaerodigestive tracts are much higher than those reported in other countries of the world (Notani 1990). The victims of oral and oesophageal cancers in India are most prevalent among low socio-economic groups, where dietary deficiencies rather than excesses predominate. Research highlights the relationship to oral and oesophageal cancers of lower intakes of carotene and riboflavin in the diet as well as low levels of serum albumin, vitamin A, E, folate and zinc.

Obesity as a nutritional concern and problem has increased dramatically in many Asian countries. This is of profound significance, because of the clearly defined ill effects of obesity, especially when centrally distributed, in relation to diabetes, coronary heart disease and other chronic diseases of life style. Genetic and environmental factors play an important role in determining the propensity of obesity in populations and individuals. Lack of physical activity reportedly contributes to the increasing rates of obesity observed in many countries and may be a factor in whether an individual who is at risk will become overweight or obese. Excess energy in any form will promote body fat accumulation and will lead to obesity if energy expenditure is not increased.

The Nutrition Division in Thailand reports that the prevalence of diabetes has nearly doubled during the last 2 decades and current figures may be even higher. The incidence of diabetes is also on the rise in India, especially among the affluent population aged 40 to 50 years. A Singaporean investigation covering Indians, Malays and Chinese (Thai et. al 1987) shows major increases in diabetes prevalence during the last 15 years.

There is increasing concern about diseases of the heart, as illustrated by research findings showing the prevalence of hypertension as high as 17 per cent in Bangkok and in other regions of Thailand. Studies from Malaysia show the simultaneous emergence of obesity, hypertension and hypercholesterolemia as public health problems, of special concern in rural communities.

Coronary heart disease (CHD) has become a major public health problem in India, where it is most prevalent among both males and females with higher socio-economic status. Studies at the National Institute of Nutrition (NIN) in India show rising incidence of obesity among the affluent and a rising potential for obesity due to reduced physical activity associated with economic activity, in urban as compared to rural areas. Studies among adult Indian women find increased incidence of obesity during the last decade (NIN 1993, NNMB 1996).

With increasing affluence in Singapore over the last 3 decades, disease patterns have undergone a great change, giving rise to simultaneous and dramatic increases in ‘diseases of affluence’ (e.g. certain cancers, heart disease, stroke and diabetes) that are attributed to changing food consumption patterns.

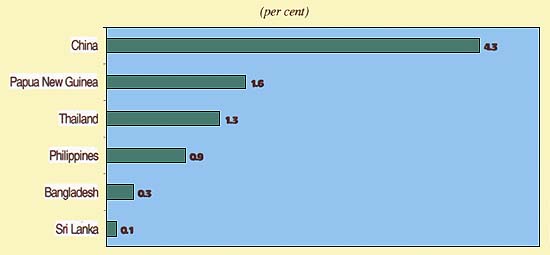

On the whole, the nutrition transition throughout Asia is increasingly associated with a shift in the structure of the diet, reduced physical activity and rapid increases in the prevalence of obesity (Popkin 1994). In response to growing concern about obesity, nutrition indicators are beginning to be collected to determine the prevalence of obesity. Surveys conducted in some Asian countries, featured in Figure 9 below, highlight this concern for obesity among children under age 5 years.

Figure 9. Obesity Prevalence among Children under Age 5 Years

Source: The Sixth World Survey (Rome: FAO) 1996.

Studies among school-age children highlight the trend towards childhood obesity that is initiated among children under age 5 years. In Jakarta, the prevalence is suggested to be as high as 31 per cent among boys and 7 per cent among girls. Recent reports in Thailand show obesity ranging from 9 to 19 per cent among school-aged children, and from 20 to 30 per cent among urban adults. An increased incidence of obesity also is observed among adolescent youth in Asian countries, where it coincides with selective undernutrition and the rising prevalence of anorexia nervosa among girls and boys.

Studies show that even modest advances in prosperity in low GNP developing countries are associated with marked increases in degenerative diseases. The transition leads to increased consumption of fat and rising intake of animal protein, especially among affluent households where result is often obesity.

The incidence of osteoporotic hip fracture (HP) increased two to three times during the last decade in Hong Kong, Singapore and Japan. Though the current incidence of HP in the Asian population remains lower than the Caucasians, by the year 2050 it is estimated that about 3.2 million people in Asia will suffer from HP. Joint diseases like osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis are reported for older women in India. Women are especially vulnerable, e.g. 89 per cent of older women in Thailand consume less than two-thirds of recommended daily requirements of calcium, which puts them at risk to osteoporosis. Calcium intake needs to be increased both from readily available bony fish as well as milk.

These risk factors need to be studied from an Asian perspective, with due regard to the roles of genetic-heredity, nutrients and exercise on achieving peak bone mass and in the prevention of osteoporosis. Data on the bio-availability of calcium from non-milk foods to help Asians meet their calcium intake is also necessary, in view of the urbanization and sedentary lifestyles sweeping over most of Asia, especially among the new affluent groups. Adoption of a prudent diet with adequate calcium intake and increases in physical activity may serve as preventive measures against the development of osteoporosis. These concerns are likely to increase in response to population ageing of Asian countries.

This nutritional transition throughout Asian countries coincides with a global process of population ageing, and their linkage has yet to be fully understood and adequately reflected in a responsive policy framework. Between 1950 and 2025, the total world population will experience a three-fold increase, and the number of older persons, aged 60 and over, will increase six fold. As the older share of the population increases from five to nearly ten per cent, the child share (under age 5 years) of the world total will shrink to less than ten per cent. This new older share will exceed the child share of the total world population for the first time in human history.

The projections for population ageing, shown in Table 19 below, highlight the magnitude of this global process in Asia. Most developing countries are ill-prepared for population ageing, especially as regard to the associated health and nutritional problems, such as increased prevalence of both under- and over- nutrition among older persons, as well as osteoporosis. The design and implementation of effective strategies and measures responding to the combination of nutritional concerns among older people, the majority of whom are women, are important determinants of Asian prospects beyond 2000.

| Country | 1980 | 2000 | 2050 |

| Bangladesh | 3 792(4.3) | 6 504(4.3) | 16 819(7.5) |

| Bhutan | 65 (5.02) | 110(5.42) | 238(7.52) |

| DPR Korea | 1 028(5.02) | 1912(7.02) | 4 715(12.55) |

| India | 33 936(4.96) | 65 655(6.83) | 146 224 (11.85) |

| Indonesia | 8 012 (5.03) | 14 908 (7.50) | 31 287 (12.67) |

| Mongolia | 84 (5.03) | 174 (6.48) | 409(10.37) |

| Myanmar | 2155(6.11) | 3671(6.66) | 7447(9.13) |

| Nepal | 719(5.03) | 1276(5.67) | 2544(7.57) |

| Sri Lanka | 943(6.37) | 1800(8.54) | 4084(15.21) |

| Thailand | 2330(4.95) | 4496(6.55) | 12 179 (13.52) |

Source: WHO/SEARO, 1990